1. Introduction

Generative AI (GenAI) represents the forefront of AI development and is profoundly reshaping the workforce by automating complex cognitive tasks, changing traditional workflows, and assisting with nearly all job functions (

Eloundou et al., 2024). For example, GenAI accelerates the iterative design processes for creators (

B. C. Lee & Chung, 2024), supports consultants in addressing realistic consulting tasks (

Dell’Acqua et al., 2023), assists with software development tasks (

Peng et al., 2023), and serves as a virtual customer service agent to support staff in resolving client issues (

Brynjolfsson & Raymond, 2023). These technological changes require employees to continuously update their skills, redefine their job responsibilities to collaborate effectively with GenAI, and even re-evaluate their professional and organizational identities. In response, employees may proactively modify the boundaries of their job, which marks the beginning of job crafting behaviors (

Wrzesniewski & Dutton, 2001). Job crafting is often categorized into two orientations: approach and avoidance (

F. Zhang & Parker, 2019). Since these two forms lead to distinct work-related outcomes such as job engagement (

J. Y. Lee & Lee, 2018) and job performance (

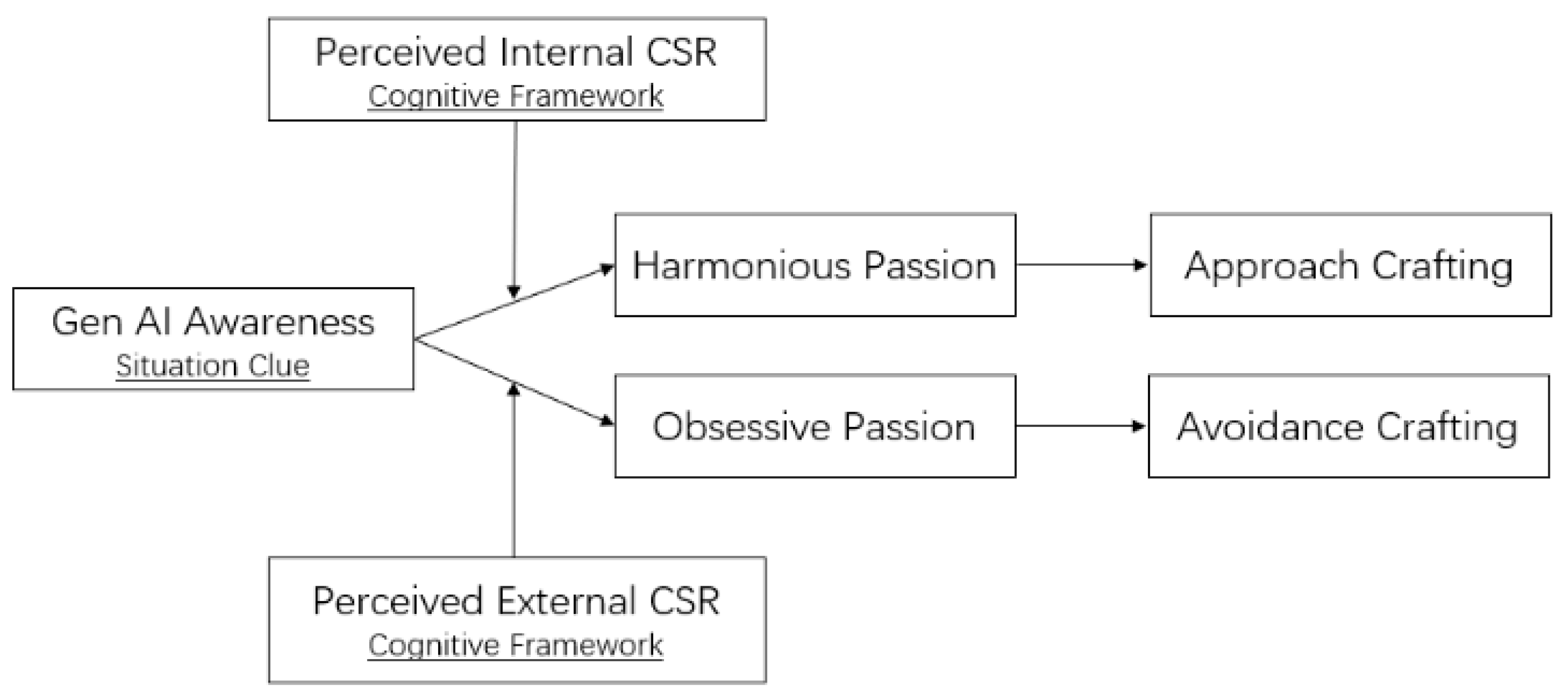

Rudolph et al., 2017), they ultimately affect an organization’s ability to profit from the implementation of GenAI. Therefore, it is essential to understand how employees respond to the disruption and transformation brought by GenAI. Do they engage in approach crafting or avoidance crafting? Moreover, what underlying mechanisms and boundary conditions shape these divergent behavioral responses? The theoretical model is presented in

Figure 1.

Scholars have previously conceptualized AI awareness (

Brougham & Haar, 2018) and demonstrated that it can trigger both positive and negative workplace behaviors. With the substantial productivity gains driven by GenAI across industries (

Noy & Zhang, 2023;

Peng et al., 2023), approximately 80% of large organizations have implemented or plan to implement GenAI, accompanied by a notable increase in related investments over the past year (

IBM, 2024). These developments have heightened employees’ awareness of GenAI. Building on prior research, we introduce the concept of GenAI awareness—defined as the employees’ subjective perception of GenAI’s impact on their careers, required skills, and potential threats. The uncertainty and complexity introduced by this profound technological revolution create an ideal context for sensemaking (

Gioia & Chittipeddi, 1991). Accordingly, we adopt a sensemaking perspective to explore how GenAI awareness gives rise to differentiated job crafting behaviors. China’s high power distance and collectivist culture make employees particularly inclined to construct meaning and identity through organizational cues and actions (

Weick, 1995). As a result, they are likely to interpret workplace changes—such as the implementation of GenAI—through the lens of perceived corporate social responsibility (CSR), that is, their beliefs about how the organization treats internal and external stakeholders (

Brown et al., 2008;

Weick et al., 2005;

Weick, 1988). Perceived CSR consists of two distinct forms. Perceived internal CSR refers to employees’ perceptions of organizational efforts aimed at supporting employee well-being (

O. Farooq et al., 2017) and may help to mitigate fears related to GenAI. In contrast, perceived external CSR reflects employees’ views of the organization’s actions toward external stakeholders (

El Akremi et al., 2018). When overly emphasized, external CSR may be seen as a sign that the organization prioritizes image or profit over employee interests, thereby intensifying threats about GenAI. Based on sensemaking theory, we propose that the interaction between GenAI awareness and perceived internal/external CSR determines whether employees experience harmonious or obsessive passion, which in turn leads to distinct patterns of job crafting behavior.

We adopt the dualistic model of passion as the mediating mechanism. Harmonious passion arises from autonomous internalization of an identity, whereby individuals willingly engage in activities they enjoy. In contrast, obsessive passion results from controlled internalization, in which identity-related pressures compel individuals to engage in those same activities (

Vallerand et al., 2003, p. 756). Prior studies on AI awareness have primarily focused on emotional and cognitive mechanisms (

Teng et al., 2023) while largely overlooking work motivation—a critical and multifaceted factor in understanding employees’ behavioral responses. Passion has been both theoretically conceptualized and empirically validated as a fundamental motivational mechanism (

Vallerand et al., 2003,

2007) and has proven effective in predicting employee behaviors such as job crafting (

X. Zhang et al., 2023). Furthermore, the construction of perceived identity is a central component of the sensemaking process (

Weick et al., 2005). The way individuals internalize work into their identities—either autonomously or in a controlled manner—is a key driver of work passion (

Vallerand et al., 2003;

Vallerand, 2015). Accordingly, work passion serves as a motivational bridge, linking GenAI awareness to job crafting through the partial process of identity construction. Building on this, we propose that the interaction between employees’ GenAI awareness and perceived CSR influences their approach or avoidance job crafting through harmonious or obsessive passion, respectively.

The main contributions are as follows: First, we contribute to the research on the impact of AI in the workplace by examining how employees’ GenAI awareness leads to different forms of job crafting behavior. In addition, we incorporate both approach and avoidance job crafting into a unified research framework to investigate the differentiated mechanisms through which GenAI awareness triggers these two orientations. By identifying the dual pathways of harmonious and obsessive passion, we offer new insights into how GenAI awareness can lead to either approach or avoidance crafting. In doing so, this study expands the empirical research on approach and avoidance job crafting and provides a more nuanced understanding of GenAI’s impact on employees’ workplace behaviors.

Second, this is the first study to apply a sensemaking perspective to explain the behavioral impact of GenAI. Drawing on sensemaking theory, we propose that perceived CSR serves as a critical interpretive framework through which employees make sense of GenAI. Unlike prior studies that conceptualize GenAI awareness as a job demand or a source of stress (

He et al., 2024;

Kang et al., 2023), we emphasize the interaction between GenAI awareness and perceived CSR in shaping whether employees perceive GenAI as a challenge or a hindrance. Furthermore, by distinguishing between internal and external CSR, we explain why employees develop different types of work passion and engage in distinct forms of job crafting. This study expands the understanding of the boundary conditions under which GenAI awareness influences employee behavior in organizations and contributes to research on how the interaction between individual and contextual factors affects job crafting.

Finally, this study adopts a motivational perspective by integrating the dualistic model of passion into the research framework, thereby enriching the understanding of the mediating mechanisms through which employees’ AI awareness influences workplace behavior. While prior research has shown that individuals interpret information and develop cognitions and attitudes during times of change, the motivational processes underlying sensemaking have been largely overlooked. By introducing work passion and using identity perception and internalization as a bridge, this study connects sensemaking theory with individual motivation and provides a better explanation for why employees interpret and respond differently to the same informational cues (e.g., GenAI). Moreover, it enhances our understanding of how and when work passion emerges, and how it subsequently influences workplace behaviors.

4. Results

The means, standard deviations, and correlation coefficients of the variables, as presented in

Table 4, fall within acceptable ranges. To assess potential multicollinearity, we calculated the variance inflation factors (VIFs) for all predictor variables (

Hair et al., 2010). The VIF values were well below the commonly accepted threshold of 5—specifically, 1.49 for GenAI awareness, 1.64 for perceived internal CSR, and 1.23 for perceived external CSR—indicating that multicollinearity was not a concern in the regression models (

Hair et al., 2010). Among the control variables, GenAI usage frequency was significantly associated with several focal constructs, including GenAI awareness (β = −0.270,

p < 0.01), perceived internal CSR (β = −0.311,

p < 0.05), perceived external CSR (β = −0.174), harmonious passion (β = −0.270 *,

p < 0.05), and approach crafting (β = −0.353,

p < 0.01). These associations were statistically controlled in all regression models.

To provide an overview of the hypothesized relationships and their empirical support,

Table 5 presents a summary of all hypotheses tested in this study.

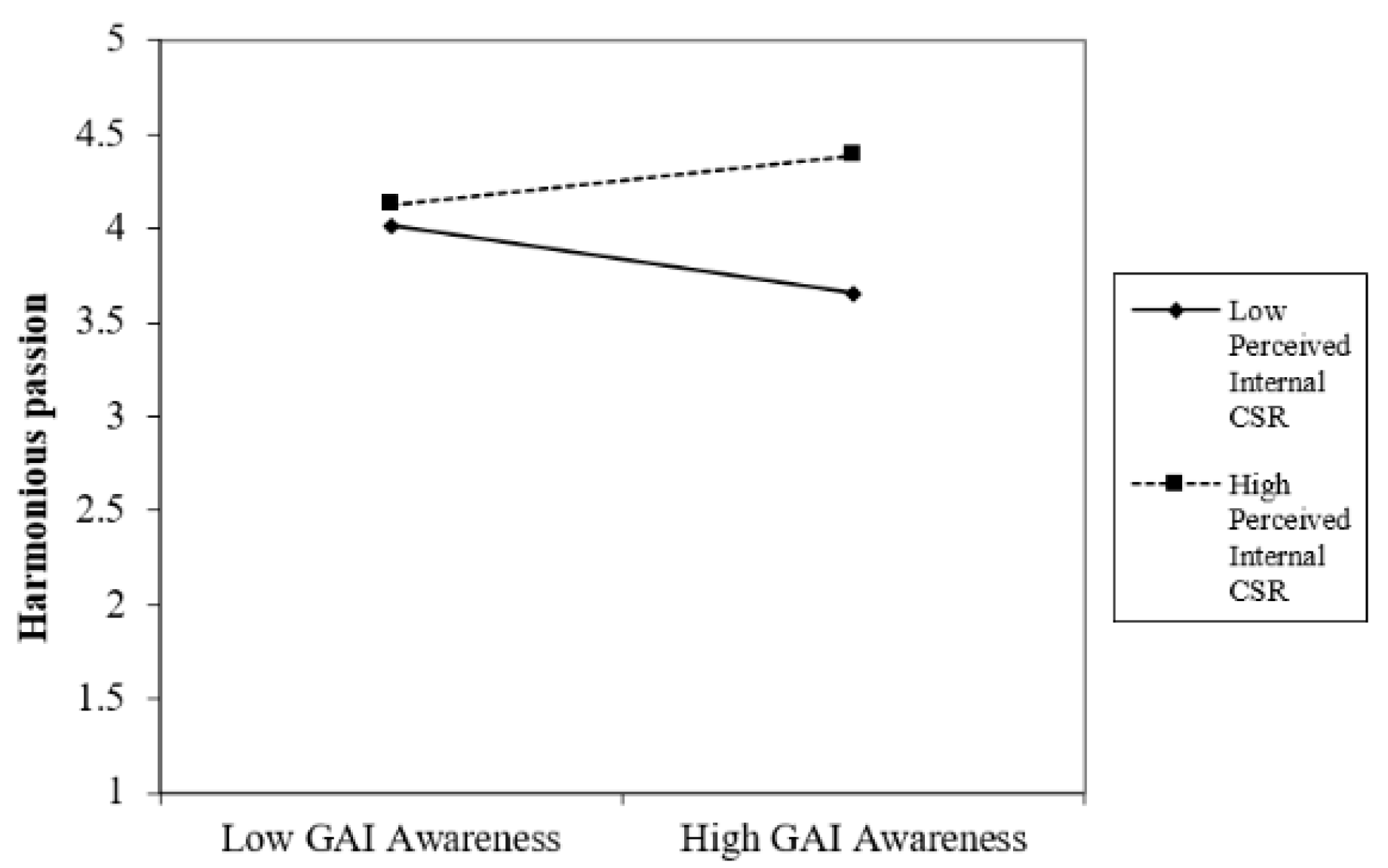

Hypothesis 1 proposed that the employees’ GenAI awareness would be positively related to harmonious passion only under a high level of perceived internal CSR. As shown in

Table 6, there was no significant main effect of the employees’ GenAI awareness on their harmonious passion (β = −0.018,

p = 0.786). However, our results showed that the employees’ GenAI awareness interacted with perceived internal CSR to predict harmonious passion (R

2 = 0.200, β = 0.532,

p < 0.001). We plotted this significant interactive effect in

Figure 2. Simple slope t tests indicated that at a lower level of perceived internal CSR (−1 SD), there was a negative relationship between the employees’ GenAI awareness and harmonious work passion (b = −0.350, t = −17.738,

p < 0.001). A positive correlation was observed at the higher level (+1 SD) of employees perceived internal CSR, when employees’ GenAI awareness was positively related to harmonious passion (b = 0.256, t = 7.351,

p < 0.001), thus Hypothesis 1 was supported.

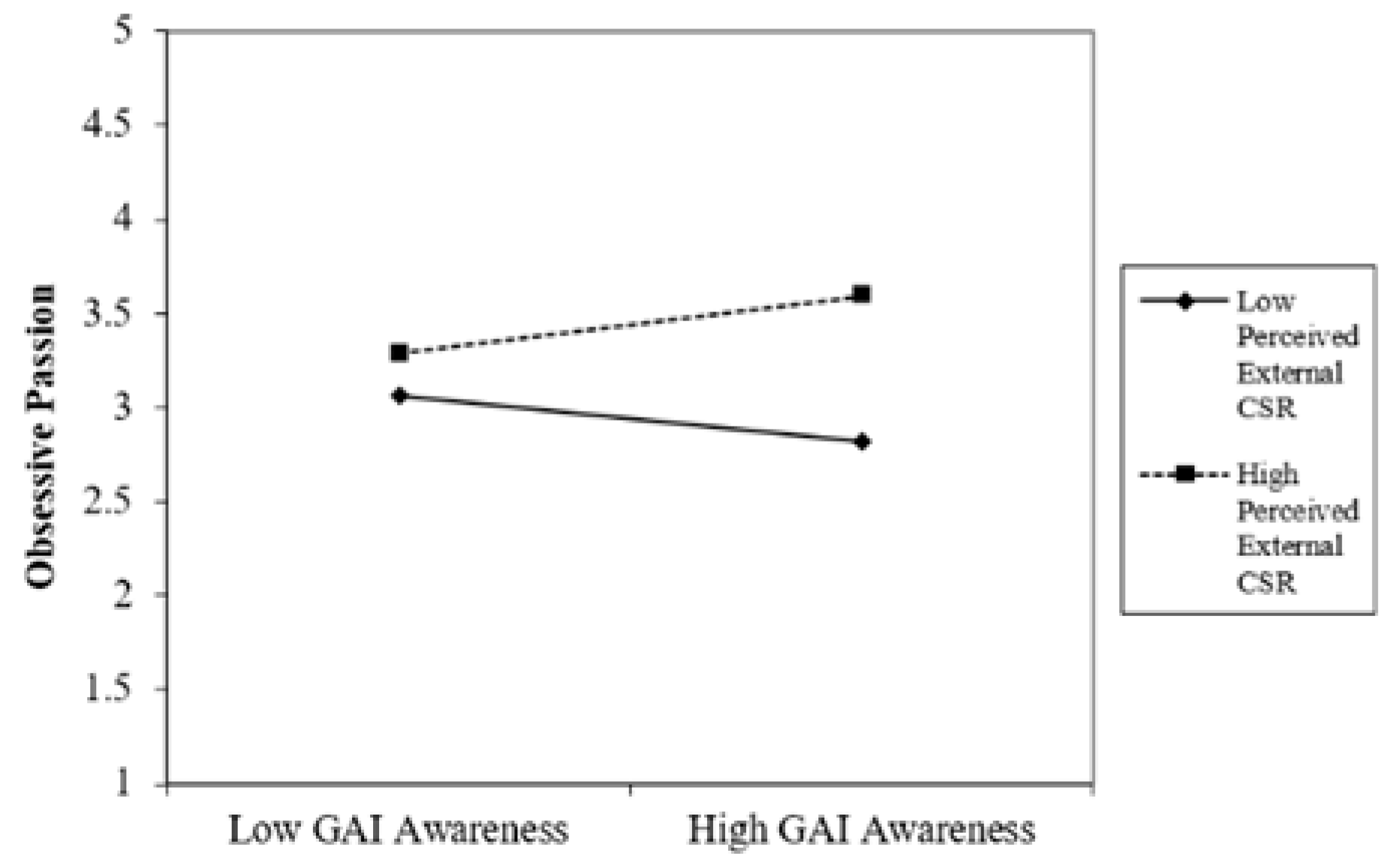

Hypothesis 2 proposed that there is a positive correlation between the employees’ GenAI awareness and obsessive work passion only when the perceived external CSR is high. As reported in

Table 6, the main effect of employees’ GenAI awareness on obsessive work passion is not significant (β = 0.116,

p = 0.317). However, the interaction between the employees’ GenAI awareness and perceived external CSR predicted obsessive work passion (R

2 = 0.086, β = 0.519,

p < 0.01). We plotted this interaction result in

Figure 3. The resulting simple slope t test showed that, under the condition of higher-level (+1 SD) perceived external CSR, employees’ GenAI awareness was positively related with obsessive passion (b = 0.295, t = 1.8354,

p < 0.05). This positive relationship turned negative under the condition of lower-level (−1 SD) perceived external CSR (b = −0.240, t = −3.208,

p = 0.001). Hypothesis 2 was thus supported.

Hypothesis 3 proposed that the employees’ harmonious work passion would be positively related to their approach job crafting. As shown in

Table 6, employees’ harmonious passion was positively related to approach crafting (R

2 = 0.216, β = 0.277,

p < 0.001). Surprisingly, we found that harmonious passion also positively predicted avoidance crafting (β = 0.177,

p < 0.001); we will explain this finding later. Hypothesis 3 was thus supported.

Hypothesis 4 proposed that the employees’ obsessive work passion would be positively related to their avoidance job crafting. As shown in

Table 6, employees’ obsessive passion was positively related to avoidance crafting (R

2 = 0.123, β = 0.166,

p < 0.001), but was not significantly related to approach crafting (β = 0.024,

p = 0.344). Hypothesis 4 was thus supported.

Hypothesis 5 proposed that the indirect effect of the interaction between employees’ GenAI awareness and perceived internal CSR on approach job crafting was mediated by harmonious work passion. Under the condition of higher-level perceived internal CSR, the positive indirect effect on approach job crafting would be stronger. As reported in

Table 7, the results showed that the interaction of employees’ GenAI awareness and perceived internal CSR had a significantly positive indirect effect on their approach crafting (ρ = 0.112,

p < 0.01, 99% CI [0.032, 0.236]) via harmonious passion. Thus, Hypothesis 5 was supported. Due to the positive relationship between harmonious work passion and approach job crafting we found previously, we further tested the interaction of employees’ GenAI awareness and perceived internal CSR on avoidance job crafting, which was also mediated by harmonious work passion (ρ = 0.075,

p < 0.01, 95% CI [0.011, 0.163]).

Hypothesis 6 proposed that the indirect effect of the interaction between employees’ GenAI awareness and perceived external CSR on avoidance job crafting was mediated by obsessive work passion. Under the condition of higher-level perceived external CSR, the positive indirect effect on avoidance job crafting would be stronger. As reported in

Table 7, the results showed that the interaction of employees’ GenAI awareness and perceived external CSR had a significantly positive indirect effect on their avoidance crafting (ρ = 0.085,

p < 0.01, 99% CI [0.012, 0.184]) via obsessive passion. Thus, Hypothesis 6 was supported.

5. Discussion

Drawing on sensemaking theory, we propose that the organizational application of GenAI represents a major situational cue that prompts employees to engage in sensemaking. In this process, employees interpret the potential impact of GenAI on their roles and identities by integrating it with their perceived CSR, thereby rationalizing their subsequent behavioral responses. Following the scan—interpret—respond sequence of sensemaking (

Weick, 1995), we develop a dual-pathway model to explain how employees’ awareness of GenAI leads to distinct forms of work passion and job crafting behavior.

Our findings support these hypotheses. The results suggest that perceived internal CSR serves as a positive interpretive frame through which employees make sense of GenAI. When employees perceive a high level of internal CSR, they are more likely to view GenAI as an opportunity for self-development or career transformation. This interpretation enables them to autonomously internalize GenAI-related work, which in turn fosters harmonious passion and leads to approach job crafting. Conversely, under high perceived external CSR, employees may interpret GenAI as a threat to their professional identity. The combination of heightened external pressure and controlled motivation triggers obsessive passion, ultimately resulting in avoidance-oriented job crafting.

Interestingly, we also observed a secondary pathway in which harmonious passion was associated with avoidance crafting. This suggests that high levels of harmonious passion may lead employees to strategically disengage from certain demands in order to conserve personal resources or maintain a work-life balance.

5.1. Theoretical Implications

Our study makes several theoretical contributions to the relevant literature.

First, we introduce the concept of GenAI awareness and examine how employees’ GenAI awareness leads to different forms of job crafting behavior. Compared to traditional AI, GenAI has had a far greater impact on the workforce by creating new job opportunities, transforming work processes, and even introducing entirely new roles. Researchers have found that human-GenAI collaboration can improve overall work efficiency (

Noy & Zhang, 2023;

Peng et al., 2023). However, it also poses challenges, such as performance decline caused by an over-reliance on GenAI and long-term skill degradation. Moreover, when tasks exceed GenAI’s capabilities, reliance on it may lead to reduced output quality (

Dell’Acqua et al., 2023). Thus, the application of GenAI in the workplace places greater emphasis on human-GenAI collaboration, offering employees more autonomy in deciding how to engage with their work. As a result, job crafting behaviors triggered by GenAI may be either approach-oriented or avoidance-oriented. While recent studies (e.g.,

He et al., 2024;

Kang et al., 2023) have investigated the impact of AI awareness on job crafting, they conceptualized job crafting as a single construct and did not consider the dual nature of approach versus avoidance strategies. By constructing a dual-pathway model of how GenAI awareness shapes employees’ job crafting behaviors, our study provides a more comprehensive perspective on the impact of GenAI awareness and extends the literature on the antecedents of both approach and avoidance job crafting.

Second, our study adopts a sensemaking theoretical perspective to explore how employees perceive GenAI awareness—either as a negative impediment or a positive challenge—and how they proactively respond to its implementation. Most previous studies have preemptively framed AI as a job demand or obstacle through resource perspectives and pressure perspectives. Using Conservation of Resources Theory (

H. T. Wang & Xu, 2023;

G. Xu et al., 2023), the JD-R model (

He et al., 2024;

Liang et al., 2022), Self-Determination Theory (

Tan et al., 2023), and Cognitive Appraisal Theory (

L. Ding, 2021;

Zhao et al., 2023), these studies describe how employees’ AI awareness, perceived as a threat to their career development or organizational status, triggers demands, stress, emotional exhaustion, and insecurity, ultimately leading to negative outcomes. However, whether in real organizational contexts or empirical studies, findings highlight diverse employee attitudes and behavioral responses toward GenAI; some perceive it as a hindrance, while others embrace it as a challenge. Given the workplace disruption brought by GenAI, employees are likely to engage in sensemaking. Drawing on sensemaking theory, this study positions perceived CSR as a cognitive framework through which employees interpret GenAI-driven changes. We demonstrate how variations in perceived CSR shape employees’ interpretations of GenAI, triggering distinct forms of work passion and job crafting behaviors. To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the impact of GenAI from a sensemaking perspective, thereby extending the application of sensemaking theory to technological change. It also validates the role of perceived CSR as an effective cognitive frame in the sensemaking process. This perspective complements existing research by integrating individual and contextual factors to explain employees’ proactive responses—specifically, approach and avoidance job crafting.

Third, our study expands the understanding of how and when work passion arises and influences workplace behaviors; through work passion, we connect sensemaking theory with motivation. Most previous studies have mainly focused on how employees’ AI awareness determines work-related behaviors through a single mediating mechanism, emphasizing emotional, cognitive, and behavioral perspectives with limited attention to the role of work motivation. However, motivation represent a more fundamental psychological mechanism compared to emotions and cognition (

Liu et al., 2011), serving as a prerequisite for stimulating employees’ proactive behaviors. We contribute to filling this gap by examining the relationship between work passion and different behavioral strategies. According to sensemaking theory, the identity construction triggered by GenAI awareness and perceived CSR will continue to unfold. As a result, employees will experience different types of work passion during the process of internalizing work into their personal identity, which will lead to approach or avoidance job crafting. We found that obsessive passion is positively correlated with avoidance job crafting, while harmonious passion positively predicts approach job crafting and is also associated with avoidance job crafting. This is because employees with high levels of harmonious passion are better at balancing their work and personal lives. When faced with significant life events or work-related stress, they might reduce their engagement with work to conserve personal resources. Overall, this study deepens our understanding of GenAI-induced work motivations and their differential effects on workplace behaviors and also enriches the research on the antecedents of job crafting.

5.2. Practical Implications

This study also offers valuable practical implications for organizations. Our findings suggest that the integration of GenAI into the workplace is more likely to trigger and amplify employees’ job crafting behaviors—both approach and avoidance—compared to tasks without AI involvement. Therefore, organizations promoting or preparing to deploy GenAI should pay close attention to employees’ GenAI awareness. Employees with a positive attitude toward GenAI tend to actively learn how to use it, collaborate with it to generate new ideas, and engage in open communication with supervisors and peers to explore innovative applications. Conversely, those with a more negative attitude may rely on GenAI primarily to reduce their workload in existing tasks, thus engaging in avoidance-oriented crafting. Therefore, organizations should not only focus on using GenAI to cut costs and improve efficiency but also pay close attention to how employees perceive and respond to this technological change. For instance, companies can host open discussions to gauge employee sentiments about GenAI, offer targeted training programs, and create opportunities for both vertical and peer-level communication to encourage approach-oriented job crafting.

In addition, we found that employee’ perceived CSR plays a crucial role in shaping the impact of their GenAI awareness on their work passion and crafting behaviors. When GenAI is integrated into work, employees who perceive internal CSR are more likely to experience harmonious passion, leading to approach job crafting, while those perceiving external CSR are more likely to experience obsessive passion, resulting in avoidance job crafting. To manage this dynamic effectively, organizations should ensure that employees feel genuinely supported and valued during technological transformations. Organizations can offer GenAI-related training programs, invite experts to provide personalized career counseling and transition planning, and grant employees greater autonomy in work design to foster a sense of control and respect. Moreover, when organizations engage in external CSR initiatives, it is critical to avoid sending signals that employee well-being is being neglected. To mitigate this risk, organizations should clearly communicate the purpose and relevance of external CSR activities—explaining how these initiatives ultimately benefit both society and employees. For instance, external CSR can enhance the organization’s long-term stability and reputation, which in turn contributes to job security and a more supportive work environment.

Moreover, our research suggests that while harmonious passion can lead to approach job crafting, it may also result in avoidance job crafting. Obsessive passion, on the other hand, exclusively leads to avoidance job crafting. Hence, organizations should aim to minimize obsessive passion while carefully managing overly high levels of harmonious passion. To achieve this, managers can foster a psychologically safe environment and offer employees a sense of autonomy and competence—two key factors that promote autonomous motivation and mitigate burnout risks (

Parker et al., 2006;

Wrzesniewski & Dutton, 2001). For example, job redesign practices that align tasks with employees’ values and interests, along with the meaningful recognition of employee efforts, can reinforce sustainable harmonious passion. In addition, organizations can provide training or coaching to help employees reflect on their passion levels, set personal boundaries, and adopt adaptive work strategies. These interventions can help employees maintain high engagement without overextending themselves.

5.3. Limitations and Future Directions

Our research provides valuable insights into the related literature but also has some limitations, which we hope will inspire further research in this area.

Firstly, while this study reveals the dual pathways through which employees’ GenAI awareness influences job crafting behaviors under different levels of perceived CSR, it does not account for the potential moderating effects of other variables. Specifically, we did not consider how individual characteristics (e.g., personality traits, career orientation), team-level factors (e.g., transformational leadership), or contextual variables (e.g., team members’ GenAI capabilities) might shape these relationships. Future research could incorporate both individual traits and contextual influences to more comprehensively identify the boundary conditions under which GenAI awareness affects job crafting behavior.

Secondly, in terms of data collection, although we employed a multi-source, multi-wave design to minimize concerns about common method bias and measurement bias, our study could not capture the temporal evolution of work passion and job crafting. Future research should explore how these dynamics unfold over time when employees collaborate with GenAI. For instance, scholars could investigate when harmonious passion becomes excessive and gradually shifts toward obsessive passion, or how harmonious passion reinforces a virtuous cycle of approach job crafting. Additionally, as all data were collected in China, the country’s unique cultural characteristics may influence how employees interpret CSR and respond to technological change. Future research should examine the interaction between GenAI awareness and perceived CSR in different national and cultural contexts to enhance the generalizability of the findings.

Lastly, while this study adapted an existing AI awareness scale to the context of GenAI, we acknowledge that the adapted measure has not undergone full psychometric validation specific to GenAI applications. Although our confirmatory factor analysis indicated acceptable reliability and model fit, future research should further assess the construct validity of the GenAI awareness scale. This could be achieved through additional validation techniques, such as convergent/discriminant validity testing or measurement invariance analysis across industries or cultural settings. Establishing a validated and domain-specific scale would strengthen the robustness and generalizability of the findings in this emerging research area.