Abstract

Psychotherapy is an essential component of mental healthcare, yet its formal instruction within medical curricula remains underdeveloped. This scoping review aimed to map the best practices for teaching psychotherapy to medical students by examining the types of psychotherapy covered and the teaching strategies employed. A systematic search was conducted across the PubMed, Embase, PsycINFO and Google Scholar databases without time restrictions, and studies were selected if they focused on psychotherapy education for medical students. Fifteen studies met the inclusion criteria. The findings revealed that multimodal approaches, combining didactic sessions, experiential learning, clinical exposure and digital content, were the most commonly used and pedagogically effective strategies. Role play and clinical exposition were particularly valued for enhancing communication skills, empathy and therapeutic understanding, while e-learning emerged as a flexible but less frequently used tool. Motivational interviewing was the most frequently taught psychotherapeutic modality, followed by mindfulness, cognitive-behavioral therapy and psychodynamic approaches. Although the overall quality of studies was moderate to high, the heterogeneity in study design and outcome measures limited direct comparisons. These results highlight the need for standardized, experiential and integrated teaching strategies to better prepare future physicians for incorporating psychotherapy principles into clinical practice.

1. Introduction

1.1. Psychotherapy

Psychotherapy is defined as a modality of treatment in which the therapist and patient work together to ameliorate psychopathologic conditions and functional impairment through focus on the therapeutic relationship and the patient’s attitudes, thoughts, affect and behavior, as well as social context and development (Brent & Kolko, 1998). Research consistently supports psychotherapy as being an effective and cost-efficient intervention for numerous psychological, behavioral and somatic conditions (Cook et al., 2017). Despite the common use of medication, addressing psychosocial factors is often essential for optimal treatment outcomes (Craighead & Craighead, 2001). Numerous meta-analyses demonstrate psychotherapy’s efficacy, sometimes yielding comparable or superior results to pharmacological treatments (Leichsenring et al., 2022; Kamenov et al., 2017). In fact, the growing body of literature highlights the importance of integrating psychotherapy into broader treatment plans to ensure long-term patient well-being and to prevent relapse in chronic mental health conditions. The development of evidence-based psychotherapeutic methods can be traced back to the early 20th century and various approaches have since been widely adopted (Marks, 2017). Over time, three major streams of psychotherapy have emerged, offering distinct perspectives on human experiences and mental health (Karasu, 1977). The first approach originates from Freud’s pioneering work, which presented a compelling framework underscoring the unconscious mind’s powerful influence on daily life (Bargh & Morsella, 2008). The second laid the foundation for the cognitive–behavioral movement, grounded in empirical observations of human behavior. The third focuses on humanistic approaches, highlighting self-determination and phenomenological perspectives in therapeutic practice (Solobutina & Miyassarova, 2019). Over the years, these methods have evolved to incorporate advancements in neuroscience, cognitive science and digital health interventions, further expanding their applicability. Psychotherapy has proven beneficial across diverse populations, regardless of age, education, ethnicity or cultural background (Kennedy et al., 2016).

1.2. Medical Education

In North America, a Doctor of Medicine (MD) degree typically takes between three and five years to complete and is usually divided into a pre-clinical phase (pre-clerkship) and a clinical phase (clerkship) (Boivin & Sakurai, 2024; McOwen et al., 2020). As an example, the University of British Columbia has a 4-year competency-based curriculum, including two years of pre-clinical training and two years of clinical training, where students rotate through various medical specialties in hospital and community settings. Similarly, at the Université de Montréal, the first-cycle doctorate in medicine is a 200-credit program consisting of a preparatory year, two years of pre-clinical training and two years of clinical training. In this case, psychiatry is covered in the pre-clinical phase through a five-week learning block that includes large-group lectures and small-group problem-based learning sessions. In the clinical phase, students complete a mandatory six-week psychiatry rotation and have the option to undertake additional psychiatry electives, ranging in duration from zero to eight weeks. Elective opportunities in psychiatry are widely available in North American medical schools, allowing students to explore various aspects of the field, including psychotherapy. However, these electives remain optional and many students choose not to pursue them, as the majority aim for a career in general practice.

1.3. Psychotherapy in Medical Education

Despite the global burden of mental illness and the recognized importance of psychosocial interventions, psychotherapy training is inconsistently integrated into undergraduate medical education worldwide. For example, while some North American and European programs offer brief exposure through electives, others (particularly in low- and middle-income countries) report minimal or no formal instruction, reinforcing a biomedical orientation and limiting future clinicians’ psychotherapeutic competencies. As another example, in North America, the practice of psychotherapy is regulated differently across U.S. states and Canadian provinces and territories. While medical graduates can usually practice psychotherapy after meeting the necessary educational and regulatory requirements, these requirements differ by jurisdiction. As an example, in the Canadian province of Québec, a permit from the Ordre des psychologues du Québec is required to practice psychotherapy, whether as a psychologist, physician, or licensed psychotherapist. In fact, all healthcare professionals, other than physicians and psychologists, seeking a psychotherapy permit must hold a master’s degree in the field of mental health and human relations and must complete 765 h of university-level theoretical training and 600 h of supervised internship specifically in psychotherapy. In this province, every medical graduate automatically obtains the right to practice psychotherapy, even though there is a significant gap between the competencies required to practice psychotherapy and the general medical curriculum. Indeed, in medical schools, psychiatry and psychological health represent only a small fraction of overall medical education (Stoudemire, 1996). Most medical students receive minimal specific training on psychotherapy, while other programs, such as psychology, are entirely dedicated to teaching and applying it (Daniel et al., 1990). As a result, many medical students perceive psychotherapy as being irrelevant to their future role as general practitioners, believing it is not a skill they can realistically develop. Therefore, many newly trained physicians may feel unprepared to integrate psychotherapeutic techniques into their practice, potentially leading to an over-reliance on pharmacological interventions when managing mental health disorders. Improving psychotherapy training in medical education is crucial to better equip future physicians with the necessary tools to address the needs of their patients, especially given that mental health concerns account for a significant proportion of consultations with family physicians. By enhancing their ability to incorporate psychotherapeutic techniques into their practice, physicians can provide more comprehensive, patient-centered care, improving the overall management of mental health.

1.4. Objectives of This Scoping Review

The objective of this scoping review is to identify the best practices in teaching psychotherapy to medical students. Specifically, it aims to determine which types of psychotherapy are covered in medical education and to explore the various teaching and learning methods used to enhance students’ psychotherapy-related skills. By mapping the existing literature on this topic, this review seeks to provide insights into effective educational approaches and contribute to the improvement in psychotherapy training in medical curricula. It is anticipated that psychotherapy training in medical schools primarily focuses on supportive therapy or motivational interviewing, with less emphasis being placed on other therapeutic models. We also hypothesize that the most effective teaching methods will likely combine structured theoretical learning with practical experiences such as role-playing or clinical simulations.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategies

A comprehensive search was conducted across the electronic databases PubMed, Embase, PsycINFO and Google Scholar from their inception to 2024. The search strategy combined medical subject headings (MeSHs) and free-text keywords related to medical students (e.g., students, medical, clinical clerkship, internships and clerkships), psychotherapy (e.g., psychotherapy, cognitive–behavioral therapy, psychodynamic, transference and defense mechanisms) and education (e.g., teaching, learning, education, medical, curriculum and training). The strategy aimed to capture a broad range of studies on how psychotherapy is taught in medical education. The complete electronic search strategy is provided in Supplementary Material S1. The search methodology was collaboratively developed by MD, an academic librarian with expertise in health sciences education. Searches were performed by MHG and were independently verified by AH in September 2024. No date, setting or geographic restrictions were applied, but only articles published in English or French were included. The PRISMA for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) was followed for this study and is reported in Supplementary Material S2. This study was not pre-registered.

2.2. Study Eligibility

Studies were eligible for inclusion if they met the following criteria: (1) the study focuses on the field of psychotherapy; (2) it focused on educational or learning strategies related to psychotherapy; (3) the population under study included medical students at any stage of their training; and (4) the article was published in English or French. Studies were excluded if they were not formally published in peer-reviewed journals (e.g., preprints), or if they were opinion pieces, book chapters or letters to the Editor. The inclusion criteria were designed to identify the peer-reviewed literature that explores concrete approaches to teaching psychotherapy within medical education, while excluding non-empirical or informal commentary.

2.3. Data Extraction

Data extraction was performed using a standardized charting table developed by the research team in Microsoft Excel (version 17.0). The following data were extracted from each included study: authors, year of publication, title, population studied (e.g., level or type of medical students), type of psychotherapy taught, teaching method used and main findings or outcomes. This approach allowed for the consistent documentation of the identified studies’ characteristics and facilitated the identification of trends across different educational strategies and psychotherapeutic approaches. Data were extracted by MHG and LRC and were verified by GL and AH to ensure accuracy and completeness.

2.4. Quality Assessment

To enhance the interpretability of the findings, a structured quality assessment of the included studies was performed using two validated tools—the Best Evidence in Medical Education (BEME) checklist and the Medical Education Research Study Quality Instrument (MERSQI) (Harden et al., 1999; Jaros & Beck Dallaghan, 2024). The BEME checklist is a broadly applicable tool that is designed to assess the methodological quality of medical education studies, regardless of study design. It consists of 11 criteria evaluating the clarity of research questions, the appropriateness of methods, context description, outcome measures and the coherence of conclusions, with each item being scored as “Yes” (1), “Partial” (0.5) or “No” (0), for a maximum score of 11. Studies scoring ≥9 were considered high quality, studies scoring 7–8.5 were considered moderate quality and studies scoring <7 were considered low quality. In addition, the MERSQI was used for studies employing quantitative methods. This instrument evaluates six domains—study design, sampling, type of data, validity of evaluation instruments, data analysis and outcome level. Each domain is scored from 0 to 3, for a total score ranging from 5 to 18. Together, these tools provided a structured evaluation of methodological rigor across a diverse set of educational studies.

3. Results

3.1. Description of Studies

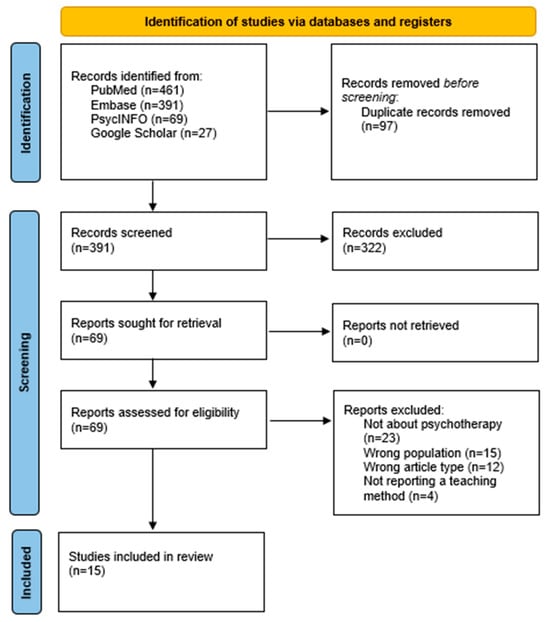

The present scoping review explored the best practices for teaching psychotherapy to medical students. An initial search across the four databases yielded 948 records. After the removal of 97 duplicate entries, 391 records were screened based on their titles and abstracts. From this initial screening, 322 records were excluded for not meeting basic inclusion criteria. A total of 69 full-text articles were then assessed in detail for eligibility. Of these, 54 were excluded for the following reasons: the article was not focused on psychotherapy (n = 23), involved the wrong population (n = 15), was of an ineligible article type such as letters or book chapters (n = 12) or did not describe a teaching method (n = 4). This screening process resulted in 15 studies being included in the final review. A detailed flowchart of the selection process is presented in Figure 1, and a full list of included studies can be found in Table 1.

Figure 1.

PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) flowchart for the inclusion of studies.

Table 1.

Summary of the identified studies.

3.2. Main Results

Among the 15 articles included in this scoping review, e-learning was identified in 4 studies, which highlighted its value as a flexible and scalable tool for delivering foundational psychotherapy knowledge. Role play was featured in nine studies, making it one of the most widely used methods; it was praised for fostering communication skills, empathy and self-reflection in a safe and engaging environment. Clinical exposition, involving direct patient interaction or observation, was also present in nine studies and was recognized for its ability to contextualize psychotherapeutic concepts and reinforce professional identity through experiential learning. Finally, multimodal approaches were the most frequently used, with 13 studies combining various techniques (such as lectures, role play, clinical exposure and digital content) to engage cognitive, emotional and behavioral domains. This layered approach was consistently associated with enhanced learner satisfaction, deeper understanding and greater readiness for clinical practice.

Across the included studies, motivational interviewing emerged as the most commonly taught psychotherapeutic approach (n = 7), valued for its brevity, structure and applicability in various clinical contexts. Motivational interview training consistently led to measurable improvements in students’ communication skills, empathy and confidence in patient-centered interactions. Mindfulness-based interventions (n = 2) and cognitive–behavioral therapy (n = 1) were also frequently integrated, often through brief workshops or structured modules, enhancing self-awareness, stress regulation and therapeutic engagement. Psychodynamic principles (n = 1), though less frequently addressed, were associated with a deeper understanding of the doctor–patient relationship and reflective practice. Four of the identified studies related to multiple therapeutic approaches.

3.2.1. E-Learning

E-learning was featured in a few studies as an accessible and scalable method for delivering foundational psychotherapy knowledge. Truong et al. reported on a randomized trial comparing computer-guided solo instruction with traditional teaching in exposure therapy, showing knowledge gains despite methodological limitations (Truong et al., 2015). Keifenheim et al. evaluated a blended-learning approach combining video modules with in-person skill sessions, which led to improved competence in motivational interviewing (Keifenheim et al., 2019). Edwards explored the integration of online materials with asynchronous discussion boards in an interprofessional training model, reporting positive engagement from learners (Edwards et al., 2022). Similarly, Katlman embedded digital tools within a psychiatric interviewing curriculum, finding increased student confidence in approaching sensitive topics (Kaltman et al., 2015). These studies demonstrate that e-learning, especially when paired with interactive elements, can be a useful adjunct for psychotherapy education.

3.2.2. Role Play

Role play was one of the most commonly used and effective teaching methods across the reviewed studies. King et al. introduced role lay-based learning (RBL) in psychiatry, where students alternated the roles of clinician and patient, leading to improvements in empathy and preparedness for clinical exams (King et al., 2015). Selzer et al. emphasized demystifying psychotherapy through metaphors and hands-on role play exercises (Selzer et al., 2015). Neufeld et al. and Muzyk et al. used structured role plays as part of SBIRT and motivational interviewing training, respectively, allowing students to simulate clinical encounters (Neufeld et al., 2012; Muzyk et al., 2019). Chéret and Buck also implemented role play within workshops on psychotherapeutic interviewing, highlighting its ability to build confidence (Chéret et al., 2018; Buck et al., 2021). McKenzie et al. indirectly evaluated the impact of experiential exposure (including role play) on students’ attitudes toward mindfulness as an intervention (McKenzie et al., 2012). Merlo et al. integrated role playing in cognitive restructuring sessions, with strong student satisfaction (Merlo et al., 2022). Truong et al. further confirmed that role play is commonly included in the most effective interventions (Truong et al., 2015). Overall, role play offers a safe space for students to develop psychotherapeutic communication and self-reflective skills.

3.2.3. Clinical Exposition

Clinical exposition (a direct interaction with or observation of patients) was highlighted as a key component in deepening students’ understanding of psychotherapy. Mintz strongly advocated for the reintroduction of psychoanalytic concepts into medical curricula through patient-centered approaches (Mintz, 2013). Neufeld et al. structured their SBIRT course around live clinical observation and patient interviews (Neufeld et al., 2012). Muzyk et al. included supervised real-patient counseling sessions with feedback, using a validated assessment tool (BECCI) (Muzyk et al., 2019). Selzer et al. argued for grounding psychotherapy concepts in clinical realities, particularly via bedside teaching and the discussion of live cases (Selzer et al., 2015). King et al. added realism by integrating role play with clinical case simulations (King et al., 2015). Chéret used real-case narratives as a base for discussion (Chéret et al., 2018). Daeppen evaluated clinical exposure during addiction-focused clerkships, demonstrating increased student motivation (Daeppen et al., 2012). Dobkin et al. involved students in mindfulness-based clinical interventions and found gains in their relational skills (Dobkin & Hutchinson, 2013). Buck used narrative exposure from psychiatric in-patients to train empathic responses (Buck et al., 2021). These examples affirm that clinical exposition is important for contextualizing theory and fostering interpersonal understanding in psychotherapy education.

3.2.4. Multimodal

Most effective programs adopted a multimodal approach, combining didactic sessions, experiential learning, reflection and clinical exposure. Mintz recommended multiple touchpoints for teaching psychodynamic principles, including lectures, case discussions and clinical integration (Mintz, 2013). Selzer et al. emphasized simplicity, clinical relevance and adaptability in combining theoretical, experiential and reflective teaching (Selzer et al., 2015). Neufeld et al. and Muzyk et al. used structured curricula that blended lectures, skills labs, patient interaction and interprofessional collaboration (Neufeld et al., 2012; Muzyk et al., 2019). Merlo et al. implemented a CBT-based session using video lectures, vignettes, group activities and role play, with excellent feedback (Merlo et al., 2022). Buck, Chéret, Edwards and Katlman all employed multiple teaching strategies (including narrative cases, peer reflection, digital tools and supervised practice), showing gains in student engagement and clinical readiness (Edwards et al., 2022; Kaltman et al., 2015; Chéret et al., 2018; Buck et al., 2021). Truong et al., in their systematic review, concluded that multimodal methods were associated with stronger learner outcomes, although few studies met rigorous standards (Truong et al., 2015). Even Keifenheim, McKenzie and Daeppen emphasized the combination of didactic, reflective and clinical components, indicating a trend toward layered learning strategies (Keifenheim et al., 2019; McKenzie et al., 2012; Daeppen et al., 2012). Multimodal formats best reflect the complexity of psychotherapy training by integrating cognitive, affective and behavioral domains.

3.3. Quality Appraisal

The BEME assessment revealed that most studies were of moderate-to-high methodological quality, with eight studies being rated as high quality and six being rated as moderate. Only one study was rated as low quality. The strongest aspects across studies were the clarity of objectives and the detailed description of the educational interventions. However, several studies showed limitations in the validity of outcome measures, data analysis transparency and, in some cases, sampling strategy. Among the quantitative studies assessed with the MERSQI, scores reflected moderate methodological appraisal, particularly in domains such as study design and outcome measurement, though external validity and instrument validation were often under-reported. These findings suggest a generally solid but heterogeneous evidence base, underscoring the need for more designed and transparently reported educational research in psychotherapy training. Table 2 represents the BEME scores, while Table 3 depicts the MERSQI assessments.

Table 2.

BEME assessments.

Table 3.

MERSQI assessments.

4. Discussion

This scoping review aimed to identify the best practices for teaching psychotherapy to medical students. A total of 15 studies were fully analyzed, revealing four main categories of teaching methods: e-learning, role play, clinical exposition and multimodal approaches. Multimodal strategies were the most frequently used and often combined lectures, clinical experiences, digital content and interactive exercises. Role play and clinical exposition were also widely implemented and valued for their ability to enhance communication skills, empathy and therapeutic understanding. E-learning was less common but offered flexibility and was often used in blended formats. The overall methodological quality of the included studies was moderate to high, based on structured evaluations using the BEME checklist and the MERSQI for quantitative studies. These findings support the integration of diverse, experience-based methods, particularly when combined, in the teaching of psychotherapy to future physicians.

In the field of medical education, various methodologies have been employed to teach psychotherapy to medical students, each with its own set of advantages and challenges. E-learning has emerged as a flexible and scalable approach in psychotherapy training. A systematic review by Mikkonen et al. evaluated e-learning programs in psychotherapy training, finding that such programs are generally associated with positive learning outcomes, including trainee satisfaction and knowledge acquisition (Mikkonen et al., 2024). The review also noted that e-learning methods often show equivalence to conventional training methods in terms of learning outcomes. However, the authors emphasized the need for further research to establish global standards for e-learning in psychotherapy education and to assess the impact on patient outcomes.

Role play is widely recognized for enhancing communication skills and empathy among medical students. Our review aligns with findings from a study by Garcia-Huidobro et al., which introduced a comprehensive therapy decision-making course incorporating various educational strategies, including application seminars that utilized role play techniques (Garcia-Huidobro et al., 2024). Students reported increased self-efficacy and perceived importance of various aspects of therapy decision-making, highlighting the effectiveness of interactive methods like role play in medical education.

Clinical exposition, involving direct patient interaction, is pivotal for contextualizing theoretical knowledge. This demonstrates that situational awareness is important to transition from theory to practice. Feller et al. demonstrated this concept in their narrative review, which aligns with the identified studies of this scoping review (Feller et al., 2023). This underscores the value of clinical exposure in mastering practical competencies that are essential for psychotherapy practice.

Multimodal approaches, which integrate various teaching methods such as lectures, role play and clinical exposure, have consistently been shown to enhance psychotherapy training. For instance, a protocol outlined by Pei et al. describes a randomized controlled trial evaluating the effectiveness of a 2-day intensive educational intervention for medical students and residents in China that combines didactic content with experiential components (Pei et al., 2025). This study reflects a growing international recognition that layered, interactive teaching strategies are essential for developing psychotherapeutic competencies. Such integrated formats not only improve knowledge acquisition but also foster empathy, self-reflection and clinical confidence, which are critical skills for patient-centered mental healthcare. As medical education evolves to meet complex psychosocial demands, multimodal approaches offer a scalable and evidence-informed path forward.

Beyond the limited inclusion of psychotherapy per se, the findings of this review reflect a deeper structural issue within medical education—the persistent privileging of biomedical interventions over psychosocial approaches. Many general physicians report comfort in prescribing psychotropic medications but hesitate to engage in psychotherapeutic conversations or techniques, not solely due to lack of technical training, but because such skills are often undervalued in their formative years. This discrepancy may stem from hidden curricula, time pressures or a perceived lack of legitimacy or ownership over psychotherapeutic care. It suggests a need not only for more content on psychotherapy, but for a cultural shift within medical education that reinforces the value of relational, empathic and psychological competencies as being a core skill in competent medical practice. Addressing this imbalance requires the deliberate integration of mental health literacy, reflective practice and psychotherapeutic principles throughout the curriculum, as well as institutional recognition of their relevance across all specialties.

It is important to highlight the limitations of this literature review. Although a comprehensive search strategy was employed across multiple databases, it is possible that relevant studies published in non-indexed journals or the gray literature were missed. While articles in both English and French were included, the exclusion of studies in other languages may have led to language bias. Also, the heterogeneity of study designs, populations and outcome measures made a direct comparison between studies difficult, limiting the ability to synthesize quantitative findings. Additionally, although a quality assessment was conducted using validated tools, the scoring remains somewhat subjective and may vary depending on interpretation. Because scoping reviews aim to map the breadth of available evidence rather than evaluate effectiveness, no conclusions can be drawn regarding the superiority of one teaching method over another. It is also important to note that most included studies assessed outcomes immediately post-intervention, limiting the ability to determine the sustainability of changes over time.

The findings of this review have implications for curriculum development in undergraduate medical education. By demonstrating the effectiveness of multimodal strategies (particularly those that incorporate active learning techniques such as role play and clinical immersion), this review supports the integration of structured psychotherapy training into core medical curricula rather than limiting it to optional electives. Educators and curriculum designers can draw on these insights to embed psychotherapeutic content longitudinally, aligning it with important developmental stages of medical training and reinforcing competencies in communication, empathy and patient-centered care. Moreover, incorporating brief, evidence-based modalities like motivational interviewing or cognitive restructuring into clinical rotations can enhance relevance and feasibility, especially in time-constrained programs. Interprofessional learning environments and blended teaching formats, including e-learning, can further increase accessibility and scalability.

To effectively implement psychotherapy training within diverse institutional contexts, medical educators should adopt scalable and adaptable strategies. For programs with limited resources, incorporating brief, low-cost interventions such as structured role play sessions during existing communication skills modules or clinical rotations can offer high-impact learning opportunities. Where faculty expertise is limited, digital resources (including recorded demonstrations, e-learning modules or online case simulations) can supplement in-person instruction. Institutions with more extensive resources may consider developing longitudinal psychotherapy tracks or elective immersion programs that integrate didactic content with supervised clinical experiences. Collaborating with departments of psychiatry, psychology or social work can also facilitate interprofessional teaching and reduce faculty burden. Regardless of setting, aligning psychotherapy training with core competencies (such as empathy, therapeutic communication and reflective practice) ensures its relevance across specialties and supports sustainability within broader medical education frameworks.

5. Conclusions

This scoping review highlights the diverse and evolving landscape of psychotherapy education for medical students, identifying four primary teaching modalities: e-learning, role play, clinical exposition and multimodal strategies. Among these, multimodal approaches emerged as the most frequently employed and pedagogically effective. Role playing and clinical immersion were particularly valuable for cultivating empathy, communication skills and therapeutic insight, while e-learning enhanced accessibility and flexibility, especially when paired with interactive formats. Although the overall quality of the included studies was moderate to high, heterogeneity in design and outcome reporting underscores the need for more methodologically rigorous and longitudinal research in this field. These findings suggest that to meaningfully improve psychotherapy training in undergraduate medical education, programs should prioritize active learning methods and embed psychotherapeutic competencies into required curricula rather than relegating them to optional electives. Faculty can leverage brief, structured interventions (such as motivational interviewing workshops or simulated patient encounters) to teach core communication and relational skills. For institutions with limited resources, blended-learning formats combining online modules with small-group discussions offer a scalable solution. Collaborations with psychiatry, psychology or social work departments can support interprofessional teaching and diversify instructional approaches. Overall, enhancing psychotherapy education equips future physicians to deliver more holistic, patient-centered care and strengthens their ability to address the complex psychosocial needs of diverse patient populations. Medical schools should view the integration of psychotherapy not as an optional enrichment, but as a foundational element of comprehensive medical training.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/bs15060780/s1 (Tricco et al., 2018).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: G.L., M.-H.G. and A.H.; methodology: M.-H.G., L.R.-C., M.D. and A.H.; validation: G.L. and A.H.; formal analysis: M.-H.G. and L.R.-C.; data curation: M.-H.G., L.R.-C. and A.H.; writing—original draft preparation: M.-H.G. and A.H.; writing—review and editing: M.-H.G., G.L., D.C., L.R.-C., M.D. and A.H.; supervision: D.C., G.L. and A.H.; project administration: A.H.; funding acquisition: A.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received indirect funding from the Fondation de l’Institut universitaire en santé mentale de Montréal.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used Antidote, version 6.1, for the purposes of proofreading. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BEME | Best Evidence Medical Education |

| CBT | Cognitive–behavioral therapy |

| MD | Doctor of Medicine |

| MERSQI | Medical Education Research Study Quality Instrument |

| MI | Motivational interviewing |

| MITI | Motivational Interviewing Treatment Integrity |

| PRISMA-ScR | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews |

| SBIRT | Screening, Brief Intervention and Referral to Treatment |

References

- Bargh, J. A., & Morsella, E. (2008). The unconscious mind. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 3(1), 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boivin, N., & Sakurai, S. (2024). 3-year medical education in North America: A student perspective. Medical Teacher, 46(6), 852–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brent, D. A., & Kolko, D. J. (1998). Psychotherapy: Definitions, mechanisms of action and relationship to etiological models. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 26(1), 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buck, E., Billingsley, T., McKee, J., Richardson, G., & Geary, C. (2021). The physician healer track: Educating the hearts and the minds of future physicians. Medical Education Online, 26(1), 1844394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chéret, A., Durier, C., Noël, N., Bourdic, K., Legrand, C., D’Andréa, C., Hem, E., Goujard, C., Berthiaume, P., & Consoli, S. M. (2018). Motivational interviewing training for medical students: A pilot pre-post feasibility study. Patient Education and Counseling, 101(11), 1934–1941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cook, S. C., Schwartz, A. C., & Kaslow, N. J. (2017). Evidence-based psychotherapy: Advantages and challenges. Neurotherapeutics, 14(3), 537–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Craighead, W. E., & Craighead, L. W. (2001). The role of psychotherapy in treating psychiatric disorders. The Medical Clinics of North America, 85(3), 617–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daeppen, J. B., Fortini, C., Bertholet, N., Bonvin, R., Berney, A., Michaud, P. A., Layat, C., & Gaume, J. (2012). Training medical students to conduct motivational interviewing: A randomized controlled trial. Patient Education and Counseling, 87(3), 313–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, D. G., Clopton, C. L., & Castelnuovo-Tedesco, P. (1990). How much psychiatry are medical students really learning?: A reappraisal after two decades. Academic Psychiatry, 14(1), 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobkin, P. L., & Hutchinson, T. A. (2013). Teaching mindfulness in medical school: Where are we now and where are we going? Medical Education, 47(8), 768–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, E. J., Arora, B., Green, P., Bannatyne, A. J., & Nielson, T. (2022). Teaching brief motivational interviewing to medical students using a pedagogical framework. Patient Education and Counseling, 105(7), 2315–2319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feller, S., Feller, L., Bhayat, A., Feller, G., Khammissa, R. A. G., & Vally, Z. I. (2023). Situational awareness in the context of clinical practice. Healthcare, 11(23), 3098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Huidobro, D., Fernandez, J., Espinosa, P., Lustig, N., Perez, I., & Letelier, L. M. (2024). Teaching therapy decision-making to medical students: A prospective mixed-methods evaluation of a curricular innovation. BMC Medical Education, 24(1), 1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harden, R. M., Grant, J., Buckley, G., & Hart, I. R. (1999). BEME Guide No. 1: Best evidence medical education. Medical Teacher, 21(6), 553–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaros, S., & Beck Dallaghan, G. (2024). Medical education research study quality instrument: An objective instrument susceptible to subjectivity. Medical Education Online, 29(1), 2308359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaltman, S., WinklerPrins, V., Serrano, A., & Talisman, N. (2015). Enhancing motivational interviewing training in a family medicine clerkship. Teaching and Learning in Medicine, 27(1), 80–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamenov, K., Twomey, C., Cabello, M., Prina, A. M., & Ayuso-Mateos, J. L. (2017). The efficacy of psychotherapy, pharmacotherapy and their combination on functioning and quality of life in depression: A meta-analysis. Psychological Medicine, 47(3), 414–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karasu, T. B. (1977). Psychotherapies: An overview. American Journal of Psychiatry, 134(8), 851–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keifenheim, K. E., Velten-Schurian, K., Fahse, B., Erschens, R., Loda, T., Wiesner, L., Zipfel, S., & Herrmann-Werner, A. (2019). “A change would do you good”: Training medical students in motivational interviewing using a blended-learning approach—A pilot evaluation. Patient Education and Counseling, 102(4), 663–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, S. H., Lam, R. W., McIntyre, R. S., Tourjman, S. V., Bhat, V., Blier, P., Hasnain, M., Jollant, F., Levitt, A. J., MacQueen, G. M., McInerney, S. J., McIntosh, D., Milev, R. V., Müller, D. J., Parikh, S. V., Pearson, N. L., Ravindran, A. V., Uher, R., & CANMAT Depression Work Group. (2016). Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) 2016 clinical guidelines for the management of adults with major depressive disorder: Section 3. Pharmacological treatments. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 61(9), 540–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, J., Hill, K., & Gleason, A. (2015). All the world’s a stage: Evaluating psychiatry role-play based learning for medical students. Australasian Psychiatry, 23(1), 76–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leichsenring, F., Steinert, C., Rabung, S., & Ioannidis, J. P. A. (2022). The efficacy of psychotherapies and pharmacotherapies for mental disorders in adults: An umbrella review and meta-analytic evaluation of recent meta-analyses. World Psychiatry, 21(1), 133–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marks, S. (2017). Psychotherapy in historical perspective. History of the Human Sciences, 30(2), 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKenzie, S. P., Hassed, C. S., & Gear, J. L. (2012). Medical and psychology students’ knowledge of and attitudes towards mindfulness as a clinical intervention. Explore, 8(6), 360–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McOwen, K. S., Whelan, A. J., & Farmakidis, A. L. (2020). Medical education in the United States and Canada, 2020. Academic Medicine, 95(9S), S2–S4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merlo, L. J., Dede, B. L., & Smith, K. B. (2022). Introduction to cognitive restructuring for medical students. MedEdPORTAL, 18, 11235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikkonen, K., Helminen, E. E., Saarni, S. I., & Saarni, S. E. (2024). Learning outcomes of e-learning in psychotherapy training and comparison with conventional training methods: Systematic review. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 26, e54473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mintz, D. (2013). Teaching psychoanalytic concepts, skills and attitudes to medical students. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association, 61(4), 751–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muzyk, A., Smothers, Z. P., Akrobetu, D., Veve, J. R., MacEachern, M., Tetrault, J. M., & Gruppen, L. (2019). Substance use disorder education in medical schools: A scoping review. Academic Medicine, 94(11), 1825–1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neufeld, K. J., Alvanzo, A., King, V. L., Feldman, L., Hsu, J. H., Rastegar, D. A., Colbert, J. M., & MacKinnon, D. F. (2012). A collaborative approach to teaching medical students how to screen, intervene and treat substance use disorders. Substance Abuse, 33(3), 286–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, T., Ding, Y., Tang, J., & Liao, Y. (2025). Evaluating the effectiveness of a multimodal psychotherapy training program for medical students in China: Protocol for a randomized controlled trial. JMIR Research Protocols, 14, e58037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selzer, R., Ellen, S., & Adler, R. (2015). Teaching psychological processes and psychotherapy to medical students. Australasian Psychiatry, 23(1), 69–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solobutina, M. M., & Miyassarova, L. R. (2019). Dynamics of existential personality fulfillment in the course of psychotherapy. Behavioral Sciences, 10(1), 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoudemire, A. (1996). Psychiatry in medical practice: Implications for the education of primary care physicians in the era of managed care: Part 1. Psychosomatics, 37(6), 502–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O’Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., Moher, D., Peters, M. D., Horsley, T., Weeks, L., Hempel, S., Akl, E. A., Chang, C., McGowan, J., Stewart, L., Hartling, L., Aldcroft, A., Wilson, M. G., Garritty, C., … Straus, S. E. (2018). PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMAScR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, A., Wu, P., Diez-Barroso, R., & Coverdale, J. (2015). What is the efficacy of teaching psychotherapy to psychiatry residents and medical students? Academic Psychiatry, 39(5), 575–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).