Abstract

Adolescence is a key period for the development and consolidation of habits that favour a healthy and active lifestyle. The promotion of healthy habits in this critical period of development is essential to ensure a better quality of life and the prevention of chronic diseases in the long term. This study aims to analyse how physical activity (PA) and adherence to the Mediterranean diet (MD) influence motivation towards physical education (PE) in adolescents. It also aims to explore gender differences and provide information that will allow the design of educational strategies to promote healthy lifestyle habits in schools. Method: descriptive cross-sectional quantitative study. An ad hoc socio-demographic questionnaire, the Physician-based Assessment and Counselling for Exercise, the KIDMED Mediterranean diet adherence questionnaire and the motivation in Physical Education questionnaire were administered in the school environment under direct supervision of the researchers to minimise biases in self-perception. Results: Students with higher adherence to the Mediterranean diet showed higher intrinsic motivation towards physical education (F = 5.133, p < 0.01), while those with lower adherence showed higher demotivation (F = 5.507, p < 0.01). Conclusions: The findings suggest the need to reinforce physical activity and nutrition education programmes in adolescents, promoting interdisciplinary approaches to increase adherence to healthy lifestyles.

1. Introduction

Adolescence is a crucial stage for acquiring long-term healthy habits, such as physical exercise and a balanced diet (Moral-García et al., 2019; Ortega et al., 2013a, 2013b; Rodríguez-Torres et al., 2024; Ruiz et al., 2009a, 2009b). However, recent decades have seen a worrying increase in sedentary lifestyles and consumption of ultra-processed foods among adolescents, which has had a negative impact on their physical and mental well-being (Blázquez et al., 2019; WHO, 2021). Factors such as technological progress (Al-Alawi et al., 2023; Mateo-Orcajada et al., 2024) and the availability of unhealthy food products have led to inappropriate lifestyles (Altavilla & Caballero-Pérez, 2019; Monteiro et al., 2019), which has increased the prevalence of obesity and metabolic diseases at an early age (Jiménez-Boraita et al., 2022; Peláez-Barrios et al., 2022).

Literature Review

Adherence to the Mediterranean diet (MD) and physical activity (PA) have been shown to be determinants in the prevention of metabolic and cardiovascular diseases in adult life (Grosso et al., 2020; Rebollo-Ramos et al., 2020). MD, recognised by WHO and FAO as one of the healthiest dietary patterns (WHO, 2021), contributes to metabolic regulation, reduced inflammation and improved mental health (Davis et al., 2021; Monteiro et al., 2019). However, recent studies have warned of a decline in adherence to MD among adolescents, especially in Mediterranean countries (Dernini & Berry, 2015; Moral-García et al., 2019), due to changes in eating habits, the influence of advertising and marketing and a preference for ultra-processed products (Carmona-Rodríguez & Anguita-Acero, 2021; Grao-Cruces et al., 2022; Lopez-Bermudez et al., 2024). This phenomenon, coupled with the reduction of PA practice in the young population, has a significant impact on quality of life and public health.

A little explored aspect in the literature is the relationship between MD, PA and motivation towards physical education (PE). Self-determination theory posits that increased intrinsic motivation towards PA promotes long-term adherence (Dorado-Cuevas et al., 2016; Ryan & Deci, 2000). Some studies suggest that a balanced diet can improve physical performance, reduce fatigue and enhance motivation for sport (Navarro-González et al., 2016; Vera-Lara & Esteves-Fajardo, 2023).

However, the interaction between these factors in the school context has not been sufficiently investigated (D. S. Teixeira et al., 2022). It is relevant to understand how eating habits may affect adolescents’ attitudes towards sport practice and their engagement in PE, a key area for the development of long-lasting healthy habits.

In addition, the physical condition has been identified as a more robust predictor of health and longevity than PA, as adequate levels of physical condition are associated with a lower incidence of cardiovascular and metabolic diseases (Gómez-Cabello et al., 2018). In this context, adherence to the MD may also play a crucial role in enhancing adolescents’ physical readiness and overall energy levels, which can directly influence their motivation towards PE. A balanced nutritional intake, rich in essential nutrients, supports cognitive performance, mood regulation and physical endurance, which are factors closely related to how students perceive and engage in PE classes. Therefore, better adherence to MD could contribute to higher levels of intrinsic and identified motivation by improving students’ perceived competence, reducing fatigue and promoting a more positive attitude towards physical activity in educational settings.

Research has pointed out that adolescents with low physical condition are at higher risk of developing obesity due to their lower ability to regulate body weight and burn calories efficiently (Jiménez-Boraita et al., 2022; Parra-Escartín & Villalobos, 2020). These findings reinforce the need for educational programmes that promote PA and the development of optimal physical condition from an early age (Melis et al., 2021). The combination of good physical condition with a balanced diet could enhance motivation and performance in PE, which underlines the need to design strategies that integrate both aspects to improve young people’s health.

Most adolescents do not meet current physical activity recommendations (Guthold et al., 2020). Regarding gender differences in the adoption of healthy habits, evidence suggests that girls tend to have greater adherence to MD and greater awareness of their health compared to boys, who tend to show a greater predisposition to risky behaviours (Román et al., 2018). These differences may be influenced by sociocultural and educational factors, highlighting the importance of designing specific interventions for each group (González-Fimbres & Cuevas-Castro, 2022; Quinde-Zambrano et al., 2024). In addition, girls tend to show greater intrinsic motivation towards PE, while boys tend to participate in sport activities for extrinsic reasons, such as competition or body image (De Vargas & Mor, 2020; Román et al., 2018). Analysing these differences will make it possible to design more effective programmes adapted to the needs of each group, in order to avoid sedentary lifestyles and increase physical activity (Bull et al., 2020).

In this context, PE plays a key role in promoting healthy habits among adolescents. In addition to promoting PA, PE can contribute to improving knowledge about balanced nutrition and self-care (Sallis et al., 2020). In parallel, school nurses play a crucial role in health education and promotion in the school environment, providing support for disease prevention and the development of effective educational programmes (Baisch et al., 2017; McClanahan & Weismuller, 2015). Through integrated strategies involving teachers, health professionals and the school community, it is possible to promote healthy habits that last throughout life (Basch, 2011; Langford et al., 2017; NASN, 2020). The implementation of early intervention programmes that promote PA and nutrition education is essential to prevent chronic diseases in adulthood and improve the quality of life of adolescents (López-Sánchez et al., 2017).

On the other hand, recent studies have highlighted the relationship between motivation towards PA and the psychological benefits it brings. It has been shown that adolescents who practice PA regularly have lower levels of anxiety and depression, as well as better emotional regulation and self-esteem (González & Pérez, 2022; Martínez, 2022; Suárez-Manzano et al., 2023; Balloo et al., 2024). This reinforces the importance of PE as a tool for improving physical health and enhancing mental and social well-being. By integrating interdisciplinary approaches that combine PA with proper nutrition, more effective educational strategies can be developed to promote healthy lifestyles from an early age (Tang et al., 2024).

Adherence to the Mediterranean diet may influence motivation toward physical education through various physiological and psychological mechanisms. A balanced diet rich in fruits, vegetables, whole grains, healthy fats and essential micronutrients not only supports overall physical fitness but also enhances energy availability and mood (Melguizo-Ibáñez et al., 2022; Trigueros et al., 2020). These factors can strengthen perceived competence, reduce fatigue and increase willingness to engage in physical effort—key components for fostering intrinsic motivation and identified regulation in physical activity (Vasconcellos et al., 2020). From the perspective of self-determination theory, proper nutrition can act as a facilitator of well-being and autonomy, promoting positive attitudes toward exercise in the educational context (P. J. Teixeira et al., 2012).

Given this context, the present study aims to analyse how PA and adherence to MD influence motivation towards PE in adolescents, taking into account gender differences. The results may contribute to the design of educational strategies that encourage healthy lifestyle habits in the school environment, promoting an interdisciplinary approach to improve physical and mental well-being in the adolescent population. Understanding these dynamics will allow the development of more effective interventions that promote sport and healthy eating in adolescence, with the aim of generating a positive impact on public health in the long term.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

A cross-sectional descriptive and correlational study was carried out with a quantitative approach (Ato et al., 2013), the aim of which was to analyse the relationship between PA practice, adherence to the MD and motivation towards PE classes in adolescents.

2.2. Sample

The initial sample was 285 schoolchildren, from which those who did not meet the inclusion criteria were excluded, resulting in 264 final participants (54.4% boys, 45.6% girls), aged between 12 and 14 years (M = 13.22, SD = 1.36), from two urban schools in the province of Salamanca, Spain.

The selection was made by non-probabilistic convenience sampling, based on the accessibility of the schools and the feasibility of data collection within the established period. Although this strategy facilitates participation and study logistics, it has limitations in terms of generalising results to larger populations. To minimise potential selection bias, we included centres with diverse socio-demographic characteristics and ensured heterogeneity in the sample in terms of gender and level of physical activity.

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Data collection was carried out during the academic year 2023–2024 and the following inclusion criteria were established:

- -

- Adolescents attending school in the selected educational centres.

- -

- Ages 12–14 years: the 12–14 age group was selected due to the transition stage between primary and secondary education, a time when healthy lifestyle habits are consolidated.

- -

- Informed consent signed by legal guardians.

- -

- Regular class attendance and willingness to complete the questionnaires.

Participants were excluded from the study if they had the following:

- -

- Chronic diseases, musculoskeletal disorders or medical restrictions preventing regular PA practice.

- -

- Incomplete questionnaires or inconsistent responses.

2.4. Instruments

The following validated questionnaires were used for data collection:

First, an ad hoc socio-demographic questionnaire was implemented which collected information on age, gender and physical activity habits. To analyse the level of PA practice, the Physician-based Assessment and Counseling for Exercise PACE questionnaire (Prochaska et al., 2001) was used to assess the days of PA practice for at least 60 min in a normal week and in a week following the WHO recommendations. After averaging both weeks, participants were classified into two groups: active (meeting WHO recommendations) and inactive (not meeting WHO recommendations) (WHO, 2020).

Adherence to MD was assessed using the KIDMED Mediterranean diet adherence questionnaire (López-Gajardo et al., 2022; Serra-Majem et al., 2004), widely used with Spanish adolescents (Grao-Cruces et al., 2013; Hernández et al., 2020; Herrera-Ramos et al., 2023; López et al., 2020). It is an instrument of 16 dichotomous response questions (yes or no), where affirmative answers (yes) add one point (items 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 8, 9, 10, 11, 13 and 15) and negative answers (no) subtract one point (items 6, 12, 14 and 16). The sum of the scores for each response allows classifying schoolchildren into three categories:

- -

- Optimal or high adherence (score ≥ 8 points);

- -

- Intermediate adherence (score between 4–7 points);

- -

- Low adherence (score ≤ 3 points).

Finally, the Motivation in Physical Education Questionnaire (CMEF) developed by Sánchez-Oliva et al. (2012) was used to assess motivation in physical education classes. This questionnaire begins with the sentence ‘I participate in physical education classes…’ followed by twenty items measuring five factors. The factors showed adequate reliability indices, with Cronbach’s alpha coefficient values ranging from 0.77 to 0.83: motivación intrínseca (items 1, 6, 11 and 16; α = 0.83).

- -

- Identified regulation (items 2, 7, 12 and 17; α = 0.80);

- -

- Introjected regulation (items 3, 8, 13 and 18; α = 0.77);

- -

- External regulation (items 4, 9, 14 and 19; α = 0.80);

- -

- Demotivation (items 5, 10, 15 and 20; α = 0.78).

2.5. Procedure

First, the study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Burgos, following the ethical standards established in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent revisions (WMA, 1964). In addition, the guidelines for research with minors were established by and complied with the American Psychological Association (American Psychological Association, 2020).

A standardised protocol for data collection was designed to ensure homogeneity in the participation of all subjects. The principal investigator contacted the selected schools beforehand to inform them about the objectives and procedures of the study.

Once the secondary schools had given their approval, the nature of the study was explained in detail to the teachers and an informed consent form was distributed to parents or legal guardians, as all participants were minors. This consent, necessary to authorise the students’ participation, included information on the aims of the research, confidentiality of the data and the right to withdraw from the study at any time without consequences.

Subsequently, students were informed about the purpose of the study and were guaranteed anonymity and confidentiality in the treatment of their responses.

The questionnaires were completed in the classroom, under the direct supervision of one of the researchers, who was present to resolve any doubts or incidents that might arise during data collection.

This process was carried out in an estimated time of 10–15 min, ensuring a controlled and homogeneous environment for all participants.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

First, the data were described using means, standard deviations and frequencies, and the chi-square test was used to compare the frequencies of variables between groups (gender). Subsequently, a preliminary analysis was performed to check whether the data followed a normal distribution, as this is a prerequisite for certain statistical analyses. For this purpose, the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used, which assesses whether the data differ significantly from a normal distribution. Since the sample exceeded 50 participants (n = 264), this test was adequate and showed that the data met this assumption.

Homoscedasticity, which refers to the variability of the data being similar across the different groups analysed, was also tested for homoscedasticity. This was assessed with Levene’s test.

Additionally, independent samples t-tests were used to compare continuous motivation variables (CMEF dimensions) between boy and girl participants, as shown in Table 1. This test allowed us to detect gender-based differences in intrinsic, identified, introjected, external motivation and demotivation scores.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of physical activity level, Mediterranean diet adherence and motivation towards physical education in adolescents aged 12–14 years.

To analyse whether there were differences between the groups, an analysis of variance (ANOVA), which compares the means of several groups to identify significant differences, was used. In this case, the dimensions of the CMEF were the dependent variables, while gender and adherence to the MD acted as independent variables. In addition, post-hoc tests (Bonferroni) were performed, which allow individual groups to be compared in order to identify which ones show significant differences. Although a full factorial 2 × 2 × 2 × 2 design could provide deeper insight into interaction effects among variables such as sex, physical activity level and adherence to the Mediterranean diet, this study employed a non-experimental, cross-sectional design with convenience sampling. Given these characteristics and the sample size distribution across groups, the use of ANOVA, multiple linear regression and ANCOVA was deemed appropriate and statistically robust to examine main effects and control for covariates. Future research with larger and more balanced samples may benefit from implementing a factorial design to explore complex interaction patterns in greater depth.

Subsequently, multiple linear regression was performed to analyse the extent to which PA and adherence to MD can predict motivation towards PE classes. To ensure the validity of the model, the model was checked for error independence, assessed by the Durbin–Watson test, which indicates that the residual values of the model are uncorrelated, and for collinearity, using the tolerance and VIF (Variance Inflation Factor) values, which indicate whether there is an excessive relationship between the independent variables, which could distort the results.

Finally, an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was carried out, which is an extension of ANOVA that allows the effect of other variables on the variable of interest to be controlled. In this case, the dimensions of the CMEF were established as dependent variables, and adherence to MD and the level of PA practice as covariates, segmented by sex.

Data were analysed with the SPSS statistical package, version 28.0 for Windows (IBM, Chicago, IL, USA). The level of statistical significance adopted was p < 0.05, with a 95% confidence interval.

2.7. Ethical Aspects

The ethical and deontological principles established by the American Psychological Association (American Psychological Association, 2020) were followed in this research. Approval of the research protocol was requested from the Ethics Committee of the University of Burgos, which granted approval under the code 2024/REGSED-2113/Nº IO 18/24. All participants signed an informed consent form as part of the inclusion criteria (American Psychological Association, 2020).

3. Results

A preliminary analysis of the data was performed to verify the fulfilment of the statistical assumptions necessary for the subsequent analyses. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test indicated that the data followed a normal distribution (p > 0.05). In addition, homoscedasticity was tested using Levene’s test, with no significant differences found in the variance of the groups (p > 0.05), allowing the application of parametric tests.

Descriptive analysis showed that 73.45% of men and 67.6% of women were inactive, while 26.64% of men and 32.4% of women were classified as physically active, with significant differences between sexes (χ2 = 7.12, p = 0.003). Regarding adherence to MD, 31.2% of men and 31.9% of women had optimal adherence, with no significant differences between sexes (χ2 = 3.25, p = 0.177) (Table 1).

In terms of motivation towards PE lessons, girls seem to feel more identified motivation than boys (p < 0.01; 4.10 vs. 3.90), while boys claim to be more unmotivated than girls (p < 0.01; 1.97 vs. 1.42).

The analysis of variance (Table 2) showed significant differences in motivation towards PE according to gender. Girls reported significantly higher identified motivation than boys (F = 1.625, M = 4.10 vs. 3.90; p < 0.05), while boys reported higher levels of demotivation compared to girls (F = 5.353, M = 1.67 vs. 1.41; p < 0.05).

Table 2.

ANOVA between the dependent variables associated with the dimensions of the CMEF questionnaire and the independent variable sex.

Adolescents with optimal adherence showed higher intrinsic motivation towards PE (F = 5.133, M = 4.36 vs. 3.81; p < 0.01), while those with low adherence showed significantly higher levels of demotivation (F = 5.507, M = 2.03 vs. 1.60; p < 0.01). Likewise, identified motivation was higher in students with optimal adherence compared to those with low adherence (F = 9.207, M = 4.19 vs. 3.42; p < 0.001) (Table 3).

Table 3.

ANOVA between the dependent variables associated with the dimensions of the CMEF questionnaire and the independent variable adherence to the Mediterranean diet.

To determine the impact of adherence to MD and PA on motivation in EF, a multiple linear regression analysis was performed. It was found that better adherence to MD predicted higher intrinsic motivation in boys (β = 0.245, p = 0.014) and higher identified motivation in both sexes (boys: β = 0.338, p = 0.001; girls: β = 0.303, p = 0.022). In terms of PA, physically active adolescents were found to be more intrinsically motivated (β = 0.441, p = 0.021).

Regression analysis showed that boys with optimal adherence to MD had significantly higher levels of introjected motivation (β = 0.301 ± 0.115; p = 0.009). In contrast, boys with low MD adherence were the most unmotivated (β = −0.341 ± 0.111; p = 0.003).

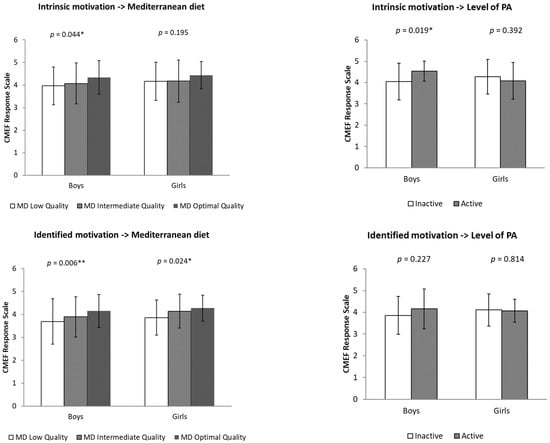

Analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) revealed that boys with optimal adherence to MD showed significantly higher levels of intrinsic motivation than those with low adherence (p = 0.004). In addition, physically active adolescents showed higher identified motivation compared to inactive adolescents (p = 0.019). However, no significant differences in extrinsic motivation were found according to the level of PA or adherence to MD.

ANCOVA analysis showed significant differences in identified motivation in both sexes. Both boys (p = 0.006) and girls (p = 0.024) with optimal adherence to MD had higher levels of identified motivation compared to those with low adherence (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Differences in levels of intrinsic and identified motivation for physical education classes (CMEF questionnaire) according to adherence to the Mediterranean diet (low, intermediate and optimal quality) and physical activity level (inactive and active), segmented by sex (boys and girls). Note: * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.001.

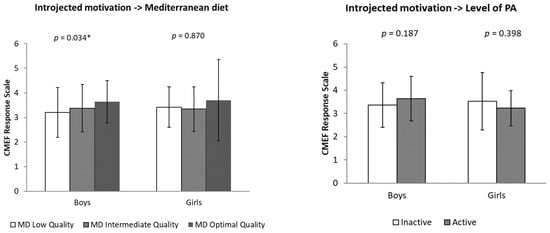

In terms of introjected motivation, significant differences were found only in the boy group (p = 0.034), where boys with optimal adherence to MD showed higher levels of this motivational dimension than those with low adherence. No significant differences in introjected motivation were found in the girl’s group.

With respect to external motivation, no significant differences were observed according to sex, adherence to MD or level of PA. However, the data suggest a slightly higher trend in boys with optimal adherence to MD and physically active, whereas, in the case of girls, this trend is reversed (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Differences in levels of introjected and external motivation for physical education classes (CMEF questionnaire) according to adherence to the Mediterranean diet (low, intermediate and optimal quality) and physical activity level (inactive and active), segmented by sex (boys and girls). Note: * p < 0.05.

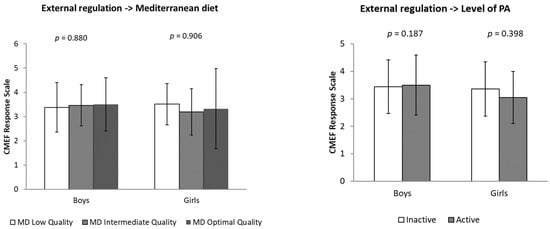

ANCOVA analysis revealed that boys with low adherence to MD showed significantly higher levels of demotivation compared to those with optimal adherence (p = 0.011). In the girl’s group, no significant differences were found in the levels of demotivation according to MD adherence.

Likewise, no significant differences were observed in demotivation according to PA level. However, within the boy group, inactive adolescents presented the highest levels of demotivation (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Differences in levels of demotivation towards physical education classes (CMEF questionnaire) according to adherence to the Mediterranean diet (low, intermediate and optimal quality) and physical activity level (inactive and active), segmented by sex (boys and girls). Note: * p < 0.05.

4. Discussion

The results of this study confirm that adolescents with greater adherence to the MD and adequate levels of PA have higher levels of intrinsic motivation towards PE classes. This result coincides with the findings of De Vargas and Mor (2020), who highlight a positive relationship between healthy lifestyle habits and self-determined motivation. Likewise, Castillo et al. (2007) and Ryan and Deci (2000) have pointed out that a healthy environment can facilitate the development of more autonomous motivations towards sport practice.

4.1. Core Findings

First, it was observed that boys presented significantly lower levels of PA compared to girls, which is consistent with previous studies that have reported lower participation of boys in structured physical activities (Grao-Cruces et al., 2022; Cocca et al., 2025). Research such as Álvarez-Ibáñez and Fernández-Hawrylak (2024), Tremblay et al. (2017) and Serrano et al. (2017) have suggested that these differences may be due to sociocultural factors and perceptions of physical competence. Conversely, some studies in different contexts have pointed to greater female inactivity, suggesting that these differences may be due to socio-cultural factors and perceptions of physical competence. This finding suggests the need to design specific strategies that encourage the participation of adolescent girls in PA, adapting the contents of PE to their interests and promoting an inclusive environment (Barcala-Furelos et al., 2024; Martínez-Gómez et al., 2022).

Overall, however, the participants do not comply with World Health Organization (WHO, 2020) guidelines that recommend that adolescents perform at least 60 min of moderate to vigorous intensity PA daily, as well as activities that strengthen muscles and bones at least three days a week.

Regarding adherence to MD, no significant differences were found between sexes. However, it was identified that adolescents with greater adherence to MD showed greater intrinsic motivation and less demotivation in PA, which is in agreement with De Vargas and Mor (2020) and D. S. Teixeira et al. (2022). This finding can be explained by the positive effect of a balanced diet on energy, mood and physical performance (Grosso et al., 2020; Davis et al., 2021).

It should be noted that technological advances have led to an increasingly inactive lifestyle, which has led to a decrease in the practice of PA among adolescents (Maldonado, 2023). In parallel, the increase in the consumption of ultra-processed products has reduced the nutritional quality of the diet of young people, affecting not only their physical health, but also their energy and willingness to practice PA (Monteiro et al., 2019). In this study, it was observed that adolescents with lower adherence to MD presented lower levels of intrinsic motivation, underscoring the importance of nutrition education as a complement to PA promotion in the school environment.

Similarly, it coincides with previous research that has linked healthy eating with better emotional regulation and greater engagement in physical activity (Grosso et al., 2020; Ruggiero et al., 2021). Studies such as that of Davis et al. (2021) have shown that nutrients present in MD can influence energy levels and mood, which could explain this relationship. Furthermore, it not only impacts metabolic health, but also influences sleep quality, muscle recovery and emotional well-being (Estrada et al., 2023; Jiménez et al., 2022; Ghasemi et al., 2024).

This study provides further evidence of this relationship by finding that adolescents with greater adherence to the MD presented greater motivation towards PE. This suggests that a balanced diet not only improves physical performance but may also play a key role in the perception of PA as a pleasurable and sustainable activity over time.

Furthermore, regression analyses showed that greater adherence to MD was associated with greater identified and introjected motivation, especially in boys. This result indicates that adolescents who understand the benefits of healthy eating tend to show a greater willingness to participate in PA, which reinforces the need to promote healthy habits from an early age and to integrate nutrition education programs in the school environment, not only to improve physical health, but also to enhance the active participation of students in PE.

In line with this, previous research has shown that eating habits influence the disposition towards PA, highlighting the relationship between the consumption of balanced diets and better sports performance (Navarro-González et al., 2016; Vera-Lara & Esteves-Fajardo, 2023). On the other hand, boys with low adherence to MD presented significantly higher levels of demotivation, which could be due to lower available energy and a negative perception of PA. This finding aligns with Díaz-Quesada et al. (2024), who suggest that unhealthy eating can negatively impact on energy and perceived PA.

The ANCOVA analysis also showed that physically active adolescents presented higher levels of intrinsic motivation than inactive adolescents. This finding suggests that PA practice can strengthen autonomy and enjoyment in EF, which is consistent with Self-Determination Theory (Cádiz-Chacón et al., 2021; Deci & Ryan, 2000; Dorado-Cuevas et al., 2016; Ryan & Deci, 2000).

In addition, recent studies highlighted motivation as a predictor of long-term adherence to PA (Ali et al., 2023; Fernández-Espínola et al., 2021; D. S. Teixeira et al., 2022). It is also evident that inactive boys are the most unmotivated, which underlines the need for specific strategies to encourage their participation in the school environment, a trend that has also been observed in research on the impact of educational methodology on motivation towards PE (Heredia-León et al., 2023; Mayor-Díez et al., 2024).

Finally, gender differences in motivation for PE reflect trends already observed in previous studies. It has been observed that women tend to be more health conscious and follow healthy eating patterns (De Vargas & Mor, 2020), whereas men tend to be more oriented towards extrinsic motivations for the practice of PA, such as competition or body image (Román et al., 2018). These results highlight the need to design differentiated strategies to promote PA in both sexes, taking into account their specific motivations and reinforcing the role of PE as an inclusive and motivating space for all adolescents.

In conclusion, this study confirms that greater adherence to MD and PA is associated with greater motivation in EF, especially intrinsic and identified motivation. These results underline the importance of implementing integrated educational programs that simultaneously promote healthy eating habits and an active lifestyle. Designing specific strategies in the school setting could contribute significantly to the improvement of adolescents’ well-being and foster their long-term commitment to PA.

It has been argued that physical condition is a stronger predictor of health and longevity than PA itself, as it influences not only cardiovascular and metabolic capacity but also overall well-being (Suárez-Manzano et al., 2023). Although our study did not directly measure physical fitness, the observed associations between PA and higher levels of motivation toward physical education highlight the importance of promoting active lifestyles among adolescents. These findings indirectly support the need for school programs that go beyond sports practice and aim to foster sustained engagement in PA, which may, in turn, contribute to improvements in physical fitness and long-term health outcomes.

Interdisciplinary collaboration between the different members of the educational team, integrating teachers, psychologists and nursing staff, will be essential to ensure that students not only receive a quality academic education, but also the comprehensive support needed to maintain optimal physical and mental health. This joint approach will allow us to more effectively address the needs of students, promoting their well-being from a holistic perspective that combines academic development with the promotion of healthy habits and emotional care.

4.2. Practical Implications, Limitations and Future Directions

Firstly, it should be noted that the results of this study have direct applications in the design of school programmes, educational policies, health promotion strategies and intervention programs in adolescence, and highlight the need to promote initiatives focused on physical education and sports within today’s society to improve the physical condition and overall well-being of young people. The most effective measures to achieve these objectives include increasing the number of hours of PE in the school curriculum and ensuring that classes foster intrinsic motivation in students.

Likewise, it is essential to design and implement interdisciplinary educational programs that comprehensively address healthy lifestyle habits. These actions would not only contribute to improving the general health status of the youth population, but could also have a positive impact on their quality of life in the long term.

However, despite the robustness of the findings, it is important to recognise the limitations of the study.

First, the use of convenience sampling may affect the generalisability of the results; future research could employ stratified random sampling to improve representativeness. Second, the cross-sectional design prevents the establishment of causal relationships between variables such as physical activity, adherence to the Mediterranean diet, and motivation toward physical education.

Third, the reliance on self-reported questionnaires may introduce biases related to social desirability or inaccurate recall, particularly in adolescent populations.

Lastly, the study did not include objective measures of physical fitness, which could provide a more comprehensive understanding of the links between lifestyle habits and motivation in PE contexts. These limitations should be considered when interpreting the results and designing future interventions.

Furthermore, this study opens up new avenues of research into the complex interaction between psychological, nutritional and physical factors in the adolescent population. Future studies should consider examining the influence of the family environment, perceptions of physical competence and teaching methodologies in physical education, as these elements may offer a more comprehensive and nuanced understanding of the determinants of motivation. This knowledge could serve as a basis for developing more effective strategies to promote healthy lifestyle habits among young people.

In summary, this study provides evidence on the relationship between PA, adherence to MD and motivation towards PE, highlighting the importance of implementing comprehensive strategies at school and community level to promote healthy lifestyles in adolescents. It reinforces the need to implement coordinated actions between the educational, health and political sectors to ensure that young people develop habits that contribute to their physical and mental well-being throughout their lives.

5. Conclusions

The findings of this study demonstrate that greater adherence to the Mediterranean diet and regular physical activity are positively associated with higher levels of motivation towards physical education, particularly in its intrinsic and identified dimensions. These results underscore the need to design and implement integrated educational programs that simultaneously promote healthy eating habits and active lifestyles from an early age.

Moreover, the practical implications of these findings extend to educational policies and public health strategies, particularly those aimed at fostering long-term engagement in physical activity during adolescence. In this regard, increasing the number of physical education hours in school curricula and structuring sessions to enhance students’ intrinsic motivation are essential measures. Such initiatives not only contribute to improved physical fitness and overall well-being among youth but also support the development of long-lasting healthy behaviours.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, P.S.M.G. and M.A.J.; methodology, R.A.d.B. and J.E.M.G.; software, R.A.d.B. and J.E.M.G.; validation, P.S.M.G., M.A.J., R.A.d.B. and J.E.M.G.; formal analysis, R.A.d.B. and J.E.M.G.; investigation, P.S.M.G., M.A.J., R.A.d.B. and J.E.M.G.; resources, P.S.M.G. and M.A.J.; data curation, P.S.M.G. and R.A.d.B.; writing—original draft preparation, P.S.M.G. and R.A.d.B.; writing—review and editing, P.S.M.G. and R.A.d.B.; visualisation, M.A.J. and J.E.M.G.; supervision, P.S.M.G., M.A.J., R.A.d.B. and J.E.M.G.; project administration, P.S.M.G., M.A.J., R.A.d.B. and J.E.M.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Burgos (protocol code 2024/REGSED-2113/Nº IO 18/24 and date of approval 15 March 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MD | Mediterranean diet |

| PA | Physical activity |

| PE | Physical education |

| CMEF | Motivation in Physical Education Questionnaire |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Al-Alawi, L., Al Shaqsi, J., Tarhini, A., & Al-Busaidi, A. S. (2023). Using machine learning to predict factors affecting academic performance: The case of college students on academic probation. Education and Information Technologies, 28, 12407–12432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, L. A. M., Khaled, S. M., Alhussaini, N. W. Z., & Abdel-Rahman, M. E. (2023). Association between health information seeking and behaviour change related to physical activity among Qatari adolescents. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 28(1), 2273398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altavilla, C., & Caballero-Pérez, P. (2019). An update of the KIDMED questionnaire, a mediterranean diet quality index in children and adolescents. Public Health Nutrition, 22(14), 2543–2547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychological Association. (2020). Publication manual of the American Psychological Association (7th ed.). American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Ato, M., López-García, J. J., & Benavente, A. (2013). A classification system for research designs in psychology. Anales de Psicología, 29(3), 1038–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Ibáñez, D., & Fernández-Hawrylak, M. (2024). Socio-demographic factors conditioning physical activity levels in primary school students. Revista Iberoamericana de Ciencias de la Actividad Física y el Deporte, 13(1), 68–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baisch, M. J., Lundeen, S. P., & Murphy, M. K. (2017). Evidence-based research on the value of school nurses in an urban school system. The Journal of School Health, 81(2), 74–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balloo, K., Delaney, P., Hosein, A., & Liza, F. F. (2024). Trends and global power of research on physical activity, depression, and anxiety in adolescents and young adults: Science mapping the literature. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 29(1), 2375356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barcala-Furelos, M., Cendoya Ochoa, L., Pascual Torre, A., & Ramos Álvarez, O. (2024). Physical-sports activity in compulsory secondary education: Gender differences in the abandonment of regular physical activity. EDUCA. International Journal for Educational Quality, 4(2), 329–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basch, C. E. (2011). Healthier students are better learners: A missing link in school reforms to close the achievement gap. Journal of School Health, 81(10), 593–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blázquez, D., Domedel, N., Sáez de Ocáriz, U., & Supital, R. (2019). Childhood obesity and sedentary lifestyles: What do we do? Proposals and activities for school age. Inde. [Google Scholar]

- Bull, F. C., Al-Ansari, S. S., Biddle, S., Borodulin, K., Buman, M. P., Cardon, G., Carty, C., Chaput, J. P., Chastin, S., Chou, R., Dempsey, P. C., DiPietro, L., Ekelund, U., Firth, J., Friedenreich, C. M., Garcia, L., Gichu, M., Jago, R., Katzmarzyk, P. T., … Willumsen, J. F. (2020). World Health Organization 2020 guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 54(24), 1451–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmona-Rodríguez, M., & Anguita-Acero, J. M. (2021). The impact of advertising on the eating habits of Spaniards: A question of food education. Revista de Comunicación y Salud, 11(1), 29–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo, I., Balaguer, I., & García-Merita, M. (2007). Effect of physical activity practice and sport participation on healthy lifestyle in adolescence as a function of gender. Revista de Psicología del Deporte, 16(2), 201–210. [Google Scholar]

- Cádiz-Chacón, P., Barrio-Mateu, L. A., León-Valladares, D., Hernández-Sánchez, Á., Milla-Palma, M., & Sotomayor-Fernández, M. (2021). Contextual motivation from self-determination in physical education classes. Retos, 41, 88–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cocca, A., Cocca, M., Greier, K., & Ruedl, G. (2025). Structured and unstructured physical activity habits: A study on adolescents’ motivational characteristics for exercising. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 30(1), 2446462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, C., Bryan, J., Hodgson, J., & Murphy, K. (2021). Definition of the mediterranean diet: A literature review. Nutrients, 13(6), 9139–9153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “What” and “Why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11, 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dernini, S., & Berry, E. M. (2015). Mediterranean diet: From a healthy diet to a sustainable dietary pattern. Frontiers in Nutrition, 2, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vargas, J. F., & Mor, E. M. H. (2020). Motivation towards physical education and habitual physical activity in adolescents. Agora for Physical Education and Sport, 22, 187–208. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz-Quesada, G., Muñoz-Galiano, I. M., Escarabajal-Arrieta, M. D., & Torres-Luque, G. (2024). Physical activity practice and level of adherence to the Mediterranean diet in university students. Journal of Sport and Health Research, 16(1), 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorado-Cuevas, E., Paramio-Pérez, G., & Almagro, B. J. (2016). Análisis de la motivación en las clases de Educación Física en Primaria. e-Motion: Revista de Educación, Motricidad e Investigación, 1(7), 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrada, E. Y., Veytia, M., Guadarrama, R., & Pérez, M. (2023). Role of healthy and unhealthy eating in the level of subjective well-being experienced by adolescents and adults. A systematic review. Contemporary Dilemmas Journals: Education, Politics and Values, 3(58), 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Espínola, C., Jorquera-Jordán, J., Paramio-Pérez, G., & Almagro, B. J. (2021). Psychological needs, motivation and intention to be physically active in physical education students. Journal of Sport and Health Research, 13, 467–480. [Google Scholar]

- Ghasemi, P., Eslami, A. A., & Mazaheri, M. A. (2024). How did adolescent students assess their sleep patterns, sleep hygiene, physical activity, and health during the COVID-19 pandemic? A look at the effects of gender and socioeconomic status. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 29(1), 2365880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, M., & Pérez, L. (2022). Physical activity, nature and mental well-being: A systematic review. Revista de Psicología del Deporte, 31(2), 123–135. [Google Scholar]

- González-Fimbres, R. A., & Cuevas-Castro, C. S. (2022). Gender differences in the use of mobile exercise applications in Sport Training students. Revista de Ciencias del Ejercicio FOD, 17(1), 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Cabello, A., Ara, I., & Vicente-Rodríguez, G. (2018). Physical fitness and mortality: A review of epidemiological evidence. Sports Medicine, 48(5), 97–104. [Google Scholar]

- Grao-Cruces, A., Nuviala, A., Fernández-Martínez, A., & Porcel-Gálvez, A. M. (2022). Gender differences in health-related behaviors among adolescents: The role of social and psychological factors. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(4), 2210. [Google Scholar]

- Grao-Cruces, A., Nuviala, A., Fernández-Martínez, A., Porcel-Gálvez, A.-M., Moral-García, J.-E., & Martínez-López, E.-J. (2013). Adherence to the Mediterranean diet in rural and urban adolescents in southern Spain, life satisfaction, anthropometry, and physical and sedentary activities. Nutrición Hospitalaria, 28(4), 1129–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosso, G., Mateo, A., Rangelov, N., Buzeti, T., & Birt, C. (2020). Nutrition in the context of the sustainable development goals. European Journal of Public Health, 30(1), i19–i23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guthold, R., Stevens, G. A., Riley, L. M., & Bull, F. C. (2020). Global trends in insufficient physical activity among adolescents: A pooled analysis of 298 population-based surveys with 1·6 million participants. The Lancet. Child & Adolescent Health, 4(1), 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heredia-León, D. A., Valero-Valenzuela, A., Gómez-Mármol, A., & Manzano-Sánchez, D. (2023). Motivational profiles in physical education: Differences at the psychosocial, gender, age and extracurricular sports practice levels. Children, 10(1), 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernández, P., Guevara, R. M., Urchaga, J. D., & Moral, J. E. (2020). Self-perception of motivation in physical education classes according to sex, age and type of physical-sports practice. Papeles Salmantinos de Educación, 24, 149–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera-Ramos, E., Tomaino, L., Sánchez-Villegas, A., Ribas-Barba, L., Gómez, S. F., Wärnberg, J., Osés, M., González-Gross, M., Gusi, N., Aznar, S., Marín-Cascales, E., González-Valeiro, M. Á., Terrados, N., Tur, J. A., Segú, M., Fitó, M., Homs, C., Benavente-Marín, J. C., Labayen, I., … Serra-Majem, L. (2023). Trends in adherence to the Mediterranean diet in Spanish children and adolescents across two decades. Nutrients, 15(10), 2348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez, R., Gargallo, E., Dalmau, J. M., & Arriscado, D. (2022). Factors associated with a low level of physical activity in adolescents in La Rioja (Spain). Anales de Pediatría, 96(4), 326–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Boraita, J., Martínez-Vizcaíno, V., & Sánchez-López, M. (2022). Relationship between physical fitness and obesity in school-aged children: A longitudinal study. Journal of Pediatric Research, 89(3), 245–255. [Google Scholar]

- Langford, R., Bonell, C. P., Jones, H. E., Pouliou, T., Murphy, S. M., Waters, E., Komro, K. A., Gibbs, L. F., Magnus, D., & Campbell, R. (2017). The WHO Health Promoting School framework for improving the health and well-being of students and their academic achievement. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 1(4), CD008958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Bermudez, E., Gomez-Baya, D., Planells, E., & Molina-Lopez, J. (2024). The mediational role of positive youth development in the relationship between physical activity and health-related quality of life in adolescents from urban and rural environments. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 29(1), 2354917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, P. G., Gisladóttir, T., & Ries, F. (2020). Adherence to the Mediterranean diet, motives for physical exercise and body composition in Icelandic adolescents. Challenges: New Trends in Physical Education, Sport and Recreation, 83, 552–559. [Google Scholar]

- López-Gajardo, M. A., Leo, F. M., Sánchez-Miguel, P. A., López-Gajardo, D., Soulas, C., & Tapia-Serrano, M. A. (2022). KIDMED 2.0, An update of the KIDMED questionnaire: Evaluation of the psychometric properties in youth. Frontiers in Nutrition, 9, 945721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Sánchez, G., Ahmed, M. D., & Díaz-Suárez, A. (2017). Level of habitual physical activity in 13-year-old schoolchildren in Spain and India. A cross-cultural study. SPORT TK-Revista EuroAmericana de Ciencias del Deporte, 6(1), 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldonado, I. E. (2023). Sedentary lifestyles and benefits of physical activity in adolescents: A systematic review. MENTOR Revista de Investigación Educativa y Deportiva, 2(5), 315–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, J. S. (2022). Physical activity and psychological adjustment in university students. Journal of Applied Psychology, 10(1), 160–170. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Gómez, D., Sequí-Domínguez, I., Romero-Blanco, C., Rodríguez-Almagro, J., & Gómez-Salgado, J. (2022). Factores asociados a un bajo nivel de actividad física en adolescentes escolarizados en La Rioja (España). Anales de Pediatría, 97(2), 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateo-Orcajada, A., Abenza-Cano, L., & Vaquero-Cristóbal, R. (2024). Importance of perceived quality and usability of step tracker mobile apps for their use by adolescents. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 29(1), 2389310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayor-Díez, I., Sanchis-Soler, G., & Ávalos-Ramos, M. A. (2024). Gender and age differences in motivation towards Physical Education in Primary Education in Spanish students. Retos, 61, 971–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClanahan, R., & Weismuller, P. C. (2015). School nurses and care coordination for children with complex needs: An integrative review. The Journal of School Nursing: The Official Publication of the National Association of School Nurses, 31(1), 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melguizo-Ibáñez, E., Puertas-Molero, P., González-Valero, G., & Alonso-Vargas, J. M. (2022). An explanatory model of sport motivation, physical self-concept and anxiety as a function of the degree of adherence to the Mediterranean diet in future physical education teachers. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(20), 13547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melis, A., Anastasia, A., Zannoner, A., Salussolia, A., De Dominicis, F., Arrichiello, F., Ferretti, F., Marini, S., Masini, A., & Dallolio, L. (2021). Association between parents’ education level and KIDMED index: A cross-sectional study. European Journal of Public Health, 31(3), ckab164.218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, C. A., Cannon, G., Levy, R. B., Moubarac, J. C., Louzada, M. L., Rauber, F., Khandpur, N., Cediel, G., Neri, D., Martinez-Steele, E., Baraldi, L. G., & Jaime, P. C. (2019). Ultra-processed foods: What they are and how to identify them. Public Health Nutrition, 22(5), 936–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moral-García, J. E., Agraso-López, A. D., Pérez-Soto, J. J., Rosa-Guillamón, A., Tárraga-Marcos, M. L., García-Cantó, E., & Tárraga-López, P. J. (2019). Physical activity practice according to adherence to the Mediterranean diet, alcohol consumption and motivation in adolescents. Nutrición Hospitalaria, 36(2), 420–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Association of School Nurses (NASN). (2020). The role of the school nurse in providing school health services. Journal of School Nursing, 36(1), 6–8. [Google Scholar]

- Navarro-González, I., López-Nicolás, R., Rodríguez-Tadeo, A., Ros-Berruezo, G., Martínez-Marín, M., & Doménech-Asensi, G. (2016). Adherence to the Mediterranean diet by nursing students of Murcia (Spain). Nutricion Hospitalaria, 30(1), 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, F. B., Ruiz, J. R., & Castillo, M. J. (2013a). Physical activity, physical fitness and overweight in children and adolescents: Evidence from epidemiological studies. Endocrinology and Nutrition: Organ of the Spanish Society of Endocrinology and Nutrition, 60(8), 458–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, F. B., Ruiz, J. R., & Sjöström, M. (2013b). Physical activity, overweight and central adiposity in Swedish children and adolescents: The European youth heart study. International Journal of Behavioural Nutrition and Physical Activity, 4(1), 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra-Escartín, B., & Villalobos, F. (2020). Assessment of dietary habits and physical activity levels in school adolescents: A cross-sectional study. Revista Española de Nutrición Humana y Dietética, 24(4), 357–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peláez-Barrios, E. M., Aznar, A., Salas, A., & Vernetta, M. (2022). Relationship between physical condition and quality of life in adolescents aged 14 to 18 years. ESHPA-Education, Sport, Health and Physical Activity, 6(3), 294–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prochaska, J. J., Sallis, J. F., & Long, B. (2001). A physical activity screening measure for use with adolescents in primary care. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 155(5), 554–559. [Google Scholar]

- Quinde-Zambrano, L. F., Heredia-Arias, G. J., & Correa-Burgos, J. A. (2024). Physical activity levels in university students: Gender analysis. Portal de la Ciencia, 5(2), 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebollo-Ramos, M., Velázquez-Díaz, D., Corral-Pérez, J., Barany-Ruiz, A., Pérez-Bey, A., Fernández-Ponce, C., García-Cózar, F. J., Ponce-González, J. G., & Cuenca-García, M. (2020). Aerobic fitness, Mediterranean diet and cardiometabolic risk factors in adults. Aerobic fitness, Mediterranean diet and cardiometabolic risk in adults. Endocrinology, Diabetes and Nutrition, 67(2), 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Torres, Á.-F., Marín-Marín, J.-A., López-Belmonte, J., & Pozo-Sánchez, S. (2024). Analysis of physical activity and nutrition in students from Ecuador and the influence of family and institutional support. Retos, 54, 279–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Román, F., Ponce de León, C., & Ruiz-Juan, F. (2018). Motivations for physical activity practice in adults and its relationship with subjective well-being. International Journal of Medicine and Physical Activity and Sport Sciences, 18(69), 149–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggiero, E., Esposito, S., Costanzo, S., Di Castelnuovo, A., Cerletti, C., Donati, M. B., de Gaetano, G., Iacoviello, L., Bonaccio, M., & INHES Study Investigators. (2021). Ultra-processed food consumption and its correlates among Italian children, adolescents and adults from the Italian Nutrition & Health Survey (INHES) cohort study. Public Health Nutrition, 24(18), 6258–6271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, J. R., Castro-Pinero, J., Artero, E. G., Ortega, F. B., Sjostrom, M., Suni, J., & Castillo, M. J. (2009a). Predictive validity of health-related fitness in youth: A systematic review. British Journal Sports Medicine, 43(12), 909–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz, J. R., Ortega, F. B., Martínez-Gómez, D., Labayen, I., Moreno, L. A., De Bourdeaudhuij, I., Manios, Y., González-Gross, M., Mauro, B., Molnar, D., Gottrand, F., Widhalm, K., Kafatos, A., Zaccaria, M., & Sjöström, M. (2009b). Objectively measured physical activity and sedentary time in European adolescents: The HELENA study. American Journal of Epidemiology, 169(2), 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development and wellbeing. The American Psychologist, 55, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallis, J. F., Owen, N., & Fisher, E. B. (2020). Ecological models of health behavior. In K. Glanz, B. K. Rimer, & K. Viswanath (Eds.), Health behavior: Theory, research, and practice (5th ed., pp. 43–64). Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Oliva, D., Leo, F. M., Amado, D., González-Ponce, I., & García-Calvo, T. (2012). Desarrollo de un cuestionario para valorar la motivación en educación física. Revista Iberoamericana de Psicología del Ejercicio y el Deporte, 1(1), 20–32. [Google Scholar]

- Serra-Majem, L., Ribas, L., Ngo, J., Ortega, R. M., García, A., & Pérez-Rodrigo, C. (2004). Food, youth and the Mediterranean diet in Spain. Development of KIDMED, Mediterranean diet quality index in children and adolescents. Public Health Nutrition, 7(7), 931–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano, J., Pizarro, A. P., Casterad, J. Z., Álvarez, F. D., & García-González, L. (2017). Perceived barriers to physical activity practice in university students. Differences by gender and physical activity levels. Universitas Psicológica, 16, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Suárez-Manzano, S., Solas-Martínez, J. L., Loureiro, V., & Rusillo-Magdaleno, A. (2023). Physical activity is associated with better mathematical calculation, linguistic reasoning, behaviour and attention in ADHD girls. Retos, 51, 1388–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Q., Jiang, C., Wang, M., Huang, Y., Wang, J., Du, Z., & Zhang, N. (2024). Implicit theories of health predict engagement in healthy lifestyles among Chinese early adolescents: The mediating effect of future self-continuity. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 29(1), 2409428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, D. S., Rodrigues, F., Cid, L., & Monteiro, D. (2022). Enjoyment as a predictor of exercise habit, intention to continue exercising, and exercise frequency: The intensity traits discrepancy moderation role. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 780059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teixeira, P. J., Carraça, E. V., Markland, D., Silva, M. N., & Ryan, R. M. (2012). Exercise, physical activity, and self-determination theory: A systematic review. The International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 9, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tremblay, M. S., Aubert, S., Barnes, J. D., Saunders, T. J., Carson, V., Latimer-Cheung, A. E., Chastin, S. F. M., Altenburg, T. M., Chinapaw, M. J. M., & SBRN Terminology Consensus Project Participants. (2017). Sedentary behavior research network (SBRN)—Terminology consensus project process and outcome. The International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 14(1), 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trigueros, R., Mínguez, L. A., González-Bernal, J. J., Aguilar-Parra, J. M., Soto-Cámara, R., Álvarez, J. F., & Rocamora, P. (2020). Physical education classes as a precursor to the mediterranean diet and the practice of physical activity. Nutrients, 12(1), 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasconcellos, D., Parker, P. D., Hilland, T., Cinelli, R., Owen, K. B., Kapsal, N., Lee, J., Antczak, D., Ntoumanis, N., Ryan, R. M., & Lonsdale, C. (2020). Self-determination theory applied to physical education: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Educational Psychology, 112(7), 1444–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vera-Lara, S., & Esteves-Fajardo, Z. (2023). Importance of nutrition at an early age and its improvement in sports performance. Cienciamatria, 9(1), 333–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2020). WHO guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. World Health Organization. ISBN 978-92-4-001481-7. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2021). Obesity and overweight. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight (accessed on 4 March 2025).

- World Medical Association (WMA). (1964). Declaration of Helsinki—Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects (last updated 2013). Available online: https://www.wma.net (accessed on 4 March 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).