Seeing Through Other Eyes: How Language Experience and Cognitive Abilities Shape Theory of Mind

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Contemporary Research on Adult Theory of Mind

2.1. The Relationship Between Bilingualism and Theory of Mind

2.2. Individual Differences Approaches to Bilingualism and Theory of Mind

2.3. Current Study

3. Method

3.1. Design and Participants

Participant Language and Background

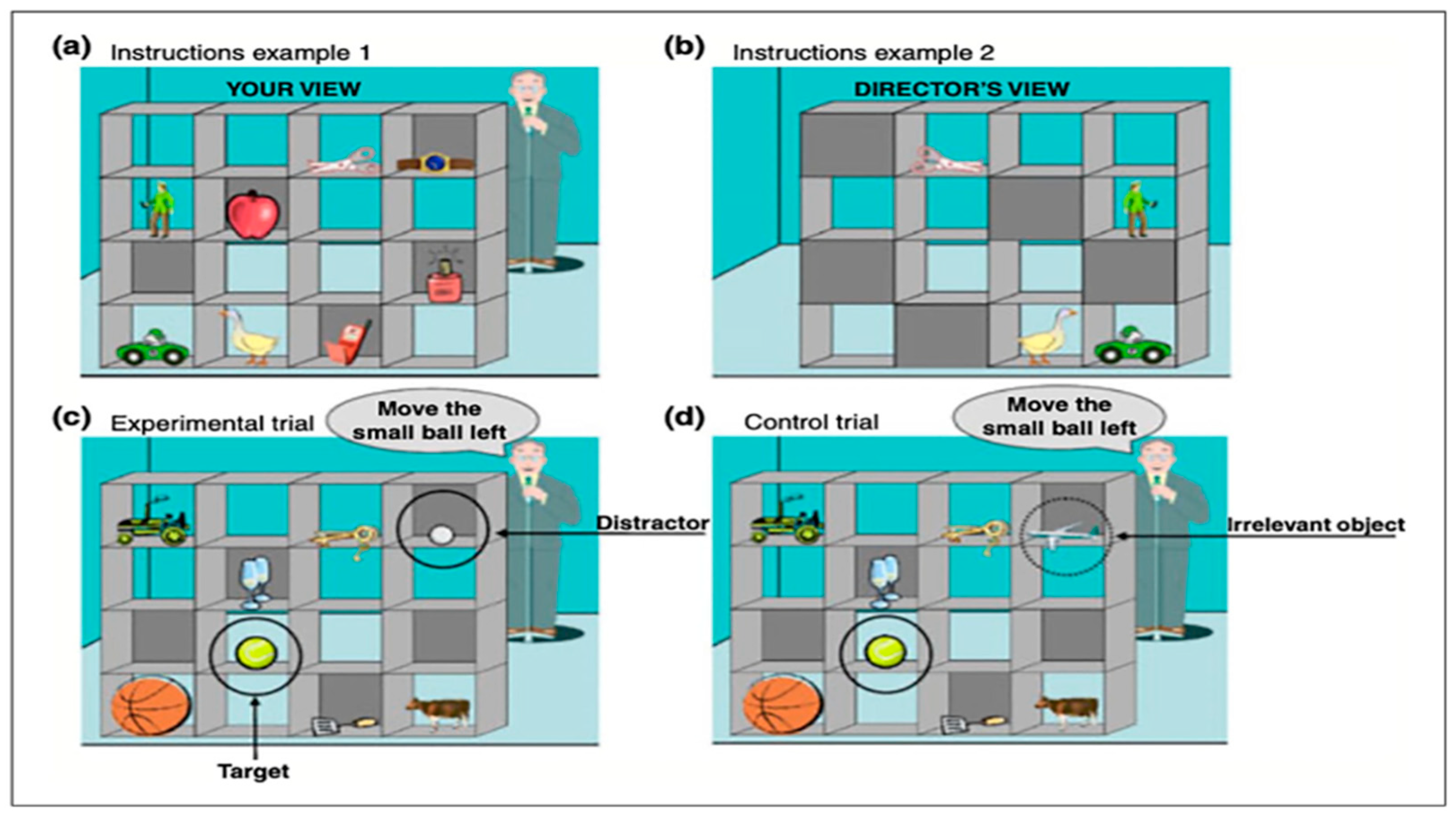

3.2. Measurements

3.3. Procedure

4. Results

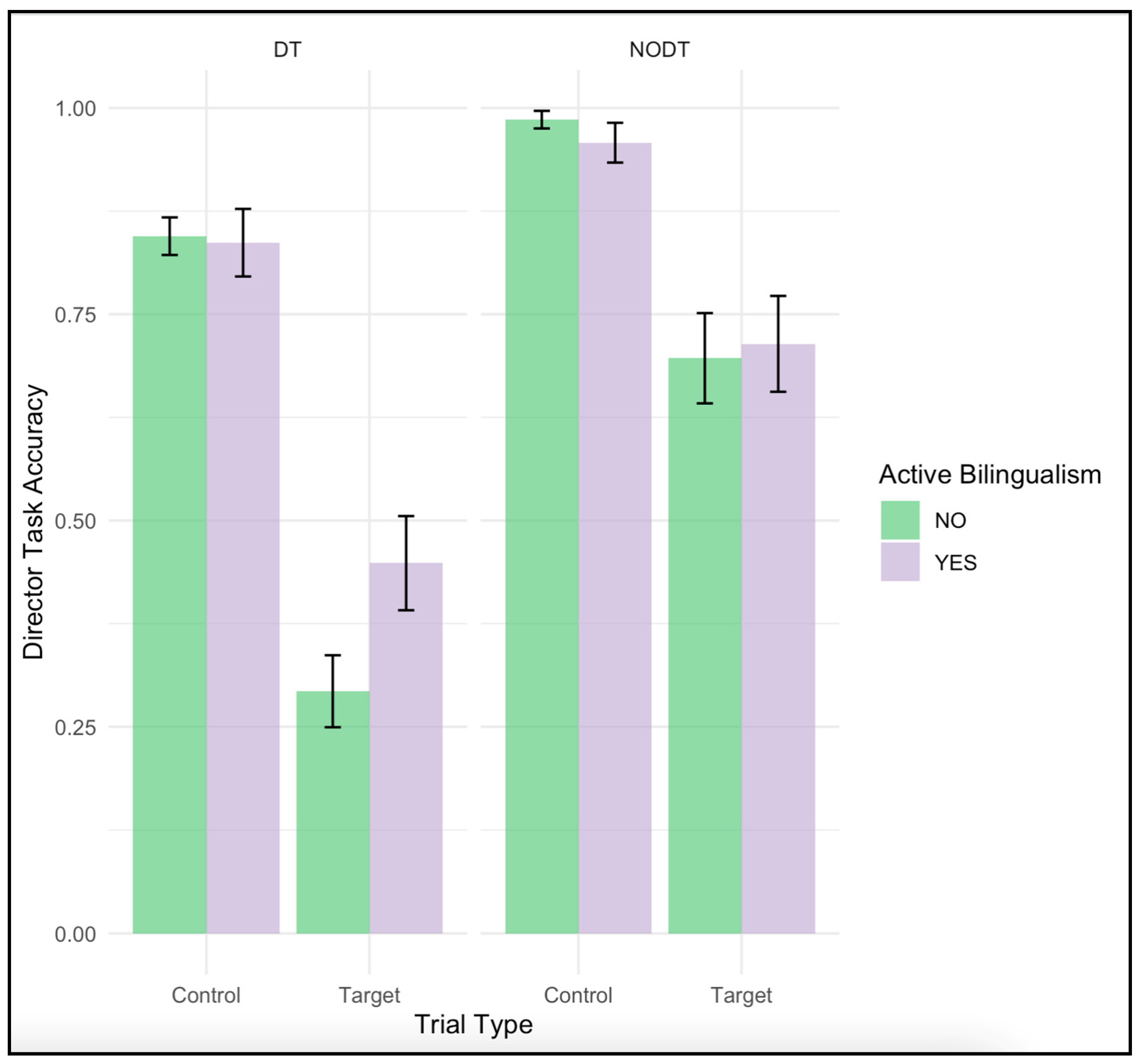

5. Main Analysis

5.1. ToM and Bilingualism

5.2. ToM, Bilingualism and Gf

6. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Although the total sample included 250 participants, only 88 were able to complete the Director Task due to technological errors. Of those, 66 participants met inclusion criteria for the bilingualism analysis based on language background data and proficiency cutoffs. |

| 2 | Reaction times were also analyzed; as expected, there were no meaningful differences in performance across groups or conditions, replicating previous findings. |

| 3 | A post-hoc power analysis using G*Power estimated the analysis possessed 67% power to detect a small-to-medium three-way interaction (f = 0.15) in a 2 × 2 mixed factorial design. This suggests that the non-significant interaction observed in our results may reflect a Type II error due to limited statistical power. |

| 4 | Monolinguals reported higher L1 proficiency than bilinguals across speaking (t(64) = 2.85, p = 0.006), comprehension (t(64) = 2.61, p = 0.012), and reading (t(64) = 1.98, p = 0.053). |

References

- Apperly, I. (2010). Mindreaders: The cognitive basis of “theory of mind”. Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Apperly, I. A., & Butterfill, S. A. (2009). Do humans have two systems to track beliefs and belief-like states? Psychological Review, 116(4), 953–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apperly, I. A., Carroll, D. J., Samson, D., Humphreys, G. W., Qureshi, A., & Moffitt, G. (2010). Why are there limits on theory of mind use? Evidence from adults’ ability to follow instructions from an ignorant speaker. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 63(6), 1201–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apperly, I. A., Samson, D., & Humphreys, G. W. (2008). Domain-specificity and theory of mind: Evaluating neuropsychological evidence. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 12(8), 301–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astington, J. W., & Baird, J. A. (Eds.). (2005). Why language matters for theory of mind. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey, P. E., & Henry, J. D. (2008). Growing less empathic with age: Disinhibition of the self-perspective. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 63(4), P219–P226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron-Cohen, S., Leslie, A. M., & Frith, U. (1985). Does the autistic child have a “theory of mind”? Cognition, 21(1), 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bialystok, E. (2009). Bilingualism: The good, the bad, and the indifferent. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 12, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bialystok, E., & Craik, F. I. (2010). Cognitive and linguistic processing in the bilingual mind. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 19(1), 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bialystok, E., & Senman, L. (2004). Executive processes in appearance–reality tasks: The role of inhibition of attention and symbolic representation. Child Development, 75, 562–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bice, K., & Kroll, J. F. (2019). English only? Monolinguals in linguistically diverse contexts have an edge in language learning. Brain and Language, 196, 104644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birch, S. A. J., & Bloom, P. (2007). The curse of knowledge in reasoning about false beliefs. Psychological Science, 18(5), 382–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blakemore, S. J. (2008). The social brain in adolescence. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 9, 267–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burgoyne, A. P., Tsukahara, J. S., Mashburn, C. A., Pak, R., & Engle, R. W. (2023). Nature and measurement of attention control. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 152(8), 2369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, S. M., & Moses, L. J. (2001). Individual differences in inhibitory control and children’s theory of mind. Child Development, 72(4), 1032–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carpenter, M., Call, J., & Tomasello, M. (2002). A new false belief test for 36-month-olds. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 20(3), 393–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, P. A., Just, M. A., & Shell, P. (1990). What one intelligence test measures: A theoretical account of the processing in the Raven Progressive Matrices Test. Psychological Review, 97(3), 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carstensen, L. L., Fung, H. H., & Charles, S. T. (2003). Socioemotional selectivity theory and the regulation of emotion in the second half of life. Motivation and Emotion, 27, 103–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattell, R. B. (1963). Theory of fluid and crystallized intelligence: A critical experiment. Journal of Educational Psychology, 54, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chierchia, G., Fuhrmann, D., Knoll, L. J., Pi-Sunyer, B. P., Sakhardande, A. L., & Blakemore, S. J. (2019). The matrix reasoning item bank (MaRs-IB): Novel, open-access abstract reasoning items for adolescents and adults. Royal Society Open Science, 6(10), 190232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutting, A. L., & Dunn, J. (1999). Theory of mind, emotion understanding, language, and family background: Individual differences and interrelations. Child Development, 70(4), 853–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLuca, V., Romero Lauro, L. J., & Bialystok, E. (2019). Bilingualism as a desirable difficulty: Advantages in word learning depend on regulation of the dominant language. Neuropsychologia, 133, 107172. [Google Scholar]

- Devine, R. T., & Hughes, C. (2014). Relations between false belief understanding and executive function in early childhood: A meta-analysis. Child Development, 85(5), 1777–1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diaz, R. M., & Farrar, M. J. (2017). The effects of language switching on theory of mind in bilingual children. International Journal of Bilingualism, 21(2), 193–207. [Google Scholar]

- Dumontheil, I., Apperly, I. A., & Blakemore, S. J. (2010). Online usage of theory of mind continues to develop in late adolescence. Developmental Science, 13(2), 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J., Cho, S., & Luk, G. (2023). Assessing Theory of Mind in bilinguals: A scoping review on tasks and study designs. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 27(4), 531–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, H. J., & Cane, J. E. (2017). Tracking the real-time processing of false beliefs using eye movements. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 70(3), 573–593. [Google Scholar]

- Flavell, J. H., Everett, B. A., Croft, K., & Flavell, E. R. (1981). Young children’s knowledge about visual perception: Further evidence for the Level 1–Level 2 distinction. Developmental Psychology, 17(1), 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasser, M. (2000). Bilingual lexicon: Implications for theories of cross-language transfer. Applied Psycholinguistics, 21, 115–130. [Google Scholar]

- Genesee, F., Paradis, J., & Crago, M. B. (1996). Dual language development and disorders: A handbook on bilingualism and second language learning. Brookes. [Google Scholar]

- German, T. P., & Hehman, J. A. (2006). Representational and executive selection resources in ‘theory of mind’: Evidence from compromised belief-desire reasoning in old age. Cognition, 101(1), 129–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giedd, J. N., Blumenthal, J., Jeffries, N. O., Castellanos, F. X., Liu, H., Zijdenbos, A., Paus, T., Evans, A. C., & Rapoport, J. L. (1999). Brain development during childhood and adolescence: A longitudinal MRI study. Nature Neuroscience, 2(10), 861–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goetz, P. J. (2003). The effects of bilingualism on theory of mind development. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 6(1), 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gollan, T. H., Weissberger, G. H., Runnqvist, E., Montoya, R. I., & Cera, C. M. (2012). Self-ratings of spoken language dominance: A multilingual naming test. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 15(3), 594–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goring, S., & Navarro, E. (in press). Lifespan perspective of theory of mind, fluid intelligence, and crystallized intelligence: After young adulthood. Aging, Neuropsychology and Cognition. [Google Scholar]

- Grainger, S. A., Henry, J. D., Alister, M., Bourdaniotis, X. E., Mead, J., Bailey, T. G., Coombes, J. S., & Vear, N. (2023). Cardiorespiratory Fitness and muscular strength do not predict Social Cognitive Capacity in Older Age. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 78(11), 1824–1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, D. W., & Abutalebi, J. (2013). Language control in bilinguals: The adaptive control hypothesis. Journal of Cognitive Psychology, 25(5), 515–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, D. M., Bellana, B., & Bialystok, E. (2013). Perspective-taking ability in bilingual children: Exploring the effects of language and culture. Developmental Science, 16(6), 815–826. [Google Scholar]

- Hambrick, D. Z., & Engle, R. W. (2003). The role of working memory in problem solving. In The psychology of problem solving (pp. 176–206). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hartanto, A., & Yang, H. (2020). Bilingualism and executive functions: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 146(4), 388–427. [Google Scholar]

- Henry, J. D., Phillips, L. H., Ruffman, T., & Bailey, P. E. (2013). A meta-analytic review of age differences in theory of mind. Psychology and Aging, 28(3), 826–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huepe, D., Roca, M., Salas, N., Canales-Johnson, A., Rivera-Rei, A. A., Zamorano, L., Concepción, A., Manes, F., & Ibañez, A. (2011). Fluid intelligence and psychosocial outcome: From logical problem-solving to social adaptation. PLoS ONE, 6(9), e24858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, C., & Russell, J. (1993). Autistic children’s difficulty with mental disengagement from an object: Evidence for a deficit in executive function. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 34(3), 437–455. [Google Scholar]

- Jaccard, J., & Cividin, M. (2001). Structural equation modeling for theory of mind research. Psychological Methods, 6(1), 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Keysar, B., Lin, S., & Barr, D. J. (2003). Limits on theory of mind use in adults. Cognition, 89(1), 25–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitayama, S., King, A., Yoon, C., Tompson, S., Huff, S., & Liberzon, I. (2014). The dopamine D4 receptor gene (DRD4) moderates cultural difference in independent versus interdependent social orientation. Psychological Science, 25(6), 1169–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kloo, D., & Perner, J. (2003). Training transfer between card sorting and false belief understanding: Helping children apply conflicting descriptions. Child Development, 74(6), 1823–1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kovács, Á. M. (2009). Early bilingualism enhances mechanisms of false-belief reasoning. Developmental Science, 12(1), 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kupisch, T., & Rothman, J. (2018). Terminology matters! Why difference is not incompleteness and how early child bilinguals are heritage speakers. International Journal of Bilingualism, 22(5), 564–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leslie, A. (1994). ToMM, ToBy, and Agency: Core architecture and domain specificity. In L. A. Hirschfeld, & S. A. Gelman (Eds.), Mapping the mind: Domain specificity in cognition and culture (pp. 119–148). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Leslie, A. M., German, T. P., & Polizzi, P. (2005). Belief-desire reasoning as a process of selection. Cognitive Psychology, 50(1), 45–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luk, G., & Bialystok, E. (2013). Bilingualism is not a categorical variable: Interaction between language proficiency and usage. Journal of Cognitive Psychology, 25(5), 605–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marian, V., Blumenfeld, H. K., & Kaushanskaya, M. (2007). The language experience and proficiency questionnaire (LEAP-Q): Assessing language profiles in bilinguals. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 50(4), 940–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mier, D., Lis, S., Neuthe, K., Sauer, C., Esslinger, C., Gallhofer, B., & Kirsch, P. (2010). The involvement of emotion recognition in affective theory of mind. Psychophysiology, 47(6), 1028–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milligan, K., Astington, J. W., & Dack, L. A. (2007). Language and theory of mind: Meta-analysis of the relation between language ability and false-belief understanding. Child Development, 78(2), 622–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, P., Robinson, E. J., Isaacs, J. E., & Nye, R. (2009). When children judge false beliefs to be true: Individual differences and neuropsychological correlates. Child Development, 80(2), 441–460. [Google Scholar]

- Navarro, E. (2022). What is theory of mind? A psychometric study of theory of mind and intelligence. Cognitive Psychology, 136, 101495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, E., & Conway, L. (2021). Adult bilinguals outperform monolinguals in theory of mind. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 74(11), 1841–1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navarro, E., DeLuca, V., & Rossi, E. (2022). It takes a village: Using network science to identify the effect of individual differences in bilingual experience for theory of mind. Brain Sciences, 12(4), 487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, E., Macnamara, B. N., Glucksberg, S., & Conway, A. R. (2020). What influences successful communication? An examination of cognitive load and individual differences. Discourse Processes, 57(10), 880–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, E., & Rossi, E. (2023). Using latent variable analysis to capture individual differences in bilingual language experience. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 27(4), 700–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, E., & Rossi, E. (2024). Inhibitory control partially mediates the relationship between metalinguistic awareness and perspective-taking. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research, 53, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nichols, E. S., Wild, C. J., Stojanoski, B., Battista, M. E., & Owen, A. M. (2020). Bilingualism affords no general cognitive advantages: A population study of executive function in 11,000 people. Psychological Science, 31(5), 548–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olson, D. J. (2024). Bilingual language dominance and code-switching patterns. Heritage Language Journal, 21(1), 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paap, K. R., Majoubi, J., Anders-Jefferson, R. T., Iosilevsky, R., & Tate, C. U. (2025). Do bilingual advantages in domain-general executive functioning occur in everyday life and/or when performance-based measures have excellent psychometric properties? Psychological Review. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perner, J. (1988). Developing semantics for theories of mind: From propositional attitudes to mental representation. In J. W. Astington, P. L. Harris, & D. R. Olson (Eds.), Developing theories of mind (pp. 141–172). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pile, V., Haller, S. P., Hiu, C. F., & Lau, J. Y. (2017). Young people with higher social anxiety are less likely to adopt the perspective of another: Data from the director task. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 55, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quesque, F., & Rossetti, Y. (2020). What do theory-of-mind tasks actually measure? Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 24(4), 248–249. [Google Scholar]

- Qureshi, A. W., Apperly, I. A., & Samson, D. (2010). Executive function is necessary for perspective selection, not Level-1 visual perspective calculation: Evidence from a dual-task study of adults. Cognition, 117(2), 230–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raimo, S., Cropano, M., Roldán-Tapia, M. D., Ammendola, L., Malangone, D., & Santangelo, G. (2022). Cognitive and affective theory of mind across adulthood. Brain Sciences, 12(7), 899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raven, J. (2000). The Raven’s progressive matrices: Change and stability over culture and time. Cognitive Psychology, 41(1), 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raven, J. C. (1938). Progressive Matrices: A perceptual test of Intelligence. H.K. Lewis. [Google Scholar]

- Roca, M., Parr, A., Thompson, R., Woolgar, A., Torralva, T., Antoun, N., Manes, F., & Duncan, J. (2010). Executive function and fluid intelligence after frontal lobe lesions. Brain, 133(Pt 1), 234–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio-Fernandez, P. (2017). The director task: A test of Theory-of-Mind use or selective attention? Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 24(4), 1121–1128. [Google Scholar]

- Rubio-Fernandez, P., & Glucksberg, S. (2012). Reasoning about beliefs and desires: A developmental perspective. Cognitive Psychology, 64(1–2), 74–96. [Google Scholar]

- Samuel, S., Roehr-Brackin, K., Jelbert, S., & Clayton, N. S. (2019). Flexible egocentricity: Asymmetric switch costs on a perspective-taking task. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 45(2), 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholl, B. J., & Leslie, A. M. (2001). Minds, modules, and meta-analysis. Child Development, 72, 696–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, S. R. (2018). Do bilinguals have an advantage in theory of mind? A meta-analysis. Frontiers in Communication, 3, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, P., Kabani, N. J., Lerch, J. P., Eckstrand, K., Lenroot, R., Gogtay, N., Greenstein, D., Clasen, L., Evans, A., Rapoport, J. L., & Giedd, J. N. (2008). Neurodevelopmental trajectories of the human cerebral cortex. Journal of Neuroscience, 28(14), 3586–3594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singelis, T. M. (1994). The measurement of independent and interdependent self-construals. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 20(5), 580–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sperber, D. (2000). Metarepresentations in an evolutionary perspective. Metarepresentations: A Multidisciplinary Perspective, 10, 117–137. [Google Scholar]

- Sperber, D., & Wilson, D. (1995). Relevance: Communication and cognition. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Surrain, S., & Luk, G. (2019). Describing bilinguals: A systematic review of labels and descriptions used in the literature between 2005–2015. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 22(2), 401–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titone, D. A., & Tiv, M. (2023). Rethinking multilingual experience through a Systems Framework of Bilingualism. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 26(1), 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiv, M., Kutlu, E., O’Regan, E., & Titone, D. (2022). Bridging people and perspectives: General and language-specific social network structure predict mentalizing across diverse sociolinguistic contexts. Canadian Journal of Experimental Psychology/Revue Canadienne de Psychologie Expérimentale, 76(4), 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiv, M., O’Regan, E., & Titone, D. (2023). The role of mentalizing capacity and ecological language diversity on irony comprehension in bilingual adults. Memory & Cognition, 51, 253–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdez, G., & Figueora, R. A. (1994). Bilingual and testing: A special case of bias. Ablex Publishing Corp. [Google Scholar]

- Warnell, K. R., & Redcay, E. (2019). Minimal coherence among varied theory of mind measures in childhood and adulthood. Cognitive Development, 50, 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wellman, H. M. (1990). The child’s theory of mind. MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wellman, H. M. (2018). Theory of mind: The state of the art. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 15(6), 728–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilhelm, O., Herzmann, G., Kunina, O., Danthiir, V., Schacht, A., & Sommer, W. (2010). Individual differences in perceiving and recognizing faces—One element of social cognition. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 99(3), 530–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S., & Keysar, B. (2007). The effect of culture on perspective taking. Psychological Science, 18(7), 600–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeh, Z. T. (2013). Role of theory of mind and executive function in explaining social intelligence: A structural equation modeling approach. Aging & Mental Health, 17(5), 527–534. [Google Scholar]

| Varibales | M | SD |

| Age | 20 | 3.09 |

| L1 AoA | 2.47 | 2.26 |

| L2 AoA | 3.67 | 3.57 |

| Self-reported L1 and L2 frequency | ||

| L1 | L2 | |

| English | 79% | 18% |

| Spanish | 16% | 72% |

| Other | 4% | 9% |

| Self-reported Language Acquisition Pattern | ||

| Acquired First (A1) | Acquired Second (A2) | |

| English | 38% | 5% |

| Spanish | 53% | 32% |

| Other | 8% | 17% |

| Skill | L1 | L2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | |

| Comprehension | 8.52 | 1.93 | 7.12 | 2.32 |

| Speaking | 8.39 | 1.93 | 6.13 | 2.53 |

| Reading | 8.41 | 1.98 | 6.31 | 2.51 |

| Daily Exposure | 73.48 | 19.02 | 27.35 | 18.87 |

| Groups | Bilingual Group | Monolingual Group | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 27 | n = 39 | |||||||||

| M | SD | Min/Max | Skew | K | M | SD | Min/Max | Skew | K | |

| Director Condition | ||||||||||

| Target Trials | 0.45 | 0.3 | 0.12/1 | 0.63 | −0.98 | 0.29 | 0.27 | 0/0.88 | 0.67 | −0.87 |

| Control Trials | 0.84 | 0.21 | 0/1 | 2.22 | 5.99 | 0.84 | 0.14 | 0.33/1 | −1.18 | 2.17 |

| No Director Condition | ||||||||||

| Target Trials | 0.71 | 0.3 | 0.12/1 | −0.47 | −1.36 | 0.7 | 0.34 | 0/1 | −0.81 | −0.72 |

| Control Trials | 0.96 | 0.13 | 0.38/1 | −3.75 | 14.4 | 0.99 | 0.07 | 0.67/1.1 | −3.36 | 12.45 |

| Cognitive Measures | ||||||||||

| Fluid intelligence (Gf) | 0.44 | 0.07 | 0.30/0.56 | −0.18 | −0.95 | 0.43 | 0.07 | 0.27/0.55 | −0.57 | −0.38 |

| Attention Control (AC) | 0.97 | 0.4 | 0.32/1.70 | 0.34 | −1.07 | 0.87 | 0.33 | 0.20/1.46 | −0.14 | −1.04 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pathare, M.; Navarro, E.; Conway, A.R.A. Seeing Through Other Eyes: How Language Experience and Cognitive Abilities Shape Theory of Mind. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 755. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060755

Pathare M, Navarro E, Conway ARA. Seeing Through Other Eyes: How Language Experience and Cognitive Abilities Shape Theory of Mind. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(6):755. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060755

Chicago/Turabian StylePathare, Manali, Ester Navarro, and Andrew R. A. Conway. 2025. "Seeing Through Other Eyes: How Language Experience and Cognitive Abilities Shape Theory of Mind" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 6: 755. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060755

APA StylePathare, M., Navarro, E., & Conway, A. R. A. (2025). Seeing Through Other Eyes: How Language Experience and Cognitive Abilities Shape Theory of Mind. Behavioral Sciences, 15(6), 755. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060755