Compassion in Mexico and the United States: Unpacking Cultural Differences

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Cultural Differences in Compassion

1.2. The Case of Ecuador: Compassion Focusing on Both the Positive and the Negative

1.2.1. Valuing the Positive in Latin American Cultural Contexts

1.2.2. Accepting the Negative in Latin American Cultural Contexts

1.3. Unpacking Cultural Differences in Compassion: Avoided Negative Affect

1.4. Unpacking Cultural Differences in Compassion Even Further: Emotion Sharing

1.5. The Present Research: ANA, Emotion Sharing, and Compassionate Faces in Mexico

2. Method

2.1. Participants

2.2. Materials and Procedure

2.2.1. Reverse Correlation Task

2.2.2. Aggregating and Coding of the Individual Composite Images

2.2.3. Affect Valuation Index

2.2.4. Coding of Description of Most Compassionate Response: Emotion Sharing and Expressions of Love/Kindness

2.2.5. Demographics Questionnaire

3. Results

3.1. Do U.S. Americans Want to Avoid Feeling Negative More than Mexicans Do?

3.2. Do Compassionate Responses Consist of More Emotion Sharing for Mexicans Compared to for U.S. Americans?

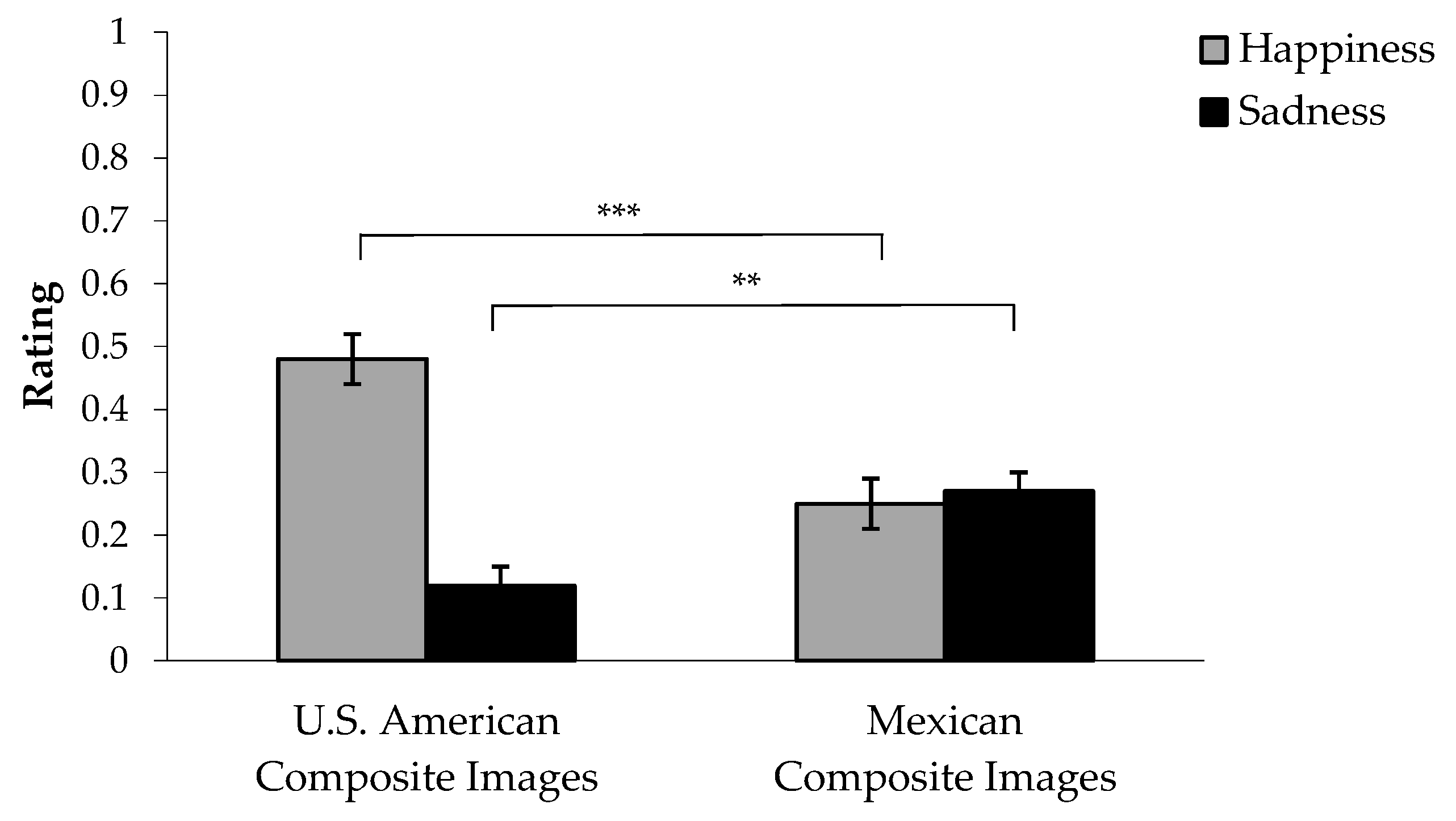

3.3. Do Mental Representations of a Compassionate Face Depict More Sadness and Less Happiness for Mexicans than for U.S. Americans?

3.4. Do ANA and Placing Importance on Emotion Sharing for Compassion Sequentially Mediate the Cultural Differences in Conceptualizations of a Compassionate Face?

4. Discussion

4.1. Cultural Differences in ANA

4.2. Cultural Differences in Emotion Sharing as Part of Compassionate Responses

4.3. Cultural Differences in What People Consider to Be a Compassionate Face

4.4. Sequential Mediation: ANA and Emotion Sharing Explain Cultural Differences in Amounts of Sadness in Conceptualizations of a Compassionate Face

4.5. Implications and Future Research

4.6. Limitations

4.7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | We used the same materials as did Larco et al. (2024). |

| 2 | While this confidence interval does not mathematically include zero, it includes a number that is close to zero. Caution should be used when interpreting indirect effects that just exclude zero (Götz et al., 2021). However, the present study replicates the findings reported in Larco et al. (2024). We were able to not only replicate the cultural differences in ANA, emotion sharing, and sadness and happiness depicted in compassionate faces, but also the indirect effect in this sequential mediation analysis. |

| 3 | We also examined the other indirect effects in the model. The indirect effect of ANA alone was not statistically significant. It was estimated to lie between −0.075 and 0.014 with 95% confidence interval using Hayes’ (2017) bootstrapping macro with 10,000 bootstrap samples. The indirect effect of emotion sharing alone was statistically significant. It was estimated to lie between −0.067 and −0.005 with 95% confidence interval. |

| 4 | We also examined the other indirect effects in the model. The indirect effect of ANA alone was not statistically significant. It was estimated to lie between −0.019 and 0.049 with 95% confidence interval. The indirect effect of emotion sharing alone was also not statistically significant. It was estimated to lie between −0.014 and 0.078 with 95% confidence interval. |

References

- Acevedo, A. M., Herrera, C., Shenhav, S., Yim, I. S., & Campos, B. (2020). Measurement of a Latino cultural value: The Simpatía scale. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 26(4), 419–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brainerd, C., Stein, L., Silveira, R., Rohenkohl, G., & Reyna, V. (2008). How does negative emotion cause false memories? Psychological Science, 19(9), 919–925. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Brinkman, L., Todorov, A., & Dotsch, R. (2017). Visualising mental representations: A primer on noise-based reverse correlation in social psychology. European Review of Social Psychology, 28(1), 333–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, B., & Kim, H. S. (2017). Incorporating the cultural diversity of family and close relationships into the study of health. American Psychologist, 72(6), 543–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canfield, J., Hansen, M. V., & Tabatsky, D. (2009). Chicken soup for the Soul: The cancer book: 101 stories of courage, support, and love. Chicken Soup for the Soul Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, J.-H., Detrick, S. M., Maas, Z., Coşkun, H., Klos, C., Zeifert, H., Parmer, E., & Sule, J. (2020). Cross-cultural comparison of compassion: An in-depth analysis of cultural differences in compassion using the Compassion of Others’ Lives (COOL) Scale. The Humanistic Psychologist, 49(3), 459–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chorpita, B. F., Albano, A. M., & Barlow, D. H. (1998). The structure of negative emotions in a clinical sample of children and adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 107(1), 74–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clair, J. (2005). Melancholie: Genie und Wahnsinn in der Kunst [Melancholy: Genius and madness in the arts]. Hatje Cantz. [Google Scholar]

- Condon, P., & Feldman Barrett, L. (2013). Conceptualizing and experiencing compassion. Emotion, 13(5), 817–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cone, J., Brown-Iannuzzi, J. L., Lei, R., & Dotsch, R. (2020). Type I error is inflated in the two-phase reverse correlation procedure. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 12(5), 760–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Matta, R. A. (1995). For an anthropology of the Brazilian tradition, or “A virtude está no meio”. In D. J. Hess, & R. A. Da Matta (Eds.), The Brazilian puzzle: Culture on the borderlands of the Western world (pp. 270–292). Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Delgado, A. R., Prieto, G., & Burin, D. I. (2020). Agreement on emotion labels’ frequency in eight Spanish linguistic areas. PLoS ONE, 15(8), e0237722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, S., & Nisbett, R. E. (2017). Beyond East and West: Cognitive style in Latin America. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 48(10), 1554–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dotsch, R. (2016). rcicr: Reverse-correlation image-classification toolbox (R package version 0.3.4.1) [Computer software]. Available online: https://ron.dotsch.org/rcicr (accessed on 21 May 2025).

- Dotsch, R., & Todorov, A. (2012). Reverse correlating social face perception. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 3(5), 562–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrenreich, B. (2009). Bright-sided: How the relentless promotion of positive thinking has undermined America. Metropolitan Books. [Google Scholar]

- Falconer, C. J., Lobmaier, J. S., Christoforou, M., Kamboj, S. K., King, J. A., Gilbert, P., & Brewin, C. R. (2019). Compassionate faces: Evidence for distinctive facial expressions associated with specific prosocial motivations. PLoS ONE, 14(1), e0210283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fonseca, R. G., Marques, P. I. S., da Costa, F. F., Landeira-Fernandez, J., Rimes, K. A., & Mograbi, D. C. (2023). Cross-cultural differences in beliefs about emotions: A comparison between Brazilian and British participants. Jornal Brasileiro de Psiquiatria, 72(3), 152–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forgas, J. P. (2008). Affect and cognition. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 3(2), 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frasure-Smith, N., Lesperance, F., & Talajic, M. (1995). The impact of negative emotions on prognosis following myocardial infarction: Is it more than depression? Health Psychology, 14(5), 388–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelfert, H.-D. (2005). Was ist deutsch? Wie die Deutschen wurden, was sie sind [What is German? How the Germans became the way they are]. C. H. Beck Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Goetz, J. L., Keltner, D., & Simon-Thomas, E. (2010). Compassion: An evolutionary analysis and empirical review. Psychological Bulletin, 136(3), 351–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Górriz, A. B., Etchezahar, E., Pinilla-Rodríguez, D. E., Giménez-Espert, M. D. C., & Prado-Gascó, V. (2021a). Cross-cultural validation of the Mood Questionnaire in three Spanish-speaking countries Argentina, Ecuador, and Spain. The Journal of Social Psychology, 161(2), 216–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Górriz, A. B., Etchezahar, E., Pinilla-Rodríguez, D. E., Giménez-Espert, M. D. C., & Soto-Rubio, A. (2021b). Validation of TMMS-24 in three Spanish-speaking countries: Argentina, Ecuador, and Spain. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(18), 9753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Götz, M., O’Boyle, E. H., Gonzalez-Mulé, E., Banks, G. C., & Bollmann, S. S. (2021). The “Goldilocks Zone”: (Too) many confidence intervals in tests of mediation just exclude zero. Psychological Bulletin, 147(1), 95–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, J. J., & Levenson, R. W. (1997). Hiding feelings: The acute effects of inhibiting negative and positive emotion. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 106, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A. F. (2017). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Hedderich, N. (1999). When cultures clash: Views from the professions. Die Unterrichtspraxis/Teaching German, 32, 158–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Held, B. S., & Bohart, A. C. (2002). Introduction: The (overlooked) virtues of “unvirtuous” attitudes and behavior: Reconsidering negativity, complaining, pessimism, and “false” hope. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 58(9), 961–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henrich, J., Heine, S., & Norenzayan, A. (2010). Most people are not WEIRD. Nature, 466, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holloway, R. A., Waldrip, A. M., & Ickes, W. (2009). Evidence that a simpático self-schema accounts for differences in the self-concepts and social behavior of Latinos versus Whites (and Blacks). Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 96(5), 1012–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keltner, D. (2009). Born to be good: The science of a meaningful life. WW Norton & Company. [Google Scholar]

- Kevane, M., & Koopmann-Holm, B. (2021). Improving reverse correlation analysis of faces: Diagnostics of order effects, runs, rater agreement, and image pairs. Behavior Research Methods, 53(4), 1609–1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiefer, T. (2005). Feeling bad: Antecedents and consequences of negative emotions in ongoing change. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 26(8), 875–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitayama, S., Ishii, K., Imada, T., Takemura, K., & Ramaswamy, J. (2006). Voluntary Settlement and the Spirit of Independence: Evidence from Japan’s ‘Northern Frontier’. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 91, 369–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitayama, S., Park, H., Sevincer, A. T., Karasawa, M., & Uskul, A. K. (2009). A cultural task analysis of implicit independence: Comparing North America, Western Europe, and East Asia. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 97(2), 236–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitayama, S., Salvador, C. E., Nanakdewa, K., Rossmaier, A., San Martin, A., & Savani, K. (2022). Varieties of interdependence and the emergence of the Modern West: Toward the globalizing of psychology. The American Psychologist, 77(9), 991–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koopmann-Holm, B., Bartel, K., Bin Meshar, M., & Yang, H. E. (2020a). Seeing the whole picture? Avoided negative affect and processing of others’ suffering. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 46(9), 1363–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koopmann-Holm, B., Bruchmann, K., Fuchs, M., & Pearson, M. (2021). What constitutes a compassionate response? The important role of culture. Emotion, 21(8), 1610–1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koopmann-Holm, B., Sze, J., Jinpa, T., & Tsai, J. L. (2020b). Compassion meditation increases optimism towards a transgressor. Cognition and Emotion, 34(5), 1028–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koopmann-Holm, B., & Tsai, J. L. (2014). Focusing on the negative: Cultural differences in expressions of sympathy. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 107(6), 1092–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krys, K., Vignoles, V. L., de Almeida, I., & Uchida, Y. (2022a). Outside the “Cultural Binary”: Understanding Why Latin American Collectivist Societies Foster Independent Selves. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 17(4), 1166–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krys, K., Yeung, J. C., Capaldi, C. A., Lun, V. M.-C., Torres, C., van Tilburg, W. A. P., Bond, M. H., Zelenski, J. M., Haas, B. W., Park, J., Maricchiolo, F., Vauclair, C.-M., Kosiarczyk, A., Kocimska-Zych, A., Kwiatkowska, A., Adamovic, M., Pavlopoulos, V., Fülöp, M., Sirlopu, D., … Vignoles, V. L. (2022b). Societal emotional environments and cross-cultural differences in life satisfaction: A forty-nine country study. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 17(1), 117–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuppens, P., Realo, A., & Diener, E. (2008). The role of positive and negative emotions in life satisfaction judgment across nations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95(1), 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larco, S. S., Romo, M. G., Garcés, M. S., & Koopmann-Holm, B. (2024). People in Ecuador and the United States conceptualize compassion differently: The role of avoided negative affect. Emotion, 24(6), 1456–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Londoño-Cortés, M. A., Idárraga-López, M. C., Mercadillo, R. E., Cudris-Torres, L., & Javela, J. J. (2023). Moral emotions in the Latin-America: A socio-cultural and socioeconomic analysis. Current Psychiatry Research and Reviews Formerly: Current Psychiatry Reviews, 19(2), 147–158. [Google Scholar]

- Lugo-Candelas, C. I., Harvey, E. A., & Breaux, R. P. (2015). Emotion socialization practices in Latina and European-American mothers of preschoolers with behavior problems. Journal of Family Studies, 21(2), 144–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundqvist, D., & Litton, J. (1998). The averaged karolinska directed emotional faces. Karolinska Institute, Department of Clinical Neuroscience, Section Psychology. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, D. S., Correll, J., & Wittenbrink, B. (2015). The Chicago face database: A free stimulus set of faces and norming data. Behavior Research Methods, 47(4), 1122–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maio, G. R., & Esses, V. M. (2001). The need for affect: Individual differences in the motivation to approach or avoid emotions. Journal of Personality, 69, 583–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsumoto, D., Yoo, S. H., Fontaine, J., Anguas-Wong, A. M., Arriola, M., Ataca, B., Bond, M. H., Boratav, H. B., Breugelmans, S. M., Cabecinhas, R., Chae, J., Chin, W. H., Comunian, A. L., Degere, D. N., Djunaidi, A., Fok, H. K., Friedlmeier, W., Ghosh, A., Glamcevski, M., … Grossi, E. (2008). Mapping expressive differences around the world: The relationship between emotional display rules and individualism versus collectivism. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 39(1), 55–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauss, I. B., Tamir, M., Anderson, C. L., & Savino, N. S. (2011). Can seeking happiness make people unhappy? Paradoxical effects of valuing happiness. Emotion, 11(4), 807–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McAdams, D. (2004). The redemptive self: Narrative identity in America today. In The Self and Memory (pp. 95–116). Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ministero, L. M., Poulin, M. J., Buffone, A. E., & DeLury, S. (2018). Empathic concern and the desire to help as separable components of compassionate responding. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 44(4), 475–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyamoto, Y., Ma, X., & Petermann, A. G. (2014). Cultural differences in hedonic emotion regulation after a negative event. Emotion, 14(4), 804–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murillo, N. (1976). The Mexican American family. In C. A. Hernandez, M. J. Haug, & N. N. Wagner (Eds.), Chicanos: Social and psychological perspectives (pp. 97–108). Mosby, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, C. V., Jacobs, J. I. L., Rock, A. J., & Clark, G. I. (2021). Attachment style, thought suppression, self-compassion and depression: Testing a serial mediation model. PLoS ONE, 16(1), e0245056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. (2018). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 21 May 2025).

- Rezende, C. B. (2008). Stereotypes and national identity: Experiencing the Emotional Brazilian. Identities: Global Studies in Culture and Power, 15, 103–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, M. D., & Clore, G. L. (2002). Belief and feeling: Evidence for an accessibility model of emotional self-report. Psychological Bulletin, 128(6), 934–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruby, M. B., Falk, C. F., Heine, S. J., Villa, C., & Silberstein, O. (2012). Not all collectivisms are equal: Opposing preferences for ideal affect between East Asians and Mexicans. Emotion, 12(6), 1206–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvador, C. E., Idrovo Carlier, S., Ishii, K., Torres Castillo, C., Nanakdewa, K., San Martin, A., Savani, K., & Kitayama, S. (2024). Emotionally expressive interdependence in Latin America: Triangulating through a comparison of three cultural zones. Emotion, 24(3), 820–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S. H., & Bardi, A. (2001). Value hierarchies across cultures: Taking a similarities perspective. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 32(3), 268–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweiger, I., Cuenca, C., & Fernández-Dols, J. M. (2021, February 9–13). A conceptual approximation to the spanish equivalent of compassion [Poster presentation]. Annual SPSP 2021 Virtual Convention, Online. [Google Scholar]

- Senft, N., Campos, B., Shiota, M. N., & Chentsova-Dutton, Y. E. (2021). Who emphasizes positivity? An exploration of emotion values in people of Latino, Asian, and European heritage living in the United States. Emotion, 21(4), 707–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seow, J. H., Du, H., & Koopmann-Holm, B. (2025). What is a compassionate face? Avoided negative affect explains differences between U.S. Americans and Chinese. Cognition and Emotion, 39(3), 704–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaver, P., Schwartz, J., Kirson, D., & O’connor, C. (1987). Emotion knowledge: Further exploration of a prototype approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52(6), 1061–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto, J. A., Levenson, R. W., & Ebling, R. (2005). Cultures of moderation and expression: Emotional experience, behavior, and physiology in Chinese Americans and Mexican Americans. Emotion, 5, 154–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stearns, P. N. (1994). American cool: Constructing a twentieth-century emotional style. New York University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tousignant, M. (1984). Pena in the Ecuadorian Sierra: A psychoanthropological analysis of sadness. Culture, Medicine, and Psychiatry: An International Journal of Cross-Cultural Health Research, 8(4), 381–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tousignant, M., & Maldonado, M. (1989). Sadness, depression and social reciprocity in highland Ecuador. Social Science & Medicine, 28(9), 899–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, J. L., Knutson, B., & Fung, H. (2006). Cultural variation in affect valuation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 90, 288–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hernandez, N.; Llerena, L.; Morales, E.; Tillman, J.; Mendez, D.R.; Koopmann-Holm, B. Compassion in Mexico and the United States: Unpacking Cultural Differences. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 732. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060732

Hernandez N, Llerena L, Morales E, Tillman J, Mendez DR, Koopmann-Holm B. Compassion in Mexico and the United States: Unpacking Cultural Differences. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(6):732. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060732

Chicago/Turabian StyleHernandez, Naomi, Liam Llerena, Evita Morales, Jack Tillman, David Ruiz Mendez, and Birgit Koopmann-Holm. 2025. "Compassion in Mexico and the United States: Unpacking Cultural Differences" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 6: 732. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060732

APA StyleHernandez, N., Llerena, L., Morales, E., Tillman, J., Mendez, D. R., & Koopmann-Holm, B. (2025). Compassion in Mexico and the United States: Unpacking Cultural Differences. Behavioral Sciences, 15(6), 732. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060732