How Does Accountability Exacerbate Job Burnout in the Public Sector? Exploratory Research in Production Supervision in China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Felt Accountability

2.2. Job Burnout

2.3. The Relationship Between Felt Accountability and Job Burnout

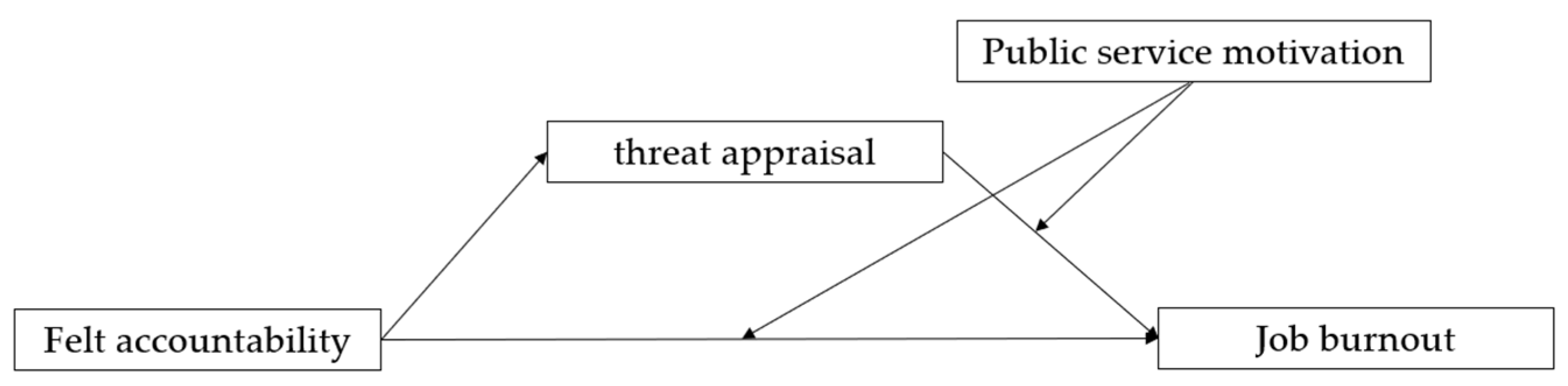

2.4. The Mediating Role of Threat Appraisal

2.5. The Moderating Role of Public Service Motivation

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Sample and Data Collection

3.2. Variable Measurement

4. Results

4.1. Scale Reliability and Validity Test and Common Method Bias Test

4.1.1. Reliability and Validity Test

4.1.2. Homologous Bias Test

4.2. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis

4.3. Main Effect Test and Mediation Effect Test

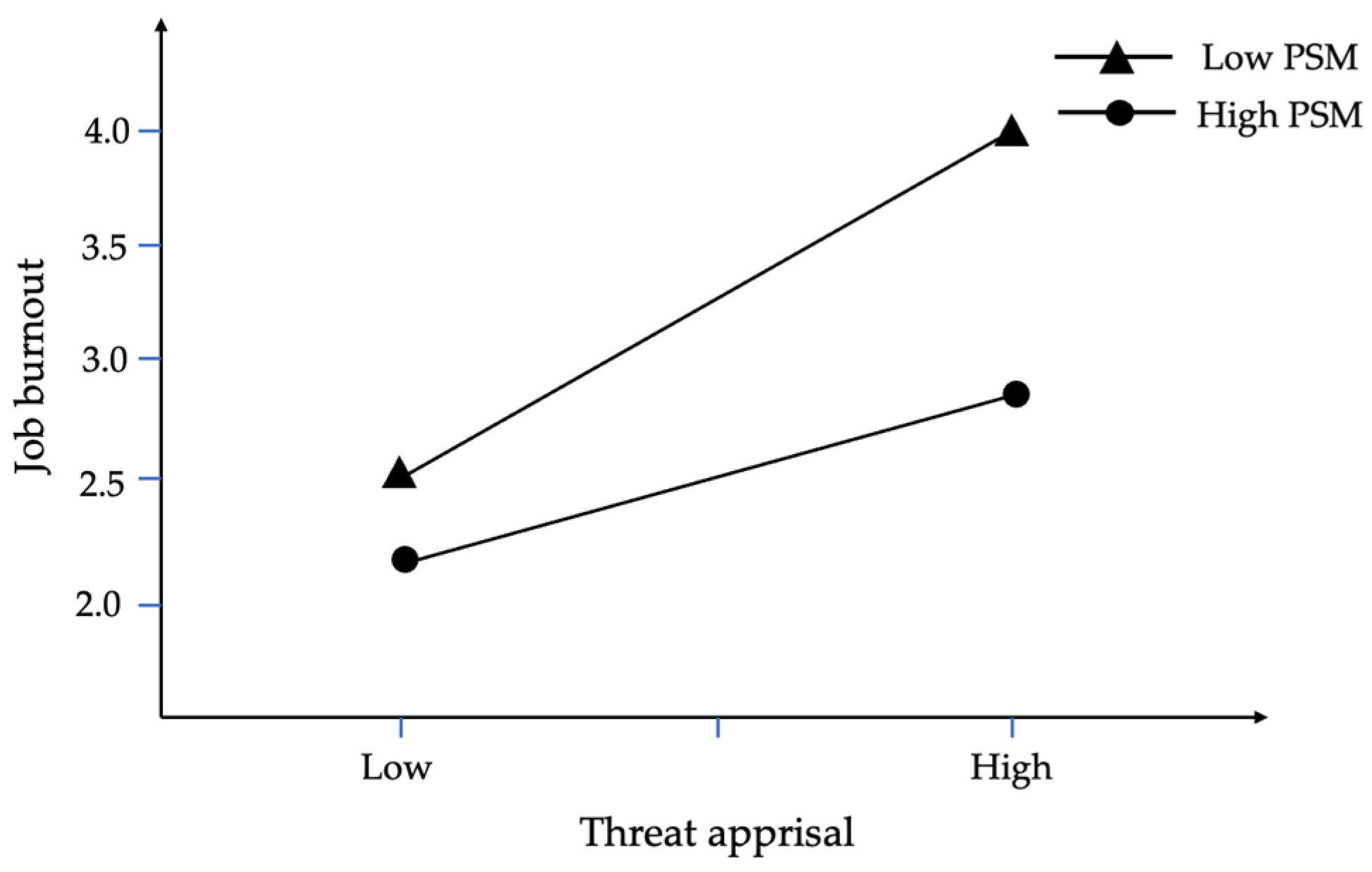

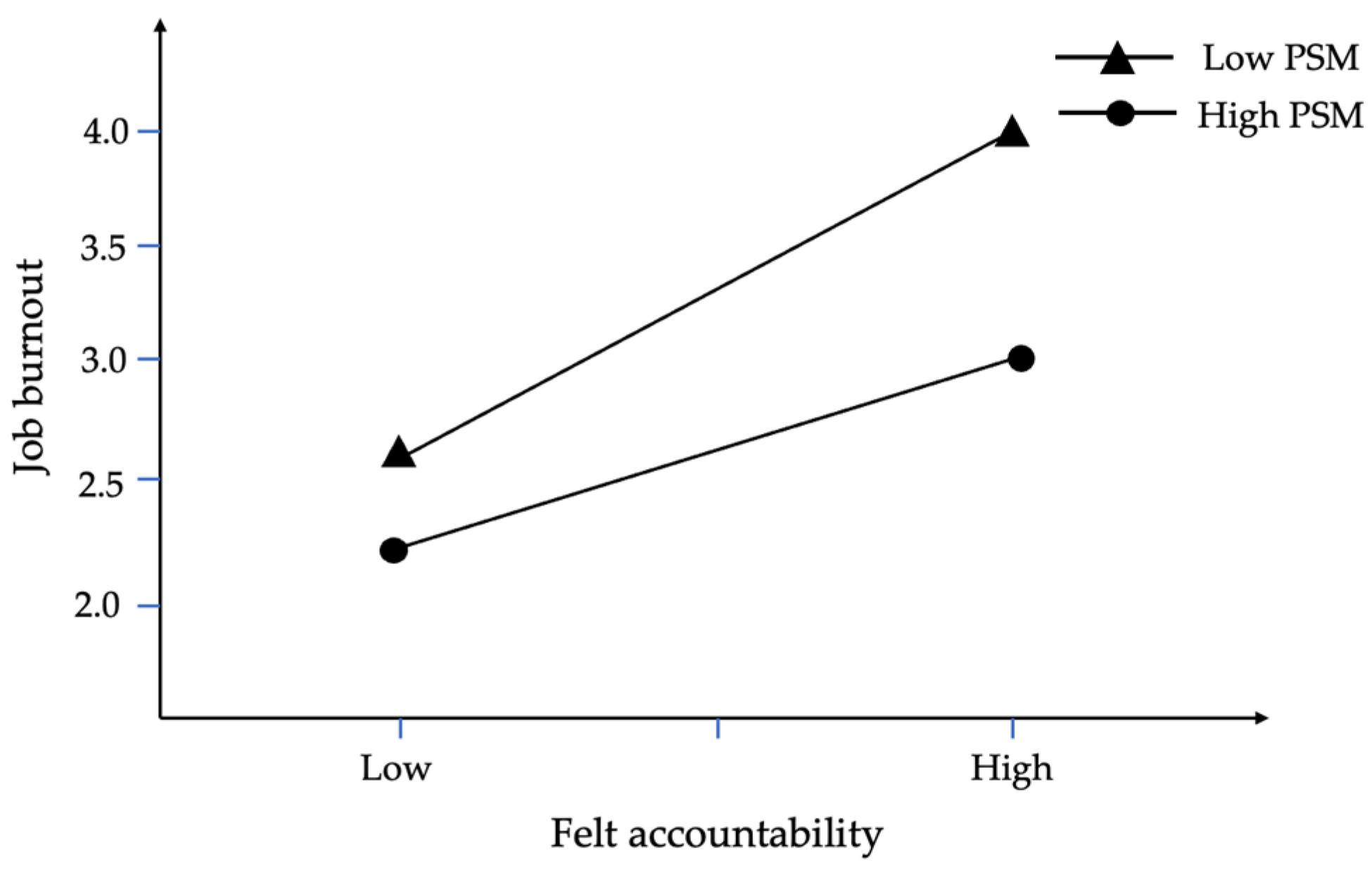

4.4. Moderated Mediation Effect Test

5. Discussion and Implications

5.1. Main Findings

5.2. Implications

5.3. Research Limitations and Future Directions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aleksovska, M., Schillemans, T., & Grimmelikhuijsen, S. (2022). Management of multiple accountabilities through setting priorities: Evidence from a cross-national conjoint experiment. Public Administration Review, 82(1), 132–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, M. B. G., & Iwanicki, E. F. (1984). Teacher motivation and its relationship to burnout. Educational Administration Quarterly, 20(2), 109–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2017). Job demands–resources theory: Taking stock and looking forward. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 22(3), 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bovens, M., Schillemans, T., & Hart, P. T. (2008). Does public accountability work? An assessment tool. Public Administration, 86(1), 225–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breaux, D. M., Munyon, T. P., Hochwarter, W. A., & Ferris, G. R. (2009). Politics as a moderator of the accountability—job satisfaction relationship: Evidence across three studies. Journal of Management, 35(2), 307–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, R. X., & Hu, W. (2022). The tendency for pro-social rule breaking by bureauracts in the context of a public crisis: Evidence from a survey experiment. China Public Administration Review, 4(2), 5–42. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Cavanaugh, M. A., Boswell, W. R., Roehling, M. V., & Boudreau, J. W. (2000). An empirical examination of self-reported work stress among US managers. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85(1), 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E., & Bakker, A. B. (2011). The job demands–resources model: Challenges for future research. South African Journal of Industrial Psychology, 37(2), 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewi, N. P. R. A., & Ramantha, I. W. (2019). Effect of conflict and unclear role on auditor performance with emotional quotient as moderating variable. International Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities, 3(3), 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drach-Zahavy, A., & Erez, M. (2002). Challenge versus threat effects on the goal-performance relationship. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 88(2), 667–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folkman, S., & Lazarus, R. S. (1986). Stress processes and depressive symptomatology. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 95(2), 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freudenberger. (1974). Staff burnout. Journal of Social Issues, 30, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelfand, M. J., Lim, B. C., & Raver, J. L. (2004). Culture and accountability in organizations: Variations in forms of social control across cultures. Human Resource Management Review, 14(1), 135–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giauque, D., Anderfuhren-Biget, S., & Varone, F. (2013). Stress perception in public organisations: Expanding the job demands–job resources model by including public service motivation. Review of Public Personnel Administration, 33(1), 58–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, A. R., Faria, S., & Gonçalves, A. M. (2013). Cognitive appraisal as a mediator in the relationship between stress and burnout. Work & Stress, 27(4), 351–367. [Google Scholar]

- Goodin, R., Bovens, M., & Schillemans, T. (2014). Public accountability. In Oxford Handbook of Public Accountability. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Grimmelikhuijsen, S., Jilke, S., Olsen, A. L., & Tummers, L. (2017). Behavioral public administration: Combining insights from public administration and psychology. Public Administration Review, 77(1), 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, A. T., Frink, D. D., Ferris, G. R., Hochwarter, W. A., Kacmar, C. J., & Bowen, M. G. (2003). Accountability in human resources management. In C. A. Schriesheim, & L. Neider (Eds.), New directions in human resource management (pp. 26–63). Information Age Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, A. T., Royle, M. T., Brymer, R. A., Perrewé, P. L., Ferris, G. R., & Hochwarter, W. A. (2006). Relationships between felt accountability as a stressor and strain reactions: The neutralizing role of autonomy across two studies. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 11(1), 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y., & Perry, J. L. (2020a). Conceptual bases of employee accountability: A psychological approach. Perspectives on Public Management and Governance, 3(4), 288–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y., & Perry, J. L. (2020b). Employee accountability: Development of a multidimensional scale. International Public Management Journal, 23(2), 224–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S. E., Halbesleben, J., Neveu, J. P., & Westman, M. (2018). Conservation of resources in the organizational context: The reality of resources and their consequences. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 5(1), 103–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochwarter, W. A., Perrewé, P. L., Hall, A. T., & Ferris, G. R. (2005). Negative affectivity as a moderator of the form and magnitude of the relationship between felt accountability and job tension. Journal of Organizational Behavior: The International Journal of Industrial, Occupational and Organizational Psychology and Behavior, 26(5), 517–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hood, C. (2013). The blame game: Spin, bureaucracy, and self-preservation in government. Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hopstaken, J. F., van der Linden, D., Bakker, A. B., & Kompier, M. A. J. (2014). A multifaceted investigation of the link between mental fatigue and task disengagement. Psychophysiology, 52(3), 305–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, D., & Kahn, R. (2015). The social psychology of organizations. In Organizational behavior 2 (pp. 152–168). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Kuo, C. C., Ni, Y. L., Wu, C. H., Duh, R. R., Chen, M. Y., & Chang, C. (2022). When can felt accountability promote innovative work behavior? The role of transformational leadership. Personnel Review, 51(7), 1807–1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, R. S., DeLongis, A., Folkman, S., & Gruen, R. (1985). Stress and adaptational outcomes: The problem of confounded measures. American Psychologist, 40(7), 770–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1987). Transactional theory and research on emotions and coping. European Journal of Personality, 1(3), 141–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C. P., & Shi, C. (2003). The influence of distributive justice and procedural justice on job burnout. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 35(5), 677–684. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y. W., Qin, X. L., & Koppenjan, J. (2022). Accountability through public participation? Experience from the ten-thousand-citizen review in Nanjing, China. Journal of Public Policy, 42(1), 43–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H. C., & Zhao, Y. X. (2020). On adminstration public interest litigation in safe production. Journal of Southwest Minzu University (Humanities and Social Sciences Edition, 41(1), 44–50. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X., Ren, P., Lv, X., & Li, S. (2024). Service experience and customers’ eWOM behavior on social media platforms: The role of platform symmetry. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 119, 103735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackey, J. D., Brees, J. R., McAllister, C. P., Zorn, M. L., Martinko, M. J., & Harvey, P. (2018). Victim and culprit? The effects of entitlement and felt accountability on perceptions of abusive supervision and perpetration of workplace bullying. Journal of Business Ethics, 153, 659–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C., & Jackson, S. E. (1981). The measurement of experienced burnout. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 2(2), 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C., & Leiter, M. P. (2000). The truth about burnout: How organizations cause personal stress and what to do about it. John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Maslach, C., & Leiter, M. P. (2016). Understanding the burnout experience: Recent research and its implications for psychiatry. World Psychiatry, 15(2), 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C., Schaufeli, W. B., & Leiter, M. P. (2001). Job burnout. Annual Review of Psychology, 52(1), 397–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mero, N. P., Guidice, R. M., & Werner, S. (2014). A field study of the antecedents and performance consequences of perceived accountability. Journal of Management, 40(6), 1627–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, H., Jiang, M., & Wang, X. (2013). The impact of political cycle: Evidence from coalmine accidents in China. Journal of Comparative Economics, 41(4), 995–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noesgaard, M. S., & Hansen, J. R. (2018). Work engagement in the public service context: The dual perceptions of job characteritics. International Journal of Public Administration, 41(13), 1047–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, J. P. (2017). Democratic accountability, political order, and change: Exploring accountability processes in an era of European transformation. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ossege, C. (2012). Accountability—Are we better off without it? An empirical study on the effects of accountability on public managers’ work behaviour. Public Management Review, 14(5), 585–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overman, S. (2021). Aligning accountability arrangements for ambiguous goals: The case of museums. Public Management Review, 23(8), 1139–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overman, S., & Schillemans, T. (2022). Toward a public administration theory of felt accountability. Public Administration Review, 82(1), 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, S. (2006). The web of managerial accountability: The impact of reinventing government. Administration & Society, 38(2), 166–197. [Google Scholar]

- Rabbi, M. F., & Sabharwal, M. (2024). Understanding accountability overload: Concept and consequences in public sector organizations. International Journal of Public Administration, 48(2), 115–133. [Google Scholar]

- Resh, W. G., Marvel, J. D., & Wen, B. (2018). The persistence of prosocial work effort as a function of mission match. Public Administration Review, 78(1), 116–125. [Google Scholar]

- Schaufeli, W. B., & Enzmann, D. (1998). The burnout companion to study and practice: A critical analysis. Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Schillemans, T. (2016). Calibrating Public Sector Accountability: Translating experimental findings to public sector accountability. Public Management Review, 18(9), 1400–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schillemans, T., Overman, S., Fawcett, P., Flinders, M., Fredriksson, M., Laegreid, P., Maggetti, M., Papadopoulos, Y., Rubecksen, K., Rykkja, L. H., & Wood, M. (2021). Understanding felt accountability: The institutional antecedents of the felt accountability of agency-CEO’s to central government. Governance, 34(3), 893–916. [Google Scholar]

- Vandenabeele, W. (2007). Towards a public administration theory of public service motivation: An institutional approach. Public Management Review, 9(4), 545–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B., Wu, C., Kang, L., Reniers, G., & Huang, L. (2018). Work safety in China’s Thirteenth Five-Year plan period (2016–2020): Current status, new challenges and future tasks. Safety Science, 104, 164–178. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, B. E., Christensen, R. K., & Pandey, S. K. (2013). Measuring public service motivation: Exploring the equivalence of existing global measures. International Public Management Journal, 16(2), 197–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., & Liu, B. (2023). Examining the double-edged nature of PSM on burnout: The mediating role of challenge stress and hindrance stress. Public Personnel Management, 53(2), 203–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Latent Variables | Observed Variables |

|---|---|

| Attributability (FA1) | FA1-1: What I do is noticed by others in my organization. |

| FA1-2: If I make a mistake, I will be caught. | |

| FA1-3: I am constantly watched to see if I follow my organization’s policies and procedures | |

| Observability (FA2) | FA2-1: Anyone outside my organization can tell whether I’m doing well in my job. |

| FA2-2: My errors can be easily spotted outside my organization. | |

| FA2-3: People outside my organization are interested in my job performance. | |

| Evaluability (FA3) | FA3-1: The outcomes of my work are rigorously evaluated. |

| FA3-2: My work efforts are rigorously evaluated. | |

| FA3-3: I expect to receive frequent feedback from my supervisor. | |

| Answerability (FA4) | FA4-1: I could not easily get away with making a false statement to justify my performance. |

| FA4-2: I am always required to follow strict organizational policies or procedures. | |

| FA4-3: I am not allowed to make excuses to avoid blame in my organization. | |

| Consequentiality (FA5) | FA5-1: If I perform well, I will be rewarded. |

| FA5-2: Good effort on my part will ultimately be rewarded. | |

| FA5-3: If I do my job well, my organization will benefit from it. | |

| Threat appraisal (TA) | TA-1: The task seems like a threat to me. |

| TA-2: I’m worried that the task might reveal my weaknesses. | |

| TA-3: The task seems long and tiresome. | |

| TA-4: I’m worried that the task might threaten my self-esteem. | |

| Public service motivation (PSM) | PSM-1: It is very important to me to engage in meaningful public service |

| PSM-2: Everyday events often remind me that the people in my life are indeed interdependent. | |

| PSM-3: Contributing to society is more meaningful than personal achievement | |

| PSM-4: I am ready to make sacrifices for the good of society | |

| PSM-5: Even if I am ridiculed, I will still strive to fight for the rights of others | |

| Exhaustion (JB-1) | JB1-1: Safe production supervision and law enforcement work makes me physically and mentally exhausted |

| JB1-2: I feel exhausted at the end of a day’s work. | |

| JB1-3: I feel tired when I think about starting a new day at work. | |

| JB1-4: Working all day is really stressful for me. | |

| JB1-5: I feel like I’m going to collapse from work. | |

| Cynicism (JB-2) | JB2-1: I am becoming less and less interested in work |

| JB2-2: I am not as enthusiastic about my work as before. | |

| JB2-3: I doubt the meaning of my work | |

| JB2-4: I care less and less about whether the work I do contributes | |

| Inefficacy (JB-3) | JB3-1: I can effectively solve problems that arise at work |

| JB3-2: I feel like I am making a useful contribution to the work | |

| JB3-3: I think I’m good at my job. | |

| JB3-4: I feel great when I accomplish something at work. | |

| JB3-5: I have accomplished a lot of valuable work | |

| JB3-6: I am confident that I can complete various tasks effectively |

| Variable | Cronbach’s α | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Felt accountability | 0.881 | 0.894 | 0.631 |

| Threat appraisal | 0.828 | 0.832 | 0.603 |

| Public service motivation | 0.912 | 0.891 | 0.635 |

| Job burnout | 0.887 | 0.910 | 0.671 |

| CMIN/DF | RMR | IFI | TLI | CFI | RMSEA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original model + common factors | 2.512 | 0.041 | 0.978 | 0.972 | 0.977 | 0.062 |

| Original model | 2.487 | 0.057 | 0.968 | 0.962 | 0.968 | 0.054 |

| Three factors | 2.955 | 0.068 | 0.897 | 0.889 | 0.897 | 0.069 |

| Two factors | 5.135 | 0.136 | 0.788 | 0.755 | 0.788 | 0.093 |

| Single factors | 5.538 | 0.104 | 0.756 | 0.733 | 0.756 | 0.105 |

| Minimum | Maximum | Mean | Standard Deviation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Felt accountability | 1.47 | 6.47 | 3.715 | 0.949 |

| Threat appraisal | 1.00 | 6.75 | 3.808 | 1.030 |

| Public service motivation | 1.00 | 6.60 | 4.573 | 1.237 |

| Job burnout | 1.17 | 6.46 | 2.962 | 0.957 |

| Variable | Gender | Education | Age | Years of Service | FA | TA | PSM | JB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 1 | |||||||

| Education | −0.050 | 1 | ||||||

| Age | 0.084 | −0.106 * | 1 | |||||

| Years of service | 0.090 | −0.066 | 0.671 ** | 1 | ||||

| FA | −0.015 * | 0.159 ** | −0.052 | −0.091 | 1 | |||

| TA | −0.063 | 0.116 ** | −0.102 ** | −0.144 ** | 0.778 ** | 1 | ||

| PSM | −0.021 | −0.085 | 0.097 | 0.039 | 0.186 ** | 0.169 ** | 1 | |

| JB | −0.079 | 0.148 ** | −0.109 ** | −0.113 ** | 0.805 ** | 0.803 ** | −0.206 ** | 1 |

| Variable | FA | TA | PSM | Gender | Age | Education | Years of Serivce |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VIF | 2.603 | 2.589 | 1.064 | 1.017 | 1.051 | 1.848 | 1.840 |

| Effect Type | Effect | BootSE | BootLLCI | BootULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Effect | 0.8061 | 0.0298 | 0.7475 | 0.8648 |

| Direct effect | 0.4631 | 0.0417 | 0.3811 | 0.5451 |

| Indirect effect | 0.3430 | 0.0355 | 0.2766 | 0.4139 |

| Variable | Threat Apprisal | Job Burnout | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | t | 95%CI | β | t | 95%CI | |

| Gender | −0.125 | −1.565 | [−0.282, 0.321] | −0.959 | −0.132 | [−0.175, −0.016] |

| Education | −0.133 | −0.202 | [−0.143, 0.116] | −0.026 | 0.083 | [−0.091, 0.039] |

| Age | −0.021 | −0.330 | [−1.145, 0.103] | −0.027 | −0.092 | [−0.089, 0.035] |

| Years of service | −0.075 | −1.331 | [−0.185, 0.036] | 0.032 | 0.040 | [−0.023, 0.088] |

| FA | 0.785 | 21.165 *** | [0.712, 0.858] | 0.476 | 17.223 *** | [0.421, 0.529] |

| TA | 0.432 | 16.934 *** | [0.381, 0.482] | |||

| PSM | −0.282 | −18.432 *** | [−0.321, −0.251] | |||

| FA*PSM | −0.084 | −2.987 *** | [−0.171, −0.070] | |||

| TA*PSM | −0.068 | −2.582 *** | [−0.132, −0.043] | |||

| R2 | 0.542 | 0.878 | ||||

| ΔR2 | 0.137 | 0.115 | ||||

| F | 95.621 *** | 286.453 *** | ||||

| PSM | Effect | BootSE | BootLLCI | BootULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low (−1SD) | 0.3839 | 0.0365 | 0.3182 | 0.4628 |

| Mean | 0.3390 | 0.0272 | 0.2893 | 0.3951 |

| High (+1SD) | 0.2940 | 0.0328 | 0.2301 | 0.3608 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fang, Z.; Zhang, Q. How Does Accountability Exacerbate Job Burnout in the Public Sector? Exploratory Research in Production Supervision in China. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 747. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060747

Fang Z, Zhang Q. How Does Accountability Exacerbate Job Burnout in the Public Sector? Exploratory Research in Production Supervision in China. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(6):747. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060747

Chicago/Turabian StyleFang, Zhiyi, and Qilin Zhang. 2025. "How Does Accountability Exacerbate Job Burnout in the Public Sector? Exploratory Research in Production Supervision in China" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 6: 747. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060747

APA StyleFang, Z., & Zhang, Q. (2025). How Does Accountability Exacerbate Job Burnout in the Public Sector? Exploratory Research in Production Supervision in China. Behavioral Sciences, 15(6), 747. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060747