Development and Validation of Polypharmacy-Related Psychological Distress Scale (PPDS): A Preliminary Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

Theoretical Framework

2. Materials and Methods

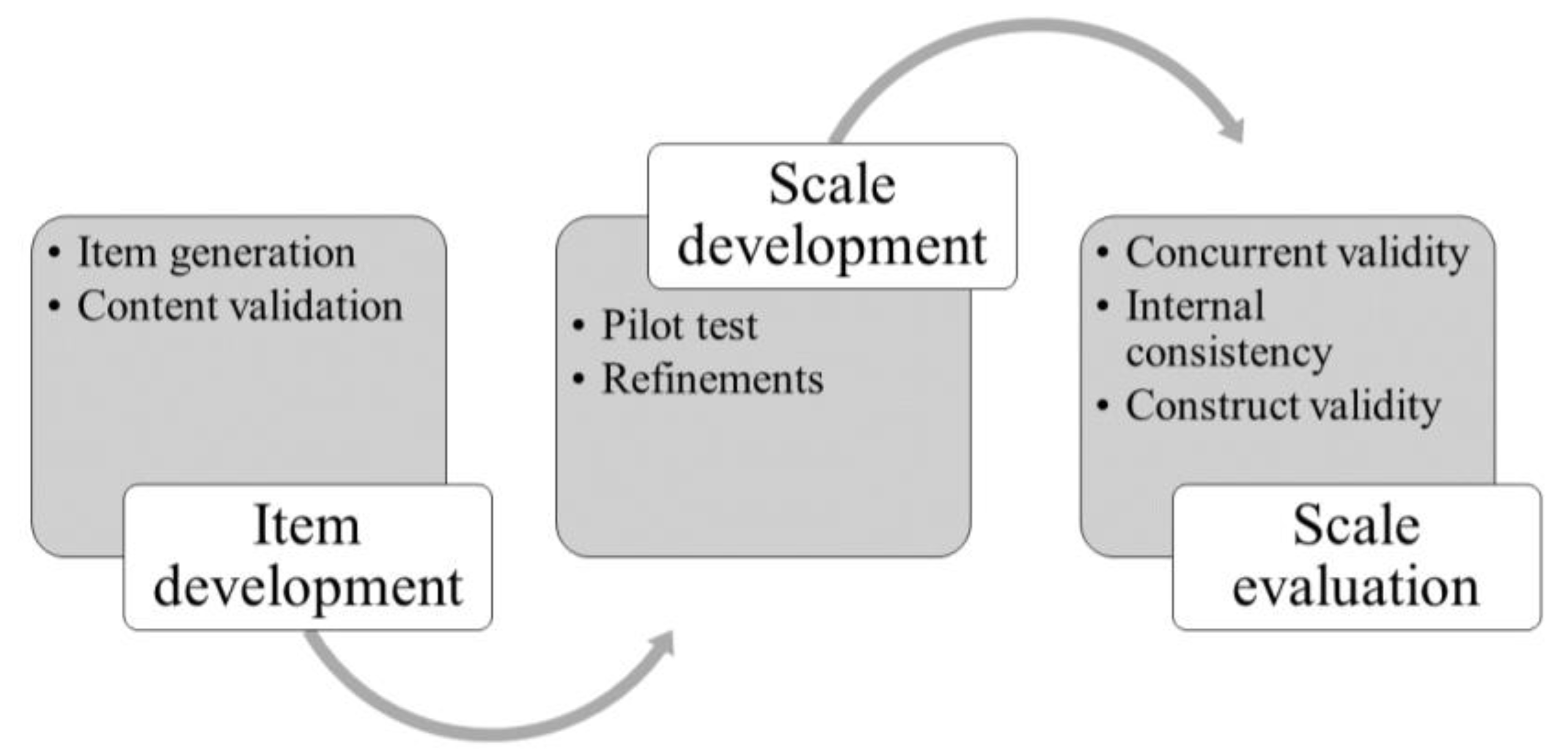

2.1. Phase 1: Item Development

2.1.1. Item Generation

2.1.2. Content Validation

2.2. Phase 2: Scale Development

2.3. Phase 3: Scale Assessment

2.3.1. Study Design

2.3.2. Sample

2.3.3. Measures

2.3.4. Data Collection

2.3.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Content Validity

3.2. Face Validity

3.3. Cross-Sectional Validation Study

3.4. Concurrent Validity

3.5. Internal Consistency

3.6. Inter-Item Correlation

3.7. CFA Factor Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Implications for Research and Practice

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ando, T., abe, Y., Arai, Y., Sasaki, T., & Fujishima, S. (2023). Association of care fragmentation with polypharmacy and inappropriate medication among older adults with multimorbidity. The Annals of Family Medicine, 21(1), 3570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2016). Older australians. Australian bureau of statistics. Available online: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/older-people/older-australians/contents/education-and-skills (accessed on 11 October 2024).

- Awad, A., Alhadab, A., & Albassam, A. (2020). Medication-related burden and medication adherence among geriatric patients in kuwait: A cross-sectional study. Frontiers in Pharmacology, 11, 1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ágh, T., van Boven, J. F., Wettermark, B., Menditto, E., Pinnock, H., Tsiligianni, I., Petrova, G., Potočnjak, I., Kamberi, F., & Kardas, P. (2021). A cross-sectional survey on medication management practices for noncommunicable diseases in Europe during the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers in Pharmacology, 12, 685696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boateng, G. O., Neilands, T. B., Frongillo, E. A., Melgar-Quiñonez, H. R., & Young, S. L. (2018). Best practices for developing and validating scales for health, social, and behavioral research: A primer. Frontiers in Public Health, 6, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T. A. (2015). Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research (2nd ed.). The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Celano, C. M., Freudenreich, O., Fernandez-Robles, C., Stern, T. A., Caro, M. A., & Huffman, J. C. (2011). Depressogenic effects of medications: A review. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 13(1), 109–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C., & Bai, J. (2022). Association between polypharmacy, anxiety, and depression among Chinese older adults: Evidence from the Chinese longitudinal healthy longevity survey. Clinical Interventions in Aging, 17, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C., Yu, H., & Wang, Q. (2023). Nurses’ experiences concerning older adults with polypharmacy: A meta-synthesis of qualitative findings. Healthcare, 11(3), 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cicchetti, D. V., & Sparrow, S. A. (1981). Developing criteria for establishing interrater reliability of specific items: Applications to assessment of adaptive behavior. American Journal of Mental Deficiency, 86(2), 127–137. [Google Scholar]

- Delara, M., Murray, L., Jafari, B., Bahji, A., Goodarzi, Z., Kirkham, J., Chowdhury, M., & Seitz, D. P. (2022). Prevalence and factors associated with polypharmacy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Geriatrics, 22(1), 601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, G. L. (1980). The clinical application of the biopsychosocial model. American Journal of Psychiatry, 137(5), 535–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksen, C. U., Kyriakidis, S., Christensen, L. D., Jacobsen, R., Laursen, J., Christensen, M. B., & Frølich, A. (2020). Medication-related experiences of patients with polypharmacy: A systematic review of qualitative studies. BMJ Open, 10(9), e036158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fortin, M., & Stewart, M. (2021). Implementing patient-centred integrated care for multiple chronic conditions: Evidence-informed framework. Canadian Family Physician, 67(4), 235–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagnier, J. J., Lai, J., Mokkink, L. B., & Terwee, C. B. (2021). COSMIN reporting guideline for studies on measurement properties of patient-reported outcome measures. Quality of Life Research, 30(8), 2197–2218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gignac, G. E., & Szodorai, E. T. (2016). Effect size guidelines for individual differences researchers. Personality and Individual Differences, 102, 74–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, A., Matthews, F., Hanratty, B., & Todd, A. (2022). How should a physician assess medication burden and polypharmacy? Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy, 23(1), 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kannis-Dymand, L., Salguero, J. M., Ramos-Cejudo, J., & Novaco, R. W. (2019). Dimensions of Anger Reactions-Revised (DAR-R): Validation of a brief anger measure in Australia and Spain. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 75(7), 1233–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemper, C. J., Trapp, S., Kathmann, N., Samuel, D. B., & Ziegler, M. (2019). Short versus long scales in clinical assessment: Exploring the trade-off between resources saved and psychometric quality lost using two measures of obsessive-compulsive symptoms. Assessment, 26(5), 767–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, R. C., Andrews, G., Colpe, L. J., Hiripi, E., Mroczek, D. K., Normand, S. L., Walters, E. E., & Zaslavsky, A. M. (2002). Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychological Medicine, 32(6), 959–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khezrian, M., McNeil, C. J., Murray, A. D., & Myint, P. K. (2020). An overview of prevalence, determinants and health outcomes of polypharmacy. Therapeutic Advances in Drug Safety, 11, 2042098620933741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S., Lee, H., Park, J., Kang, J., Rahmati, M., Rhee, S. Y., & Yon, D. K. (2024). Global and regional prevalence of polypharmacy and related factors, 1997–2022: An umbrella review. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 124, 105465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, P. (1994). An easy guide to factor analysis. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., Williams, J. B., & Löwe, B. (2009). An ultra-brief screening scale for anxiety and depression: The PHQ-4. Psychosomatics, 50(6), 613–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leventhal, H., Phillips, L. A., & Burns, E. (2016). The common-sense model of self-regulation (CSM): A dynamic framework for understanding illness self-management. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 39(6), 935–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.-L., & Yao, G. (2014). Concurrent Validity. In A. C. Michalos (Ed.), Encyclopedia of quality of life and well-being research (pp. 1184–1185). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mair, A., Wilson, M., & Dreischulte, T. (2020). Addressing the challenge of polypharmacy. Annual Review of Pharmacology and Toxicology, 60, 661–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masnoon, N., Shakib, S., Kalisch-Ellett, L., & Caughey, G. E. (2017). What is polypharmacy? A systematic review of definitions. BMC Geriatrics, 17(1), 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, C. R., Eton, D. T., Boehmer, K., Gallacher, K., Hunt, K., MacDonald, S., Mair, F. S., May, C. M., Montori, V. M., Richardson, A., Rogers, A. E., & Shippee, N. (2014). Rethinking the patient: Using burden of treatment theory to understand the changing dynamics of illness. BMC Health Services Research, 14, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonald, R. P. (1999). Test theory: A unified treatment. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- McKenna, H. P. (1994). The Delphi technique: A worthwhile research approach for nursing? Journal of Advanced Nursing, 19(6), 1221–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholson, K., Liu, W., Fitzpatrick, D., Hardacre, K. A., Roberts, S., Salerno, J., Stranges, S., Fortin, M., & Mangin, D. (2024). Prevalence of multimorbidity and polypharmacy among adults and older adults: A systematic review. The Lancet Healthy Longevity, 5(4), e287–e296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J., & Bernstein, I. (1994). Psychometric theory (3rd ed.). McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Palapinyo, S., Methaneethorn, J., & Leelakanok, N. (2021). Association between polypharmacy and depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Pharmacy Practice and Research, 51(4), 280–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penson, A., van Deuren, S., Worm-Smeitink, M., Bronkhorst, E., van den Hoogen, F. H. J., van Engelen, B. G. M., Peters, M., Bleijenberg, G., Vercoulen, J. H., Blijlevens, N., van Dulmen-den Broeder, E., Loonen, J., & Knoop, H. (2020). Short fatigue questionnaire: Screening for severe fatigue. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 137, 110229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ploubidis, G. B., McElroy, E., & Moreira, H. C. (2019). A longitudinal examination of the measurement equivalence of mental health assessments in two British birth cohorts. Longitudinal and Life Course Studies, 10(4), 471–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polit, D. F., & Beck, C. T. (2006). The content validity index: Are you sure you know what’s being reported? Critique and recommendations. Research in Nursing & Health, 29(5), 489–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polit, D. F., Beck, C. T., & Owen, S. V. (2007). Is the CVI an acceptable indicator of content validity? Appraisal and recommendations. Res Nurs Health, 30(4), 459–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revicki, D. (2014). Internal Consistency Reliability. In A. C. Michalos (Ed.), Encyclopedia of quality of life and well-being research (pp. 3305–3306). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A., Macaden, L., Kroll, T., Alhusein, N., Taylor, A., Killick, K., Stoddart, K., & Watson, M. (2019). A qualitative exploration of the experiences of community dwelling older adults with sensory impairment/s receiving polypharmacy on their pharmaceutical care journey. Age Ageing, 48(6), 895–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trizano-Hermosilla, I., & Alvarado, J. M. (2016). Best alternatives to cronbach’s alpha reliability in realistic conditions: Congeneric and asymmetrical measurements. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Wilder, L., Devleesschauwer, B., Clays, E., Pype, P., Vandepitte, S., & De Smedt, D. (2022). Polypharmacy and health-related quality of life/psychological distress among patients with chronic disease. Preventing Chronic Disease, 19, E50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventura-León, J., Sánchez-Villena, A. R., Caycho-Rodríguez, T., Barboza-Palomino, M., & Rubio, A. (2020). Fear of loneliness: Development and validation of a brief scale. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 583396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X., Liu, K., Shirai, K., Tang, C., Hu, Y., Wang, Y., Hao, Y., & Dong, J. Y. (2023). Prevalence and trends of polypharmacy in U.S. adults, 1999–2018. Global Health Research and Policy, 8(1), 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wicke, F. S., Krakau, L., Löwe, B., Beutel, M. E., & Brähler, E. (2022). Update of the standardization of the Patient Health Questionnaire-4 (PHQ-4) in the general population. Journal of Affective Disorders, 312, 310–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Please read each item carefully and respond based on your most genuine feelings over the past 14 days by marking a “√” in the corresponding box. | ||||||

| 1 | Have you felt worried or nervous in the past two weeks due to taking a lot of medications every day? | □ Completely agree | □ Agree | □ Unclear | □ Disagree | □ Completely disagree |

| 2 | Have you felt worried or nervous in the past two weeks because of the names and usages of different medications? | □ Completely agree | □ Agree | □ Unclear | □ Disagree | □ Completely disagree |

| 3 | Have you felt worried or nervous in the past two weeks about taking medications on time and in the correct dosage? | □ Completely agree | □ Agree | □ Unclear | □ Disagree | □ Completely disagree |

| 4 | Have you felt worried or nervous in the past two weeks about the necessary precautions when taking medications? | □ Completely agree | □ Agree | □ Unclear | □ Disagree | □ Completely disagree |

| Variables | Number (n) | Percentage (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age ranges (years) | 60–69 | 22 | 24.2 |

| 70–79 | 32 | 35.2 | |

| 80–89 | 31 | 34.0 | |

| >90 | 6 | 6.6 | |

| Sex | Male | 54 | 59.3 |

| Female | 37 | 40.7 | |

| Living status | Alone | 9 | 9.9 |

| With family | 71 | 78.0 | |

| Nursing home | 11 | 12.1 | |

| Education level | Illiteracy | 28 | 30.8 |

| Elementary school | 37 | 40.7 | |

| Junior high school | 19 | 20.9 | |

| Senior high school | 7 | 7.6 | |

| Duration of chronic diseases (years) | <1 | 4 | 4.3 |

| 1–5 | 19 | 20.9 | |

| 6–10 | 25 | 27.5 | |

| >10 | 43 | 47.3 | |

| Multimorbidity * | Yes | 81 | 89.0 |

| No | 10 | 11.0 |

| Items | Completely Disagree (1) | Disagree (2) | Unsure (3) | Agree (4) | Completely Agree (5) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Have you felt worried or nervous in the past two weeks due to taking a lot of medications every day? | 19 (20.9%) | 15 (16.5%) | 33 (36.3%) | 22 (24.2%) | 2 (2.2%) |

| 2. Have you felt worried or nervous in the past two weeks because of the names and usages of different medications? | 19 (20.9%) | 13 (14.3%) | 35 (38.5%) | 22 (24.2%) | 2 (2.2%) |

| 3. Have you felt worried or nervous in the past two weeks about taking medications on time and in the correct dosage? | 10 (11.0%) | 11 (12.1%) | 40 (44.0%) | 24 (26.4%) | 6 (6.6%) |

| 4. Have you felt worried or nervous in the past two weeks about the necessary precautions when taking medications? | 4 (4.4%) | 8 (8.8%) | 41 (45.1%) | 23 (25.3%) | 15 (16.5%) |

| Items | Mean | SD | Corrected Item-Total | Alpha if Item Deleted | McDonald’s Omega |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Have you felt worried or nervous in the past two weeks due to taking a lot of medications every day? | 2.69 | 1.15 | 0.702 | 0.684 | 0.924 |

| 2. Have you felt worried or nervous in the past two weeks because of the names and usages of different medications? | 2.65 | 1.13 | 0.692 | 0.691 | 0.909 |

| 3. Have you felt worried or nervous in the past two weeks about taking medications on time and in the correct dosage? | 2.88 | 1.12 | 0.670 | 0.702 | 0.922 |

| 4. Have you felt worried or nervous in the past two weeks about the necessary precautions when taking medications? | 3.20 | 1.11 | 0.359 | 0.849 | 0.920 |

| PPDS Total | Item 1 | Item 2 | Item 3 | Item 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PPDS total | 1 | 0.809 ** | 0.852 ** | 0.755 ** | 0.390 ** |

| Item 1 | 0.809 ** | 1 | 0.938 ** | 0.383 ** | −0.108 |

| Item 2 | 0.852 ** | 0.938 ** | 1 | 0.441 ** | −0.038 |

| Item 3 | 0.755 ** | 0.383 ** | 0.441 ** | 1 | 0.325 ** |

| Item 4 | 0.390 ** | −0.108 | −0.038 | 0.325 ** | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cheng, C.; Chen, X.; Wang, J.; Christensen, M. Development and Validation of Polypharmacy-Related Psychological Distress Scale (PPDS): A Preliminary Study. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 707. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15050707

Cheng C, Chen X, Wang J, Christensen M. Development and Validation of Polypharmacy-Related Psychological Distress Scale (PPDS): A Preliminary Study. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(5):707. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15050707

Chicago/Turabian StyleCheng, Cheng, Xiao Chen, Junqiao Wang, and Martin Christensen. 2025. "Development and Validation of Polypharmacy-Related Psychological Distress Scale (PPDS): A Preliminary Study" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 5: 707. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15050707

APA StyleCheng, C., Chen, X., Wang, J., & Christensen, M. (2025). Development and Validation of Polypharmacy-Related Psychological Distress Scale (PPDS): A Preliminary Study. Behavioral Sciences, 15(5), 707. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15050707