Mindful Eating and Its Relationship with Obesity, Eating Habits, and Emotional Distress in Mexican College Students

Abstract

1. Introduction

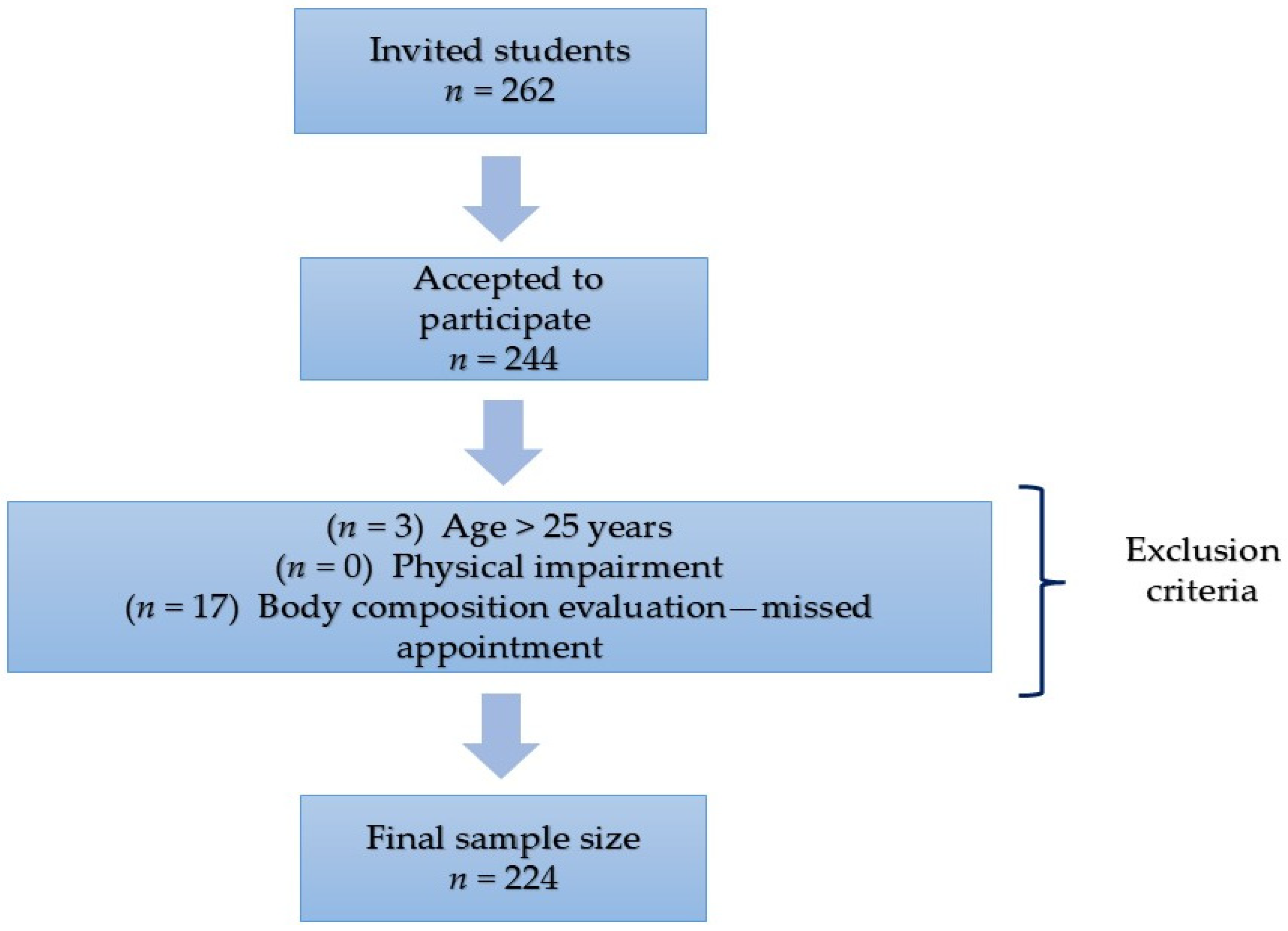

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Anthropometric Measurements

2.2. Mindful Eating Instrument

2.3. Food Frequency Questionnaire

2.4. Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale (DASS-21)

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ME | Mindful Eating |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| ME-11 | Mindful Eating Questionnaire, 11 items |

| ME-8 | Mindful Eating Questionnaire, 8 items |

| EE | Emotional Eating |

References

- Alvarenga, M. S., Scagliusi, F. B., & Philippi, S. T. (2010). Development and validity of the disordered eating attitude scale (DEAS). Perceptual and Motor Skills, 110(2), 379–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antony, M., Bieling, P., Cox, B., Enns, M., & Swinson, R. (1998). Psychometric properties of the 42-item and 21-item versions of the depression anxiety stress scales in clinical groups and a community sample. Psychological Assessment, 10(2), 176–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antúnez, Z., & Vinet, E. (2012). Escalas de Depresión, Ansiedad y Estrés (DASS-21): Validación de la versión abreviada en estudiantes universitarios chilenos. Terapia Psicologica, 30, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aucoin, M., LaChance, L., Naidoo, U., Remy, D., Shekdar, T., Sayar, N., & Cooley, K. (2021). Diet and anxiety: A scoping review. Nutrients, 13(12), 4418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baer, R. (2019). Assessment of mindfulness by self-report. Current Opinion in Psychology, 28, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beccia, A. L., Dunlap, C., Hanes, D. A., Courneene, B. J., & Zwickey, H. L. (2018). Mindfulness-based eating disorder prevention programs: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Mental Health & Prevention, 9, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beshara, M., Hutchinson, A. D., & Wilson, C. (2013). Does mindfulness matter? Everyday mindfulness, mindful eating and self-reported serving size of energy dense foods among a sample of South Australian adults. Appetite, 67, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, S., Lau, M., Shapiro, S., Carlson, L., Anderson, N., Carmody, J., & Devins, G. (2004). Mindfulness: A proposed operational definition. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 11, 230–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, K., Ryan, R., & Creswell, J. (2007). Mindfulness: Theoretical foundations and evidence for its salutary effects. Psychological Inquiry, 18(4), 211–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T., Chorpita, B., Korotitsch, W., & Barlow, D. (1997). Psychometric properties of the depression anxiety stress scales (DASS) in clinical samples. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 35(1), 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos-Nonato, I., Galván-Valencia, O., Hernández-Barrera, L., Oviedo-Solís, C., & Barquera, S. (2023). Prevalencia de obesidad y factores de riesgo asociados en adultos mexicanos: Resultados de la Ensanut 2022. Salud Pública de México, 65(1), S238–S247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Celik-Erden, S., Karakus-Yilmaz, B., Kozaci, N., Uygur, A. B., Yigit, Y., Karakus, K., Aydin, I. E., Ersahin, T., & Ersahin, D. A. (2023). The relationship between depression, anxiety, and stress levels and eating behavior in emergency service workers. Cureus, 15(2), e35504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruz-Rodríguez, J., González-Vázquez, R., Reyes-Castillo, P., Mayorga-Reyes, L., Nájera-Medina, O., & Ramos-Ibáñez, N. (2019). Dietary intake and body composition associated with metabolic syndrome in university students. Mexican Journal of Eating Disorders, 10(1), 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dakanalis, A., Mentzelou, M., Papadopoulou, S. K., Papandreou, D., Spanoudaki, M., Vasios, G. K., Pavlidou, E., Mantzorou, M., & Giaginis, C. (2023). The association of emotional eating with overweight/obesity, depression, anxiety/stress, and dietary patterns: A review of the current clinical evidence. Nutrients, 15(5), 1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirbas, N., Kutlu, R., & Kurnaz, A. (2021). The relationship between mindful eating and body mass index and body compositions in adults. Annals of Nutrition and Metabolism, 77(5), 262–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denova-Gutiérrez, E., Ramírez-Silva, I., Rodríguez-Ramírez, S., JiménezAguilar, A., Shamah-Levy, T., & Rivera-Dommarco, J. A. (2016). Validity of a food frequency questionnaire to assess food intake in Mexican adolescent and adult population. Salud Pública de Mexico, 58(6), 617–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogan, B. G., & Tengilimoglu-Metin, M. M. (2023). Does mindful eating affect the diet quality of adults? Nutrition, 110, 112010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durán, S., Crovetto, M., Espinoza, V., Mena, F., Oñate, G., Fernández, M., Coñuecar, S., Guerra, A., & Valladares, M. (2017). Caracterización del estado nutricional, hábitos alimentarios y estilos de vida de estudiantes universitarios chilenos: Estudio multicéntrico. Revista Medica de Chile, 145(11), 1403–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Carrasco, M. P., & López-Ortiz, M. M. (2019). Relation between eating habits and risk of developing diabetes in Mexican university students. Nutrición Clínica y Dietetica Hospitalaria, 39(4), 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Framson, C., Kristal, A. R., Schenk, J., Littman, A., Zeliadt, S., & Benitez, D. (2009). Development and validation of the Mindful Eating Questionnaire. Journal of American Dietetic Association, 109(8), 1439–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulton, S., Décatirie-Spain, L., Fioramonto, X., Guiard, B., & Nakajima, S. (2021). The menace of obesity to depression and anxiety prevalence. Trends in Endocrinology & Metabolism, 33(1), 18–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, D., Heymsfield, S. B., Heo, M., Jebb, S. A., Murgatroyd, P. R., & Sakamoto, Y. (2000). Healthy percentage body fat ranges: An approach for developing guidelines based on body mass index. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 72(3), 694–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaona-Pineda, E. B., Rodríguez-Ramírez, S., Medina-Zacarías, M. C., Valenzuela-Bravo, D. G., Martínez-Tapia, B., & Arango-Angarita, A. (2023). Consumidores de grupos de alimentos en población mexicana. Ensanut Continua 2020–2022. Salud Pública de México, 65(Suppl. S1), S248–S258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giannopoulou, I., Kotopoulea-Nikolaidi, M., Daskou, S., Martyn, K., & Patel, A. (2020). Mindfulness in eating is inversely related to binge eating and mood disturbances in university students in health-related disciplines. Nutrients, 12(2), 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godfrey, K. M., Gallo, L. C., & Afari, N. (2015). Mindfulness-based interventions for binge eating: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 38(2), 348–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gradidge, P. J. L., & Cohen, E. (2018). Body mass index and associated lifestyle and eating behaviours of female students at a South African University. South African Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 31(4), 89–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurrola, G., Balcazar, P., Bonilla, M., & Virseda, J. (2006). Estructura factorial y consistencia interna de la escala de depresión ansiedad y estrés (DASS-21) en una muestra no clínica. Psicología y Ciencia Social, 8(2), 3–7. [Google Scholar]

- Hilger-Kolb, J., Loerbroks, A., & Diehl, K. (2017). Eating behaviour of university students in Germany: Dietary intake, barriers to healthy eating and changes in eating behaviour since the time of matriculation. Appetite, 109, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, D., Conner, M., Clancy, F., Moss, R., Wilding, S., & Bristow, M. (2022). Stress and eating behaviours in healthy adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Psychology Review, 16(2), 280–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinton, E. C., Beesley, V., Leary, S. D., & Ferriday, D. (2024). Associations between body mass index and episodic memory for recent eating, mindful eating, and cognitive distraction: A cross-sectional study. Obesity Science & Practice, 10(1), e728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, T., & Forestell, C. A. (2021). Mindfulness, depression, and emotional eating: The moderating role of nonjudging of inner experience. Appetite, 160, 105089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, C. H., Wang, W., Donatoni, L., & Meier, B. P. (2014). Mindful eating: Trait and state mindfulness predict healthier eating behavior. Personality and Individual Differences, 68, 107–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyte, R., Egan, H., & Mantzios, M. (2020). How does mindful eating without non-judgement, mindfulness and self-compassion relate to motivations to eat palatable foods in a student population? Nutrition and Health, 26(1), 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kheniser, K., Saxon, D. R., & Kashyap, S. R. (2021). Long-term weight loss strategies for obesity. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 106(7), 1854–1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K. S., Oh, H. J., Choi, Y. J., Huh, B. W., Kim, S. K., & Park, S. W. (2016). Reappraisal of waist circumference cutoff value according to general obesity. Nutrition & Metabolism, 13(1), 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konttinen, H., van Strien, T., Männistö, S., Jousilahti, P., & Haukkala, A. (2019). Depression, emotional eating and long-term weight changes: A population-based prospective study. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 16(1), 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyle, U. G., Bosaeus, I., De Lorenzo, A. D., Deurenberg, P., Elia, M., Gómez, J. M., & Pichard, C. (2004). Bioelectrical impedance analysis—Part I: Review of principles and methods. Clinical Nutrition, 23(5), 1226–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarevich, I., Irigoyen-Camacho, M. E., Velazquez-Alva, M. C., Lara-Flores, N., Nájera-Medina, O., & Zepeda-Zepeda, M. A. (2018). Depression and food consumption in Mexican college students. Nutricion Hospitalaria, 35(3), 252–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lingvay, I., Cohen, R. V., le Roux, C. W., & Sumothran, P. (2024). Obesity in adults. The Lancet, 404(10456), 972–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzini, R., Betancur-Ancona, D. A., Chel-Guerrero, L. A., Segura-Campos, M. R., & Castellanos-Ruelas, A. F. (2015). Estado nutricional en relación con el estilo de vida de estudiantes universitarios mexicanos. Nutricion Hospitalaria, 32(1), 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lovibond, P., & Lovibond, S. (1995). The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the tDepression, Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 33(3), 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Nieves, G., Sosa-Cordobés, E., Garrido-Fernández, A., Travé-González, G., & García-Padilla, F. M. (2019). Hábitos, preferencias y habilidades culinarias de estudiantes de primer curso de la Universidad de Huelva. Enfermería Global, 18(3), 127–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyzwinski, L. N., Caffery, L., Bambling, M., & Edirippulige, S. (2018). A systematic review of electronic mindfulness-based therapeutic interventions for weight, weight-related behaviors, and psychological stress. Telemedicine and e-Health, 24(3), 173–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mantzios, M., Egan, H., Bahia, H., Hussain, M., & Keyte, R. (2018a). How does grazing relate to body mass index, self-compassion, mindfulness and mindful eating in a student population? Health Psychology Open, 5(1), 2055102918762701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mantzios, M., Egan, H., Hussain, M., Keyte, R., & Bahia, H. (2018b). Mindfulness, self-compassion, and mindful eating in relation to fat and sugar consumption: An exploratory investigation. Eating and Weight Disorders-Studies of Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity, 23(6), 833–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantzios, M., & Wilson, C. (2015). Mindfulness, eating behaviors, and obesity: A review and reflection on current findings. Current Obesity Report, 4(1), 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, E., Epel, S., Aschbacher, K., Lustig, H., Acree, M., & Daubenmier, J. (2016). Reduced reward-driven eating accounts for the impact of a mindfulness-based diet and exercise intervention on weight loss: Data from the SHINE randomized controlled trial. Appetite, 100, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercado, D., Robinson, L., Gordon, G., Werthmann, J., Campbell, I. C., & Schmidt, U. (2021). The outcomes of mindfulness-based interventions for obesity and binge eating disorder: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Appetite, 166, 105464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metin, Z. E., Bayrak, N., Celik, O. M., & Akkoca, M. (2024). The relationship between emotional eating, mindful eating, and depression in young adults. Food Science & Nutrition, 13(1), e4028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moor, K. R., Scott, A. J., & McIntosh, W. D. (2013). Mindful eating and its relationship to body mass index and physical activity among university students. Mindfulness, 4, 269–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Rodríguez, J. R., Luna-Castro, J., Ballesteros-Yáñez, I., Pérez-Ortiz, J. M., Gómez-Romero, F. J., & Redondo-Calvo, F. J. (2021). Influence of biomedical education on health and eating habits of university students in Spain. Nutrition, 86, 111181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olatona, F. A., Onabanjo, O. O., Ugbaja, R. N., Nnoaham, K. E., & Adelejan, D. A. (2018). Dietary habits and metabolic risk factors for non-communicable diseases in a university undergraduate population. Journal of Health, Population and Nutrition, 37(21), 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olvera-Ruvalcaba, A. J., Gómez-Peresmitre, G., & Velasco-Rojano, E. (2019). Construction and validation of a mindful eating scale: A first approximation in the Mexican population. Mexican Journal of Eating Disorders, 10(2), 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omage, K., & Omuemu, V. O. (2018). Assessment of dietary pattern and nutritional status of undergraduate students in a private university in southern Nigeria. Food Science & Nutrition, 6(7), 1890–1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özkan, N., & Bilici, S. (2021). Are anthropometric measurements an indicator of intuitive and mindful eating? Eating and Weight Disorders. EWD, 26(2), 639–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paolassini-Guesnier, P., Van Beekum, M., Kesse-Guyot, E., Baudry, J., Bernard-Srour, B., Bellicha, A., & Péneau, S. (2025). Mindful eating is associated with a better diet quality in the NutriNet-Santé study. Appetite, 206, 107797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepe, R. B., Coelho, G. S. M. A., Miguel, F. D. S., Gualassi, A. C., Sarvas, M. M., Cercato, C., & de Melo, M. E. (2023). Mindful eating for weight loss in women with obesity: A randomized controlled trial. British Journal of Nutrition, 130(5), 911–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pintado-Cucarella, S., & Rodriguez-Salgado, P. (2016). Mindful eating and its relationship with body mass index, binge eating, anxiety, and negative affect. Journal of Behavior, Health & Social Issues, 8, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Fuentes, S., & Llorca, G. (2016). Mindful eating and eating styles in disorders of eating behavior. Agora de Salut, 3(36), 339–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sala, M., Ram, S. S., Vanzhula, I. A., & Levinson, C. A. (2020). Mindfulness and eating disorder psychopathology: A meta-analysis. Eating Disorders, 53(6), 834–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sala, M., Vanzhula, I., Roos, C. R., & Levinson, C. A. (2022). Mindfulness and eating disorders: A network analysis. Behavior Therapy, 5(2), 224–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shamah-Levy, T., Romero-Martínez, M., Barrientos-Gutiérrez, T., Cuevas-Nasu, L., Bautista-Arredondo, S., Colchero, M. A., & Rivera-Dommarco, J. (2022). Encuesta nacional de salud y nutrición 2021 sobre COVID-19. Instituto Nacional de Salud Pública. Available online: https://www.insp.mx/resources/images/stories/2022/docs/220801_Ensa21_digital_29julio.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Tanofsky-Kraff, M., & Yanovski, S. Z. (2004). Eating disorder or disordered eating? Non-normative eating patterns in obese individuals. Obesity Research, 12(9), 1361–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapper, K. (2022). Mindful eating: What we know so far. Nutrition Bulletin, 47(2), 168–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turgon, R., Ruffault, A., Juneau, C., Blatier, C., & Shankland, R. (2019). Eating disorder treatment: Systematic review and meta-analysis of the efficacy of mindfulness-based programs. Mindfulness, 10, 2225–2244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vittengl, J. R. (2018). Mediation of the bidirectional relations between obesity and depression among women. Psychiatry Research, 264, 254–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, M., Smith, N., & Ashwell, M. (2017). A structured literature review on the role of mindfulness, mindful eating and intuitive eating in changing eating behaviours: Effectiveness and associated potential mechanisms. Nutrition Research Reviews, 30(2), 272–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winkens, L. H. H., Elstgeest, L. E. M., van Strien, T., Penninx, B. W. J. H., Visser, M., & Brouwer, I. A. (2020). Does food intake mediate the association between mindful eating and change in depressive symptoms? Public Health Nutrition, 23(9), 1532–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkens, L. H. H., van Strien, T., Brouwer, I. A., Penninx, B. W. J. H., Visser, M., & Lähteenmäki, L. (2018). Associations of mindful eating domains with depressive symptoms and depression in three European countries. Journal of Affective Disorders, 1(228), 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2000). Physical status: The use of and interpretation of anthropometry, report of a WHO expert committee. WHO technical report series 894. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/37003 (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2024). Obesity and overweight. Available online: https://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight (accessed on 29 November 2024).

| Variable | Mean (± SD) or n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 21.95 ± 2.16 |

| Sex | |

| Female | 173 (77.23) |

| Male | 51 (22.77) |

| Body Mass Index (kg/m2) | |

| (mean ± SD) | 24.21 ± 3.88 |

| Normal (≥18.5 and <25) | 138 (61.61) |

| Overweight/obesity (≥25) | 86 (38.39) |

| Waist Circumference (cm) (cutoff values females ≥80, males ≥90) | |

| Normal | 148 (66.07) |

| High | 76 (33.93) |

| Body Fat (%) (cutoff values females ≥ 33, males ≥ 20) | |

| Normal | 108 (48.21) |

| High | 116 (51.79) |

| Mindful Eating Score (ME-11) (mean ± SD) | 26.71 ± 8.62 |

| Mindful Eating Score (excluding emotional eating items, ME-8) (mean ± SD) | 19.85 ± 7.03 |

| Emotional Distress (DASS-21) 1 (mean ± SD) | |

| Depression score | 16.27 ± 4.59 |

| Anxiety score | 17.65 ± 4.66 |

| Stress score | 14.21 ± 3.82 |

| Food Consumption | |

| Sweetened Beverages | |

| ≥2 times per week | 98 (43.75) |

| <2 times per week | 126 (56.25) |

| Sweetened Dairy Drinks | |

| ≥2 times per week | 61 (27.23) |

| <2 times per week | 163 (72.77) |

| Fried Foods | |

| ≥1 time per week | 173 (77.23) |

| <1 time per week | 51 (22.77) |

| Sweets and Desserts | |

| ≥1 time per week | 168 (75.00) |

| <1 time per week | 56 (25.00) |

| Sweetened Cereals | |

| ≥1 time per week | 60 (26.79) |

| <1 time per week | 164 (73.21) |

| Fast Food | |

| ≥1 time per week | 138 (61.61) |

| <1 time per week | 86 (38.39) |

| Mexican Snacks | |

| ≥1 time per week | 149 (66.52) |

| <1 time per week | 75 (33.48) |

| Processed Meat | |

| ≥1 time per week | 148 (66.07) |

| <1 time per week | 76 (33.93) |

| Alcohol | |

| ≥2 times per week | 80 (35.71) |

| <2 times per week | 144 (64.29) |

| (a) ME-11 | |||

| Outcome Variable | OR (95% CI) 1 | p | |

| Body Mass Index 3 | |||

| Mindful eating score (ME-11) 2 | 1.08 (1.04–1.12) | <0.001 | |

| Waist Circunference 4 | |||

| Mindful eating score (ME-11) 2 | 1.09 (1.04–1.13) | <0.001 | |

| Body Fat (%) 5 | |||

| Mindful eating score (ME-11) 2 | 1.06 (1.02–1.10) | <0.001 | |

| (b) ME-8 | |||

| Outcome Variable | OR (95% CI) 1 | p | |

| Body Mass Index 3 | |||

| Mindful eating score (ME-8) 2 | 1.10 (1.05–1.15) | <0.001 | |

| Waist Circunference 4 | |||

| Mindful eating score (ME-8) 2 | 1.11 (1.06–1.16) | <0.001 | |

| Body Fat (%) 5 | |||

| Mindful eating score (ME-8) 2 | 1.98 (1.03–1.13) | <0.001 | |

| (a) ME-11 | |||

| Outcome Variable | OR (95% CI) 1 | p | |

| Sweetened Beverages 3 | |||

| Mindful eating score (ME-11) 2 | 1.01 (0.98–1.05) | 0.468 | |

| Sweetened Dary Drinks 3 | |||

| Mindful eating score (ME-11) 2 | 1.02 (0.99–1.06) | 0.224 | |

| Fried Food 4 | |||

| Mindful eating score (ME-11) 2 | 1.06 (1.02–1.11) | 0.005 | |

| Sweets and Desserts 4 | |||

| Mindful eating score (ME-11) 2 | 1.07 (1.02–1.11) | 0.003 | |

| Sweetened Cereals 4 | |||

| Mindful eating score (ME-11) 2 | 1.01 (0.97–1.05) | 0.656 | |

| Fast Food 4 | |||

| Mindful eating score (ME-11) 2 | 1.05 (1.02–1.09) | 0.003 | |

| Mexican Snacks 4 | |||

| Mindful eating score (ME-11) 2 | 1.00 (0.97–1.04) | 0.867 | |

| Procesesed Meat 4 | |||

| Mindful eating score (ME-11) 2 | 1.00 (0.98–1.04) | 0.610 | |

| Alcohol 3 | |||

| Mindful eating score (ME-11) 2 | 1.03 (0.99–1.06) | 0.126 | |

| (b) ME-8 | |||

| Outcome Variable | OR (95% CI) 1 | p | |

| Sweetened Beverages 3 | |||

| Mindful eating score (ME-8) 2 | 1.01 (0.97–1.05) | 0.621 | |

| Sweetened Dary Drinks 3 | |||

| Mindful eating score (ME-8) 2 | 1.02 (0.97–1.06) | 0.457 | |

| Fried Food 4 | |||

| Mindful eating score (ME-8) 2 | 1.06 (1.01–1.11) | 0.024 | |

| Sweets and Desserts 4 | |||

| Mindful eating score (ME-8) 2 | 1.06 (1.01–1.12) | 0.026 | |

| Sweetened Cereals 4 | |||

| Mindful eating score (ME-8) 2 | 1.00 (0.96–1.05) | 0.974 | |

| Fast Food 4 | |||

| Mindful eating score (ME-8) 2 | 1.05 (1.01–1.10) | 0.020 | |

| Mexican Snacks 4 | |||

| Mindful eating score (ME-8) 2 | 1.00 (0.96–1.04) | 0.897 | |

| Procesesed Meat 4 | |||

| Mindful eating score (ME-8) 2 | 1.00 (0.97–1.04) | 0.938 | |

| Alcohol 3 | |||

| Mindful eating score (ME-11) 2 | 1.02 (0.98–1.06) | 0.429 | |

| (a) ME-11 | |||

| Mindful Eating, Including All Items of the Questionnaire (ME-11) 2 Outcome Variable | Predictor Variables | OR (95% CI) | p |

| Low Score (Tertile 1, reference) | |||

| Medium Score (Tertile 2) | Depression Score | 1.04 (0.97–1.12) | 0.253 |

| Age | 1.04 (0.94–1.15) | 0.466 | |

| Sex (Female = 1) | 1.51 (0.74–3.09) | 0.253 | |

| High Score (Tertile 3) | Depression Score | 1.14 (1.05–1.24) | <0.001 |

| Age | 1.03 (0.92–1.14) | 0.642 | |

| Sex (Female = 1) | 5.91 (2.22–15.73) | <0.001 | |

| Medium Score (Tertile 2) | Anxiety Score | 1.06 (0.99–1.14) | 0.112 |

| Age | 1.04 (0.94–1.16) | 0.425 | |

| Sex (Female = 1) | 1.49 (0.73–3.05) | 0.273 | |

| High Score (Tertile 3) | Anxiety Score | 1.19 (1.09–1.29) | <0.001 |

| Age | 1.04 (0.93–1.16) | 0.488 | |

| Sex (Female = 1) | 5.89 (2.17–15.97) | <0.001 | |

| Medium Score (Tertile 2) | Stress Score | 1.06 (0.98–1.16) | 0.150 |

| Age | 1.04 (0.94–1.15) | 0.473 | |

| Sex (Female = 1) | 1.44 (0.71–2.95) | 0.315 | |

| High Score (Tertile 3) | Stress Score | 1.15 (1.05–1.27) | 0.003 |

| Age | 1.03 (0.92–1.14) | 0.631 | |

| Sex (Female = 1) | 5.24 (1.98–13.86) | <0.001 | |

| (b) ME-8 | |||

| Mindful Eating Score, Excluding Emotional Eating Items of the Questionnaire (ME-8) 2 Outcome Variable | Predictor Variable | OR (95% CI) | p |

| Low Score (Tertile 1, reference) | |||

| Medium Score (Tertile 2) | Depression Score | 1.06 (0.99–1.14) | 0.078 |

| Age | 1.07 (0.96–1.19) | 0.241 | |

| Sex (Female = 1) | 2.51 (1.21–5.22) | 0.014 | |

| High Score (Tertile 3) | Depression Score | 1.11 (1.02–1.20) | 0.011 |

| Age | 1.04 (0.93–1.17) | 0.490 | |

| Sex (Female = 1) | 5.90 (2.24–15.54) | <0.001 | |

| Medium Score (Tertile 2) | Anxiety Score | 1.08 (1.01–1.16) | 0.026 |

| Age | 1.07 (0.96–1.20) | 0.207 | |

| Sex (Female = 1) | 2.45 (1.18–5.12) | 0.017 | |

| High Score (Tertile 3) | Anxiety Score | 1.13 (1.05–1.23) | 0.002 |

| Age | 1.05 (0.93–1.18) | 0.404 | |

| Sex (Female = 1) | 5.74 (2.17–15.22) | <0.001 | |

| Medium Score (Tertile 2) | Stress Score | 1.10 (1.01–1.20) | 0.031 |

| Age | 1.07 (0.96–1.19) | 0.243 | |

| Sex (Female = 1) | 2.35 (1.13–4.90) | 0.023 | |

| High Score (Tertile 3) | Stress Score | 1.12 (1.02–1.23) | 0.017 |

| Age | 1.04 (0.93–1.17) | 0.494 | |

| Sex (Female = 1) | 5.40 (2.24–15.54) | <0.001 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lazarevich, I.; Irigoyen-Camacho, M.E.; Radilla-Vázquez, C.C.; Gutiérrez-Tolentino, R.; Velazquez-Alva, M.C.; Zepeda-Zepeda, M.A. Mindful Eating and Its Relationship with Obesity, Eating Habits, and Emotional Distress in Mexican College Students. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 669. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15050669

Lazarevich I, Irigoyen-Camacho ME, Radilla-Vázquez CC, Gutiérrez-Tolentino R, Velazquez-Alva MC, Zepeda-Zepeda MA. Mindful Eating and Its Relationship with Obesity, Eating Habits, and Emotional Distress in Mexican College Students. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(5):669. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15050669

Chicago/Turabian StyleLazarevich, Irina, María Esther Irigoyen-Camacho, Claudia Cecilia Radilla-Vázquez, Rey Gutiérrez-Tolentino, Maria Consuelo Velazquez-Alva, and Marco Antonio Zepeda-Zepeda. 2025. "Mindful Eating and Its Relationship with Obesity, Eating Habits, and Emotional Distress in Mexican College Students" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 5: 669. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15050669

APA StyleLazarevich, I., Irigoyen-Camacho, M. E., Radilla-Vázquez, C. C., Gutiérrez-Tolentino, R., Velazquez-Alva, M. C., & Zepeda-Zepeda, M. A. (2025). Mindful Eating and Its Relationship with Obesity, Eating Habits, and Emotional Distress in Mexican College Students. Behavioral Sciences, 15(5), 669. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15050669