How Does Nature Connectedness Improve Mental Health in College Students? A Study of Chain Mediating Effects

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. The Correlation Between Nature Connectedness and the College Students’ Mental Health

1.2. The Meditating Role of Resilience

1.3. The Role of Meaning in Life as a Mediator

1.4. The Chained Mediating Effect of Resilience and Meaning in Life

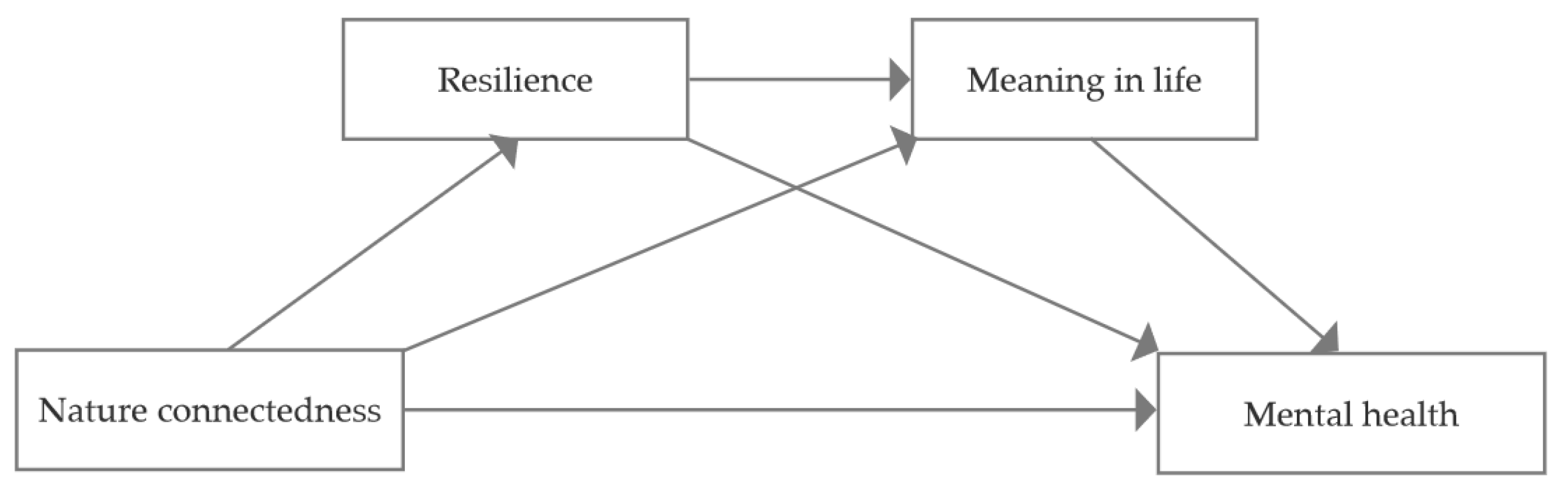

1.5. The Current Study

2. Methods

2.1. Procedure

2.2. Participants

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. General Investigation

2.3.2. Connectedness to Nature Scale (CNS)

2.3.3. The Brief Version of the Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC-10)

2.3.4. The Meaning in Life Questionnaire—Chinese Version (MLQ-C)

2.3.5. Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale (DASS-21)

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. The Control Process for Common Method Deviation

3.2. Descriptive Statistical Data and Correlation Analysis

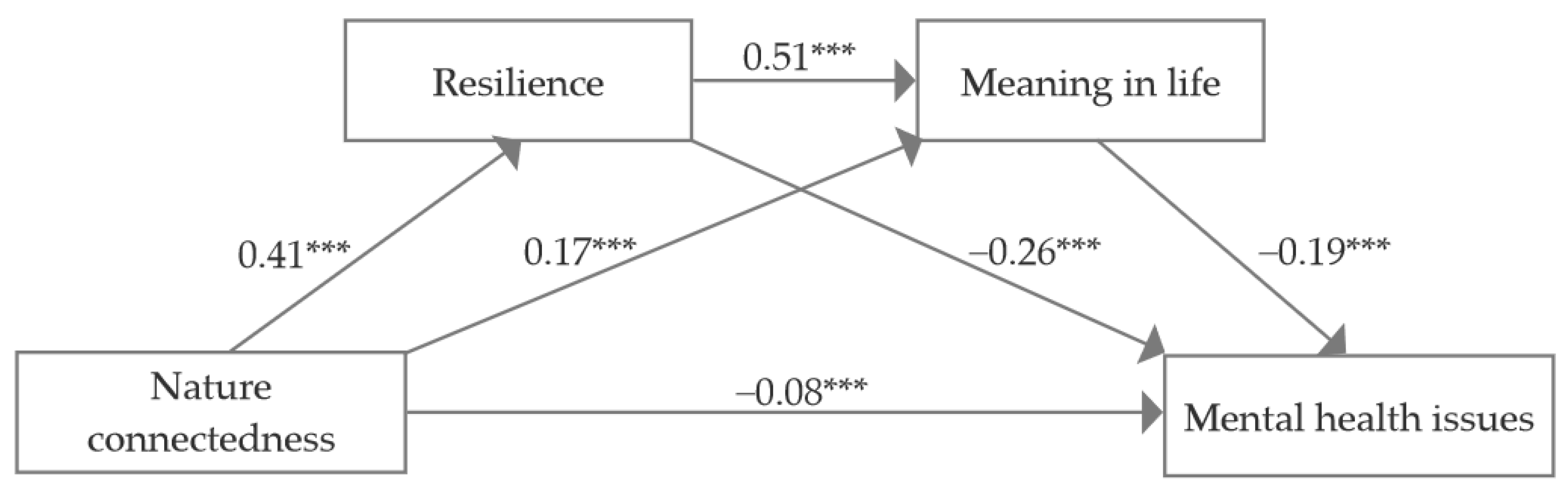

3.3. The Significance Examination of the Mediating Effect

4. Discussion

4.1. How Nature Connectedness Directly Influences the Mental Health of College Students

4.2. How Resilience and Meaning in Life Act as Mediators

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions and Future Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alvarsson, J. J., Wiens, S., & Nilsson, M. E. (2010). Stress recovery during exposure to nature sound and environmental noise. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 7(3), 1036–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American College Health Association. (2020). American college health association-national college health assessment III: Reference group executive summary fall 2020. American College Health Association, 1(1), 1. [Google Scholar]

- Arnett, J. J. (2007). Emerging adulthood: What is it, and what is it good for? Child Development Perspectives, 1(2), 68–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benessaiah, K., & Chan, K. M. (2023). Why reconnect to nature in times of crisis? Ecosystem contributions to the resilience and well-being of people going back to the land in Greece. People and Nature, 5(6), 2026–2047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratman, G. N., Hamilton, J. P., & Daily, G. C. (2012). The impacts of nature experience on human cognitive function and mental health. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1249(1), 118–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brockner, J., Higgins, E. T., & Low, M. B. (2004). Regulatory focus theory and the entrepreneurial process. Journal of Business Venturing, 19(2), 203–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capaldi, C. A., Dopko, R. L., & Zelenski, J. M. (2014). The relationship between nature connectedness and happiness: A meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M., Huang, S. H., Xu, N., Li, J. J., & Wu, Q. L. (2023). Effect between trait anxiety and excessive WeChat use in college students: The chain mediating role of cognitive reappraisal and meaning in life. China Journal of Health Psychology, 31(2), 249–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W., Yang, T., Gao, R. F., Liang, Y. X., & Meng, Q. F. (2021). Psychometric properties and measurement invariance across gender of brief version of connor-davidson resilience scale in Chinese college students. Journal of Southwest China Normal University (Natural Science Edition), 46(11), 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y. L., & Li, J. F. (2024). Does travel bring meaning in life? Study on the meaning-making process in tourism context. Tourism Tribune, 39, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- China Youth Daily Press, China Youth Media for Universities & DingXiangDoctor. (2020). 2020 China college students’ health survey report. Available online: https://tech.sina.com.cn/roll/2020-03-11/doc-iimxxstf8020854.shtml (accessed on 25 October 2024).

- Chung, J., Lam, K., Ho, K., Cheung, A., Ho, L., Gibson, F., & Li, W. (2018). Relationships among resilience, self-esteem, and depressive symptoms in Chinese adolescents. Journal of Health Psychology, 25(13–14), 2396–2405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Connor, K. M., & Davidson, J. R. T. (2003). Development of a new resilience scale: The Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC). Depression and Anxiety, 18(2), 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, J. R., & Henry, J. D. (2003). The Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS): Normative data and latent structure in a large non-clinical sample. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 42(2), 111–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronon, W. (1996). The Trouble with wilderness: Or, getting back to the wrong nature. Environmental History, 1(1), 7–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowe, E., & Higgins, E. T. (1997). Regulatory focus and strategic inclinations: Promotion and prevention in decision-making. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 69(2), 117–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E., Suh, E. M., Lucas, R. E., & Smith, H. L. (1999). Subjective well-being: Three decades of progress. Psychological Bulletin, 125(2), 276–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y. M., & Xie, Y. J. (2019). Embodiment paradigm of tourist experience research. Tourism Tribune, 34(11), 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankl, V. E. (1971). Man’s search for meaning: An introduction to logotherapy. Frontiers Media SA. [Google Scholar]

- Frantz, C. M., & Mayer, F. S. (2014). The importance of connection to nature in assessing environmental education programs. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 41, 85–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, B. L. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology. American Psychologist, 56(3), 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, R. A., Irvine, K. N., Devine-Wright, P., Warren, P. H., & Gaston, K. J. (2007). Psychological benefits of greenspace increase with biodiversity. Biology Letters, 3(4), 390–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, X., Xie, X. Y., Xu, R., & Luo, Y. J. (2010). Psychometric properties of the Chinese versions of DASS-21 in Chinese college students. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 18(4), 443–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halama, P., & Dedova, M. (2007). Meaning in life and hope as predictors of positive mental health: Do they explain residual variance not predicted by personality traits? Studia Psychologica, 49(3), 191–200. [Google Scholar]

- Heine, S. J., Proulx, T., & Vohs, K. D. (2006). The meaning maintenance model: On the coherence of social motivations. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 10(2), 88–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heintzelman, S. J., & King, L. A. (2019). Routines and meaning in life. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 45(5), 688–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heisel, M. J., & Flett, G. L. (2004). Purpose in life, satisfaction with life, and suicide ideation in a clinical sample. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 26(2), 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinds, J., & Sparks, P. (2011). The affective quality of human-natural environment relationships. Evolutionary Psychology, 9(3), 451–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, A. J., Passmore, H.-A., & Buro, K. (2013). Meaning in nature: Meaning in life as a mediator of the relationship between nature connectedness and well-being. Journal of Happiness Studies, 14(6), 1681–1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M. H., Chen, X., & Zhang, X. W. (2020). Relationship between resilience and meaning in life: Mediating effect of perceived social support. China Journal of Health Psychology, 28(5), 776–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, T., Zhang, D., & Wang, J.-L. (2015). A meta-analysis of the trait resilience and mental health. Personality and Individual Differences, 76, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q. Y., Bai, K., & Du, T. (2022). Everyday life of tourism destination and its therapeutic meaning: A case study of the old town of Lijiang. Tourism Tribune, 37(2), 14–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institute of Psychology, Chinese Academy of Sciences. (2023). The 2022 “blue book on mental health”: Report on the development of national mental health in China (2021–2022). Available online: http://psy.china.com.cn/node_1013711.htm (accessed on 25 October 2024).

- Jia, L. X., & Wang, B. J. (2018). The relationship between optimistic intelligence quotient and life satisfaction of college students: The mediating role of resilience. Studies of Psychology and Behavior, 16(1), 88–95. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, X. M., Chen, M. N., Zhou, C. J., Chen, X. S., Shen, Q., Ma, Y. H., & Wang, C. R. (2020). Influence of novel coronavirus pneumonia on coping style and resilience level of patients. Psychologies Magazine, 15(18), 38–39+42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joschko, L., Pálsdóttir, A. M., Grahn, P., & Hinse, M. (2023). Nature-based therapy in individuals with mental health disorders, with a focus on mental well-being and connectedness to nature—A pilot study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20, 2167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalisch, R., Baker, D. G., Basten, U., Boks, M. P., Bonanno, G. A., Brummelman, E., Chmitorz, A., Fernàndez, G., Fiebach, C. J., Galatzer-Levy, I., Geuze, E., Groppa, S., Helmreich, I., Hendler, T., Hermans, E. J., Jovanovic, T., Kubiak, T., Lieb, K., Lutz, B., … Kleim, B. (2017). The resilience framework as a strategy to combat stress-related disorders. Nature Human Behaviour, 1(11), 784–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamitsis, I., & Francis, A. J. P. (2013). Spirituality mediates the relationship between engagement with nature and psychological wellbeing. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 36, 136–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, S. (1989). The experience of nature: A psychological perspective. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, S. (1995). The restorative benefits of nature: Toward an integrative framework. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 15(3), 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karataş, Z., & Tagay, Ö. (2021). The relationships between resilience of the adults affected by the covid pandemic in Turkey and Covid-19 fear, meaning in life, life satisfaction, intolerance of uncertainty and hope. Personality and Individual Differences, 172, 110592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellert, S. R., & Wilson, E. O. (1995). The biophilia hypothesis. Island Press. [Google Scholar]

- King, L. A., & Hicks, J. A. (2021). The science of meaning in life. Annual Review of Psychology, 72(1), 561–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, N. M., Stillman, T. F., Hicks, J. A., Kamble, S., Baumeister, R. F., & Fincham, F. D. (2013). To belong is to matter: Sense of belonging enhances meaning in life. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 39(11), 1418–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasota, A., & Mróz, J. (2021). Positive psychology in times of pandemic—Time perspective as a moderator of the relationship between resilience and meaning in life. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(24), 13340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lent, R. W. (2004). Toward a unifying theoretical and practical perspective on well-being and psychosocial adjustment. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 51(4), 482–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C., Xu, Y. C., Zhang, Z., Li, S. J., & Duan, S. L. (2023). The role of mindfulness cultivation in relieving negative emotions of college students: The mediating effect of psychological resilience. Psychologies Magazine, 18(18), 57–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N., & Wu, J. P. (2016a). The effect of natural connectedness on subjective well-being of college students: The mediating role of mindfulness. Psychology: Techniques and Applications, 4(5), 273–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N., & Wu, J. P. (2016b). Revise of the connectedness to nature scale and its reliability and validity. China Journal of Health Psychology, 24(9), 1347–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S. J. (2024). The current situation and influencing factors of colleges and universities students’ sense of meaning in life. West Journal, 7, 154–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y. M., Li, J., & Wu, F. H. (2018). Connectedness to nature: Conceptualization, measurements and promotion. Psychological Development and Education, 34(1), 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L. N., Liu, M., Kuang, J. W., Zhu, H. Q., & Nan, J. (2021). Negative life events and depression in college students: Chain mediating effect. China Journal of Health Psychology, 29(6), 932–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louv, R. (2008). Last child in the woods: Saving our children from nature-deficit disorder. Algonquin Books. [Google Scholar]

- Luthar, S. S., Cicchetti, D., & Becker, B. (2000). The construct of resilience: A critical evaluation and guidelines for future work. Child Development, 71(3), 543–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lydia, L., & Jim, J. (2005). Schizophrenia and urbanicity: A major environmental influence—Conditional on genetic risk. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 31(4), 795–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machell, K. A., Kashdan, T. B., Short, J. L., & Nezlek, J. B. (2015). Relationships between meaning in life, social and achievement events, and positive and negative affect in daily life. Journal of Personality, 83(3), 287–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masten, A. S. (2014). Global perspectives on resilience in children and youth. Child Development, 85(1), 6–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masten, A. S., & Wright, M. O. (2009). Resilience over the lifespan: Developmental perspectives on resistance, recovery, and transformation. In Handbook of adult resilience (pp. 213–237). The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, F. S., & Frantz, C. M. (2004). The connectedness to nature scale: A measure of individuals’ feeling in community with nature. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 24(4), 503–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, F. S., Frantz, C. M., Bruehlman-Senecal, E., & Dolliver, K. (2009). Why is nature beneficial?: The role of connectedness to nature. Environment and Behavior, 41(5), 607–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X. Z. (2024). The relationship between defensive pessimism and mental health in junior high school students: The chain mediating role of self-worth and positive coping styles [Master’s Thesis, Hebei University]. [Google Scholar]

- Michalos, A. C. (Ed.). (2014). Encyclopedia of quality of life and well-being research. Springer Netherlands. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, H. Y., & Gan, Y. Q. (2017). Relationship between self-concept clarity and meaning in life and subjective well-being. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 25(5), 923–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisbet, E. K., & Zelenski, J. M. (2011). Underestimating nearby nature: Affective forecasting errors obscure the happy path to sustainability. Psychological Science, 22(9), 1101–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisbet, E. K., Zelenski, J. M., & Murphy, S. A. (2009). The nature relatedness scale: Linking individuals’ connection with nature to environmental concern and behavior. Environment and Behavior, 41(5), 715–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisbet, E. K., Zelenski, J. M., & Murphy, S. A. (2011). Happiness is in our nature: Exploring nature relatedness as a contributor to subjective well-being. Journal of Happiness Studies, 12(2), 303–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passmore, H.-A., & Howell, A. J. (2014). Eco-existential positive psychology: Experiences in nature, existential anxieties, and well-being. The Humanistic Psychologist, 42(4), 370–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H. S., Li, C., Zhong, S. N., & Zhang, J. H. (2023). Literature review on human-nature relationships: Nature contact, nature connectedness and nature benefits. Geographical Research, 42(4), 1101–1116. [Google Scholar]

- Poon, K.-T., Teng, F., Chow, J. T., & Chen, Z. (2015). Desiring to connect to nature: The effect of ostracism on ecological behavior. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 42, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pritchard, A., Richardson, M., Sheffield, D., & McEwan, K. (2020). The relationship between nature connectedness and eudaimonic well-being: A meta-analysis. Journal of Happiness Studies, 21(3), 1145–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruchno, R., Heid, A. R., & Genderson, M. W. (2015). Resilience and successful aging: Aligning complementary constructs using a life course approach. Psychological Inquiry, 26(2), 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, M., Hallam, J., & Lumber, R. (2015). One thousand good things in nature: Aspects of nearby nature associated with improved connection to nature. Environmental Values, 24(5), 603–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R. M., Weinstein, N., Bernstein, J., Brown, K. W., Mistretta, L., & Gagné, M. (2010). Vitalizing effects of being outdoors and in nature. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 30(2), 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C. D., Singer, B., Love, G. D., & Essex, E. (1998). Resilience in adulthood and later life: Defining features and dynamic processes. In Handbook of aging and mental health: An integrative approach (pp. 69–96). Plenum Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schultz, P. (1999). New environmental theories: Empathizing with nature: The effects of perspective taking on concern for environmental issues. Journal of Social Issues, 56, 391–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C., Ikei, H., & Miyazaki, Y. (2016). Physiological effects of nature therapy: A review of the research in Japan. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 13, 781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steger, M. F. (2012). Making meaning in life. Psychological Inquiry, 23(4), 381–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steger, M. F., Frazier, P., Oishi, S., & Kaler, M. (2006). The meaning in life questionnaire: Assessing the presence of and search for meaning in life. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 53(1), 80–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steger, M. F., Kashdan, T. B., Sullivan, B. A., & Lorentz, D. (2008). Understanding the search for meaning in life: Personality, cognitive style, and the dynamic between seeking and experiencing meaning. Journal of Personality, 76(2), 199–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steidle, A., & Werth, L. (2014). In the spotlight: Brightness increases self-awareness and reflective self-regulation. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 39, 40–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D. K., Yu, R. Y., Lv, L., & Liao, C. J. (2021). On impact and protective factors of college students’ anxiety under background of major emergency epidemic crisis. Journal of Southwest China Normal University (Natural Science Edition), 46(10), 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H. L. (2022). Family cohesion and self-esteem: The mediating effect of meaning in life. China Journal of Health Psychology, 30(4), 626–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takayama, N., Saito, K., Fujiwara, A., & Tsutsui, S. (2017). Influence of five-day suburban forest stay on stress coping, resilience, and mood states. Journal of Environmental Information Science, 2, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, D. D., & Wen, Z. L. (2020). Statistical approaches for testing common method bias: Problems and suggestions. Journal of Psychological Science, 43(1), 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, P. M., Klotz, A., McClean, S., & Lee, R. (2023). From natural to novel: The cognition-broadening effects of contact with nature at work on creativity. Journal of Management, 014920632311721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, W., Wang, Z. X., & Zhu, H. (2015). The body, the view of body, and the study of body in human geography. Geographical Research, 34(6), 1173–1187. [Google Scholar]

- Ulrich, R., Simons, R., Losito, B., Fiorito, E., Miles, M., & Zelson, M. (1991). Stress recovery during exposure to natural and urban environments. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 11, 201–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, R. S. (1983). Aesthetic and affective response to natural environment. In I. Altman, & J. F. Wohlwill (Eds.), Behavior and the Natural Environment (pp. 85–125). Springer US. [Google Scholar]

- Verkuyten, M. (1998). Perceived discrimination and self-esteem among ethnic minority adolescents. The Journal of Social Psychology, 138(4), 479–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vining, J., Merrick, M., & Price, E. (2008). The distinction between humans and nature: Human perceptions of connectedness to nature and elements of the natural and unnatural. Human Ecology Review, 15(1), 11. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C. Y., Ji, S. H., & Chen, X. (2020). The relationship between nature connectedness and college students’ experience of life meaning: The mediating role of nature appreciation. Journal of Xinyang Normal University (Philosophy and Social Sciences Edition), 40(5), 45–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C. Y., & Lei, P. (2018). The influence of nature connectedness on college students’ depression: The mediation of loneliness and self-esteem. Heilongjiang Researches on Higher Education, 2, 89–93. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W., & Ma, W. (2021). Construction of a meaning effectiveness model: A new interpretation of meaning in life. New Ideas in Psychology, 63, 100876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X. Q., You, Y. Y., & Zhang, D. J. (2016). Psychometric properties of Meaning in Life Questionnaire Chinese version (MLQ-C) in Chinese university students and its relations with psychological quality. Journal of Southwest University (Natural Science Edition), 38(10), 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, E. E. (1995). Resilience in development. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 4(3), 81–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, M. P., Elliott, L. R., Grellier, J., Economou, T., Bell, S., Bratman, G. N., Cirach, M., Gascon, M., Lima, M. L., Lohmus, M., Nieuwenhuijsen, M., Ojala, A., Roiko, A., Schultz, P. W., van den Bosch, M., & Fleming, L. E. (2021). Associations between green/blue spaces and mental health across 18 countries. Scientific Reports, 11, 8903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, E. O. (1984). Biophilia: The human bond with other species. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, P. T. P. (2009). Positive existential psychology. In S. Lopez (Ed.), Encyclopedia of positive psychology (pp. 345–351). Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, C. Z., Huang, T. T., Wang, T., Yu, L. X., & Sun, Q. W. (2022). Effect of basic psychological needs satisfaction on suicidal ideation: The mediating role of life responsibility and the moderating role of differentiation of self. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 30(4), 949–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C. Z., Rong, S., Zhu, F. T., Chen, Y., & Guo, Y. Y. (2018). Basic psychological need and its satisfaction. Advances in Psychological Science, 26(6), 1063–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y., Geng, L., Xiang, P., Zhang, J., & Zhu, L. (2017). Nature connectedness: It’s concept, measurement, function and intervention. Advances in Psychological Science, 25(8), 1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y., Wang, L., Passmore, H.-A., Zhang, J., Zhu, L., & Cai, H. (2021). Viewing nature scenes reduces the pain of social ostracism. The Journal of Social Psychology, 161(2), 197–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, H. S., & Su, J. J. (2024). Mental health education from the perspective of embodied cognition. Moral Education China, 16, 15–25. [Google Scholar]

- Yıldırım, M., Arslan, G., & Ahmad Aziz, I. (2020). Why do people high in COVID-19 worry have more mental health disorders? The roles of resilience and meaning in life. Psychiatria Danubina, 32(3), 505–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B., Wang, A., Ye, Y., Liu, J., & Lin, L. (2024). The relationship between meaning in life and mental health in chinese undergraduates: The mediating roles of self-esteem and interpersonal trust. Behavioral Sciences, 14(8), 720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J. W., Howell, R. T., & Iyer, R. (2014). Engagement with natural beauty moderates the positive relation between connectedness with nature and psychological well-being. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 38, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L., Wu, Y. T. N., Ji, T. L., & Jia, Y. R. (2022). Effects of connectedness to nature and place attachment on pro-environmental behavior in adolescents: The mediating role of environmental concern. Journal of Hangzhou Normal University (Natural Science Edition), 21(1), 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P., Peng, L., Xu, C., Zhang, W. M., Liu, Y., & Li, M. (2024). Effect of group psychological training based on gratitude and resilience on sense of meaning in life and psychological well-being among college students. Army Medical Journal, 46(9), 969–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S. Y., Xu, Y., & Yang, H. K. (2010). The connotation, measurement and function of meaning in life. Advances in Psychological Science, 18(11), 1756–1761. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W. J., Jin, Y., & Wang, C. Y. (2020). The relationship among college students’ emotional regulation self-efficacy, psychological resilience and coping styles. Journal of Huaibei Normal University (Philosophy and Social Sciences), 41(5), 102–107. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, L. M., Zhang, H. B., & Sun, J. H. (2015). Factors affecting low-carbon tourism behavior under tourist situations in Sanya. Resources Science, 37(1), 201–210. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, S. N., Huang, P. H., Peng, H. S., Xu, C. X., & Yan, B. J. (2020). An exploratory case study on children’s cognition of tourism. Tourism Tribune, 35(2), 38–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L. J., Yang, Q., Ye, B. J., Chen, Z. N., & Zhang, L. (2022). Connectedness to nature on college students’ depression: A moderated mediation model. Psychological Development and Education, 38(6), 886–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Number (n) | Percentage (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 375 | 53.34% |

| Female | 328 | 46.66% | |

| Grade | Freshmen | 235 | 33.43% |

| Sophomores | 243 | 34.57% | |

| Juniors | 101 | 14.37% | |

| Seniors | 89 | 12.66% | |

| Graduate students | 35 | 4.98% | |

| Home locality | Urban | 325 | 46.23% |

| Rural | 378 | 53.77% | |

| Student leader | Yes | 306 | 43.53% |

| No | 397 | 56.47% | |

| Family | Only child | 262 | 37.27% |

| Have siblings | 441 | 62.73% | |

| Variable | M ± SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Nature connectedness | 52.98 ± 7.78 | 1 | |||

| 2. Resilience | 24.72 ± 6.60 | 0.389 ** | 1 | ||

| 3. Meaning in life | 48.25 ± 8.92 | 0.402 ** | 0.579 ** | 1 | |

| 4. Mental health issues | 19.77 ± 13.41 | −0.349 ** | −0.401 ** | −0.434 ** | 1 |

| Regression Equation | Overall Fit Index | Significance of the Regression Coefficient | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome Variable | Predictor Variable | R | R2 | F | β | SE | t |

| Mental health issues | Nature connectedness | 0.50 | 0.25 | 37.68 *** | −0.26 | 0.03 | −7.46 *** |

| Resilience | Nature connectedness | 0.40 | 0.16 | 22.65 *** | 0.41 | 0.04 | 11.32 *** |

| Meaning in life | Nature connectedness | 0.63 | 0.40 | 65.23 *** | 0.17 | 0.03 | 5.00 *** |

| resilience | 0.51 | 0.03 | 15.86 *** | ||||

| Mental health issues | Nature connectedness | 0.61 | 0.38 | 52.18 *** | −0.08 | 0.04 | −2.23 * |

| Resilience | −0.26 | 0.04 | −6.67 *** | ||||

| Meaning in life | −0.19 | 0.04 | −5.11 *** | ||||

| Route | Effect Value | Standard Error | Boot LLCI | Boot ULCI | Effect Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nature connectedness → Resilience → Mental health issues | −0.11 | 0.02 | −0.15 | −0.07 | 42.31% |

| Nature connectedness → Meaning in life → Mental health issues | −0.03 | 0.01 | −0.06 | −0.01 | 11.54% |

| Nature connectedness → Resilience → Meaning in life → Mental health issues | −0.04 | 0.01 | −0.06 | −0.02 | 15.38% |

| Direct effect | −0.08 | 0.04 | −0.15 | −0.01 | 30.77% |

| Total indirect effect | −0.18 | 0.02 | −0.23 | −0.14 | 69.23% |

| Total effect | −0.26 | 0.03 | −0.33 | −0.19 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ma, C.; Zhao, M.; Zhang, Y. How Does Nature Connectedness Improve Mental Health in College Students? A Study of Chain Mediating Effects. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 654. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15050654

Ma C, Zhao M, Zhang Y. How Does Nature Connectedness Improve Mental Health in College Students? A Study of Chain Mediating Effects. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(5):654. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15050654

Chicago/Turabian StyleMa, Chong, Mei Zhao, and Yuqing Zhang. 2025. "How Does Nature Connectedness Improve Mental Health in College Students? A Study of Chain Mediating Effects" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 5: 654. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15050654

APA StyleMa, C., Zhao, M., & Zhang, Y. (2025). How Does Nature Connectedness Improve Mental Health in College Students? A Study of Chain Mediating Effects. Behavioral Sciences, 15(5), 654. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15050654