How Empowering Leadership Drives Proactivity in the Chinese IT Industry: Mediation Through Team Job Crafting and Psychological Safety with ICT Knowledge as a Moderator

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Foundation and Hypotheses Development

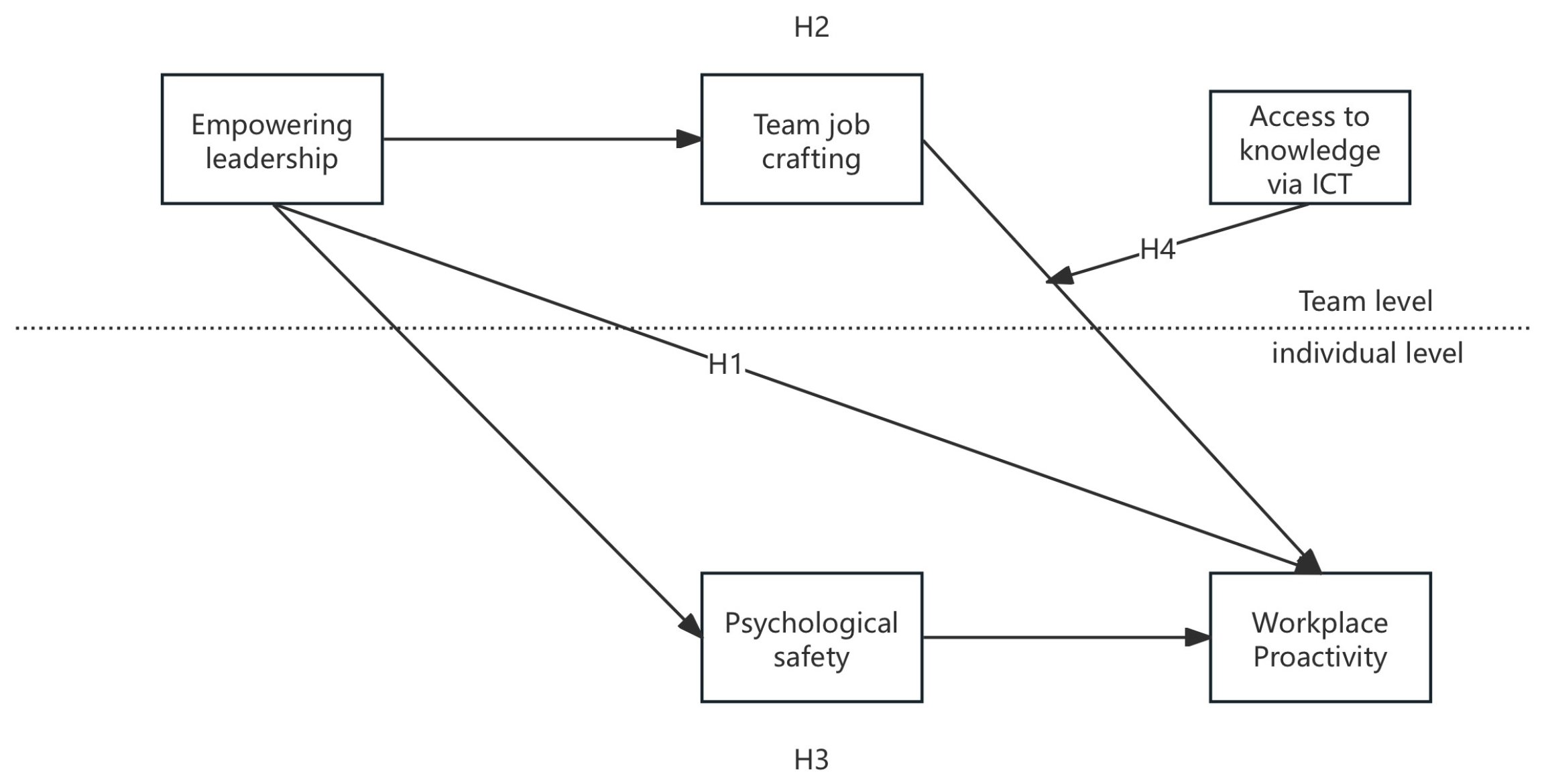

2.1. Empowering Leadership and Workplace Proactivity

2.2. Mediating Role of Team Job Crafting Between Empowering Leadership and Workplace Proactivity

2.3. Mediating Role of Psychological Safety Between Empowering Leadership and Workplace Proactivity

2.4. Moderating Effect of Access to Knowledge via ICT on the Relationship Between Team Job Crafting and Workplace Proactivity

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Sample and Procedure

3.2. Measures

3.3. Analytic Strategy

4. Data Analysis and Results

4.1. Preliminary Analyses

4.2. Hypothesis Tests

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

6. Limitations and Future Research Direction

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ahearne, M., Mathieu, J., & Rapp, A. (2005). To empower or not to empower your sales force? An empirical examination of the influence of leadership empowerment behavior on customer satisfaction and performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(5), 945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, I., Gao, Y., Su, F., & Khan, M. K. (2023). Linking ethical leadership to followers’ innovative work behavior in Pakistan: The vital roles of psychological safety and proactive personality. European Journal of Innovation Management, 26(3), 755–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N., Ullah, Z., AlDhaen, E., Han, H., & Scholz, M. (2022). A CSR perspective to foster employee creativity in the banking sector: The role of work engagement and psychological safety. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 67, 102968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M. A., & Khalid, S. (2019). Empowering leadership and proactive behavior: Mediating role of psychological empowerment and moderating role of leader-follower distance. Abasyn University Journal of Social Sciences, 12(1), 50–61. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Ansi, A., Garad, A., & Al-Ansi, A. (2021). ICT-based learning during COVID-19 outbreak: Advantages, opportunities and challenges. Gagasan Pendidikan Indonesia, 2(1), 10–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amundsen, S., & Martinsen, Ø. L. (2014). Empowering leadership: Construct clarification, conceptualization, and validation of a new scale. The Leadership Quarterly, 25(3), 487–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arefin, M. S., Arif, I., & Raquib, M. (2015). High-performance work systems and proactive behavior: The mediating role of psychological empowerment. International Journal of Business and Management, 10(3), 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A. B., Tims, M., & Derks, D. (2012). Proactive personality and job performance: The role of job crafting and work engagement. Human Relations, 65(10), 1359–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binyamin, G., & Brender-Ilan, Y. (2018). Leaders’s language and employee proactivity: Enhancing psychological meaningfulness and vitality. European Management Journal, 36(4), 463–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryk, A. S., & Raudenbush, S. W. (1992). Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods. Sage Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- CAICT. (2023). China digital workforce white paper. China Academy of Information and Communications Technology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Carmeli, A., Brueller, D., & Dutton, J. E. (2009). Learning behaviours in the workplace: The role of high-quality interpersonal relationships and psychological safety. Systems Research and Behavioral Science: The Official Journal of the International Federation for Systems Research, 26(1), 81–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmeli, A., Reiter-Palmon, R., & Ziv, E. (2010). Inclusive leadership and employee involvement in creative tasks in the workplace: The mediating role of psychological safety. Creativity Research Journal, 22(3), 250–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascio, W. F., & Montealegre, R. (2016). How technology is changing work and organizations. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 3(1), 349–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S. (2019, April 29). The new form of digital labor. The Paper. Available online: https://www.thepaper.cn/newsDetail_forward_3291793 (accessed on 12 April 2025).

- Choi, S. B., Ullah, S. E., & Kang, S.-W. (2021). Proactive personality and creative performance: Mediating roles of creative self-efficacy and moderated mediation role of psychological safety. Sustainability, 13(22), 12517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coun, M. J. H., Gelderman, C. J., & Pérez-Arendsen, J. (2015). Gedeeld leiderschap en proactiviteit in Het Nieuwe Werken. Gedrag & Organisatie, 28(4), 356–379. [Google Scholar]

- Coun, M. J. H., Peters, P., & Blomme, R. J. (2019). ‘Let’s share!’ The mediating role of employees’ self-determination in the relationship between transformational and shared leadership and perceived knowledge sharing among peers. European Management Journal, 37(4), 481–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coun, M. J. H., Peters, P., Blomme, R. J., & Schaveling, J. (2022). ‘To empower or not to empower, that’s the question’: Using an empowerment process approach to explain employees’ workplace proactivity. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 33(14), 2829–2855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curcuruto, M., Strauss, K., Axtell, C., & Griffin, M. A. (2020). Voicing for safety in the workplace: A proactive goal-regulation perspective. Safety Science, 131, 104902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durrah, O. (2023). Do we need friendship in the workplace? The effect on innovative behavior and mediating role of psychological safety. Current Psychology, 42(32), 28597–28610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Baroudi, S., Khapova, S. N., Jansen, P. G., & Richardson, J. (2019). Individual and contextual predictors of team member proactivity: What do we know and where do we go from here? Human Resource Management Review, 29(4), 100671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkhwesky, Z. (2022). A systematic and major review of proactive environmental strategies in hospitality and tourism: Looking back for moving forward. Business Strategy and the Environment, 31(7), 3274–3301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteves, T., & Lopes, M. P. (2017). Crafting a calling: The mediating role of calling between challenging job demands and turnover intention. Journal of Career Development, 44(1), 34–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frazier, M. L., Fainshmidt, S., Klinger, R. L., Pezeshkan, A., & Vracheva, V. (2017). Psychological safety: A meta-analytic review and extension. Personnel Psychology, 70(1), 113–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallup. (2021). State of the global workplace: 2021 report. Available online: https://www.gallup.com/workplace/349484/state-of-the-global-workplace-2021.aspx (accessed on 12 April 2025).

- George, D., & Mallery, P. (2019). IBM SPSS statistics 26 step by step: A simple guide and reference. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Ghitulescu, B. E. (2013). Making change happen: The impact of work context on adaptive and proactive behaviors. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 49(2), 206–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gracia, F. J., Tomas, I., Martinez-Corcoles, M., & Peiro, J. M. (2020). Empowering leadership, mindful organizing and safety performance in a nuclear power plant: A multilevel structural equation model. Safety Science, 123, 104542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, M. A., Parker, S. K., & Mason, C. M. (2010). Leader vision and the development of adaptive and proactive performance: A longitudinal study. Journal of Applied Psychology, 95(1), 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Anderson, R., Tatham, R., & Black, W. (1998). Multivariate data analysis. Prentivce-Hall International. In. Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Harju, L. K., Kaltiainen, J., & Hakanen, J. J. (2021). The double-edged sword of job crafting: The effects of job crafting on changes in job demands and employee well-being. Human Resource Management, 60(6), 953–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S. E. (1989). Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. American Psychologist, 44(3), 513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G. (2001). Culture’s consequences: Comparing values, behaviors, institutions, and organizations across nations (2nd ed.). Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Hyrkkänen, U., Vanharanta, O., Kuusisto, H., Polvinen, K., & Vartiainen, M. (2023). Predictors of job crafting in SMEs working in an ICT-based mobile and multilocational manner. International Small Business Journal, 41(8), 873–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiemian News. (2017, July 27). What is Huawei’s iron triangle after all? Available online: https://www.jiemian.com/article/1576033.html (accessed on 12 April 2025).

- Jung, K. B., Kang, S.-W., & Choi, S. B. (2020). Empowering leadership, risk-taking behavior, and employees’ commitment to organizational change: The mediated moderating role of task complexity. Sustainability, 12(6), 2340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jutengren, G., Jaldestad, E., Dellve, L., & Eriksson, A. (2020). The potential importance of social capital and job crafting for work engagement and job satisfaction among health-care employees. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(12), 4272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S. R., Qammar, A., & Shafique, I. (2022). Participative climate, team job crafting and leaders’ job crafting: A moderated mediation model of team performance. International Journal of Organization Theory & Behavior, 25(3/4), 150–166. [Google Scholar]

- Khatoon, A., Rehman, S. U., Islam, T., & Ashraf, Y. (2024). Knowledge sharing through empowering leadership: The roles of psychological empowerment and learning goal orientation. Global Knowledge, Memory and Communication, 73(4/5), 682–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M., & Beehr, T. A. (2018). Can empowering leaders affect subordinates’ well-being and careers because they encourage subordinates’ job crafting behaviors? Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 25(2), 184–196. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, M., & Beehr, T. A. (2020). Job crafting mediates how empowering leadership and employees’ core self-evaluations predict favourable and unfavourable outcomes. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 29(1), 126–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M., & Beehr, T. A. (2021). The power of empowering leadership: Allowing and encouraging followers to take charge of their own jobs. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 32(9), 1865–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M., & Beehr, T. A. (2023). Empowering leadership improves employees’ positive psychological states to result in more favorable behaviors. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 34(10), 2002–2038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. W., & Song, Y. (2020). Promoting employee job crafting at work: The roles of motivation and team context. Personnel Review, 49(3), 689–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M. C. C., Idris, M. A., & Delfabbro, P. H. (2017). The linkages between hierarchical culture and empowering leadership and their effects on employees’ work engagement: Work meaningfulness as a mediator. International Journal of Stress Management, 24(4), 392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenthaler, P. W., & Fischbach, A. (2019). A meta-analysis on promotion-and prevention-focused job crafting. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 28(1), 30–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M., Zhang, X., Ng, B. C. S., & Zhong, L. (2022). The dual influences of team cooperative and competitive orientations on the relationship between empowering leadership and team innovative behaviors. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 102, 103160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linders, D., Liao, C. Z.-P., & Wang, C.-M. (2018). Proactive e-Governance: Flipping the service delivery model from pull to push in Taiwan. Government Information Quarterly, 35(4), S68–S76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luu, T. T., Rowley, C., Dinh, C. K., Qian, D., & Le, H. Q. (2019). Team creativity in public healthcare organizations: The roles of charismatic leadership, team job crafting, and collective public service motivation. Public Performance & Management Review, 42(6), 1448–1480. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, S. L., Liao, H., & Campbell, E. M. (2013). Directive versus empowering leadership: A field experiment comparing impacts on task proficiency and proactivity. Academy of Management Journal, 56(5), 1372–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClelland, G. P., Leach, D. J., Clegg, C. W., & McGowan, I. (2014). Collaborative crafting in call centre teams. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 87(3), 464–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niessen, C., Weseler, D., & Kostova, P. (2016). When and why do individuals craft their jobs? The role of individual motivation and work characteristics for job crafting. Human Relations, 69(6), 1287–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palm, K., Bergman, A., & Rosengren, C. (2020). Towards more proactive sustainable human resource management practices? A study on stress due to the ICT-mediated integration of work and private life. Sustainability, 12(20), 8303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, S. K., & Collins, C. G. (2010). Taking stock: Integrating and differentiating multiple proactive behaviors. Journal of Management, 36(3), 633–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, P., Poutsma, E., Van der Heijden, B. I., Bakker, A. B., & Bruijn, T. d. (2014). Enjoying new ways to work: An HRM-process approach to study flow. Human Resource Management, 53(2), 271–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philip, J., & Kosmidou, V. (2023). How proactive personality and ICT-enabled technostress creators configure as drivers of job crafting. Journal of Management & Organization, 29(4), 724–744. [Google Scholar]

- Radstaak, M., & Hennes, A. (2017). Leader-member exchange fosters work engagement: The mediating role of job crafting. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 43(1), 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberge, V., & Boudrias, J.-S. (2021). The moderating role of employees’ psychological strain in the empowering leadership—Proactive performance relationship. International Journal of Stress Management, 28(3), 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sameer, Y. M. (2018). Innovative behavior and psychological capital: Does positivity make any difference? Journal of Economics and Management, 32(2), 75–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, D. N. K., & Kumar, N. (2022). Post-pandemic human resource management: Challenges and opportunities. SSRN. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, P. N., & Kirkman, B. L. (2015). Leveraging leaders: A literature review and future lines of inquiry for empowering leadership research. Group & Organization Management, 40(2), 193–237. [Google Scholar]

- Su, X.-Y., Wang, L.-Y., & Zhang, L. (2022). Workplace relationships and employees’ proactive behavior: Organization-based self-esteem as a mediator. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 50(5), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y., Liang, J., Hare, R., & Wang, F.-Y. (2020). A personalized learning system for parallel intelligent education. IEEE Transactions on Computational Social Systems, 7(2), 352–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarafdar, M., & Saunders, C. S. (2022). Remote, mobile, and blue-collar: ICT-enabled job crafting to elevate occupational well-being. Journal of the Association for Information Systems, 23(3), 707–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tims, M., Bakker, A. B., & Derks, D. (2012). Development and validation of the job crafting scale. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 80(1), 173–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uen, J.-F., Vandavasi, R. K. K., Lee, K., Yepuru, P., & Saini, V. (2021). Job crafting and psychological capital: A multi-level study of their effects on innovative work behaviour. Team Performance Management: An International Journal, 27(1/2), 145–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, N. H., Nguyen, T. T., & Nguyen, H. T. H. (2021). Linking intrinsic motivation to employee creativity: The role of empowering leadership. The Journal of Asian Finance, Economics and Business, 8(3), 595–604. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.-J., & Yang, I.-H. (2021). Why and how does empowering leadership promote proactive work behavior? An examination with a serial mediation model among hotel employees. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(5), 2386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H., Demerouti, E., & Bakker, A. B. (2016). A review of job-crafting research: The role of leader behaviors in cultivating successful job crafters. In Proactivity at work (pp. 95–122). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W., Kang, S.-W., & Choi, S. B. (2022). Servant leadership and creativity: A study of the sequential mediating roles of psychological safety and employee well-being. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 807070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, B., & Li, J. (2022). Understanding the impact of environmentally specific servant leadership on employees’ pro-environmental behaviors in the workplace: Based on the proactive motivation model. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(1), 567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zehir, C., & Celebi, S. (2022). The mediating role of explicit knowledge sharing in the relationship between empowering leadership and proactive work behavior in defense industry enterprises. International Journal of Research in Business and Social Science (2147–4478), 11(5), 225–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z., Zyphur, M. J., & Preacher, K. J. (2009). Testing multilevel mediation using hierarchical linear models: Problems and solutions. Organizational Research Methods, 12(4), 695–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Team Leaders | Employees Demographic | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Percent (Number) | Characteristic | Percent (Number) |

| Gender | Gender | ||

| Male | 54.1% (40) | Male | 51.4% (262) |

| Female | 45.9% (34) | Female | 48.6% (248) |

| Age | Age | ||

| 20–30 | 4.1% (3) | 20–30 | 39.0% (199) |

| 31–40 | 36.4% (27) | 31–40 | 44.9% (229) |

| 41–50 | 44.6% (33) | 41–50 | 12.7% (65) |

| >50 | 14.9% (11) | >50 | 3.4% (17) |

| Education level | Education level | ||

| Junior College degree or below | 24.3% (18) | Junior College degree or below | 37.1% (189) |

| Bachelor’s degree | 68.9% (51) | Bachelor’s degree | 58.8% (300) |

| Master’s degree or above | 6.8% (5) | Master’s degree or above | 4.1% (21) |

| ICT-usage frequency | ICT-usage frequency | ||

| Below 70%/per day | 4.1% (3) | Below 70%/per day | 33.9% (173) |

| 70–85%/per day | 51.3% (38) | 70–85%/per day | 49.0% (250) |

| Above 85%/per day | 44.6% (33) | Above 85%/per day | 17.1% (87) |

| Team size | |||

| 2–5 people | 18.9% (14) | ||

| 6–9 people | 78.4% (58) | ||

| More than 10 people | 2.7% (2) | ||

| Variable | Items | Alpha | Factor Loading | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Empowering leadership | 12 | 0.773 | 0.687–0.818 | 0.775 | 0.534 |

| Team job crafting | 5 | 0.942 | 0.850–0.944 | 0.943 | 0.769 |

| Psychological safety | 5 | 0.832 | 0.634–0.748 | 0.833 | 0.501 |

| Access to knowledge via ICT | 4 | 0.909 | 0.830–0.840 | 0.909 | 0.714 |

| Workplace proactivity | 13 | 0.896 | 0.809–0.870 | 0.896 | 0.685 |

| Variable | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Empowering leadership | 3.847 | 0.556 | (0.731) | ||||

| Team job crafting | 3.298 | 1.217 | 0.567 ** | (0.877) | |||

| Psychological safety | 3.930 | 0.780 | 0.317 ** | 0.236 ** | (0.708) | ||

| Access to knowledge via ICT | 3.498 | 1.124 | 0.201 * | 0.102 * | 0.115 ** | (0.845) | |

| Workplace proactivity | 3.298 | 0.821 | 0.550 ** | 0.450 ** | 0.387 ** | 0.021 | (0.828) |

| Null Model 1 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Null Model 2 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | Model 7 | Model 8 | Model 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Workplace Proactivity | Psychological Safety | Workplace Proactivity | ||||||||

| Intercept | 3.311 *** | 3.314 *** | 3.311 *** | 3.310 *** | 3.927 *** | 3.926 *** | 3.314 *** | 3.312 *** | 3.313 *** | 3.310 *** | 3.313 *** |

| Level 1 | |||||||||||

| Employee gender | 0.028 | 0.030 | 0.035 | 0.065 | 0.012 | 0.016 | 0.029 | 0.039 | 0.035 | ||

| Employee age | 0.020 | 0.027 | 0.020 | 0.042 | 0.010 | 0.019 | 0.020 | 0.009 | 0.015 | ||

| Employee education | −0.038 | −0.058 | −0.058 | −0.050 | −0.029 | −0.047 | −0.037 | −0.047 | −0.041 | ||

| ICT use in daily work | 0.022 | 0.021 | 0.025 | −0.013 | 0.023 | 0.024 | 0.022 | 0.029 | 0.017 | ||

| Psychological safety | 0.233 *** | 0.189 *** | |||||||||

| Level 2 | |||||||||||

| Leader gender | −0.098 | −0.111 | −0.105 | −0.098 | −0.078 | −0.091 | −0.097 | −0.111 | −0.102 | ||

| Leader age | −0.135 | −0.017 | −0.006 | 0.008 | −0.123 | −0.018 | −0.134 | −0.016 | −0.017 | ||

| Leader education | 0.183 | 0.124 | 0.135 | 0.316 *** | 0.102 | 0.065 | 0.183 | 0.162 | 0.158 | ||

| ICT use in daily work | 0.249 | 0.027 | 0.004 | 0.073 | 0.203 | 0.013 | 0.249 | 0.025 | 0.037 | ||

| Team size | −0.238 | −0.086 | −0.054 | 0.026 | −0.224 | −0.091 | −0.238 | −0.050 | −0.018 | ||

| Empowering leadership | 1.318 *** | 0.887 *** | 0.734 *** | 1.181 *** | |||||||

| Team job crafting | 0.263 *** | 0.628 *** | 0.575 *** | ||||||||

| Access to knowledge via ICT | 0.003 | −0.025 | −0.011 | ||||||||

| TJB* ICT | 0.150 ** | ||||||||||

| R (Sigma_squared) | 0.388 | 0.390 | 0.394 | 0.395 | 0.416 | 0.419 | 0.381 | 0.382 | 0.390 | 0.393 | 0.390 |

| U(Tau) | 0.277 | 0.260 | 0.036 | 0.024 | 0.197 | 0.104 | 0.197 | 0.029 | 0.265 | 0.060 | 0.201 |

| Chi-square | 448.975 *** | 391.162 *** | 111.102 *** | 97.192 * | 309.495 *** | 178.785 *** | 320.158 *** | 103.207 ** | 397.158 *** | 135.720 *** | 307.822 *** |

| Deviance | 1095.229 | 1115.771 | 1037.165 | 1033.536 | 1106.837 | 1101.563 | 1091.242 | 1022.503 | 1117.279 | 1057.675 | 1102.199 |

| Variable | A | Sa | b | Sb | a*b | Z | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EL-TJB-WP | 0.834 | 0.151 | 0.592 | 0.061 | 0.439 | 7.825 | 0.000 |

| EL-PS-WP | 0.514 | 0.153 | 0.275 | 0.088 | 0.141 | 4.134 | 0.000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Piao, J.; Hahn, J. How Empowering Leadership Drives Proactivity in the Chinese IT Industry: Mediation Through Team Job Crafting and Psychological Safety with ICT Knowledge as a Moderator. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 609. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15050609

Piao J, Hahn J. How Empowering Leadership Drives Proactivity in the Chinese IT Industry: Mediation Through Team Job Crafting and Psychological Safety with ICT Knowledge as a Moderator. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(5):609. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15050609

Chicago/Turabian StylePiao, Juanxiu, and Juhee Hahn. 2025. "How Empowering Leadership Drives Proactivity in the Chinese IT Industry: Mediation Through Team Job Crafting and Psychological Safety with ICT Knowledge as a Moderator" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 5: 609. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15050609

APA StylePiao, J., & Hahn, J. (2025). How Empowering Leadership Drives Proactivity in the Chinese IT Industry: Mediation Through Team Job Crafting and Psychological Safety with ICT Knowledge as a Moderator. Behavioral Sciences, 15(5), 609. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15050609