When Cultural Resources Amplify Psychological Strain: Off-Work Music Listening, Homophily, and the Homesickness–Burnout Link Among Migrant Workers

Abstract

1. Introduction

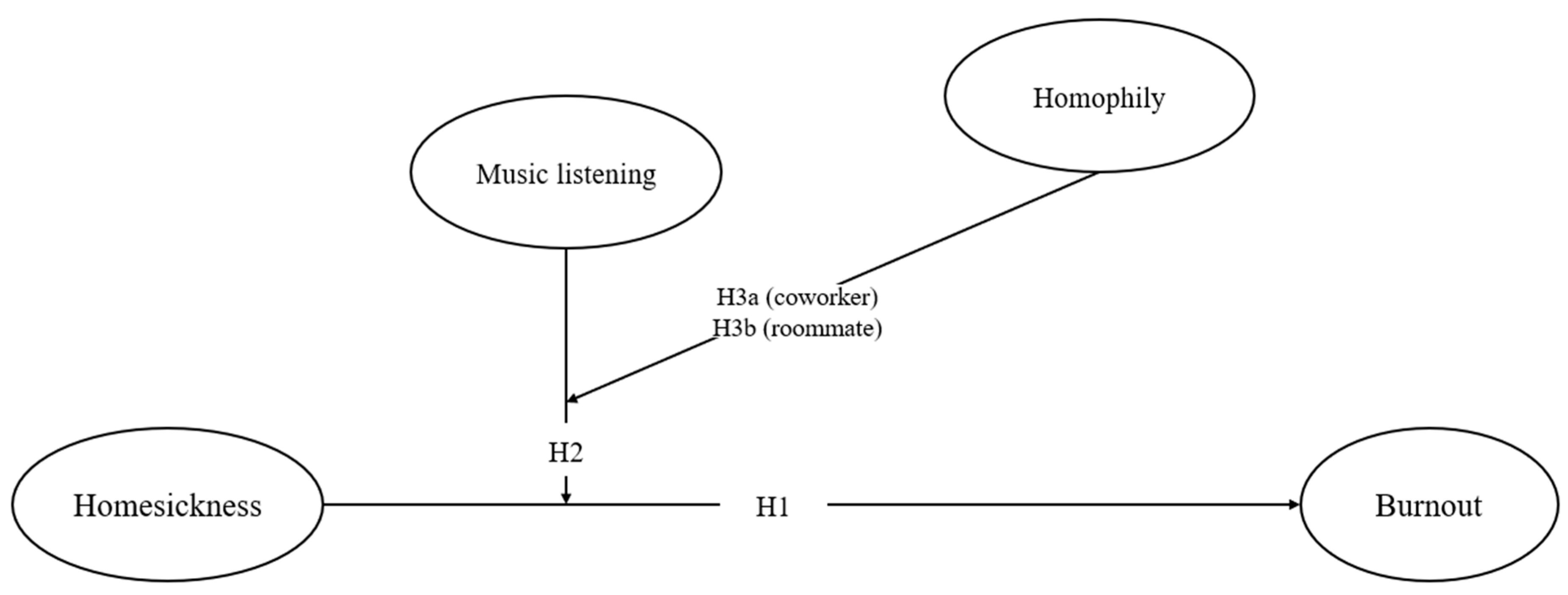

2. Theoretical Background and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Homesickness and Burnout

2.2. Music Listening as a Resource-Replenishing or Demand-Amplifying Activity

2.3. Music Listening with Homophilic Coworkers and Roommates

3. Methods

3.1. Sampling

3.2. Measures

3.3. Reliability and Validity

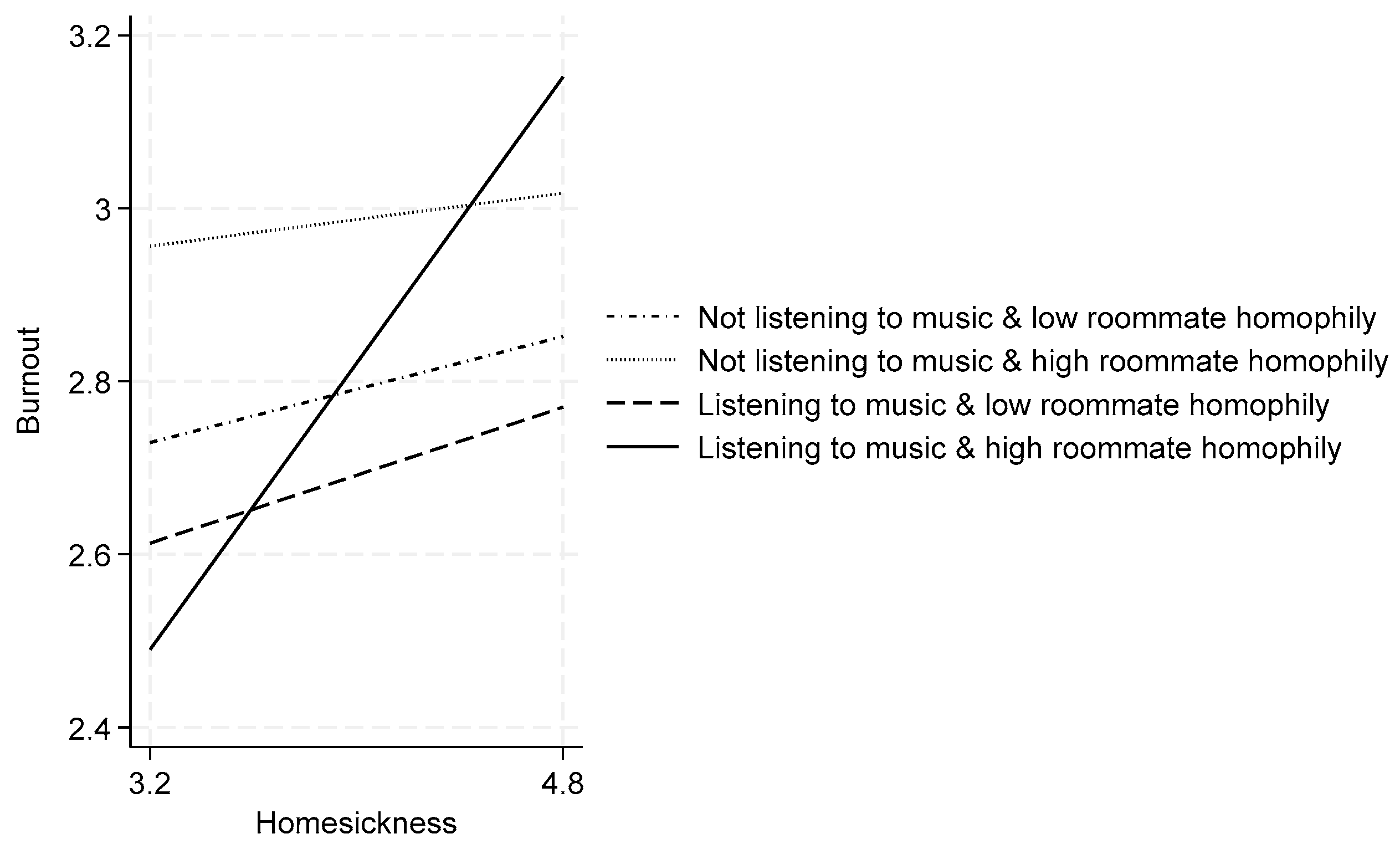

4. Results

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | These cities are Shenzhen, Dongguan, Foshan, Zhongshan, and Huizhou. Guangzhou was excluded, as the local government was unable to assist us with access. |

References

- Albert, S. (1977). Temporal comparison theory. Psychological Review, 84(6), 485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bader, B. (2015). The power of support in high-risk countries: Compensation and social support as antecedents of expatriate work attitudes. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 26(13), 1712–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bader, B., Stoermer, S., Bader, A. K., & Schuster, T. (2018). Institutional discrimination of women and workplace harassment of female expatriates: Evidence from 25 host countries. Journal of Global Mobility, 6(1), 40–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2017). Job demands–resources theory: Taking stock and looking forward. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 22(3), 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., & Sanz-Vergel, A. (2023). Job demands–resources theory: Ten years later. Annual Review of Organisational Psychology and Organisational Behavior, 10(1), 25–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, F. S., Grimm, K. J., Robins, R. W., Wildschut, T., Sedikides, C., & Janata, P. (2010). Music-evoked nostalgia: Affect, memory, and personality. Emotion, 10(3), 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, J. W. (1997). Immigration, acculturation, and adaptation. Applied Psychology, 46(1), 5–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, S., & Ram, A. (2009). Theorizing identity in transnational and diaspora cultures: A critical approach to acculturation. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 33(2), 140–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, R., Schonfeld, I. S., & Laurent, E. (2018). A neglected problem in burnout research. Academic Medicine, 93(4), 518–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boer, D., & Abubakar, A. (2014). Music listening in families and peer groups: Benefits for young people’s social cohesion and emotional wellbeing across four cultures. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boer, D., & Fischer, R. (2012). Towards a holistic model of functions of music listening across cultures: A culturally decentred qualitative approach. Psychology of Music, 40(2), 179–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonde, L. O., & Theorell, T. (2018). Music and public health. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Boym, S. (2001). The Future of Nostalgia. Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, K. W. (2021). Internal migration in China: Integrating migration with urbanization policies and hukou reform. KNOMAD—Policy Note, 16, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Charlesworth, B. (2021). The effect of homesickness on the psychological wellbeing of medical and non-medical students. UCC Student Medical Journal, 2, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cousin, B., & Chauvin, S. (2017). Old money, networks and distinction: The social and service clubs of Milan’s upper classes. In Cities and the super-rich: Real estate, elite practices and urban political economies (pp. 147–165). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Crawford, E. R., LePine, J. A., & Rich, B. L. (2010). Linking job demands and resources to employee engagement and burnout: A theoretical extension and meta-analytic test. Journal of Applied Psychology, 95(5), 834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Martini Ugolotti, N. (2022). Music-making and forced migrants’ affective practices of diasporic belonging. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 48(1), 92–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., Nachreiner, F., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2001). The job demands-resources model of burnout. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(3), 499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, D., Derks, D., Bakker, A. B., & Lu, C. q. (2018). Does homesickness undermine the potential of job resources? A perspective from the work–home resources model. Journal of Organisational Behavior, 39(1), 96–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, C. C., & Chen, C. (2020). Left behind? Migration stories of two women in rural China. Social Inclusion, 8(2), 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, S. (2016). Homesickness, cognition and health. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, S., Elder, L., & Peacock, G. (1990). Homesickness in a school in the Australian Bush. Children’s Environments Quarterly, 7(3), 15–22. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes-Sánchez, N., Espino-Payá, A., Prantner, S., Sabatinelli, D., Pastor, M. C., & Junghöfer, M. (2025). On joy and sorrow: Neuroimaging meta-analyses of music-induced emotion. Imaging Neuroscience, 3, imag_a_00425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu Keung Wong, D., & Song, H. X. (2008). The resilience of migrant workers in Shanghai China: The roles of migration stress and meaning of migration. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 54(2), 131–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gabrielsson, A. (2011). Strong experiences with music: Music is much more than just music. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Garrido, S., & Davidson, J. W. (2019). Music, nostalgia and memory. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Garrido, S., & Schubert, E. (2015). Moody melodies: Do they cheer us up? A study of the effect of sad music on mood. Psychology of Music, 43(2), 244–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, W.-J., Zhu, S.-J., Zhu, X.-Y., & Chu, A.-Q. (2025). Gender differences in co-rumination and transition shock among nursing interns in China: A cross-sectional study. BMC Nursing, 24(1), 420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haake, A. B. (2011). Individual music listening in workplace settings: An exploratory survey of offices in the UK. Musicae Scientiae, 15(1), 107–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hack-Polay, D. (2012). When home isn’t home: A study of homesickness and coping strategies among migrant workers and expatriates. International Journal of Psychological Studies, 4(3), 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haggard, D. L., Robert, C., & Rose, A. J. (2011). Co-rumination in the workplace: Adjustment trade-offs for men and women who engage in excessive discussions of workplace problems. Journal of Business and Psychology, 26, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C. M., & Gudergan, S. (2017). Advanced issues in partial least squares structural equation modeling. SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Hartup, W. W., & Stevens, N. (1997). Friendships and adaptation in the life course. Psychological Bulletin, 121(3), 355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatfield, E., Cacioppo, J. T., & Rapson, R. L. (1993). Emotional contagion. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 2(3), 96–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendrickson, B., Rosen, D., & Aune, R. K. (2011). An analysis of friendship networks, social connectedness, homesickness, and satisfaction levels of international students. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 35(3), 281–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S. E. (2002). Social and psychological resources and adaptation. Review of General Psychology, 6(4), 307–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, K., Xiao, H., & Yang, X. (2013). Why immigrants travel to their home places: Social capital and acculturation perspective. Tourism Management, 36, 304–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Labour Organization. (2022). ILO global estimates on international migrant workers: Executive summary. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/sites/default/files/2024-12/MIGRANT%20%E2%80%93%20ILO%20Global%20Estimates%20on%20International%20Migrant%20Workers_ES_E_WEB_0.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2024).

- Jakubowski, K., Belfi, A. M., & Eerola, T. (2021). Phenomenological differences in music-and television-evoked autobiographical memories. Music Perception: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 38(5), 435–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janata, P., Tomic, S. T., & Rakowski, S. K. (2007). Characterisation of music-evoked autobiographical memories. Memory, 15(8), 845–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Y., & Zheng, M. (2024). The inductive effect of musical mode types on emotions and physiological responses: Chinese pentatonic scales versus Western major/minor modes. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, 1414014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joudrey, A. D., & Wallace, J. E. (2009). Leisure as a coping resource: A test of the job demand-control-support model. Human Relations, 62(2), 195–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juslin, P. N., & Västfjäll, D. (2008). Emotional responses to music: The need to consider underlying mechanisms. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 31(5), 559–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, A., Rohlfing, R., Janss, A., & Stafford, R. (2025). A call to rethink music interventions implementation to address health disparities. Arts & Health, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, D., Le Galès, P., & Vitale, T. (2017). Assimilation, security, and borders in the member States. In Reconfiguring European States in Crisis (pp. 428–450). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kleinbaum, A. M., Stuart, T. E., & Tushman, M. L. (2013). Discretion within constraint: Homophily and structure in a formal organisation. Organisation Science, 24(5), 1316–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R. B. (2023). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Guilford publications. [Google Scholar]

- Kovács, L. N., Kocsel, N., Tóth, Z., Smahajcsik-Szabó, T., Karsai, S., & Kökönyei, G. (2025). The daily relations of co-rumination and perseverative cognition. Scientific Reports, 15(1), 3021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kruse, H. (2010). Local identity and independent music scenes, online and off. Popular Music and Society, 33(5), 625–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.-Y. (2012). At the crossroads of migrant workers, class, and media: A case study of a migrant workers’ television project. Media, Culture & Society, 34(3), 312–327. [Google Scholar]

- Lesiuk, T. (2005). The effect of music listening on work performance. Psychology of Music, 33(2), 173–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J., Chang, S.-S., Yip, P. S., Li, J., Jordan, L. P., Tang, Y., Hao, Y., Huang, X., Yang, N., & Chen, C. (2014). Mental wellbeing amongst younger and older migrant workers in comparison to their urban counterparts in Guangzhou city, China: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health, 14, 1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J., & Rose, N. (2017). Urban social exclusion and mental health of China’s rural-urban migrants—A review and call for research. Health & Place, 48, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X., Stanton, B., Fang, X., & Lin, D. (2006). Social stigma and mental health among rural-to-urban migrants in China: A conceptual framework and future research needs. World Health & Population, 8(3), 14. [Google Scholar]

- Linnemann, A., Ditzen, B., Strahler, J., Doerr, J. M., & Nater, U. M. (2015). Music listening as a means of stress reduction in daily life. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 60, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H., Li, S., Xiao, Q., & Feldman, M. (2014). Social support and psychological wellbeing under social change in urban and rural China. Social Indicators Research, 119, 979–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., Li, Z., & Breitung, W. (2012). The social networks of new-generation migrants in China’s urbanized villages: A case study of Guangzhou. Habitat International, 36(1), 192–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundqvist, L.-O., Carlsson, F., Hilmersson, P., & Juslin, P. N. (2009). Emotional responses to music: Experience, expression, and physiology. Psychology of Music, 37(1), 61–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H., Yang, H., Xu, X., Yun, L., Chen, R., Chen, Y., Xu, L., Liu, J., Liu, L., & Liang, H. (2016). Relationship between occupational stress and job burnout among rural-to-urban migrant workers in Dongguan, China: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open, 6(8), e012597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, H., Topolansky Barbe, F., & Zhang, Y. C. (2018). Can social capital and psychological capital improve the entrepreneurial performance of the new generation of migrant workers in China? Sustainability, 10(11), 3964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mak, J., Roberts, B., & Zimmerman, C. (2021). Coping with migration-related stressors: A systematic review of the literature. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 23, 389–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, H., Amijos, M. T., & Few, R. (2020). “Telling it in our own way”: Doing music-enhanced interviews with people displaced by violence in Colombia. New Area Studies, 1(1), 132–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazurkiewicz, R., Korenstein, D., Fallar, R., & Ripp, J. (2012). The prevalence and correlations of medical student burnout in the pre-clinical years: A cross-sectional study. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 17(2), 188–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMillan, C. (2019). Tied together: Adolescent friendship networks, immigrant status, and health outcomes. Demography, 56(3), 1075–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McPherson, M., Smith-Lovin, L., & Cook, J. M. (2001). Birds of a feather: Homophily in social networks. Annual Review of Sociology, 27(1), 415–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morelli, N., & Vitale, T. (2020). Take politics off the table: A study of Italian youth’s self-managed dairy restriction and healthy consumerism. Social Science Information, 59, 679–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Bureau of Statistics of China. (2022, January 17). National economy was generally stable with steady progress in 2021. Available online: http://www.stats.gov.cn/english/PressRelease/202201/t20220117_1826409.html (accessed on 17 January 2024).

- National Bureau of Statistics of China. (2024, January 17). National economy witnessed momentum of recovery with solid progress in high-quality development in 2023. Available online: https://www.stats.gov.cn/english/PressRelease/202401/t20240117_1946605.html (accessed on 17 January 2024).

- Nguyen, A.-M. D., & Benet-Martínez, V. (2013). Biculturalism and adjustment: A meta-analysis. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 44(1), 122–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nils, F., & Rimé, B. (2012). Beyond the myth of venting: Social sharing modes determine the benefits of emotional disclosure. European Journal of Social Psychology, 42(6), 672–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oelberger, C. R. (2019). The dark side of deeply meaningful work: Work-relationship turmoil and the moderating role of occupational value homophily. Journal of Management Studies, 56(3), 558–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, A., Waldstrøm, C., & Shah, N. P. (2023). The coevolution of emotional job demands and work-based social ties and their effect on performance. Journal of Management, 49(5), 1601–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, N. H., Tran, M. D., Le, A. D., & Le, T. L. (2021). Determinants influencing the decision of internal migration in the context of an emerging country. Corporate Governance and Organisational Behavior Review, 5(2), 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pistrick, E. (2017). Performing nostalgia: Migration culture and creativity in south Albania. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Poyrazli, S., & Lopez, M. D. (2007). An exploratory study of perceived discrimination and homesickness: A comparison of international students and American students. The Journal of Psychology, 141(3), 263–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qassim, A. A., & Abedelrahim, S. S. (2024). Healthcare Resilience in Saudi Arabia: The Interplay of Occupational Safety, Staff Engagement, and Resilience. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 21(11), 1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramnarine, T. K. (2013). Musical performance in the diaspora: Introduction. In Musical performance in the diaspora (pp. 1–17). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Rattrie, L. T., Kittler, M. G., & Paul, K. I. (2020). Culture, burnout, and engagement: A meta-analysis on national cultural values as moderators in JD-R theory. Applied Psychology, 69(1), 176–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reißmann, S., Flothow, A., Harth, V., & Mache, S. (2022). Exploring job demands and resources in psychotherapists treating displaced people—A scoping review. Psychotherapy Research, 32(8), 1076–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimé, B. (2009). Emotion elicits the social sharing of emotion: Theory and empirical review. Emotion Review, 1(1), 60–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, A. J. (2002). Co–rumination in the friendships of girls and boys. Child Development, 73(6), 1830–1843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, M., & Wilson, A. E. (2003). Autobiographical memory and conceptions of self: Getting better all the time. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 12(2), 66–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saarikallio, S. (2012). Development and validation of the brief music in mood regulation scale (B-MMR). Music Perception: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 30(1), 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulkind, M. D., Hennis, L. K., & Rubin, D. C. (1999). Music, emotion, and autobiographical memory: They’re playing your song. Memory & Cognition, 27, 948–955. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, B. A., Awasty, N., Li, S., Conlon, D. E., Johnson, R. E., Voorhees, C. M., & Passantino, L. G. (2024). Too much of a good thing? A multilevel examination of listening to music at work. Journal of Applied Psychology, 110(5), 741–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, X., & Franklin, P. (2014). Business expatriates’ cross-cultural adaptation and their job performance. Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources, 52(2), 193–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R. A., & Khawaja, N. G. (2011). A review of the acculturation experiences of international students. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 35(6), 699–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonnentag, S., Mojza, E. J., Demerouti, E., & Bakker, A. B. (2012). Reciprocal relations between recovery and work engagement: The moderating role of job stressors. Journal of Applied Psychology, 97(4), 842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stroebe, M., Schut, H., & Nauta, M. (2015). Homesickness: A systematic review of the scientific literature. Review of General Psychology, 19(2), 157–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stroebe, M., Schut, H., & Nauta, M. H. (2016). Is homesickness a mini-grief? Development of a dual process model. Clinical Psychological Science, 4(2), 344–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stroebe, M., Van Vliet, T., Hewstone, M., & Willis, H. (2002). Homesickness among students in two cultures: Antecedents and consequences. The British Journal of Psychology, 93(2), 147–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweller, J. (1994). Cognitive load theory, learning difficulty, and instructional design. Learning and Instruction, 4(4), 295–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabarani, P., Restubog, S. L. D., Kiazad, K., Lagios, C., Schilpzand, P., & Wang, L. (2025). Heartsick for home: An integrative review of employee homesickness and an agenda for future research. Group & Organisation Management. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S., Feng, J., & Li, M. (2017). Housing tenure choices of rural migrants in urban destinations: A case study of Jiangsu Province, China. Housing Studies, 32(3), 361–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S., Zhou, J., Druta, O., & Li, X. (2023). Settlement in Nanjing among Chinese rural migrant families: The role of changing and persistent family norms. Urban Studies, 60(6), 1083–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terry, M. L., Leary, M. R., & Mehta, S. (2013). Self-compassion as a buffer against homesickness, depression, and dissatisfaction in the transition to college. Self and Identity, 12(3), 278–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, X. (2018). Gendered labour regimes: On the organizing of domestic workers in urban China. Asian Journal of German and European Studies, 3(1), 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vacca, R., Cañarte, D., & Vitale, T. (2022). Beyond ethnic solidarity: The diversity and specialisation of social ties in a stigmatised migrant minority. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 48(13), 3113–3141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Oudenhoven, J. P., & Ward, C. (2013). Fading majority cultures: The implications of transnationalism and demographic changes for immigrant acculturation. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 23(2), 81–97. [Google Scholar]

- Van Oudenhoven, J. P., Ward, C., & Masgoret, A.-M. (2006). Patterns of relations between immigrants and host societies. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 30(6), 637–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B., & Collins, F. L. (2016). Becoming cosmopolitan? Hybridity and intercultural encounters amongst 1.5 generation Chinese migrants in New Zealand. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 39(15), 2777–2795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B., Li, X., Stanton, B., & Fang, X. (2010). The influence of social stigma and discriminatory experience on psychological distress and quality of life among rural-to-urban migrants in China. Social Science & Medicine, 71(1), 84–92. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z., Lin, L., Tang, S., & Xiao, Y. (2023). Migration and migrants in Chinese cities: New trends, challenges and opportunities to theorise with urban China. Transactions in Planning and Urban Research, 2(4), 317–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y., & Hanley, J. (2015). Rural-to-urban migration, family resilience, and policy framework for social support in China. Asian Social Work and Policy Review, 9(1), 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wildschut, T., Sedikides, C., Arndt, J., & Routledge, C. (2006). Nostalgia: Content, triggers, functions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 91(5), 975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, A. E., & Ross, M. (2000). The frequency of temporal-self and social comparisons in people’s personal appraisals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 78(5), 928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, A. E., & Shanahan, E. (2020). Temporal comparisons in a social world. In Social comparison, judgment, and behavior (pp. 309–344). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y., Xu, M., Li, S., Wang, H., & Dong, Q. (2024). The land of homesickness: The impact of homesteads on the social integration of rural migrants. PLoS ONE, 19(7), e0307605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, C., Yuan, X., & Zhang, J. (2022). City size, family migration, and gender wage gap: Evidence from rural–urban migrants in China. Regional Science and Urban Economics, 97, 103834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B., & Qu, D. Z. (2020). Rural to urban migrant workers in China: Challenges of risks and rights. Asian Education and Development Studies, 10(1), 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X. (2025, February 25). SCIO briefing on China’s economic performance in 2024. The State Council Information Office of the People’s Republic of China. Available online: http://english.scio.gov.cn/m/pressroom/2025-02/25/content_117731965_9.html (accessed on 25 February 2025).

- Ye, J. (2006). An examination of acculturative stress, interpersonal social support, and use of online ethnic social groups among Chinese international students. The Howard Journal of Communications, 17(1), 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, Z., Li, S., Jin, X., & Feldman, M. W. (2013). The role of social networks in the integration of Chinese rural–urban migrants: A migrant–resident tie perspective. Urban Studies, 50(9), 1704–1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X., Jiang, X., Ni, P., Li, H., Li, C., Zhou, Q., Ou, Z., Guo, Y., & Cao, J. (2021). Association between resilience and burnout of front-line nurses at the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic: Positive and negative affect as mediators in Wuhan. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 30(4), 939–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., Li, Y., Zhuang, X., Liu, H., Xu, Y., Zhang, S., Yan, Y., & Li, Y. (2024). Can digital financial inclusion help reduce migrant workers’ overwork? Evidence from China. Frontiers in Public Health, 12, 1357481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., Wang, C., Pan, W., Zheng, J., Gao, J., Huang, X., Cai, S., Zhai, Y., Latour, J. M., & Zhu, C. (2020). Stress, burnout, and coping strategies of frontline nurses during the COVID-19 epidemic in Wuhan and Shanghai, China. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 565520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., You, C., Pundir, P., & Meijering, L. (2023). Migrants’ community participation and social integration in urban areas: A scoping review. Cities, 141, 104447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, B.-L., Liu, T.-B., Huang, J.-X., Fung, H. H., Chan, S. S., Conwell, Y., & Chiu, H. F. (2016). Acculturative stress of Chinese rural-to-urban migrant workers: A qualitative study. PLoS ONE, 11(6), e0157530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X., Sedikides, C., Wildschut, T., & Gao, D.-G. (2008). Counteracting loneliness: On the restorative function of nostalgia. Psychological Science, 19(10), 1023–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Mean | Std. Deviation | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 0.452 | 0.498 | 1 | ||||||||||

| Age | 25.309 | 6.562 | 0.145 | 1 | |||||||||

| Married | 0.377 | 0.485 | 0.018 | 0.571 | 1 | ||||||||

| Education | 2.751 | 0.763 | 0.080 | −0.041 | −0.137 | 1 | |||||||

| Tenure | 2.244 | 3.375 | 0.085 | 0.432 | 0.354 | −0.051 | 1 | ||||||

| Cross-province | 0.769 | 0.421 | 0.008 | −0.006 | 0.024 | −0.053 | −0.022 | 1 | |||||

| Burnout | 2.871 | 1.128 | −0.021 | −0.103 | −0.055 | −0.035 | −0.060 | 0.033 | 1 | ||||

| Homesickness | 4.007 | 0.817 | −0.109 | −0.015 | 0.036 | −0.131 | −0.012 | 0.066 | 0.074 | 1 | |||

| Off-work music listening | 0.184 | 0.387 | −0.039 | −0.064 | −0.070 | 0.044 | −0.046 | 0.003 | −0.049 | −0.010 | 1 | ||

| Coworker homophily | 3.233 | 0.852 | −0.015 | 0.091 | 0.089 | 0.007 | 0.054 | 0.002 | 0.063 | 0.096 | −0.003 | 1 | |

| Roommate homophily | 3.206 | 0.754 | 0.021 | 0.111 | 0.105 | −0.004 | 0.087 | −0.013 | 0.075 | 0.106 | −0.040 | 0.697 | 1 |

| Measurement Items | Factor Loading | Cronbach’s α | Composite Reliability | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Burnout (BU) | 0.817 | 0.894 | 0.738 | |

| BU1 | 0.811 | |||

| BU2 | 0.903 | |||

| BU3 | 0.860 | |||

| Homesickness (HS) | 0.741 | 0.839 | 0.566 | |

| HS1 | 0.753 | |||

| HS2 | 0.728 | |||

| HS3 | 0.794 | |||

| HS4 | 0.732 | |||

| Coworker homophily (CH) | 0.740 | 0.836 | 0.508 | |

| CH1 | 0.629 | |||

| CH2 | 0.749 | |||

| CH3 | 0.799 | |||

| CH4 | 0.783 | |||

| CH5 | 0.577 | |||

| Roommate homophily (RH) | 0.803 | 0.867 | 0.568 | |

| RH1 | 0.697 | |||

| RH2 | 0.772 | |||

| RH3 | 0.810 | |||

| RH4 | 0.803 | |||

| RH5 | 0.676 |

| Variable | Homesickness | Burnout | Coworker Homophily | Roommate Homophily |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fornell-Larcker criteria | ||||

| Homesickness | 0.752 | |||

| Burnout | 0.074 | 0.859 | ||

| Coworker homophily | 0.096 | 0.063 | 0.713 | |

| Roommate homophily | 0.106 | 0.075 | 0.697 | 0.754 |

| Heterotrait-monotrait ratio (HTMT) | ||||

| Homesickness | ||||

| Burnout | 0.096 | |||

| Coworker homophily | 0.165 | 0.094 | ||

| Roommate homophily | 0.195 | 0.099 | 1.0196 | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Baseline | Music | Music | Roommates | Roommates | Coworkers | Coworkers |

| Male | 0.0594 | 0.0560 | 0.0549 | 0.0682 | 0.0682 | 0.0653 | 0.0690 |

| (0.0467) | (0.0467) | (0.0467) | (0.0499) | (0.0499) | (0.0474) | (0.0473) | |

| Age | −0.0168 *** | −0.0170 *** | −0.0168 *** | −0.0176 *** | −0.0176 *** | −0.0192 *** | −0.0190 *** |

| (0.00469) | (0.00469) | (0.00469) | (0.00501) | (0.00501) | (0.00476) | (0.00475) | |

| Married | −0.0364 | −0.0399 | −0.0408 | −0.0642 | −0.0608 | −0.0230 | −0.0187 |

| (0.0556) | (0.0556) | (0.0555) | (0.0601) | (0.0601) | (0.0562) | (0.0561) | |

| Education | −0.0608 * | −0.0584 * | −0.0552 * | −0.0572 | −0.0563 | −0.0633 * | −0.0636 * |

| (0.0326) | (0.0326) | (0.0325) | (0.0353) | (0.0353) | (0.0331) | (0.0330) | |

| Tenure | −0.00299 | −0.00314 | −0.00284 | −0.00634 | −0.00688 | −0.00606 | −0.00688 |

| (0.00775) | (0.00774) | (0.00773) | (0.00856) | (0.00856) | (0.00789) | (0.00788) | |

| Cross-province migrant | 0.100 * | 0.0980 * | 0.0937 * | 0.0796 | 0.0801 | 0.0914 * | 0.0905 * |

| (0.0530) | (0.0530) | (0.0529) | (0.0571) | (0.0571) | (0.0538) | (0.0537) | |

| Homesickness | 0.116 *** | 0.116 *** | 0.0750 ** | 0.0579 * | 0.126 | 0.0595 * | 0.205 |

| (0.0269) | (0.0268) | (0.0298) | (0.0324) | (0.122) | (0.0305) | (0.126) | |

| Off-work music listening | −0.107 ** | −0.950 *** | −0.941 *** | 1.709 | −0.898 *** | 3.159 *** | |

| (0.0538) | (0.271) | (0.289) | (1.061) | (0.275) | (1.188) | ||

| Homesickness × Off-work music listening | 0.210 *** | 0.204 *** | −0.431 * | 0.201 *** | −0.681 ** | ||

| (0.0662) | (0.0706) | (0.258) | (0.0672) | (0.289) | |||

| High-homophily roommates | 0.102 *** | 0.195 | |||||

| (0.0273) | (0.153) | ||||||

| Homesickness × High-homophily roommates | −0.0214 | ||||||

| (0.0369) | |||||||

| Music off work × High-homophily roommates | −0.824 *** | ||||||

| (0.318) | |||||||

| Homesickness × Off-work music listening× High-homophily roommates | 0.197 ** | ||||||

| (0.0768) | |||||||

| High-homophily coworkers | 0.143 *** | 0.361 ** | |||||

| (0.0296) | (0.160) | ||||||

| Homesickness × High-homophily coworkers | −0.0465 | ||||||

| (0.0385) | |||||||

| Music off work × High-homophily coworkers | −1.335 *** | ||||||

| (0.376) | |||||||

| Homesickness × Off-work music listening × High-homophily coworkers | 0.290 *** | ||||||

| (0.0903) | |||||||

| Constant | 2.913 *** | 2.916 *** | 2.809 *** | 2.659 *** | 2.368 *** | 2.519 *** | 1.845 *** |

| (0.484) | (0.483) | (0.290) | (0.320) | (0.570) | (0.315) | (0.591) | |

| Observations | 2725 | 2725 | 2725 | 2377 | 2377 | 2625 | 2625 |

| R-squared | 0.089 | 0.090 | 0.094 | 0.101 | 0.104 | 0.105 | 0.110 |

| Industry FE | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gu, C.; Ma, Z.; Li, X.; Zhang, J.; Huang, Q. When Cultural Resources Amplify Psychological Strain: Off-Work Music Listening, Homophily, and the Homesickness–Burnout Link Among Migrant Workers. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 666. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15050666

Gu C, Ma Z, Li X, Zhang J, Huang Q. When Cultural Resources Amplify Psychological Strain: Off-Work Music Listening, Homophily, and the Homesickness–Burnout Link Among Migrant Workers. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(5):666. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15050666

Chicago/Turabian StyleGu, Chenyuan, Zhuang Ma, Xiaoying Li, Jianjun Zhang, and Qihai Huang. 2025. "When Cultural Resources Amplify Psychological Strain: Off-Work Music Listening, Homophily, and the Homesickness–Burnout Link Among Migrant Workers" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 5: 666. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15050666

APA StyleGu, C., Ma, Z., Li, X., Zhang, J., & Huang, Q. (2025). When Cultural Resources Amplify Psychological Strain: Off-Work Music Listening, Homophily, and the Homesickness–Burnout Link Among Migrant Workers. Behavioral Sciences, 15(5), 666. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15050666