Advice-Taking for Objective Face Age Estimates Relative to Subjective Face Trustworthiness Estimates

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures and Procedure

2.2.1. Judge–Advisor Task

2.2.2. Confidence and Perceived Task Difficulty

2.2.3. Actual Task Difficulty

2.2.4. Cognitive Capacity

2.3. Judge–Advisor Task Data Cleaning

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

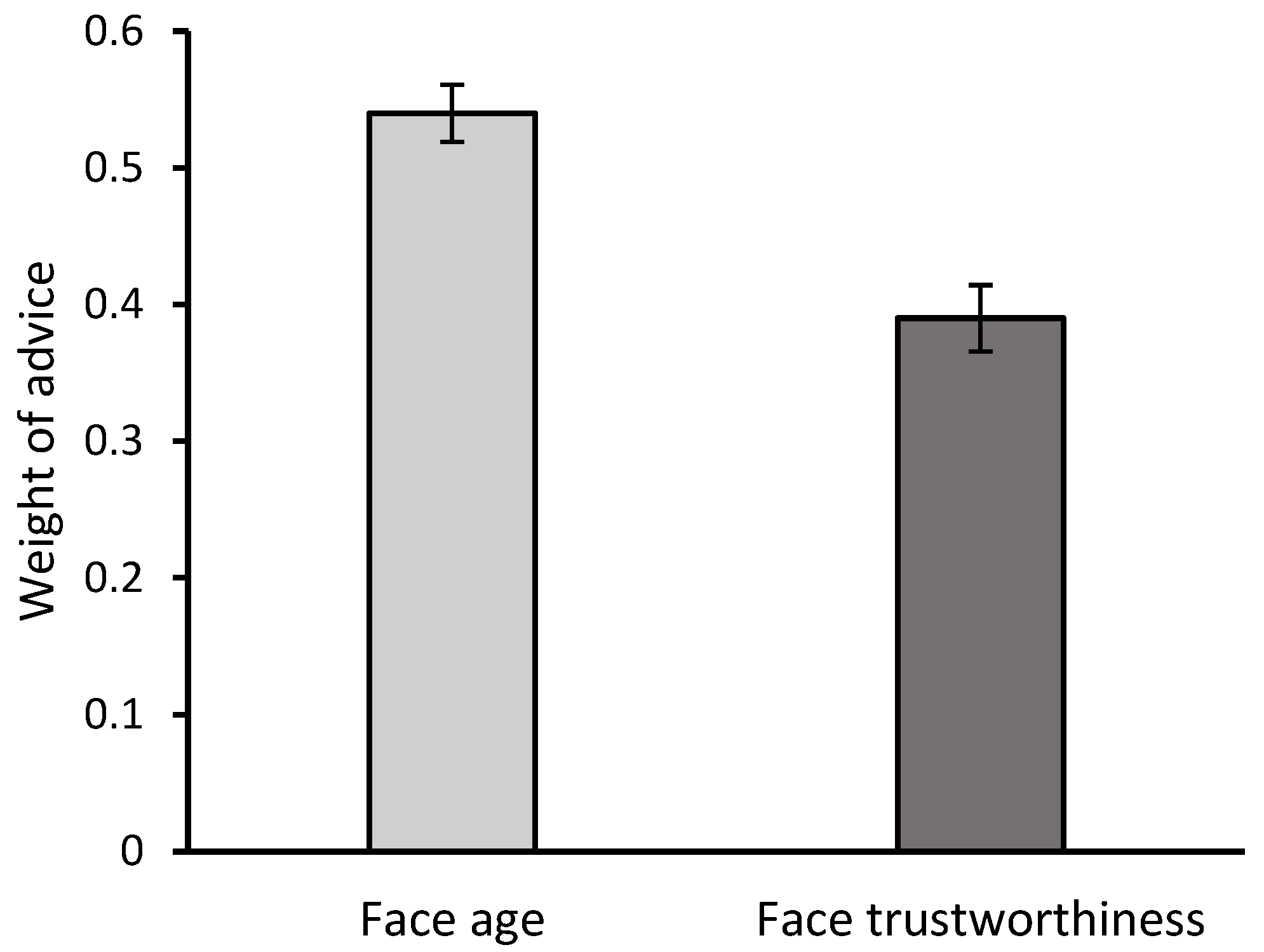

3.1. Weight of Advice

3.2. Correlations

3.3. Perceived Difficulty and Confidence

3.4. Actual Difficulty

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Allan, K., Azcona, J., Sripada, S., Leontidis, G., Sutherland, C. A. M., Phillips, L. H., & Martin, D. (2025). Stereotypical bias amplification and reversal in an experimental model of human interaction with generative artificial intelligence. Royal Science Open Society, 12, 241472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bailey, P. E., Ebner, N. C., Moustafa, A. A., Phillips, J. R., Leon, T., & Weidemann, G. (2021). The weight of advice in older age. Decision, 8(2), 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, P. E., Leon, T., Ebner, N. C., Moustafa, A. A., & Weidemann, G. (2023). A meta-analysis of the weight of advice in decision-making. Current Psychology, 42(28), 24516–24541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonaccio, S., & Dalal, R. S. (2006). Advice taking and decision-making: An integrative literature review, and implications for the organizational sciences. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 101(2), 127–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebner, N. C., Riediger, M., & Lindenberger, U. (2010). FACES—A database of facial expressions in young, middle-aged, and older women and men: Development and validation. Behavior Research Methods, 42(1), 351–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hardy, M. D., Thompson, B. D., Krafft, P. M., & Griffiths, T. L. (2023). Resampling reduces bias amplification in experimental social networks. Nature Human Behaviour, 7, 2084–2098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, R., Chesney, T., Chuah, S.-H., Kock, F., & Larner, J. (2020). Demonstrability, difficulty and persuasion: An experimental study of advice taking. Journal of Economic Psychology, 76, 102215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaeger, B., Todorov, A. T., Evans, A. M., & van Beest, I. (2020). Can we reduce facial biases? Persistent effects of facial trustworthiness on sentencing decisions. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 90, 104004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, R. S., Mileva, M., & Ritchie, K. L. (2018). Inter-rater agreement in trait judgements from faces. PLoS ONE, 13(8), e0202655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larrick, R. P., & Soll, J. B. (2006). Intuitions about combining opinions: Misappreciation of the averaging principle. Management Science, 52(1), 111–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laughlin, P. R. (1980). Social combination processes of copperative problem-solving groups on verbal intellective tasks. In M. Fishbein (Ed.), Progress in Social Psychology (pp. 127–155). Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Laughlin, P. R., & Ellis, A. L. (1986). Demonstrability and social combination processes on mathematical intellective tasks. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 22(3), 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoodi, A., Bang, D., Olsen, K., Zhao, Y. A., Shi, Z., Broberg, K., Safavi, S., Han, S., Ahmadabadi, M. N., Frith, C. D., Roepstorff, A., Rees, G., & Bahrami, B. (2015). Equality bias impairs collective decision-making across cultures. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 112(12), 3835–3840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mannes, A. E. (2009). Are we wise about the wisdom of crowds? The use of group judgments in belief revision. Management Science, 55(8), 1267–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meshi, D., Biele, G., Korn, C. W., & Heekeren, H. R. (2012). How expert advice influences decision making. PLoS ONE, 7(11), e49748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pehlivanoglu, D., Lin, T., Lighthall, N. R., Heemskerk, A., Harber, A., Wilson, R. C., Turner, G. R., Spreng, R. N., & Ebner, N. C. (2023). Facial trustworthiness perception across the adult life span. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 78(3), 434–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raven, J., Raven, J. C., & Court, J. H. (1998). Manual for raven’s progressive matrices and vocabulary scales. Oxford Psychologists Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schultze, T., Mojzisch, A., & Schulz-Hardt, S. (2017). On the inability to ignore useless advice. Experimental Psychology, 64(3), 170–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- See, K. E., Morrison, E. W., Rothman, N. B., & Soll, J. B. (2011). The detrimental effects of power on confidence, advice taking, and accuracy. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 116(2), 272–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherman, S. J., Presson, C. C., & Chassin, L. (1984). Mechanisms underlying the false consensus effect: The special role of threats to the self. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 10(1), 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sniezek, J. A., & Buckley, T. (1995). Cueing and cognitive conflict in judge-advisor decision making. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 62(2), 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatel, C. E., Tidler, Z. R., & Ackerman, P. L. (2022). Process differences as a function of test modifications: Construct validity of Raven’s advanced progressive matrices under standard, abbreviated and/or speeded conditions—A meta-analysis. Intelligence, 90, 101604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Swol, L. M. (2011). Forecasting another’s enjoyment versus giving the right answer: Trust, shared values, task effects, and confidence in improving the acceptance of advice. International Journal of Forecasting, 27(1), 103–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X., & Du, X. (2018). Why does advice discounting occur? The combined roles of confidence and trust. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 2381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wechsler, D. (2008). Wechsler adult intelligence scale-fourth edition: Administration and scoring manual. NCS Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Yaniv, I. (2004). Receiving other people’s advice: Influence and benefit. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 93(1), 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaniv, I., & Kleinberger, E. (2000). Advice taking in decision making: Egocentric discounting and reputation formation. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 83(2), 260–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Working memory | - | |||||||||

| 2. Fluid intelligence | 0.294 *** | - | ||||||||

| Age | ||||||||||

| 3. Weight of advice | 0.041 | −0.116 | - | |||||||

| 4. Perceived difficulty | 0.082 | 0.007 | 0.159 * | - | ||||||

| 5. Actual difficulty | −0.063 | −0.104 | 0.369 *** | 0.306 *** | - | |||||

| 6. Confidence | 0.095 | −0.055 | −0.061 | −0.257 *** | −0.029 | - | ||||

| Trustworthiness | ||||||||||

| 7. Weight of advice | −0.015 | −0.201 ** | 0.596 *** | 0.058 | 0.116 | −0.062 | - | |||

| 8. Perceived difficulty | −0.009 | 0.065 | 0.184 * | 0.300 *** | 0.001 | −0.362 *** | 0.190 * | - | ||

| 9. Actual difficulty | −0.225 * | −0.003 | −0.006 | 0.019 | 0.102 | 0.010 | −0.162 * | −0.019 | - | |

| 10. Confidence | −0.064 | −0.062 | −0.114 | −0.428 *** | −0.290 *** | 0.327 *** | −0.028 | −0.201 ** | 0.049 | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Phillips, J.R.; Weidemann, G.; Ebner, N.C.; Bailey, P.E. Advice-Taking for Objective Face Age Estimates Relative to Subjective Face Trustworthiness Estimates. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 809. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060809

Phillips JR, Weidemann G, Ebner NC, Bailey PE. Advice-Taking for Objective Face Age Estimates Relative to Subjective Face Trustworthiness Estimates. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(6):809. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060809

Chicago/Turabian StylePhillips, Joseph R., Gabrielle Weidemann, Natalie C. Ebner, and Phoebe E. Bailey. 2025. "Advice-Taking for Objective Face Age Estimates Relative to Subjective Face Trustworthiness Estimates" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 6: 809. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060809

APA StylePhillips, J. R., Weidemann, G., Ebner, N. C., & Bailey, P. E. (2025). Advice-Taking for Objective Face Age Estimates Relative to Subjective Face Trustworthiness Estimates. Behavioral Sciences, 15(6), 809. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060809