Academic Stress and Burnout Reduction Through Mandala-Coloring and Grit-Enhancing: School-Based Interventions for Adolescents

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Academic Stress and Burnout

1.2. Mindfulness-Based Interventions Tackle Academic Stress in School Settings

1.3. Building Grit as a Protective Factor

2. Materials and Methods

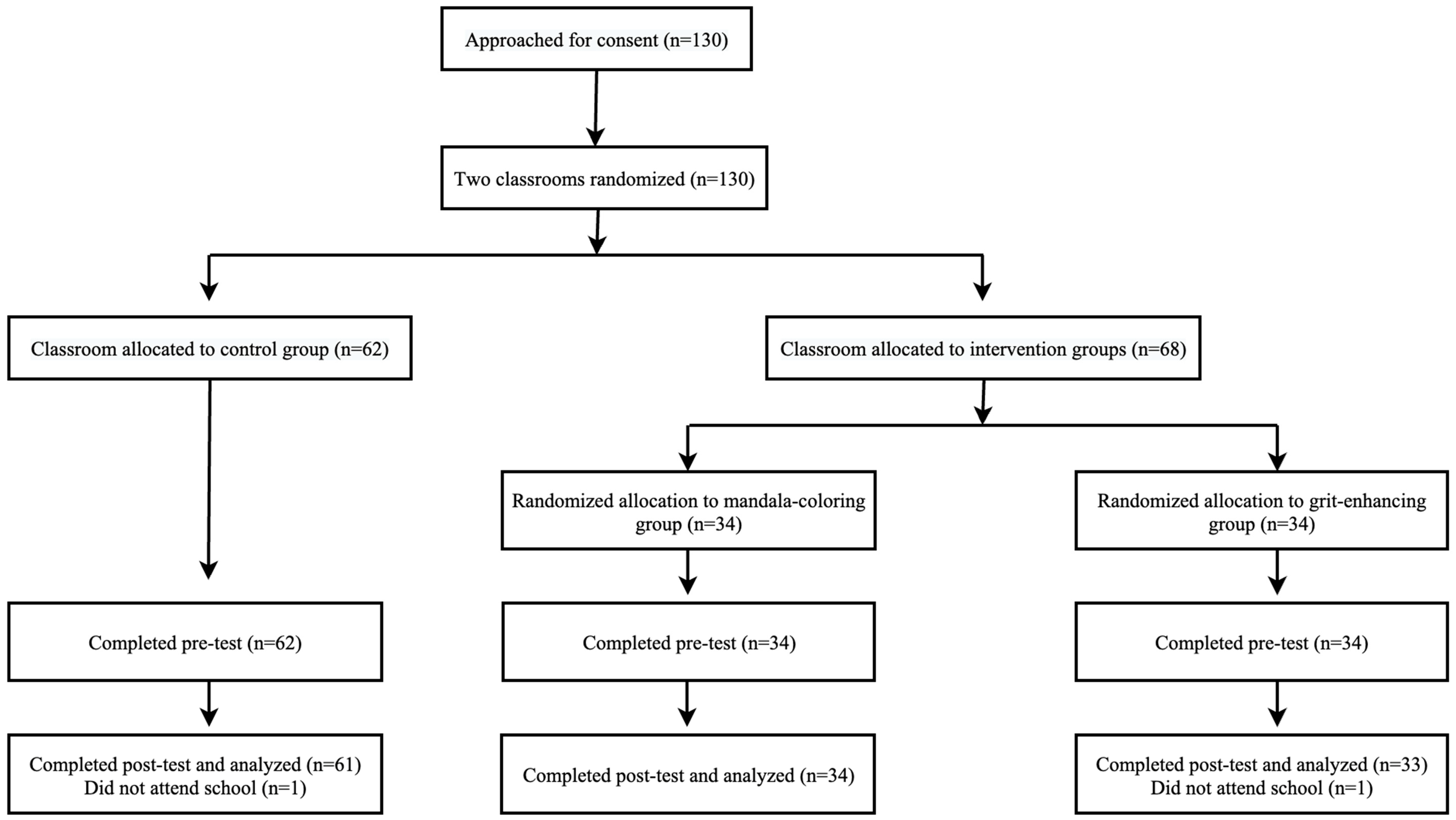

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Procedures

2.3.1. Mandala-Coloring Program

2.3.2. Grit-Enhancing Program

2.4. Measures

2.4.1. Academic Stress

2.4.2. Academic Burnout

2.4.3. Grit

2.5. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary Analyses

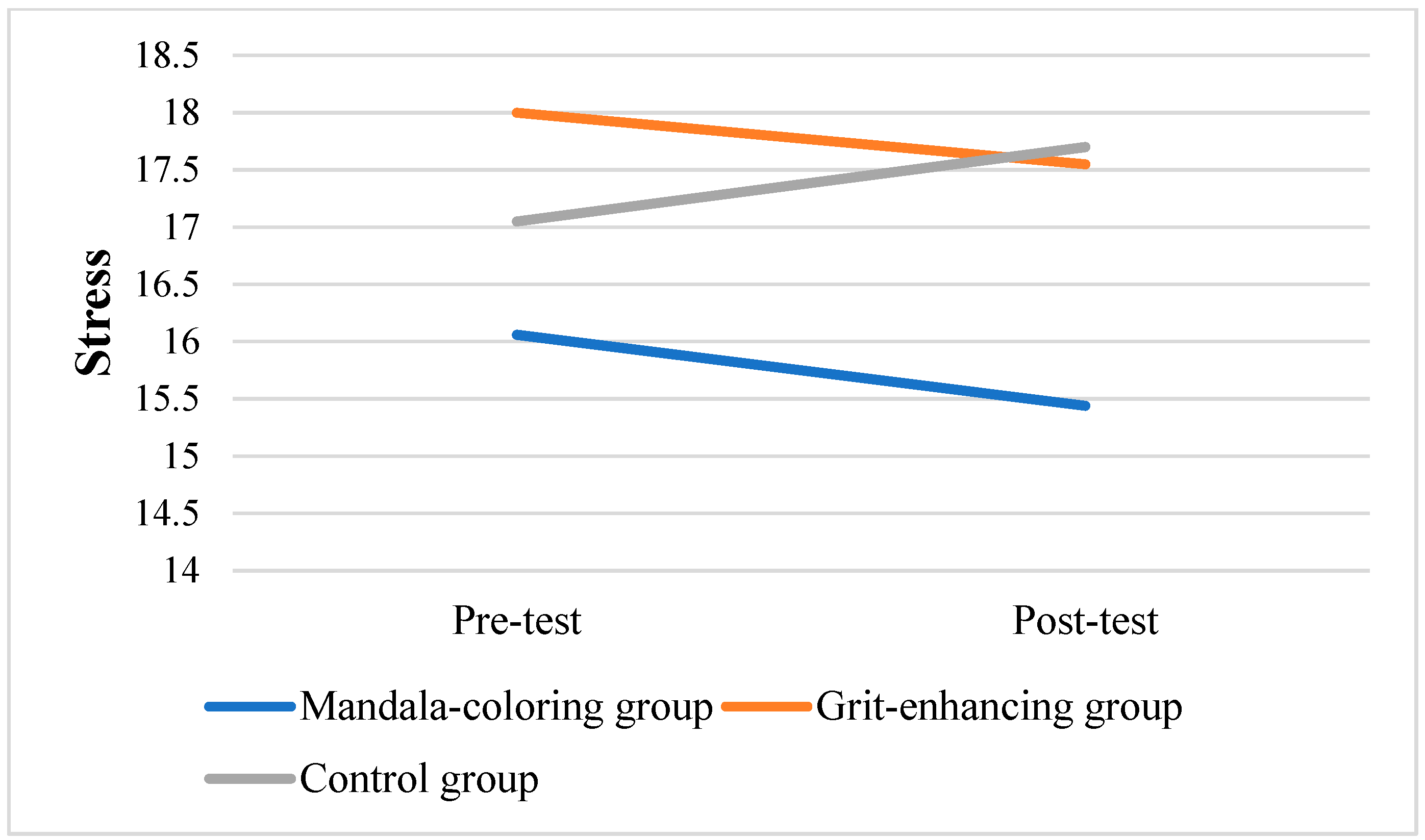

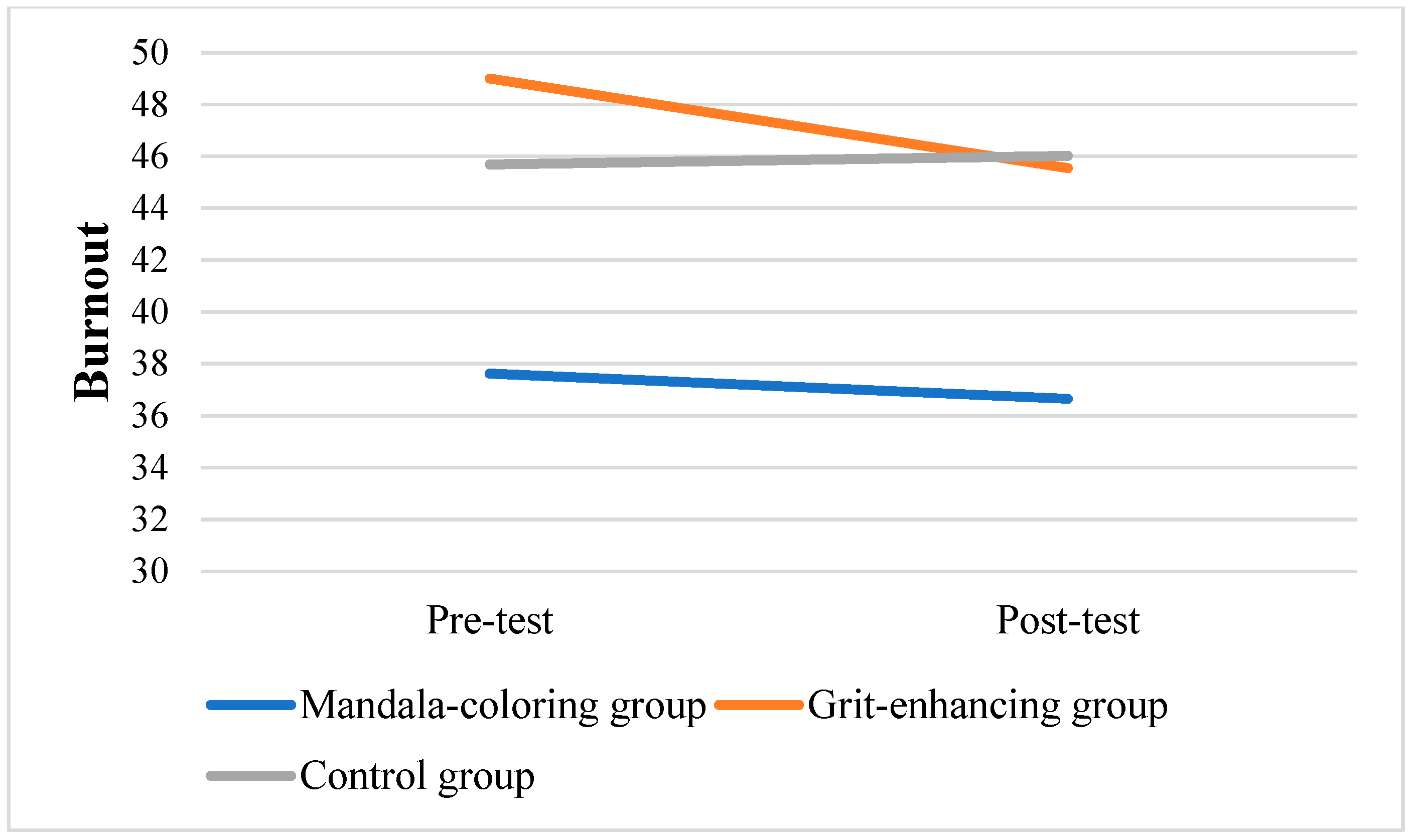

3.2. Effects of Interventions

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alan, S., Boneva, T., & Ertac, S. (2019). Ever failed, try again, succeed better: Results from a randomized educational intervention on grit. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 134(3), 1121–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amutio, A., Martínez-Taboada, C., Hermosilla, D., & Delgado, L. C. (2015). Enhancing relaxation states and positive emotions in physicians through a mindfulness training program: A one-year study. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 20(6), 720–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apriyana, R., Widianti, E., & Muliani, R. (2020). The influence of mandala pattern coloring therapy toward academic stress level on first grade students at nursing undergraduate study program. NurseLine Journal, 5(1), 186–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babouchkina, A., & Robbins, S. J. (2015). Reducing negative mood through mandala creation: A randomized controlled trial. Art Therapy, 32(1), 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2007). The job demands-resources model: State of the art. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 22(3), 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biggs, A. T., Seech, T. R., Johnston, S. L., & Russell, D. W. (2023). Psychological endurance: How grit, resilience, and related factors contribute to sustained effort despite adversity. The Journal of General Psychology, 151, 271–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birtwell, K., Williams, K., Van Marwijk, H., Armitage, C. J., & Sheffield, D. (2019). An exploration of formal and informal mindfulness practice and associations with wellbeing. Mindfulness, 10, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bresó, E., Schaufeli, W. B., & Salanova, M. (2011). Can a self-efficacy-based intervention decrease burnout, increase engagement, and enhance performance? A quasi-experimental study. Higher Education, 61(4), 339–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carsley, D., & Heath, N. L. (2018). Effectiveness of mindfulness-based colouring for test anxiety in adolescents. School Psychology International, 39(3), 251–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carsley, D., & Heath, N. L. (2019). Evaluating the effectiveness of a mindfulness coloring activity for test anxiety in children. The Journal of Educational Research, 112(2), 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carsley, D., Khoury, B., & Heath, N. L. (2018). Effectiveness of mindfulness interventions for mental health in schools: A comprehensive meta-analysis. Mindfulness, 9, 693–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J., Zhao, Y. Y., Wang, J., & Sun, Y. H. (2020). Academic burnout and depression of Chinese medical students in the pre-clinical years: The buffering hypothesis of resilience and social support. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 25(9), 1094–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curry, N. A., & Kasser, T. (2005). Can coloring mandalas reduce anxiety? Art Therapy, 22(2), 81–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czerwinski, N., Egan, H., Cook, A., & Mantzios, M. (2021). Teachers and mindful colouring to tackle burnout and increase mindfulness, resiliency and wellbeing. Contemporary School Psychology, 25(4), 535–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duckworth, A. L., Peterson, C., Matthews, M. D., & Kelly, D. R. (2007). Grit: Perseverance and passion for long-term goals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92(6), 1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emerson, L. M., De Diaz, N. N., Sherwood, A., Waters, A., & Farrell, L. (2020). Mindfulness interventions in schools: Integrity and feasibility of implementation. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 44(1), 62–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fariborz, N., Hadi, J., & Ali, T. N. (2019). Students’ academic stress, stress response and academic burnout: Mediating role of self-efficacy. Pertanika Journal of Social Sciences & Humanities, 27(4), 2441–2454. [Google Scholar]

- Fiorilli, C., De Stasio, S., Di Chiacchio, C., Pepe, A., & Salmela-Aro, K. (2017). School burnout, depressive symptoms and engagement: Their combined effect on student achievement. International Journal of Educational Research, 84, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong, J. S. Y., Hui, A. N. N., Ho, K. M., Chan, A. K. M., & Lee, A. (2022). Brief mindful coloring for stress reduction in nurses working in a Hong Kong hospital during COVID-19 pandemic: A randomized controlled trial. Medicine, 101(43), e31253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X. (2023). Academic stress and academic burnout in adolescents: A moderated mediating model. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1133706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gál, É., Ștefan, S., & Cristea, I. A. (2021). The efficacy of mindfulness meditation apps in enhancing users’ well-being and mental health related outcomes: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Journal of Affective Disorders, 279, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomes, A. R., Faria, S., & Gonçalves, A. M. (2013). Cognitive appraisal as a mediator in the relationship between stress and burnout. Work & Stress, 27(4), 351–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, A. A., & Kinchen, E. V. (2021). The effects of mindfulness meditation on stress and burnout in nurses. Journal of Holistic Nursing, 39(4), 356–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2009). The factorial validity of the Maslach Burnout Inventory–student survey in China. Psychological Reports, 105(2), 394–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, M. H., & Nam, J. K. (2021). Enhancing grit: Possibility and intervention strategies. In L. E. van Zyl, C. Olckers, & L. van der Vaart (Eds.), Multidisciplinary perspectives on grit (pp. 126–136). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Ireland, M. J., Clough, B., Gill, K., Langan, F., O’Connor, A., & Spencer, L. (2017). A randomized controlled trial of mindfulness to reduce stress and burnout among intern medical practitioners. Medical Teacher, 39(4), 409–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabat-Zinn, J. (2003). Mindfulness-based interventions in context: Past, present, and future. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 10(2), 144–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabat-Zinn, J., & Hanh, T. N. (2009). Full catastrophe living: Using the wisdom of your body and mind to face stress, pain, and illness. Delta. [Google Scholar]

- Kenny, D. A. (1979). Correlation and causality. Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C., Zhang, L. J., & Jiang, G. (2021). Conceptualisation and measurement of foreign language learning burnout among Chinese EFL students. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 45, 906–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J., Zhao, Y., Kong, F., Du, S., Yang, S., & Wang, S. (2018). Psychometric assessment of the short grit scale among Chinese adolescents. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 36(3), 291–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X. (2019). Effect of a mindfulness-based intervention program on comprehensive mental health problems of Chinese undergraduates. Community Mental Health Journal, 55(7), 1179–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., & Lu, Z. (2012). Chinese high school students’ academic stress and depressive symptoms: Gender and school climate as moderators. Stress and Health, 28(4), 340–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C., & Jackson, S. E. (1981). The measurement of experienced burnout. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 2(2), 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, A., Aghamirmohammadali, Z., Shabahang, R., Bagheri Sheykhangafshe, F., & Savabi Niri, V. (2023). Effectiveness of grit program on capacity of sustaining effort and interest for long-term purposes, mental toughness, and self-efficacy of students: An interventional study. Quarterly Journal of Child Mental Health, 9(4), 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosanya, M. (2021). Buffering academic stress during the COVID-19 pandemic related social isolation: Grit and growth mindset as protective factors against the impact of loneliness. International Journal of Applied Positive Psychology, 6(2), 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orosz, G., Péter-Szarka, S., Bőthe, B., Tóth-Király, I., & Berger, R. (2017). How not to do a mindset intervention: Learning from a mindset intervention among students with good grades. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, D., Tsukayama, E., Yu, A., & Duckworth, A. L. (2020). The development of grit and growth mindset during adolescence. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 198, 104889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prazak, M., Critelli, J., Martin, L., Miranda, V., Purdum, M., & Powers, C. (2012). Mindfulness and its role in physical and psychological health. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being, 4(1), 91–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reed, D. J. (2016). Coping with occupational stress: The role of optimism and coping flexibility. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 9, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W. B., Martinez, I. M., Pinto, A. M., Salanova, M., & Bakker, A. B. (2002). Burnout and engagement in university students: A cross-national study. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 33(5), 464–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuver, K. J., & Lewis, B. A. (2016). Mindfulness-based yoga intervention for women with depression. Complementary Therapies in Medicine, 26, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segal, Z., Williams, M., & Teasdale, J. (2018). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression. Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Shafiee Rad, H., & Jafarpour, A. (2023). Effects of well-being, grit, emotion regulation, and resilience interventions on l2 learners’ writing skills. Reading & Writing Quarterly, 39(3), 228–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shankar, N. L., & Park, C. L. (2016). Effects of stress on students’ physical and mental health and academic success. International Journal of School & Educational Psychology, 4(1), 5–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigmundsson, H., & Hauge, H. (2023). I CAN intervention to increase grit and self-efficacy: A pilot study. Brain Sciences, 14(1), 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, Y., & Lindquist, R. (2015). Effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction on depression, anxiety, stress and mindfulness in Korean nursing students. Nurse Education Today, 35(1), 86–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y., Yang, F., Sznajder, K., & Yang, X. (2020). Sleep quality as a mediator in the relationship between perceived stress and job burnout among Chinese nurses: A structural equation modeling analysis. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 566196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suyi, Y., Meredith, P., & Khan, A. (2017). Effectiveness of mindfulness intervention in reducing stress and burnout for mental health professionals in Singapore. Explore, 13(5), 319–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, J. B., & Yates, S. (2011). Academic expectations as sources of stress in Asian students. Social Psychology of Education, 14, 389–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L., Zhang, F., Yin, R., & Fan, Z. (2021). Effect of interventions on learning burnout: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 645662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X., Upadyaya, K., & Salmela-Aro, K. (2021). School burnout and psychosocial problems among adolescents: Grit as a resilience factor. Journal of Adolescence, 86, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teuber, Z., Nussbeck, F. W., & Wild, E. (2021). The bright side of grit in burnout-prevention: Exploring grit in the context of demands-resources model among Chinese high school students. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 52, 464–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Vennet, R., & Serice, S. (2012). Can coloring mandalas reduce anxiety? A replication study. Art Therapy, 29(2), 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Loon, A. W. G., Creemers, H. E., Okorn, A., Vogelaar, S., Miers, A. C., Saab, N., Westenberg, P. M., & Asscher, J. J. (2022). The effects of school-based interventions on physiological stress in adolescents: A meta-analysis. Stress and Health, 38(2), 187–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J. L., Rost, D. H., Qiao, R. J., & Monk, R. (2020). Academic stress and smartphone dependence among Chinese adolescents: A moderated mediation model. Children and Youth Services Review, 118, 105029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zappala-Piemme, K. E., Sturman, E. D., Brannigan, G. G., & Brannigan, M. J. (2023). Building mental toughness: A middle school intervention to increase grit, locus of control, and academic performance. Psychology in the Schools, 60(8), 2975–2990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D., Lee, E. K., Mak, E. C., Ho, C. Y., & Wong, S. Y. (2021). Mindfulness-based interventions: An overall review. British Medical Bulletin, 138(1), 41–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, X., Selman, R. L., & Haste, H. (2015). Academic stress in Chinese schools and a proposed preventive intervention program. Cogent Education, 2(1), 1000477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X., Haegele, J. A., Liu, H., & Yu, F. (2021). Academic stress, physical activity, sleep, and mental health among Chinese adolescents. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(14), 7257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Session | Mandala-Coloring Group | Grit-Enhancing Group |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Choose a mandala to color by yourself | Topic: Mindset Brief introduction: a short quiz to test one’s mindset; introduce the concept of mindsets through a video about growth mindset and fixed mindset (5 min); compare two types of mindsets in terms of characteristics; use a brainstorming game to further reinforce different concepts of thinking patterns: How would individuals with different mindsets think and behave in different scenarios? Summarize. |

| 2 | Choose a mandala to color by yourself | Topic: Mindset Play the game “Words spelling contest” to introduce the theme of brain’s ability to develop; read the article “You Can Grow Your Intelligence” and discuss in groups: What have you learned from this article? What aspect of growth mindset do you find most interesting after two sessions? Summarize. |

| 3 | Choose a mandala to color by yourself | Topic: Power of failure Introduce the concept of failure through a word guessing game; review the words that you failed to guess correctly, and discuss how to define failure; reflect and write about a past experience of failure, share the experience in pairs, and then discuss: How did you overcome this failure/setback? Did this failure have any positive impact on you? Learn about Michael Jordan’s example of “learning from failure.” Summarize. |

| 4 | Choose a mandala to color by yourself | Topic: SMART goal setting Recall this year’s New Year resolutions and have you accomplished yet; share a short story highlighting goal setting; understand what SMART (specific, measurable, actionable, relevant, time-bound) goals are through a video; individually reflect and set a new goal (in any area, such as learning a new skill, maintaining a fitness routine, obtaining better grades in the next exam, etc.), and share. Summarize |

| 5 | Choose a mandala to color by yourself | Topic: The role of effort and self-regulation Introduce the importance of effort through a card stacking game; introduce the marshmallow experiment and watch a video; reflect on the purpose of this experiment; discuss the differences between children who were able to resist the temptation and those who were not. Review the SMART goal setting in the previous class and discuss how to use effort and self-control to achieve your goals. Summarize. |

| 6 | Choose a mandala to color by yourself | Topic: Emotion regulation Introduce how we perceive and process emotions, and how mandala drawing can help us manage emotions and stress; distribute one mandala drawing, finish it within 20 min. Summarize. |

| Variables | Mandala-Coloring Group (N = 34) | Grit-Enhancing Group (N = 33) | Control Group (N = 61) | Test | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |||

| Gender | χ2(2) = 0.20 | 0.99 | ||||||

| Female | 14 | 41.2 | 14 | 42.4 | 26 | 42.6 | ||

| Male | 20 | 58.8 | 19 | 57.6 | 35 | 57.4 | ||

| Parents’ income (RMB) | χ2(8) = 8.73 | 0.37 | ||||||

| <3500 | 7 | 20.6 | 7 | 21.2 | 13 | 21.3 | ||

| 3500~7000 | 20 | 58.8 | 16 | 48.5 | 28 | 46.0 | ||

| 7000~10,000 | 6 | 17.7 | 7 | 21.2 | 17 | 27.8 | ||

| 10,000~15,000 | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 9.1 | 3 | 4.9 | ||

| ≥15,000 | 1 | 2.9 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | ||

| Parents’ education level | χ2(6) = 6.73 | 0.35 | ||||||

| Middle school graduated | 24 | 70.6 | 27 | 81.8 | 44 | 72.1 | ||

| High school graduated | 6 | 17.6 | 5 | 15.2 | 14 | 30.0 | ||

| Bachelor’s degree | 2 | 5.9 | 1 | 3.0 | 3 | 4.9 | ||

| Master’s degree | 2 | 5.9 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | ||

| Age (Mean ± SD) | 13.65 ± 0.69 | 13.42 ± 0.56 | 13.41 ± 0.53 | F(2) = 1.98 | 0.14 | |||

| Variable | Groups | F | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mandala-Coloring Group | Grit-Enhancing Group | Control Group | |||

| Stress | 16.06 ± 2.73 | 18.00 ± 3.57 | 17.05 ± 3.37 | 2.858 | 0.061 |

| Burnout | 37.62 ± 13.16 | 49.00 ± 19.89 | 45.69 ± 20.87 | 3.317 | 0.039 |

| Grit | 24.18 ± 4.13 | 22.36 ± 4.54 | 23.93 ± 5.16 | 1.519 | 0.223 |

| Variable | Mandala-Coloring Group | Grit-Enhancing Group | Control Group | F | p | η2p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | ||||

| Stress | 16.06 ± 2.73 | 15.44 ± 2.41 | 18.00 ± 3.57 | 17.55 ± 3.54 | 17.05 ± 3.37 | 17.70 ± 4.15 | 5.741 | 0.004 | 0.085 |

| Burnout | 37.62 ± 13.16 | 36.65 ± 12.47 | 49.00 ± 19.89 | 45.55 ± 20.37 | 45.69 ± 20.87 | 46.02 ± 22.25 | 1.150 | 0.320 | 0.018 |

| Grit | 24.18 ± 4.13 | 24.68 ± 4.39 | 22.36 ± 4.54 | 25.21 ± 5.22 | 23.93 ± 5.16 | 24.36 ± 6.85 | 1.794 | 0.171 | 0.028 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fan, X.; Hui, A.N.N. Academic Stress and Burnout Reduction Through Mandala-Coloring and Grit-Enhancing: School-Based Interventions for Adolescents. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 439. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15040439

Fan X, Hui ANN. Academic Stress and Burnout Reduction Through Mandala-Coloring and Grit-Enhancing: School-Based Interventions for Adolescents. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(4):439. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15040439

Chicago/Turabian StyleFan, Xuening, and Anna Na Na Hui. 2025. "Academic Stress and Burnout Reduction Through Mandala-Coloring and Grit-Enhancing: School-Based Interventions for Adolescents" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 4: 439. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15040439

APA StyleFan, X., & Hui, A. N. N. (2025). Academic Stress and Burnout Reduction Through Mandala-Coloring and Grit-Enhancing: School-Based Interventions for Adolescents. Behavioral Sciences, 15(4), 439. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15040439