Quantity-Sourced or Quality-Sourced? The Impact of Word-of-Mouth Recommendations on China Rural Residents’ Online Purchase Intention: The Chain Mediating Roles of Social Distance and Perceived Value

Abstract

1. Introduction

- What are the effects of different WOM recommendations on the rural residents’ OPI?

- Do SD and PV affect the rural residents’ OPI?

- Do SD and PV play a chain mediating role in WOM recommendation types and OPI?

2. Theoretical Background and Research Hypothesis

2.1. Social Tie Strength Theory

2.2. WOM Recommendations and Rural Residents’ Online Purchase Intention

2.3. WOM Recommendations and Social Distance

2.4. WOM Recommendations and Perceived Value

2.5. Social Distance and Purchase Intention

2.6. Perceived Value and Purchase Intention

2.7. Social Distance and Perceived Value

2.8. The Chain Mediating Effect of SD and PV

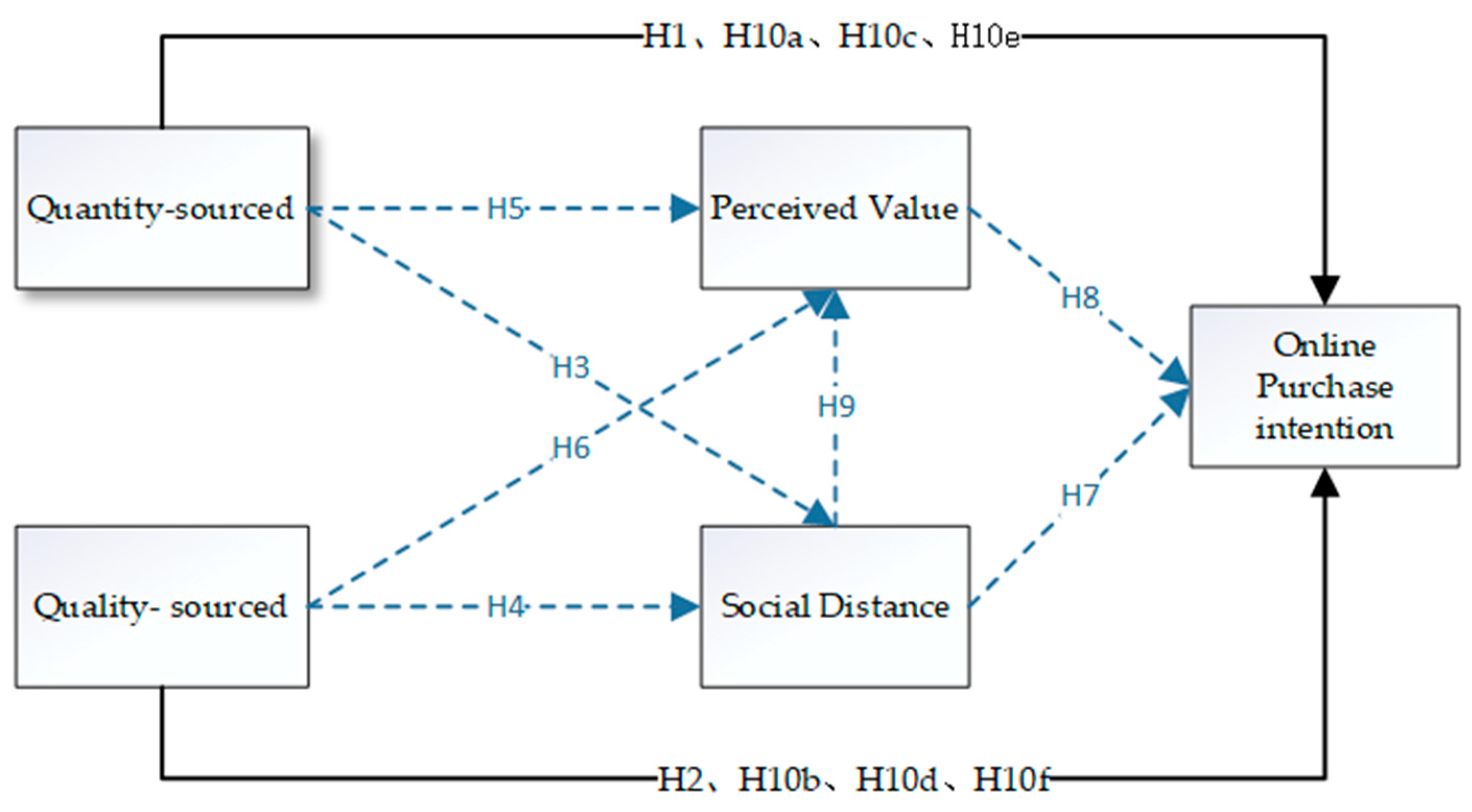

2.9. Theoretical Framework

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Participants and Procedure

3.2. Variable Measurement

4. Results

4.1. Respondent Demographic Characteristics

4.2. Reliability and Validity Analysis

4.3. Discriminant Validity Analysis

4.4. Co-Linear Analysis

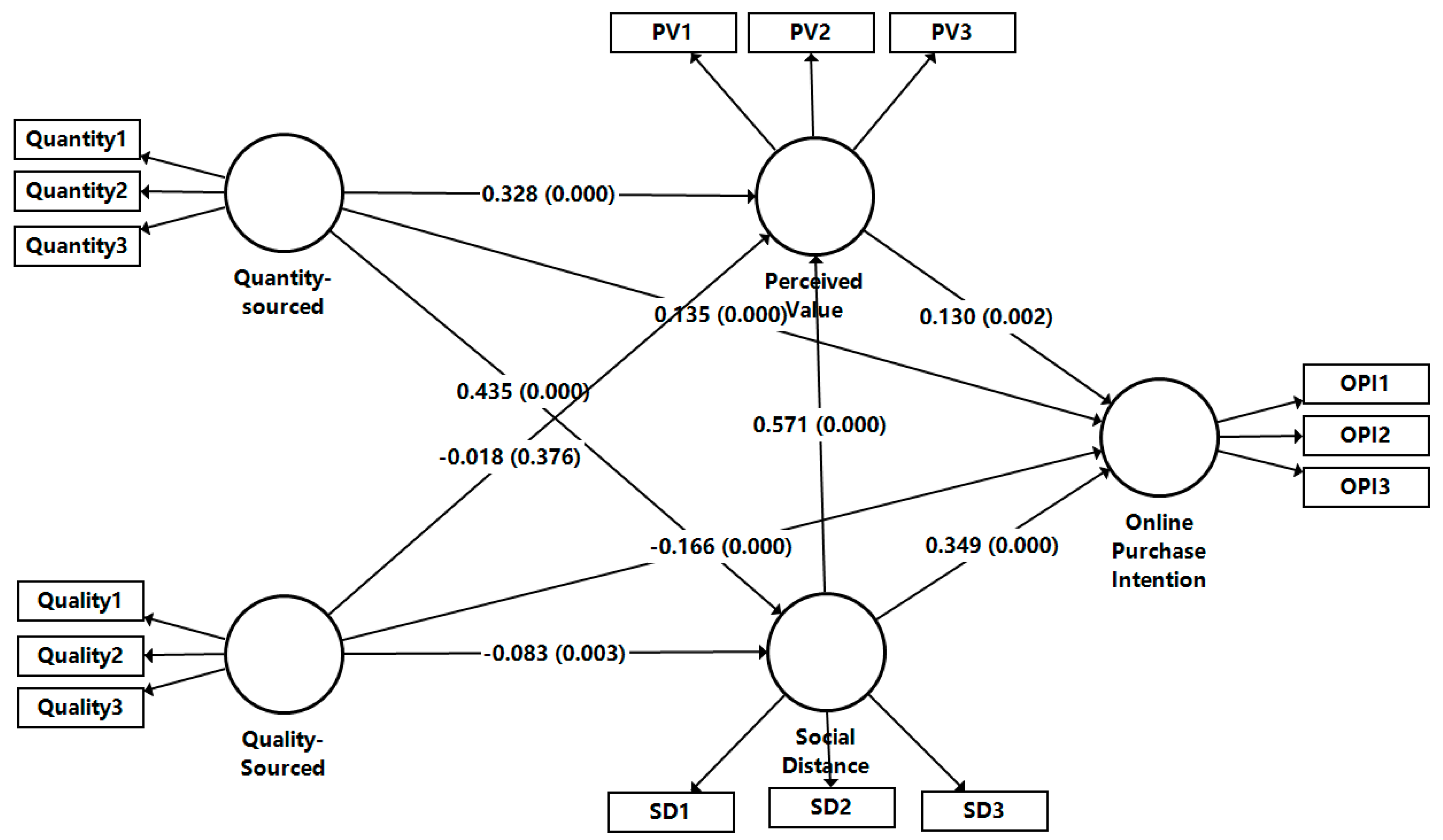

4.5. Path Analysis

5. Discussion

6. Implications

6.1. Theoretical Implications

6.2. Practical Implications

7. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abou-Warda, S. H. (2016). The impact of social relationships on online word-of-mouth and knowledge sharing in social network sites: An empirical study. International Journal of Online Marketing (IJOM), 6(1), 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akerlof, G. A. (1997). Social distance and social decisions. Econometrica: Journal of the Econometric Society, 65, 1005–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, J., Mehmood, K., Mian, A. M., & Karim, P. A. (2025). From traditional advertising to digital marketing: Exploring electronic word of mouth through a theoretical lens in the hospitality and tourism industry. Global Knowledge, Memory and Communication, 74(5–6), 1973–1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anoop, B., Vinod, K., Ajay, S., & Anupam, N. (2022). Analyzing the mediating effect of consumer online purchase intention in online shopping of domestic appliances. Journal of Information and Optimization Sciences, 43(7), 1499–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arumugam, T., Hameed, S. S., & Sanjeev, M. A. (2023). Buyer behaviour modelling of rural online purchase intention using logistic regression. International Journal of Management and Enterprise Development, 22(2), 139–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyari, H., & Hashem, T. (2025). The role of artificial intelligence in personalizing social media marketing strategies for enhanced customer experience. Behavioral Sciences, 15(5), 700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlton, S. R., Gossett, B. D., & Charlton, V. A. (2012). Effect of delay and social distance on the perceived value of social interaction. Behavioural processes, 89(1), 23–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C., Zhang, D., Zhang, F., & Gao, H. (2023). Is professional reputation better than public reputation? A study on the influence of different types of reputation on customers’ purchase intentions. Nankai Business Review, 26(4), 25–37. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, S. (2019). The application of social capital embedded in social networks: From social network platform to social commerce platform. The Journal of Internet Electronic Commerce Resarch, 19(4), 23–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuong, D. T. (2024). Examining how electronic word-of-mouth information influences customers’ purchase intention: The moderating effect of perceived risk on e-commerce platforms. SAGE Open, 14(4), 21582440241309408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, M., & Ramalingam, M. (2023). To praise or not to praise-Role of word of mouth in food delivery apps. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 74, 103408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deepak, V., Prem, P. D., Abhishek, B., Vijay, P., Yogesh, D., & Manilo, D. G. (2023). A meta-analysis of antecedents and consequences of eWOM credibility: Investigation of moderating role of culture and platform type. Journal of Business Research, 154, 113292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dege, L., Bin, H., Ruan, F., Xiaojun, H., & Gaoqiang, L. (2024). How social media sharing drives consumption intention: The role of social media envy and social comparison orientation. BMC Psychology, 12(1), 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Keyzer, F., Dens, N., & De Pelsmacker, P. (2019). The impact of relational characteristics on consumer responses to word of mouth on social networking sites. International Journal of Electronic Commerce, 23(2), 212–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinoza, J. L., Ayensa, E. J., Milon, A. G., & Pascual, C. O. (2024). Why do you want an organic coffee? Self-care vs. world-care: A new SOR model approach to explain organic product purchase intentions of Spanish consumers. Food Quality and Preference, 118, 105203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faraji-Rad, A., Samuelsen, B. M., & Warlop, L. (2015). On the persuasiveness of similar others: The role of mentalizing and the feeling of certainty. Journal of Consumer Research, 42(3), 458–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J. H. H., & Guo, T. (2025). Not only cosmopolitan but also local: Fei Xiaotong’s social surveys in the 1930s and 1940s. International Sociology, 40(2), 287–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filieri, R., McLeay, F., Tsui, B., & Lin, Z. (2018). Consumer perceptions of information helpfulness and determinants of purchase intention in online consumer reviews of services. Information & Management, 55(8), 956–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granovetter, M. S. (1973). The strength of weak ties. American Journal of Sociology, 78(6), 1360–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendriks, F., Kienhues, D., & Bromme, R. (2015). Measuring laypeople’s trust in experts in a digital age: The Muenster Epistemic Trustworthiness Inventory (METI). PLoS ONE, 10(10), e0139309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Ortega, B. (2018). Don’t believe strangers: Online consumer reviews and the role of social psychological distance. Information & management, 55(1), 31–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilkenmeier, F., Bohndick, C., Bohndick, T., & Hilkenmeier, J. (2020). Assessing distinctiveness in multidimensional instruments without access to raw data–a manifest Fornell-Larcker criterion. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hipólito, F., Dias, Á., & Pereira, L. (2025). Influence of consumer trust, return policy, and risk perception on satisfaction with the online shopping experience. Systems, 13(3), 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, C., Choi, H., Choi, E. K., & Joung, H. W. (2025). Exploring customer perceptions of food delivery robots: A value-based model of perceived value, satisfaction, and their impact on behavioral intentions and word-of-mouth. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 34(4), 526–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, F., Xu, P., Deng, X., Zhou, J., Li, J., & Tao, D. (2006). Molecular mapping of a pollen killer gene S29 (t) in Oryza glaberrima and co-linear analysis with S22 in O. glumaepatula. Euphytica, 151, 273–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, N., Burtch, G., Hong, Y., & Polman, E. (2016). Effects of multiple psychological distances on construal and consumer evaluation: A field study of online reviews. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 26(4), 474–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, K., & Zhang, Q. (2018). Influence of parasocial relationship between digital celebrities and their followers on followers’ purchase and electronic word-of-mouth intentions, and persuasion knowledge. Computers in Human Behavior, 87, 155–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyegyu, O. H. J. L. (2019). When do people verify and share health rumors on social media? The effects of message importance, health anxiety, and health literacy. Journal of Health Communication, 24(11), 837–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jucks, R., & Thon, F. M. (2017). Better to have many opinions than one from an expert? Social validation by one trustworthy source versus the masses in online health forums. Computers in Human Behavior, 70, 375–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakayali, N. (2009). Social distance and affective orientations 1. In Sociological forum. Wiley Online Library. [Google Scholar]

- Keh, H. T., & Sun, J. (2018). The differential effects of online peer review and expert review on service evaluations: The roles of confidence and information convergence. Journal of Service Research, 21(4), 474–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kergoat, M., Lecuyer, C., & Meyer, T. (2025). The effect of risk on purchase confidence and subsequent purchase intention: The moderating role of product container haptic sensations. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 87, 104354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K., Zhang, M., & Li, X. (2008). Effects of temporal and social distance on consumer evaluations. Journal of Consumer Research, 35(4), 706–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruglanski, A. W., Jasko, K., Milyavsky, M., Chernikova, M., Webber, D., Pierro, A., & Di Santo, D. (2018). Cognitive consistency theory in social psychology: A paradigm reconsidered. Psychological Inquiry, 29(2), 45–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y., & Shan, B. (2025). The influence mechanism of green advertising on consumers’ purchase intention for organic foods: The mediating roles of green perceived value and green trust. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, 9, 1515792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H., Zhang, P., Cheng, H., Hasan, N., & Chiong, R. (2025). Impact of AI-generated virtual streamer interaction on consumer purchase intention: A focus on social presence and perceived value. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 85, 104290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, C., Wu, J., Shi, Y., & Xu, Y. (2014). The effects of individualism–collectivism cultural orientation on eWOM information. International Journal of Information Management, 34(4), 446–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Z. (2025). Key determinants of purchase intentions for geographical indication agricultural products: A hybrid PLS-SEM and ANN approach. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 84, 104209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najafabadiha, A., Wang, Y., Gholizadeh, A., Javanmardi, E., & Zameer, H. (2025). Fostering consumer engagement in online shopping: Assessment of environmental video messages in driving purchase intentions toward green products. Journal of Environmental Management, 373, 123637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T. T. T., Limbu, Y. B., Pham, L., & Zúñiga, M. Á. (2024). The influence of electronic word of mouth on green cosmetics purchase intention: Evidence from young Vietnamese female consumers. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 41(4), 406–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y. E., & Son, H. (2025). AI recommendation vs. crowdsourced recommendation vs. travel expert recommendation: The moderating role of consumption goal on travel destination decision. PLoS ONE, 20(3), e0318719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahira, D. N., Kristaung, R., Talib, F. E. A., & Mandagie, W. C. (2023). Electronic word-of-mouth model on customers’ online purchase intention with multi-group approach digital services. International Journal of Business Innovation and Research, 30(1), 68–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santamaría, C. Á., Gil, C. R., & Vega, A. V. R. (2024). The power of social commerce: Understanding the role of social word-of-mouth behaviors and flow experience on social media users’ purchase intention. SAGE Open, 14(3), 21582440241278452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafiq, R., Raza, I., & Zia-ur-Rehman, M. (2011). Analysis of the factors affecting customers’ purchase intention: The mediating role of perceived value. African Journal of Business Management, 5(26), 10577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, H. (2023). Research on digital literacy survey and promotion strategies of rural E-commerce under the perspective of digital economy—Taking Yiwu as an example. International Journal of Mathematics and Systems Science, 3(3), 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S., & Rehman, A. (2017). Impact of social relationships on electronic word of mouth in social networking sites: A study of Indian social network users. International Journal of Electronic Marketing and Retailing, 8(2), 93–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, M., & Wojnicki, A. C. (2014). Money talks… to online opinion leaders: What motivates opinion leaders to make social-network referrals? Journal of Advertising Research, 54(1), 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, P. D., Le, T. D., Nguyen, N. P., & Nguyen, U. T. (2024). The impact of source characteristics and parasocial relationship on electronic word-of-mouth influence: The moderating role of brand credibility. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, 36(11), 2813–2830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walther, J. B., Van Der Heide, B., Hamel, L. M., & Shulman, H. C. (2009). Self-generated versus other-generated statements and impressions in computer-mediated communication: A test of warranting theory using Facebook. Communication Research, 36(2), 229–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J., Pan, D., Zhao, Z., Liu, Y., Han, X., Gao, J., & Wang, M. (2023). The effect of inconsistent online reviews on customers’ purchase intention in e-commerce: A psychological distance perspective. Social Behavior and Personality, 51(3), 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., Ngai, E. W. T., & Li, K. (2024). Effects of sentiment quantity, dispersion, and dissimilarity on online review forwarding behavior: An empirical analysis. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 81, 103978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X., & Yuan, Z. (2023). Understanding the socio-cultural resilience of rural areas through the intergenerational relationship in transitional China: Case studies from Guangdong. Journal of Rural Studies, 97, 303–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, H., & Taylor, L. (2022). When do people believe, check, and share health rumors on social media? Effects of evidence type, health literacy, and health knowledge. Journal of Health Psychology, 28(7), 13591053221125992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X. (2019). How perceived social distance and trust influence reciprocity expectations and eWOM sharing intention in social commerce. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 119(4), 867–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X., Roy, S. K., Quazi, A., Nguyen, B., & Han, Y. (2017). Internet entrepreneurship and “the sharing of information” in an Internet-of-Things context:The role of interactivity, stickiness, e-satisfaction and word-of-mouth in online SMEs’ websites. Internet Research, 27(1), 74–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeithaml, V. A. (1988). Consumer perceptions of price, quality, and value: A means-end model and synthesis of evidence. Journal of marketing, 52(3), 2–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K., & Cheng, X. (2025). Determinants of consumers’ intentions to use smart home devices from the perspective of perceived value: A mixed SEM, NCA, and fsQCA study. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 87, 104399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M., & Xie, J. (2011). Effects of social and temporal distance on consumers’ responses to peer recommendations. Journal of Marketing Research, 48(3), 486–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y., Wang, L., Tang, H., & Zhang, Y. (2020). Electronic word-of-mouth and consumer purchase intentions in social E-commerce. Electronic Commerce Research and Applications, 41(prepublish), 100980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z., Elsabeh, M. H., Baudier, P., Renard, D., & Brem, A. (2024). Functional, hedonic, and social motivated consumer innovativeness as a driver of word-of-mouth in smart object early adoptions: An empirical examination in two product categories. International Journal of Technology Management, 95(1–2), 226–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C., Ling, S., & Cho, D. (2023). How social identity affects green food purchase intention: The serial mediation effect of green perceived value and psychological distance. Behavioral Sciences, 13(8), 664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | Measurement Items | Adopted From |

|---|---|---|

| Quantity-Sourced | Throughout electronic shopping decision processes, you are significantly more inclined to refer to your family’s recommendation. Throughout electronic shopping decision processes, you are significantly more inclined to refer to your relatives’, friends’, or neighbors’ recommendations. Throughout electronic shopping decision processes, you are significantly more inclined to the general public’s recommendation. | (Chen et al., 2023; Jucks & Thon, 2017) |

| Quality-Sourced | When making online shopping decisions, you show preference for the recommendations of salespersons. When making online shopping decisions, you show preference for the recommendations of online celebrities or stars. When making online shopping decisions, you show preference for the recommendations of industry experts. | (Chen et al., 2023; Hendriks et al., 2015) |

| Social Distance | I feel that the lifestyle of online shopping recommenders is similar to mine. I belong to the same social circle as those who frequently post online shopping recommendations. I am willing to actively establish social connections with those whom I trust in online shopping recommendations. | (Zheng et al., 2023) |

| Perceived Value | You can buy more cost-effective goods through online shopping. You can buy better quality goods through online shopping. You can purchase satisfactory goods or services through online shopping. | (Zhang & Cheng, 2025) |

| Online Purchase Intention | In the future, when you need something, you will tend to do online shopping. In the future, you will make more frequent online purchases. In the future, the amount of money you spend on online shopping will be greater. | (Najafabadiha et al., 2025) |

| Variables | Frequency | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 541 | 53.8 |

| Female | 464 | 46.2 | |

| Age | 18–30 | 190 | 18.9 |

| 31–45 | 243 | 24.2 | |

| 46–60 | 349 | 34.7 | |

| Over 65 | 223 | 22.2 | |

| Health Condition | Very unhealthy | 15 | 1.5 |

| Not very healthy | 32 | 3.2 | |

| Good | 143 | 14.3 | |

| Relatively healthy | 382 | 38 | |

| Very healthy | 433 | 43.1 | |

| Education | Primary school and below | 282 | 28.1 |

| Junior high school | 344 | 34.3 | |

| Technical secondary school or high school | 307 | 30.5 | |

| Junior college | 206 | 20.5 | |

| Undergraduate | 68 | 6.8 | |

| Postgraduate | 80 | 8.0 | |

| Annual Income | CNY 0–10,000 | 303 | 30.15 |

| CNY 10,001–50,000 | 547 | 54.43 | |

| CNY 50,001–100,000 | 120 | 11.94 | |

| Over CNY 100,000 | 35 | 3.48 |

| Constructs | Item | Factor Loading | Cronbach’s α | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quality-Sourced | Quality1 | 0.528 | 0.682 | 0.81 | 0.598 |

| Quality2 | 0.896 | ||||

| Quality3 | 0.845 | ||||

| Quantity-Sourced | Quantity1 | 0.834 | 0.654 | 0.808 | 0.585 |

| Quantity2 | 0.745 | ||||

| Quantity3 | 0.709 | ||||

| Social Distance | SD1 | 0.921 | 0.886 | 0.929 | 0.815 |

| SD2 | 0.912 | ||||

| SD3 | 0.874 | ||||

| Perceived Value | PV1 | 0.875 | 0.825 | 0.896 | 0.741 |

| PV2 | 0.883 | ||||

| PV3 | 0.824 | ||||

| Online Purchase Intention | OPI1 | 0.949 | 0.916 | 0.947 | 0.856 |

| OPI2 | 0.951 | ||||

| OPI3 | 0.874 |

| OPI | PV | Quality-Sourced | Quantity-Sourced | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OPI | 0.925 | ||||

| PV | 0.473 | 0.861 | |||

| Quality-Sourced | 0.37 | 0.579 | 0.774 | ||

| Quantity-Sourced | −0.22 | −0.091 | −0.045 | 0.765 | |

| SD | 0.518 | 0.716 | 0.438 | −0.102 | 0.903 |

| OPI | PV | Quality-Sourced | Quantity-Sourced | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OPI | |||||

| PV | 0.539 | ||||

| Quality-Sourced | 0.419 | 0.713 | |||

| Quantity-Sourced | 0.274 | 0.127 | 0.156 | ||

| SD | 0.571 | 0.835 | 0.468 | 0.121 |

| OPI | PV | Quality-Sourced | Quantity-Sourced | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OPI | |||||

| PV | 2.503 | ||||

| Quality-Sourced | 1.507 | 1.238 | 1.002 | ||

| Quantity-Sourced | 1.011 | 1.011 | 1.002 | ||

| SD | 2.064 | 1.249 |

| β | Standard Deviation | t | p | LLCI | ULCI | Decision | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1: Quantity-Sourced → OPI | 0.135 | 0.032 | 4.184 | 0.000 | 0.072 | 0.200 | Supported |

| H2: Quality-Sourced → OPI | −0.166 | 0.025 | 6.667 | 0.000 | −0.214 | −0.119 | Supported |

| H3: Quantity-Sourced → SD | 0.435 | 0.028 | 15.678 | 0.000 | 0.380 | 0.489 | Supported |

| H4: Quality-Sourced → SD | −0.083 | 0.028 | 2.925 | 0.003 | −0.141 | −0.029 | Supported |

| H5: Quantity-Sourced → PV | 0.328 | 0.026 | 12.539 | 0.000 | 0.276 | 0.378 | Supported |

| H6: Quality-Sourced → PV | −0.018 | 0.020 | 0.885 | 0.376 | −0.057 | 0.021 | Unsupported |

| H7: SD → OPI | 0.349 | 0.042 | 8.267 | 0.000 | 0.263 | 0.429 | Supported |

| H8: PV → OPI | 0.130 | 0.041 | 3.161 | 0.002 | 0.048 | 0.209 | Supported |

| H9: SD → PV | 0.571 | 0.021 | 27.722 | 0.000 | 0.531 | 0.611 | Supported |

| H10a: Quantity-Sourced → SD → OPI | 0.152 | 0.020 | 7.611 | 0.000 | 0.114 | 0.193 | Supported |

| H10b: Quality-Sourced → SD → OPI | −0.047 | 0.016 | 2.877 | 0.004 | −0.082 | −0.017 | Supported |

| H10c: Quantity-Sourced → PV → OPI | 0.043 | 0.014 | 3.052 | 0.002 | 0.015 | 0.070 | Supported |

| H10d: Quality-Sourced → PV → OPI | −0.002 | 0.003 | 0.803 | 0.422 | −0.009 | 0.003 | Unsupported |

| H10e: Quantity-Sourced → SD → PV → OPI | 0.043 | 0.014 | 3.052 | 0.002 | 0.012 | 0.053 | Supported |

| H10f: Quality-Sourced → SD → PV → OPI | −0.006 | 0.003 | 2.098 | 0.036 | −0.013 | −0.001 | Supported |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, C.; Guo, J. Quantity-Sourced or Quality-Sourced? The Impact of Word-of-Mouth Recommendations on China Rural Residents’ Online Purchase Intention: The Chain Mediating Roles of Social Distance and Perceived Value. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1661. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121661

Wang C, Guo J. Quantity-Sourced or Quality-Sourced? The Impact of Word-of-Mouth Recommendations on China Rural Residents’ Online Purchase Intention: The Chain Mediating Roles of Social Distance and Perceived Value. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(12):1661. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121661

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Changxu, and Jinyong Guo. 2025. "Quantity-Sourced or Quality-Sourced? The Impact of Word-of-Mouth Recommendations on China Rural Residents’ Online Purchase Intention: The Chain Mediating Roles of Social Distance and Perceived Value" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 12: 1661. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121661

APA StyleWang, C., & Guo, J. (2025). Quantity-Sourced or Quality-Sourced? The Impact of Word-of-Mouth Recommendations on China Rural Residents’ Online Purchase Intention: The Chain Mediating Roles of Social Distance and Perceived Value. Behavioral Sciences, 15(12), 1661. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121661