1. Introduction

Generative Artificial Intelligence (GenAI) has rapidly emerged as a transformative technology capable of reshaping how employees perform tasks, make decisions, and create value. Its potential to automate routine processes, augment complex reasoning, and accelerate knowledge work has fueled the promise of widespread organizational adoption. Yet, emerging evidence reveals that GenAI’s benefits are unevenly distributed across occupations and roles. For instance,

Brynjolfsson et al. (

2025) reported a 15% productivity increase among customer-support agents using AI, but these gains accrued primarily to less experienced workers, with minimal improvement observed in roles where task complexity is more prevalent. Such similar asymmetries across industries (

Handa et al., 2025) indicate that the benefits of GenAI are not solely determined by individual characteristics but by the structural features of work itself. The prior literature suggests that job characteristics may influence opportunities for meaningful human–AI interaction (

Przegalinska et al., 2025). Consequently, understanding the conditions under which GenAI complements or constrains employee performance requires shifting the analytical lens from merely personal adoption traits to the nature of the job as the contextual foundation for AI use. However, we still lack a clear understanding of when and how such job characteristics facilitate or constrain employees’ confidence in using GenAI and their subsequent adoption behavior.

Employees’ GenAI adoption decisions are not made in isolation. They unfold within the constraints and affordances of their work context. Job characteristics create the conditions under which individuals decide whether and how to integrate new technologies (

Venkatesh et al., 2003). Among these characteristics, job complexity has become a particularly salient determinant of technology use. Job complexity reflects “the extent to which a job entails autonomy or less routine and the extent to which it allows for decision latitude” (

Shalley et al., 2009, p. 493). It encompasses a range of skills required for effective task execution (

Morgeson & Humphrey, 2006). This complexity might shape performance outcomes and also contribute to how employees engage with intelligent technologies (

Bailey et al., 2019;

Q. Zhang et al., 2025). When job complexity provides an optimal level of technological assistance, employees gain frequent, meaningful opportunities to interact with GenAI, fostering confidence and learning through positive experiences. Conversely, when job complexity is either too low or too high, opportunities for productive human–AI interaction diminish, either because work is overly routine and easily automated or because it exceeds GenAI’s current capabilities, leading to frustration and diminished confidence. These dynamics suggest a nonlinear relationship between job complexity and employees’ confidence in using AI, or AI self-efficacy (

Almatrafi et al., 2024;

Bandura, 1997).

These observations reveal a joint empirical and theoretical puzzle. Empirically, recent work documents uneven benefits of generative AI across jobs and that the influence of job complexity on its use is inconsistent, with studies reporting positive, negative, and curvilinear effects (e.g.,

Brynjolfsson et al., 2025). Theoretically, however, prevailing technology adoption models largely treat task complexity and fit as monotonic drivers of utilization and do not specify how job design shapes the development of AI self-efficacy and readiness (e.g.,

Awa et al., 2017). As a result, existing frameworks are muted to explain why generative AI improves performance in some roles, has little effect in others, and may even undermine confidence and use in highly complex jobs. This empirical inconsistency therefore signals a deeper theoretical gap that our study seeks to address.

To address this joint empirical and theoretical puzzle, this study integrates the Task–Technology Fit (TTF) framework (

Goodhue & Thompson, 1995) as an overarching theoretical lens. TTF posits that technology adoption and performance depend on the alignment between task demands and technological capabilities. However, traditional TTF assumes static task–technology relationships, which may not hold for adaptive systems such as GenAI (

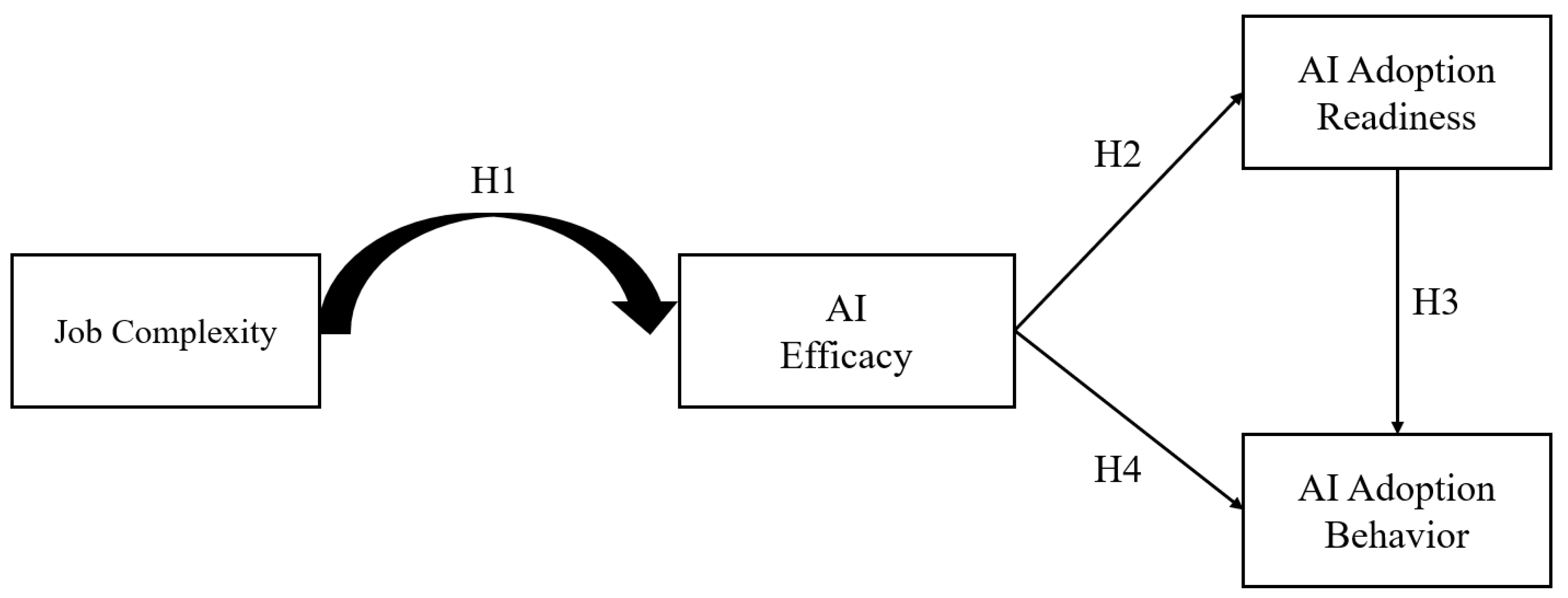

Mollick, 2024). We extend this framework by theorizing that job complexity determines the opportunity for task–technology alignment, which is defined as GenAI’s bounded capabilities match the demands of the job. At moderate levels of complexity, this alignment facilitates frequent, successful human–AI interactions that strengthen self-efficacy and readiness for adoption. At the extremes, misfit either limits meaningful engagement or generates repeated failure experiences, undermining confidence. This reasoning suggests that job complexity exerts an inverted-U-shaped effect on AI self-efficacy, which in turn promotes readiness and actual adoption behavior. We present our proposed model in

Figure 1.

To test these propositions, we conducted two empirical studies (N1 = 306, N2 = 246) in a private higher education institution in the United States, representing a context that naturally varies in job complexity and exposure to AI technologies. The multi-study design enables robust examination of the hypothesized curvilinear relationships and the mediating role of AI self-efficacy in shaping adoption outcomes.

This research advances theory and practice in three primary ways. Collectively, these contributions respond to both the empirical puzzle of uneven and inconsistent GenAI effects across jobs and the theoretical gap in how existing task–technology fit perspectives account for these patterns. First, it extends TTF theory by demonstrating that fit is not uniformly beneficial but follows a nonlinear pattern. We identify a “paradox of fit,” where both very low and very high job complexity undermine employees’ confidence in using AI. We also discover the inverted-U relationship that defines a “sweet spot” where task demands and AI capabilities align to foster self-efficacy. Second, the study advances the psychology of technology adoption by introducing AI self-efficacy and AI adoption readiness as key mechanisms. Rather than treating adoption as a simple outcome of intention, we show that AI adoption readiness, the active cognitive and emotional preparation to use AI, translates confidence into action. This highlights that successful adoption depends as much on psychological readiness as on technical fit. Third, the research integrates job design and technology adoption perspectives to explain how the structure of work shapes AI use. Job complexity determines whether employees encounter opportunities that build or erode confidence, positioning AI adoption as both a technical and developmental process. Practically, these findings emphasize that a one-size-fits-all approach to AI deployment is ineffective. Organizations should tailor implementation to job complexity, maintain human involvement in simpler roles, and manage expectations in more complex ones, fostering the moderate “Goldilocks zone” where human–AI collaboration is most productive.

2. Theory and Hypothesis

We turn to the Task Technology Fit (TTF) framework as our theoretical foundation to understand how generative AI adoption plays out. TTF theory rests on the premise that technology has a positive effect on utilization and performance when it fits with task requirements (

Chung et al., 2015;

Goodhue & Thompson, 1995). The antecedents of TTF include task characteristics, such as task complexity and interdependence (

Campbell, 1988;

Wood, 1986), and technology characteristics, such as processing speed, accuracy, and usability (

Goodhue & Thompson, 1995;

Zigurs & Buckland, 1998). At its core, this framework holds fit as the key to technology utilization by shaping employees’ beliefs about the technology’s usefulness and value for accomplishing their tasks. These beliefs, in turn, affect adoption decisions and ultimately impact performance (

Goodhue & Thompson, 1995). In this study, we focus on the adoption pathway, examining how this alignment influences employees’ AI adoption behavior. However, applying this framework to generative AI requires careful consideration of the technology’s unique characteristics and constraints.

This consideration is particularly urgent given that empirical findings regarding the influence of job complexity on technology adoption remain inconsistent, creating mixed findings. One stream of research posits a positive linear relationship driven by rational utility, arguing that high task complexity drives the necessity for technological tools. For instance,

Awa et al. (

2017) suggest that employees in complex roles are more likely to adopt systems to facilitate progression, while

Q. Zhang et al. (

2025) argue that high complexity can act as a “challenge appraisal,” framing AI as a necessary resource that boosts self-efficacy. Conversely, a second stream suggests a negative relationship, identifying complexity as a barrier rather than a driver.

Malik et al. (

2022), for example, identify “techno-complexity” as a primary source of stress, arguing that when tasks are already demanding, the introduction of tools that also comes with its own complexity creates “technostress” and feelings of incompetence. This aligns with findings in healthcare contexts where high job complexity weakens the positive impact of AI because current technologies lack the reliability to handle nuanced, high-stakes ambiguity, leading to a capability mismatch (

Huo et al., 2025).

Recent scholarship has attempted to resolve these contradictory findings by suggesting the relationship is curvilinear. Notably,

X. Zhang et al. (

2025) provide empirical evidence of an inverted U-shaped relationship in digital performance. However, their framework focuses on enterprise social media (ESM), attributing the decline at high complexity to “information overload” and social distraction. We argue that the mechanisms governing Generative AI differ fundamentally from social media. Unlike ESM, where the friction is caused by excessive input (noise), the friction in high-complexity GenAI use is caused by insufficient capability (failure). Because Generative AI possesses specific bounded capabilities, the barrier at high complexity is not that the user is overwhelmed by information, but that the AI fails to perform the necessary reasoning, leading to “enactive failure” that erodes confidence (

Bandura, 2000). Thus, while we build on the curvilinear premise, we diverge from prior work by identifying AI Self-Efficacy, developed through successful mastery experiences, as the distinct psychological mechanism that explains why adoption falters at the extremes of both automation (low complexity) and capability failure (high complexity).

More specifically, applying TTF logic to generative AI (GenAI) requires recognizing that GenAI possesses bounded capabilities. GenAI excels at pattern recognition and information processing but struggles with contextual interpretation, tacit knowledge synthesis, or reasoning capabilities (

Brynjolfsson et al., 2025;

Jarrahi, 2018). These bounded capabilities fundamentally shape how employees interact with GenAI. When task demands align with AI’s capabilities, jobs tend to create frequent opportunities for productive human-AI collaboration that build confidence through repeated use, whereas when task demands exceed or fall short of AI’s boundaries, jobs typically provide limited meaningful opportunities for integration, constraining confidence development. This misfit between GenAI and the employee’s task is bidirectional. GenAI can misfit the user’s needs by performing the task inadequately, or it can misfit the user and task demands by exceeding the user’s needs, leading to minimal interaction with AI. We therefore extend TTF by examining how job complexity shapes interaction opportunity, the task-afforded occasions for human-AI collaboration. By aligning task demands with AI’s bounded capabilities, job complexity influences the accumulation of mastery experiences that build self-efficacy, subsequently affecting adoption decisions. In the following sections, we delineate this mechanism in detail and present the key concepts and constructs in

Table 1.

2.1. From Task-Technology Fit to AI Self-Efficacy

TTF theory maintains that task-technology fit drives utilization through employees’ beliefs about technology usefulness and value (

Goodhue & Thompson, 1995). We extend this framework by examining how fit shapes AI self-efficacy, that is, employees’ beliefs in their capability to successfully use AI to accomplish their work tasks (

Compeau & Higgins, 1995). This construct differs from perceived usefulness by focusing not on whether AI is helpful, but on whether employees believe they can successfully benefit that help.

Prior technology adoption research has extensively examined self-efficacy and computer self-efficacy as a broad belief about one’s ability to use information technologies or computing systems (

Compeau & Higgins, 1995;

Venkatesh et al., 2003). We suggest that generative AI’s probabilistic and interactive nature may require a more nuanced conceptualization of efficacy. Recent work by

Wang and Chuang (

2024) demonstrates that AI self-efficacy captures AI-specific characteristics that traditional technology self-efficacy scales neglect, suggesting that the construct warrants distinct theoretical and empirical treatment. Unlike traditional systems that produce relatively predictable outputs through fixed interfaces, generative AI appears to engage users in iterative dialogue where outputs can vary in quality and accuracy, potentially requiring continuous judgment about when to trust, refine, or override algorithmic suggestions (

Agrawal et al., 2019;

Dell’Acqua et al., 2023;

Jarrahi, 2018). Additionally, GenAI’s capabilities tend to be context-dependent and bounded, performing well at some tasks while struggling with others, which may demand that users develop discernment about when AI augments versus hinders their work. Accordingly, we conceptualize AI self-efficacy as capturing employees’ confidence in navigating these distinctive challenges. Their belief that they can effectively integrate generative AI into core work tasks through skillful prompting, critical evaluation, and sound judgment about its appropriate application. This domain-specific construct extends beyond operating AI tools to encompass the capability for productive human-AI collaboration.

We propose that job complexity, which encompasses the cognitive demands, task variety, and problem-solving requirements of work (

Shalley et al., 2009;

Wood, 1986), has an inverted-U relationship with AI self-efficacy. This curvilinear effect emerges through mastery experiences, which is often considered as the primary source of self-efficacy development (

Bandura, 1997;

Usher & Pajares, 2008). When job complexity aligns with AI’s bounded capabilities, employees accumulate positive interactions that build confidence. When it misaligns, either too low or too high, interaction opportunities diminish.

The Paradox of Fit: When High Technical Alignment Undermines Adoption

We define the paradox of fit as a non-monotonic pattern in which task–technology alignment that appears favorable can, under specific conditions, suppress AI self-efficacy and subsequent adoption behavior. This departs from traditional Task–Technology Fit logic, which typically assumes that closer alignment reliably improves evaluations and use (

Goodhue & Thompson, 1995). In GenAI, whose value depends on iterative, human-in-the-loop interaction and mastery experiences, both “over-fit” (tasks too simple relative to capabilities) and “under-fit” (tasks exceeding capabilities) can erode confidence rather than build it (

Bandura, 2000). In the following sections, we unpack how and why this pattern of relationship might emerges across varying levels of job complexity and demonstrate its implications for effective human–AI collaboration.

Table 2 provides a summary of the hypotheses and their corresponding theoretical rationales.

2.2. The Curvilinear Effect of Job Complexity on AI Self-Efficacy

2.2.1. Low Job Complexity: The Automation Paradox

At low job complexity, roles involve routine, rule-based tasks with clear procedures and predictable patterns, such as data entry, appointment scheduling, or basic document formatting. Generative AI’s capabilities substantially exceed these task demands, enabling near-complete automation with minimal human engagement (

Huang & Rust, 2018). This creates a paradox that challenges TTF predictions. While AI fits these tasks technically, automation eliminates the human-AI interactions necessary for self-efficacy development. Without ongoing interaction opportunities, employees cannot accumulate the mastery experiences that build confidence. Consider an administrative assistant whose scheduling is handled by Gen AI. After configuring initial preferences and rules, they rarely engage with the system as it autonomously manages appointments, sends reminders, and resolves conflicts. Such employees have few opportunities to develop and demonstrate their capability to leverage Gen AI effectively. Thus, despite high technical fit, AI self-efficacy might remain underdeveloped at low job complexity. This represents a situation where this high degree of fit, driven by GenAI’s excessive capacity, inadvertently worsens human-AI collaboration opportunities.

2.2.2. Moderate Job Complexity: The Augmentation Sweet Spot

At moderate job complexity, roles, such as market analysis, report synthesis, and strategic recommendations, require judgment and contextual understanding that prevent full automation (

Marler, 2024;

Raisch & Krakowski, 2021). These requirements create the optimal conditions for human-AI collaboration. Generative AI handles information processing and routine analysis while humans provide quality assessment, ethical considerations, and expert reasoning, establishing a “human-in-the-loop” dynamic with frequent interaction opportunities (

Jarrahi, 2018). Such interactions constitute guided mastery experiences where AI scaffolds performance while employees retain decision-making control. These are the ideal conditions for self-efficacy development (

Bandura, 1997). Consider how a market analyst uses AI to process survey data and identify patterns while applying human judgment to interpret strategic implications. Each task requires interdependent collaboration that reinforces the employee’s capability. This continuous stream of successful interactions enables employees to build evidence of their ability to leverage AI effectively and thus contribute their belief in their confidence building (

Dell’Acqua et al., 2023). Unlike the automation paradox at low complexity, moderate complexity maximizes self-efficacy development through sustained, meaningful human-AI collaboration opportunities.

2.2.3. High Job Complexity: The Capability Ceiling

At high job complexity, roles involve strategic decisions, stakeholder negotiations, and policy development that demand tacit knowledge, political navigation, and judgment based on years of institutional expertise (

Shalley et al., 2009;

Simon, 1991). These core requirements exceed generative AI’s current capabilities in contextual interpretation and nuanced reasoning, creating a fundamental task-technology misfit (

Goodhue & Thompson, 1995). This misfit becomes evident in practice. Consider a hospital executive developing strategic responses to new regulatory changes. She inputs institutional context, past policies, and stakeholder concerns, expecting nuanced recommendations. Instead, AI generates generic strategies that overlook organizational constraints, misread political dynamics, and ignore the institutional knowledge essential for implementation (

Lebovitz et al., 2021). After attempts yield similar failures, employees in high-complexity roles might accurately assess that AI cannot handle their core strategic work yet. These negative mastery experiences reduce employees’ willingness to interact with and explore AI’s capabilities, creating a self-reinforcing cycle where limited interaction hinders the learning and navigation needed to develop further confidence in using AI (

Venkatesh, 2000). Thus, at high complexity, evidence-based assessment of poor task-technology fit leads to diminished self-efficacy. Taken together, we hypothesized that:

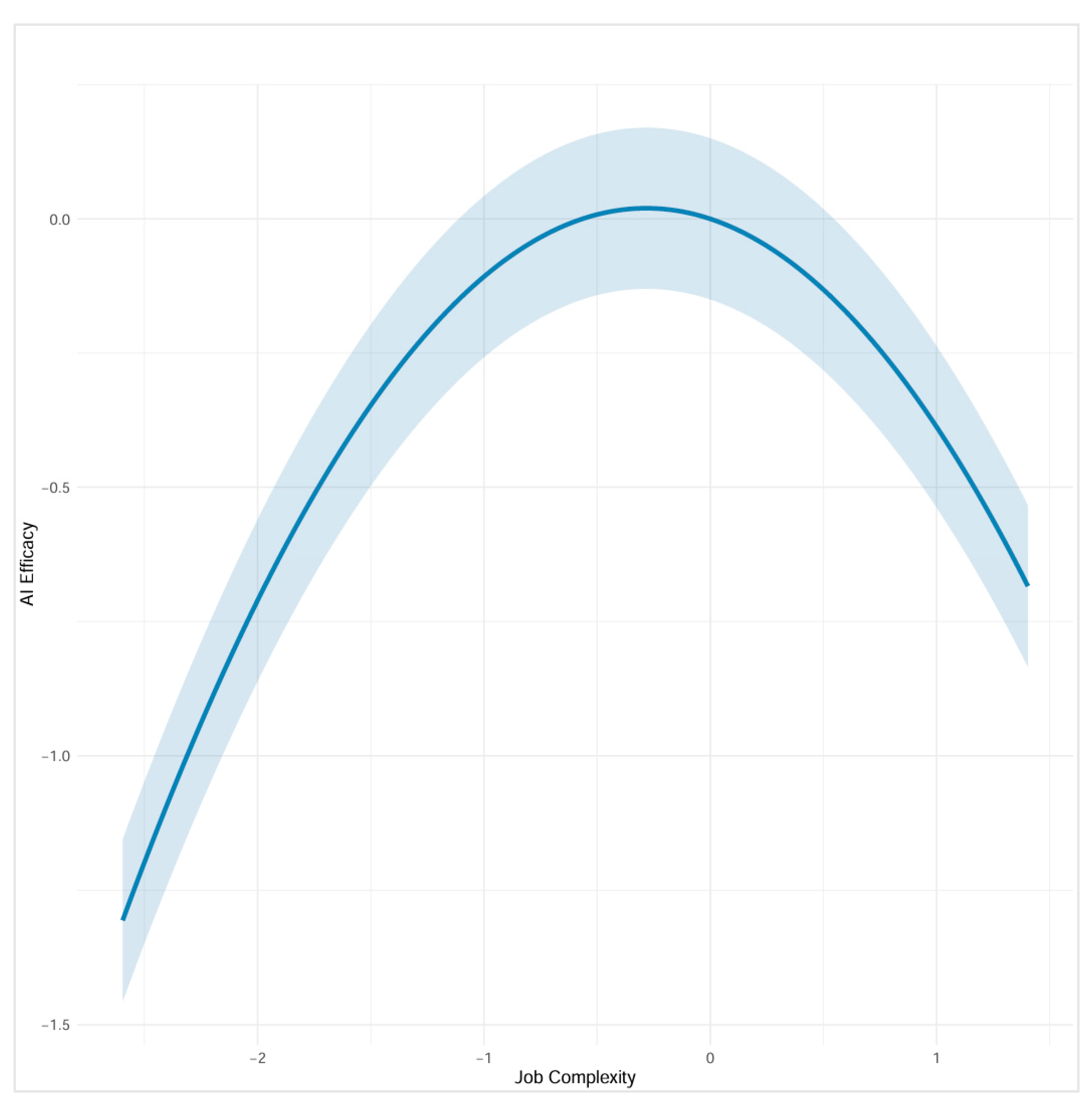

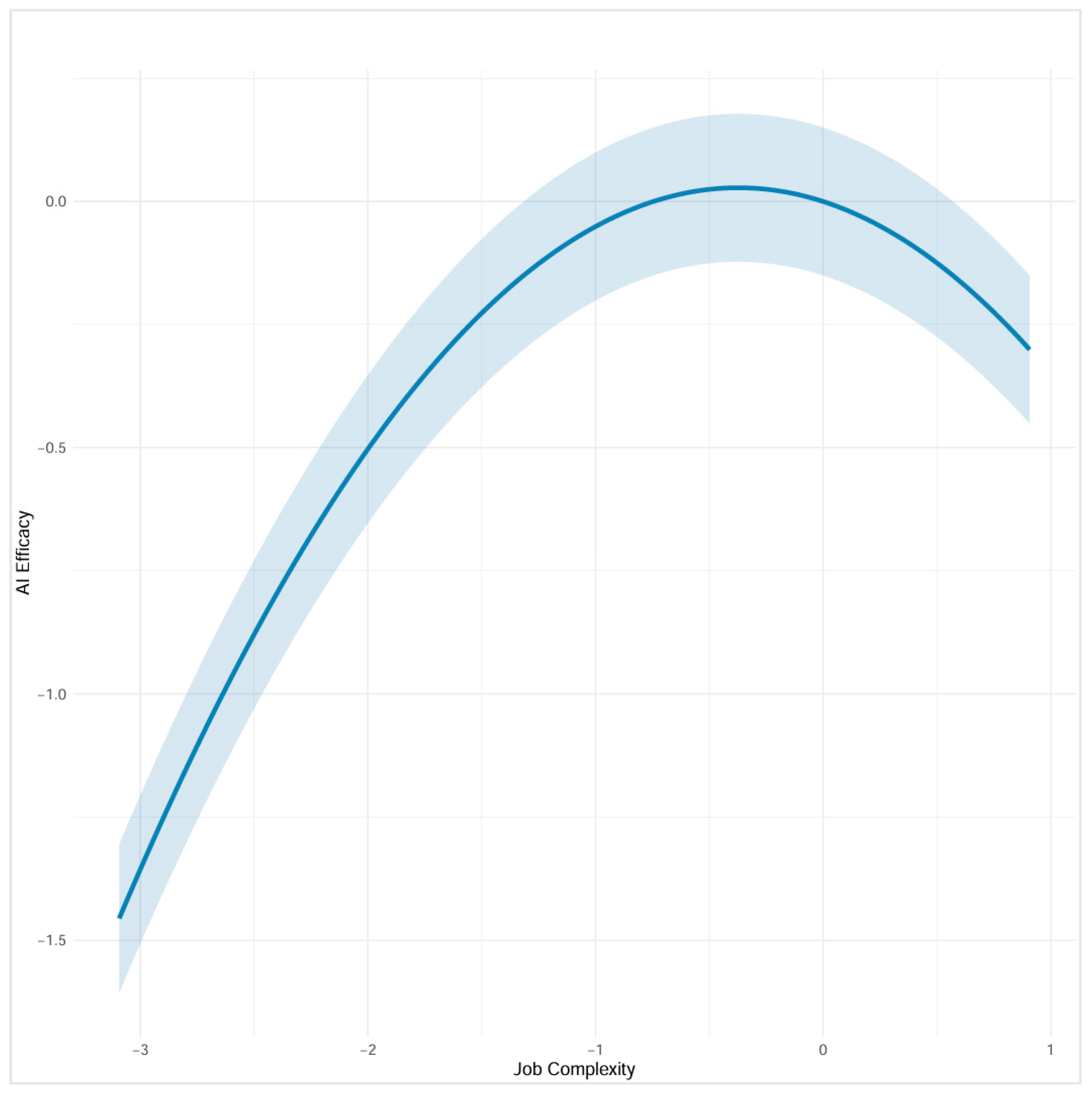

H1. Job complexity has an inverted-U shaped relationship with AI self-efficacy, such that AI self-efficacy initially increases as job complexity moves from low to moderate levels but decreases as job complexity increases beyond moderate levels to high complexity.

2.3. AI Self-Efficacy and Adoption Readiness

We propose that AI self-efficacy positively influences AI adoption readiness, the extent to which individuals prepare to integrate AI beyond minimal task requirements (

Armenakis et al., 1993;

Blut & Wang, 2020;

Rafferty et al., 2013). This readiness represents a multi-dimensional construct encompassing cognitive understanding of AI’s capabilities and boundaries, affective orientation toward AI integration, and forming concrete implementation intentions (

Armenakis et al., 1993;

Rafferty et al., 2013). Developing these dimensions requires allocating limited cognitive and emotional resources, with self-efficacy influencing whether employees make this investment (

Bandura, 1997). More specifically, employees with high self-efficacy, having accumulated positive mastery experiences, allocate resources across all three dimensions. They invest in learning AI’s capabilities and experimenting with applications (cognitive), develop positive orientations toward integration (affective), and form concrete implementation plans (intentional). This allocation pattern reflects self-efficacy’s motivational function. Individuals with high self-efficacy expect returns from preparation efforts and thus invest in skill development (

Bandura, 1997;

Colquitt et al., 2000). Preparation proves especially critical for generative AI because successful adoption requires understanding the technology’s boundaries and developing judgment capabilities for output evaluation. These capabilities emerge through deliberate practice rather than intuitive use. In line with this reasoning, empirical evidence also supports this pathway in both technology adoption (

Parasuraman, 2000) and organizational change contexts (

Cunningham et al., 2002). Thus, we hypothesize that:

H2. AI self-efficacy is positively related to AI adoption readiness.

2.4. AI Adoption Readiness and AI Adoption Behavior

We propose that AI adoption readiness positively influences AI adoption behavior, which we define as the frequency and extent of actual AI use in daily work. Self-efficacy captures capability beliefs developed through mastery experiences, while readiness captures preparedness built through deliberate skill investment (

Armenakis et al., 1993). This distinction matters because capability beliefs require practical implementation skills to translate into action (

Ajzen, 1991;

Venkatesh et al., 2003). Technology adoption research documented that facilitating conditions such as skills, knowledge, and practical understanding influence whether positive beliefs translate into usage (

Venkatesh et al., 2003). We argue that readiness provides these facilitating conditions by equipping employees with procedural and practical knowledge for AI integration. Those who invest in readiness develop practical knowledge of when and how AI aligns with task demands and act decisively, while those without such preparation hesitate the act and adopt the new technology in daily uses (

Venkatesh et al., 2003). Research on organizational change consistently shows that readiness, not merely positive attitudes, strongly predict whether employees successfully adopt new technologies (

Holt et al., 2007;

Weiner, 2009). Even motivated employees struggle to translate intentions into action without the concrete skills, practical knowledge that readiness provides (

Taylor & Todd, 1995;

Venkatesh et al., 2003). Thus, we hypothesize that

H3. AI adoption readiness is positively related to AI adoption behavior.

2.5. AI Self-Efficacy as a Direct Driver of AI Adoption

We argue that AI self-efficacy directly influences AI adoption behavior beyond its indirect effect through readiness. This direct path matters because generative AI’s context-dependent and probabilistic nature requires iterative refinement (

Knoth et al., 2024). Outputs vary with each use, demanding persistence through trial-and-error (

Agrawal et al., 2019). Self-efficacy shapes willingness to voluntarily expand AI use beyond requirements and influences persistence through these inevitable variations (

Bandura, 1997). When encountering unhelpful AI outputs, employees with low self-efficacy interpret failures as confirmation of unsuitability and abandon use, while those with high self-efficacy view failures as surmountable challenges and persist through iteration (

Han et al., 2025). Self-efficacy operates independently of readiness. Even employees with practical capabilities need confidence to persist through such challenges rather than abandoning attempts prematurely (

Ajzen, 1991;

Marakas et al., 1998). Empirical evidence confirms this direct path. self-efficacy predicts technology persistence and continued usage beyond initial adoption, determines acceptance or rejection of AI-generated suggestions, and consistently influences adoption behavior across information systems contexts (

Compeau & Higgins, 1995;

Dietvorst et al., 2015;

Hong et al., 2002;

Venkatesh et al., 2003). Thus, we hypothesize that:

H4. AI self-efficacy is positively related to AI adoption behavior.

4. Discussion

In this research, we have proposed and found support for a non-linear relationship between job complexity and AI adoption. Our psychological pathway model offers a critical extension to Task-Technology Fit (TTF) theory, revealing why and how employees’ psychological responses to generative AI are shaped by their work structure. We found a “paradox of fit” that manifests as an inverted-U relationship. At low job complexity, we documented that high technical fit paradoxically undermines the human-AI interactions necessary for AI self-efficacy development, while at high job complexity, a clear capability misfit also undermines its utility. These findings make distinct contributions to our understanding of Task-Technology Fit, the formation of self-efficacy in human-AI collaboration, and the nature of technology adoption pathways, which we elaborate on below.

4.1. Theoretical Implications

Our findings offer a contribution to Task-Technology Fit (TTF) theory, particularly in its application to generative AI. In much of the technology adoption literature, “fit” is cast as a simple, linear good, where a better technical match invariably leads to more positive outcomes like adoption and performance. Our findings challenge this linear fit assumption, suggesting instead that “fit” can be a non-linear, inverted-U relationship. While the negative effect of excessive job complexity is clear, the positive slope from low to moderate complexity is modest in magnitude. We cautiously interpret this pattern, emphasizing its theoretical coherence and moderate practical significance over its statistical strength. Our empirical results are consistent with conceptual work on human-AI collaboration, which has long argued for an optimal “augmentation” partnership, distinct from full automation on one side and capability failure on the other. Our research adds critical and empirical nuance to this idea and extends it in two crucial ways. First, we provide replicated evidence for this non-linear curve at different times and by using different measures of job complexity. Second, and more importantly, we extend this reasoning by identifying the psychological mechanism, which is AI self-efficacy developed through interaction opportunities, that explains why this “Goldilocks zone” of augmentation is so critical for adoption and development of AI self-efficacy, where individuals feel confident in using AI in their task, thus leading to daily use and much greater adoption later on through their interactions.

Our research also reveals a surprising paradox for organizations and their most high-complexity roles. Scholars have suggested that the greatest strategic value of generative AI lies in its ability to augment these critical, non-routine roles where job complexity may be high (

Qian & Xie, 2025). This is precisely where human-AI collaboration is seen as most vital for innovation and strategic decision-making. We found that their AI self-efficacy significantly declines under these very circumstances, as employees in high-complexity jobs might not have opportunity to engage AI for their core strategic tasks. This evidence suggests that these employees pay a high price for their attempts at augmentation. They experience enactive failure as the AI’s current capabilities are exceeded, leading to frustration, tool abandonment, and the erosion of their confidence in the technology. These findings both challenge and qualify the overly simplistic proposition that generative AI is a universal augmentation tool. Rather, our findings indicate that without careful task alignment, attempts at high-level augmentation can backfire, eroding the very confidence organizations hope to build in their most critical employees.

Finally, our research offers a novel contribution to the technology adoption literature. Although organizational scholars have devoted a great deal of attention to the role of behavioral intentions in driving technology use, they have largely neglected the deeper, more active psychological state of adoption readiness. The limited body of research on this topic has yielded mixed, inconsistent results, with scholars frequently noting a persistent “intention-behavior gap” where positive intentions fail to translate into actual use (

Jeyaraj et al., 2023). Our research takes a step toward adding new insights by introducing AI Adoption Readiness as a critical intervening variable. We show that for complex and interactive technologies like generative AI, a simple “intention to use” is insufficient. Our findings suggest that “readiness”, a richer construct capturing active cognitive and affective preparation, is the true psychological bridge that translates belief (efficacy) into action (use). These findings suggest that to truly understand when and how positive beliefs shape behavior, researchers need to consider the pivotal role of psychological readiness, rather than relying solely on the more tenuous measure of behavioral intention.

4.2. Practical Implications

Our findings offer clear practical guidance for leaders and managers navigating the implementation of generative AI. The observed inverted-U relationship, though moderate in effect size, suggests that a one-size-fits-all deployment strategy is unlikely to succeed. The design of the job itself remains a critical determinant of AI adoption outcomes, and organizations should interpret these effects as indicative rather than definitive. For instance, in low-complexity roles, managers must be wary of the automation paradox. While it may be efficient to fully automate routine tasks, our findings imply this robs employees of the very interaction opportunities needed to build AI self-efficacy. A more prudent strategy would involve redesigning these roles to maintain a human-in-the-loop, thereby building the confidence necessary for future, more advanced AI adoption. Conversely, in high-complexity roles, our results suggest managers must proactively manage expectations to avoid the capability ceiling. Deploying AI as a supposed strategic partner in these roles may lead to repeated enactive failure experiences that erode efficacy and build resistance. Instead, AI should be framed as a specialized assistant for discrete, well-defined sub-tasks, such as information synthesis or drafting initial communications, rather than a solution for core strategic problems. This approach properly identifies moderately complex roles as the sweet spot for augmentation, where human-AI collaboration can be most productively fostered. These insights directly address the inconsistency in prior research noted in the introduction, where empirical findings on AI adoption varied widely across occupations and levels of job complexity.

Our results also carry significant implications for employee and organizational development, which address the research gap identified in the introduction regarding the limited understanding of psychological mechanisms in AI adoption. Our psychological pathway model reveals that AI adoption is not just a technical problem, but also one of psychological development. For organizations and HR leaders, this means training must evolve beyond teaching technical skills. Our findings indicate that AI Adoption Readiness is a critical bridge between confidence and use. Therefore, training interventions must be explicitly designed to build judgment. This includes teaching employees when to use AI, how to critically evaluate its probabilistic outputs, and what its true limitations are. For employees, our model highlights that AI self-efficacy is the engine that drives this entire process. Rather than waiting for formal training, employees can take an active role by proactively seeking out guided mastery experiences, which are small, achievable, confidence boosting wins with AI. Using the tool for a discrete sub-task they know it can handle provides the initial, successful interaction that is the necessary fuel for the harder work of building deep readiness.

4.3. Limitations and Future Directions

The contributions of this research should be contextualized within a few key boundaries, which in turn highlight promising avenues for future inquiry. First, our study’s cross-sectional design limits our ability to make definitive causal inferences about the psychological pathway we proposed. It is certainly possible that the relationships are reciprocal. For example, AI self-efficacy may not only lead to AI use, but successful use may also build efficacy, creating a positive reinforcement loop. On the other hand, it is also possible that employees high in readiness are the ones who proactively seek out the very AI interactions that build their self-efficacy in the first place. The cross-sectional design may also limit our ability to confirm the curvilinear nature of the job complexity–AI self-efficacy relationship. Future longitudinal or experimental research could better determine whether changes in job complexity over time predict corresponding non-linear changes in AI self-efficacy, strengthening evidence for the proposed inverted-U pattern. While longitudinal models are a critical next step, establishing the fundamental associative structure of this pathway is a necessary and non-trivial first step. Our research is the first to provide robust, replicated evidence that this specific non-linear relationship exists and is associated with this psychological mechanism. Without this preliminary cross-sectional evidence, any causal investigation would be premature. Nevertheless, future research should build directly on our findings by using longitudinal, cross-lagged panel designs to untangle this co-evolutionary relationship between efficacy, readiness, and use over time.

Our findings also point to several more technical limitations that offer a clear agenda for future work. The study’s single-institution context constrains generalizability, and the O*NET-based job complexity measure in Study 1 provides only a simplified representation of work structure. While this setting allowed us to test our model within a consistent organizational culture and resource environment, it also represents a boundary condition. Faculty and staff in higher education face unique job demands, levels of autonomy, and institutional pressures regarding technology adoption that may differ significantly from those in corporate, government, or non-profit sectors. The inverted-U relationship we observed might shift or change shape in environments with different cultural norms, resource constraints, or performance incentives. Therefore, the proposed “paradox of fit” may not manifest uniformly across all contexts. For example, organizations mandate collaborative AI workflows with user training programs may experience limited curvilinear effects. Identifying such boundary conditions will clarify when and why the paradox of fit emerges, or fails to appear. Future research should therefore seek to replicate these findings across diverse industries and organizational contexts to establish the broader generalizability of our psychological pathway model. Furthermore, our dependent variable, AI adoption, was measured as frequency. This measure, however, is a crude proxy for a complex behavior. It is possible that the pathway we identified predicts frequent use, but not necessarily effective or appropriate use. For example, the quality of interactions, the amount of time spent, and adoption across different domains and use cases might be possible investigation areas. Additionally, AI adoption readiness and behavioral intention share conceptual proximity. Future research could empirically differentiate them using longitudinal or experimental designs. Finally, our model theorizes the specific psychological mechanisms linking job complexity to self-efficacy, such as enactive failures at the high end, but we did not directly measure these mediating processes. Future research might also want to investigate the exact mechanism that we describe, such as how mastery experiences are gained at different job levels and how this process directly mediates the relationship between job structure and self-efficacy.