Self-Compassion Components and Emotional Regulation Strategies as Predictors of Psychological Distress and Well-Being

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Self-Compassion Components, Psychological Distress and Well-Being

1.2. Emotion Regulation as a Mediator of the Relationship of Self-Compassion with Psychological Distress and Well-Being

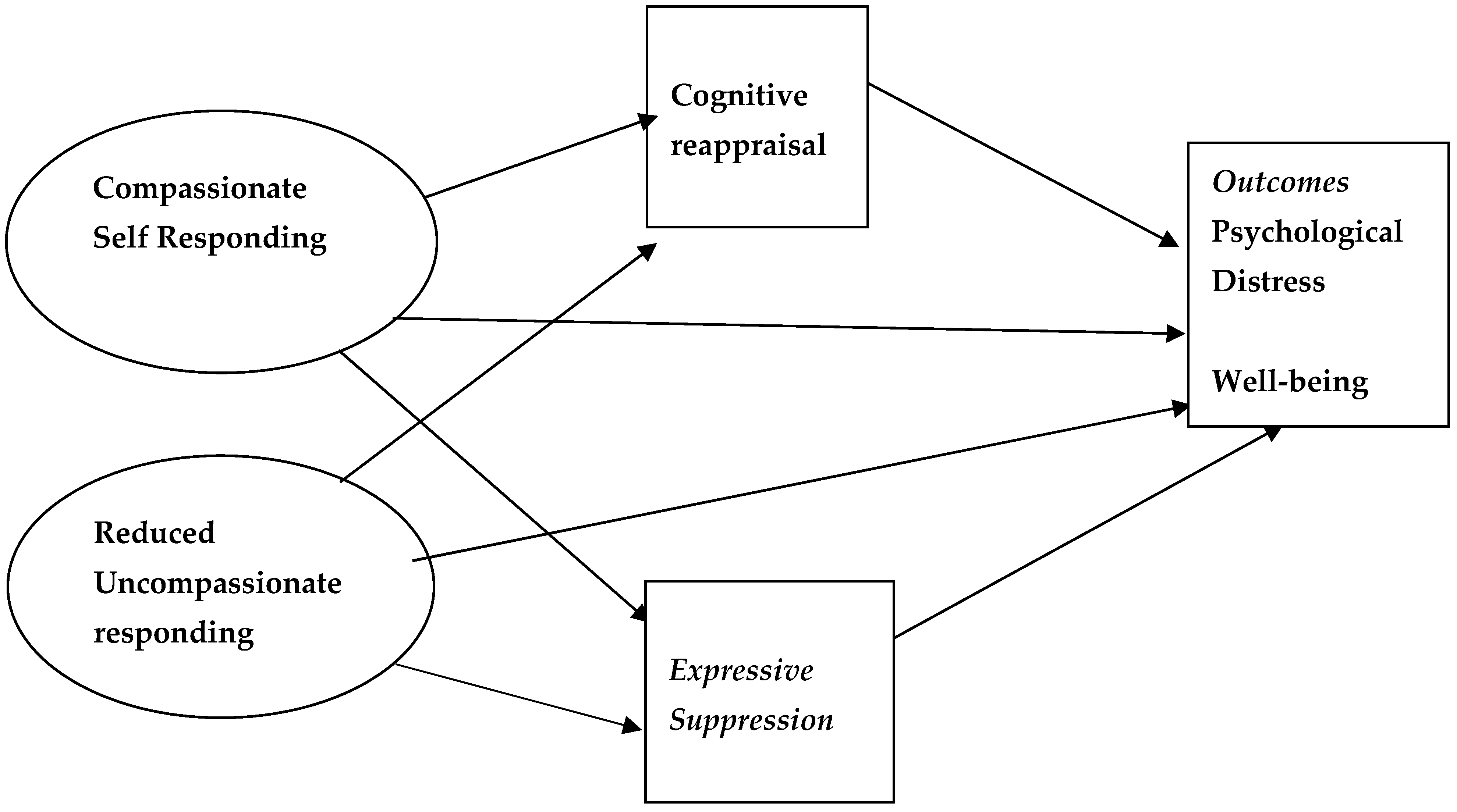

1.3. The Current Study

2. Method

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Measures

2.3. Measures of Psychological Distress

2.4. Measures of Well-Being

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Data Screening

3.2. Correlations Among the Measures

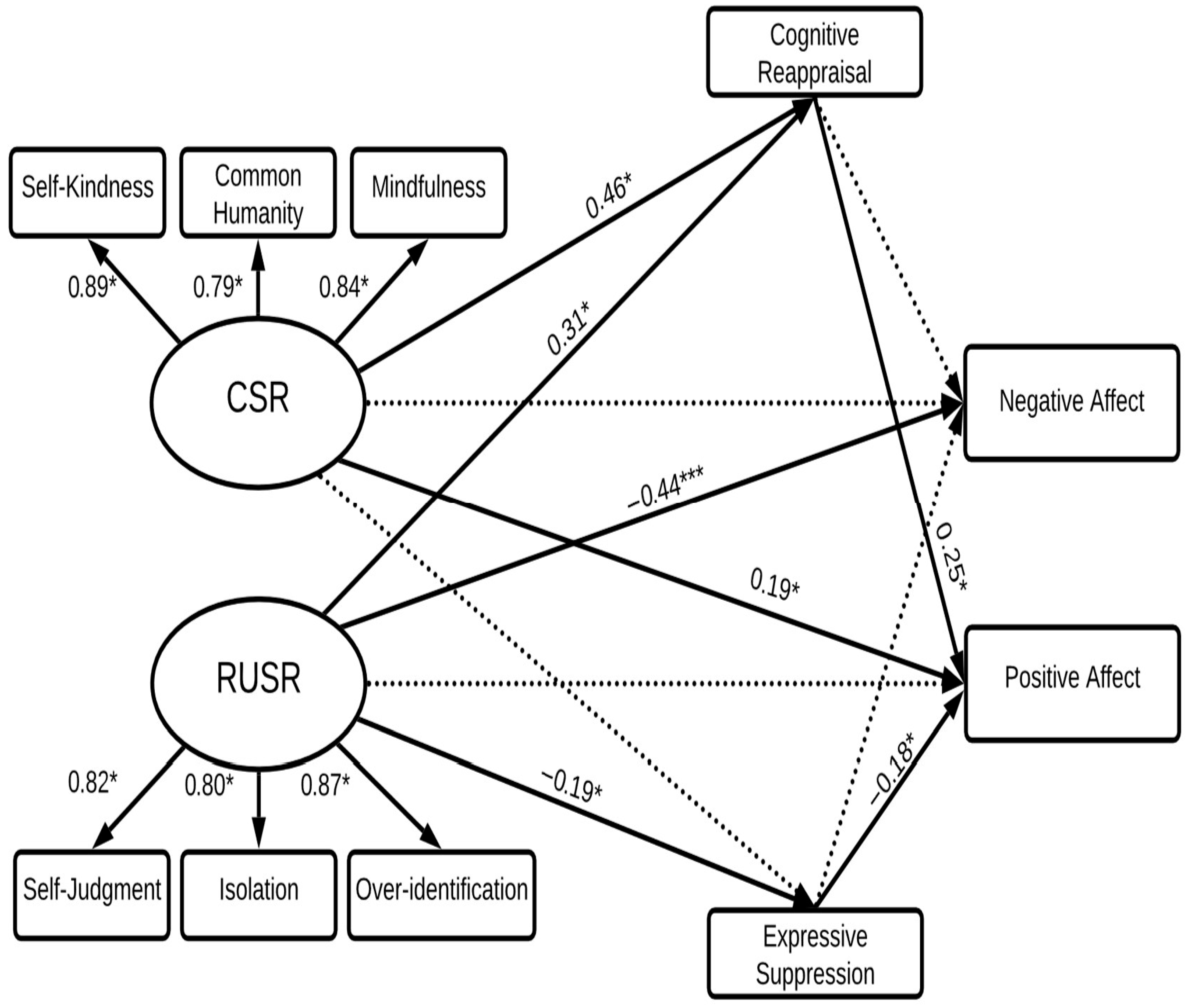

3.3. Prediction of Negative Affect and Positive Affect

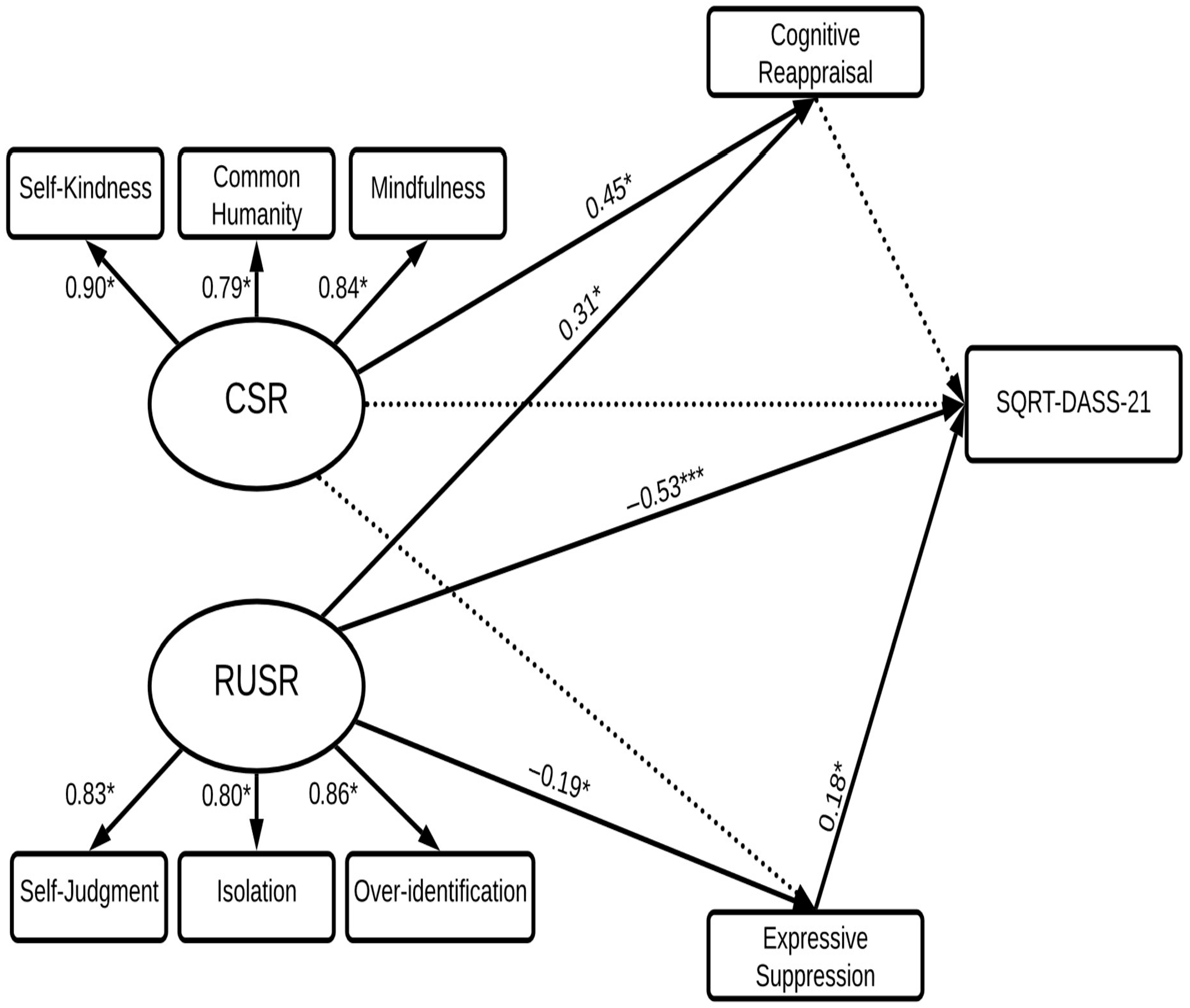

3.4. Prediction of Psychological Distress

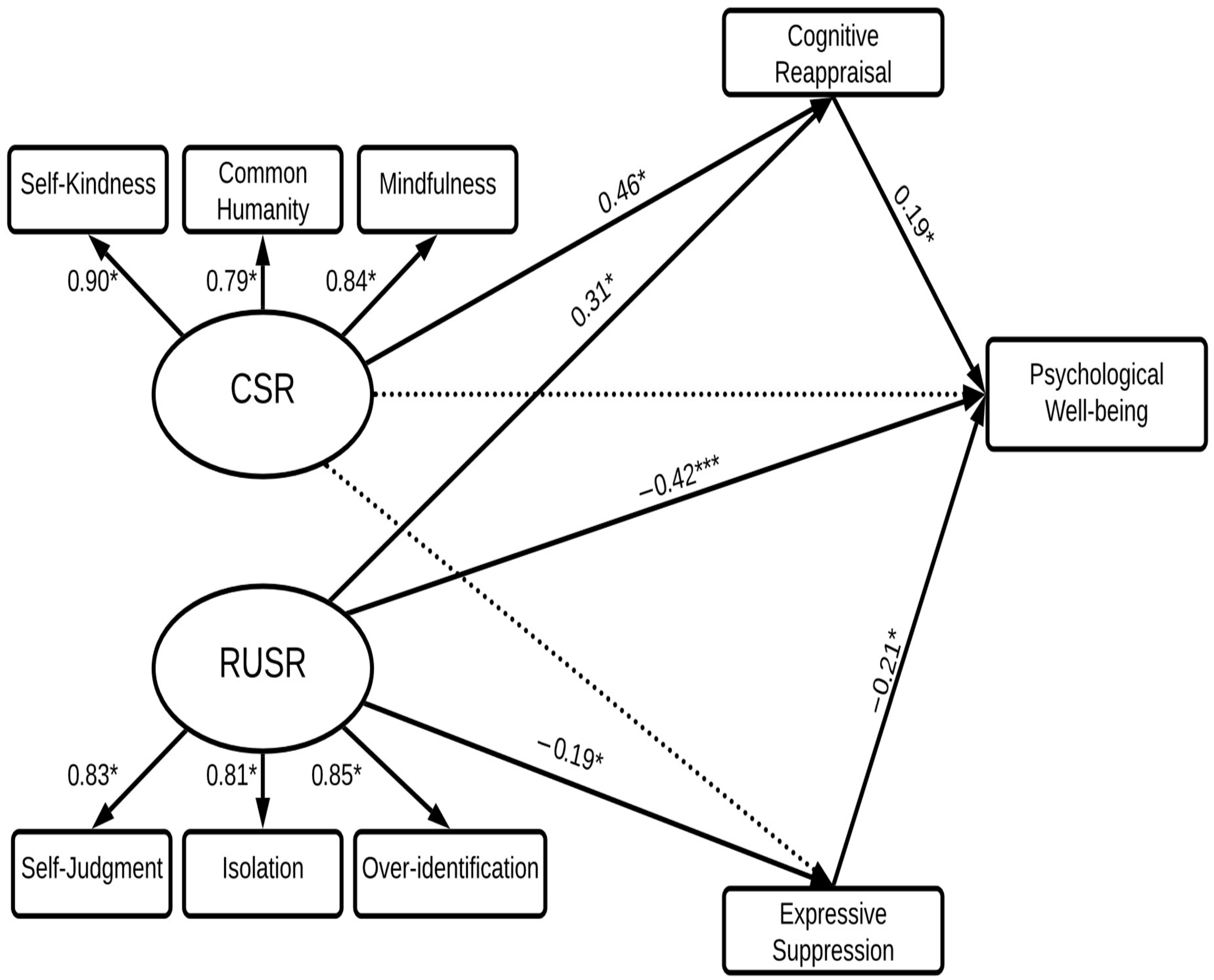

3.5. Prediction of Psychological Well-Being (Eudaimonic Well-Being)

3.6. Results of SEM for Subjective Well-Being

4. Discussion

4.1. Psychological Distress Findings

4.2. Findings for Hedonic and Eudaimonic Well-Being

4.3. Clinical Implications, Methodological Considerations, and Directions for Future Research

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders-Text revision (DSM-5-TR). American Psychiatric Association Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bates, G. W., Elphinstone, B., & Whitehead, R. (2021). Self-compassion and emotional regulation as predictors of social anxiety. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 94(3), 426–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauer, J. J., McAdams, D. P., & Pals, J. L. (2008). Narrative identity and eudaimonic well-being. Journal of Happiness Studies, 9(1), 81–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berking, M., & Whitley, B. (2014). Emotion regulation: Definition and relevance for mental health. In Affect regulation training (pp. 5–17). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Chio, F. H., Mak, W. W., & Ben, C. L. (2021). Meta-analytic review on the differential effects of self-compassion components on well-being and psychological distress: The moderating role of dialecticism on self-compassion. Clinical Psychology Review, 85, 101986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crawford, J. R., & Henry, J. D. (2004). The Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS): Construct validity, measurement properties and normative data in a large non-clinical sample. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 43(3), 245–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutajar, K., & Bates, G. W. (2025). Australian women in the perinatal period during COVID-19: The influence of self-compassion and emotional regulation on anxiety, depression, and social anxiety. Healthcare, 13, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diedrich, A., Hofmann, S. G., Cuijpers, P., & Berking, M. (2016). Self-compassion enhances the efficacy of explicit cognitive reappraisal as an emotion regulation strategy in individuals with major depressive disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 82, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E. (1984). Subjective well-being. Psychology Bulletin, 95(3), 542–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dryman, M. T., & Heimberg, R. G. (2018). Emotion regulation in social anxiety and depression: A systematic review of expressive suppression and cognitive reappraisal. Clinical Psychology Review, 65, 17–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finlay-Jones, A. L. (2017). The relevance of self-compassion as an intervention target in mood and anxiety disorders: A narrative review based on an emotion regulation framework. Clinical Psychologist, 21(2), 90–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, B. L. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. American Psychologist, 56(3), 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, P. (Ed.). (2005). Compassion: Conceptualisations, research and use in psychotherapy. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert, P., McEwan, K., Matos, M., & Rivis, A. (2011). Fears of compassion: Development of three self-report measures. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 84(3), 239–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouveia, V. V., Milfont, T. L., Da Fonseca, P. N., & de Miranda Coelho, J. A. P. (2009). Life satisfaction in Brazil: Testing the psychometric properties of the satisfaction with life scale (SWLS) in five Brazilian samples. Social Indicators Research, 90(2), 267–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, J. J. (2015). Emotion regulation: Current status and future prospects. Psychological Inquiry, 26(1), 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, J. J., & John, O. P. (2003). Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: Implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(2), 348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henry, J. D., & Crawford, J. R. (2005). The short-form version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS-21): Construct validity and normative data in a large non-clinical sample. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 44(2), 227–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hofmann, S. G. (2014). Interpersonal emotion regulation model of mood and anxiety disorders. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 38(5), 483–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hofmann, S. G., Carpenter, J. K., & Curtiss, J. (2016). Interpersonal emotion regulation questionnaire (IERQ): Scale development and psychometric characteristics. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 40(3), 341–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modelling, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inwood, E., & Ferrari, M. (2018). Mechanisms of Change in the Relationship between self-compassion, emotion regulation and mental health: A systematic review. Applied Psychology Health and Well Being, 10(2), 215–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kline, R. B. (2015). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (4th ed.). Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Lovibond, S. H., & Lovibond, P. F. (1995). Manual for the depression anxiety & stress scales (2nd ed.). Psychology Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- MacBeth, A., & Gumley, A. (2012). Exploring compassion: A meta-analysis of the association between self-compassion and psychopathology. Clinical Psychology Review, 32(6), 545–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marsh, H. W., Fraser, M. I., Rakhimov, A., Ciarrochi, J., & Guo, J. (2023). The bifactor structure of the self-compassion scale: Bayesian approaches to overcome exploratory structural equation modelling (ESEM) limitations. Psychological Assessment, 35(8), 674–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McBride, N. L., Bates, G. W., Elphinstone, B., & Whitehead, R. (2022). Self-compassion and social anxiety: The mediating effect of emotion regulation strategies and the influence of depressed mood. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 95(4), 1036–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muris, P., & Otgaar, H. (2020). The process of science: A critical evaluation of more than 15 years of research on self-compassion with the self-compassion scale. Mindfulness, 11, 1469–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muris, P., & Petrocchi, N. (2017). Protection or vulnerability? A meta-analysis of the relations between the positive and negative components of self-compassion and psychopathology. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 24(2), 373–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neff, K. D. (2003a). Self-compassion: An alternative conceptualization of a healthy attitude toward oneself. Self and Identity, 2(2), 85–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neff, K. D. (2003b). The development and validation of a scale to measure self-compassion. Self and Identity, 2(3), 223–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neff, K. D. (2016). The self-compassion scale is a valid and theoretically coherent measure of self-compassion. Mindfulness, 7(1), 264–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neff, K. D. (2020). Commentary on muris and otgaar (2020): Let the empirical evidence speak on the self-compassion scale. Mindfulness, 11(8), 1900–1909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neff, K. D. (2023). Self-compassion: Theory, method, research, and intervention. Annual Review of Psychology, 74(1), 193–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neff, K. D., Long, P., Knox, M. C., Davidson, O., Kuchar, A., Costigan, A., Williamson, Z., Rohleder, N., Tóth-Király, I., & Breines, J. G. (2018). The forest and the trees: Examining the association of self-compassion and its positive and negative components with psychological functioning. Self and Identity, 17(6), 627–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavot, W., & Diener, E. (2008). The satisfaction with life scale and the emerging construct of life satisfaction. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 3(2), 137–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C. D. (1989). Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57(6), 1069–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C. D., & Keyes, C. L. M. (1995). The structure of psychological well-being revisited. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69(4), 719–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vally, Z., & Ahmed, K. (2020). Emotion regulation strategies and psychological wellbeing: Examining cognitive reappraisal and expressive suppression in an Emirati college sample. Neurology, Psychiatry, and Brain Research, 38, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, D., Clark, L. A., & Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(6), 1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehead, R., & Bates, G. (2016). The transformational processing of peak and nadir experiences and their relationship to eudaimonic and hedonic well-being. Journal of Happiness Studies, 17(4), 1577–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zessin, U., Dickhäuser, O., & Garbade, S. (2015). The relationship between self-compassion and well-being: A meta-analysis. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being, 7(3), 340–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | M | SD | α | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. NA-PANAS | 25.26 | 8.50 | 0.88 | - | |||||||||

| 2. DASS-21 | 19.46 | 14.13 | 0.95 | 0.70 ** | - | ||||||||

| 3. PA-PANAS | 34.67 | 8.18 | 0.90 | −0.32 ** | −0.47 ** | - | |||||||

| 4. PWBS | 153.31 | 26.54 | 0.92 | −0.60 ** | −0.71 ** | 0.69 ** | - | ||||||

| 5. SWLS | 15.26 | 5.19 | 0.90 | −0.49 ** | −0.49 ** | 0.42 ** | 0.63 ** | - | |||||

| 6. CR-ERS | 28.00 | 7.50 | 0.90 | −0.43 ** | −0.46 ** | 0.45 ** | 0.51 ** | 0.30 ** | - | ||||

| 7. ES-ERS | 15.60 | 5.18 | 0.73 | 0.19 ** | 0.28 ** | −0.22 ** | −0.30 ** | −0.21 ** | 0.04 | - | |||

| 8. SCS | 17.96 | 4.37 | 0.93 | −0.57 ** | −0.60 ** | 0.48 ** | 0.63 ** | 0.48 ** | 0.64 ** | −0.18 ** | - | ||

| 9. CSR-SCS | 9.20 | 2.44 | 0.92 | −0.41 ** | −0.40 ** | 0.43 ** | 0.47 ** | 0.36 ** | 0.58 ** | −0.10 | 0.85 ** | - | |

| 10. RUSR-SCS | 8.79 | 2.65 | 0.92 | −0.56 ** | −0.63 ** | 0.40 ** | 0.61 ** | 0.45 ** | 0.52 ** | −0.20 ** | 0.87 ** | 0.87 ** | - |

| Pathway Tested | Indirect Effect |

|---|---|

| Negative Affect with CSR | |

| CSR > Cognitive Reappraisal > Negative Affect | −0.04 |

| CSR > Expressive Suppression > Negative Affect | 0.00 |

| Negative Affect with RUSR | |

| RUSR > Cognitive Reappraisal > Negative Affect | −0.03 |

| RUSR > Expressive Suppression > Negative Affect | −0.02 |

| Positive Affect with CSR | |

| CSR > Cognitive Reappraisal > Positive Affect | 0.11 ** |

| CSR > Expressive Suppression > Positive Affect | 0.00 |

| Positive Affect with RUSR | |

| RUSR > Cognitive Reappraisal > Positive Affect | 0.08 * |

| RUSR > Expressive Suppression > Positive Affect | 0.07 * |

| Psychological distress with CSR | |

| CSR > Cognitive Reappraisal > Psychological distress | −0.06 |

| CSR > Expressive Suppression > Psychological Distress | 0.00 |

| Psychological Distress with RUSR | |

| RUSR > Cognitive Reappraisal > Psychological Distress | −0.04 |

| RUSR > Expressive Suppression > Psychological Distress | −0.07 * |

| Psychological well-being with CSR | |

| CSR > Cognitive Reappraisal > Psychological Well-Being | 0.09 * |

| CSR > Expressive Suppression > Psychological Well-Being | 0.00 |

| Psychological Well-Being with RUSR | |

| RUSR > Cognitive Reappraisal > Psychological Well-Being | 0.06 * |

| RUSR > Expressive Suppression > Psychological Well-Being | 0.04 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ranjouri, S.; Meyer, D.; Bates, G.W. Self-Compassion Components and Emotional Regulation Strategies as Predictors of Psychological Distress and Well-Being. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1576. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111576

Ranjouri S, Meyer D, Bates GW. Self-Compassion Components and Emotional Regulation Strategies as Predictors of Psychological Distress and Well-Being. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(11):1576. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111576

Chicago/Turabian StyleRanjouri, Sepideh, Denny Meyer, and Glen William Bates. 2025. "Self-Compassion Components and Emotional Regulation Strategies as Predictors of Psychological Distress and Well-Being" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 11: 1576. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111576

APA StyleRanjouri, S., Meyer, D., & Bates, G. W. (2025). Self-Compassion Components and Emotional Regulation Strategies as Predictors of Psychological Distress and Well-Being. Behavioral Sciences, 15(11), 1576. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111576