When Loneliness Leads to Help-Seeking: The Role of Perceived Transactive Memory System and Work Meaningfulness

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Workplace Loneliness and Help-Seeking

2.2. Moderating Role of Transactive Memory System

2.3. Moderating Role of Work Meaningfulness

3. Method

3.1. Sample and Procedure

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. Help-Seeking Behavior

3.2.2. Workplace Loneliness

3.2.3. Perceived Transactive Memory System (TMS)

3.2.4. Work Meaningfulness

3.2.5. Control Variables

4. Results

5. Discussion

5.1. Overall Findings

5.2. Theoretical Implication

5.3. Practical Implication

5.4. Limitation and Future Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| COR | Conservation of Resources |

| TMS | Transactive Memory System |

| TPB | Theory of Planned Behavior |

References

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. (2002). Perceived behavioral control, self—Efficacy, locus of control, and the theory of planned behavior. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 32(4), 665–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, M. H. (2008). Social networks and the cognitive motivation to realize network opportunities: A study of managers’ information gathering behaviors. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 29(1), 51–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, S. E., & Williams, L. J. (1996). Interpersonal, job, and individual factors related to helping processes at work. Journal of Applied Psychology, 81(3), 282–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamberger, P. A. (2009). Employee help-seeking: Antecedents, consequences and new insights for future research. Research in Personnel and Human Resources Management, 28, 49–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blomqvist, S., Virtanen, M., Westerlund, H., & Magnusson Hanson, L. L. (2023). Associations between COVID-19-related changes in the psychosocial work environment and mental health. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 51(5), 664–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosco, F. A., Aguinis, H., Singh, K., Field, J. G., & Pierce, C. A. (2015). Correlational effect size benchmarks. Journal of Applied Psychology, 100(2), 431–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowler, W. M., & Brass, D. J. (2006). Relational correlates of interpersonal citizenship behavior: A social network perspective. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91(1), 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brislin, R. W. (1980). Translation and content analysis of oral and written material. In H. C. Triandis, & J. W. Berry (Eds.), Handbook of cross-cultural psychology (Vol. 2, pp. 389–444). Allyn and Bacon. [Google Scholar]

- Bryan, B. T., Andrews, G., Thompson, K. N., Qualter, P., Matthews, T., & Arseneault, L. (2023). Loneliness in the workplace: A mixed-method systematic review and meta-analysis. Occupational Medicine, 73(9), 557–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacioppo, J. T., Cacioppo, S., & Boomsma, D. I. (2014). Evolutionary mechanisms for loneliness. Cognition & Emotion, 28(1), 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacioppo, J. T., & Hawkley, L. C. (2009). Perceived social isolation and cognition. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 13(10), 447–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacioppo, S., Grippo, A. J., London, S., Goossens, L., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2015). Loneliness: Clinical import and interventions. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 10, 238–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y. H., & Yoon, J. (2001). The origin and function of dynamic collectivism: An analysis of Korean corporate culture. Asia Pacific Business Review, 7(4), 70–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S. Y., Lee, H., & Yoo, Y. (2010). The impact of information technology and transactive memory systems on knowledge sharing, application, and team performance: A field study. MIS Quarterly, 34, 855–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleavenger, D., Gardner, W. L., & Mhatre, K. (2007). Help-seeking: Testing the effects of task interdependence and normativeness on employees’ propensity to seek help. Journal of Business and Psychology, 21(3), 331–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deckop, J. R., Cirka, C. C., & Andersson, L. M. (2003). Doing unto others: The reciprocity of helping behavior in organizations. Journal of Business Ethics, 47(2), 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, S. X., Zhu, F., & Shaffer, M. A. (2025). Missed connections: A resource-management theory to combat loneliness experienced by globally mobile employees. Journal of International Business Studies, 56(2), 230–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firoz, M., & Chaudhary, R. (2022). The impact of workplace loneliness on employee outcomes: What role does psychological capital play? Personnel Review, 51(4), 1221–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, F. J., & Lake, V. K. B. (2008). If you need help, just ask: Underestimating compliance with direct requests for help. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95(1), 128–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gabriel, A. S., Lanaj, K., & Jennings, R. E. (2021). Is one the loneliest number? A within-person examination of the adaptive and maladaptive consequences of leader loneliness at work. Journal of Applied Psychology, 106(10), 1517–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenhaus, J. H., & Powell, G. N. (2006). When work and family are allies: A theory of work-family enrichment. Academy of Management Review, 31(1), 72–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halbesleben, J. R. B., Neveu, J.-P., Paustian-Underdahl, S. C., & Westman, M. (2014). Getting to the “COR”: Understanding the role of resources in conservation of resources theory. Journal of Management, 40(5), 1334–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkley, L. C., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2010). Loneliness matters: A theoretical and empirical review of consequences and mechanisms. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 40(2), 218–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S. E. (1989). Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. American Psychologist, 44(3), 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hofmann, D. A., Lei, Z., & Grant, A. M. (2009). Seeking help in the shadow of doubt: The sensemaking processes underlying how nurses decide whom to ask for advice. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94(5), 1261–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hollingshead, A. B. (2001). Cognitive interdependence and convergent expectations in transactive memory. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 81(6), 1080–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, W., & Gajendran, R. S. (2018). Explaining dyadic expertise use in knowledge work teams: An opportunity–ability–motivation perspective. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 39(6), 796–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, W., Lee, E. K., & Son, J. (2020). The interactive effects of perceived expertise, team identification, and dyadic gender composition on task-related helping behavior in project teams. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice, 24(2), 88–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarvenpaa, S. L., & Majchrzak, A. (2008). Knowledge collaboration among professionals protecting national security: Role of transactive memories in ego-centered knowledge networks. Organization Science, 19(2), 260–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, L. W., & Lau, D. C. (2012). Feeling lonely at work: Investigating the consequences of unsatisfactory workplace relationships. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 23(20), 4265–4282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, F. (2002). The social costs of seeking help. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 38(1), 17–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, K. (2003). Measuring transactive memory systems in the field: Scale development and validation. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(4), 587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, K. (2004). Knowledge and performance in knowledge-worker teams: A longitudinal study of transactive memory systems. Management Science, 50(11), 1519–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lips-Wiersma, M., Haar, J., & Cooper-Thomas, H. D. (2023). Is meaningful work always a resource toward wellbeing? The effect of autonomy, security and multiple dimensions of subjective meaningful work on wellbeing. Personnel Review, 52(1), 321–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., Zhou, X., Liao, S., Liao, J., & Guo, Z. (2019). The influence of transactive memory system on individual career resilience: The role of taking charge and self-promotion. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(18), 3390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lowman, G. H., Kessler, S. R., & Pindek, S. (2024). The permeation of loneliness into the workplace: An examination of robustness and persistence over time. Applied Psychology, 73(3), 1212–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majchrzak, A., More, P. H. B., & Faraj, S. (2012). Transcending knowledge differences in cross-functional teams. Organization Science, 23(4), 951–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masi, C. M., Chen, H.-Y., Hawkley, L. C., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2011). A meta-analysis of interventions to reduce loneliness. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 15(3), 219–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- May, D. R., Gilson, R. L., & Harter, L. M. (2004). The psychological conditions of meaningfulness, safety and availability and the engagement of the human spirit at work. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 77(1), 11–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, J. M., Erdogan, B., Bauer, T. N., Kudret, S., & Campion, E. (2025). All the lonely people: An integrated review and research agenda on work and loneliness. Journal of Management. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreland, R. L., & Myaskovsky, L. (2000). Exploring the performance benefits of group training: Transactive memory or improved communication? Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 82(1), 117–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, E. W., See, K. E., & Pan, C. (2015). An approach-inhibition model of employee silence: The joint effects of personal sense of power and target openness. Personnel Psychology, 68(3), 547–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, I. K. S. (2024). The ‘loneliness’ epidemic: A new social determinant of health? Internal Medicine Journal, 54(3), 365–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozcelik, H., & Barsade, S. G. (2018). No employee an island: Workplace loneliness and job performance. Academy of Management Journal, 61(6), 2343–2366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J.-Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qualter, P., Vanhalst, J., Harris, R., Van Roekel, E., Lodder, G., Bangee, M., Maes, M., & Verhagen, M. (2015). Loneliness across the life span. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 10(2), 250–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosette, A. S., Mueller., J. S., & Lebel, R. D. (2015). Are male leaders penalized for seeking help? The influence of gender and asking behaviors on competence perceptions. The Leadership Quarterly, 26(5), 749–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosso, B. D., Dekas, K. H., & Wrzesniewski, A. (2010). On the meaning of work: A theoretical integration and review. Research in Organizational Behavior, 30, 91–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steger, M. F., Dik, B. J., & Duffy, R. D. (2012). Measuring meaningful work: The work and meaning inventory (WAMI). Journal of Career Assessment, 20(3), 322–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, K. W., & Velthouse, B. A. (1990). Cognitive elements of empowerment: An “interpretive” model of intrinsic task motivation. Academy of Management Review, 15(4), 666–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Rijt, J., Van den Bossche, P., van de Wiel, M. W. J., De Maeyer, S., Gijselaers, W. H., & Segers, M. S. R. (2013). Asking for help: A relational perspective on help seeking in the workplace. Vocations and Learning, 6(2), 259–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Vegt, G. S., Bunderson, J. S., & Oosterhof, A. (2006). Expertness diversity and interpersonal helping in teams: Why those who need the most help end up getting the least. Academy of Management Journal, 49(5), 877–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegner, D. M. (1987). Transactive memory: A contemporary analysis of the group mind. In B. Mullen, & G. R. Goethals (Eds.), Theories of group behavior (pp. 185–208). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, L. J., & Anderson, S. E. (1991). Job satisfaction and organizational commitment as predictors of organizational citizenship and in-role behaviors. Journal of Management, 17(3), 601–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, T. A., Cropanzano, R., & Bonett, D. G. (2007). The moderating role of employee positive well being on the relation between job satisfaction and job performance. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 12(2), 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrzesniewski, A., Dutton, J. E., & Debebe, G. (2003). Interpersonal sensemaking and the meaning of work. Research in Organizational Behavior, 25, 93–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, Z., Zhou, B., Liu, Z., & Zhang, J. (2024). How to cope with the impact of workplace loneliness on withdrawal behavior: The roles of trait mindfulness and servant leadership. Current Psychology, 43(34), 27495–27508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Model Structure | χ2 (df) | CFI | TLI | SRMR | RMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4-Factor Model: Seeking, Loneliness, Meaning, TMS | 367 (203) | 0.961 | 0.956 | 0.056 | 0.056 |

| 3-Factor: Seeking, Loneliness, Meaning + TMS | 604 (206) | 0.906 | 0.895 | 0.081 | 0.086 |

| 2-Factor: Seeking, Loneliness + Meaning + TMS | 1795 (208) | 0.625 | 0.584 | 0.198 | 0.171 |

| 1-Factor: All Items on Single Factor | 2380 (209) | 0.487 | 0.433 | 0.224 | 0.200 |

| Mean | S.D. | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Gender | 0.50 | 0.50 | - | ||||||

| (2) Education Level | 2.64 | 0.85 | −0.09 | - | |||||

| (3) Current Tenure (years) | 7.96 | 7.44 | −0.01 | −0.05 | - | ||||

| (4) Self-rated Job Performance | 3.74 | 0.52 | −0.03 | 0.17 ** | 0.10 | - | |||

| (5) Perceived TMS | 3.54 | 0.49 | −0.03 | 0.18 ** | 0.04 | 0.44 ** | - | ||

| (6) Work Meaningfulness | 3.60 | 0.69 | −0.04 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.39 ** | 0.44 ** | - | |

| (7) Workplace Loneliness | 2.38 | 0.82 | −0.01 | −0.06 | −0.02 | −0.22 ** | −0.22 ** | −0.25 ** | - |

| (8) Help-Seeking | 2.95 | 0.78 | −0.13 * | −0.10 | −0.09 | 0.02 | 0.34 ** | 0.20 ** | −0.03 |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coeff. (S.E.) | 95% C.I. [LL, UL] | Coeff. (S.E.) | 95% C.I. [LL, UL] | Coeff. (S.E.) | 95% C.I. [LL, UL] | Coeff. (S.E.) | 95% C.I. [LL, UL] | Coeff. (S.E.) | 95% C.I. [LL, UL] | Coeff. (S.E.) | 95% C.I. [LL, UL] | |

| Intercept | 2.95 ** (0.05) | [2.85, 3.04] | 2.95 ** (0.05) | [2.85, 3.04] | 2.95 ** (0.04) | [2.86, 3.04] | 2.97 ** (0.04) | [2.88, 3.06] | 2.98 ** (0.05) | [2.89, 3.07] | 2.99 ** (0.04) | [2.90, 3.08] |

| Gender | −0.20 * (0.10) | [−0.39, −0.01] | −0.20 * (0.10) | [−0.39, −0.01] | −0.19 * (0.09) | [−0.36, −0.01] | −0.20 * (0.09) | [−0.38, −0.03] | −0.22 * (0.09) | [−0.40, −0.05] | −0.22 * (0.09) | [−0.40, −0.05] |

| Education level | 0.08 (0.06) | [−0.03, 0.19] | 0.08 (0.06) | [−0.04, 0.19] | 0.05 (0.05) | [−0.06, 0.15] | 0.05 (0.05) | [−0.06, 0.15] | 0.04 (0.05) | [−0.07, 0.14] | 0.04 (0.05) | [−0.06, 0.14] |

| Current tenure (years) | −0.01 (0.01) | [−0.02, 0.00] | −0.01 (0.01) | [−0.02, 0.00] | −0.01 (0.01) | [−0.02, 0.00] | −0.01 (0.01) | [−0.02, 0.00] | −0.01 (0.01) | [−0.02, 0.00] | −0.01 (0.01) | [−0.02, 0.00] |

| Self-rated Performance | 0.01 (0.09) | [−0.17, 0.20] | 0.01 ( 0.10) | [−0.19, 0.19] | −0.28 ** (0.10) | [−0.48, −0.08] | −0.27 ** (0.10) | [−0.47, −0.08] | −0.27 ** (0.10) | [−0.47, −0.08] | −0.27 ** (0.10) | [−0.46, −0.08] |

| Workplace Loneliness | −0.02 (0.06) | [−0.14, 0.10] | 0.04 (0.06) | [−0.07, 0.15] | 0.03 (0.06) | [−0.08, 0.14] | 0.03 (0.06) | [−0.08, 0.15] | 0.03 (0.06) | [−0.08, 0.14] | ||

| Perceived TMS | 0.61 ** (0.11) | [0.39, 0.82] | 0.56 ** (0.11) | [0.34, 0.77] | 0.58 ** (0.11) | [0.37, 0.79] | 0.55 ** (0.11) | [0.34, 0.77] | ||||

| Work Meaningfulness | 0.13 (0.08) | [−0.02, 0.28] | 0.12 (0.07) | [−0.03, 0.26] | 0.11 (0.08) | [−0.04, 0.26] | 0.11 (0.07) | [−0.04, 0.25] | ||||

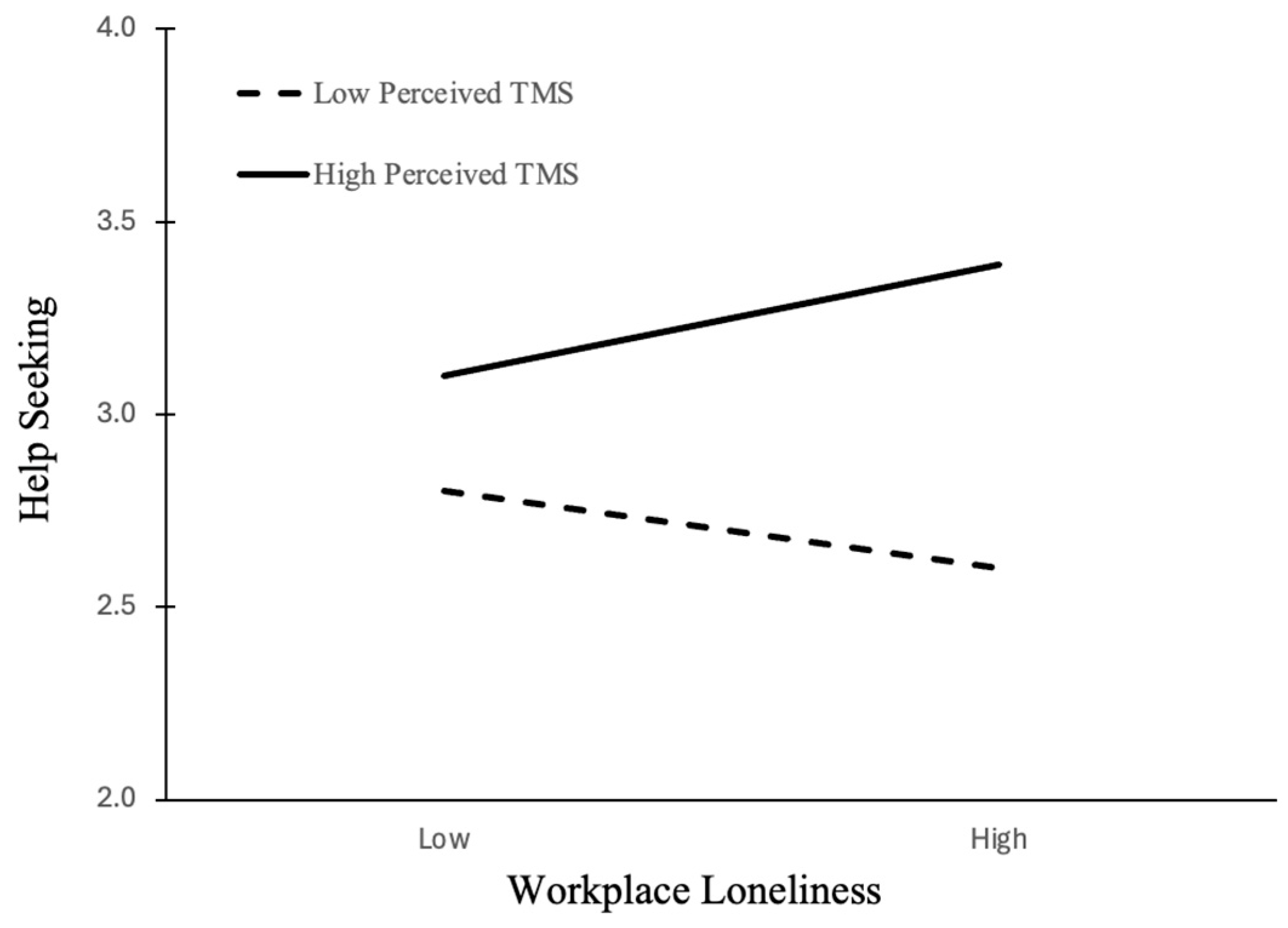

| Workplace Loneliness × TMS | 0.30 ** (0.09) | [0.12, 0.47] | 0.22 ** (0.10) | [0.04, 0.41] | ||||||||

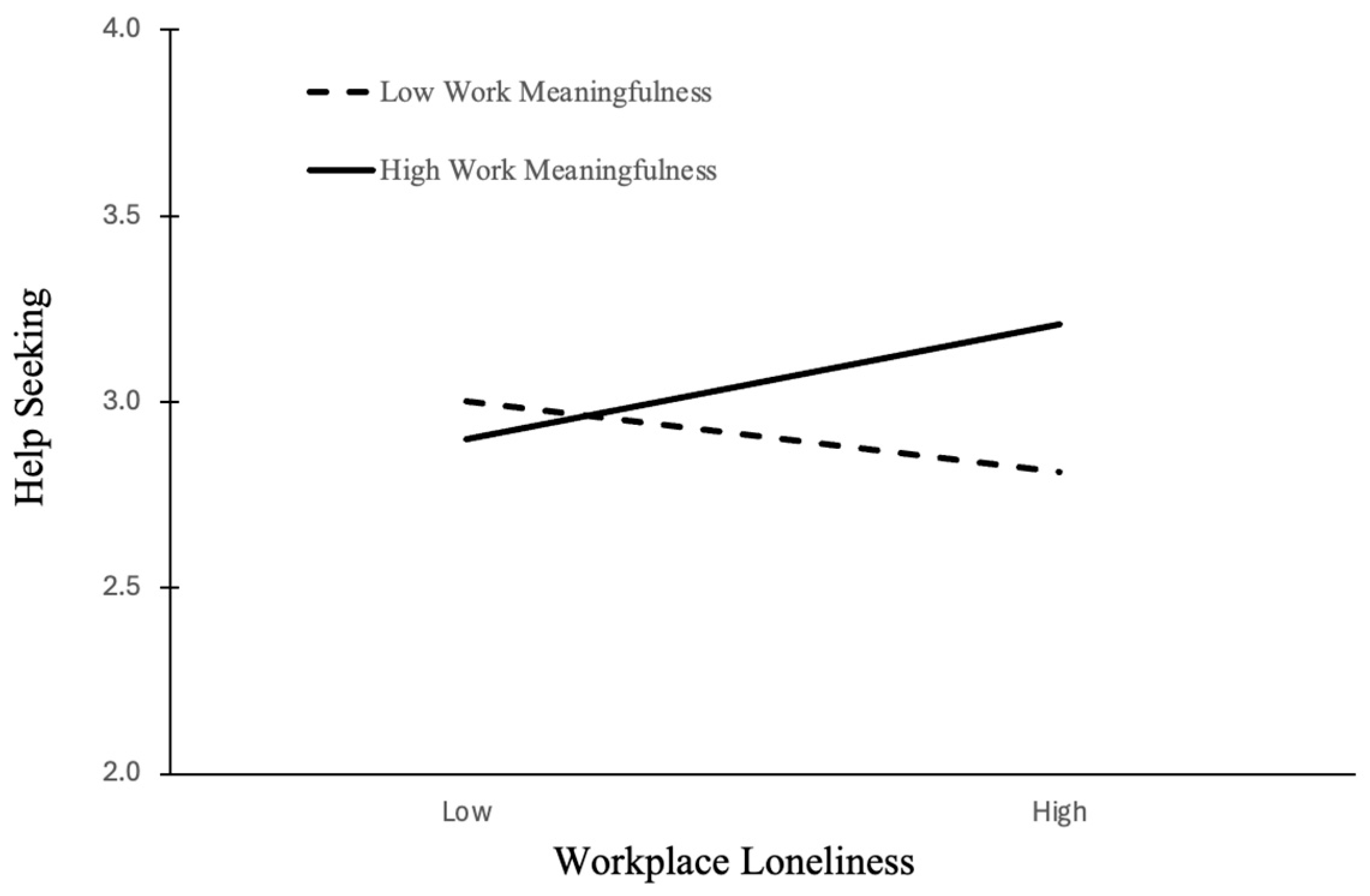

| Workplace Loneliness × Work Meaningfulness | 0.23 ** (0.07) | [0.08, 0.37] | 0.15 * (0.07) | [0.00, 0.31] | ||||||||

| R2 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.18 | 0.21 | 0.21 | 0.22 | ||||||

| ΔR2 | 0.00 | 0.14 ** | 0.04 ** | 0.03 ** | 0.05 ** | |||||||

| Slope | S.E. | |

|---|---|---|

| Mean − 1 SD | −0.11 | 0.07 |

| Mean + 1 SD | 0.18 * | 0.07 |

| Slope | S.E. | |

|---|---|---|

| Mean − 1 SD | −0.12 | 0.08 |

| Mean + 1 SD | 0.19 * | 0.07 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, S.; Hong, W. When Loneliness Leads to Help-Seeking: The Role of Perceived Transactive Memory System and Work Meaningfulness. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1506. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111506

Lee S, Hong W. When Loneliness Leads to Help-Seeking: The Role of Perceived Transactive Memory System and Work Meaningfulness. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(11):1506. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111506

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Sujin, and Woonki Hong. 2025. "When Loneliness Leads to Help-Seeking: The Role of Perceived Transactive Memory System and Work Meaningfulness" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 11: 1506. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111506

APA StyleLee, S., & Hong, W. (2025). When Loneliness Leads to Help-Seeking: The Role of Perceived Transactive Memory System and Work Meaningfulness. Behavioral Sciences, 15(11), 1506. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111506