Table Tennis in Physical Education: Teachers’ Perceptions of Health-Related Aspects in School-Age Children

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.4. Instruments

2.5. Procedure

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Analysis

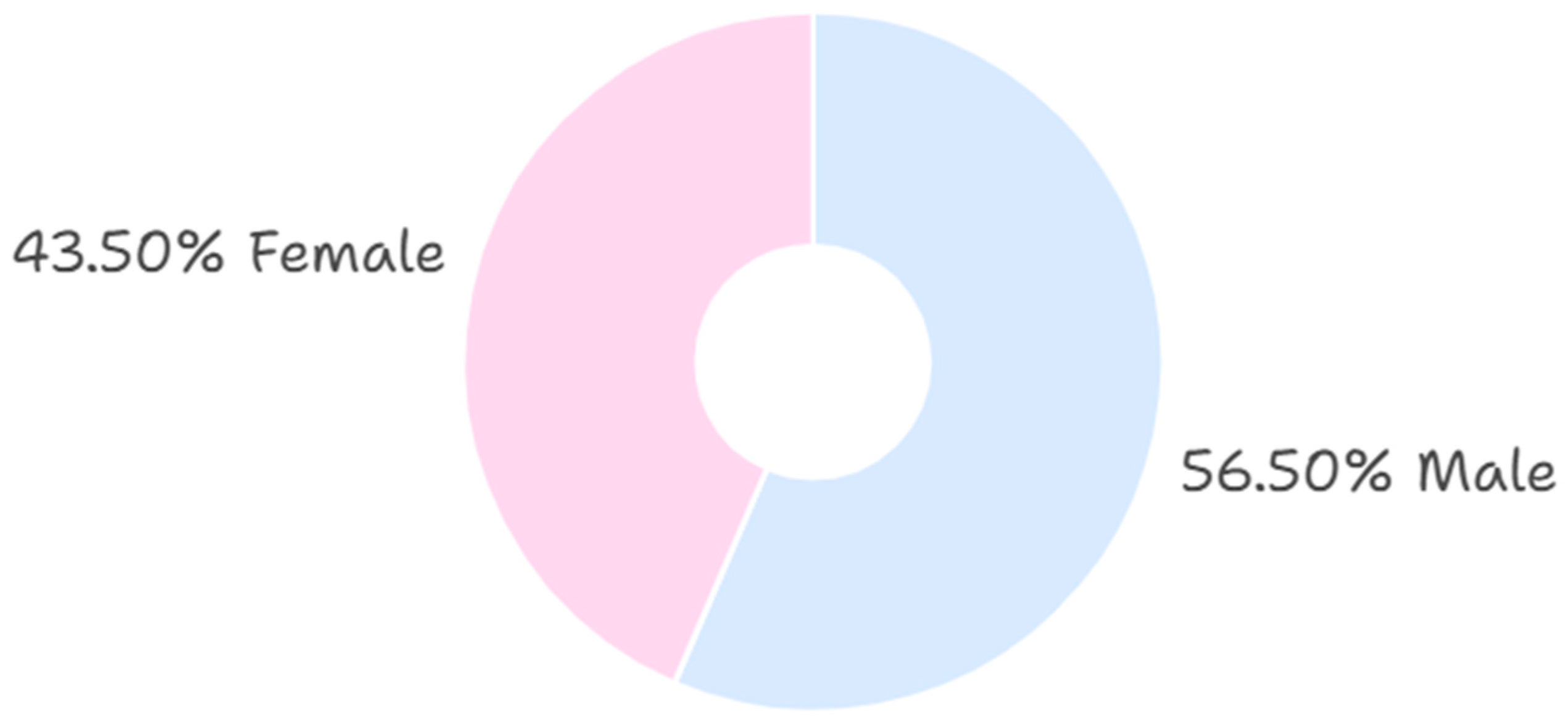

3.2. Sex Differences

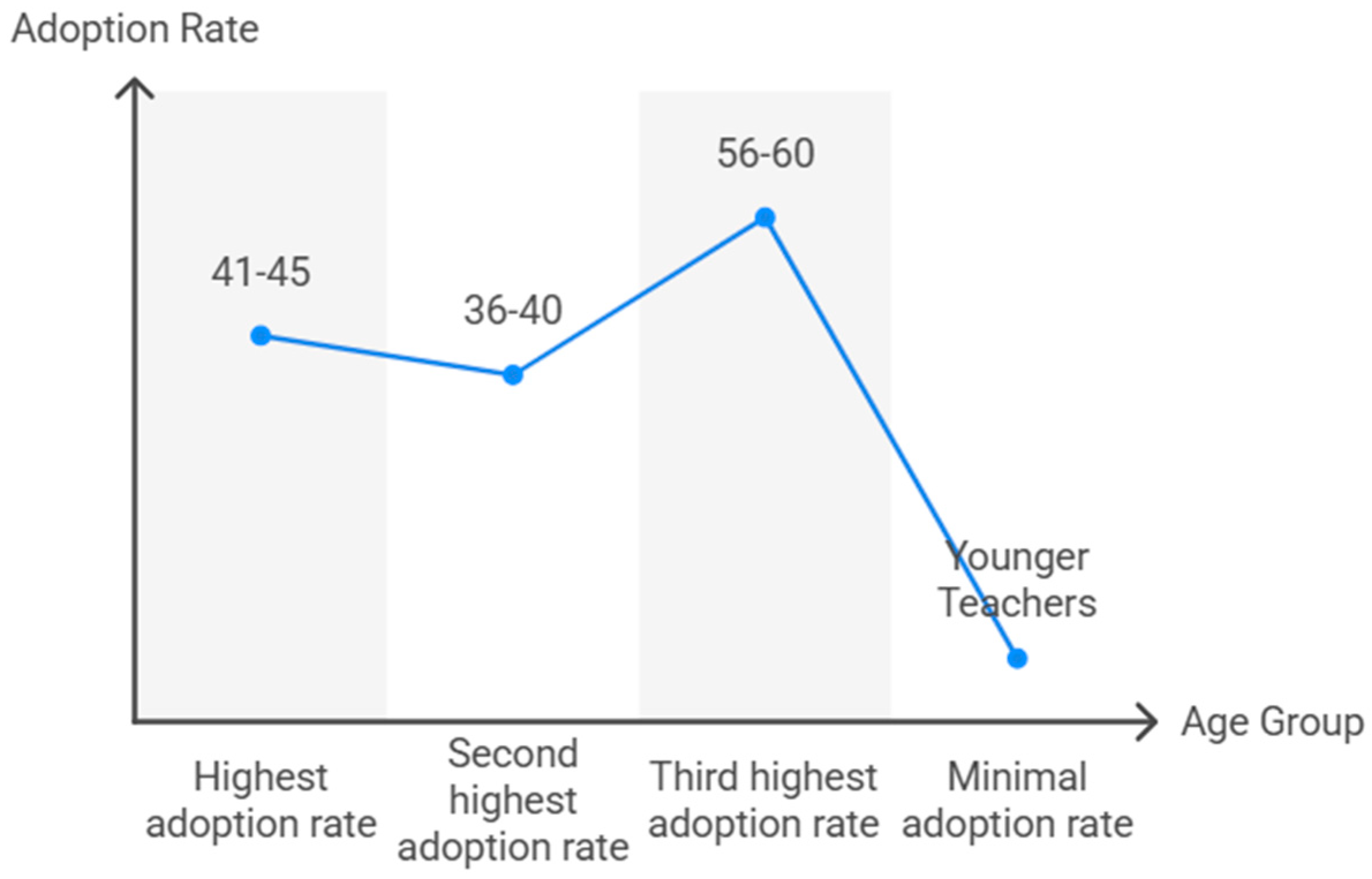

3.3. Age Distribution

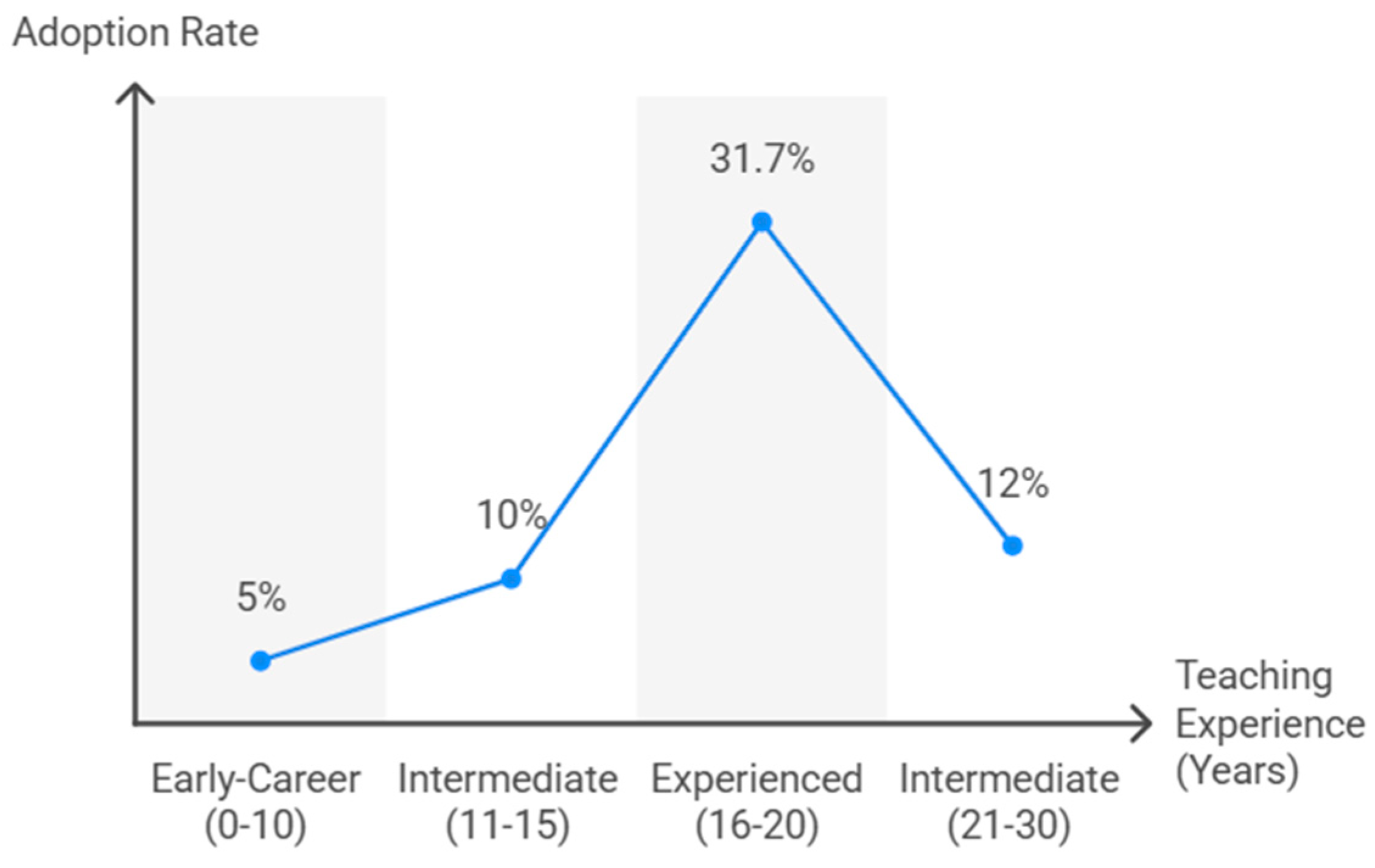

3.4. Teaching Experience

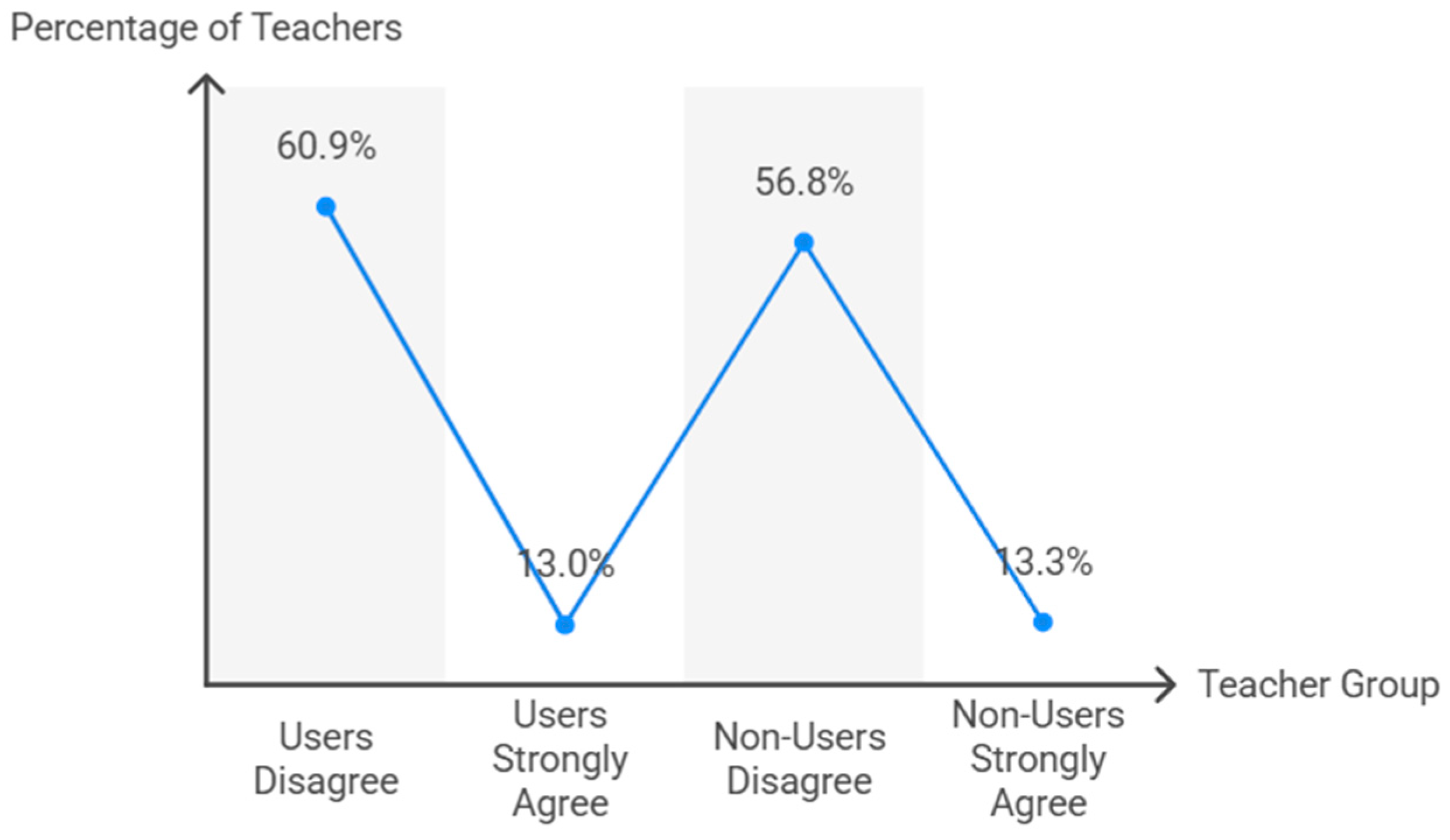

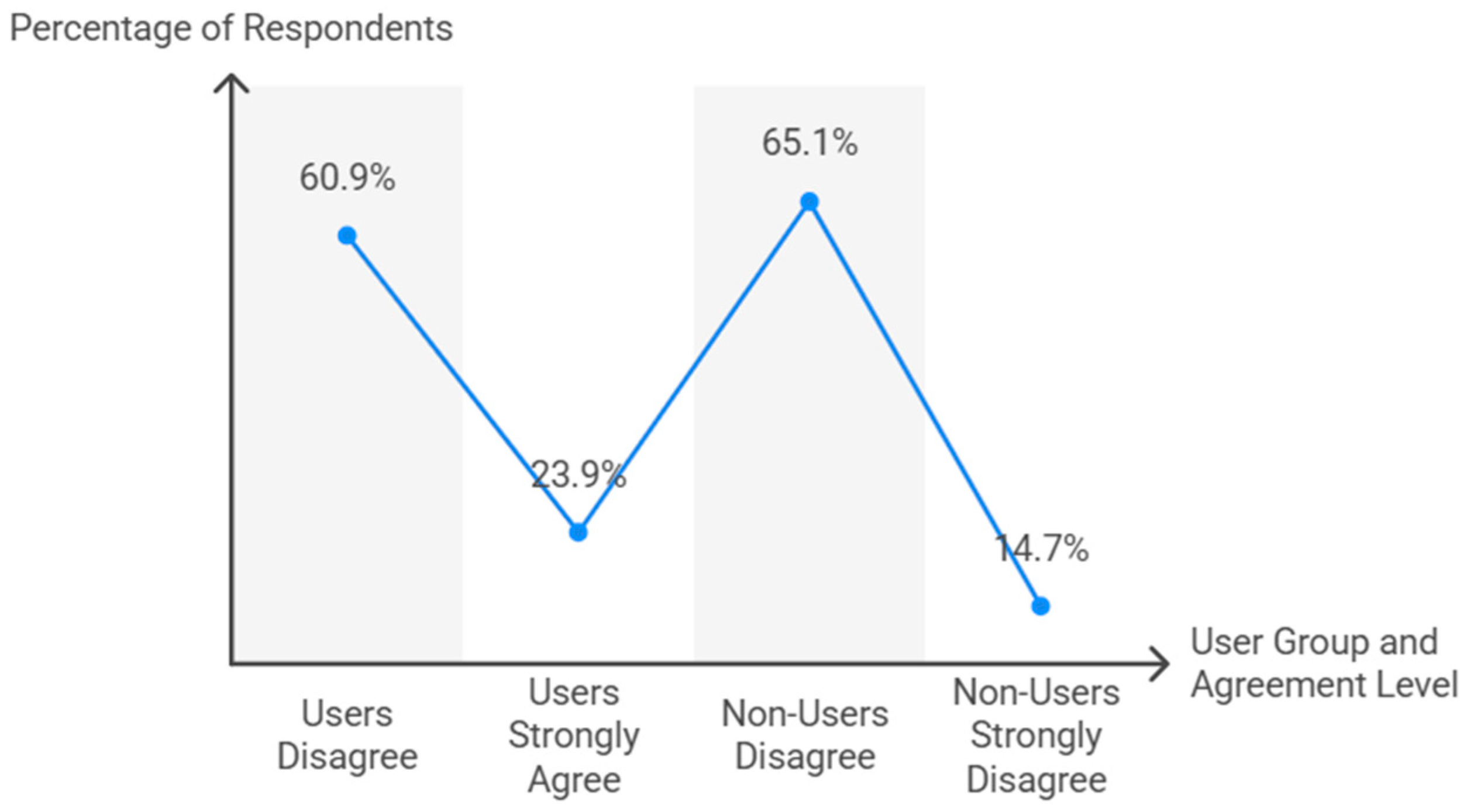

3.5. Perception of Injury Risk

3.6. Perceived Suitability for Students with Physical Disabilities

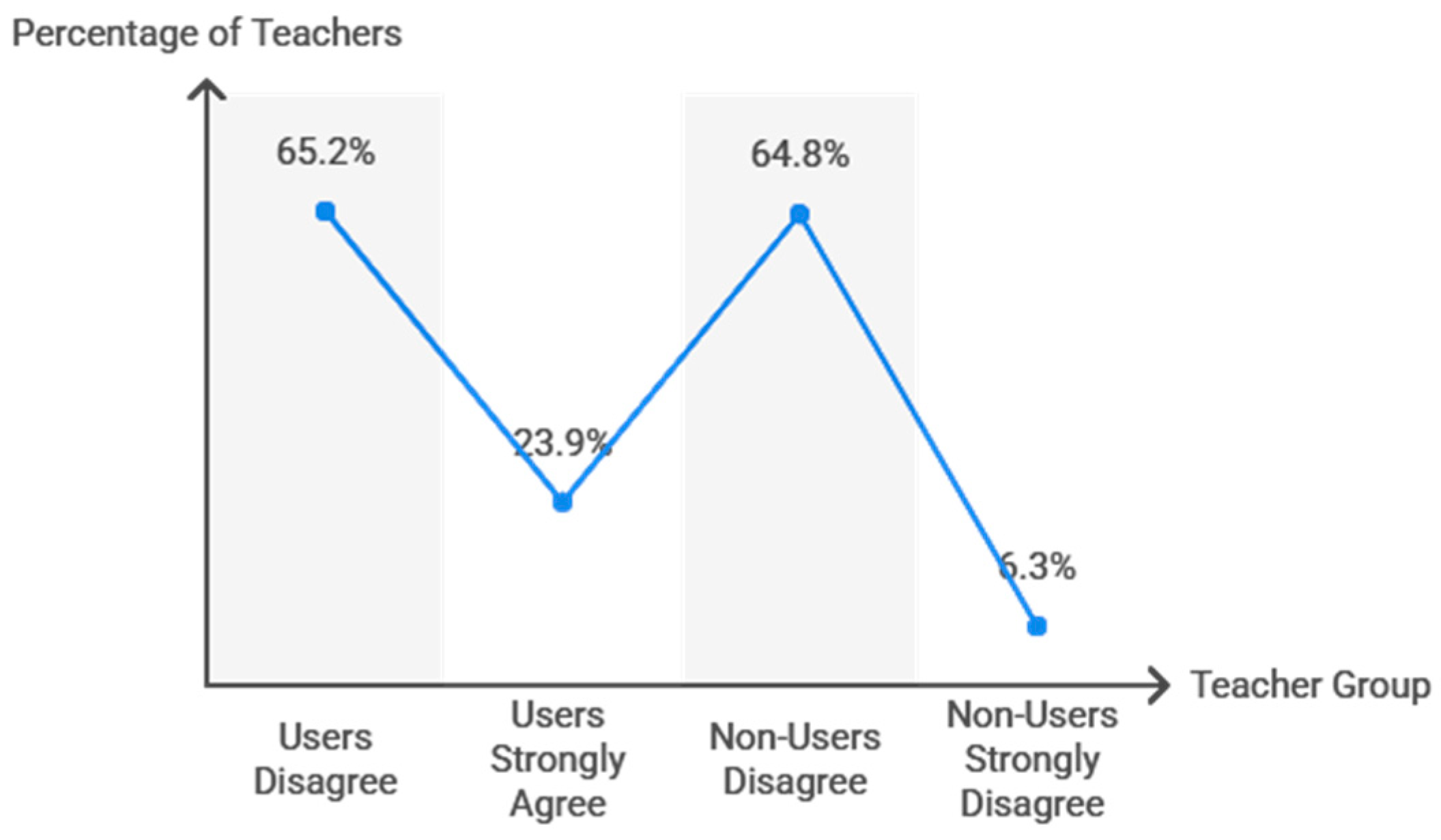

3.7. Perceived Suitability for Students with Special Educational Needs

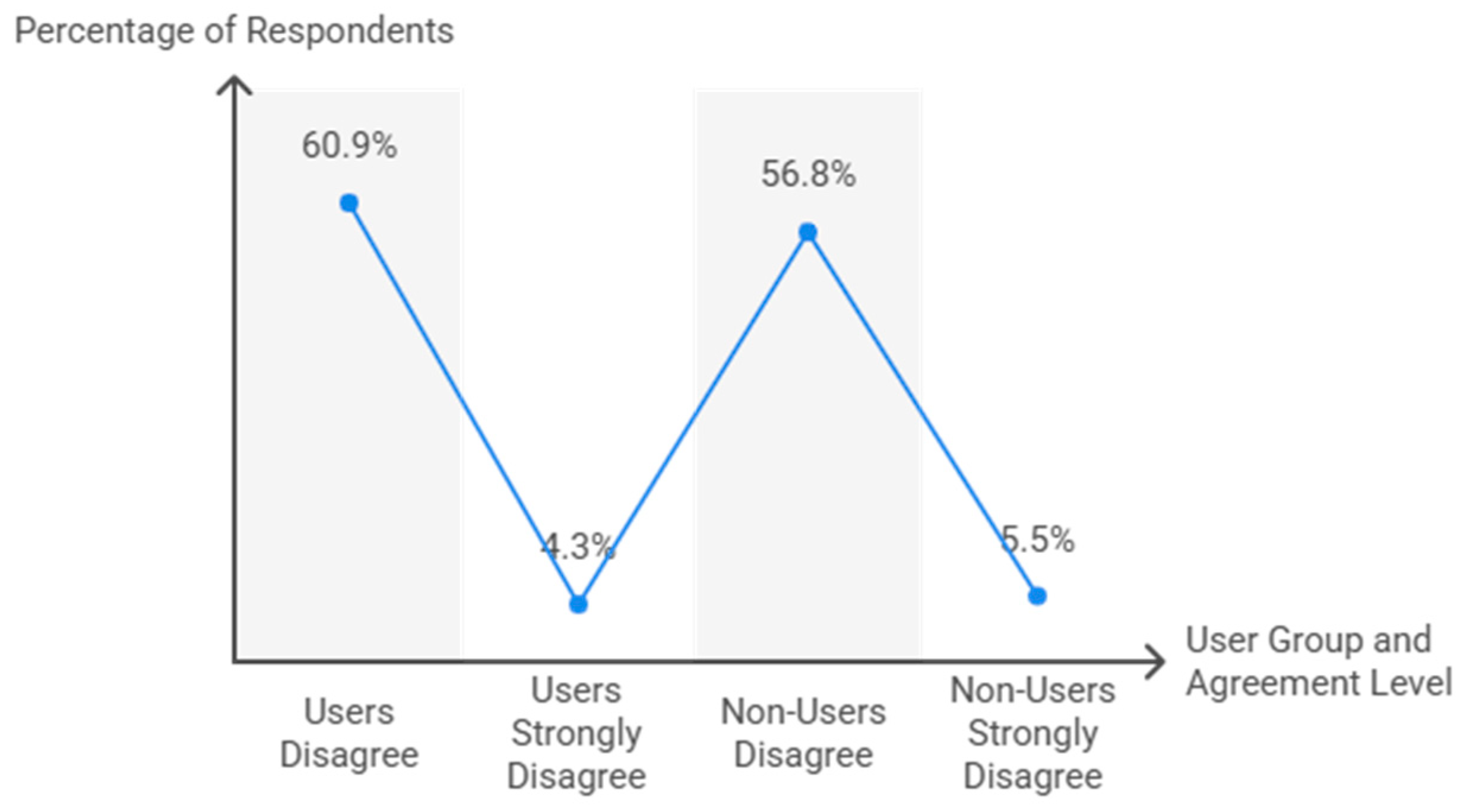

3.8. Perceived Safety in Primary Education

3.9. Perceived Student Engagement

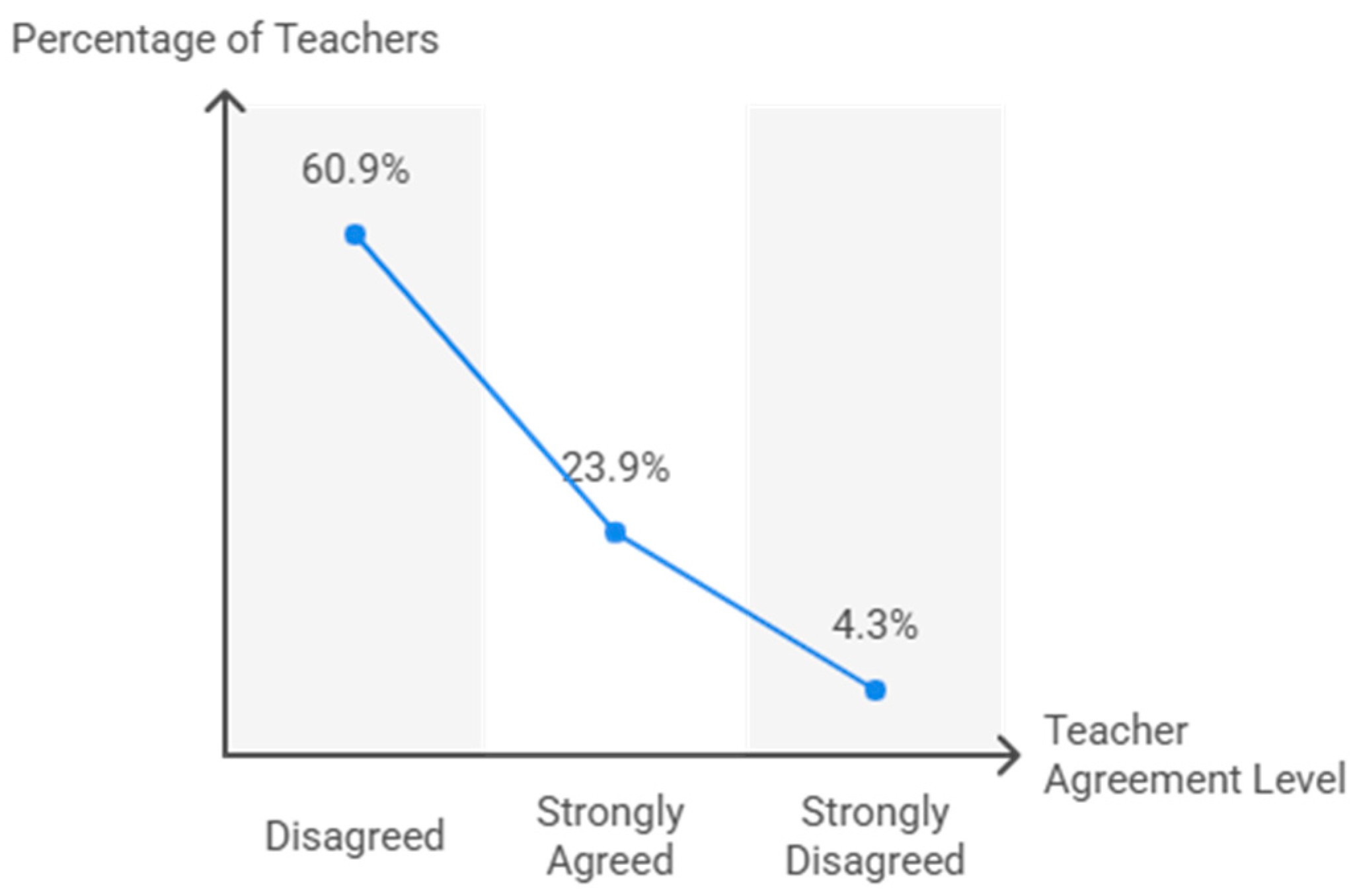

3.10. Perception of TT as a Recommended PE Content

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PE | Physical Education |

| RSAS | Racket Sports Attitude Scale |

| TT | Table Tennis |

References

- Abedanzadeh, R., Becker, K., & Mousavi, S. M. R. (2022). Both a holistic and external focus of attention enhance the learning of a badminton short serve. Psychological Research, 86(1), 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljaafreh, O. J. (2024). Measuring the level of knowledge of the international law of table tennis among physical education teachers in Al-Karak. Sport i Turystyka. Środkowoeuropejskie Czasopismo Naukowe, 7(1), 93–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydin, İ., & Akay, B. (2025). Parental perspectives on table tennis as an inclusive physical activity for children with autism: A qualitative means-end chain analysis. International Journal of Developmental Disabilities, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bechar, I., & Grosu, E. F. (2015). An applicable physical activity program affecting physiological and motor skills: The case of table tennis players participating in special Olympics (SO). Procedia—Social and Behavioral Sciences, 209, 247–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biernat, E., Buchholtz, S., & Krzepota, J. (2018). Eye on the ball: Table tennis as a pro-health form of leisure-time physical activity. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(4), 738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bull, F. C., Al-Ansari, S. S., Biddle, S., Borodulin, K., Buman, M. P., Cardon, G., Carty, C., Chaput, J.-P., Chastin, S., Chou, R., Dempsey, P. C., DiPietro, L., Ekelund, U., Firth, J., Friedenreich, C. M., Garcia, L., Gichu, M., Jago, R., Katzmarzyk, P. T., … Willumsen, J. F. (2020). World Health Organization 2020 guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 54(24), 1451–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cece, V. (2020). Mental training program in racket sports: A systematic review. International Journal of Racket Sports Science, 2(1), 55–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaput, J.-P., Willumsen, J., Bull, F., Chou, R., Ekelund, U., Firth, J., Jago, R., Ortega, F. B., & Katzmarzyk, P. T. (2020). 2020 WHO guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour for children and adolescents aged 5–17 years: Summary of the evidence. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 17(1), 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coe, D. P., Post, E. M., Fitzhugh, E. C., Fairbrother, J. T., & Webster, E. K. (2024). Associations among motor competence, physical activity, perceived motor competence, and aerobic fitness in 10–15-year-old youth. Children, 11(2), 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council of Europe. (1997). Convention for the protection of human rights and dignity of the human being with regard to the application of biology and medicine: Convention on human rights and biomedicine. European Treaty Series No. 164. The Secretary General of the Council of Europe. Available online: https://rm.coe.int/168007cf98 (accessed on 30 December 2023).

- Courel Ibáñez, J., Sánchez-Alcaraz Martín, B. J., García Benítez, S., & Echegaray, M. (2017). Evolution of padel in Spain according to practitioners’ gender and age. Cultura_Ciencia_Deporte, 12(34), 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Tejerina, D., & Fernández-Río, J. (2023). El modelo pedagógico de educación física relacionado con la salud. Una revisión sistemática siguiendo las directrices PRISMA [Health-based physical education model. A systematic review according to PRISMA guidelines]. Retos, 51, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnelly, J. E., & Lambourne, K. (2011). Classroom-based physical activity, cognition, and academic achievement. Preventive Medicine, 52, S36–S42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elferink-Gemser, M. T., Faber, I. R., Visscher, C., Hung, T.-M., De Vries, S. J., & Nijhuis-Van Der Sanden, M. W. G. (2018). Higher-level cognitive functions in Dutch elite and sub-elite table tennis players. PLoS ONE, 13(11), e0206151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Devesa, D., Sanchez-Lastra, M. A., Pintos-Barreiro, M., & Ayán-Pérez, C. (2024). Benefits of table tennis for children and adolescents: A narrative review. Children, 11(8), 963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Paniagua, S., Castillo-Paredes, A., Olivares, P. R., & Rojo-Ramos, J. (2025). Promoting mental health in adolescents through physical education: Measuring life satisfaction for comprehensive development. Children, 12(5), 658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y., Chen, Y., Ma, J., Ren, Z., Li, H., & Kim, H. (2021). The influence of a table tennis physical activity program on the gross motor development of Chinese preschoolers of different sexes. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(5), 2627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadler, R., Chiviacowsky, S., Wulf, G., & Schild, J. F. G. (2014). Children’s learning of tennis skills is facilitated by external focus instructions. Motriz: Revista de Educação Física, 20(4), 418–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healy, S. (2013). Adapting equipment for teaching object control skills. Physics Education, 27(4), 37–43. [Google Scholar]

- Herrero Pagán, R., Pradas de la Fuente, F., Castellar Otín, C., & Diaz, A. (2016). Análisis de la situación del tenis de mesa como contenido de educación física en Educación Secundaria Obligatoria. Journal of Sport and Health Research, 8(3), 245–258. [Google Scholar]

- Herrero Pagán, R., Pradas de la Fuente, F., Montero-Marin, J., Castellar, C., & Diaz, A. (2017). Actitud del profesorado de educación física hacia la práctica del tenis de mesa como contenido en Educación Secundaria. Habilidad Motriz, 49, 26–37. [Google Scholar]

- Herrero Pagán, R., Pradas de la Fuente, F., Rapún López, M., Peñarrubia Lozano, C., & Castellar Otín, C. (2018). Análisis de la situación de los deportes de raqueta y pala en educación física en la etapa de educación secundaria en Murcia. Revista Española de Educación Física y Deportes, 420, 59–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, W. K. Y., Ahmed, M. D., & Kukurova, K. (2021). Development and validation of an instrument to assess quality physical education. Cogent Education, 8(1), 1864082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, D., Brixius, K., & Vogt, T. (2018). Racket sports teaching implementations in physical education—A status quo analysis of German primary schools. Journal of Physical Education and Sport, 18, 867–873. [Google Scholar]

- Horníková, H., Doležajová, L., & Zemková, E. (2018). Playing table tennis contributes to better agility performance in middle-aged and older subjects. Acta Gymnica, 48(1), 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilkim, M., & Akyol, B. (2018). Effect of table tennis training on reaction times of down-syndrome children. Universal Journal of Educational Research, 6(11), 2399–2403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D., Roh, W., Lee, Y., & Yim, S. (2024). The effect of a table tennis exercise program with a task-oriented approach on visual perception and motor performance of adolescents with developmental coordination disorder. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 131(4), 1183–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koedijker, J., Oudejans, R., & Beek, P. (2007). Explicit rules and direction of attention in learning and performing the table tennis forehand. International Journal of Sport Psychology, 38, 227–244. [Google Scholar]

- Kondric, M., Matković, B. R., Furjan-Mandić, G., Hadzić, V., & Dervisević, E. (2011). Injuries in racket sports among Slovenian players. Collegium Antropologicum, 35(2), 413–417. [Google Scholar]

- Lees, A. (2003). Science and the major racket sports: A review. Journal of Sports Sciences, 21(9), 707–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ługowska, K., Kolanowski, W., & Trafialek, J. (2023). Increasing physical activity at school improves physical fitness of early adolescents. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(3), 2348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, S. R., Sims, C. A., Odabasi, A., Simonne, A., Gao, Z., Chase, C. A., Meru, G., & MacIntosh, A. J. (2023). Chemical and physical properties of winter squash and their correlation with liking of their sensory attributes. Journal of Food Science, 88(11), 4440–4456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulhearn, S. C., Kulinna, P. H., & Lorenz, K. A. (2024). Classroom teachers’ perceived barriers to implementing comprehensive school physical activity programs (TPB-CSPAP): Instrument development. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 95(2), 342–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mutlu Bozkurt, T. (2023). The relationship between table tennis athletes attitudes towards sports and Academic Achievemen. International Journal of Education Technology and Scientific Researches, 24, 2847–2860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opstoel, K., Chapelle, L., Prins, F. J., De Meester, A., Haerens, L., Van Tartwijk, J., & De Martelaer, K. (2020). Personal and social development in physical education and sports: A review study. European Physical Education Review, 26(4), 797–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organic Law 3/2020, of 29 December, amending Organic Law 2/2006, of 3 May, on Education. (2020, December 30). BOE Nº. 340. Available online: https://www.boe.es/eli/es/lo/2020/12/29/3 (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Ortega-Zayas, M. A., Cardona-Linares, A. J., Lecina, M., Ochiana, N., García-Giménez, A., & Pradas, F. (2025). Table tennis as a tool for physical education and health promotion in primary schools: A systematic review. Sports, 13(8), 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Zayas, M. Á., Cardona-Linares, A. J., Quílez, A., García-Giménez, A., Lecina, M., & Pradas, F. (2025). Development and validation of a questionnaire for table tennis teaching in physical education. Frontiers in Psychology, 16, 1550061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, C.-Y., Chu, C.-H., Tsai, C.-L., Lo, S.-Y., Cheng, Y.-W., & Liu, Y.-J. (2016). A racket-sport intervention improves behavioral and cognitive performance in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 57, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pradas de la Fuente, F., & Castellar Otín, C. (2016). El tratamiento didáctico del tenis de mesa como contenido en educación física. Revista Pedagógica ADAL, 33, 32–38. [Google Scholar]

- Pradas de la Fuente, F., & Herrero Pagán, R. (2015). La iniciación deportiva. In Fundamentos del tenis de mesa. Aplicación al ámbito escolar (pp. 145–175). EDIT.UM, Universidad de Murcia, Servicio de Publicaciones. [Google Scholar]

- Pradas, F., Ara, I., Toro, V., & Courel-Ibáñez, J. (2021). Benefits of regular table tennis practice in body composition and physical fitness compared to physically active children aged 10–11 years. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(6), 2854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Alcaraz, B. J., & Courel-Ibáñez, J. (2022). The role of padel in improving physical fitness and health promotion: Progress, limitations, and future perspectives—A narrative review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(11), 6582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starzak, M., Niźnikowski, T., Biegajło, M., Nogal, M., Arnista, W. Ł., Mastalerz, A., & Starzak, A. (2024). Attentional focus strategies in racket sports: A systematic review. PLoS ONE, 19(1), e0285239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teraoka, E., & Yotsumoto, E. (2024). The educational value and implementation challenges of teaching table tennis in physical education. Strategies, 37(5), 51–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation. (2015). Quality physical education (QPE): A guide for policy makers. UNESCO. Available online: https://www.sport-for-development.com/imglib/downloads/Guidelines/unesco2015-en-quality-physical-education-guidelines-for-policy-makers.pdf (accessed on 30 December 2024).

- World Medical Association. (2013). World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA, 310(20), 2191–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wulf, G., McNevin, N., & Shea, C. H. (2001). The automaticity of complex motor skill learning as a function of attentional focus. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology Section A, 54(4), 1143–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wulf, G., Shea, C., & Lewthwaite, R. (2010). Motor skill learning and performance: A review of influential factors: Motor skill learning and performance. Medical Education, 44(1), 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Category | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Female | 176 | 35.8 |

| Male | 217 | 44.1 | |

| School environment | Urban | 252 | 51.2 |

| Rural | 141 | 28.7 | |

| School type | Public | 242 | 49.2 |

| Private | 12 | 2.4 | |

| Subsidized | 139 | 28.3 | |

| Professional role | Teacher | 239 | 46.5 |

| Tutor | 129 | 20.5 | |

| Other | 24 | 4.9 | |

| Administrative status | Awaiting placement | 7 | 1.4 |

| Interim | 75 | 14.8 | |

| Permanent Physical Education post | 292 | 59.1 | |

| Other | 19 | 3.9 |

| Variable | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 39.6 | 9.16 |

| Teaching experience (years) | 13.4 | 9.11 |

| Variable | χ2 (df) | p-Value | Association Strength |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 492.0 (4) | <0.001 | Cramer’ V = 0.707 |

| Age group | 27.2 (7) | <0.001 | Somers’ D = 0.071 |

| Teaching experience | 30.0 (6) | <0.001 | Somers’ D = 0.099 |

| Perception of Injury Risk | 496.1 (8) | <0.001 | Somers’ D = 0.575 |

| Perceived Suitability for Students with Physical Disabilities | 505.6 (8) | <0.001 | Somers D = 0.599 |

| Perceived Suitability for Students with Special Educational Needs | 502.9 (8) | <0.001 | Somers’ D = 0.578 |

| Perceived Safety in Primary Education | 492.4 (8) | <0.001 | Somers’ D = 0.574 |

| Perceived Student Engagement | 499.2 (8) | <0.001 | Somers’ D = 0.594 |

| Perception of Table Tennis as a Recommended PE Content | 504.9 (8) | <0.001 | Somers’ D = 0.586 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ortega-Zayas, M.Á.; Patanè, P.; Peñarrubia-Lozano, C.; Pradas, F. Table Tennis in Physical Education: Teachers’ Perceptions of Health-Related Aspects in School-Age Children. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1495. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111495

Ortega-Zayas MÁ, Patanè P, Peñarrubia-Lozano C, Pradas F. Table Tennis in Physical Education: Teachers’ Perceptions of Health-Related Aspects in School-Age Children. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(11):1495. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111495

Chicago/Turabian StyleOrtega-Zayas, Miguel Ángel, Pamela Patanè, Carlos Peñarrubia-Lozano, and Francisco Pradas. 2025. "Table Tennis in Physical Education: Teachers’ Perceptions of Health-Related Aspects in School-Age Children" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 11: 1495. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111495

APA StyleOrtega-Zayas, M. Á., Patanè, P., Peñarrubia-Lozano, C., & Pradas, F. (2025). Table Tennis in Physical Education: Teachers’ Perceptions of Health-Related Aspects in School-Age Children. Behavioral Sciences, 15(11), 1495. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111495