Three-Character Training of Question-Asking (TCT-Q) for Children with High-Functioning Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Randomized Controlled Trial

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Session Planning and Preparation of Training Materials

2.2. Participants

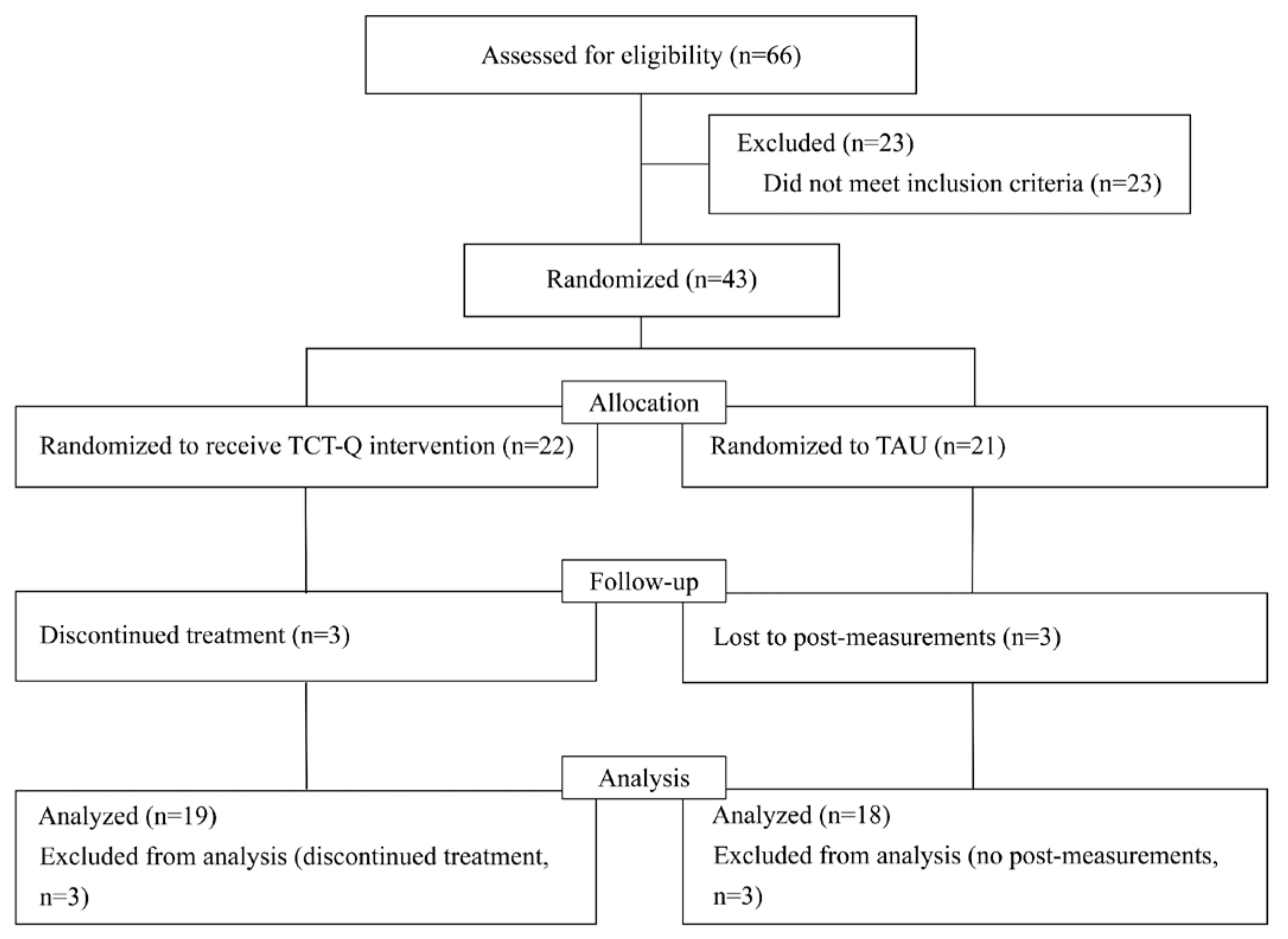

2.3. RCT

2.4. Measures

2.4.1. Assessment Measures

- Autism Diagnostic. ASD symptoms of the participants were evaluated using the ADOS-2, which is a standardized, semi-structured assessment tool (Lord et al., 2012). Only children with scores at or above the autism spectrum cut-off were eligible to participate in the study.

- Intellectual ability. IQ was assessed using the Chinese version of WPPSI-IV or WISC-IV (Li & Zhu, 2014; H. Zhang, 2008). The population mean of IQ and index scores is 100, with a standard deviation of 15. The retest reliabilities of the Chinese version of the WPPSI-IV or WISC-IV (r = 0.76–0.91) and the inter-rater coefficients (0.96–0.99) are both satisfactory (Li & Zhu, 2014; H. Zhang, 2009).

2.4.2. Feasibility Measures

- Fidelity of Implementation. Fidelity of Implementation (FoI) consists of 10 items, each scored as ‘0’ (fail) or ‘1’ (success). FoI assesses the complete implementation of the intervention process, correct feedback from the teacher on child/caregiver behavior, child’s cooperation with the session, and the child’s appropriate demonstration of skills in different contexts. A psychology graduate student assessed FoI on a random 25% of the TCT-Q session videos. An FoI score of ≥80% is considered acceptable (McGarry et al., 2020).

- Intervention Credibility. The intervention credibility measure, designed by the researchers, consisted of a total of five questions. At T2 and T3, psychology graduate students conducted structured interviews with caregivers. The interview questions focused on the children’s question-asking and social behaviors in daily life, as well as caregivers’ feedback on the TCT-Q training.

2.4.3. Outcome Measures

- Primary outcome measuresNumber of question-asking. The numbers of children’s question-asking were assessed at all three time points (T1, T2, and T3). Each time, the teacher conducted a structured social interaction with the child, providing a total of 60 opportunities for the child to ask the target questions. Then, a caregiver was asked to interact with the child in a five-minute free-play activity as they would usually do, and was required to induce the child to ask as many target questions as possible they could. The interactions between the teacher/caregiver and child were videotaped, and the number of questions children asked was counted.

- Secondary outcome measures

- (1)

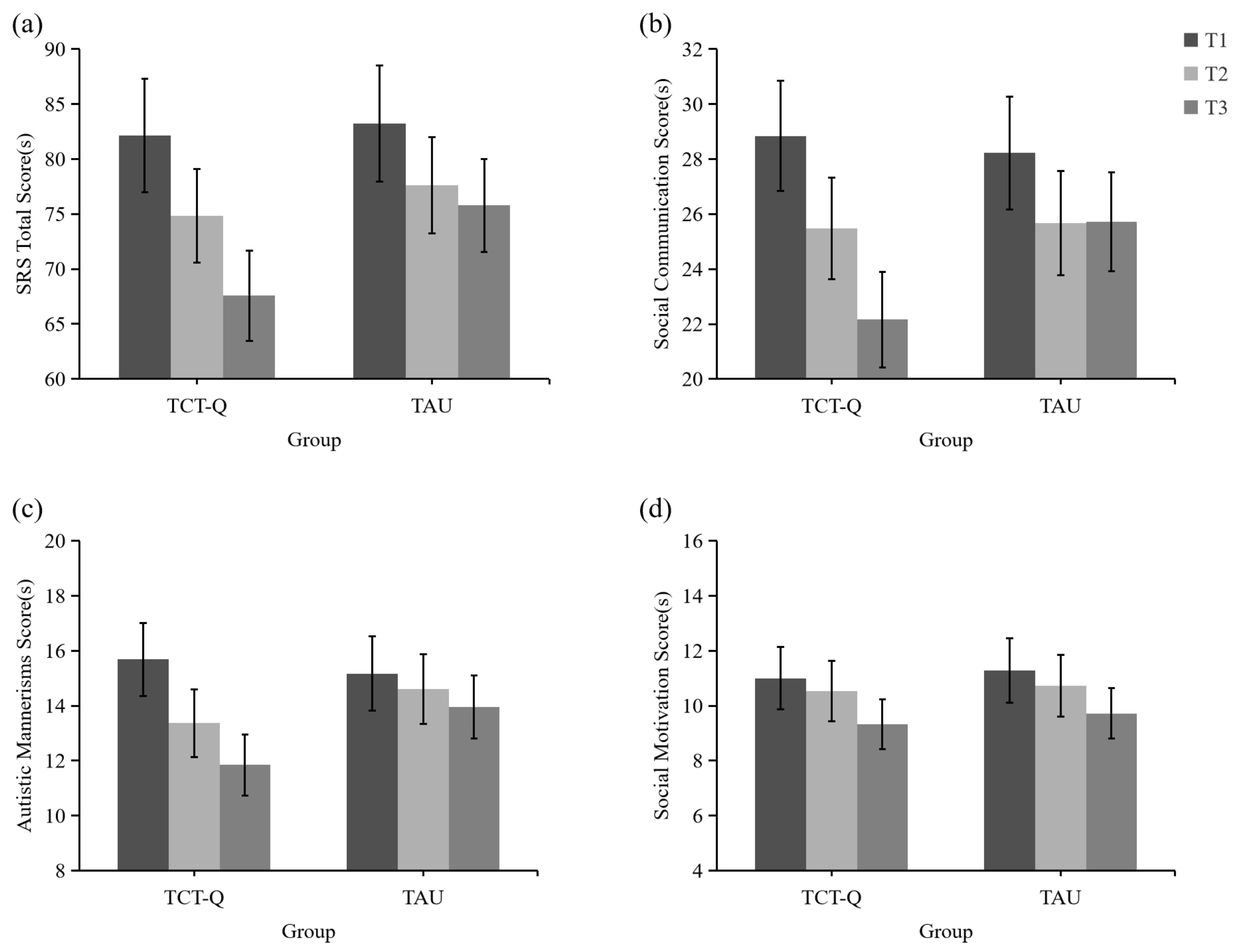

- Social skills. The present study used the Chinese version of the Social Responsiveness Scale (SRS) for children (Cen et al., 2017). The SRS consists of 65 items, including five subscales (labeled social awareness, social cognition, social communication, social motivation, and autistic mannerisms), which are used to assess the social interaction ability of children with ASD (Constantino & Gruber, 2012). The lower the score, the less the degree of difficulty in social interaction for the individual. Caregivers completed the SRS at all three time points (T1, T2, and T3). The reliability of the total SRS score in the current study was 0.92.

- (2)

- Parenting stress. The Chinese version of Parenting Stress Index-Short Form (PSI-SF) (Ren, 1995), with a total of 36 items, was used to assess the levels of perceived parenting stress. The reliability of the total PSI-SF score in the current study was 0.93.

2.4.4. Reliability Measures

2.5. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

3.2. Feasibility

3.3. Primary Outcome

3.3.1. Teacher–Child Interaction

3.3.2. Caregiver–Child Interaction

3.4. Secondary Outcome

3.4.1. Social Skills

3.4.2. Parenting Stress

3.5. Reliability

4. Discussion

4.1. Increased Question-Asking

4.2. Improvement of Social Skills

4.3. Caregiver Involvement

4.4. Strengths and Weaknesses of the Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| TCT-Q | Three-character training in question-asking |

| HFASD | High-functioning autism spectrum disorder |

| TAU | Treatment as usual |

| ASD | Autism spectrum disorder |

| CBT | Cognitive behavioral therapy |

| RCT | Randomized controlled trial |

| ADOS-2 | Autism diagnostic observation schedule, second edition |

| IQ | Intelligence quotient |

| WPPSI-IV | Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence-Fourth Edition |

| WISC-IV | Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children-Fourth Edition |

| FoI | Fidelity of Implementation |

| SRS | Social responsiveness scale |

| PSI-SF | Parenting Stress Index-Short Form |

| IOA | Interobserver agreement |

| T-C | Teacher–child |

| C-C | Caregiver–child |

References

- Bozkus-Genc, G., & Yucesoy-Ozkan, S. (2021). The efficacy of pivotal response treatment in teaching question-asking initiations to young Turkish children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 51(11), 3868–3886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradshaw, J., Wolfe, K., Hock, R., & Scopano, L. (2022). Advances in supporting parents in interventions for autism spectrum disorder. Pediatric Clinics of North America, 69(4), 645–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bross, L. A., Huffman, J. M., Anderson, A., Alhibs, M., Rousey, J. G., & Pinczynski, M. (2022). Technology-based self-monitoring and visual supports to teach question asking skills to young adults with autism in community settings. Journal of Special Education Technology, 38(4), 458–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cen, C. Q., Liang, Y. Y., Chen, Q. R., Chen, K. Y., Deng, H. Z., Chen, B. Y., & Zou, X. B. (2017). Investigating the validation of the Chinese Mandarin version of the Social Responsiveness Scale in a Mainland China child population. BMC Psychiatry, 17, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2025). Prevalence and early identification of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 4 and 8 years—Autism and developmental disabilities monitoring network, 16 sites, United States, 2022. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/74/ss/ss7402a1.htm?s_cid=ss7402a1_w (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Constantino, J. N., & Gruber, C. P. (2012). Social responsiveness scale (SRS) manual. Western Psychological Services. [Google Scholar]

- Dalton, K. M., Nacewicz, B. M., Johnstone, T., Schaefer, H. S., Gernsbacher, M. A., Goldsmith, H. H., Alexander, A. L., & Davidson, R. J. (2005). Gaze fixation and the neural circuitry of face processing in autism. Nature Neuroscience, 8, 519–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dawson, G., Franz, L., & Brandsen, S. (2022). At a crossroads—Reconsidering the goals of autism early behavioral intervention from a neurodiversity perspective. JAMA Pediatrics, 176(9), 839–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Detar, W. J., & Vernon, T. W. (2020). Targeting question-asking initiations in college students with ASD using a video-feedback intervention. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 35(4), 208–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diehl, J., Tang, K., & Thomas, B. (2013). Encyclopedia of autism spectrum disorders. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, X., Wu, J., Li, D., & Liu, Z. (2024). The benefit of rhythm-based interventions for individuals with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis with random controlled trials. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 15, 1436170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doggett, R. A., Krasno, A. M., Koegel, L. K., & Koegel, R. L. (2013). Acquisition of multiple questions in the context of social conversation in children with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 43, 2015–2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A.-G., & Buchner, A. (2007). G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39(2), 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gantman, A., Kapp, S. K., Orenski, K., & Laugeson, E. A. (2012). Social skills training for young adults with high-functioning autism spectrum disorders: A randomized controlled pilot study. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 42(6), 1094–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grove, R., Hoekstra, R. A., Wierda, M., & Begeer, S. (2018). Special interests and subjective wellbeing in autistic adults. Autism Research, 11(5), 766–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, X., Zheng, Q., & Lee, G. T. (2018). Using peer-mediated LEGO® play intervention to improve social interactions for Chinese children with autism in an inclusive setting. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 48(7), 2444–2457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huo, C., Li, Z., & Meng, J. (2021). Empathy interventions for individuals with autism spectrum disorders: Giving full play to strengths or making up for weaknesses? Advances in Psychological Science, 29(5), 849–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, O. C., Heron, T. E., & Heward, W. L. (2012). Applied behavior analysis second edition. Wuhan University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Koegel, L. K., Park, M. N., & Koegel, R. L. (2014). Using self-management to improve the reciprocal social conversation of children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44, 1055–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowitt, J. S., Madaus, J., Simonsen, B., Freeman, J., Lombardi, A., & Ventola, P. (2025). Implementing pivotal response treatment to teach question asking to high school students with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 55, 3065–3077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laugeson, E. A., Frankel, F., Gantman, A., Dillon, A. R., & Mogil, C. (2012). Evidence-based social skills training for adolescents with autism spectrum disorders: The UCLA PEERS® program. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 42, 1025–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laugeson, E. A., Gantman, A., Kapp, S. K., Orenski, K., & Ellingsen, R. (2015). A randomized controlled trial to improve social skills in young adults with autism spectrum disorder: The UCLA PEERS® program. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 45(12), 3978–3989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y., & Zhu, J. (2014). The Chinese version of the Wechsler preschool and primary scale of intelligence-4th edition. King-May Psychological Assessment Technology & Development Limited Company. [Google Scholar]

- Lord, C., Rutter, M., DiLavore, P. C., Risi, S., Gotham, K., & Bishop, S. L. (2012). Autism diagnostic observation schedule, second edition (ADOS-2) manual: Modules 1–4. Western Psychological Services. [Google Scholar]

- Mason, R. A., Gregori, E., Wills, H. P., Kamps, D., & Huffman, J. (2020). Covert audio coaching to increase question asking by female college students with autism: Proof of concept. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 32(1), 75–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matson, J. L., & Sturmey, P. (Eds.). (2022). Handbook of autism and pervasive developmental disorder. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- McGarry, E., Vernon, T., & Baktha, A. (2020). Brief report: A pilot online pivotal response treatment training program for parents of toddlers with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 50, 3424–3431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacia, C., Holloway, J., Gunning, C., & Lee, H. (2022). A systematic review of family-mediated social communication interventions for young children with autism. Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 9(2), 208–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patten, K. K. (2022). Finding our strengths: Recognizing professional bias and interrogating systems. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 76(6), 7606150010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popovic, S. C., Starr, E. M., & Koegel, L. K. (2020). Teaching initiated question asking to children with autism spectrum disorder through a short-term parent-mediated program. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 50, 3728–3738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pyles, M. L., Chastain, A. N., & Miguel, C. F. (2021). Teaching children with autism to mand for information using “why?” as a function of denied access. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior, 37(1), 17–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, W. (1995). Parenting stress, coping strategy and satisfaction of parent-child relations [Unpublished Master Dissertation, National Taiwan Normal University]. [Google Scholar]

- Stadnick, N. A., Stahmer, A., & Brookman-Frazee, L. (2015). Preliminary effectiveness of Project ImPACT: A parent-mediated intervention for children with autism spectrum disorder delivered in a community program. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 45, 2092–2104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strathearn, L., Kim, S., Bastian, D. A., Jung, J., Iyengar, U., Martinez, S., Goin-Kochel, R. P., & Fonagy, P. (2018). Visual systemizing preference in children with autism: A randomized controlled trial of intranasal oxytocin. Development and Psychopathology, 30(2), 511–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verschuur, R., Huskens, B., Verhoeven, L., & Didden, R. (2017). Increasing opportunities for question-asking in school-aged children with autism spectrum disorder: Effectiveness of staff training in pivotal response treatment. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 47, 490–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheelwright, S., Baron-Cohen, S., Goldenfeld, N., Delaney, J., Fine, D., Smith, R., Weil, L., & Wakabayashi, A. (2006). Predicting autism spectrum quotient (AQ) from the systemizing quotient-revised (SQ-R) and empathy quotient (EQ). Brain Research, 1079(1), 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whyte, E. M., Smyth, J. M., & Scherf, K. S. (2015). Designing serious game interventions for individuals with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 45(12), 3820–3831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, T., Miura, Y., Oi, M., Akatsuka, N., & Laugeson, E. A. (2020). Examining the treatment efficacy of peers in Japan: Improving social skills among adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 50(3), 976–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, H. J., Bahn, G., Cho, I. H., Kim, E. K., Kim, J. H., Min, J. W., Lee, W. H., Seo, J. S., Jun, S. S., Bong, G., Cho, S., Shin, M. S., Kim, B. N., Kim, J. W., Park, S., & Laugeson, E. A. (2014). A randomized controlled trial of the Korean version of the PEERS® parent-assisted social skills training program for adolescents with ASD. Autism Research, 7(1), 145–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H. (2008). The Chinese version of the Wechsler intelligence scale for children—4th edition. King-May Psychological Assessment Technology & Development Limited Company. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H. (2009). The revision of WISC-IV Chinese version. Psychological Science, 32(5), 1177–1179. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y. (2020). Teaching research and case design of the three-character classic from the perspective of international communication [Doctoral Dissertation, Hunan University]. [Google Scholar]

| Type | Theme | Mnemonic | Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|

| Simple | What’s this? | Ask the name, what is this 问名称,是什么 | When we want to know the name of something, we could ask, “What’s this?” |

| Events- Related | What did … (someone) do? | What someone did, ask what 知某事,做什么 | When we want to know what someone did, we could ask “What did … (someone) do?” |

| Social Interaction | Can I … (do something) with you? | Do it together, ask for the will 一起做,问意愿 | When we want to do something with someone, we could ask “Can I … (do something) with you?” |

| Procedure | Description of the Procedure |

|---|---|

| Review | The teacher reviews the previous session’s content with the child. |

| Introduction | The teacher introduces a new question along with the corresponding three-character mnemonic. |

| Game | The teacher and assistant play imaginative games with the child using toys that the child likes. Obstacles are set up in the game where children are expected to say the target question to receive rewards. |

| Video Modeling | A one-minute video is shown to the child, illustrating the correct way to ask an appropriate question in a given situation. Then, the teacher explains the video and discusses it with the child. |

| Role-Playing | The child and the assistant engage in role-playing, including imitating the video setting and two other everyday situations, with the teacher providing guidance and feedback. |

| Caregiver Practice | Under the instruction of the teacher, the caregiver plays games and engages in role-playing with the child. |

| Homework | The teacher provides feedback on the caregiver’s homework from the previous session and assigns new homework. |

| TCT-Q (n = 19) | TAU (n = 18) | t or χ2 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 6.58 ± 1.35 | 6.17 ± 1.25 | 0.964 | 0.341 |

| Gender, male | 18 | 16 | 0.424 | 0.515 |

| WISC-IV/ WPPSI-IV | 107.84 ± 19.07 | 107.22 ± 15.55 | 0.108 | 0.915 |

| ADOS-2 | 13.00 ± 4.97 | 12.89 ± 5.17 | 0.067 | 0.947 |

| Outcomes | TCT-Q | TAU | Time F | Group F | Time × Group F | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 M (SD) | T2 M (SD) | T3 M (SD) | T1 M (SD) | T2 M (SD) | T3 M (SD) | ||||

| Number of question-asking (T-C) | 17.42 (8.03) | 30.47 (8.43) | 27.74 (6.67) | 18.22 (8.77) | 18.39 (11.19) | 21.39 (10.03) | 29.31 *** | 4.74 * | 20.56 *** |

| Number of question-asking (C-C) | 2.05 (2.42) | 5.21 (4.17) | 3.68 (2.58) | 1.61 (1.50) | 2.28 (2.76) | 2.06 (2.41) | 8.07 ** | 5.28 * | 3.42 * |

| SRS Total | 82.16 (24.31) | 74.84 (20.55) | 67.58 (21.22) | 83.22 (20.31) | 77.61 (15.93) | 75.78 (13.66) | 9.57 *** | 0.48 | 1.09 |

| Social Awareness | 11.42 (3.73) | 10.79 (2.35) | 10.47 (2.76) | 11.89 (2.30) | 11.11 (1.91) | 10.94 (2.62) | 2.86 † | 0.32 | 0.02 |

| Social Cognition | 15.21 (5.91) | 14.68 (3.99) | 13.79 (4.85) | 16.67 (4.27) | 15.50 (3.85) | 15.44 (3.73) | 2.35 | 1.01 | 0.25 |

| Social Communication | 28.84 (10.35) | 25.47 (9.18) | 22.16 (8.95) | 28.22 (6.55) | 25.67 (6.68) | 25.72 (5.90) | 11.22 *** | 0.19 | 2.55 † |

| Social Motivation | 11.00 (4.75) | 10.53 (5.17) | 9.32 (4.79) | 11.28 (5.20) | 10.72 (4.32) | 9.72 (2.76) | 4.59 * | 0.05 | 0.02 |

| Autistic Mannerisms | 15.68 (5.14) | 13.37 (5.23) | 11.84 (5.26) | 15.17 (6.36) | 14.61 (5.52) | 13.94 (4.41) | 6.19 ** | 0.37 | 1.71 |

| PSI-SF | 93.58 (21.92) | 93.26 (21.34) | 91.90 (20.29) | 91.28 (19.94) | 89.06 (18.02) | 85.39 (16.34) | 2.29 | 0.50 | 0.59 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hu, W.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Yu, S.; Li, X. Three-Character Training of Question-Asking (TCT-Q) for Children with High-Functioning Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1489. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111489

Hu W, Wang Y, Zhang S, Yu S, Li X. Three-Character Training of Question-Asking (TCT-Q) for Children with High-Functioning Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(11):1489. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111489

Chicago/Turabian StyleHu, Wanxue, Yijie Wang, Siyuan Zhang, Siying Yu, and Xinying Li. 2025. "Three-Character Training of Question-Asking (TCT-Q) for Children with High-Functioning Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Randomized Controlled Trial" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 11: 1489. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111489

APA StyleHu, W., Wang, Y., Zhang, S., Yu, S., & Li, X. (2025). Three-Character Training of Question-Asking (TCT-Q) for Children with High-Functioning Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Behavioral Sciences, 15(11), 1489. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111489