Cognitive Correlates of Emotional Dispositions: Differentiating Trait Sadness and Trait Anger via Attributional Style and Helplessness

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Study 1-1: Development and Initial Validation of the Trait Sadness Scale (TSS)

2.1. Method

2.1.1. Item Generation and Content Validation

- Cognitive Appraisals: Tendencies to appraise situations in terms of loss, helplessness, and negative outcomes (e.g., “I often feel like things are hopeless”).

- Affective Experience: The propensity to experience the core feelings of sadness, gloom, and disappointment (e.g., “I feel downhearted quite often”).

- Motivational/Behavioral Tendencies: The inclination toward withdrawal, inaction, and expressions of distress (e.g., “When I’m upset, I prefer to be alone”).

- Relevance Rating: Rate the relevance of each item to the overarching construct of trait sadness on a 4-point scale (1 = not relevant, 2 = somewhat relevant, 3 = quite relevant, and 4 = highly relevant).

- Clarity Rating: Rate the clarity of each item’s wording on a 3-point scale (1 = unclear, 2 = needs minor revision, and 3 = very clear).

2.1.2. Participants

2.1.3. Measures

2.2. Results

2.2.1. Exploratory Factor Analysis and Item Reduction

- Factor 1: Affective Frequency (5 items): The general propensity to feel sad, dejected, and depressed.

- Factor 2: Cognitive Reactions (5 items): Cognitive patterns associated with sadness, such as feelings of helplessness and difficulty recovering from setbacks.

- Factor 3: Somatic & Behavioral Expressions (5 items): Somatic and action tendencies, such as crying and withdrawal.

2.2.2. Reliability

2.2.3. Preliminary Convergent and Discriminant Validity

3. Study 1-2: Confirmatory Factor Analysis and Construct Validation of the TSS

3.1. Method

3.1.1. Participants

3.1.2. Measures

3.2. Results

3.2.1. Confirmatory Factor Analysis of the TSS

3.2.2. Relationships with Personality and Emotion-Regulation Variables

4. Study 2: Emotional Disposition, Cognitive Appraisal, and Helplessness

4.1. Method

4.1.1. Participants

4.1.2. Procedure

4.1.3. Measures

4.2. Results

4.2.1. Preliminary Analyses

4.2.2. Replication of State-Level Emotion–Attribution Links

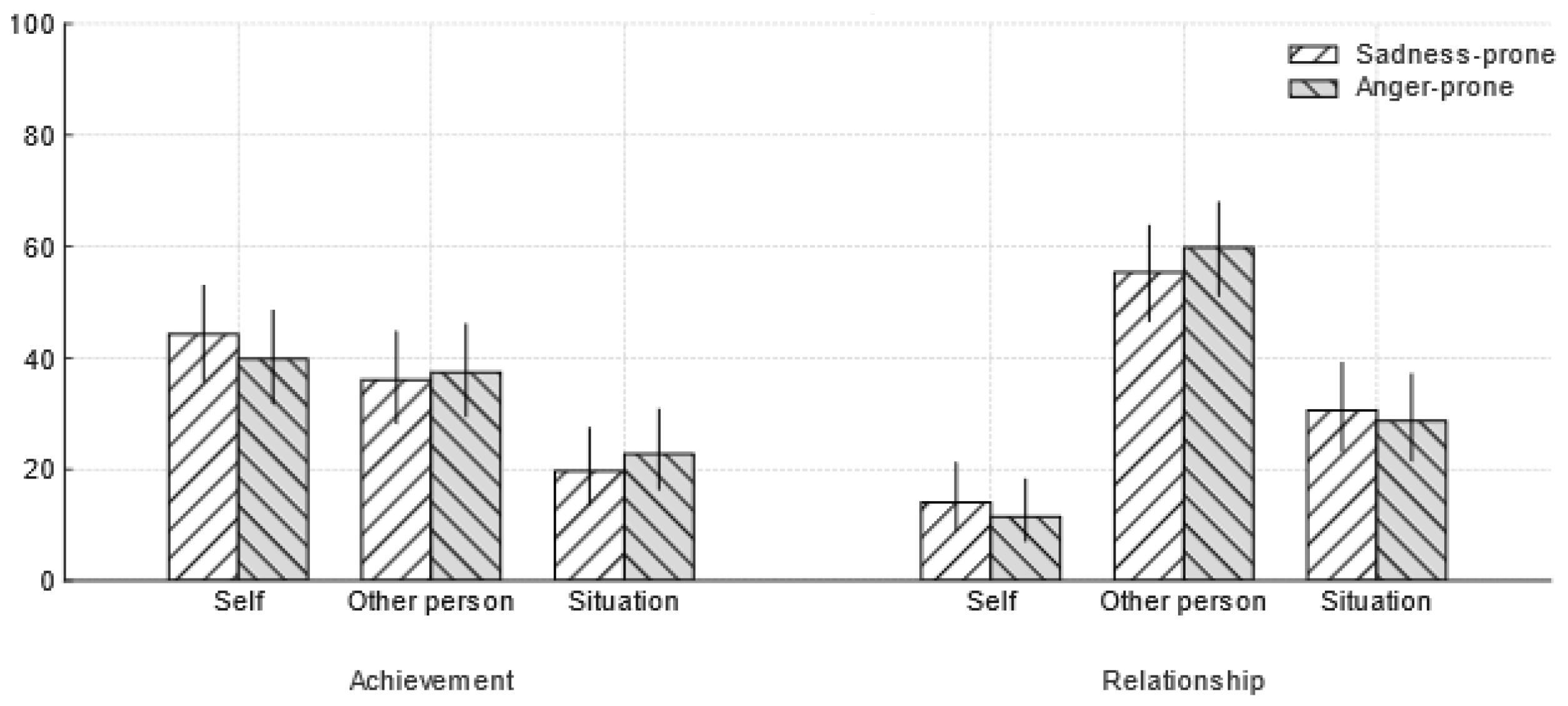

4.2.3. Emotional Disposition and Locus of Attribution

4.2.4. Emotional Disposition and Helplessness

4.2.5. Follow-Up Analysis of Attributional Style (LEAQ)

4.3. Discussion

5. General Discussion

5.1. The Central Finding: A State–Trait Dissociation

5.2. Implications and Alternative Mechanisms

5.3. Distinguishing Trait Sadness from Depression

5.4. Practical Implications

5.5. Limitations and Future Directions

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Full Text of Scenarios Used in Study 2

- Achievement-Oriented Scenario

- Relationship-Oriented Scenario

References

- Bae, H. N., Choi, S. W., Yu, J. C., Lee, J. S., & Choi, K. S. (2014). Reliability and validity of the Korean version of the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (K-RSES) in adult. Mood Emotion, 12(1), 43–49. [Google Scholar]

- Bernbau, H., Fujita, F., & Pfennig, J. (1995). Consistency, specificity, and correlates of negative emotions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 68(2), 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodenhausen, G. V., Sheppard, L. A., & Kramer, G. P. (1994). Negative affect and social judgment: The differential impact of anger and sadness. European Journal of Social Psychology, 24(1), 45–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondolfi, G., Mazzola, V., & Arciero, G. (2015). In between ordinary sadness and clinical depression. Emotion Review, 7(3), 216–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chon, K. K., Hahn, D. W., & Lee, C. H. (1998). Korean adaptation of the state-trait anger expression inventory (STAXI-K): The case of college students. The Korean Journal of Health Psychology, 3(1), 18–32. [Google Scholar]

- Damasio, A. R. (1994). Descartes’ error and the future of human life. Scientific American, 271(4), 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deffenbacher, J. L., Story, D. A., Brandon, A. D., Hogg, J. A., & Hazaleus, S. L. (1988). Cognitive and cognitive-relaxation treatments of anger. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 12(2), 167–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabbay, F. H. (1992). Behavior-genetic strategies in the study of emotion. Psychological Science, 3(1), 50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, H. Y. (1995). A study on the relationship among perfectionism, self-efficacy, and depression [Master’s thesis, Ewha Womans University]. [Google Scholar]

- Izard, C. E., Libero, D. Z., Putnam, P., & Haynes, O. M. (1993). Stability of emotion experiences and their relations to traits of personality. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 64(5), 847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keltner, D., Ellsworth, P. C., & Edwards, K. (1993). Beyond simple pessimism: Effects of sadness and anger on social perception. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 64(5), 740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S. J., & Lee, H. G. (1997). A study on the validation of the trait meta-mood scale: An exploration of the sub-factors of emotional intelligence. Korean Journal of Social and Personality Psychology, 11(1), 95–116. [Google Scholar]

- Lerner, J. S., & Keltner, D. (2001). Fear, anger, and risk. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 81(1), 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, L. J. (1995). Young children’s understanding of the causes of anger and sadness. Child Development, 66(3), 697–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.-Y., Lee, E.-J., Jeong, S.-W., Kim, H.-C., Jeong, C.-H., Jeon, T.-Y., Yi, M.-S., Kim, J.-M., Jo, H.-J., & Kim, J.-B. (2011). The validation study of the beck depression inventory–II (BDI–II) in Korean version. Anxiety and Mood, 7(1), 48–53. [Google Scholar]

- Min, K. H., Kim, J. H., Yoon, S. B., & Chang, S. M. (2000). A study on the regulation strategies for negative emotions: Differences in emotion regulation styles according to emotion types and individual variables. Korean Journal of Social and Personality Psychology, 14(2), 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Roseman, I. J., Wiest, C., & Swartz, T. S. (1994). Phenomenology, behaviors, and goals differentiate discrete emotions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67(2), 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salovey, P., Mayer, J. D., Goldman, S. L., Turvey, C., & Palfai, T. P. (1995). Emotional attention, clarity, and repair: Exploring emotional intelligence using the trait meta-mood scale. In J. W. Pennebaker (Ed.), Emotion, disclosure, & health (pp. 125–154). American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheier, M. F., Carver, C. S., & Bridges, M. W. (1994). Distinguishing optimism from neuroticism (and trait anxiety, self-mastery, and self-esteem): A reevaluation of the life orientation test. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67(6), 1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaver, P., Schwartz, J., Kirson, D., & O’connor, C. (1987). Emotion knowledge: Further exploration of a prototype approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52(6), 1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sherer, M., Maddux, J. E., Mercandante, B., Prentice-Dunn, S., Jacobs, B., & Rogersok, R. W. (1982). General self-efficacy scale. APA PsycTests. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spielberger, C. D., Jacobs, G., Russell, S., & Crane, R. S. (1983). Assessment of anger: The state-trait anger scale. In Advances in personality assessment. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Tiedens, L. Z. (2001). Anger and advancement versus sadness and subjugation: The effect of negative emotion expressions on social status conferral. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 80(1), 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Umbra, R., & Fasbender, U. (2025). How to capture the rage? Development and validation of a state-trait anger scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 107(2), 188–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watson, D., & Clark, L. A. (1992). Affects separable and inseparable: On the hierarchical arrangement of the negative affects. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 62(3), 489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, D., & Clark, L. A. (1994). The PANAS-X: Manual for the positive and negative affect schedule-expanded form. University of Iowa. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Item | Factor 1 (Affective) | Factor 2 (Cognitive) | Factor 3 (Somatic/Behav.) |

|---|---|---|---|

| I get depressed easily. | 0.85 | 0.01 | 0.04 |

| I often feel sad in my daily life. | 0.71 | 0.08 | 0.12 |

| I often feel helplessness. | 0.58 | 0.26 | −0.03 |

| I often get dejected. | 0.51 | 0.28 | 0.04 |

| I feel unfortunate. | 0.49 | 0.29 | −0.02 |

| When things go off course, I feel it’s hard to set them right again on my own. | −0.01 | 0.78 | 0.06 |

| After a setback, I feel like I can’t cope. | 0.02 | 0.71 | 0.06 |

| I find it hard to snap out of it when I’m feeling sad. | 0.23 | 0.64 | 0.17 |

| I am saddened by the gap between how things are and how I want them to be. | 0.24 | 0.55 | 0.23 |

| Frustration makes me feel drained and want to quit. | 0.08 | 0.48 | 0.25 |

| When someone rejects me, I feel like crying. | −0.06 | 0.11 | 0.71 |

| I get a lump in my throat when I’m ignored. | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.71 |

| Sadness feels like a wrenching pain in my chest. | 0.03 | 0.13 | 0.69 |

| There are times when I get a sudden urge to cry. | 0.22 | −0.17 | 0.63 |

| When I’m sad, it feels hard to even move a finger. | 0.08 | 0.12 | 0.52 |

| DES Subscale | Joy | Interest | Sadness | Contempt | Surprise | Fear | Anger |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pearson r | −0.43 | −0.31 | 0.74 | 0.17 | 0.27 | 0.46 | 0.55 |

| Sig. | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.035 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Han, S. Cognitive Correlates of Emotional Dispositions: Differentiating Trait Sadness and Trait Anger via Attributional Style and Helplessness. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1401. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101401

Han S. Cognitive Correlates of Emotional Dispositions: Differentiating Trait Sadness and Trait Anger via Attributional Style and Helplessness. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(10):1401. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101401

Chicago/Turabian StyleHan, Seunghee. 2025. "Cognitive Correlates of Emotional Dispositions: Differentiating Trait Sadness and Trait Anger via Attributional Style and Helplessness" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 10: 1401. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101401

APA StyleHan, S. (2025). Cognitive Correlates of Emotional Dispositions: Differentiating Trait Sadness and Trait Anger via Attributional Style and Helplessness. Behavioral Sciences, 15(10), 1401. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101401