Are People More Averse of Their Peers Living in Hardship or Driving Luxury Cars? Individuals’ Willingness to Accept Their Peers’ Relative Circumstances

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Tri-Reference Point Theory Under Social Comparison

1.2. Peers’ Success Induces Stronger Relative Deprivation than Peers’ Suffering

1.3. Moderating Effects of Situational Competitiveness and Peers’ Effort Level

1.4. Overview of Studies

2. Experiment 1: Buy Lottery Tickets

2.1. Pilot Experiment

2.2. Participants and Design

2.3. Procedure

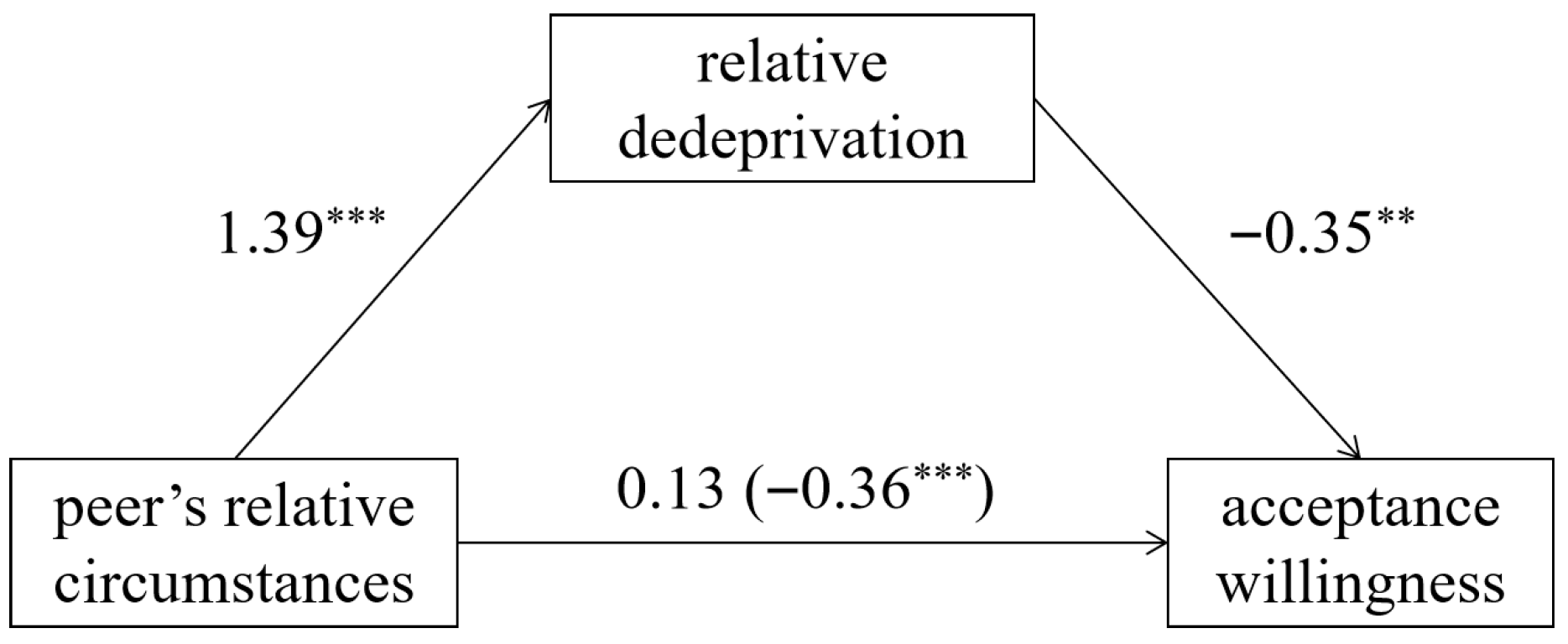

2.4. Results and Discussion

3. Experiment 2: Bonus Allocation

3.1. Participants and Design

3.2. Procedure

3.3. Results and Discussion

4. Experiment 3: The Moderating Effect of Situational Competitiveness

4.1. Participants and Design

4.2. Procedure

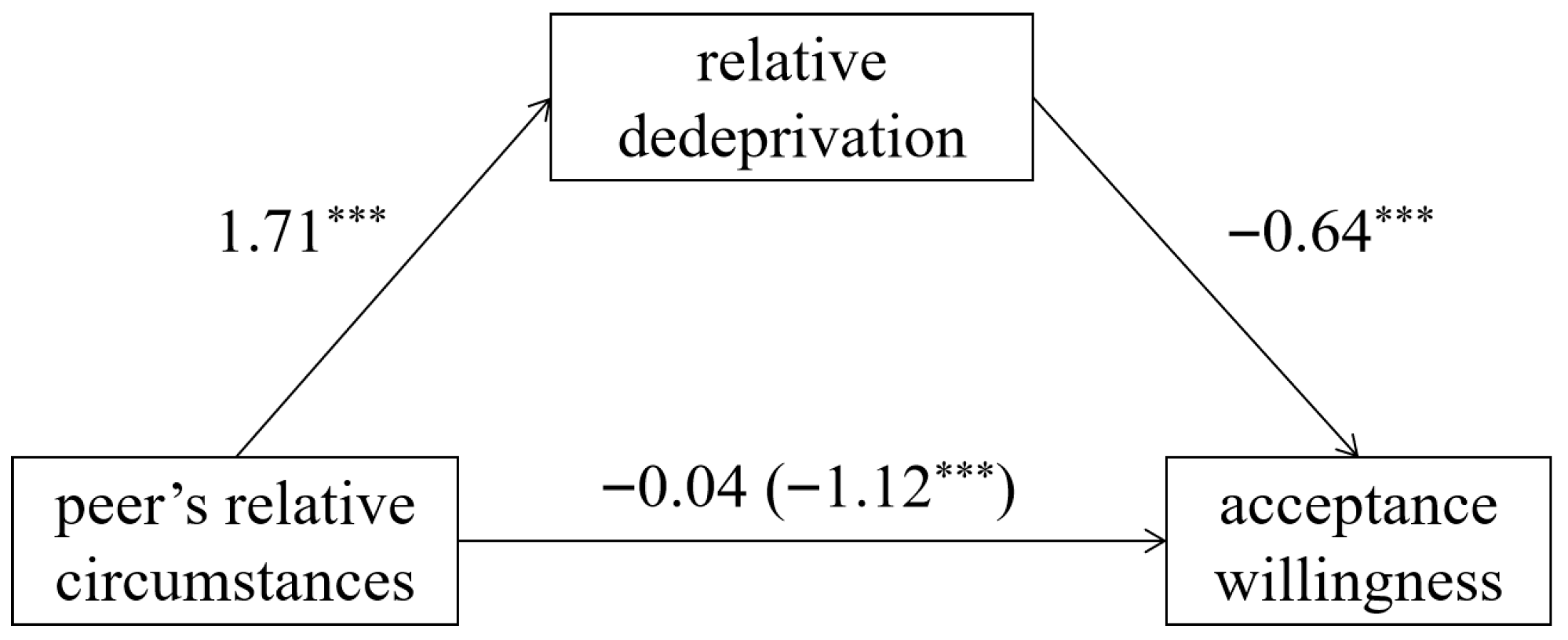

4.3. Results and Discussion

5. Experiment 4: The Moderating Effect of Peers’ Effort Levels

5.1. Participants and Design

5.2. Procedure

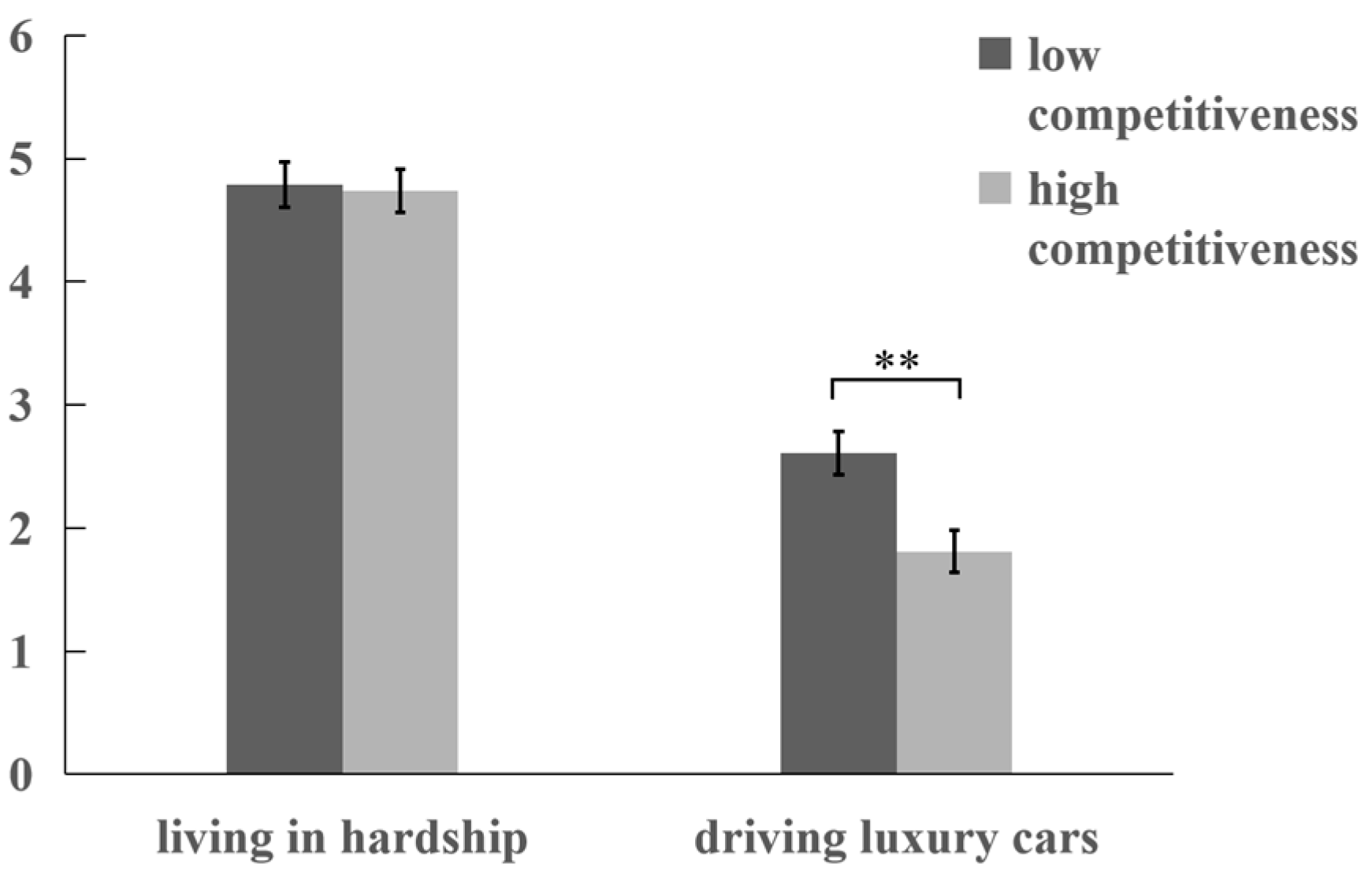

5.3. Results and Discussion

6. General Discussion

6.1. Research Implications

6.2. Limitations and Direction for Future Research

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adams, J. S. (1963). Towards an understanding of inequity. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 67(5), 422–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alicke, M. D., & Sedikides, C. (2009). Self-enhancement and self-protection: What they are and what they do. European Review of Social Psychology, 20(1), 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J., Yang, S. L., Xu, B. X., & Guo, Y. Y. (2021). How can successful people share their goodness with the world: The psychological mechanism underlying the upper social classes’ redistributive preferences and the role of humility. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 53(10), 1161–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, M., & Mussweiler, T. (2018). The culture of social comparison. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 115(39), E9067–E9074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batson, C. D., Duncan, B. D., Ackerman, P., Buckley, T., & Birch, K. (1981). Is empathic emotion a source of altruistic motivation? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 40(2), 290–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behler, A. M. C., Wall, C. S., Bos, A., & Green, J. D. (2020). To help or to harm? Assessing the impact of envy on prosocial and antisocial behaviors. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 46(7), 1156–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boecker, L., Loschelder, D. D., & Topolinski, S. (2022). How individuals react emotionally to others’ (mis) fortunes: A social comparison framework. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 123(1), 55–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caliskan, F., Idug, Y., Uvet, H., Gligor, N., & Kayaalp, A. (2024). Social comparison theory: A review and future directions. Psychology & Marketing, 41(11), 2823–2840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celniker, J. B., Gregory, A., Koo, H. J., Piff, P. K., Ditto, P. H., & Shariff, A. F. (2023). The moralization of effort. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 152(1), 60–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J., Burke, M., & de Gant, B. (2021). Country differences in social comparison on social media. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction, 4(CSCW3), 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, W., & He, Y. (2022). Cognition of opportunity inequality and residents’ happiness: An empirical study on family background, luck and personal effort. Journal of Guizhou University of Finance and Economics, 40(2), 79–88. [Google Scholar]

- Curry, O. S., Rowland, L. A., Van Lissa, C. J., Zlotowitz, S., McAlaney, J., & Whitehouse, H. (2018). Happy to help? A systematic review and meta-analysis of the effects of performing acts of kindness on the well-being of the actor. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 76, 320–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diel, K., Grelle, S., & Hofmann, W. (2021). A motivational framework of social comparison. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 120(6), 1415–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dwyer, R. J., Brady, W. J., Anderson, C., & Dunn, E. W. (2023). Are people generous when the financial stakes are high? Psychological Science, 34(9), 999–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ericsson, K. A., Krampe, R. T., & Tesch-Römer, C. (1993). The role of deliberate practice in the acquisition of expert performance. Psychological Review, 100(3), 363–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Festinger, L. (1954). A theory of social comparison processes. Human Relations, 7(2), 117–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foncelle, A., Barat, E., Dreher, J. C., & van Der Henst, J. B. (2022). Rank reversal aversion and fairness in hierarchies. Adaptive Human Behavior and Physiology, 8(4), 520–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsythe, R., Horowitz, J. L., Savin, N. E., & Sefton, M. (1994). Fairness in simple bargaining experiments. Games and Economic Behavior, 6(3), 347–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, S., & Dayan, K. (2004). Framing and risky choice as influenced by comparison of one’s achievements with others: The case of investment in the stock exchange. Journal of Business and Psychology, 18, 301–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J., Wang, P., Wang, X. T., Sun, Q., & Liu, Y. F. (2020). Effects of others’ reference points and psychological distance on self-other welfare tradeoff in gain and loss situations. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 52(5), 633–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, S. M., Tor, A., & Schiff, T. M. (2013). The psychology of competition: A social comparison perspective. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 8(6), 634–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Y. Y., Yang, S. L., & Hu, X. Y. (2017). Ideal balance versus realistic ladder: Social stratification and fairness researches based on psychological perspectives. Bulletin of Chinese Academy of Sciences, 32(2), 117–127. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A. F., & Preacher, K. J. (2013). Statistical mediation analysis with a multicategorical independent variable. British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology, 67(3), 451–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inzlicht, M., & Campbell, A. V. (2022). Effort feels meaningful. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 26(12), 1035–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica, 47, 263–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H., Callan, M. J., Gheorghiu, A. I., & Skylark, W. J. (2018). Social comparison processes in the experience of personal relative deprivation. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 48(9), 519–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J., & Qiu, T. (2021). The prisoner of comparison: What determines our choices and happiness. Beijing Normal University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Moyal, A., Motsenok, M., & Ritov, I. (2020). Arbitrary social comparison, malicious envy, and generosity. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 33(4), 444–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ongis, M., & Davidai, S. (2022). Personal relative deprivation and the belief that economic success is zero-sum. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 151(7), 1666–1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, C., Xin, Z. Y., Gao, D. D., & Xing, X. L. (2023). The effect of upward social comparison on intertemporal decision: The mediating role of relative deprivation. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 31(1), 189–193. [Google Scholar]

- Park, L. E., Naidu, E., Lemay, E. P., Canning, E. A., Ward, D. E., Panlilio, Z., & Vessels, V. (2023). Social evaluative threat across individual, relational, and collective selves. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 68, 139–222. [Google Scholar]

- Różycka-Tran, J., Boski, P., & Wojciszke, B. (2015). Belief in a zero-sum game as a social axiom: A 37-nation study. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 46(4), 525–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stapel, D. A., & Koomen, W. (2005). Competition, cooperation, and the effects of others on me. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 88(6), 1029–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D. Y., & Guo, Y. Y. (2016). Relative deprivation: Wanting, deserving, resentment for not having. Journal of Psychological Science, 39(3), 714–719. [Google Scholar]

- To, C., Kilduff, G. J., & Rosikiewicz, B. L. (2020). When interpersonal competition helps and when it harms: An integration via challenge and threat. Academy of Management Annals, 14(2), 908–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de Ven, N. (2016). Envy and its consequences: Why it is useful to distinguish between benign and malicious envy. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 10(6), 337–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, I., & Smith, H. J. (Eds.). (2002). Relative deprivation: Specification, development, and integration. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X. T., & Johnson, J. G. (2012). A tri-reference point theory of decision making under risk. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 141(4), 743–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X. T., & Wang, P. (2013). Tri-reference point theory of decision making: From principles to applications. Advances in Psychological Science, 21(8), 1331–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X. X., & Shen, Y. F. (2022). How to cope with the threat to moral self? The perspectives of memory bias in moral contexts. Advances in Psychological Science, 30(7), 1604–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J., Han, H. F., Zhang, C. Y., Sun, L. J., & Zhang, J. F. (2015). Reliability and validity of the marlowe-crowne social desirability scale in middle school students. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 23(4), 585–589. [Google Scholar]

- Wills, T. A. (1981). Downward comparison principles in social psychology. Psychological Bulletin, 90(2), 245–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B. P., & Zhang, L. (2012). Envy: A social emotion characterized by hostility. Advances in Psychological Science, 20(9), 1467–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, W., Ho, B., Meier, S., & Zhou, X. (2017). Rank reversal aversion inhibits redistribution across societies. Nature Human Behaviour, 1(8), 0142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, G. X., Li, A. M., & Wang, X. T. (2014). An analysis of wage gap and turnover decisions based on tri-reference point theory. Advances in Psychological Science, 22(9), 1363–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, M., & Ye, Y. D. (2016). The concept, measurement, influencing factors and effects of relative deprivation. Advances in Psychological Science, 24(3), 438–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yates, F. J., & Stone, E. R. (1992). The risk construct. In J. F. Yates (Ed.), Risk-taking behavior. Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Zagefka, H., Binder, J., Brown, R., & Hancock, L. (2013). Who is to blame? The relationship between ingroup identification and relative deprivation is moderated by ingroup attributions. Social Psychology, 44(6), 398–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H., Wei, L., Wang, J., & Zhang, W. (2024). Personal relative deprivation and moral self-judgments: The moderating role of sense of control. Journal of Research in Personality, 111, 104509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L., Ye, J., Wu, X., & Hu, F. (2018). The influence of the tri-reference points on fairness and satisfaction perception. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Competitiveness | Effect | SE | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| low | −1.38 | 0.21 | [−1.77, −0.99] |

| high | −2.41 | 0.27 | [−2.91, −1.85] |

| Effort Level | Effect | SE | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| control | −2.27 | 0.30 | [−2.87, −1.69] |

| high | −1.42 | 0.23 | [−1.89, −0.97] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hu, X.; Liu, J.; Sun, F.; Wang, X. Are People More Averse of Their Peers Living in Hardship or Driving Luxury Cars? Individuals’ Willingness to Accept Their Peers’ Relative Circumstances. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1395. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101395

Hu X, Liu J, Sun F, Wang X. Are People More Averse of Their Peers Living in Hardship or Driving Luxury Cars? Individuals’ Willingness to Accept Their Peers’ Relative Circumstances. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(10):1395. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101395

Chicago/Turabian StyleHu, Xiaohan, Jie Liu, Fengyang Sun, and Xiuxin Wang. 2025. "Are People More Averse of Their Peers Living in Hardship or Driving Luxury Cars? Individuals’ Willingness to Accept Their Peers’ Relative Circumstances" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 10: 1395. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101395

APA StyleHu, X., Liu, J., Sun, F., & Wang, X. (2025). Are People More Averse of Their Peers Living in Hardship or Driving Luxury Cars? Individuals’ Willingness to Accept Their Peers’ Relative Circumstances. Behavioral Sciences, 15(10), 1395. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101395