Do the Four Components of Psychological Capital Have Differential Buffering Effects? A Longitudinal Study on Parental Neglect and Adolescent Problematic Short-Form Video Use

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Parental Neglect and Problematic Short-Form Video Use

1.2. Protective Role of Psychological Capital

1.3. The Present Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measurements

2.2.1. Parental Neglect

2.2.2. Problematic Short-Form Video Use

2.2.3. Psychological Capital

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary Analysis

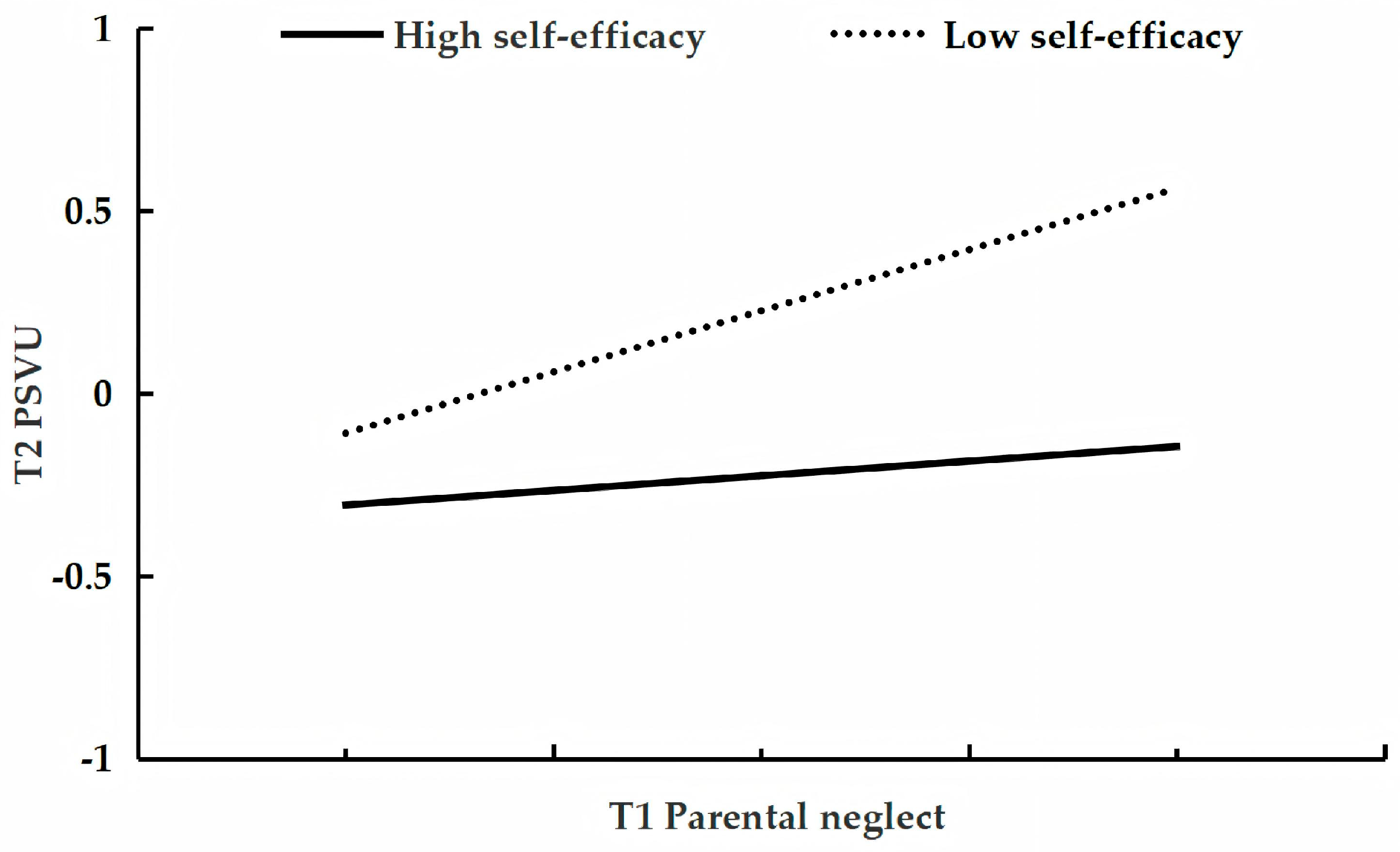

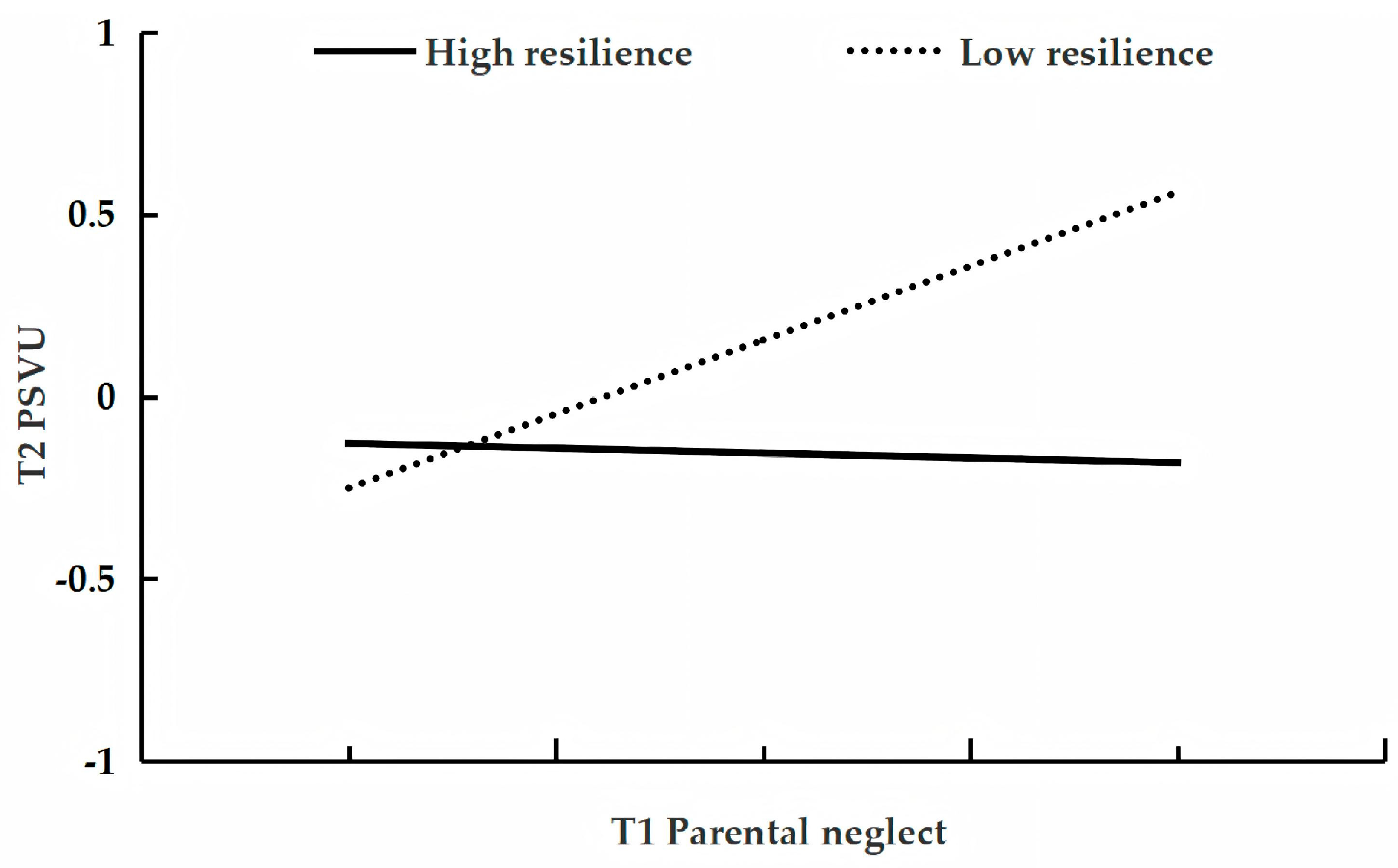

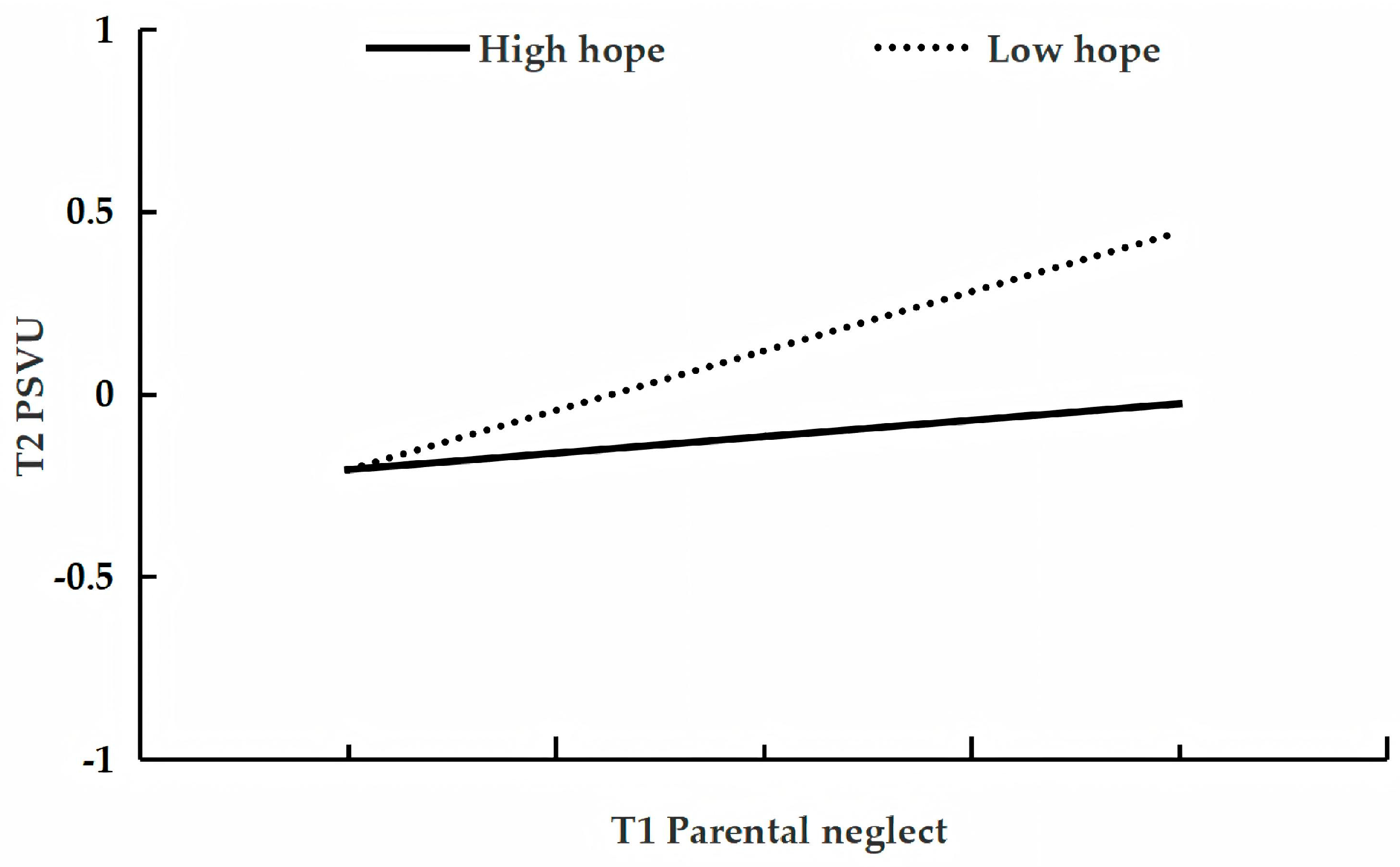

3.2. Moderating Effect Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Allin, H., Wathen, C. N., & MacMillan, H. (2005). Treatment of child neglect: A systematic review. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 50(8), 497–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, K. M. (2018). Post-traumatic growth and resilience despite experiencing trauma and oppression. Journal of Family Social Work, 21(1), 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aspinwall, L. G., & Leaf, S. L. (2002). In search of the unique aspects of hope: Pinning our hopes on positive emotions, future-oriented thinking, hard times, and other people. Psychological Inquiry, 13(4), 276–288. [Google Scholar]

- Ayhan, A. B., & Beyazit, U. (2021). The associations between loneliness and self-esteem in children and neglectful behaviors of their parents. Child Indicators Research, 14(5), 1863–1879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (1978). Reflections on self-efficacy. Advances in Behaviour Research and Therapy, 1(4), 237–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyazit, U., Yurdakul, Y., & Ayhan, A. B. (2024). The mediating role of trait emotional intelligence in the relationship between parental neglect and cognitive emotion regulation strategies. BMC Psychology, 12(1), 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bi, X., & Jin, J. (2021). Psychological capital, college adaptation, and internet addiction: An analysis based on moderated mediation model. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, 712964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bifulco, A., Kwon, J., Jacobs, C., Moran, P. M., Bunn, A., & Beer, N. (2006). Adult attachment style as mediator between childhood neglect/abuse and adult depression and anxiety. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 41(10), 796–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blum, R. W., McNeely, C., & Nonnemaker, J. (2002). Vulnerability, risk, and protection. Journal of Adolescent Health, 31(1), 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bruininks, P., & Malle, B. F. (2005). Distinguishing hope from optimism and related affective states. Motivation and Emotion, 29(4), 324–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, M., Lei, J., He, R., Jiang, Y., & Yang, H. (2023). TikTok use and psychosocial factors among adolescents: Comparisons of non-users, moderate users, and addictive users. Psychiatry Research, 325, 115247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y., Li, M., Guo, F., & Wang, X. (2023). The effect of short-form video addiction on users’ attention. Behaviour & Information Technology, 42(16), 2893–2910. [Google Scholar]

- Chidambaram, V., Shanmugam, K., & Parayitam, S. (2023). Parental neglect and emotional wellbeing among adolescent students from India: Social network addiction as a mediator and gender as a moderator. Behaviour & Information Technology, 42(7), 869–887. [Google Scholar]

- Christ, S. L., Kwak, Y. Y., & Lu, T. (2017). The joint impact of parental psychological neglect and peer isolation on adolescents’ depression. Child Abuse & Neglect, 69, 151–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. R., Menon, S. V., Shorey, R. C., Le, V. D., & Temple, J. R. (2017). The distal consequences of physical and emotional neglect in emerging adults: A person-centered, multi-wave, longitudinal study. Child Abuse & Neglect, 63, 151–161. [Google Scholar]

- David, M. E., & Roberts, J. A. (2024). TikTok brain: An investigation of short-form video use, self-control, and phubbing. Social Science Computer Review. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteves, M., Scoloveno, R. L., Mahat, G., Yarcheski, A., & Scoloveno, M. A. (2013). An integrative review of adolescent hope. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 28(2), 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fergus, S., & Zimmerman, M. A. (2005). Adolescent resilience: A framework for understanding healthy development in the face of risk. Annual Review of Public Health, 26(1), 399–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finch, J., Farrell, L. J., & Waters, A. M. (2020). Searching for the HERO in youth: Does psychological capital (PsyCap) predict mental health symptoms and subjective wellbeing in Australian school-aged children and adolescents? Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 51(6), 1025–1036. [Google Scholar]

- Franco, G. D. R., & Rodrigues, M. C. (2018). Self-efficacy and positive youth development: A narrative review of the literature. Trends in Psychology, 26, 2267–2282. [Google Scholar]

- Gan, X., Qin, K. N., Xiang, G. X., & Jin, X. (2023). The relationship between parental neglect and cyberbullying perpetration among Chinese adolescent: The sequential role of cyberbullying victimization and internet gaming disorder. Frontiers in Public Health, 11, 1128123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glickman, E. A., Choi, K. W., Lussier, A. A., Smith, B. J., & Dunn, E. C. (2021). Childhood emotional neglect and adolescent depression: Assessing the protective role of peer social support in a longitudinal birth cohort. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, 681176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gujar, N. M., & Ali, A. (2019). Effects of psychological capital and self-esteem on emotional and behavioral problems among adolescents. Journal of Mental Health and Human Behaviour, 24(2), 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatkevich, C., Sumlin, E., & Sharp, C. (2021). Examining associations between child abuse and neglect experiences with emotion regulation difficulties indicative of adolescent suicidal ideation risk. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, 630697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Herrman, H., Stewart, D. E., Diaz-Granados, N., Berger, E. L., Jackson, B., & Yuen, T. (2011). What is resilience? The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 56(5), 258–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, M., & Schermer, J. A. (2024). Childhood neglect and loneliness: The unique roles of parental figure and child sex. Behavioral Sciences, 14(6), 442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahantigh, H., Nikmanesh, Z., & Noori Moghadam, S. (2024). Effectiveness of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy on resilience and academic motivation. Research Strategies in Educational Sciences, 1(1), 15–26. [Google Scholar]

- Jameel, S. N., Shah, S. A., & Zahoor, S. Z. (2018). Perceived stress and parental neglect as determinants of internet addiction among adolescents. International Journal of Research in Social Sciences & Humanities, 6, 628–637. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, R. L., & Vazsonyi, A. T. (2024). Childhood neglect, low self-control, and violence victimization in the Czech Republic and the United States: A cross-cultural comparison. International Criminology, 4(3), 231–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karacic, S., & Oreskovic, S. (2017). Internet addiction through the phase of adolescence: A questionnaire study. JMIR Mental Health, 4(2), e5537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kealy, D., Laverdiere, O., Cox, D. W., & Hewitt, P. L. (2023). Childhood emotional neglect and depressive and anxiety symptoms among mental health outpatients: The mediating roles of narcissistic vulnerability and shame. Journal of Mental Health, 32(1), 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J., & Kim, H. (2024, May 11–16). Unlocking creator-AI synergy: Challenges, requirements, and design opportunities in AI-powered short-form video production. 2024 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 1–23), Honolulu, HI, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Kuss, D. J., Van Rooij, A. J., Shorter, G. W., Griffiths, M. D., & van de Mheen, D. (2013). Internet addiction in adolescents: Prevalence and risk factors. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(5), 1987–1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwak, J. Y., Kim, J. Y., & Yoon, Y. W. (2018). Effect of parental neglect on smartphone addiction in adolescents in South Korea. Child Abuse & Neglect, 77, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwok, S. Y., & Gu, M. (2019). Childhood neglect and adolescent suicidal ideation: A moderated mediation model of hope and depression. Prevention Science, 20(5), 632–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F., Wang, G., Zhu, D., Liu, S., Liao, J., Zhang, S., & Li, J. (2023). Parental neglect and short-form video application addiction in Chinese adolescents: The mediating role of alexithymia and the moderating role of refusal self-efficacy. Child Abuse & Neglect, 143, 106345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y., & Zhu, D. (2024). The relationship between negotiable fate and life satisfaction: The serial mediation by self-esteem and positive psychological capital. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 17, 1625–1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q., Ouyang, L., Fan, L., Liao, A., Li, Z., Chen, X., Yuan, L., & He, Y. (2024). Association between childhood trauma and Internet gaming disorder: A moderated mediation analysis with depression as a mediator and psychological resilience as a moderator. BMC Psychiatry, 24(1), 412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q. Q., Tu, W., Shang, Y. F., & Xu, X. P. (2022a). Unique and interactive effects of parental neglect, school connectedness, and trait self-control on mobile short-form video dependence among Chinese left-behind adolescents. Child Abuse & Neglect, 134, 105939. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Q. Q., Xu, X. P., Yang, X. J., Xiong, J., & Hu, Y. T. (2022b). Distinguishing different types of mobile phone addiction: Development and validation of the Mobile Phone Addiction Type Scale (MPATS) in adolescents and young adults. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(5), 2593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., Gao, Q., & Ma, L. (2021). Taking micro-breaks at work: Effects of watching funny short-form videos on subjective experience, physiological stress, and task performance. In International conference on human-computer interaction (pp. 183–200). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Luthans, F., Avey, J. B., & Patera, J. L. (2008). Experimental analysis of a web-based training intervention to develop positive psychological capital. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 7(2), 209–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthans, F., Youssef, C. M., & Avolio, B. J. (2007). Psychological capital. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Luthans, F., & Youssef-Morgan, C. M. (2017). Psychological capital: An evidence-based positive approach. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 4(1), 339–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H., & Chen, L. (2022). Time management disposition mediates the influence of childhood psychological maltreatment on undergraduates’ procrastination. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 15, 1489–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Massullo, C., De Rossi, E., Carbone, G. A., Imperatori, C., Ardito, R. B., Adenzato, M., & Farina, B. (2023). Child maltreatment, abuse, and neglect: An umbrella review of their prevalence and definitions. Clinical Neuropsychiatry, 20(2), 72–99. [Google Scholar]

- Masten, A. S., & Reed, M. G. J. (2002). Resilience in development. Handbook of Positive Psychology, 74(2), 74–88. [Google Scholar]

- Maughan, D., & Moore, S. C. (2010). Dimensions of child neglect: An exploration of parental neglect and its relationship with delinquency. Child Welfare, 89(4), 47–65. [Google Scholar]

- Okuzono, S. S., Shiba, K., Lee, H. H., Shirai, K., Koga, H. K., Kondo, N., Fujiwara, T., Kondo, K., Grodstein, F., Kubzansky, L. D., & Trudel-Fitzgerald, C. (2022). Optimism and longevity among Japanese older adults. Journal of Happiness Studies, 23(6), 2581–2595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Proctor, L. J., & Dubowitz, H. (2014). Child neglect: Challenges and controversies. In J. E. Korbin, & R. D. Krugman (Eds.), Handbook of child maltreatment (pp. 27–61). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rincon Uribe, F. A., Neira Espejo, C. A., & Pedroso, J. D. S. (2022). The role of optimism in adolescent mental health: A systematic review. Journal of Happiness Studies, 23(2), 815–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarman, A., & Tuncay, S. (2023). The relationship of Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, TikTok and WhatsApp/Telegram with loneliness and anger of adolescents living in Turkey: A structural equality model. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 72, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheier, M. F., & Carver, C. S. (1985). Optimism, coping, and health: Assessment and implications of generalized outcome expectancies. Health Psychology, 4(3), 219–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schunk, F., Zeh, F., & Trommsdorff, G. (2022). Cybervictimization and well-being among adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic: The mediating roles of emotional self-efficacy and emotion regulation. Computers in Human Behavior, 126, 107035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Segerstrom, S. C. (2005). Optimism and immunity: Do positive thoughts always lead to positive effects? Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 19(3), 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, X., Xie, X., & Wu, S. (2023). Do adolescents addict to internet games after being phubbed by parents? The roles of maladaptive cognition and self-esteem. Current Psychology, 42(3), 2255–2267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, C. R. (1994). The psychology of hope: You can get there from here. Simon and Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Snyder, C. R. (2002). Hope theory: Rainbows in the mind. Psychological Inquiry, 13(4), 249–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soffer, N., Gilboa–Schechtman, E., & Shahar, G. (2008). The relationship of childhood emotional abuse and neglect to depressive vulnerability and low self–efficacy. International Journal of Cognitive Therapy, 1(2), 151–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C., Ge, S., & Zhang, W. (2025). The impact of parental psychological control on adolescents’ physical activity: The mediating role of self-control and the moderating role of psychological capital. Frontiers in Psychology, 16, 1501720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, R., & Song, L. (2021). The dampen effect of psychological capital on adolescent depression: A moderated mediation model. Current Psychology, 40(1), 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparks, L. A., Trentacosta, C. J., Hicks, M. R., Kernsmith, P., & Smith-Darden, J. (2021). Hope as a protective factor: Relations to adverse childhood experiences, delinquency, and posttraumatic stress symptoms. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 30(12), 3005–3015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoltenborgh, M., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., & Van Ijzendoorn, M. H. (2013). The neglect of child neglect: A meta-analytic review of the prevalence of neglect. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 48(3), 345–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straus, M. A., Hamby, S. L., Finkelhor, D., Moore, D. W., & Runyan, D. (1998). Identification of child maltreatment with the parent-child conflict tactics scales: Development and psychometric data for a national sample of American parents. Child Abuse & Neglect, 22(4), 249–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Z., Ding, W., Li, J., Jiang, M., Li, W., & Xie, R. (2024). Why am I always lonely? The lasting impact of childhood harsh parental discipline on adolescents’ loneliness. Family Relations, 73(3), 1933–1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S. H., & Chen, Y. A. (2024). The lonely algorithm problem: The relationship between algorithmic personalization and social connectedness on TikTok. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 29(5), zmae017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H., & Lei, L. (2022). The relationship between parental phubbing and short-form videos addiction among Chinese adolescents. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 32(4), 1580–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W., Mehmood, A., Li, P., Yang, Z., Niu, J., Chu, H., Qiao, Z., Qiu, X., Zhou, J., Yang, Y., & Yang, X. (2021). Perceived stress and smartphone addiction in medical college students: The mediating role of negative emotions and the moderating role of psychological capital. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 660234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q., Luo, J., Bai, J., Hou, M., & Li, X. (2019). Effect of security on mobile addiction: Mediating role of actual social avoidance. Psychological Development and Education, 35(5), 589–596. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, L., Sun, L., Lei, Z., & Fu, B. (2025). How do features in health short-form videos impact viewer engagement: An empirical study. Industrial Management & Data Systems. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J., Xu, X., Zhang, Y., Tan, Y., Wu, D., Shi, M., & Huang, H. (2023). The effect of short-form video addiction on undergraduates’ academic procrastination: A moderated mediation model. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1298361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, X., Guo, Q., & Wang, P. (2021). Childhood parental neglect and adolescent internet gaming disorder: From the perspective of a distal—Proximal—Process—Outcome model. Children and Youth Services Review, 120, 105564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y., Chai, X., Zheng, W., Wang, M., Feng, X., Heng, C., Du, J., & Zhang, Q. (2024). The effect of neuroticism on mobile phone addiction among undergraduate nursing students: A moderated mediation model. BMC Psychiatry, 24(1), 810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z., Zhu, X., & Li, Y. (2024). The association between problematic short video use and suicidal ideation and self-injurious behaviors: The mediating roles of sleep disturbance and depression. BMC Public Health, 24(1), 1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C., & Zhu, B. (2025). Digital gratification: Short video consumption and mental health in rural China. Frontiers in Public Health, 13, 1536191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J. Y., Ji, X. Z., Fan, Y. N., & Cui, Y. X. (2022). Emotion management for college students: Effectiveness of a mindfulness-based emotion management intervention on emotional regulation and resilience of college students. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 210(9), 716–722. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J. Y., Zhang, H., Chen, Y. B., Zhang, L. H., Zhou, Y. Q., & Yang, L. (2025). Parental neglect and social media addiction of adolescents: The chain mediation effect of basic psychological need and personal growth initiative. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 81, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K., Zhang, Y., & Dong, Y. H. (2010). Positive psychological capital: Measurement and relationship with mental health. Studies of Psychology & Behavior, 8(1), 58–64. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z., Dang, J., Li, J., He, Y., Huang, S., Wang, Y., & Yang, X. (2021). Childhood trauma and self-control: The mediating role of depletion sensitivity. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 30(6), 1599–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C., Jiang, Y., Lei, H., Wang, H., & Zhang, C. (2024). The relationship between short-form video use and depression among Chinese adolescents: Examining the mediating roles of need gratification and short-form video addiction. Heliyon, 10(9), e30346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristics | Categories | Number (Percentage) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 349 (52.5%) |

| Female | 316 (47.5%) | |

| Age | 12 years old | 221 (33.2%) |

| 13 years old | 188 (28.3%) | |

| 14 years old | 166 (25.0%) | |

| 15 years old | 90 (13.5%) | |

| Grade | Seventh grade | 266 (40.0%) |

| Eighth grade | 218 (32.8%) | |

| Ninth grade | 181 (27.2%) | |

| Maternal education level | Junior high school or below | 190 (28.6%) |

| Senior high school or vocational school | 172 (25.9%) | |

| College (associate or bachelor’s degree) | 187 (28.1%) | |

| Master’s degree or above | 116 (17.4%) | |

| Paternal education level | Junior high school or below | 164 (24.7%) |

| Senior high school or vocational school | 170 (25.6%) | |

| College (associate or bachelor’s degree) | 214 (32.2%) | |

| Master’s degree or above | 117 (17.6%) | |

| Maternal work status | Unemployed | 72 (10.8%) |

| Part-time employed | 71 (10.7%) | |

| Full-time employed | 522 (78.5%) | |

| Paternal work status | Unemployed | 51 (7.7%) |

| Part-time employed | 94 (14.1%) | |

| Full-time employed | 520 (78.2%) | |

| Family socioeconomic status | Very low | 131 (20.3%) |

| Relatively low | 181 (27.2%) | |

| Medium | 215 (32.3%) | |

| Relatively high | 69 (10.4%) | |

| Very high | 65 (9.8%) | |

| Only child | Yes | 410 (61.7%) |

| No | 255 (38.3%) |

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. T1 Parental neglect | — | ||||||

| 2. T1 Self-efficacy | −0.25 *** | — | |||||

| 3. T1 Resilience | −0.34 *** | 0.55 *** | — | ||||

| 4. T1 Hope | −0.24 *** | 0.54 *** | 0.55 *** | — | |||

| 5. T1 Optimism | −0.17 *** | 0.56 *** | 0.53 *** | 0.52 *** | — | ||

| 6. T1 PSVU | 0.46 *** | −0.29 *** | −0.34 *** | −0.20 *** | −0.18 *** | — | |

| 7. T2 PSVU | 0.50 *** | −0.36 *** | −0.37 *** | −0.26 *** | −0.24 *** | 0.60 *** | — |

| Mean | 5.02 | 32.02 | 34.10 | 29.37 | 28.17 | 13.13 | 14.64 |

| SD | 3.61 | 9.88 | 9.86 | 7.81 | 7.63 | 6.76 | 7.84 |

| Regression Equation | Significance of Coefficients | Bootstrap | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome Variable | Independent Variables | β | SE | t | p | LLCI | ULCI |

| T2 PSVU | Gender | −0.06 | 0.06 | −1.02 | 0.31 | −0.17 | 0.05 |

| Age | −0.08 ** | 0.03 | −2.75 | <0.01 | −0.14 | −0.02 | |

| Maternal education level | −0.21 | 0.03 | 6.20 | <0.001 | −0.27 | −0.14 | |

| Paternal education level | 0.14 | 0.03 | 4.33 | <0.001 | 0.08 | 0.21 | |

| Maternal work status | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.88 | 0.38 | −0.03 | 0.09 | |

| Paternal work status | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.39 | 0.70 | −0.06 | 0.08 | |

| Family socioeconomic status | 0.05 | 0.03 | 1.92 | 0.06 | −0.01 | 0.10 | |

| Only child | −0.02 | 0.06 | −0.28 | 0.78 | −0.14 | 0.11 | |

| T1 PSVU | 0.39 *** | 0.04 | 9.97 | <0.001 | 0.31 | 0.46 | |

| T1 Parental neglect | 0.23 *** | 0.04 | 6.08 | <0.001 | 0.15 | 0.30 | |

| T1 Self-efficacy | −0.16 *** | 0.03 | −4.59 | <0.001 | −0.23 | −0.09 | |

| T1 Parental neglect × T1 Self-efficacy | −0.10 *** | 0.03 | −3.47 | <0.001 | −0.16 | −0.05 | |

| Regression Equation | Significance of Coefficients | Bootstrap | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome Variable | Independent Variables | β | SE | t | p | LLCI | ULCI |

| T2 PSVU | Gender | −0.08 | 0.06 | −1.40 | 0.16 | −0.19 | 0.03 |

| Age | −0.08 ** | 0.03 | −2.86 | <0.01 | −0.14 | −0.03 | |

| Maternal education level | −0.21 *** | 0.03 | −6.28 | <0.001 | −0.27 | −0.14 | |

| Paternal education level | 0.15 *** | 0.03 | 4.76 | <0.001 | 0.09 | 0.22 | |

| Maternal work status | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.73 | 0.47 | −0.04 | 0.08 | |

| Paternal work status | 0.04 | 0.03 | 1.05 | 0.29 | −0.03 | 0.10 | |

| Family socioeconomic status | 0.05 * | 0.03 | 2.16 | <0.05 | 0.01 | 0.10 | |

| Only child | −0.02 | 0.06 | −0.35 | 0.73 | −0.15 | 0.10 | |

| T1 PSVU | 0.36 *** | 0.04 | 9.20 | <0.001 | 0.28 | 0.43 | |

| T1 Parental neglect | 0.21 *** | 0.04 | 5.77 | <0.001 | 0.14 | 0.28 | |

| T1 Resilience | −0.11 ** | 0.03 | −3.32 | <0.01 | −0.18 | −0.05 | |

| T1 Parental neglect × T1 Resilience | −0.17 *** | 0.03 | −5.97 | <0.001 | −0.22 | −0.11 | |

| Regression Equation | Significance of Coefficients | Bootstrap | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome Variable | Independent Variables | β | SE | t | p | LLCI | ULCI |

| T2 PSVU | Gender | −0.07 | 0.06 | −1.21 | 0.23 | −0.18 | 0.04 |

| Age | −0.07 * | 0.03 | −2.47 | <0.05 | −0.13 | −0.02 | |

| Maternal education level | −0.22 *** | 0.03 | −6.55 | <0.001 | −0.28 | −0.15 | |

| Paternal education level | 0.16 *** | 0.03 | 4.74 | <0.001 | 0.09 | 0.22 | |

| Maternal work status | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.82 | 0.41 | −0.03 | 0.08 | |

| Paternal work status | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.57 | 0.57 | −0.05 | 0.09 | |

| Family socioeconomic status | 0.05 | 0.03 | 1.82 | 0.07 | −0.01 | 0.10 | |

| Only child | −0.02 | 0.06 | −0.29 | 0.77 | −0.15 | 0.11 | |

| T1 PSVU | 0.42 *** | 0.04 | 11.21 | <0.001 | 0.35 | 0.49 | |

| T1 Parental neglect | 0.23 *** | 0.04 | 6.03 | <0.001 | 0.15 | 0.30 | |

| T1 Hope | −0.09 ** | 0.03 | −2.74 | <0.01 | −0.15 | −0.02 | |

| T1 Parental neglect × T1 Hope | −0.10 *** | 0.03 | −3.94 | <0.001 | −0.16 | −0.05 | |

| Regression Equation | Significance of Coefficients | Bootstrap | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome Variable | Independent Variables | β | SE | t | p | LLCI | ULCI |

| T2 PSVU | Gender | −0.06 | 0.06 | −1.04 | 0.30 | −0.17 | 0.05 |

| Age | −0.07 * | 0.03 | −2.50 | <0.05 | −0.13 | −0.02 | |

| Maternal education level | −0.21 | 0.03 | −6.16 | <0.001 | −0.28 | −0.14 | |

| Paternal education level | 0.15 | 0.03 | 4.37 | <0.001 | 0.08 | 0.22 | |

| Maternal work status | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.56 | 0.57 | −0.04 | 0.08 | |

| Paternal work status | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.56 | 0.57 | −0.05 | 0.09 | |

| Family socioeconomic status | 0.04 | 0.03 | 1.38 | 0.17 | −0.02 | 0.09 | |

| Only child | −0.02 | 0.06 | −0.34 | 0.74 | −0.15 | 0.11 | |

| T1 PSVU | 0.42 *** | 0.04 | 11.01 | <0.001 | 0.35 | 0.50 | |

| T1 Parental neglect | 0.25 *** | 0.04 | 6.56 | <0.001 | 0.18 | 0.33 | |

| T1 Optimism | −0.10 ** | 0.04 | −2.76 | <0.01 | −0.17 | −0.03 | |

| T1 Parental neglect × T1 Optimism | −0.05 | 0.03 | −1.68 | 0.09 | −0.12 | 0.01 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

An, L.; Xu, X.; Li, H.; Liu, Q. Do the Four Components of Psychological Capital Have Differential Buffering Effects? A Longitudinal Study on Parental Neglect and Adolescent Problematic Short-Form Video Use. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1396. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101396

An L, Xu X, Li H, Liu Q. Do the Four Components of Psychological Capital Have Differential Buffering Effects? A Longitudinal Study on Parental Neglect and Adolescent Problematic Short-Form Video Use. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(10):1396. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101396

Chicago/Turabian StyleAn, Lianpeng, Xiaopan Xu, Hongwei Li, and Qingqi Liu. 2025. "Do the Four Components of Psychological Capital Have Differential Buffering Effects? A Longitudinal Study on Parental Neglect and Adolescent Problematic Short-Form Video Use" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 10: 1396. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101396

APA StyleAn, L., Xu, X., Li, H., & Liu, Q. (2025). Do the Four Components of Psychological Capital Have Differential Buffering Effects? A Longitudinal Study on Parental Neglect and Adolescent Problematic Short-Form Video Use. Behavioral Sciences, 15(10), 1396. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101396