Diverging Paths to the Self: The Distinct Psychological Roles of Nostalgia and Declinism in Personal Growth

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Nostalgia

1.2. Declinism

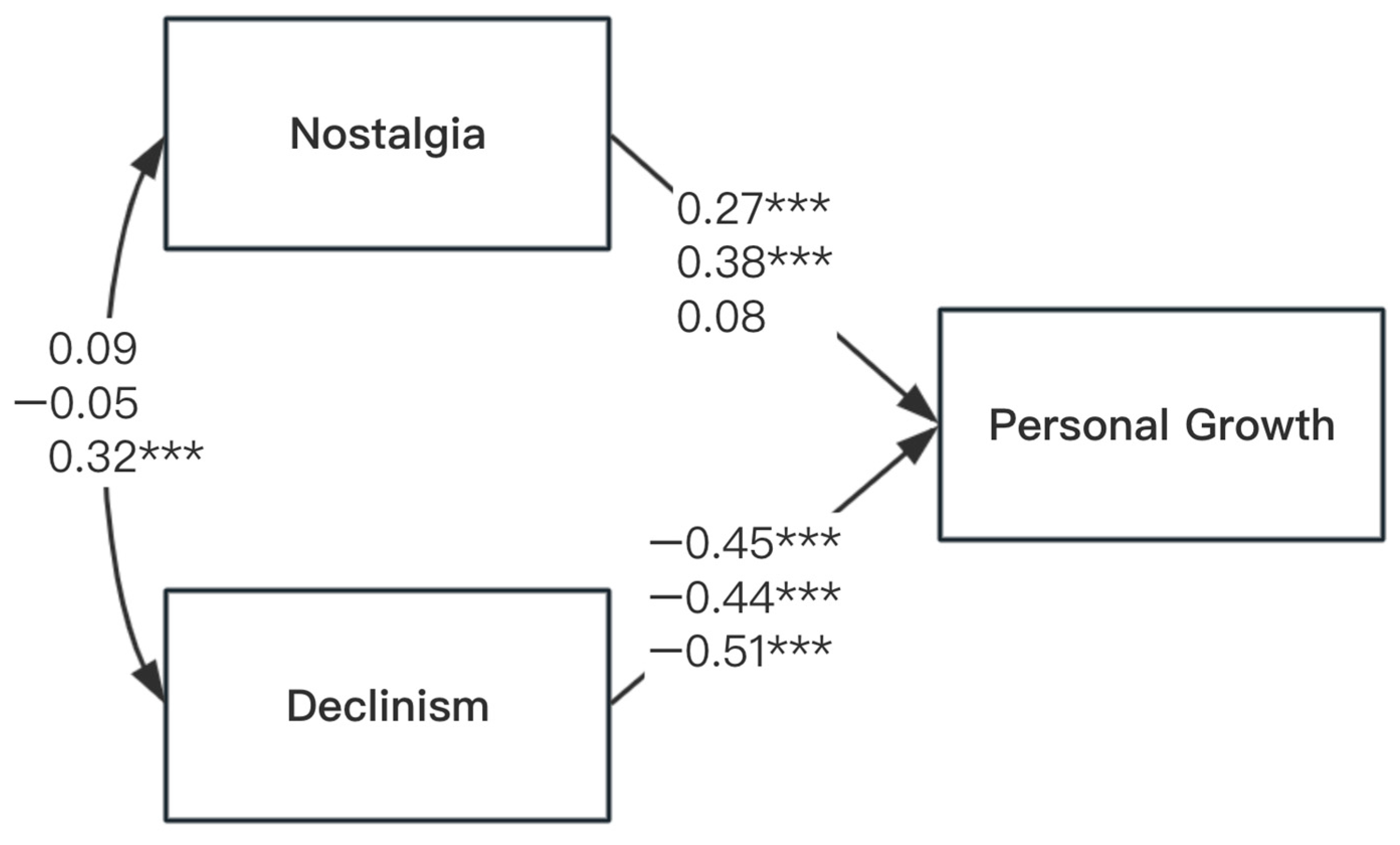

1.3. Divergent Relations of Nostalgia and Declinism with Personal Growth: A Confirmatory Approach

1.4. Differentiating Among Nostalgia Measures: An Exploratory Approach

1.5. Overview

2. Study 1

2.1. Method

2.1.1. Participants and Design

2.1.2. Procedure and Measures

2.2. Results and Discussion

2.2.1. Associations Among Variables

2.2.2. Distinct Effects of Nostalgia and Declinism on Personal Growth Across Conditions

2.3. Summary

3. Study 2

3.1. Method

3.1.1. Participants and Design

3.1.2. Procedure and Materials

3.2. Results

3.2.1. Manipulation Check

3.2.2. Effects of Nostalgia and Declinism on Personal Growth

4. General Discussion

4.1. Implications

4.2. Limitations and Future Directions

4.3. Concluding Remarks

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abeyta, A. A., Routledge, C., Roylance, C., Wildschut, R. T., & Sedikides, C. (2015). Attachment-related avoidance and the social and agentic content of nostalgic memories. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 32(3), 406–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrams, M. H. (1988). A glossary of literary terms (5th ed.). Holt, Rinehart and Winston, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin, M., & Landau, M. J. (2014). Exploring nostalgia’s influence on psychological growth. Self and Identity, 13(2), 162–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batcho, K. I. (1995). Nostalgia: A psychological perspective. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 80(1), 131–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batcho, K. I. (2013). Nostalgia: Retreat or support in difficult times? American Journal of Psychology, 126(3), 355–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, J. J., & McAdams, D. P. (2004). Personal growth in adults’ stories of life transitions. Journal of Personality, 72(3), 573–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandtstädter, J., Wentura, D., & Rothermund, K. (1999). Intentional self development through adulthood and later life: Tenacious pursuit and flexible adjustment of goals. In J. Brandtstadter, & R. M. Lerner (Eds.), Action and self-development: Theory and research through the life span (pp. 373–400). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Carver, C. S., & White, T. L. (1994). Behavioral inhibition, behavioral activation, and affective responses to impending reward and punishment: The BIS/BAS Scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67(2), 319–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H. B., Yeh, S. S., & Huan, T. C. (2014). Nostalgic emotion, experiential value, brand image, and consumption intentions of customers of nostalgic-themed restaurants. Journal of Business Research, 67(3), 354–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, W. Y., Sedikides, C., & Wildschut, T. (2016). Induced nostalgia increases optimism (via social connectedness and self-esteem) among individuals high, but not low, in trait nostalgia. Personality and Individual Differences, 90, 283–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, W. Y., Wildschut, T., Sedikides, C., Hepper, E. G., Arndt, J., & Vingerhoets, A. J. J. M. (2013). Back to the future: Nostalgia increases optimism. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 39(11), 1484–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins English Dictionary. (2023). Collins English Dictionary (14th ed.). Collins. [Google Scholar]

- Dang, J., Sedikides, C., Wildschut, T., & Liu, L. (2024). More than a barrier: Nostalgia inhibits, but also promotes, favorable responses to innovative technology. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 126(6), 998–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, J., Sedikides, C., Wildschut, T., & Liu, L. (2025). Nostalgia encourages exploration and fosters uncertainty in response to AI technology. British Journal of Social Psychology, 64, e12843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. Plenum. [Google Scholar]

- de Freitas, C. P. P., Damásio, B. F., Tobo, P. R., Kamei, H. H., & Koller, S. H. (2016). Systematic review about personal growth initiative. Anales de Psicología, 32(3), 770–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliot, A. J. (2006). The hierarchical model of approach-avoidance motivation. Motivation and Emotion, 30(2), 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, J. A., & McNaughton, N. (2000). The neuropsychology of anxiety: An enquiry into the functions of the septo-hippocampal system. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Green, J. D., & Campbell, W. K. (2000). Attachment and exploration in adults: Chronic and contextual accessibility. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 26(4), 452–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardin, E. E., Bayer, I. K., Nixon, A. E., & Robitschek, C. (2003, August 27). Self-discrepancy and distress: The role of personal growth initiative. 111th Annual Convention of the American Psychological Association, Toronto, ON, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Harmon-Jones, E., Harmon-Jones, C., & Price, T. F. (2013). What is approach motivation? Emotion Review, 5(3), 291–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hepper, E. G., & Dennis, A. (2023). From rosy past to happy and flourishing present: Nostalgia as a resource for hedonic and eudaimonic wellbeing. Current Opinion in Psychology, 49, 101547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hepper, E. G., Ritchie, T. D., Sedikides, C., & Wildschut, T. (2012). Odyssey’s end: Lay conceptions of nostalgia reflect its original Homeric meaning. Emotion, 12(1), 102–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hepper, E. G., Sedikides, C., Wildschut, T., Cheung, W. Y., Abakoumkin, G., Arikan, G., Aveyard, M., Baldursson, E. B., Bialobrzeska, O., Bouamama, S., Bouzaouech, I., Brambilla, M., Burger, A. M., Chen, S. X., Cisek, S., Demassosso, D., Estevan-Reina, L., González Gutiérrez, R., Gu, L., … Zengel, B. (2024). Pancultural nostalgia in action: Prevalence, triggers, and psychological functions of nostalgia across cultures. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 153(3), 754–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hepper, E. G., Wildschut, T., Sedikides, C., Ritchie, T. D., Yung, Y.-F., Hansen, N., Abakoumkin, G., Arikan, G., Cisek, S. Z., Demassosso, D. B., Gebauer, J. E., Gerber, J. P., González, R., Kusumi, T., Misra, G., Rusu, M., Ryan, O., Stephan, E., Vingerhoets, A. J. J. M., & Zhou, X. (2014). Pancultural nostalgia: Prototypical conceptions across cultures. Emotion, 14(4), 733–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hepper, E. G., Wildschut, T., Sedikides, C., Robertson, S., & Routledge, C. D. (2021). Time capsule: Nostalgia shields psychological wellbeing from limited time horizons. Emotion, 21(3), 644–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herman, A. (2009). The pessimist persuasion. The Wilson Quarterly, 33(2), 59–66. [Google Scholar]

- Holbrook, M. B. (1993). Nostalgia and consumption preferences: Some emerging patterns of consumer tastes. Journal of Consumer Research, 20(2), 245–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holbrook, M. B., & Schindler, R. M. (1994). Age, sex, and attitude toward the past as predictors of consumers’ aesthetic tastes for cultural products. Journal of Marketing Research, 31(3), 412–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, E. K., Sedikides, C., & Wildschut, T. (2021). Nostalgia strengthens global self-continuity through holistic thinking. Cognition and Emotion, 35(4), 730–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, E. K., Sedikides, C., & Wildschut, T. (2022). How does nostalgia conduce to global self-continuity? The roles of identity narrative, associative links, and stability. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 48(5), 735–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, E. K., Zhang, Y., & Sedikides, C. (2024). Future self-continuity promotes meaning in life through authenticity. Journal of Research in Personality, 109, 104463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X., Huang, Z., & Wyer, R. S., Jr. (2016). Slowing down in the good old days: The effect of nostalgia on consumer patience. Journal of Consumer Research, 43(3), 372–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inglehart, R. (2018). Cultural evolution: People’s Motivations are changing, and reshaping the world. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kashdan, T. B., Gallagher, M. W., Silvia, P. J., Winterstein, B. P., Breen, W. E., Terhar, D., & Steger, M. F. (2009). The Curiosity and Exploration Inventory-II: Development, factor structure, and psychometrics. Journal of Research in Personality, 43(6), 987–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelley, N. J., Davis, W. E., Dang, J., Liu, L., Wildschut, T., & Sedikides, C. (2022). Nostalgia confers psychological wellbeing by increasing authenticity. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 102, 104379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Layous, K., & Kurtz, J. L. (2023). Nostalgia: A potential pathway to greater well-being. Current Opinion in Psychology, 49, 101548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, R. M., & Walls, T. (1999). Revisiting Individuals as producers of their environment: From dynamic interactionalism to developmental systems. In J. Brandtstadter, & R. M. Lerner (Eds.), Action and self-development: Theory and research through the life span (pp. 3–36). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Leunissen, J. M., Wildschut, T., Sedikides, C., & Routledge, C. (2021). The hedonic character of nostalgia: An integrative data analysis. Emotion Review, 13(2), 139–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslow, A. H. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review, 50(4), 370–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastroianni, A. M., & Gilbert, D. T. (2023). The illusion of moral decline. Nature, 618, 782–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milojević, I. (2021). Futures fallacies: What they are and what we can do about them. Journal of Future Studies, 25(4), 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, D. B., Sachs, M. E., Stone, A. A., & Schwarz, N. (2020). Nostalgia and well-being in daily life: An ecological validity perspective. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 118(2), 325–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborn, H., Markman, K. D., & Howell, J. L. (2020). Nostalgia and temporal self-appraisal: Divergent evaluations of past and present selves. Self and Identity, 21(2), 163–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panksepp, J. (1998). Affective neuroscience: The foundations of human and animal emotions. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Protzko, J., & Schooler, J. W. (2019). Kids these days: Why the youth of today seem lacking. Science Advances, 5, eaav5916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, R. D. (2000). Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American community. Simon & Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Robitschek, C. (1998). Personal growth initiative: The construct and its measure. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development, 30(4), 183–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robitschek, C., Ashton, M. W., Spering, C. C., Geiger, N., Byers, D., Schotts, G. C., & Thoen, M. A. (2012). Development and psychometric evaluation of the Personal Growth Initiative Scale–II. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 59(2), 274–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robitschek, C., & Cook, S. W. (1999). The influence of personal growth initiative and coping styles on career exploration and vocational identity. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 54(1), 127–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schönbrodt, F. D., & Perugini, M. (2013). At what sample size do correlations stabilize? Journal of Research in Personality, 47(5), 609–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedikides, C., Cheung, W. Y., Wildschut, T., Hepper, E. G., Baldursson, E., & Pedersen, B. (2018). Nostalgia motivates pursuit of important goals by increasing meaning in life. European Journal of Social Psychology, 48(2), 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedikides, C., & Hepper, E. G. D. (2009). Self-improvement. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 3(6), 899–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedikides, C., Hong, E., & Wildschut, T. (2023). Self-continuity. Annual Review of Psychology, 74, 333–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedikides, C., & Wildschut, T. (2016a). Nostalgia: A bittersweet emotion that confers psychological health benefits. In A. M. Wood, & J. Johnson (Eds.), Wiley handbook of positive clinical psychology (pp. 25–36). Wiley Blackwell. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedikides, C., & Wildschut, T. (2016b). Past forward: Nostalgia as a motivational force. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 20(5), 319–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedikides, C., & Wildschut, T. (2018). Finding meaning in nostalgia. Review of General Psychology, 22(1), 48–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedikides, C., & Wildschut, T. (2019). The sociality of personal and collective nostalgia. European Review of Social Psychology, 30(1), 123–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedikides, C., & Wildschut, T. (2020). The motivational potency of nostalgia: The future is called yesterday. Advances in Motivation Science, 7, 75–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedikides, C., & Wildschut, T. (2023). The psychological, social, and societal relevance of nostalgia. Current Opinion in Psychology, 52, 101609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedikides, C., & Wildschut, T. (2024). Trait nostalgia. Personality and Individual Differences, 221, 112554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedikides, C., & Wildschut, T. (in press). Nostalgia: The existential value of temporal longing. In K. Vail, D. Van Tongeren, B. Schlegel, J. Greenberg, L. King, & R. Ryan (Eds.), Handbook of the science of existential psychology. Guilford Press.

- Sedikides, C., Wildschut, T., Routledge, C., Arndt, J., Hepper, E. G., & Zhou, X. (2015). To nostalgize: Mixing memory with affect and desire. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 51, 189–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharot, T. (2011). The optimism bias. Current Biology, 21(23), R941–R945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Showalter, E. (1990). Sexual anarchy, gender and culture at the fin de siecle. Viking Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stephan, E., Wildschut, T., Sedikides, C., Zhou, X., He, W., Routledge, C., Cheung, W.-Y., & Vingerhoets, A. J. J. M. (2014). The mnemonic mover: Nostalgia regulates avoidance and approach motivation. Emotion, 14(3), 545–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, B. B. (1992). Historical and personal nostalgia in advertising text: The fin de siecle effect. Journal of Advertising, 21(4), 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twenge, J. M., Campbell, W. K., & Carter, N. T. (2014). Declines in trust in others and confidence in institutions among American adults and late adolescents, 1972-2012. Psychological Science, 25(10), 1914–1923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dijke, M., Leunissen, J. M., Wildschut, T., & Sedikides, C. (2019). Nostalgia promotes intrinsic motivation and effort in the presence of low interaction justice. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 150, 46–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Tilburg, W. A. P., Wildschut, T., & Sedikides, C. (2018). Nostalgia’s place among self-conscious emotions. Cognition and Emotion, 32(4), 742–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weigold, I. K., Porfeli, E. J., & Weigold, A. (2013). Examining tenets of personal growth initiative using the Personal Growth Initiative Scale–II. Psychological Assessment, 25(4), 1396–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weigold, I. K., & Robitschek, C. (2011). Agentic personality characteristics and coping: Their relation to trait anxiety in college students. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 81(2), 255–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weigold, I. K., Weigold, A., Russell, E. J., Wolfe, G. L., Prowell, J. L., & Martin-Wagar, C. A. (2020). Personal growth initiative and mental health: A meta-analysis. Journal of Counseling & Development, 98(4), 376–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whissen, T. R. (1989). The devil’s advocates: Decadence in modern literature. Greenwood Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wildschut, T., & Sedikides, C. (2022a). Psychology and nostalgia: Towards a functional approach. In M. H. Jacobsen (Ed.), Intimations of nostalgia: Multidisciplinary explorations of an enduring emotion (pp. 110–128). Bristol University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wildschut, T., & Sedikides, C. (2022b). The measurement of nostalgia. In W. Ruch, A. B. Bakker, L. Tay, & F. Gander (Eds.), Handbook of positive psychology assessment. Hogrefe. [Google Scholar]

- Wildschut, T., & Sedikides, C. (2025). Psychology and nostalgia: A primer on experimental nostalgia inductions. In T. Becker, & D. Trigg (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of nostalgia (pp. 54–69). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Wildschut, T., Sedikides, C., Arndt, J., & Routledge, C. (2006). Nostalgia: Content, triggers, functions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 91(5), 975–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wildschut, T., Sedikides, C., & Kelley, N. J. (2023). Trait nostalgia: Four scales and a recommendation. Current Opinion in Psychology, 52, 101608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, Y., Jiang, T., Wildschut, T., & Sedikides, C. (2025). Nostalgia, ritual engagement, and meaning in life. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 51(10), 1884–1896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Condition | Variable | M (SD) | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SNS (n = 270) | 1. Nostalgia | 5.00 (1.16) | 0.09 | 0.22 *** | 0.03 | −0.11 |

| 2. Declinism | 3.13 (0.82) | −0.43 *** | −0.09 | −0.04 | ||

| 3. Personal Growth | 5.66 (0.67) | 0.13 * | −0.09 | |||

| 4. Age | 31.09 (8.24) | −0.13 * | ||||

| 5. Gender | − | |||||

| NI (n = 270) | 1. Nostalgia | 5.23 (0.61) | −0.05 | 0.40 *** | 0.06 | −0.03 |

| 2. Declinism | 3.23 (0.76) | −0.46 *** | −0.09 | 0.02 | ||

| 3. Personal Growth | 5.54 (0.78) | 0.17 ** | −0.06 | |||

| 4. Age | 30.21 (8.43) | 0.05 | ||||

| 5. Gender | − | |||||

| PINE (n = 270) | 1. Nostalgia | 4.63 (1.21) | 0.32 *** | −0.08 | −0.04 | −0.04 |

| 2. Declinism | 3.17 (0.81) | −0.49 *** | −0.11 | 0.15 * | ||

| 3. Personal Growth | 5.56 (0.76) | 0.12 * | −0.19 ** | |||

| 4. Age | 30.91 (9.14) | −0.14 * | ||||

| 5. Gender | − |

| Correlation of Nostalgia with | Condition | Difference | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SNS | NI | PINE | |ZSNS-PINE| | |ZNI-PINE| | |ZSNS-NI| | |

| Declinism | 0.09 | −0.05 | 0.32 *** | 2.79 ** | 4.41 *** | 1.62 |

| Personal Growth | 0.22 *** | 0.40 *** | −0.08 | 3.51 *** | 5.82 *** | 2.31 * |

| Model No. | χ2 (df) | p | RMSEA | CFI | TLI | SRMR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M0 | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| M1 | 34.80 (2) | <0.001 | 0.246 | 0.888 | 0.498 | 0.047 |

| M2 | 22.23 (1) | <0.001 | 0.280 | 0.928 | 0.350 | 0.039 |

| M3 | 4.47 (1) | 0.034 | 0.113 | 0.988 | 0.894 | 0.018 |

| M4 | 34.80 (1) | <0.001 | 0.354 | 0.885 | −0.035 | 0.047 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Feng, Z.; Wildschut, T.; Sedikides, C.; Dang, J. Diverging Paths to the Self: The Distinct Psychological Roles of Nostalgia and Declinism in Personal Growth. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1388. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101388

Feng Z, Wildschut T, Sedikides C, Dang J. Diverging Paths to the Self: The Distinct Psychological Roles of Nostalgia and Declinism in Personal Growth. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(10):1388. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101388

Chicago/Turabian StyleFeng, Zhuo, Tim Wildschut, Constantine Sedikides, and Jianning Dang. 2025. "Diverging Paths to the Self: The Distinct Psychological Roles of Nostalgia and Declinism in Personal Growth" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 10: 1388. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101388

APA StyleFeng, Z., Wildschut, T., Sedikides, C., & Dang, J. (2025). Diverging Paths to the Self: The Distinct Psychological Roles of Nostalgia and Declinism in Personal Growth. Behavioral Sciences, 15(10), 1388. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101388