Brief and Valid? Testing the SDQ for Measuring General Psychopathology in Children

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ)

2.3.2. Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL)

2.4. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

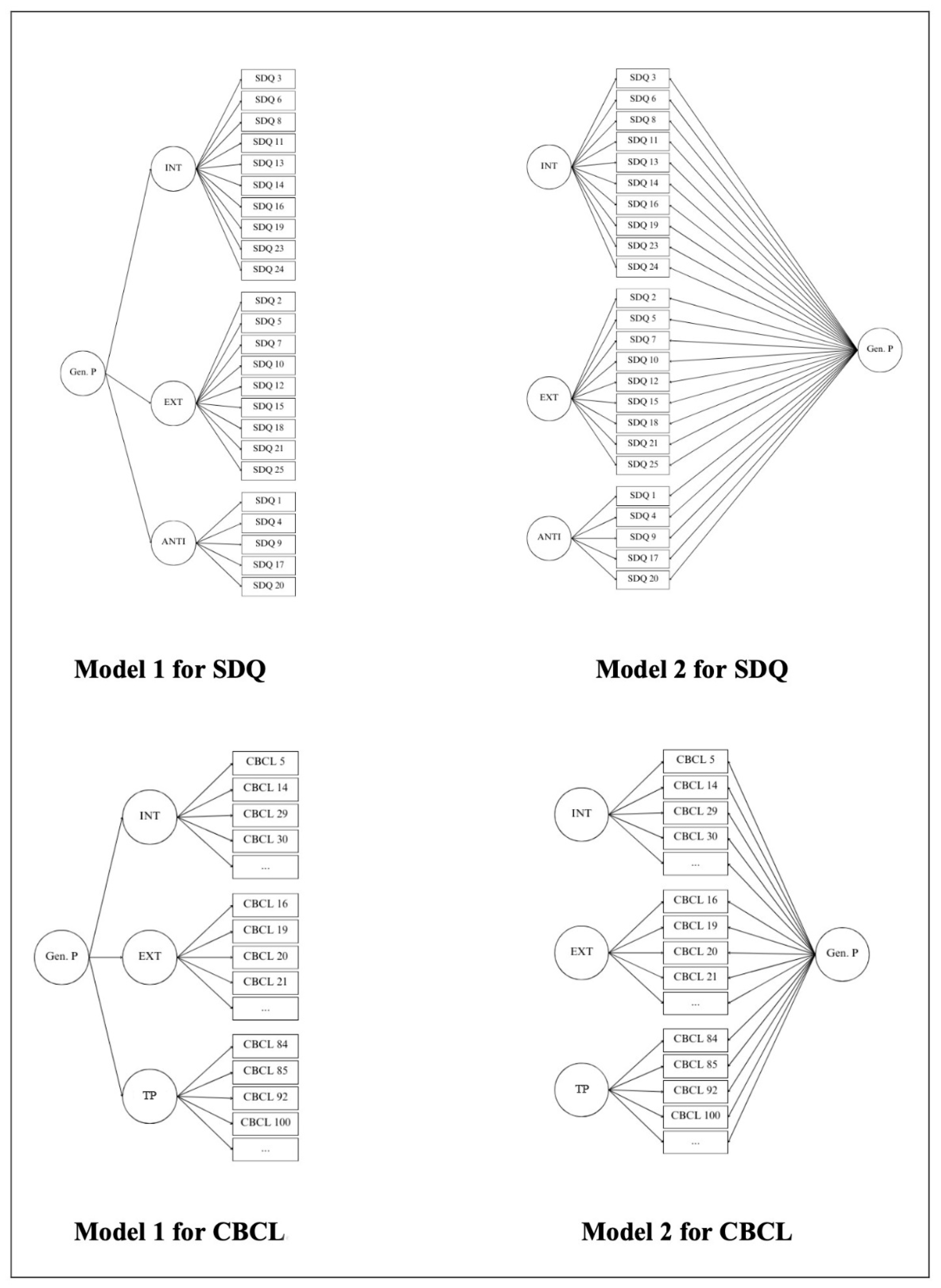

3.2. Confirmatory Factor Analyses (CFA)

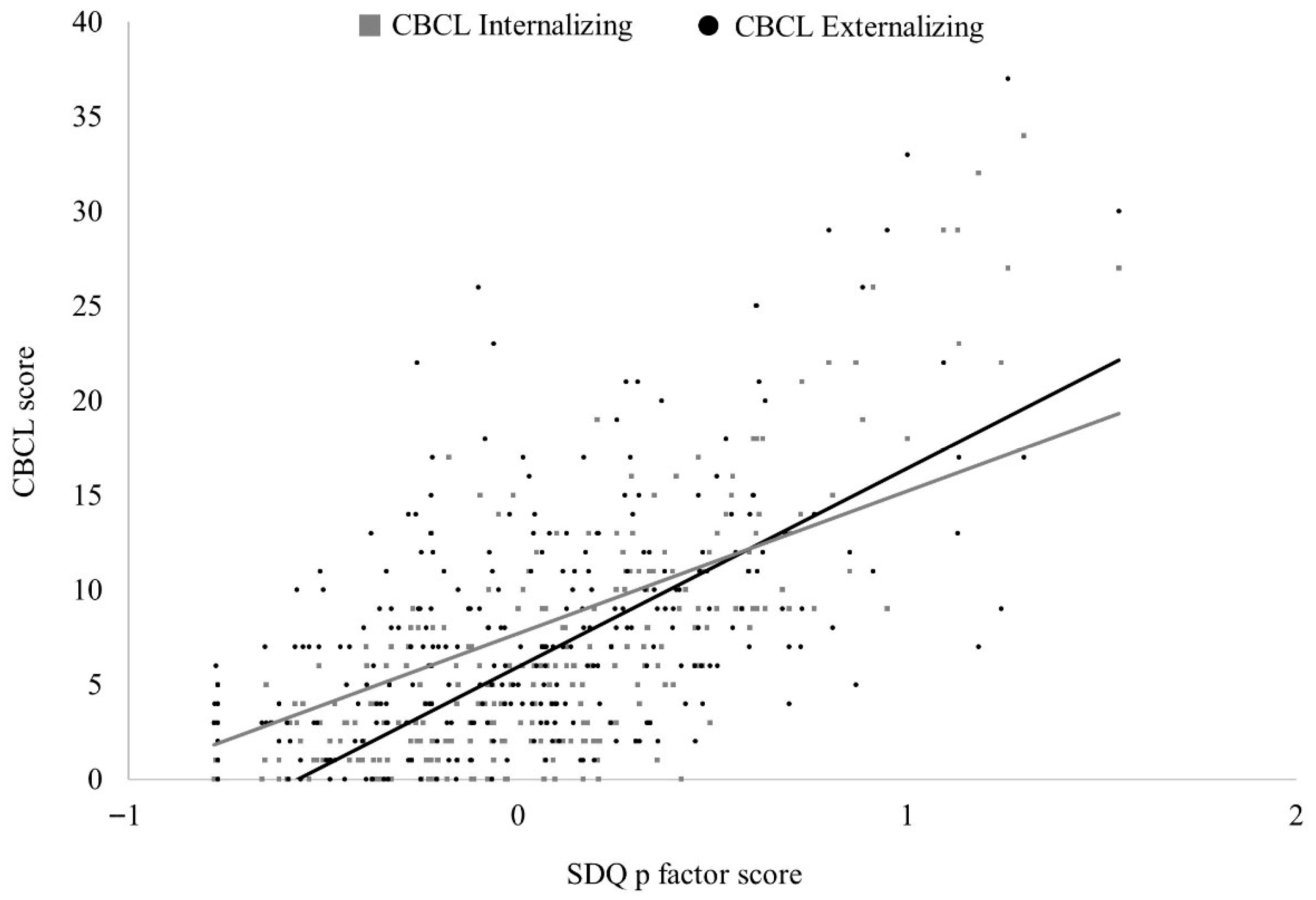

3.3. Concurrent Validity

4. Discussion

Limitations and Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Achenbach, T. M. (1991). Manual for the child behavior checklist/4-18 and 1991 profile. University of Vermont. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach, T. M., Becker, A., Döpfner, M., Heiervang, E., Roessner, V., Steinhausen, H.-C., & Rothenberger, A. (2008). Multicultural assessment of child and adolescent psychopathology with ASEBA and SDQ instruments: Research findings, applications, and future directions. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 49(3), 251–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achenbach, T. M., & Rescorla, L. A. (2001). Manual for the ASEBA school-age forms & profiles. University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, and Families. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach, T. M., & Rescorla, L. A. (2007). Multicultural understanding of child and adolescent psychopathology: Implications for mental health assessment. Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Afzali, M. H., Sunderland, M., Carragher, N., & Conrod, P. (2017). The structure of psychopathology in early adolescence: Study of a Canadian sample. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 63(4), 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, M. F., Ramírez, F. B., Misol, R. C., Bentata, L. C., Campayo, J. G., Franco, C. M., & García, J. L. T. (2012). Prevención de los trastornos de la salud mental. Atención Primaria, 44, 52–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Beauducel, A., & Herzberg, P. Y. (2006). On the performance of maximum likelihood versus mean and variance adjusted weighted least squares estimation in CFA. Structural Equation Modeling, 13(2), 186–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentler, P. M., & Chou, C.-H. (1987). Practical issues in structural modeling. Sociological Methods & Research, 16, 78–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boomsma, A. (1982). Robustness of LISREL against small sample sizes in factor analysis models. In K. G. Jöreskog, & H. Wold (Eds.), Systems under indirect observation: Causality, structure, prediction (Part I) (pp. 149–173). North-Holland. [Google Scholar]

- Boomsma, A. (1985). Nonconvergence, improper solutions, and starting values in LISREL maximum likelihood estimation. Psychometrika, 50, 229–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T. A. (2015). Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research (2nd ed.). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Carragher, N., Teesson, M., Sunderland, M., Newton, N. C., Krueger, R. F., Conrod, P. J., Barrett, E. L., Champion, K. E., Nair, N. K., & Slade, T. (2015). The structure of adolescent psychopathology: A symptom-level analysis. Psychological Medicine, 46(5), 981–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caspi, A., Houts, R., Belsky, D. W., Goldman-Mellor, S., Harrington, H., Israel, S., Meier, M. H., Ramrakha, S., Shalev, I., Poulton, R., & Moffitt, T. E. (2014). The p factor. Clinical Psychological Science, 2(2), 119–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caspi, A., Houts, R. M., Fisher, H. L., Danese, A., & Moffitt, T. E. (2024). The general factor of psychopathology (p): Choosing among competing models and interpreting p. Clinical Psychological Science, 12(1), 53–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caspi, A., & Moffitt, T. E. (2018). All for one and one for all: Mental disorders in one dimension. American Journal of Psychiatry, 175(9), 831–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellanos-Ryan, N., Brière, F. N., O’Leary-Barrett, M., Banaschewski, T., Bokde, A. L., Bromberg, U., Büchel, C., Flor, H., Frouin, V., Gallinat, J., Garavan, H., Martinot, J.-L., Nees, F., Paus, T., Pausova, Z., Rietschel, M., Smolka, M. N., Robbins, T. W., Whelan, R., … The IMAGEN Consortium. (2016). The structure of psychopathology in adolescence and its common personality and cognitive correlates. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 125(8), 1039–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De la Cruz, L. F., Vidal-Ribas, P., Zahreddine, N., Mathiassen, B., Brøndbo, P. H., Simonoff, E., Goodman, R., & Stringaris, A. (2017). Should clinicians split or lump psychiatric symptoms? The structure of psychopathology in two large pediatric clinical samples from England and Norway. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 49(4), 607–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eaton, N. R., Bringmann, L. F., Elmer, T., Fried, E. I., Forbes, M. K., Greene, A. L., Krueger, R. F., Kotov, R., McGorry, P. D., Mei, C., & Waszczuk, M. A. (2023). A review of approaches and models in psychopathology conceptualization research. Nature Reviews Psychology, 2(10), 622–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, P., Goodman, R., Mazaira, J., Torres, A., Rodríguez-Sacristán, J., Hervas, A., & Fuentes, J. (2000). El cuestionario de capacidades y dificultades. Revista de Psiquiatría Infanto-Juvenil, 1(1), 12–17. Available online: https://aepnya.eu/index.php/revistaaepnya/article/view/443 (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Goodman, R. (1997). The strengths and difficulties questionnaire: A research note. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 38(5), 581–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, R., Ford, T., Richards, H., Gatward, R., & Meltzer, H. (2000). The development and well-being assessment: Description and initial validation of an integrated assessment of child and adolescent psychopathology. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 41(5), 645–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, R., & Scott, S. (1999). Comparing the strengths and difficulties questionnaire and the child behavior checklist: Is small beautiful? Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 27(1), 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6(1), 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapadia, M., Desai, M., & Parikh, R. M. (2020). Fractures in the framework: Limitations of classification systems in psychiatry. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 22(1), 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenny, D. A., & McCoach, D. B. (2003). Effect of the number of variables on measures of fit in structural equation modeling. Structural Equation Modeling, 10(3), 333–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koskelainen, M., Sourander, A., & Kaljonen, A. (2000). The strengths and difficulties questionnaire among Finnish school-aged children and adolescents. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 9(4), 277–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, R. F., Caspi, A., Moffitt, T. E., & Silva, P. A. (1998). The structure and stability of common mental disorders (DSM-III-R): A longitudinal-epidemiological study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 107, 216–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laceulle, O. M., Vollebergh, W., & Ormel, J. (2015). The structure of psychopathology in adolescence. Clinical Psychological Science, 3(6), 850–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahey, B. B., Applegate, B., Hakes, J. K., Zald, D. H., Hariri, A. R., & Rathouz, P. J. (2012). Is there a general factor of prevalent psychopathology during adulthood? Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 121(4), 971–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laugen, N. J., Midtli, H., Löfkvist, U., & Stensen, K. (2024). Psychometric properties of the Norwegian version of the strengths and difficulties questionnaire in a preschool sample. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry, 78(6), 482–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lilienfeld, S. O., & Treadway, M. T. (2016). Clashing diagnostic approaches: DSM-ICD versus RDoC. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 12, 435–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mansolf, M., Blackwell, C. K., Cummings, P., Choi, S., & Cella, D. (2022). Linking the child behavior checklist to the strengths and difficulties questionnaire. Psychological Assessment, 34(3), 233–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (2017). Mplus user’s guide (8th ed.). Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally, J. C. (1967). Psychometric theory. McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Patalay, P., Fonagy, P., Deighton, J., Belsky, J., Vostanis, P., & Wolpert, M. (2015). A general psychopathology factor in early adolescence. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 207(1), 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sardinero García, E., Pedreira Massa, J. L., & Muñiz, J. (1997). El cuestionario CBCL de achenbach: Adaptación española y aplicaciones clínico-epidemiológicas. Clínica y Salud, 8(3), 447–480. [Google Scholar]

- Stochl, J., Khandaker, G. M., Lewis, G., Perez, J., Goodyer, I. M., Zammit, S., Sullivan, S., Croudace, T. J., & Jones, P. B. (2015). Mood, anxiety and psychotic phenomena measure a common psychopathological factor. Psychological Medicine, 45(7), 1483–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullman, J. B. (2001). Structural equation modeling. In B. G. Tabachnick, & L. S. Fidell (Eds.), Using multivariate statistics (pp. 653–771). Allyn & Bacon. [Google Scholar]

- Verhulst, F. C., & Achenbach, T. M. (1995). Empirically based assessment and taxonomy of psychopathology: Cross-cultural applications. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 4(2), 61–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts, A. L., Greene, A. L., Bonifay, W., & Fried, E. I. (2024). A critical evaluation of the p-factor literature. Nature Reviews Psychology, 3, 108–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, E. J., Harrington, K. M., Clark, S. L., & Miller, M. W. (2013). Sample size requirements for structural equation models. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 73(6), 913–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, A. G., Krueger, R. F., Hobbs, M. J., Markon, K. E., Eaton, N. R., & Slade, T. (2013). The structure of psychopathology: Toward an expanded quantitative empirical model. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 122(1), 281–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| N Items | M | (SD) | Min. | Max. | Cronbach’s Alpha | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SDQ scales | ||||||

| Emotional Problems | 5 | 1.63 | (1.66) | 0 | 9 | 0.60 |

| Peer Problems | 5 | 1.17 | (1.53) | 0 | 7 | 0.62 |

| Behavioral Problems | 5 | 1.07 | (1.40) | 0 | 7 | 0.64 |

| Hyperactivity | 5 | 3.45 | (2.57) | 0 | 7 | 0.81 |

| Prosocial Behavior | 5 | 8.16 | (1.97) | 1 | 10 | 0.78 |

| CBCL scales | ||||||

| Anxious/Depressed | 13 | 4.15 | (3.34) | 0 | 17 | 0.72 |

| Withdrawn/Depressed | 8 | 1.95 | (2.45) | 0 | 14 | 0.77 |

| Somatic Complaints | 11 | 1.85 | (1.98) | 0 | 14 | 0.59 |

| Social Problems | 11 | 2.49 | (2.51) | 0 | 12 | 0.69 |

| Thought Problems | 15 | 2.09 | (2.34) | 0 | 15 | 0.60 |

| Attention Problems | 10 | 4.07 | (3.46) | 0 | 16 | 0.81 |

| Rule-Breaking Behavior | 12 | 1.32 | (1.70) | 0 | 9 | 0.61 |

| Aggressive Behavior | 18 | 4.98 | (5.01) | 0 | 27 | 0.89 |

| Other problems | 15 | 3.33 | (2.61) | 0 | 14 | 0.58 |

| Internalizing | 32 | 7.95 | (6.29) | 0 | 37 | 0.85 |

| Externalizing | 30 | 6.29 | (6.30) | 0 | 34 | 0.89 |

| Model | χ2 | χ2/df | SRMR | RMSEA | CFI | TLI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SDQ | Model 1 | 633.70 | 2.54 | 0.11 | 0.07 | 0.84 | 0.83 |

| Model 2 | 395.89 | 1.72 | 0.08 | 0.05 | 0.93 | 0.92 | |

| CBCL | Model 1 | 7503.52 | 2.6 | 0.36 | 0.08 | 0.45 | 0.43 |

| Model 2 | 6496.17 | 2.34 | 0.34 | 0.07 | 0.56 | 0.54 |

| P Factor | CBCL Scale | Spearman Correlation |

|---|---|---|

| P | Anxious/Depressed | 0.47 ** |

| P | Withdrawn | 0.44 ** |

| P | Somatic Complaints | 0.23 ** |

| P | Social Problems | 0.57 ** |

| P | Thought Problems | 0.44 ** |

| P | Attention Problems | 0.65 ** |

| P | Rule-Breaking Behavior | 0.58 ** |

| P | Aggressive Behavior | 0.66 ** |

| P | Other Problems | 0.46 ** |

| P | Internalizing | 0.50 ** |

| P | Externalizing | 0.69 ** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Copoví-Gomila, V.; Morillas-Romero, A.; López Penadés, R.; Ollers-Adrover, M.d.À.; Balle, M. Brief and Valid? Testing the SDQ for Measuring General Psychopathology in Children. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1387. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101387

Copoví-Gomila V, Morillas-Romero A, López Penadés R, Ollers-Adrover MdÀ, Balle M. Brief and Valid? Testing the SDQ for Measuring General Psychopathology in Children. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(10):1387. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101387

Chicago/Turabian StyleCopoví-Gomila, Victòria, Alfonso Morillas-Romero, Raül López Penadés, María del Àngels Ollers-Adrover, and Maria Balle. 2025. "Brief and Valid? Testing the SDQ for Measuring General Psychopathology in Children" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 10: 1387. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101387

APA StyleCopoví-Gomila, V., Morillas-Romero, A., López Penadés, R., Ollers-Adrover, M. d. À., & Balle, M. (2025). Brief and Valid? Testing the SDQ for Measuring General Psychopathology in Children. Behavioral Sciences, 15(10), 1387. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101387