A Dynamic Approach to Compulsive Fantasy: Constraints and Creativity in “Maladaptive Daydreaming”

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Conceptualizing Fantasy and Its Relationship to Daydreaming

Fantasies can play out on any theme, but narrativity, emotional gratification, and identification can distinguish fantasies from other immersive imaginings. For example, one can immersively imagine how an audition might go without fantasizing about it. However, the same scene will become a fantasy if the imaginer relishes the gratifying imaginative experience of astonishing the judges and becoming a star, for example. Daydreams can share content with fantasies and therefore cannot be distinguished based on thought contents alone. However, fantasizing and daydreaming characteristically differ in terms of the constraints that shape their dynamic unfolding.“I have my own world in my head where I am a charismatic beautiful super model of a different race who can get anyone they want romantically. I have many genuine friends and make them easily. I am wealthy, intelligent, successful, happy.”

Especially when they are crafted by skilled imaginers (Kind, 2020), immersive fantasies can compete with everyday life and monopolize cognitive resources.“I am really scared that I may start daydreaming wile driving especially when I am alone I haven’t driven alone yet but I am scared that I will get lost in my thoughts and get into accident”

3. Automatic Constraints During Compulsive Fantasy Onset

Through engaging with fantasy related to ongoing emotions, compulsive fantasizers may find a safe place to cope with these emotions and achieve a sense of agency through active participation in a storyline–something they might not otherwise be able to achieve in everyday life. There is evidence that processing emotions in this way may be beneficial for emotional regulation skills and feelings of social connectedness (Poerio et al., 2015, 2016). Those who experience less agency in the real world, and especially those who struggle to manage traumatic experiences or extreme loneliness, may be more susceptible to relying on compulsive fantasy for emotional regulation. Traumatic experiences in childhood and social anxiety have been identified as potential predictor for the development of compulsive fantasy (Somer & Herscu, 2017). Compulsive fantasizers often report that real-world negative emotions prompt them to begin fantasizing as a form of escape or coping (Somer, 2002; Wen et al., 2024). The affective salience of a situation may prompt an emotion-regulating fantasy, perhaps through a storyline that simulates satisfaction or control unattainable in everyday life. As compulsive fantasy is often used to cope with difficult realities, it is likely that affective salience is a primary automatic constraint at the onset of compulsive fantasy episodes.“I’ll often find that I’m subconsciously drawn to a scene where one of the characters is feeling an emotion that I’m feeling in real life. I think it’s my mind’s way of processing emotions”

Even when this form of relief or escape is not initially sought compulsively, over time and repeated experiences, the process of fantasizing to emotionally regulate can become habitual, strengthening feelings of compulsion towards engaging in fantasy due to the additional automatic constraints of habit (Todd et al., 2012). Due to these heightened automatic constraints, initially easeful and freely chosen fantasizing can, in time, become compulsive. This strengthening of automatic constraints may be similar to the reinforcement that occurs in addictions. As one Reddit user self-identifying as a MDer attests:“my brain has sort of been trained to escape into daydreams whenever I’m stressed, bored, or overwhelmed”

In fact, compulsive fantasy has been conceptualized as a behavioural addiction due to its compulsive nature and detrimental effects (Pietkiewicz et al., 2018; Somer & Herscu, 2017). In the context of addiction, cravings are highly automatized forms of thought that arise in response to cues, environments, or behaviours associated with the addiction (Burrell et al., 2025; Renaud et al., 2021). Like cravings, urges to engage in compulsive fantasy are often triggered by music, media, or real-world situations (Bigelsen & Schupak, 2011), as exemplified by the following quotation from a self-identified MDer:“It’s not just a habit but also an addiction and automatic brain response”

As fantasy sessions become more regular, habitual compulsions may strengthen and detrimental effects may appear. Further engaging with the behavioural addiction may exacerbate the cycle: fantasizing comes to occupy an average of 56% of waking hours for compulsive fantasizers (Bigelsen et al., 2016; Bigelsen & Schupak, 2011), taking the place of real-world social interaction and the pursuit of other life projects. This may, in turn, increase feelings of loneliness and helplessness, generating negative affect, which can trigger more powerful and frequent urges to fantasize. In fact, compulsive fantasizers reported significantly stronger urges to return to fantasizing after being interrupted, compared to control participants (Bigelsen et al., 2016; Bigelsen & Schupak, 2011). This demonstrates the automatic constraints that may be increased by the habitual process of engaging in compulsive fantasy.“Everything is a trigger. TV, music, even looking at myself in the mirror.”

4. Deliberate Constraints During Compulsive Fantasy Onset

Compulsive fantasizers often report feeling a sense of ownership over their creations and intentionally situating themselves in particular environments to promote emotional engagement and immersion (Somer et al., 2016b).“Most of my daydreaming episodes comes with the conscious decision and willingness to take part in these daydreams”

Bodily movement is another particularly common strategy. In Bigelsen and Schupak’s (2011) sample of compulsive fantasizers, 79% reported engaging in repetitive kinesthetic movements during fantasy episodes. Movements such as pacing, swinging, or hand movements, may act to limit the variability of the sensory experience and serve to attenuate exteroceptive sensations (Braun et al., 2005; Levin & Benton, 1973; Tannan et al., 2005), potentially clearing the way for further immersion into the internal experience (Bigelsen et al., 2016).“I realized that most of my daydreaming happens when I’m listening to songs I’m very familiar with. when i’m listening to new music, I’m more inclined to notice the lyrics or chord progression, instead of daydreaming!”

“I make the entire room dark and put my earphones and turn on whichever playlist is fitting to my current daydream.”

Another writes:“I for instance can create entire buildings and cities and keep it consistent with the help of a pinterest picture as inspiration.”

For some, these behaviours are foundational to constructing the long-term agential projects many fantasies comprise. Immersive fantasies can unfold over years or even decades, and imaginers often become profoundly emotionally attached to their creations. For example, one Reddit user shares the following:“im also an artist so i try to sketch out stuff the next day of the stories i came up with at night. i get so fixated on them i make pinterest boards and write for hours in google docs. sometimes i write movie scripts too”

Due to the prominence of these deliberate behaviours occurring beyond and before particular episodes of compulsive fantasizing, we find it difficult to paint daydreaming, fantasy, and compulsive fantasy with the same brush. There appears to be a large discrepancy between the easeful, spontaneous arising of daydreams and the high levels of deliberate guidance described by compulsive fantasizers.“After 7.5 years of being in love with my character, I’ve been wondering if I’d symbolically ‘marry’ him one day”

Compulsive fantasy is not simply an automatic behaviour or a deliberately chosen behaviour; we propose that the interplay between deliberate and automatic constraints guides the onset of compulsive fantasy. Episode onset may often occur when automatic constraints exert a pull to fantasize that is realized in part by mental and physical actions under deliberate guidance. This often occurs in tension with desires or deliberate efforts not to fantasize. Prior to the fantasy event, strong automatic constraints may drive the urge to engage in fantasy. This could be due to the affective salience of a real-world event (e.g., a negative social media post in one’s feed) or the desire to escape reality, which may precipitate the compulsion to fantasize. During this pre-fantasy period, deliberate constraints may increase in order to combat the “relentless pull of [fantasizers] imagination” (Bigelsen & Kelley, 2015). On the one hand, deliberate constraints may potentially override the automatic constraints initiating a fantasy episode and prevent it from beginning. On the other hand, however, compulsive fantasizers may use deliberate constraints, for example, to establish the scene. The interplay of constraints characterizing the onset of compulsive fantasy is distinct from the dynamics of automatic and deliberate constraints that govern the unfolding of thoughts within a fantasy. In the next section, we discuss how the dynamics of automatic and deliberate constraints facilitate the unfolding of fantasy.“I think most of us here have that intentional type, where you lock yourself in a room and start creating stories, moving your hands, walking in circles, etc. But I also realized that I have another type of daydreaming that happens very quickly and is completely out of my control, like in the movie The Secret Life of Walter Mitty. Something happens in front of me, and I automatically imagine the situation in a completely different way. Then, I “wake up” to reality.”

5. Dynamics of Thought During the Unfolding of Compulsive Fantasies

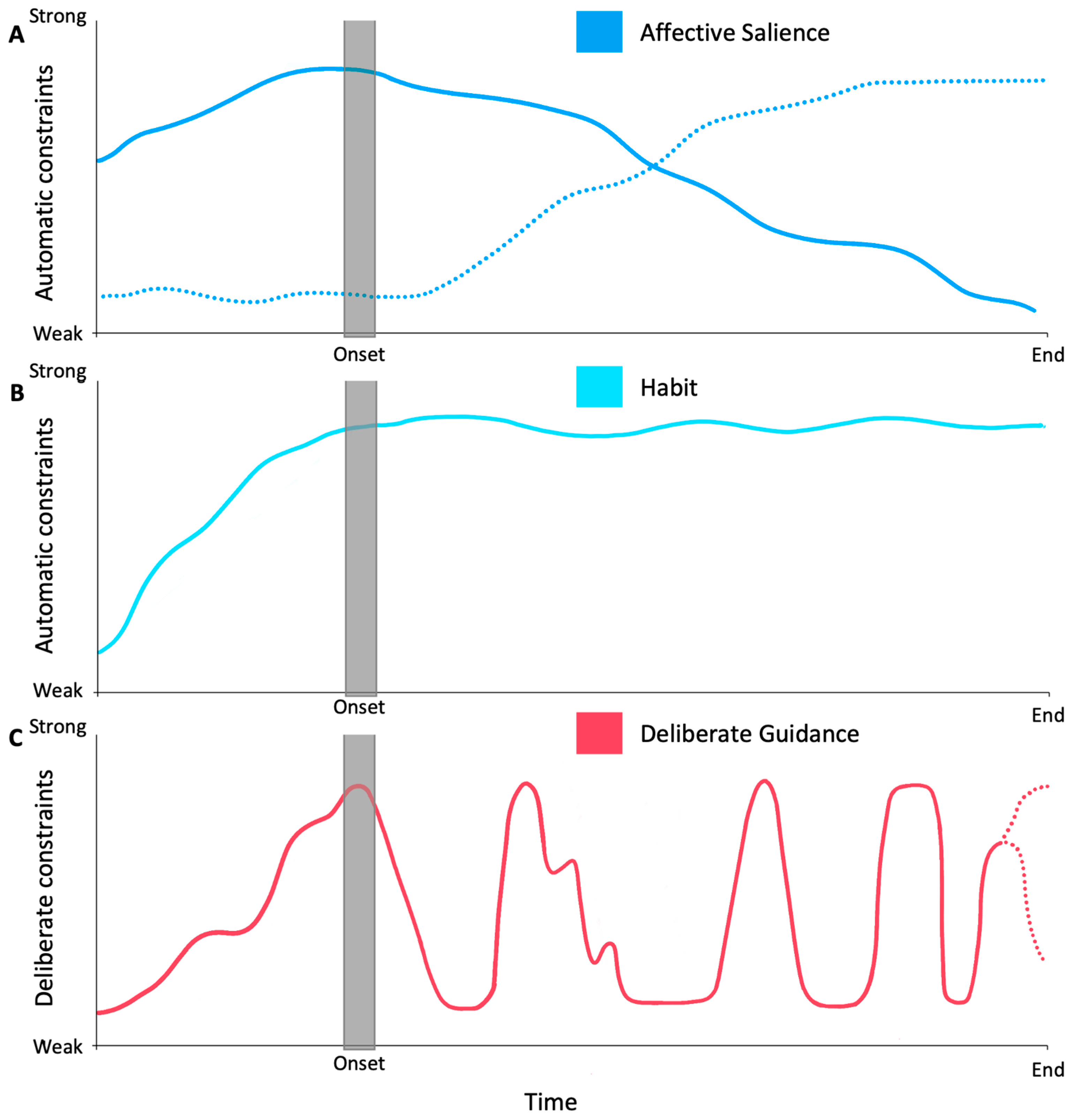

Once initiated, fantasies may unfold with relatively little deliberate guidance, guided instead by automatic constraints, such as affective salience (Figure 2A), habitual mental patterns (Figure 2B), and societal or narrative constraints (not pictured on Figure 2). In the context of an unfolding imagined story, these automatic constraints can limit the option space for the narrative’s progression. For example, an imaginer’s mood may affectively guide a narrative’s direction; a foul mood, for example, might suggest more negative fantasy content. The narratives of fantasies may also, reciprocally, shape affect and increase emotional salience. Habits formed through repeated fantasizing may suggest familiar narrative pathways. Similarly, an imaginer’s societal context may constrain the kinds of stories that seem available or appropriate. These automatic constraints likely guide the episode without necessitating a feeling of deliberate guidance.“I made a bunch of “seeds”, places, events, monsters, people. And I try to put my mind into a random person there and let it run crazy with story creation. It’s not structured, it’s hard to feel like I have control over it, but it feels like the best way to really use my daydreaming to it’s full creativity.”

This quotation demonstrates the broader struggle with agency that often characterizes compulsive fantasy. In this example, a struggle with automatic constraints pervades the fantasy itself. This struggle manifests under high levels of automatic constraints governing fantasy, countered by strong deliberate constraints. Deliberate fantasy engagement appears to be a way for compulsive fantasizers to exercise control despite compulsive fantasy feeling largely uncontrollable. The strength of deliberate constraints may oscillate across the duration of a fantasy episode, exerting a strong influence on the progression of the fantasy when engaged, and then relaxing to allow for the narrative to progress through automatic guidance.“Recently I’ve been struggling with misbehaving imagery. It feels like my mind fixates on one thing and struggles to switch, like if a character is dressed and then undresses my brain will struggle between them having fabric on and not, back and forth. It’s a conscious thing to try and correct.”

This raises the question of how fantasy episodes conclude. If fantasies are so gratifying and propulsive, how do constraints change to allow disengagement?“Any chance I had, I’d go and lie down or I’d just get sucked into it, and it was so hard to turn off. It’s like you’ve always got a tailor-made fantasy, soap opera, action film, whatever you want, playing in your head all the time. An alcoholic can run out of booze and money, but you don’t run out of mind. You can’t just tell yourself to stop thinking.”

In this case, the end of an episode appears to be brought about by strong deliberate constraints forcing thoughts away from the fantasy, or perhaps by strong external pressures contradicting the habitual constraints, such as societal pressures to maintain employment or social relationships. Other automatic constraints on thought may break absorption in the fantasy: for example, the sensory salience of being interrupted by something in the external environment, or the affective salience of feeling shame for wasting time, may be strong enough to end a fantasy episode.“I need to brush my teeth before sleeping right? I can’t bring myself to do so since I’m busy pacing around and daydreaming—but I also can’t sleep unless I brush my teeth. I go by the sink thinking “I will brush my teeth now” then I turn around and keep pacing and daydreaming again. This goes on for 2–3 h on average, and I end up sleeping very late.”

6. The Relationship Between Creative Thought and Compulsive Fantasy

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Citation Diversity Statement

Abbreviations

| DFT | Dynamic Framework of Thought |

| MDer(s) | Maladaptive Daydreamer(s)/Compulsive Fantasizer(s) |

Appendix A

Quotations from MDers

| 1 | Compulsive fantasy is often comorbid with obsessive–compulsive-related disorders. For a comprehensive examination of the interactions between compulsive fantasy and obsessive–compulsive-related disorders (see Salomon-Small et al., 2021). |

| 2 | For similar reasons, daydreaming, in virtue of involving immersive imagination, tends to be more automatically constrained than mind-wandering (Figure 1), though both remain forms of relatively unconstrained, spontaneous thought. |

| 3 | Though the author of this post and others included in this paper sometimes use the term “daydreaming” in their descriptions, they are describing instances of fantasy according to our conceptualization. |

| 4 | Immersive daydreamers are people who frequently engage in immersive imaginative fantasy similar to compulsive fantasizers, but for whom fantasy does not feel compulsive or cause distress. |

| 5 | We thank the reviewers for providing interesting suggestions for future research, including those for individual differences and the connections to dreaming. |

References

- Ambekar, A., Ward, C., Mohammed, J., Male, S., & Skiena, S. (2009, June 28). Name-ethnicity classification from open sources. 15th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining (pp. 49–58), Paris, France. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, B. A. (2019). Neurobiology of value-driven attention. Current Opinion in Psychology, 29, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews-Hanna, J., Kaiser, R., Turner, A., Reineberg, A., Godinez, D., Dimidjian, S., & Banich, M. (2013). A penny for your thoughts: Dimensions of self-generated thought content and relationships with individual differences in emotional wellbeing. Frontiers in Psychology, 4, 900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batey, M. (2007). A psychometric investigation of everyday creativity [Unpublished doctoral thesis, University College]. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/openview/ee3b530761179ef2cb8beb27b201a68e/1?cbl=2026366&pq-origsite=gscholar (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Bertolero, M. A., Dworkin, J. D., David, S. U., Lloreda, C. L., Srivastava, P., Stiso, J., Zhou, D., Dzirasa, K., Fair, D. A., Kaczkurkin, A. N., Marlin, B. J., Shohamy, D., Uddin, L. Q., Zurn, P., & Bassett, D. S. (2020). Racial and ethnic imbalance in neuroscience reference lists and intersections with gender. bioRxiv. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigelsen, J., & Kelley, T. (2015, April 29). When daydreaming replaces real life. The Atlantic. Available online: https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2015/04/when-daydreaming-replaces-real-life/391319/ (accessed on 11 April 2025).

- Bigelsen, J., Lehrfeld, J. M., Jopp, D. S., & Somer, E. (2016). Maladaptive daydreaming: Evidence for an under-researched mental health disorder. Consciousness and Cognition, 42, 254–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigelsen, J., & Schupak, C. (2011). Compulsive fantasy: Proposed evidence of an under-reported syndrome through a systematic study of 90 self-identified non-normative fantasizers. Consciousness and Cognition, 20(4), 1634–1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, C., Hess, H., Burkhardt, M., Wühle, A., & Preissl, H. (2005). The right hand knows what the left hand is feeling. Experimental Brain Research, 162(3), 366–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruineberg, J., & Fabry, R. (2022). Extended mind-wandering. Philosophy and the Mind Sciences, 3, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burrell, J., Zamani, A., & Christoff Hadjiilieva, K. (2025). Neurocognitive dynamics, mental flexibility, and constraints on thought. In A. K. Barbey (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of cognitive enhancement and brain plasticity. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, L. (2006). Normative dissociation. The Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 29, 45–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casey, E. S. (2003). Imagination, fantasy, hallucination, and memory. In J. Philips, & J. Morley (Eds.), Imagination and its pathologies (pp. 65–92). MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee, P., & Werner, R. M. (2021). Gender disparity in citations in high-impact journal articles. JAMA Network Open, 4(7), e2114509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chefetz, R. A., Soffer-Dudek, N., & Somer, E. (2023). When daydreaming becomes maladaptive: Phenomenological and psychoanalytic perspectives. Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy, 37(4), 319–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chintalapati, R., Laohaprapanon, S., & Sood, G. (2023). Predicting race and ethnicity from the sequence of characters in a name. arXiv, arXiv:1805.02109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christoff, K. (2024). Mindfulness as a way of reducing automatic constraints on thought. Biological Psychiatry. Cognitive Neuroscience and Neuroimaging, 10(4), 393–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christoff, K., & Fox, K. (2018). The Oxford handbook of spontaneous thought: Mind-wandering, creativity, and dreaming. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christoff, K., Irving, Z. C., Fox, K. C. R., Spreng, R. N., & Andrews-Hanna, J. R. (2016). Mind-wandering as spontaneous thought: A dynamic framework. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 17(11), 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christoff, K., Mills, C., Andrews-Hanna, J. R., Irving, Z. C., Thompson, E., Fox, K. C. R., & Kam, J. W. Y. (2018). Mind-wandering as a scientific concept: Cutting through the definitional haze. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 22(11), 957–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cool_Spell_2944. (2025, January 10). Am i weird for the way i immerse myself in my daydreams? [Reddit Post]. R/ImmersiveDaydreaming. Available online: https://www.reddit.com/r/ImmersiveDaydreaming/comments/1hxrrcy/am_i_weird_for_the_way_i_immerse_myself_in_my/ (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Dazzling-Ad3857. (2025, February 16). My family wants to me stop MD & immersive daydreaming [Reddit Post]. R/MaladaptiveDreaming. Available online: https://www.reddit.com/r/MaladaptiveDreaming/comments/1iqntsw/my_family_wants_to_me_stop_md_immersive/ (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Diamond_Verneshot. (2025, February 10). For me, any deeper meaning is found in the emotions rather than the specific scenario [Reddit Comment]. R/MaladaptiveDreaming. Available online: https://www.reddit.com/r/MaladaptiveDreaming/comments/1ilzz26/do_maladaptive_daydream_scenarios_have_meanings/mbzcwbi/ (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Dokic, J., & Arcangeli, M. (2014). The heterogeneity of experiential imagination. In T. K. Metzinger, & J. M. Windt (Eds.), Open MIND. Philosophy and the mind sciences in the 21st century (pp. 431–450). MIT Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorsch, F. (2015). Focused daydreaming and mind-wandering. Review of Philosophy and Psychology, 6(4), 791–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DryCoast. (2025, February 8). Having an imaginary boyfriend is so lonely and heartbreaking [Reddit Post]. R/MaladaptiveDreaming. Available online: https://www.reddit.com/r/MaladaptiveDreaming/comments/1ikbyl6/having_an_imaginary_boyfriend_is_so_lonely_and/ (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Dworkin, J. D., Linn, K. A., Teich, E. G., Zurn, P., Shinohara, R. T., & Bassett, D. S. (2020). The extent and drivers of gender imbalance in neuroscience reference lists. Nature Neuroscience, 23(8), 918–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellamil, M., Dobson, C., Beeman, M., & Christoff, K. (2012). Evaluative and generative modes of thought during the creative process. NeuroImage, 59(2), 1783–1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Few-Vegetable-7108. (2025, February 15). Anybody with similar sleep issues? [Reddit Post]. R/MaladaptiveDreaming. Available online: https://www.reddit.com/r/MaladaptiveDreaming/comments/1ippold/anybody_with_similar_sleep_issues/ (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Girn, M., Mills, C., Roseman, L., Carhart-Harris, R. L., & Christoff, K. (2020). Updating the dynamic framework of thought: Creativity and psychedelics. NeuroImage, 213, 116726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, W. K., Price, L. H., Rasmussen, S. A., Mazure, C., Fleischmann, R. L., Hill, C. L., Heninger, G. R., & Charney, D. S. (1989). The yale-brown obsessive compulsive scale. I. development, use, and reliability. Archives of General Psychiatry, 46(11), 1006–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayman, A. (1989). What do we mean by “phantasy”? The International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 70(Pt 1), 105–114. [Google Scholar]

- Irving, Z. C. (2016). Mind-wandering is unguided attention: Accounting for the “purposeful” wanderer. Philosophical Studies: An International Journal for Philosophy in the Analytic Tradition, 173(2), 547–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irving, Z. C., & Thompson, E. (2018). The philosophy of mind-wandering. In K. Christoff, & K. C. R. Fox (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of spontaneous thought: Mind-wandering, creativity, and dreaming (pp. 87–96). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- I thought for a long time I had maladaptive daydreaming, but I’m still not sure [Reddit Post]. (2025, January 7). R/ImmersiveDaydreaming. Available online: https://www.reddit.com/r/ImmersiveDaydreaming/comments/1hw1hlw/i_thought_for_a_long_time_i_had_maladaptive/ (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Karwowski, M., Lebuda, I., & Wiśniewska, E. (2018). Measuring creative self-efficacy and creative personal identity. The International Journal of Creativity & Problem Solving, 28(1), 45–57. [Google Scholar]

- Key-Acanthocephala10. (2025, February 17). Honestly it’s a bit tricky, I’m trying to use that tendency to make new worlds easily to help with the one [Comment on Reddit Post Has anybody ever tried to create a new world/paracosm by force?]. R/MaladaptiveDreaming. Available online: https://www.reddit.com/r/MaladaptiveDreaming/comments/1irqilv/has_anybody_ever_tried_to_create_a_new/ (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Key-External-9122. (2025, February 10). Two types of excessive daydreaming? [Reddit Post]. R/MaladaptiveDreaming. Available online: https://www.reddit.com/r/MaladaptiveDreaming/comments/1im4oeb/two_types_of_excessive_daydreaming/ (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Killingsworth, M. A., & Gilbert, D. T. (2010). A wandering mind is an unhappy mind. Science, 330(6006), 932–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kind, A. (2013). The Heterogeneity of the Imagination. Erkenntnis, 78(1), 141–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kind, A. (2020). The skill of imagination. In E. Fridland, & C. Pavese (Eds.), Routledge handbook of skill and expertise (pp. 335–346). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Klinger, E. (1971). Structure and functions of fantasy. Wiley-Interscience. Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1974-23015-000 (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Klinger, E. (1990). Daydreaming: Using waking fantasy and imagery for self-knowledge and creativity. J.P. Tarcher. Available online: https://go.exlibris.link/JLkNw8SB (accessed on 4 March 2025).

- Klinger, E. (2009). Daydreaming and fantasizing: Thought flow and motivation. In K. D. Markman, W. M. Klein, & J. A. Suhr (Eds.), Handbook of imagination and mental simulation (pp. 225–240). Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Kucyi, A., & Davis, K. D. (2014). Dynamic functional connectivity of the default mode network tracks daydreaming. NeuroImage, 100, 471–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, E., & Thompson, E. (2024). Daydreaming as spontaneous immersive imagination: A phenomenological analysis. Philosophy and the Mind Sciences, 5, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, H. S., & Benton, A. L. (1973). A comparison of ipsilateral and contralateral effects of tactile masking. The American Journal of Psychology, 86(2), 435–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, M. G. F. (2002). The transparency of experience. Mind and Language, 17, 376–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McVay, J. C., Kane, M. J., & Kwapil, T. R. (2009). Tracking the train of thought from the laboratory into everyday life: An experience-sampling study of mind wandering across controlled and ecological contexts. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 16(5), 857–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- midnightmoodaway. (2025, February 20). The only place where everything is right [Reddit Post]. R/MaladaptiveDreaming. Available online: https://www.reddit.com/r/MaladaptiveDreaming/comments/1ittstt/the_only_place_where_everything_is_right/ (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Milton, F., Fulford, J., Dance, C., Gaddum, J., Heuerman-Williamson, B., Jones, K., Knight, K. F., MacKisack, M., Winlove, C., & Zeman, A. (2021). Behavioral and neural signatures of visual imagery vividness extremes: Aphantasia versus hyperphantasia. Cerebral Cortex Communications, 2(2), tgab035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, S. M., Lange, S., & Brus, H. (2013). Gendered citation patterns in international relations journals. International Studies Perspectives, 14(4), 485–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MoonyDropps. (2025, February 9). Listen to music you don’t know to curb daydreaming! [Reddit Post]. R/MaladaptiveDreaming. Available online: https://www.reddit.com/r/MaladaptiveDreaming/comments/1il6hsq/listen_to_music_you_dont_know_to_curb_daydreaming/ (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Nelson, B., & Rawlings, D. (2009). How does it feel? The development of the experience of creativity questionnaire. Creativity Research Journal, 21(1), 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowacki, A., & Pyszkowska, A. (2024). The everchanging maladaptive daydreaming—A thematic analysis of lived experiences of Reddit users. Current Psychology, 43, 28488–28499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ok_Bodybuilder_8452. (2025, January 13). Unable to daydream [Reddit Post]. R/ImmersiveDaydreaming. Available online: https://www.reddit.com/r/ImmersiveDaydreaming/comments/1i01kck/unable_to_daydream/ (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Person, E. S. (1995). By force of fantasy: How we make our lives. Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Pietkiewicz, I. J., Nęcki, S., Bańbura, A., & Tomalski, R. (2018). Maladaptive daydreaming as a new form of behavioral addiction. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 7(3), 838–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poerio, G. L., Totterdell, P., Emerson, L.-M., & Miles, E. (2015). Love is the triumph of the imagination: Daydreams about significant others are associated with increased happiness, love and connection. Consciousness and Cognition, 33, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poerio, G. L., Totterdell, P., Emerson, L.-M., & Miles, E. (2016). Helping the heart grow fonder during absence: Daydreaming about significant others replenishes connectedness after induced loneliness. Cognition & Emotion, 30(6), 1197–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regis, M. (2013). Daydreams and the function of fantasy. Palgrave Macmillan. Available online: https://www.worldcat.org/title/Daydreams-and-the-function-of-fantasy/oclc/858871709 (accessed on 4 March 2025).

- Renaud, F., Jakubiec, L., Swendsen, J., & Fatseas, M. (2021). The impact of co-occurring post-traumatic stress disorder and substance use disorders on craving: A systematic review of the literature. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, 786664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rowson, B., Duma, S. M., King, M. R., Efimov, I., Saterbak, A., & Chesler, N. C. (2021). Citation diversity statement in BMES journals. Annals of Biomedical Engineering, 49(3), 947–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, A., Girija, V. S., & Kitzlerová, E. (2024). The role of momentary dissociation in the sensory cortex: A neurophysiological review and its implications for maladaptive daydreaming. Medical Science Monitor, 30, e944209-1–e944209-10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salomon-Small, G., Somer, E., Harel-Schwarzmann, M., & Soffer-Dudek, N. (2021). Maladaptive daydreaming and obsessive-compulsive symptoms: A confirmatory and exploratory investigation of shared mechanisms. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 136, 343–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schupak, C., & Rosenthal, J. (2009). Excessive daydreaming: A case history and discussion of mind wandering and high fantasy proneness. Consciousness and Cognition, 18(1), 290–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, J. L. (1975). The inner world of daydreaming. Harper and Row. [Google Scholar]

- Singer, J. L. (1976). Daydreaming and fantasy (2014 ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, J. L., & Antrobus, J. S. (1970). Imaginal processes inventory [by] Jerome L. Singer and John S. Antrobus (Rev). Center for Research in Cognition and Affect Graduate Center, City University of New York. [Google Scholar]

- Smallwood, J., & Schooler, J. W. (2015). The science of mind wandering: Empirically navigating the stream of consciousness. Annual Review of Psychology, 66, 487–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somer, E. (2002). Maladaptive daydreaming: A qualitative inquiry. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy, 32(2), 197–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somer, E., & Herscu, O. (2017). Childhood trauma, social anxiety, absorption and fantasy dependence: Two potential mediated pathways to maladaptive daydreaming. Journal of Addictive Behaviors, Therapy & Rehabilitation, 6(4), 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somer, E., Lehrfeld, J., Bigelsen, J., & Jopp, D. S. (2016a). Development and validation of the maladaptive daydreaming scale (MDS). Consciousness and Cognition, 39, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somer, E., Soffer-Dudek, N., & Ross, C. A. (2017). The comorbidity of daydreaming disorder (maladaptive daydreaming). Journal of Nervous & Mental Disease, 205(7), 525–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Somer, E., Somer, L., & Jopp, D. S. (2016b). Parallel lives: A phenomenological study of the lived experience of maladaptive daydreaming. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 17(5), 561–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spector Person, E. (2003). The creative role of fantasy in adaptation. In J. Philips, & J. Morley (Eds.), Imagination and its pathologies (pp. 111–132). MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stan, D., & Christoff, K. (2018). The mind wanders with ease: Low motivational intensity is an essential quality of mind-wandering. In K. Christoff, & K. C. R. Fox (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of spontaneous thought: Mind-wandering, creativity, and dreaming (pp. 47–53). Oxford University Press. Available online: https://academic.oup.com/edited-volume/38694/chapter/336053703?login=true (accessed on 4 March 2025).

- Stawarczyk, D., Majerus, S., Van Der Linden, M., & D’Argembeau, A. (2012). Using the daydreaming frequency scale to investigate the relationships between mind-wandering, psychological well-being, and present-moment awareness. Frontiers in Psychology, 3(363), 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J., He, L., Chen, Q., Yang, W., Wei, D., & Qiu, J. (2021). The bright side and dark side of daydreaming predict creativity together through brain functional connectivity. Human Brain Mapping, 43(3), 902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tannan, V., Dennis, R. G., & Tommerdahl, M. (2005). Stimulus-dependent effects on tactile spatial acuity. Behavioral and Brain Functions: BBF, 1, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teasdale, J. D., Dritschel, B. H., Taylor, M. J., Proctor, L., Lloyd, C. A., Nimmo-Smith, I., & Baddeley, A. D. (1995). Stimulus-independent thought depends on central executive resources. Memory & Cognition, 23(5), 551–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, E. (2007). Mind in life: Biology, phenomenology, and the sciences of mind. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, E. (2015). Waking, dreaming, being: Self and consciousness in neuroscience, meditation, and philosophy. Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Thomson, P., & Jaque, S. V. (2023). Creativity, emotion regulation, and maladaptive daydreaming. Creativity Research Journal, 37(1), 94–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiny-Supermarket5036. (2025, February 8). I have given up on quiting MD [Reddit Post]. R/MaladaptiveDreaming. Available online: https://www.reddit.com/r/MaladaptiveDreaming/comments/1il0s4m/i_have_given_up_on_quiting_md/ (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Todd, R. M., Cunningham, W. A., Anderson, A. K., & Thompson, E. (2012). Affect-biased attention as emotion regulation. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 16(7), 365–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Top-Cat6153. (2025, February 8). Driving tips needed [Reddit Post]. R/MaladaptiveDreaming. Available online: https://www.reddit.com/r/MaladaptiveDreaming/comments/1ikpwao/driving_tips_needed/ (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Tsoulis-Reay, A. (2016, October 12). What it’s like when your daydreams are just as real as life. The Cut. Available online: https://www.thecut.com/2016/10/what-its-like-to-be-a-maladaptive-daydreamer.html (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- ttaemin. (2025, February 4). Is this normal [Reddit Post]. R/ImmersiveDaydreaming. Available online: https://www.reddit.com/r/ImmersiveDaydreaming/comments/1ihbouj/is_this_normal/ (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Unlucky_Trash1685. (2025, February 16). Excessive daydreaming about fame [Reddit Post]. R/MaladaptiveDreaming. Available online: https://www.reddit.com/r/MaladaptiveDreaming/comments/1ir31vm/excessive_daydreaming_about_fame/ (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Wen, H., Soffer-Dudek, N., & Somer, E. (2024). Daily feelings and the affective valence of daydreams in maladaptive daydreaming: A longitudinal analysis. Psychology of Consciousness: Theory, Research, and Practice, 11(4), 447–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, M. J., & Somer, E. (2020). Empathy, emotion regulation, and creativity in immersive and maladaptive daydreaming. Imagination, Cognition and Personality, 39(4), 358–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windt, J. M. (2010). The immersive spatiotemporal hallucination model of dreaming. Phenomenology and the Cognitive Sciences, 9(2), 295–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- xxangelbunnyxx. (2024, October 22). Daydreams misbehaving and hard to correct [Reddit Post]. R/ImmersiveDaydreaming. Available online: https://www.reddit.com/r/ImmersiveDaydreaming/comments/1g9p332/daydreams_misbehaving_and_hard_to_correct/ (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Zamani, A., Mills, C., Girn, M., & Christoff, K. (2022). A closer look at transitions between the generative and evaluative phases of creative thought. PsyArXiv. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zedelius, C., Protzko, J., Broadway, J., & Schooler, J. (2021). What types of daydreaming predict creativity? Laboratory and experience sampling evidence. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 15(4), 596–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D., Cornblath, E. J., Stiso, J., Teich, E. G., Dworkin, J. D., Blevins, A. S., & Bassett, D. S. (2020). Gender diversity statement and code notebook v1.0 (Version v1.0) [Computer software]. Zenodo. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Burrell, J.I.; Lawson, E.; Christoff Hadjiilieva, K. A Dynamic Approach to Compulsive Fantasy: Constraints and Creativity in “Maladaptive Daydreaming”. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1333. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101333

Burrell JI, Lawson E, Christoff Hadjiilieva K. A Dynamic Approach to Compulsive Fantasy: Constraints and Creativity in “Maladaptive Daydreaming”. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(10):1333. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101333

Chicago/Turabian StyleBurrell, Jennifer I., Emily Lawson, and Kalina Christoff Hadjiilieva. 2025. "A Dynamic Approach to Compulsive Fantasy: Constraints and Creativity in “Maladaptive Daydreaming”" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 10: 1333. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101333

APA StyleBurrell, J. I., Lawson, E., & Christoff Hadjiilieva, K. (2025). A Dynamic Approach to Compulsive Fantasy: Constraints and Creativity in “Maladaptive Daydreaming”. Behavioral Sciences, 15(10), 1333. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101333