Abstract

As age increases, children will face more and more adversity. How effectively they cope with stress and difficulties of life is of great significance to the development of children’s mental health and academic achievement. However, few studies have explored how different interpersonal relationships and psychological suzhi work together to influence children’s healthy behaviors, particularly healthy coping in adversity. Therefore, this research focused on the teacher–student relationships and coping styles, as well as the chain-mediated effects of peer relationships and psychological suzhi. A total of 688 children (360 boys, 52.3%; Mage = 10.98 and SD = 0.89) completed questionnaires that assessed using teacher–student relationships, peer relationships, psychological suzhi, and coping styles. The results indicated that teacher–student relationships correlated positively with coping styles, peer relationships, and psychological suzhi in children. Besides, teacher–student relationships positively affected coping styles through both the mediating roles of peer relationships and psychological suzhi. This research elucidated the extrinsic and intrinsic factors impacting the coping styles of children, thus providing empirical validation of existing theoretical frameworks. In China, interventions aimed at promoting Chinese children’s positive coping could benefit from strategies focused on cultivating high-quality relationships and enhancing psychological suzhi.

1. Introduction

Teacher–student relationships refer to the psychological connections formed through cognitive, emotional, and behavioral interactions between educators and students [1]. Youth development was linked to benign interaction with teachers and students, encompassing improved emotional and behavioral adjustment [2], academic development [3,4], and subjective well-being [5]. It is worth mentioning that multiple studies have shown that negative teacher–student relationships might contribute to maladaptive behavior patterns, depression, distress, and even suicidal behaviors [6,7,8]. Based on previous literature, teacher–student relationships may favor children’s positive coping in the face of negative physical or psychological consequences.

Coping styles are a set of general strategies used to handle stressful situations when faced with adversity, demonstrated through behavioral and cognitive processes [9]. Different coping styles can be identified based on individual coping characteristics. For instance, coping consists of problem-focused coping (i.e., centered on changing the situation and solving the problem) and emotion-focused coping (i.e., centered on managing negative emotions related to the situation) [10]. Another way to categorize coping is by analyzing whether it is approach-oriented or avoidance-oriented. Specifically, approach-oriented coping involves dealing with reality objectively and diligently, while avoidance-oriented coping involves attempting to ignore stressful events and isolate feelings [11]. Individuals’ attitudes and behaviors in adversity are directly influenced by the type of coping styles they use, which highlights the significance of coping styles in personal growth and mental health. What is more, student development in educational settings is synthetically affected by coping styles. Research suggested that positive coping styles were associated with higher levels of learning motivation [12], academic resilience [13], emotion regulation, and subjective well-being [14] in student populations. However, negative coping styles were predictors of potential mental disorders, which increased the likelihood of maladaptive cognition and problematic behaviors among students [15]. A systematic review showed that the socio-emotional skills training programs for children focused on enhancing their stress management and building adaptive coping skills [16]. Researchers also highlighted the significance of teachers’ support and positive school climate, which helped children overcome academic challenges and deal with peer rejection, ultimately enhancing their problem-focused coping and adaptation [17].

China is a country with a strong emphasis on collectivism, where the importance of harmonious group interactions and the cultivation of interpersonal relationships is highly valued. Hence, in a collectivist culture, fostering good interpersonal relationships becomes crucial for enhancing mental health and facilitating effective coping styles [18,19]. A recent study discovered no clear link between negative coping styles and teacher–student relationships in adolescents [20]. This suggests that as adolescents become more self-aware, their negative coping styles may be more closely tied to internal factors [21]. However, children’s coping strategies could be easily influenced by the adults in their lives [22]. Previous studies have not adequately addressed whether coping styles and teacher–student relationships are influenced by age. We believe that this association cannot be universally applied to children. Past research has offered limited insights into how teacher–student relationships affect coping styles in children. The main purpose of this study was to explore the connection between teacher–student relationships and children’s coping styles, as well as the factors that may influence this correlation. The aim was to uncover the protective factors of children’s health behaviors, which can help mitigate negative coping strategies and enhance their mental well-being.

1.1. The Relationship between Teacher–Student Relationships and Coping Styles

The coping styles one adopts are determined by the type of events they are facing. In China, coping styles are classified into two categories: active coping (e.g., making positive changes) and passive coping (e.g., illusion and negative venting behaviors) [23]. Research has indicated that adults who use a coping style centered on avoiding reality are at a higher risk for alcohol and substance abuse and have increased levels of depression [24]. Research on children has found similar results regarding the correlation between coping styles and mental well-being. Specifically, negative coping styles were linked to anxiety symptoms and perceptions of chronic social adversity [25,26].

Drawing inspiration from the social bond theory, social relationships have a crucial effect on shaping healthy behaviors in individuals [27]. Research showed that positive teacher–student relationships may encourage students to build positive coping styles that develop effective strategies to deal with boredom in language learning [28]. The interactions between teachers and students can encourage students to cope with challenges actively in their school engagement and learning process [20]. Furthermore, fostering positive teacher–student relationships is essential for students to adapt to the school context and reduce student victimization in schools [29,30,31]. Effective teachers establish supportive and non-judgmental classroom environments, which can meet the psychological and behavioral needs of students with emotional or behavioral disorders and ultimately enhance their personal dispositions and abilities [32]. On the other hand, high-conflict teacher–student relationships put children at risk for adverse life events and negative outcomes, including behavioral disorders. In this sense, teacher–student relationships might positively influence coping styles in children.

Hypothesis 1.

Teacher–student relationships significantly and positively predict coping styles in children.

1.2. The Mediating Effect of Peer Relationships

Peer relationships refer to the interpersonal connections between individuals who are at a similar stage of psychological development [33]. As peer relationship research advances, there has been extensive exploration into the connection between peer relationships and psychopathology. Positive peer relationships are crucial for healthy child development, including benefits such as social support, exercise adherence, and academic achievement [34]. Conversely, negative peer relationships were linked to many adverse outcomes, including family victimization, mental illness, and involvement in criminal activities [35]. Research showed that overweight children were prone to negative peer relationships and mental health conditions due to peer problems. The correlation between overweight and mental health issues was largely affected by the existence of peer problems [36].

Based on self-determination theory, individuals tend to improve their mental well-being when the three inherent psychological needs, including relatedness, autonomy, and competence, are fulfilled [37]. Specifically, the fulfillment of relatedness is primarily demonstrated through the growth of interpersonal connections, specifically encompassing the bonds between parents and children, teachers and students, as well as peers. As a positive interpersonal factor, positive peer relationships might also promote children’s coping styles in communication. A recent systematic review has reported that peer relationships can positively influence the way young people cope [38]. Furthermore, prior research also showed that teacher–student relationships and parent–child interactions were positively correlated with student’s peer relationships [39,40]. This serves as a reminder that children’s interpersonal relationships with adults, such as teachers, might impact relationships with peers and the development of behavioral patterns [32]. In conclusion, the evidence presented above reinforces the idea proposed in this study that peer relationships might mediate the correlation between teacher–student relationships and children’s coping styles.

Hypothesis 2a.

Teacher–student relationships significantly and positively predict peer relationships in children.

Hypothesis 2b.

Peer relationships significantly and positively predict coping styles in children.

1.3. The Mediating Effect of Psychological Suzhi

Psychological suzhi is based on physiological factors, converting external stimuli into stable, implicit, and beneficial psychological qualities that are closely linked to adaptability and innovative behaviors [41]. The concept originated under the framework of quality education in China [42]. Moreover, psychological suzhi is impacted by both internal and external factors and highlights three main dimensions: cognitive quality, individuality, and adaptability [41]. Cognitive quality, in particular, has a crucial effect on the cognitive process, self-regulation, and constructive responses to challenges. The significance of psychological suzhi is highly emphasized in China, as it is considered crucial for both social harmony and personal success. Prior research suggested that the enhancement of children’s psychological suzhi was conducive to unlocking their potential, shaping character, molding personality, and ultimately enhancing their social adaptability [43]. In addition, studies indicated that psychological suzhi positively predicted Chinese children’s healthy behavior habits [44], classroom peer status [45], and academic achievement [46]. It is noteworthy that psychological suzhi is integrated into various educational practices and personal development programs [43]. Furthermore, the American Handbook of Positive Psychology in Schools emphasized the scientific research on psychological suzhi in China as a part of the research on positive psychology in Chinese schools within the framework of quality education. This also indicates that the international community is taking notice of the research on psychological suzhi in a positive way [47].

Stage–environment fit theory suggests that a supportive environment can encourage positive development [48]. For students, a supportive climate in school is also essential for healthy growth and development [49]. As one of the dimensions of perceived school climate, teacher–student relationships play an active role in mental health. Prior studies showed a positive relationship between teacher–student relationships and psychological suzhi [50,51]. Specifically, good teacher–student relationships might promote the construction of cognitive skills and adaptability among students, resulting in improved psychological suzhi. What is more, individuals apply different coping styles when faced with stressful situations, leading to shifts in physiological, psychological, and behavioral reactions. Psychological suzhi, as a stable and inherent psychological quality, is advantageous for individuals in coping with challenges and hardships. Prior research showed that male adolescents with high psychological suzhi exhibited reduced state anxiety and heart rate responses during the Trier Social Stress Test [52], suggesting that psychological suzhi was a critical factor that encouraged individuals to adopt active coping styles when confronted with acute stress. Furthermore, relevant research also showed that psychological suzhi may be related to the construction of effective coping strategies. Firstly, it serves as a protective shield that weaken the impact of stressful life situations on sleep quality, allowing students to better navigate through stressful situations [53]. Secondly, psychological suzhi acts as a safeguard against social anxiety, which may improve the social function of students through its influence on self-esteem and sense of security [54].

Hypothesis 3a.

Teacher–student relationships significantly and positively predict psychological suzhi in children.

Hypothesis 3b.

Psychological suzhi significantly and positively predicts coping styles in children.

1.4. The Chain Mediating Effect of Peer Relationships and Psychological Suzhi

The quality of interpersonal relations is closely related to an individual’s behavior patterns and psychological characteristics. As one of the critical social relations, peer relationships can affect student’s mental health. High-quality friendships among peers can provide emotional support, competence, and enjoyable social interactions [55]. Conversely, peer rejection led children to report more negative self-perceptions, hindering their adaptive development [55,56]. Negative peer relationships, such as peer victimization, could also result in children and their parents reporting more symptoms of psychopathology, increasing their risk of mental health problems [57]. Prior studies have shown that peer relationships are positively associated with psychological suzhi [58,59]. Specifically, engaging in cooperative activities with peers can help children feel more competent in schoolwork and a sense of belonging, leading to positive self-evaluations of their behaviors. Children with good peer relationships tend to have more psychological resources and satisfaction than those with negative peer relationships, thus enriching their psychological suzhi. Therefore, peer relationships and psychological suzhi might have chain-mediated effects on the relationship between teacher–student relationships and coping styles.

Hypothesis 4.

Peer relationships significantly and positively predict psychological suzhi in children.

1.5. The Present Research

In the field of child development research, interpersonal relationships of children have been a crucial factor in social adjustment and mental health. Despite extensive exploration, most existing research has focused primarily on positive developmental outcomes related to children’s single interpersonal relationships, such as academic achievement. However, there is a notable lack of research on the interactions between different interpersonal relationships in children’s specific environments, particularly with regard to teacher–student relationships. Considering the critical effect of coping styles in facing adversity, the present research aims to fill this gap by investigating the specific mechanisms between teacher–student relationships and children’s coping styles in the school contexts, exploring the chain-mediated effects of peer relationships and psychological suzhi.

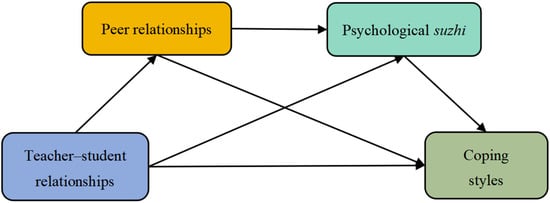

In summary, based on the social bond theory, self-determination theory, stage-environment fit theory, and previous studies, there is a close correlation between teacher–student relationships, peer relationships, psychological suzhi, and coping styles. While previous research has shown connections between the four core variables, there is a lack of studies that specifically create a chain mediation model involving these variables in children samples. Through the construction of the model, we aim to delve into the potential mechanism through which teacher–student relationships impact children’s coping styles. This research will offer a theoretical foundation for enhancing and intervening in children’s coping styles. The chain mediation model is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The assumed model of the chain mediating role of peer relationships and psychological suzhi in the relationship between teacher–student relationships and coping styles.

2. Methods

2.1. Procedures

The data were obtained from a stratified sample of 758 fourth-, fifth-, and sixth-grade children in China (Guangdong Province). The selection criteria included ensuring that the children did not have any psychiatric or neurological disorders, as reported by their teachers in schools. All participants gave informed consent before completing the questionnaires, indicating their voluntary participation and understanding of the purpose, expected duration, and procedures. This study was carried out in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki [60]: we protected the participants’ rights in the research process. The informed consent form we offered ensured that the conventional ethical procedures were clear, including that participants’ information would be kept confidential and the anonymity of reporting was guaranteed. Besides, we followed the ethical guidelines of the American Psychological Association (APA) [61], making sure that researchers in this study program were in good integrity, justice, and responsibility.

Questionnaires were handed out by teachers, and participants were required to complete the demographic information with paper and pen in 25 min, along with the following questionnaires: (1) The Simplified Coping Style Scale [23]; (2) Teacher–Student Relationship Scale and Classmate Relationship Scale [62]; and (3) Simplified Version of the Psychological Suzhi Scale [63]. Participants completed the self-report questionnaires in a quiet classroom within 25 min. The research protocol received approval from the medical ethics committee at Guangzhou Medical University. After excluding 70 samples that did not meet the statistical criteria and had missing data, we proceeded with the data analysis, with an effective recovery rate of 90.8%.

2.2. Participants

The final participant pool comprised 360 boys (52.3%), with an average age of 10.95 years (SD = 0.94), and 328 girls (47.7%), with an average age of 11.02 years (SD = 0.83). This sample included 236 fourth-grade students, 221 fifth-grade students, and 231 sixth-grade students. In addition, there were 153 only children and 535 non-only children. Further exploring the demographic profile in this study, we found a predominance of non-only children in the sample, which may be attributed to the relaxation of China’s birth policies since 2013. It is of concern that China’s only children reported lower levels of psychological distress compared to their peers with siblings [64]. Hence, this variable might be a significant factor influencing children’s mental development, and our research would also focus on this variable.

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Coping Styles

The Simplified Coping Style Scale was used to measure coping styles in our study [23]. This scale consists of 20 items on a four-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (never adopted) to 3 (often adopted). The scale is split into two subscales: positive and negative coping styles. The positive coping style subscale mainly measures features of active coping, such as “talking to someone about inner troubles” and “asking someone for possible advice” when experiencing adversity. The negative coping style subscale measures features of passive coping, including “escaping difficulties” and “waiting without purpose or significance” when facing adversity. The coping tendency score is calculated by subtracting the mean of negative coping styles from the mean of positive coping styles, with a score above 0 indicating a tendency toward active coping and a score below 0 indicating a tendency toward passive coping. In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.904, the measurement model fit indices were as follows: χ2/df = 5.100, RMSEA = 0.077, SRMR = 0.012, CFI = 0.996, and TLI = 0.982, and the scale had good structural validity.

2.3.2. Teacher–Student Relationships

The Teacher–Student Relationship Scale was a subscale of the “My Class Scale”, which was a well-established scale in China [62]. This scale is composed of eight items and uses a five-point Likert format, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The instrument is designed to measure the quality of the relationship between teachers and students. It includes items like “classroom teacher cares about classmates” and “the classroom teacher takes into account the self-esteem of students”, focusing on the interactions between teachers and students. Participants with higher scale scores reported better teacher–student relationships. In this study, the scale demonstrated a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.927; the measurement model fit indices were as follows: χ2/df = 3.442, RMSEA = 0.060, SRMR = 0.020, CFI = 0.991, and TLI = 0.979, and this scale had good structural validity.

2.3.3. Peer Relationships

Peer relationship was measured by the Classmate Relationship Scale for elementary school students [62]. This scale is composed of eight items and uses a five-point Likert format, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The instrument is designed to measure the quality of peer relationships. It includes items like “classmates provide support and encouragement to one another” and “peers can speak truthfully to others”, focusing on the interactions with peers. Participants with higher scale scores reported better peer relationships. In this study, the scale demonstrated a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.769; the measurement model fit indices were as follows: χ2/df = 2.798, RMSEA = 0.051, SRMR = 0.031, CFI = 0.979, and TLI = 0.966, and this scale had good structural validity.

2.3.4. Psychological Suzhi

Psychological suzhi was assessed using the simplified version of the Psychological Suzhi Scale. The scale was created to measure positive psychological characteristics, which contribute to the successful adaptation of Chinese students to the school context [63]. This scale is composed of 27 items and uses a five-point Likert format, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The scale is split into three subscales: cognitive quality, personality quality, and adaptability. Among them, cognitive quality includes metacognitive awareness, planning, and monitoring; personality quality includes confidence, self-esteem, responsibility, and optimism; adaptability includes emotional adaptation, interpersonal adaptation, school adaptation, and frustration tolerance. Each dimension has nine items. Higher scores on the scale indicate higher levels of psychological suzhi. In this study, the scale demonstrated a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.945; the measurement model fit indices were as follows: χ2/df = 3.421, RMSEA = 0.059, SRMR = 0.016, CFI = 0.992, and TLI = 0.981, and this scale had good structural validity.

2.4. Data Analysis

We utilized IBM SPSS 26.0 and Amos 26.0 software to analyze data: (1) the scale’s reliability and validity in this study were assessed using Cronbach’s coefficients and the fitted model indicators; (2) we computed means, standard deviations, and Pearson’s correlation coefficients for assessing the levels of teacher–student relationships, coping styles, peer relationships, and psychological suzhi in Chinese children; (3) the variables of gender, age, and only child status were analyzed in this study, as it was reported that gender, age, and only child status were related to the relationships and coping styles of individuals [65,66,67]; (4) the data was standardized using the Z standardization method in SPSS 26.0 software, which involved standardizing each variable by subtracting the mean and dividing by the standard deviation. In this study, the mediation effect was analyzed using Model 6 in the SPSS PROCESS macro version 3.3 created by Hayes [68]. First, regression analyses explored the relationships between each variable, as well as the association indices in the analyses. Besides, the significance of the mediation effect was tested using the bias-corrected percentile bootstrap method. Harman’s single-factor test can reduce the bias effect caused by the common method [69]. The findings revealed that nine factors had eigenvalues exceeding 1, with the first factor explaining 30.69% of the variance, falling below the 40% critical value criterion. It suggested that no significant common method bias was detected in this study.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics, Correlation Analysis, and Analysis of Variance of Variables

Descriptive analyses showed that the mean value of the scores of coping styles was greater than 0, which indicated that the investigated group of children tended to use positive coping styles. Correlation analyses showed that teacher–student relationships were positively correlated with coping styles, peer relationships, and psychological suzhi (all p < 0.01), with correlation coefficients r ranging from 0.423 to 0.655. Besides, significant positive correlations were noted between the three key variables of coping styles, peer relationships, and psychological suzhi (all p < 0.01), with correlation coefficients r ranging from 0.362 to 0.551. The correlation analysis provided support for testing the hypothesis model and conducting mediation analysis (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Pearson correlation coefficient.

To explore the potential impact of demographic factors (gender, grade, only child status) on teacher–student relationships, peer relationships, psychological suzhi, and coping styles, we performed independent samples t-tests and ANOVA (see Table 2). Our findings revealed no significant difference between children based on gender, grade, and only child status in terms of teacher–student relationships, peer relationships, and coping styles (all p > 0.05). This suggested that gender, grade, and only child status did not have a differential impact on teacher–student relationships, peer relationships, and coping styles in children. However, we did observe a statistically significant difference (all p < 0.05) in psychological suzhi scores between boys and girls, as well as between only children and non-only children. This indicated that gender and only child status might have impacts on psychological suzhi in children, providing a basis for further regression analysis.

Table 2.

Scale scores for different demographic characteristics of 688 students.

3.2. Examining the Mediation Model

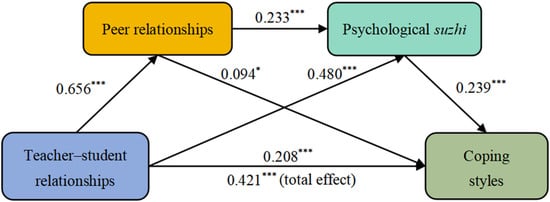

In this study, we utilized the PROCESS macro version 3.3 for SPSS and selected model 6 to analyze the data. The study investigated the impact of teacher–student relationships on children’s coping styles and considered the mediating effects of peer relationships and psychological suzhi, while controlling for gender, grade, and only child status. The findings of regression analyses (see Table 3 and Figure 2) revealed that teacher–student relationships positively predicted coping styles (β = 0.421, t = 12.144, p < 0.001), which showed the total effect of teacher–student relationships on coping styles. Secondly, teacher–student relationships positively predicted peer relationships (β = 0.656, t = 22.713, p < 0.001). Besides, teacher–student relationships (β = 0.480, t = 12.602, p < 0.001) and peer relationships (β = 0.233, t = 6.114, p < 0.001) positively predicted psychological suzhi. Lastly, when all variables were considered together, the effects of three variables on coping styles could be observed simultaneously. The result showed that teacher–student relationships significantly predicted children’s coping styles (β = 0.208, t = 4.192, p < 0.001), which showed the direct effect of teacher–student relationships on coping styles. Moreover, peer relationships (β = 0.094, t = 2.052, p < 0.05) and psychological suzhi (β = 0.239, t = 5.309, p < 0.001) also significantly predicted coping styles. In this regression analysis, the coefficient of determination (R2) was 0.227. Therefore, Hypotheses 1, 2a, 2b, 3a, 3b, and 4 of this study were confirmed.

Table 3.

Regression analyses of chain mediation effects of peer relationships and psychological suzhi.

Figure 2.

A mediating model of teacher–student relationships affecting coping styles. * p < 0.05, *** p < 0.001.

We tested a mediation model using the percentile Bootstrap method (repeated sampling 5000 times) to gain a better understanding of the chain-mediated effects of peer relationships and psychological suzhi in our study (see Table 4). If the 95% confidence interval does not encompass zero, the impact of this pathway is considered significant. The results of the total indirect effects of peer relationships and psychological suzhi revealed that the 95% confidence intervals did not encompass zero (BootLLCI = 0.140, BootULCI = 0.287). This indicated that peer relationships and psychological suzhi played a mediating role in the relationships between teacher–student relationships and coping styles, with a total indirect effect size of 0.213. Further analyses indicated that the total indirect effect was composed of three mediating pathways: (1) teacher–student relationships → peer relationships → coping styles, with 95% confidence intervals for this pathway that did not encompass zero (BootLLCI = 0.002, BootULCI = 0.120), manifesting a significant indirect effect with an effect size of 0.062; (2) teacher–student relationships → psychological suzhi → coping styles, with 95% confidence interval for this pathway that did not encompass zero (BootLLCI = 0.070, BootULCI = 0.164), manifesting a significant indirect effect with an effect size of 0.115; (3) teacher–student relationships → peer relationships → psychological suzhi → coping styles, with 95% confidence interval for this pathway that did not encompass zero (BootLLCI = 0.018, BootULCI = 0.060), manifesting a significant indirect effect with an effect size of 0.036. Moreover, the 95% confidence intervals for the direct effects of teacher–student relationships and coping styles did not encompass zero (BootLLCI = 0.111, BootULCI = 0.306), and was with a direct effect size of 0.208. In terms of effect size, the chain-mediated effect in this study was weak. The 95% confidence intervals for the aggregate effect did not encompass zero (BootLLCI = 0.353, BootULCI = 0.489), and the aggregate effect size was 0.421. In conclusion, the results showed that teacher–student relationships could positively affect children’s coping styles. Peer relationships and psychological suzhi partially mediated the effects of teacher–student relationships on children’s coping styles. What is more, peer relationships and psychological suzhi had chain mediating effects of teacher–student relationships and coping styles in children.

Table 4.

Bias-corrected bootstrap test on mediating effects.

4. Discussion

To explore the intrinsic mechanism of teacher–student relationships affecting children’s coping styles, this study constructed a chain mediation model mediated by peer relationships and psychological suzhi. Moreover, the study also provided an empirical basis for improving children’s coping styles and promoting their mental health and future development.

The results of our study show that teacher–student relationships have a significant and positive effect on children’s coping styles, which confirms Hypothesis 1 of this study. Research has demonstrated that coping styles have beneficial impacts on alleviating mental health symptoms [70]. Conversely, negative coping styles have been identified as a significant factor in mental disorders, such as depression. This highlights the importance of providing behavioral and mental health support to school-aged children and adolescents. Positive teacher–student relationships might improve attachment relationship quality and objective self-perceptions [31], while perceived conflict, harassment, and other negative aspects of teacher–student relationships can contribute to heightened emotional and behavioral problems [71,72]. Moreover, when there is a negative relationship between teachers and students, such as conflicts between them, it can lead to an improved risk of depression. It is of concern that the negative impact of teacher–student conflict outweighed the benefits of teacher–student warmth in this relationship [73]. Recent research has suggested that negative teacher–student interactions can lead to strained relationships and more oppositional behaviors [74]. Therefore, we believe that reducing teacher–student conflict needs to be given special attention in cultivating positive teacher–student relationships, which may reduce the occurrence of children’s negative feelings and bad behaviors. The results showed that Chinese children tended to adopt positive coping styles. Our study supports previous findings that strong teacher–student relationships not only benefit children in shaping healthier psychological and behavioral patterns but also promote adaptive coping when facing adversity in the school context, especially the positive coping styles of children.

The study results indicate that teacher–student relationships positively predict peer relationships, and, in turn, peer relationships positively predict coping styles; peer relationships have a mediating role in the relationships between teacher–student relationships and children’s coping styles. This finding confirms Hypotheses 2a and 2b of this study. One potential explanation for this finding is that positive teacher–student relationships tend to facilitate effective attainment of greater peer liking and acceptance, which may also strengthen children’s psychological suzhi [75]. From another perspective, children may also be more inclined to form friendships with peers who have good relationships with their teachers, reflecting the characteristics of developing peer relationships among children. Children who perceived harmonious teacher–student relationships tended to report more prosocial behaviors, which allowed them to better integrate into student groups [76]. On the contrary, studies have found that adolescents in severely antisocial peer groups tended to have more risky behaviors [77]. Negative peer relationships were also associated with substance use as well as externalizing symptoms in adolescents [78]. In addition, self-determination theory emphasizes that the satisfaction of relatedness can improve mental health and decrease the risk of mental illness. While research has demonstrated the significance of relationships with parents, teachers, and peers, surprisingly limited research has explored the collective impact of these relationships [32,33]. This study suggests that teacher–student relationships may promote positive coping with adversity in children through peer relationships, thus establishing positive coping styles. We provide empirical support for the link between the need for relatedness and personal development in self-determination theory, clarifying the importance of relationships with teachers and peers in influencing children’s coping styles.

Moreover, in the Chinese cultural context, the study results indicate that teacher–student relationships positively predict psychological suzhi, and, in turn, psychological suzhi positively predict coping styles; psychological suzhi has a mediating role in the relationships between teacher–student relationships and children’s coping styles. This finding confirms Hypotheses 3a and 3b of this study. A previous study has shown that the relationship between teachers and students is a significant factor in determining the level of closeness, social interactions, and academic achievement [79]. Teachers play a crucial role in providing social support to children, which, in turn, has a beneficial effect on their mental well-being and future growth. As an endogenous factor for mental health, psychological suzhi also plays a critical role in shaping health behaviors and reducing negative behaviors in children [80,81]. Correspondingly, children who received teacher support are more inclined to have benign interaction with the teacher, and it may improve their psychological suzhi. Due to the improvement of psychological suzhi, children might tend to build a more positive coping style. Besides, we found that boys have higher psychological suzhi than girls, while the psychological suzhi of non-only children is higher than that of only children. This may be due to the fact that boys have internalized the idea of masculinity and express higher confidence [82], which will improve their personality quality. Moreover, different family compositions and sizes shape various family interaction patterns. For non-only children, the presence of siblings provides them with more opportunities to interact with peers and demonstrates higher agreeableness [83], which may help enhance their adaptability.

The results also indicate that peer relationships have a significant and positive effect on psychological suzhi, which confirms Hypothesis 4 of this study. Moreover, the connection between teacher–student relationships and coping styles is sequentially mediated by peer relationships and psychological suzhi. When children perceive harmonious teacher–student relationships, they might develop good interpersonal relationships and inner qualities [84]. Besides, Pan and colleagues [59] found that peer attachment has a notable and favorable impact on psychological suzhi. Specifically, children with negative peer relationships may have lower peer liking and psychological suzhi than those with positive peer relationships. Thus, fostering an inclusive peer environment might facilitate children’s peer experience and psychological suzhi, thereby encouraging positive coping styles. This indicates that when teacher–student relationships lack warmth, school leaders can introduce initiatives to improve these relationships, which will elevate the school’s education quality [85].

5. Implications, Limitations, and Future Research Directions

The results of the study have theoretical significance and practical value for promoting coping styles in children. From a theoretical perspective, the findings suggest that teachers have a multifaceted influence on children. In addition to their role in education, teachers also play a critical part in encouraging children’s emotional, behavioral, and social development. By building good relationships with students and creating a supportive environment, teachers contribute to children’s psychological suzhi and facilitate them to form healthy peer relationships and adaptive coping styles. In turn, these positive qualities also contribute to children’s resilience and success in social, academic, and mental aspects.

Moreover, to enhance children’s coping styles, the following suggestions are proposed: First, the formation of coping styles is crucial during childhood. Thus, attention should be paid to children who perceive the teacher–student relationships as negative, which may imply that their coping styles are more negative than those of their peers and report more psychopathology symptoms. Second, in designing programs to improve positive coping, the significance of social relationships must be emphasized, and this includes fostering teacher–student and peer relationships. When interviewing children with negative coping styles, school counselors can encourage these children to participate in classroom activities, which may help them gain positive interpersonal relationships from these activities. Moreover, psychology teachers can organize and conduct consistent psychological suzhi training sessions to boost children’s psychological suzhi, potentially leading to an enhancement in their coping styles. Finally, psychological training can be carried out in schools, which aims to teach children to cultivate adaptive coping styles and resilience and enhance the ability to address problems, thereby improving their mental health.

The findings hold great importance for programs designed to improve children’s coping styles. While there are some highlights, the present study had several limitations that required further interpretation. First, due to the cross-sectional design of our research, we were unable to establish a causal relationship between the study variables. Second, although this study found that the chain-mediated pathway of peer relationships and psychological suzhi is significant, the mediating effects and the chain mediating effect were comparatively weak in the study. Understood in terms of regression analysis, the results of the coefficient of determination also reflect the presence of other important variables in the impact of teacher–student relationships on children’s coping styles [86]. Third, because all data are based on self-reporting by children, our results may be affected by biases due to social desirability. This study included only Chinese children; generalizing the findings to other cultures or age groups requires caution. Therefore, future experimental and longitudinal studies should further examine the findings of this study by delving more deeply into the mechanisms of influence among the variables investigated. Moreover, we will also explore the critical factors involved between teacher–student relationships and children’s coping styles, which are worth further exploration in future research. Although no deviation from common methods was observed, it is recommended that research utilizes different types of data collection methodologies in the future, such as combining self-reports with reports from others (e.g., teachers and parents), to enhance the reliability of the conclusions. Further studies can investigate how interpersonal relationships impact children’s coping styles in different groups and cultural contexts.

6. Conclusions

This study investigated how teacher–student relationships impact children’s coping styles, specifically looking at how peer relationships and psychological suzhi mediate this relationship. Using a chain mediation model, the study reached the following conclusions: (1) Teacher–student relationships, as extrinsic factors, can positively predict children’s coping styles, peer relationships, and psychological suzhi. (2) Peer relationships, as extrinsic factors, can positively impact children’s coping styles and psychological suzhi. (3) Psychological suzhi, as an intrinsic quality, also plays a positive role in shaping coping styles in children. (4) Peer relationships and psychological suzhi play mediating roles in the link between teacher–student relationships and children’s coping styles, operating through three different pathways: the mediation of peer relationships, the mediation of psychological suzhi, and the chain mediation of peer relationships and psychological suzhi.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.W. and C.Y.; data curation, S.S.; formal analysis, S.S.; funding acquisition, S.G.; investigation, C.Y., X.Y. and N.B.; methodology, X.W., C.Y. and S.G.; software, S.S.; validation, N.B.; visualization, X.Y.; writing—original draft, X.W.; writing—review and editing, S.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Guangzhou Municipal Education Bureau Youth Talent Research Project (grant number 202235414), the Guangzhou Science and Technology Plan Project (grant number 202206060004), the Research Capacity Enhancement Program Project of Guangzhou Medical University (grant number 02-410-2405118), the Special Funding for the Cultivation of Guangdong College Students’ Scientific and Technological Innovation (“Climbing Program”) (grant number pdjh2023b0437), and the 2023 College Student Innovation and Entrepreneurship Training Program of Guangzhou Medical University (grant number S202310570047).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the medical ethics committee of Guangzhou Medical University (protocol code GMU202210, approval date: 24 October 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Birch, S.H.; Ladd, G.W. Children’s interpersonal behaviors and the teacher-child relationship. Dev. Psychol. 1998, 34, 934–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.T.; Brinkworth, M.; Eccles, J. Moderating effects of teacher-student relationship in adolescent trajectories of emotional and behavioral adjustment. Dev. Psychol. 2013, 49, 690–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zee, M.; Rudasill, K.M.; Bosman, R.J. A cross-lagged study of students’ motivation, academic achievement, and relationships with teachers from kindergarten to 6th grade. J. Educ. Psychol. 2021, 113, 1208–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, E.A.; Rickert, N.P.; Vollet, J.W.; Kindermann, T.A. The complex social ecology of academic development: A bioecological framework and illustration examining the collective effects of parents, teachers, and peers on student engagement. Educ. Psychol. 2022, 57, 87–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamizo-Nieto, M.T.; Arrivillaga, C.; Rey, L.; Extremera, N. The Role of Emotional Intelligence, the Teacher-Student Relationship, and Flourishing on Academic Performance in Adolescents: A Moderated Mediation Study. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 695067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halladay, J.; Bennett, K.; Weist, M.; Boyle, M.; Manion, I.; Campo, M.; Georgiades, K. Teacher-student relationships and mental health help seeking behaviors among elementary and secondary students in Ontario Canada. J. Sch. Psychol. 2020, 81, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roorda, D.L.; Koomen, H.M.Y. Student-Teacher Relationships and Students’ Externalizing and Internalizing Behaviors: A Cross-Lagged Study in Secondary Education. Child. Dev. 2021, 92, 174–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torsheim, T.; Wold, B. School-Related Stress, School Support, and Somatic Complaints: A General Population Study. J. Adolesc. Res. 2001, 16, 293–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Chen, A.; Quan, S. The effect of perfectionism on school burnout among adolescence: The mediator of self-esteem and coping style. Pers. Individ. Dif. 2016, 88, 202–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folkman, S.; Moskowitz, J.T. Coping: Pitfalls and promise. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2004, 55, 745–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compas, B.E.; Worsham, N.L.; Ey, S. Conceptual and developmental issues in children’s coping with stress. In Stress And Coping in Child Health; Guilford: New York, NY, USA, 1992; pp. 7–24. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, X.; Peng, Q.; Wu, S.; Li, Y.; Dong, W.; Tang, H.; Lu, G.; Chen, C. Perceived parenting style and Chinese nursing undergraduates’ learning motivation: The chain mediating roles of self-efficacy and positive coping style. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2023, 68, 103607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janssen, T.W.P.; van Atteveldt, N. Coping styles mediate the relation between mindset and academic resilience in adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic: A randomized controlled trial. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 6060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Ji, L.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, C.; Ge, C.; Zhang, X. How to Improve the Well-Being of Youths: An Exploratory Study of the Relationships Among Coping Style, Emotion Regulation, and Subjective Well-Being Using the Random Forest Classification and Structural Equation Modeling. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 637712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Luo, Y.; Zhao, J.; Cui, Y.; Chen, H. Peer Teasing and Restrained Eating among Chinese College Students: The Chain Mediating Role of Negative Coping Styles and Negative Physical Self. Nutrients 2024, 16, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenwick-Smith, A.; Dahlberg, E.E.; Thompson, S.C. Systematic review of resilience-enhancing, universal, primary school-based mental health promotion programs. BMC. Psychol. 2018, 6, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolchik, S.A.; Sandler, I.N. (Eds.) Handbook of Children’s Coping: Linking Theory and Intervention; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1997; pp. 387–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, W.; Chen, M.; Wang, T.; Sun, S. Coping strategies in Chinese social context. Asian. J. Soc. Psychol. 2008, 11, 150–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, W.; Feng, M.; Yu, H.; Hou, Y. The Impact of the Chinese Thinking Style of Relations on Mental Health: The Mediating Role of Coping Styles. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, L.; Kong, F.; Cui, L.; Feng, N.; Wang, X. Teacher–student relationships and adolescents’ classroom incivility: A moderated mediation model of moral disengagement and negative coping style. Psychol. Sch. 2024, 61, 496–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Zhao, J. How rumination influences meaning in life among Chinese high school students: The mediating effects of perceived chronic social adversity and coping style. Front. Public. Health. 2023, 11, 1280961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesmore, A.A.; Weiler, L.M.; Taussig, H.N. Mentoring Relationship Quality and Maltreated Children’s Coping. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2017, 60, 229–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y. A preliminary study on the reliability and validity of the Short Coping Style Scale. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 1998, 6, 114–115. [Google Scholar]

- Tokumitsu, K.; Sugawara, N.; Okayasu, H.; Kawamata, Y.; Shinozaki, M.; Sato, Y.; Sato, A.; Uchibori, Y.; Komatsu, T.; Yasui-Furukori, N.; et al. The relationship of stress coping styles on substance use, depressive symptoms, and personality traits of nurses in higher education institution. Neuropsychopharmacol. Rep. 2023, 43, 482–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.C. Coping styles and the developmental trajectories of anxiety symptoms in children during transition into early adolescence. Br. J. Psychol, 2024; advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, F.; Duan, R.; Huang, B.; Wang, Q. Psychological resilience and cognitive reappraisal mediate the effects of coping style on the mental health of children. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1110642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, C.O.; Mueller, C.E. School delinquency and social bond factors: Exploring gendered differences among a national sample of 10th graders. Psychol. Sch. 2013, 50, 116–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. EFL learners’ boredom coping strategies: The role of teacher-student rapport and support. BMC. Psychol. 2023, 11, 397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, J.A. Contributions of teacher–child relationships to positive school adjustment during elementary school. J. Sch. Psychol. 2016, 44, 211–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marengo, D.; Fabris, M.A.; Prino, L.E.; Settanni, M.; Longobardi, C. Student-teacher conflict moderates the link between students’ social status in the classroom and involvement in bullying behaviors and exposure to peer victimization. J. Adolesc. 2021, 87, 86–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Rodríguez, L.; Redín, C.I.; Abaitua, C.R. Teacher-student attachment relationship, variables associated, and measurement: A systematic review. Educ. Res. Rev. 2023, 38, 100488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leggio, J.C.; Terras, K.L. An Investigation of the Qualities, Knowledge, and Skills of Effective Teachers for Students with Emotional/Behavioral Disorders: The Teacher Perspective. J. Spec. Educ. 2019, 8, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, K.H.; Bukowski, W.M.; Parker, J.G. Peer Interactions, Relationships, and Groups. In Handbook of Child Psychology: Social, Emotional, And Personality Development; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016; pp. 571–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endedijk, H.M.; Breeman, L.D.; van Lissa, C.J.; Hendrickx, M.M.H.G.; den Boer, L.; Mainhard, T. The teacher’s invisible hand: A meta-analysis of the relevance of teacher—Student relationship quality for peer relationships and the contribution of student behavior. Rev. Educ. Res. 2022, 92, 370–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukowski, W.M.; Adams, R. Peer relationships and psychopathology: Markers, moderators, mediators, mechanisms, and meanings. J. Clin. Child. Adolesc. Psychol. 2005, 34, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hestetun, I.; Svendsen, M.V.; Oellingrath, I.M. Associations between overweight, peer problems, and mental health in 12-13-year-old Norwegian children. Eur. Child. Adoles. Psy. 2015, 24, 319–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haddow, S.; Taylor, E.P.; Schwannauer, M. Positive peer relationships, coping and resilience in young people in alternative care: A systematic review. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2021, 122, 105861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxer, K.; Schnell, J.; Mori, J.; Hascher, T. The role of teacher–student relationships and student–student relationships for secondary school students’ well-being in Switzerland. Int. J. Educ. Res. Open. 2024, 6, 100318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, P.; Dong, J.; Liu, J.; Wen, H.; Wang, Z. The relationship between parent-child relationship and peer victimization: A multiple mediation model through peer relationship and depression. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1170891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.J.; Wang, J.L.; Yu, L. (Eds.) Methods and Implementary Strategies on Cultivating Students’ Psychological Suzhi; Nova Science Publishers: Hauppauge, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 1–46. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, D.J.; Feng, Z.Z.; Guo, C.; Chen, X. Problems on research of students’ mental quality. J. Southwest. Univ. 2000, 26, 56–62. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, D.J.; Wang, X. An analysis of the relationship between mental health and psychological suzhi: From the perspective of connotation and structure. J. Southwest. Univ. 2012, 38, 69–74. [Google Scholar]

- Mo, X.; Wang, Z.; Shao, J. Parent-child attachment and good behavior habits among Chinese children: Chain mediation effect of parental involvement and psychological Suzhi. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0241586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.M.; Xiao, X.; Xiong, S.; Guo, C.; Cheng, G. Effects of parental educational involvement on classroom peer status among Chinese primary school students: A moderated mediation model of psychological Suzhi and family socioeconomic status. J. Can. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 2020, 111, 104881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Zhao, Z.; Zhang, D. Cross-lagged relations between psychological suzhi and academic achievement. Curr. Psychol. 2020, 39, 1496–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, L.; Li, Z.; Chen, H.; Han, M.; Wang, D.; Huang, S.; Zheng, X. Applications of positive psychology to schools in China. In Handbook of Positive Psychology in Schools, 2nd ed.; Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group: Abingdon, UK, 2014; pp. 433–449. [Google Scholar]

- Eccles, J.S.; Midgley, C.; Wigfield, A.; Buchanan, C.M.; Reuman, D.; Flanagan, C.; Iver, D.M. Development during adolescence: The impact of stage-environment fit on young adolescents’ experiences in schools and in families. Am. Psychol. 1993, 48, 90–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voight, A.; Nation, M. Practices for improving secondary school climate: A systematic review of the research literature. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2016, 58, 174–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, Q.; Yang, C.; Teng, Z.; Furlong, M.J.; Pan, Y.; Guo, C.; Zhang, D. Longitudinal association between school climate and depressive symptoms: The mediating role of psychological suzhi. Sch. Psychol. 2020, 35, 267–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, H.A. Conceptualizing the Role and Influence of Student-Teacher Relationships on Children’s Social and Cognitive Development. Educ. Psychol. 2003, 38, 207–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Ding, F.; Zhang, T.; He, H.; Wang, J.; Pan, Y.; Zhang, D. Psychological suzhi moderates state anxiety and heart rate responses to acute stress in male adolescents. Stress. Health 2022, 38, 581–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, Z.; Zhang, D.J. Relationship between stressful life events and sleep quality: The mediating and moderating role of psychological suzhi. Sleep. Med. 2022, 96, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Z.; Zhang, D.J.; Hu, T.; Pan, Y. The relationship between psychological Suzhi and social anxiety among Chinese adolescents: The mediating role of self-esteem and sense of security. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health. 2018, 12, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hay, D.F.; Payne, A.; Chadwick, A. Peer relations in childhood. J. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry 2004, 45, 84–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wible, B. Disruptive classmates, long-term harm. Science 2018, 361, 889–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Haltigan, J.D.; Vaillancourt, T. Joint trajectories of bullying and peer victimization across elementary and middle school and associations with symptoms of psychopathology. Dev. Psychol. 2014, 50, 2426–2436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, A.C.; Zhang, T.J.; Pan, P.L.; Chen, M.F.; Ma, Y.X. The relationship between middle school students’ psychological suzhi and peer relationship: The mediating role of self-esteem. J. Psychol. Sci. 2016, 39, 1290. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, Y.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, D.; Ran, G.; Li, B.; Liu, C.; Liu, G.; Luo, S.; Chen, W. Parental and peer attachment and adolescents’ behaviors: The mediating role of psychological suzhi in a longitudinal study. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2017, 83, 218–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA 2013, 310, 2191–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychological Association. Revision of Ethical Standard 3.04 of the “Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct” (2002, as amended 2010). Am. Psychol. 2016, 71, 900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, G.R. Classroom environment in primary and secondary schools: Structure and measurement. J. Psychol. Sci. 2004, 4, 839–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.G.; Zhang, D.J.; Wu, L.L. Revision and validation of psychological suzhi questionnaire for elementary school students—Based on two-factor model. J. Southwest. Univ. 2017, 43, 127–133. [Google Scholar]

- Falbo, T.; Hooper, S.Y. China’s only children and psychopathology: A quantitative synthesis. Am. J. Orthopsychiatr. 2015, 85, 259–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maccoby, E.E. Gender and relationships. A developmental account. Am. Psychol. 1990, 45, 513–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, A.M.; Kashikar-Zuck, S.; Goldschneider, K.R.; Jones, B.A. Sex and age differences in coping styles among children with chronic pain. J. Pain. Symptom. Manag. 2007, 33, 208–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, Y.; Huang, L.; Si, T.; Wang, N.Q.; Qu, M.; Zhang, X.Y. The role of only-child status in the psychological impact of COVID-19 on mental health of Chinese adolescents. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 282, 316–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis. In A Regression-Based Approach, 2nd ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 10–450. [Google Scholar]

- Livingstone, L.P.; Nelson, D.L.; Barr, S.H. Person–environment fit and creativity: An examination of supply–value and demand–ability versions of fit. J. Manag. 1997, 23, 119–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, H.; Zhang, R.; Li, L.; Yang, L. Coping Style and Resilience Mediate the Effect of Childhood Maltreatment on Mental Health Symptomology. Children 2022, 9, 1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salter, D.; Neelakandan, A.; Wuthrich, V.M. Anxiety and Teacher-Student Relationships in Secondary School: A Systematic Literature Review. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2024. advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ban, J.; Oh, I. Mediating effects of teacher and peer relationships between parental abuse/neglect and emotional/behavioral problems. Child Abuse. Negl. 2016, 61, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivier, E.; Azarnia, P.; Morin, A.J.S.; Houle, S.A.; Dubé, C.; Tracey, D.; Maïano, C. The moderating role of teacher-student relationships on the association between peer victimization and depression in students with intellectual disabilities. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2020, 98, 103572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdebenito, S.; Speyer, L.; Murray, A.L.; Ribeaud, D.; Eisner, M. Associations between Student-Teacher Bonds and Oppositional Behavior Against Teachers in Adolescence: A Longitudinal Analysis from Ages 11 to 15. J. Youth Adolesc. 2022, 51, 1997–2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughes, J.N.; Im, M.H. Teacher-Student Relationship and Peer Disliking and Liking Across Grades 1–4. Child. Dev. 2016, 87, 593–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Longobardi, C.; Settanni, M.; Lin, S.; Fabris, M.A. Student-teacher relationship quality and prosocial behaviour: The mediating role of academic achievement and a positive attitude towards school. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2021, 91, 547–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, D. Peer-relationship patterns and their association with types of child abuse and adolescent risk behaviors among youth at-risk of maltreatment. J. Adolesc. 2020, 80, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, D.; Yoon, M.; Wang, X.; Robinson-Perez, A.A. A developmental cascade model of adolescent peer relationships, substance use, and psychopathological symptoms from child maltreatment. Child Abuse Negl. 2023, 137, 106054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poling, D.V.; Loan, C.L.V.; Garwood, J.D.; Zhang, S.; Riddle, D. Enhancing teacher-student relationship quality: A narrative review of school-based interventions. Educ. Res. Rev. 2022, 37, 100459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Wang, Z. The Effects of Family Functioning and Psychological Suzhi Between School Climate and Problem Behaviors. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, D. Forgiveness as a Mediator between Psychological Suzhi and Prosocial Behavior in Chinese Adolescents. Behav. Sci. 2022, 12, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, T.A. Gender and the influence of evaluations on self-assessments in achievement settings. Psychol. Bull. 1991, 109, 297–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Hou, X.; Wei, D.; Wang, K.; Li, Y.; Qiu, J. Only-child and non-only-child exhibit differences in creativity and agreeableness: Evidence from behavioral and anatomical structural studies. Brain. Imaging Behav. 2017, 11, 493–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, C.D. A framework for motivating teacher-student relationships. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2022, 34, 2061–2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosman, R.J.; Zee, M.; de Jong, P.F.; Koomen, H.M.Y. Using relationship-focused reflection to improve teacher-child relationships and teachers’ student-specific self-efficacy. J. Sch. Psychol. 2021, 87, 28–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, C.J. An effect size primer: A guide for clinicians and researchers. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. 2009, 40, 532–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).