Consumers’ Psychology Regarding Attachment to Social Media and Usage Frequency: A Mediated-Moderated Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- To investigate the effect of consumers’ ASM on their perceived SMMAs;

- (2)

- To observe the moderating effect of consumers’ social media usage frequencies regarding the effect of perceived SMMAs on brand equity and purchase intentions.

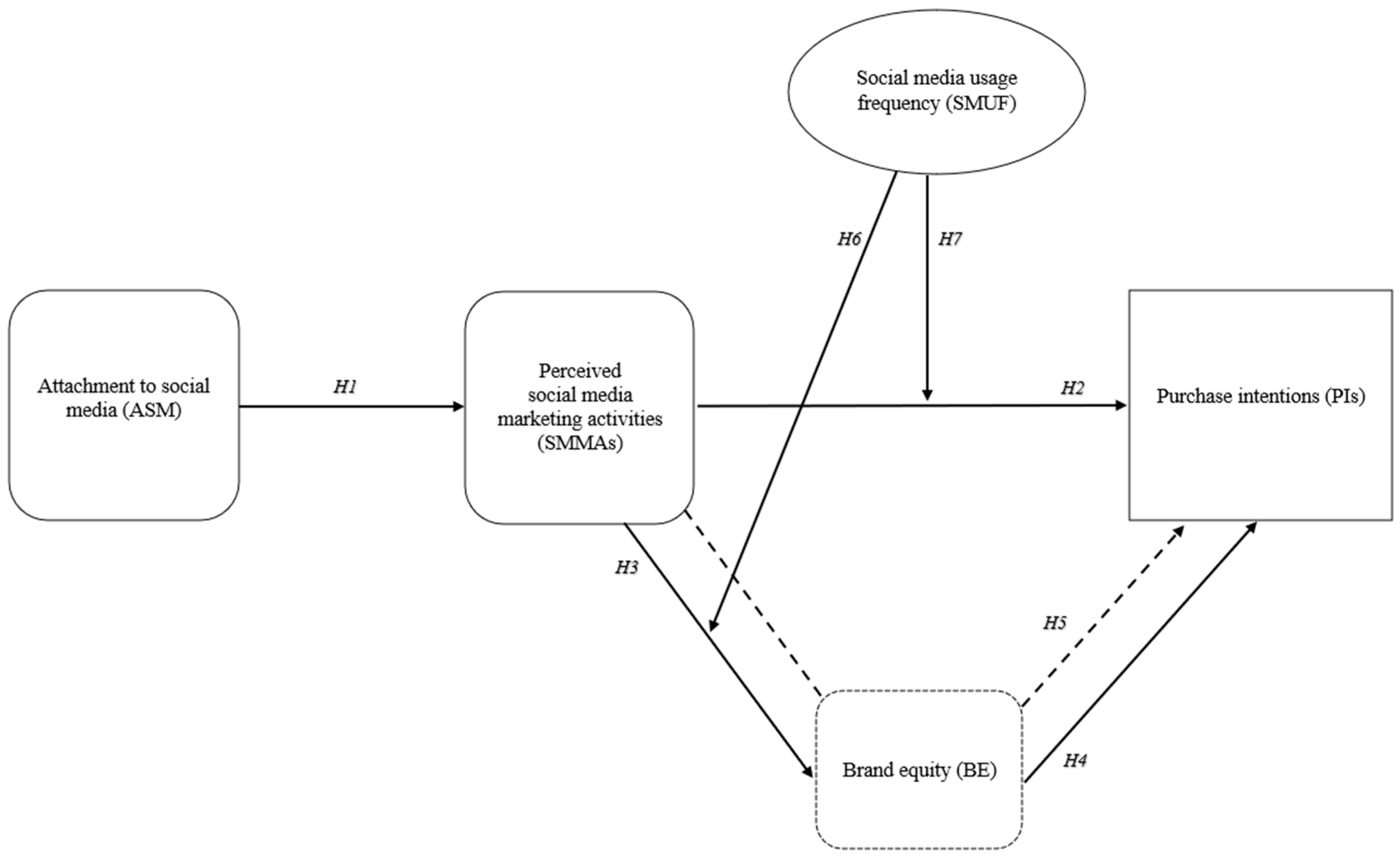

2. Conceptual Framework and Hypotheses

2.1. Attachment to Social Media

2.2. Perceived Social Media Marketing Activities

2.3. Brand Equity

“A set of brand assets and liabilities linked to a brand, its name and symbol, that add to or subtract from the value provided by a product or service to a firm and/or to that firm’s customers”.

2.4. Purchase Intentions

2.5. Direct Effect Hypothesis Development

2.6. Mediating and Moderating Effect Hypothesis Development

3. Methodology

3.1. Sample and Procedure

3.2. Measurement

4. Results

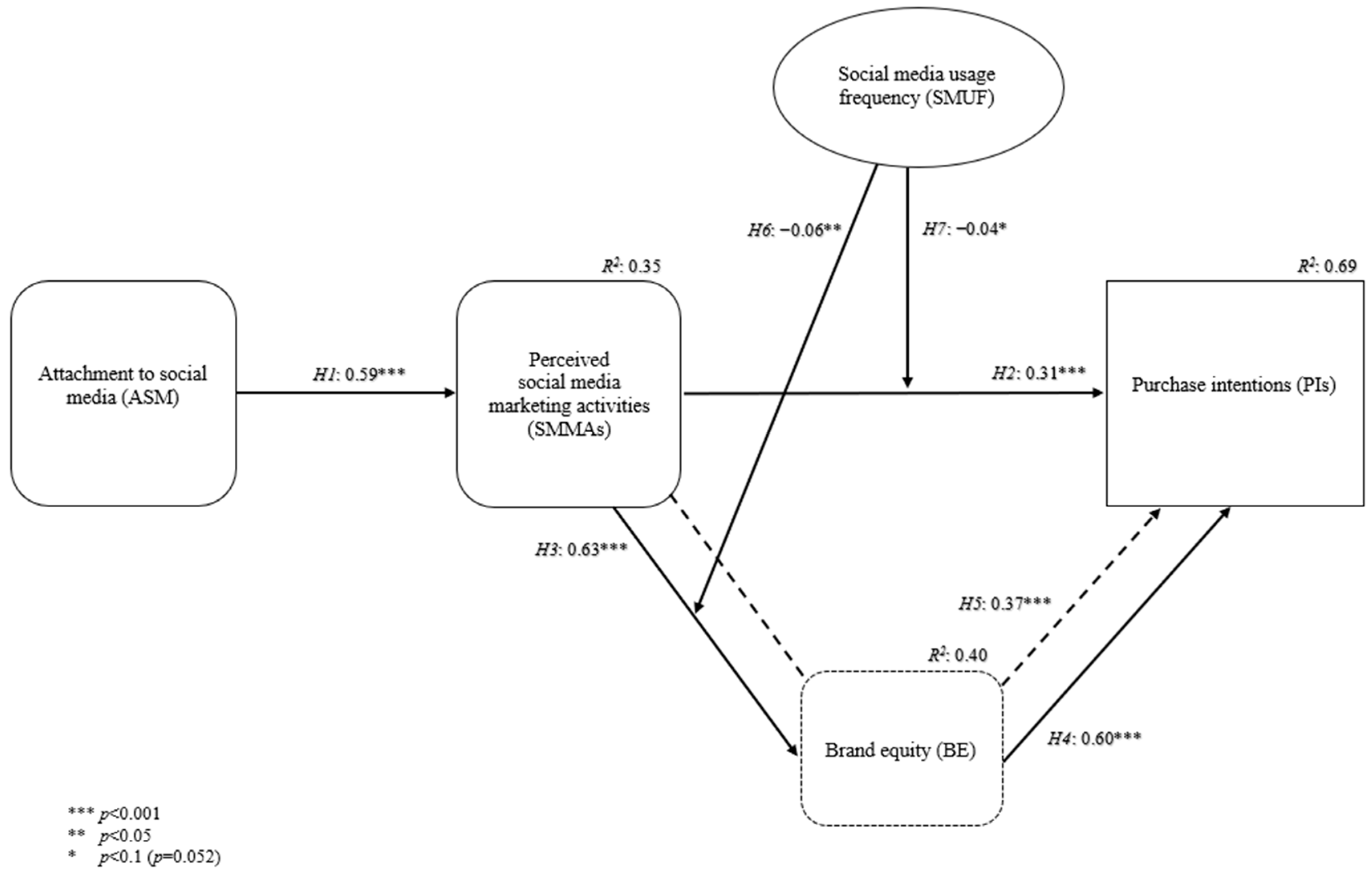

4.1. Testing the Direct Effect Hypotheses

4.2. Results of Mediating and Moderating Effects

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Theoretical Contribution

5.2. Managerial Implications

5.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Construct | Item | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Attachment to social media Dimensions: Connecting Nostalgia Informed Enjoyment Advice Affirmed Enhances my life Influence | CON1: “I use social media to interact with friends”. | VanMeter et al. [25] |

| CON2: “Social media provides a way for me to stay connected to people across distances”. | ||

| CON3: “I use social media because it makes staying in touch with others convenient”. | ||

| CON4: “Social media provides a way for me to keep in touch with others that I care about”. | ||

| NOS1: “Social media allows me to look back at meaningful events, people, and places from my past”. | ||

| NOS2: “Using social media makes me feel nostalgic about things that I have done in the past”. | ||

| NOS3: “Sometimes social media reminds me of warm memories from my past”. | ||

| INF1: “Social media is one of the main ways I get information about major events”. | ||

| INF2: “Social media allows me to stay informed about events and news”. | ||

| INF3: “Social media is one of my primary sources of information about news”. | ||

| ENJ1: “I use social media as a way for me to de-stress after a long day”. | ||

| ENJ2: “I use social media to give myself a break when I’ve been busy”. | ||

| ENJ3: “Social media is an enjoyable way to spend time”. | ||

| ADV1: “I seek advice for upcoming decisions using social media”. | ||

| ADV2: “I get advice about medical questions on social media”. | ||

| ADV3: “If I’m unsure about an upcoming decision I get input from friends on social media”. | ||

| AFF1: “When others comment on my posts I feel affirmed”. | ||

| AFF2: “When people respond to my posts in social media I feel like they care about me”. | ||

| AFF3: “It makes me feel accepted when people comment on my social media posts”. | ||

| EML1: “Social media makes my life a little bit better”. | ||

| EML2: “Social media enhances my life”. | ||

| EML3: “My life is a little richer because of social media”. | ||

| INFL1: “Sometimes I post things just to have a positive effect on other peoples’ moods”. | ||

| INFL2: “I post on social media to brighten other peoples’ day”. | ||

| INFL3: “I post things on social media that I think will be helpful to my friends’ lives”. | ||

| INFL4: “I want to inspire other people with my social media posts”. | ||

| INFL5: “I think it is important to share things on social media so those I care about stay informed”. | ||

| Perceived social media marketing activities Dimensions: Entertainment Interaction Trendiness Customization Word-of-mouth | ENT1: “Using brand X’s social media is fun”. | Kim and Ko [9] |

| ENT2: “Contents shown in brand X’s social media seem interesting”. | ||

| INT1: “Brand X’s social media enables information sharing with others”. | ||

| INT2: “Conversation or opinion exchange with others is possible through brand X’s social media”. | ||

| INT3: “It is easy to deliver my opinion through brand X’s social media”. | ||

| TRE1: “Contents shown in brand X’s social media is the newest information”. | ||

| TRE2: “Using brand X’s social media is very trendy”. | ||

| CUS1: “Brand X’s social media offers customized information search”. | ||

| CUS2: “Brand X’s social media provides customized service”. | ||

| WOM1: “I would like to pass along information on brand, product, or services from brand X’s social media to my friends”. | ||

| WOM2: “I would like to upload contents from brand X’s social media on my blog or micro blog”. | ||

| Brand equity Dimensions: Brand awareness Brand associations Brand loyalty Perceived quality | BAW1: “I can recognize brand X among other competing brands”. | Yoo and Donthu [55] Washburn and Plank [51] |

| BAW2: “I am aware of brand X”. | ||

| BAW3: “I know what brand X looks like”. | ||

| BAS1: “Some characteristics of brand X come to my mind quickly”. | ||

| BAS2: “I can quickly recall the symbol or logo of brand X”. | ||

| BAS3: “I can easily imagine brand X in my mind”. | ||

| BLO1: “I consider myself to be loyal to brand X”. | ||

| BLO2: “Brand X would be my first choice”. | ||

| BLO3: “I will not buy other brands if brand X is available at the store”. | ||

| PQ1: “The likely quality of brand X is extremely high”. | ||

| PQ2: “The likelihood that brand X would be functional is very high”. | ||

| PQ3: “Brand X is of high quality”. | ||

| Purchase intentions | PI1: “I would like to buy brand X”. | Yoo and Donthu [55] Chen and Chang [109] |

| PI2: “I intend to purchase brand X”. | ||

| PI3: “I am willing to purchase brand X in the future”. |

References

- Keller, K.L. Unlocking the Power of Integrated Marketing Communications: How Integrated Is Your IMC Program? J. Advert. 2016, 45, 286–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyftopoulos, S.; Drosatos, G.; Fico, G.; Pecchia, L.; Kaldoudi, E. Analysis of Pharmaceutical Companies’ Social Media Activity during the COVID-19 Pandemic and Its Impact on the Public. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Li, Y. Influence of Strategic Crisis Communication on Public Perceptions during Public Health Crises: Insights from YouTube Chinese Media. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reimann, L.-E.; Binnewies, C.; Ozimek, P.; Loose, S. I Do Not Want to Miss a Thing! Consequences of Employees’ Workplace Fear of Missing Out for ICT Use, Well-Being, and Recovery Experiences. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moslehpour, M.; Ismail, T.; Purba, B.; Wong, W.-K. What Makes GO-JEK Go in Indonesia? The Influences of Social Media Marketing Activities on Purchase Intention. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2022, 17, 89–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rúa-Hidalgo, I.; Galmes-Cerezo, M.; Cristofol-Rodríguez, C.; Aliagas, I. Understanding the Emotional Impact of GIFs on Instagram through Consumer Neuroscience. Behav. Sci. 2021, 11, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.-C.; Hsu, W.-C.J.; Yeh, C.-S.; Lin, Y.-S. A Hybrid Model for Fitness Influencer Competency Evaluation Framework. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godey, B.; Manthiou, A.; Pederzoli, D.; Rokka, J.; Aiello, G.; Donvito, R.; Singh, R. Social Media Marketing Efforts of Luxury Brands: Influence on Brand Equity and Consumer Behavior. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 5833–5841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, A.J.; Ko, E. Do Social Media Marketing Activities Enhance Customer Equity? An Empirical Study of Luxury Fashion Brand. J. Bus. Res. 2012, 65, 1480–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koay, K.Y.; Ong, D.L.T.; Khoo, K.L.; Yeoh, H.J. Perceived Social Media Marketing Activities and Consumer-Based Brand Equity: Testing a Moderated Mediation Model. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2020, 33, 53–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, A.J.; Ko, E. Impacts of Luxury Fashion Brand’s Social Media Marketing on Customer Relationship and Purchase Intention. J. Glob. Fash. Mark. 2010, 1, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, M.; Rahman, Z. Measuring Consumer Perception of Social Media Marketing Activities in E-Commerce Industry: Scale Development & Validation. Telemat. Inform. 2017, 34, 1294–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ural, T.; Yuksel, D. The Mediating Roles of Perceived Customer Equity Drivers between Social Media Marketing Activities and Purchase Intention. Int. J. Econ. Commer. Manag. 2015, 3, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Seo, E.-J.; Park, J.-W. A Study on the Effects of Social Media Marketing Activities on Brand Equity and Customer Response in the Airline Industry. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2018, 66, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, M.; Rahman, Z. The Influence of Social Media Marketing Activities on Customer Loyalty: A Study of e-Commerce Industry. Benchmarking Int. J. 2018, 25, 3882–3905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datareportal. Digital 2024: Turkey. Available online: https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2024-turkey (accessed on 30 July 2024).

- Fournier, S. Consumers and Their Brands: Developing Relationship Theory in Consumer Research. J. Consum. Res. 1998, 24, 343–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, M.; MacInnis, D.J.; Whan Park, C. The Ties That Bind: Measuring the Strength of Consumers’ Emotional Attachments to Brands. J. Consum. Psychol. 2005, 15, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.W.; Macinnis, D.J.; Priester, J.; Eisingerich, A.B.; Iacobucci, D. Brand Attachment and Brand Attitude Strength: Conceptual and Empirical Differentiation of Two Critical Brand Equity Drivers. J. Mark. 2010, 74, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitriu, R.; Guesalaga, R. Consumers’ Social Media Brand Behaviors: Uncovering Underlying Motivators and Deriving Meaningful Consumer Segments. Psychol. Mark. 2017, 34, 580–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlachos, P.A.; Theotokis, A.; Pramatari, K.; Vrechopoulos, A. Consumer-retailer Emotional Attachment: Some Antecedents and the Moderating Role of Attachment Anxiety. Eur. J. Mark. 2010, 44, 1478–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brocato, E.D.; Baker, J.; Voorhees, C.M. Creating Consumer Attachment to Retail Service Firms through Sense of Place. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 200–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Yeh, R.K.-J.; Yen, D.C.; Sandoya, M.G. Antecedents of Emotional Attachment of Social Media Users. Serv. Ind. J. 2016, 36, 438–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, A.M.; Haenlein, M. Users of the World, Unite! The Challenges and Opportunities of Social Media. Bus. Horiz. 2010, 53, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VanMeter, R.A.; Grisaffe, D.B.; Chonko, L.B. Of “Likes” and “Pins”: The Effects of Consumers’ Attachment to Social Media. J. Interact. Mark. 2015, 32, 70–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, M. Does Internet and Computer “Addiction” Exist? Some Case Study Evidence. CyberPsychol. Behav. 2000, 3, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandell, J.J. Internet Addiction on Campus: The Vulnerability of College Students. CyberPsychol. Behav. 1998, 1, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Hu, L.; Wang, G. Moderating Role of Addiction to Social Media Usage in Managing Cultural Intelligence and Cultural Identity Change. Inf. Technol. People 2020, 34, 704–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackwell, D.; Leaman, C.; Tramposch, R.; Osborne, C.; Liss, M. Extraversion, Neuroticism, Attachment Style and Fear of Missing out as Predictors of Social Media Use and Addiction. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2017, 116, 69–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Arienzo, M.C.; Boursier, V.; Griffiths, M.D. Addiction to Social Media and Attachment Styles: A Systematic Literature Review. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2019, 17, 1094–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altuwairiqi, M.; Jiang, N.; Ali, R. Problematic Attachment to Social Media: Five Behavioural Archetypes. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaposi, I. The Culture and Politics of Internet Use among Young People in Kuwait. Cyberpsychology 2014, 8, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainsworth, M.S.; Bowlby, J. An Ethological Approach to Personality Development. Am. Psychol. 1991, 46, 333–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainsworth, M.D.S.; Bell, S.M. Attachment, Exploration, and Separation: Illustrated by the Behavior of One-Year-Olds in a Strange Situation. Child Dev. 1970, 41, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowlby, J. Attachment and Loss: Vol. 1. Attachment; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, W.W.K.; Yuen, A.H.K. Understanding Online Knowledge Sharing: An Interpersonal Relationship Perspective. Comput. Educ. 2011, 56, 210–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.W.K.; Chan, A. Knowledge Sharing and Social Media: Altruism, Perceived Online Attachment Motivation, and Perceived Online Relationship Commitment. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 39, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, M.E.; Roberts, J.A. Phubbed and Alone: Phone Snubbing, Social Exclusion, and Attachment to Social Media. J. Assoc. Consum. Res. 2017, 2, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helme-Guizon, A.; Caldara, C.; Raies, K. “Bff”: Best Facebook Forever? The Impact of Social Media Attachment on the Attitude towards Brand Presence on Facebook. Mark. ZFP J. Res. Manag. 2013, 35, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VanMeter, R.; Syrdal, H.A.; Powell-Mantel, S.; Grisaffe, D.B.; Nesson, E.T. Don’t Just “Like” Me, Promote Me: How Attachment and Attitude Influence Brand Related Behaviors on Social Media. J. Interact. Mark. 2018, 43, 83–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algharabat, R.S. Linking Social Media Marketing Activities with Brand Love: The Mediating Role of Self-Expressive Brands. Kybernetes 2017, 46, 1801–1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moslehpour, M.; Dadvari, A.; Nugroho, W.; Do, B.-R. The Dynamic Stimulus of Social Media Marketing on Purchase Intention of Indonesian Airline Products and Services. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2020, 33, 561–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, C.J.; Sullivan, M.W. The Measurement and Determinants of Brand Equity: A Financial Approach. Mark. Sci. 1993, 12, 28–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaker, D.A. Managing Brand Equity: Capitalizing on the Value of a Brand Name; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Keller, K.L. Conceptualizing, Measuring, and Managing Customer-Based Brand Equity. J. Mark. 1993, 57, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Gon Kim, W.; An, J.A. The Effect of Consumer-based Brand Equity on Firms’ Financial Performance. J. Consum. Mark. 2003, 20, 335–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lassar, W.; Mittal, B.; Sharma, A. Measuring Customer-based Brand Equity. J. Consum. Mark. 1995, 12, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, L. Brands and Brand Equity: Definition and Management. Manag. Decis. 2000, 38, 662–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, V. Network Models for Estimating Brand-Specific Effects in Multi-Attribute Marketing Models. Manag. Sci. 1979, 25, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farquhar, P.H. Managing Brand Equity. Mark. Res. 1989, 1, 24–33. [Google Scholar]

- Washburn, J.H.; Plank, R.E. Measuring Brand Equity: An Evaluation of a Consumer-Based Brand Equity Scale. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2002, 10, 46–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atilgan, E.; Aksoy, Ş.; Akinci, S. Determinants of the Brand Equity: A Verification Approach in the Beverage Industry in Turkey. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2005, 23, 237–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schivinski, B.; Dabrowski, D. The Impact of Brand Communication on Brand Equity through Facebook. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2015, 9, 31–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morra, M.C.; Ceruti, F.; Chierici, R.; Di Gregorio, A. Social vs Traditional Media Communication: Brand Origin Associations Strike a Chord. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2017, 12, 2–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, B.; Donthu, N. Developing and Validating a Multidimensional Consumer-Based Brand Equity Scale. J. Bus. Res. 2001, 52, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaker, D.A. Building Strong Brands; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Kapfarer, J.-N. The New Strategic Brand Management: Creating and Sustaining Brand Equity Long Term; Kogan Page: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Aaker, D.A. Measuring Brand Equity across Products and Markets. Calif. Manag. Rev. 1996, 38, 102–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, U. The Impact of Source Credible Online Reviews on Purchase Intention: The Mediating Roles of Brand Equity Dimensions. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2019, 13, 142–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brochado, A.; Oliveira, F. Brand Equity in the Portuguese Vinho Verde “Green Wine” Market. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2018, 30, 2–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Oh, K.W. Which Consumer Associations Can Build a Sustainable Fashion Brand Image? Evidence from Fast Fashion Brands. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, K.L. Strategic Brand Management: Building, Measuring, and Managing Brand Equity, Global Edition; Pearson Education Limited: Harlow, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Tsordia, C.; Papadimitriou, D.; Parganas, P. The Influence of Sport Sponsorship on Brand Equity and Purchase Behavior. J. Strateg. Mark. 2018, 26, 85–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeithaml, V.A. Consumer Perceptions of Price, Quality, and Value: A Means-End Model and Synthesis of Evidence. J. Mark. 1988, 52, 2–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.T.; Wong, I.A.; Tseng, T.-H.; Chang, A.W.-Y.; Phau, I. Applying Consumer-Based Brand Equity in Luxury Hotel Branding. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 81, 192–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalilvand, M.R.; Samiei, N.; Mahdavinia, S.H. The Effect of Brand Equity Components on Purchase Intention: An Application of Aaker’s Model in the Automobile Industry. Int. Bus. Manag. 2011, 2, 149–158. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, P.C.S.; Yeh, G.Y.-Y.; Hsiao, C.-R. The Effect of Store Image and Service Quality on Brand Image and Purchase Intention for Private Label Brands. Australas. Mark. J. 2011, 19, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Summerlin, R.; Powell, W. Effect of Interactivity Level and Price on Online Purchase Intention. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2022, 17, 652–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinson, R.; Boateng, H.; Renner, A.; Kosiba, J.P.B. Antecedents and Consequences of Customer Engagement on Facebook: An Attachment Theory Perspective. JRIM 2019, 13, 204–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. Beyond Boredom and Anxiety; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Martins, J.; Costa, C.; Oliveira, T.; Gonçalves, R.; Branco, F. How Smartphone Advertising Influences Consumers’ Purchase Intention. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 94, 378–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, D.L.; Novak, T.P. Flow Online: Lessons Learned and Future Prospects. J. Interact. Mark. 2009, 23, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak, T.P.; Hoffman, D.L.; Yung, Y.-F. Measuring the Customer Experience in Online Environments: A Structural Modeling Approach. Mark. Sci. 2000, 19, 22–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, D.L.; Novak, T.P. Marketing in Hypermedia Computer-Mediated Environments: Conceptual Foundations. J. Mark. 1996, 60, 50–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuevas, L.; Lyu, J.; Lim, H. Flow Matters: Antecedents and Outcomes of Flow Experience in Social Search on Instagram. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2021, 15, 49–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koufaris, M. Applying the Technology Acceptance Model and Flow Theory to Online Consumer Behavior. Inf. Syst. Res. 2002, 13, 205–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luna, D.; Peracchio, L.A.; De Juan, M.D. Cross-Cultural and Cognitive Aspects of Web Site Navigation. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2002, 30, 397–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korzaan, M.L. Going with the Flow: Predicting Online Purchase Intentions. J. Comput. Inf. Syst. 2003, 43, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hausman, A.V.; Siekpe, J.S. The Effect of Web Interface Features on Consumer Online Purchase Intentions. J. Bus. Res. 2009, 62, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, E. Online Experiences and Virtual Goods Purchase Intention. Internet Res. 2012, 22, 252–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarei, A.; Farjoo, H.; Bagheri Garabollagh, H. How Social Media Marketing Activities (SMMAs) and Brand Equity Affect the Customer’s Response: Does Overall Flow Moderate It? J. Internet Commer. 2022, 21, 160–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zhang, W.; Daim, T.U. Investigating Consumer Purchase Intention in Online Social Media Marketing: A Case Study of Tiktok. Technol. Soc. 2023, 74, 102289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.N.; Sivakumar, K. Flow and Internet Shopping Behavior: A Conceptual Model and Research Propositions. J. Bus. Res. 2004, 57, 1199–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toor, A.; Husnain, M.; Hussain, T. The Impact of Social Network Marketing on Consumer Purchase Intention in Pakistan: Consumer Engagement as a Mediator. Asian J. Bus. Account. 2017, 10, 167–199. [Google Scholar]

- Bushara, M.A.; Abdou, A.H.; Hassan, T.H.; Sobaih, A.E.E.; Albohnayh, A.S.M.; Alshammari, W.G.; Aldoreeb, M.; Elsaed, A.A.; Elsaied, M.A. Power of Social Media Marketing: How Perceived Value Mediates the Impact on Restaurant Followers’ Purchase Intention, Willingness to Pay a Premium Price, and E-WoM? Sustainability 2023, 15, 5331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anas, A.M.; Abdou, A.H.; Hassan, T.H.; Alrefae, W.M.M.; Daradkeh, F.M.; El-Amin, M.A.-M.M.; Kegour, A.B.A.; Alboray, H.M.M. Satisfaction on the Driving Seat: Exploring the Influence of Social Media Marketing Activities on Followers’ Purchase Intention in the Restaurant Industry Context. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdanparast, A.; Joseph, M.; Muniz, F. Consumer Based Brand Equity in the 21st Century: An Examination of the Role of Social Media Marketing. Young Consum. 2016, 17, 243–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eysenck, M.W.; Keane, M.T. Cognitive Psychology: A Student’s Handbook; Psychology Press-Taylor & Francis e-Library: Hove, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Spackman, J.S.; Larsen, R. Evaluating the Impact of Social Media Marketing on Online Course Registration. J. Contin. High. Educ. 2017, 65, 151–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tybout, A.M.; Calder, B.J.; Sternthal, B. Using Information Processing Theory to Design Marketing Strategies. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, G.A. The Magical Number Seven, plus or Minus Two: Some Limits on Our Capacity for Processing Information. Psychol. Rev. 1956, 63, 81–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leong, S.M. Consumer Decision Making for Common, Repeat-Purchase Products: A Dual Replication. J. Consum. Psychol. 1993, 2, 193–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M.; Park, B. Sustainable Corporate Social Media Marketing Based on Message Structural Features: Firm Size Plays a Significant Role as a Moderator. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobb-Walgren, C.J.; Ruble, C.A.; Donthu, N. Brand Equity, Brand Preference, and Purchase Intent. J. Advert. 1995, 24, 25–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, A.S. Antecedents of Consumers’ Engagement with Brand-Related Content on Social Media. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2019, 37, 386–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coursaris, C.K.; Osch, W.V.; Balogh, B.A. Do Facebook Likes Lead to Shares or Sales? Exploring the Empirical Links between Social Media Content, Brand Equity, Purchase Intention, and Engagement. In Proceedings of the 2016 49th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Koloa, HI, USA, 5–8 January 2016; IEEE Computer Society: Washington, DC, USA, 2016; pp. 3546–3555. [Google Scholar]

- Schlosser, A.E. Posting versus Lurking: Communicating in a Multiple Audience Context. J. Consum. Res. 2005, 32, 260–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marett, K.; Joshi, K.D. The Decision to Share Information and Rumors: Examining the Role of Motivation in an Online Discussion Forum. Commun. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2009, 24, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, S.; Lai, H.; Chou, Y. Knowledge-sharing Intention in Professional Virtual Communities: A Comparison between Posters and Lurkers. J. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2015, 66, 2494–2510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Li, G.; Huang, S.S. Perceived Online Community Support, Member Relations, and Commitment: Differences between Posters and Lurkers. Inf. Manag. 2017, 54, 154–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nonnecke, B.; Preece, J. Why Lurkers Lurk. In Seventh Americas Conference on Information Systems 2001 Proceedings, AISEL; AIS Electronic Library (AISeL): Atlanta, GA, USA, 2001; pp. 1521–1530. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, N.; Rau, P.P.-L.; Ma, L. Understanding Lurkers in Online Communities: A Literature Review. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 38, 110–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurtubise, K.; Pratte, G.; Rivard, L.; Berbari, J.; Héguy, L.; Camden, C. Exploring Engagement in a Virtual Community of Practice in Pediatric Rehabilitation: Who Are Non-Users, Lurkers, and Posters? Disabil. Rehabil. 2019, 41, 983–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beukeboom, C.J.; Kerkhof, P.; De Vries, M. Does a Virtual Like Cause Actual Liking? How Following a Brand’s Facebook Updates Enhances Brand Evaluations and Purchase Intention. J. Interact. Mark. 2015, 32, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambo, S.; Özad, B. The Influence of Uncertainty Reduction Strategy over Social Network Sites Preference. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2021, 16, 116–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede-Insights. Country Comparison Tool. Available online: https://www.hofstede-insights.com/country-comparison-tool?countries=india%2Cmalaysia%2Cturkey%2Cunited+states (accessed on 30 July 2024).

- Statista. Social Media Advertising—Turkey. Available online: https://www.statista.com/outlook/dmo/digital-advertising/social-media-advertising/turkey (accessed on 30 July 2024).

- Bruhn, M.; Schoenmueller, V.; Schäfer, D.B. Are Social Media Replacing Traditional Media in Terms of Brand Equity Creation? Manag. Res. Rev. 2012, 35, 770–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-F.; Chang, Y.-Y. Airline Brand Equity, Brand Preference, and Purchase Intentions—The Moderating Effects of Switching Costs. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2008, 14, 40–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabachnick, B.G.; Fidell, L.S. Using Multivariate Statistics; Pearson Education, Inc.: Boston, MA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.J.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis; Pearson: Essex, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally, J.C. Psychometric Theory; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Baboo, S.; Nunkoo, R.; Kock, F. Social Media Attachment: Conceptualization and Formative Index Construction. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 139, 437–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lleo, A.; Ruiz-Palomino, P.; Viles, E.; Muñoz-Villamizar, A.F. A Valid and Reliable Scale for Measuring Middle Managers’ Trustworthiness in Continuous Improvement. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2021, 242, 108280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, S.; Gunasekar, S.; Dixit, S.K.; Das, P. Gastro-Nostalgia: Towards a Higher Order Measurement Scale Based on Two Gastro Festivals. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2022, 47, 293–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle, J.L. IBM SPSS Amos 21 User’s Guide; IBM Corporation: Armonk, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Gudergan, S.P. Advanced Issues in Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Aiken, L.S.; West, S.G. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Abubakar, A.M.; Megeirhi, H.A.; Shneikat, B. Tolerance for Workplace Incivility, Employee Cynicism and Job Search Behavior. Serv. Ind. J. 2018, 38, 629–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Wang, H.; Wang, Z.; Koondhar, M.A.; Ji, L.; Kong, R. The Nexus between Formal Credit and E-Commerce Utilization of Entrepreneurial Farmers in Rural China: A Mediation Analysis. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2021, 16, 900–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The Moderator–Mediator Variable Distinction in Social Psychological Research: Conceptual, Strategic, and Statistical Considerations. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacKinnon, D.P. Introduction to Statistical Mediation Analysis; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates—Taylor & Francis Group: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical Mediation Analysis in the New Millennium. Commun. Monogr. 2009, 76, 408–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Lynch, J.G., Jr.; Chen, Q. Reconsidering Baron and Kenny: Myths and Truths about Mediation Analysis. J. Consum. Res. 2010, 37, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Interbrand. Best Global Brands 2023. Available online: https://interbrand.com/best-global-brands/ (accessed on 15 May 2024).

- Ahmed, R.U. Social Media Marketing, Shoppers’ Store Love and Loyalty. MIP 2022, 40, 153–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Du, M. Utilization and Effectiveness of Social Media Message Strategy: How B2B Brands Differ from B2C Brands. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2020, 35, 721–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pongpaew, W.; Speece, M.; Tiangsoongnern, L. Social Presence and Customer Brand Engagement on Facebook Brand Pages. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2017, 26, 262–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Construct | Dimension(s) | Item | Mean | Std. Deviation | Variance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attachment to social media | Influence, advice, and affirmed | INFL1 | 3.78 | 2.00 | 4.02 |

| INFL2 | 3.55 | 2.08 | 4.32 | ||

| INFL3 | 3.75 | 2.04 | 4.18 | ||

| INFL4 | 4.05 | 1.99 | 3.94 | ||

| INFL5 | 4.17 | 1.96 | 3.84 | ||

| ADV2 | 4.17 | 1.92 | 3.69 | ||

| ADV3 | 4.22 | 1.89 | 3.57 | ||

| AFF2 | 4.08 | 1.98 | 3.90 | ||

| Connecting | CON1 | 5.71 | 1.49 | 2.22 | |

| CON2 | 6.01 | 1.26 | 1.59 | ||

| CON3 | 5.72 | 1.38 | 1.90 | ||

| CON4 | 5.74 | 1.39 | 1.92 | ||

| Informed | INF1 | 5.52 | 1.46 | 2.14 | |

| INF2 | 5.77 | 1.33 | 1.76 | ||

| INF3 | 5.52 | 1.53 | 2.33 | ||

| Enjoyment | ENJ1 | 5.24 | 1.56 | 2.42 | |

| ENJ2 | 5.32 | 1.54 | 2.36 | ||

| ENJ3 | 5.36 | 1.45 | 2.11 | ||

| Nostalgia | NOS1 | 5.62 | 1.44 | 2.08 | |

| NOS2 | 5.28 | 1.60 | 2.57 | ||

| NOS3 | 5.44 | 1.54 | 2.37 | ||

| Perceived social media marketing activities | Trendiness, interaction, and entertainment | TRE1 | 5.34 | 1.39 | 1.94 |

| TRE2 | 5.69 | 1.40 | 1.97 | ||

| INT1 | 4.98 | 1.55 | 2.41 | ||

| INT2 | 5.09 | 1.56 | 2.42 | ||

| INT3 | 5.17 | 1.54 | 2.38 | ||

| ENT2 | 4.93 | 1.51 | 2.28 | ||

| Word of mouth | WOM1 | 4.60 | 1.72 | 2.98 | |

| WOM2 | 4.03 | 1.93 | 3.74 | ||

| Brand equity | Brand awareness and associations | BAW1 | 6.17 | 1.22 | 1.49 |

| BAW2 | 6.28 | 1.14 | 1.30 | ||

| BAW3 | 6.30 | 1.14 | 1.30 | ||

| BAS1 | 6.09 | 1.24 | 1.53 | ||

| BAS2 | 6.37 | 1.18 | 1.38 | ||

| BAS3 | 6.31 | 1.14 | 1.29 | ||

| Brand loyalty | BLO1 | 4.69 | 1.89 | 3.59 | |

| BLO2 | 5.25 | 1.80 | 3.26 | ||

| BLO3 | 4.69 | 1.98 | 3.90 | ||

| Perceived quality | PQ1 | 5.65 | 1.47 | 2.16 | |

| PQ2 | 5.49 | 1.54 | 2.37 | ||

| PQ3 | 5.70 | 1.35 | 1.82 | ||

| Purchase intentions | (Single factor) | PI1 | 5.48 | 1.62 | 2.63 |

| PI2 | 5.41 | 1.66 | 2.75 | ||

| PI3 | 5.38 | 1.69 | 2.87 |

| Construct | Dimension(s) | Item | Factor Loadings | Cronbach’s Alpha | TVE | KMO |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attachment to social media | Influence, advice, and affirmed | INFL1 | 0.84 | 0.93 | 75.8% | 0.931 |

| INFL2 | 0.89 | |||||

| INFL3 | 0.87 | |||||

| INFL4 | 0.82 | |||||

| INFL5 | 0.79 | |||||

| ADV2 | 0.61 | |||||

| ADV3 | 0.65 | |||||

| AFF2 | 0.72 | |||||

| Connecting | CON1 | 0.83 | ||||

| CON2 | 0.81 | |||||

| CON3 | 0.83 | |||||

| CON4 | 0.79 | |||||

| Informed | INF1 | 0.78 | ||||

| INF2 | 0.81 | |||||

| INF3 | 0.82 | |||||

| Enjoyment | ENJ1 | 0.81 | ||||

| ENJ2 | 0.81 | |||||

| ENJ3 | 0.70 | |||||

| Nostalgia | NOS1 | 0.69 | ||||

| NOS2 | 0.84 | |||||

| NOS3 | 0.80 | |||||

| Perceived social media marketing activities | Trendiness, interaction, and entertainment | TRE1 | 0.81 | 0.87 | 65.8% | 0.860 |

| TRE2 | 0.82 | |||||

| INT1 | 0.64 | |||||

| INT2 | 0.67 | |||||

| INT3 | 0.73 | |||||

| ENT2 | 0.61 | |||||

| Word of mouth | WOM1 | 0.78 | ||||

| WOM2 | 0.87 | |||||

| Brand equity | Brand awareness and associations | BAW1 | 0.81 | 0.91 | 78.8% | 0.906 |

| BAW2 | 0.88 | |||||

| BAW3 | 0.88 | |||||

| BAS1 | 0.76 | |||||

| BAS2 | 0.82 | |||||

| BAS3 | 0.82 | |||||

| Brand loyalty | BLO1 | 0.89 | ||||

| BLO2 | 0.76 | |||||

| BLO3 | 0.83 | |||||

| Perceived quality | PQ1 | 0.80 | ||||

| PQ2 | 0.83 | |||||

| PQ3 | 0.77 | |||||

| Purchase intentions | (Single factor) | PI1 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 90.6% | 0.769 |

| PI2 | 0.96 | |||||

| PI3 | 0.95 |

| Construct | Dimension(s) | Item | Factor Loadings | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attachment to social media | Influence, advice, and affirmed | INFL1 | 0.85 | 0.86 | 0.56 |

| INFL2 | 0.84 | ||||

| INFL3 | 0.85 | ||||

| INFL4 | 0.85 | ||||

| INFL5 | 0.82 | ||||

| ADV2 | 0.58 | ||||

| ADV3 | 0.64 | ||||

| AFF2 | 0.70 | ||||

| Connecting | CON1 | 0.78 | |||

| CON2 | 0.83 | ||||

| CON3 | 0.90 | ||||

| CON4 | 0.88 | ||||

| Informed | INF1 | 0.80 | |||

| INF2 | 0.91 | ||||

| INF3 | 0.84 | ||||

| Enjoyment | ENJ1 | 0.85 | |||

| ENJ2 | 0.85 | ||||

| ENJ3 | 0.81 | ||||

| Nostalgia | NOS1 | 0.81 | |||

| NOS2 | 0.90 | ||||

| NOS3 | 0.90 | ||||

| Perceived social media marketing activities | Trendiness, interaction, and entertainment | TRE1 | 0.69 | 0.84 | 0.72 |

| TRE2 | 0.69 | ||||

| INT1 | 0.69 | ||||

| INT2 | 0.63 | ||||

| INT3 | 0.70 | ||||

| ENT2 | 0.75 | ||||

| Word of mouth | WOM1 | 0.84 | |||

| WOM2 | 0.66 | ||||

| Brand equity | Brand awareness and associations | BAW1 | 0.83 | 0.82 | 0.62 |

| BAW2 | 0.91 | ||||

| BAW3 | 0.90 | ||||

| BAS1 | 0.74 | ||||

| BAS2 | 0.75 | ||||

| BAS3 | 0.76 | ||||

| Brand loyalty | BLO1 | 0.77 | |||

| BLO2 | 0.91 | ||||

| BLO3 | 0.87 | ||||

| Perceived quality | PQ1 | 0.94 | |||

| PQ2 | 0.91 | ||||

| PQ3 | 0.78 | ||||

| Purchase intentions | (Single factor) | PI1 | 0.93 | 0.95 | 0.86 |

| PI2 | 0.94 | ||||

| PI3 | 0.91 |

| Mean | Std. Deviation | ASM | Perceived SMMAs | BE | PIs | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASM | 4.96 | 1.10 | 1 | |||

| Perceived SMMAs | 4.98 | 1.14 | 0.59 ** | 1 | ||

| BE | 5.75 | 1.04 | 0.51 ** | 0.64 ** | 1 | |

| PIs | 5.42 | 1.58 | 0.53 ** | 0.70 ** | 0.80 ** | 1 |

| Index | Result |

|---|---|

| Chi/df (CMIN/df) | 2.73 |

| GFI | 0.88 |

| AGFI | 0.87 |

| CFI | 0.95 |

| RMSEA | 0.044 |

| Hypothesis | Direct Effect (β) | Direct Effect (t-Value) | Indirect Effect (β) | Indirect Effect (t-Value) | Lower Bound | Upper Bound | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H5. Perceived SMMAs→BE→PIs | 0.31 *** | 13.21 | 0.37 *** | 16.48 | 0.34 | 0.41 | Supported (Partial mediation) |

| Hypothesis | β | t-Value | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| H1. ASM→Perceived SMMAs | 0.59 *** | 22.09 | Supported |

| H2. Perceived SMMAs→PIs | 0.31 *** | 13.21 | Supported |

| H3. Perceived SMMAs→BE | 0.63 *** | 24.36 | Supported |

| H4. BE→PIs | 0.60 *** | 25.05 | Supported |

| H5. Perceived SMMAs→ BE→PIs | 0.37 *** | 16.48 | Supported |

| H6. SMMAxSMUF (-) moderation on perceived SMMAs→BE | −0.06 ** | −2.45 | Supported |

| H7. SMMAxSMUF (-) moderation on perceived SMMAs→PIs | −0.04 * | −1.94 | Supported |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Karayalçın, C.; Yaraş, E. Consumers’ Psychology Regarding Attachment to Social Media and Usage Frequency: A Mediated-Moderated Model. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 676. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14080676

Karayalçın C, Yaraş E. Consumers’ Psychology Regarding Attachment to Social Media and Usage Frequency: A Mediated-Moderated Model. Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 14(8):676. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14080676

Chicago/Turabian StyleKarayalçın, Cem, and Eyyup Yaraş. 2024. "Consumers’ Psychology Regarding Attachment to Social Media and Usage Frequency: A Mediated-Moderated Model" Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 8: 676. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14080676

APA StyleKarayalçın, C., & Yaraş, E. (2024). Consumers’ Psychology Regarding Attachment to Social Media and Usage Frequency: A Mediated-Moderated Model. Behavioral Sciences, 14(8), 676. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14080676