Gender Differences in the Longitudinal Linkages between Fear of COVID-19 and Internet Game Addiction: A Moderated Multiple Mediation Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Fear of COVID-19 and IGA

1.2. Mediating Role of Loneliness

1.3. Mediating Role of Depression

1.4. Multiple Mediating Effects of Loneliness and Depression

1.5. Gender Differences

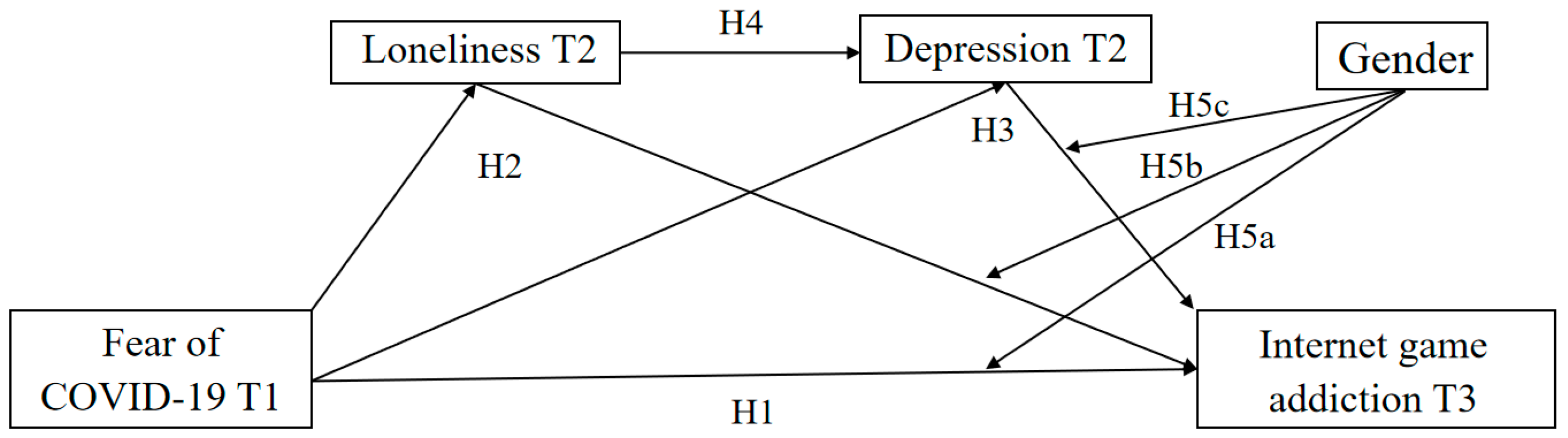

1.6. The Present Study

2. Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Measurements

2.2.1. Fear of COVID-19

2.2.2. Loneliness

2.2.3. The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9)

2.2.4. Internet Game Addiction

2.3. Data Analysis

2.4. Testing the Common Method Bias (CMB)

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary Analyses

3.2. Testing the Measurement Model

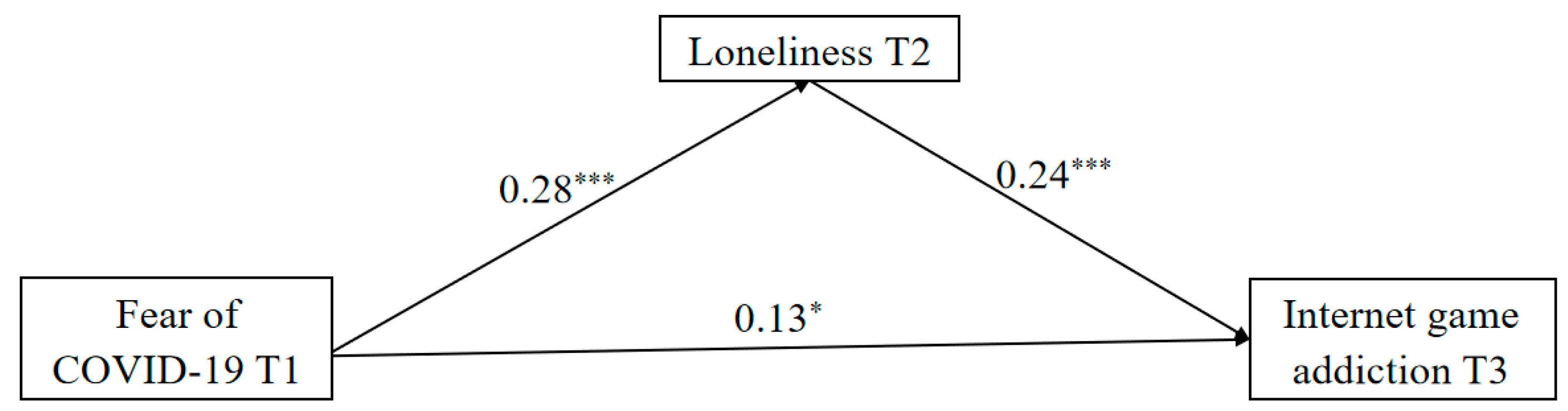

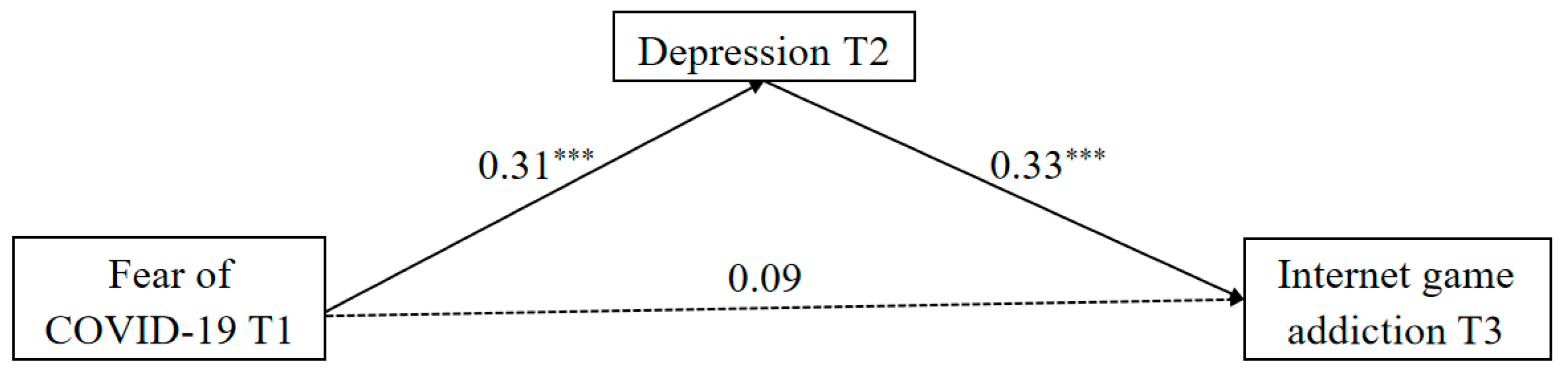

3.3. Testing the Mediation Model

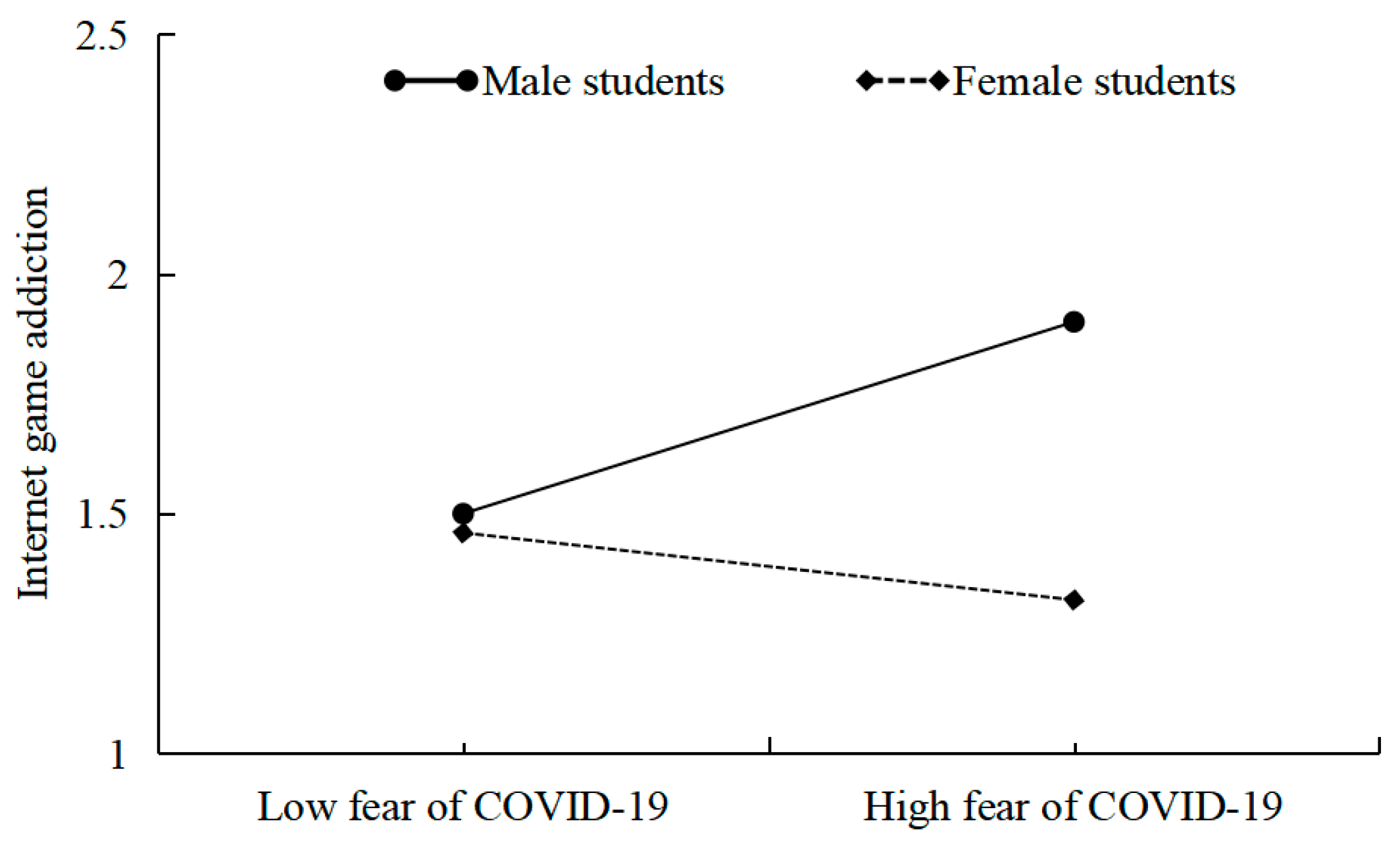

3.4. Testing the Moderated Multiple Mediation Model

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications

4.2. Limitations and Future Research Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Haikalis, M.; Doucette, H.; Meisel, M.K.; Birch, K.; Barnett, N.P. Changes in college student anxiety and depression from pre- to during-COVID-19: Perceived stress, academic challenges, loneliness, and positive perceptions. Emerg. Adulthood 2022, 10, 534–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Havewala, M.; Zhu, Q. COVID-19 stressful life events and mental health: Personality and coping styles as moderators. J. Am. Coll. Health 2022, 72, 1068–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Techreport. Online Gaming Statistics: Trends & Analysis of the Industry. 2023. Available online: https://techreport.com/statistics/gaming-statistics/ (accessed on 26 June 2023).

- Kuss, D.J.; Kristensen, A.M.; Lopez-Fernandez, O. Internet addictions outside of Europe: A systematic literature review. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2021, 115, 106621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gioia, F.; Colella, G.M.; Boursier, V. Evidence on problematic online gaming and social anxiety over the past ten years: A systematic literature review. Curr. Addict. Rep. 2022, 9, 32–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosendo-Rios, V.; Trott, S.; Shukla, P. Systematic literature review online gaming addiction among children and young adults: A framework and research agenda. Addict. Behav. 2022, 129, 107238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arya, S.; Sharma, M.K.; Rathee, S.; Singh, P. COVID-19 pandemic, social isolation, and online gaming addiction: Evidence from two case reports. J. Indian Assoc. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2022, 18, 196–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putra, P.Y.; Fithriyah, I.; Zahra, Z. Internet addiction and online gaming disorder in children and adolescents during COVID-19 pandemic: A Systematic Review. Psychiatry Investig. 2023, 20, 196–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alimoradi, Z.; Lotfi, A.; Lin, C.Y.; Griffiths, M.D.; Pakpour, A.H. Estimation of behavioral addiction prevalence during COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Curr. Addict. Rep. 2022, 9, 486–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Servidio, R.; Bartolo, M.G.; Palermiti, A.L.; Costabile, A. Fear of COVID-19, depression, anxiety, and their association with Internet addiction disorder in a sample of Italian students. J. Affect. Disord. Rep. 2021, 4, 100097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moniri, R.; Pahlevani, N.K.; Lavasani, F.F. Investigating anxiety and fear of COVID-19 as predictors of internet addiction with the mediating role of self-compassion and cognitive emotion regulation. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 841870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayis, A.R.; Satici, B.; Deniz, M.E.; Satici, S.A.; Griffiths, M.D. Fear of COVID-19, loneliness, smartphone addiction, and mental wellbeing among the Turkish general population: A serial mediation model. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2022, 41, 2484–2496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yam, F.C.; Korkmaz, O.; Griffiths, M.D. The association between fear of COVID-19 and smartphone addiction among individuals: The mediating and moderating role of cyberchondria severity. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 42, 2377–2390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.L.; Sheng, J.R.; Wang, H.Z. The association between mobile game addiction and depression, social anxiety, and loneliness. Front. Public Health 2019, 7, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kardefelt-Winther, D. A conceptual and methodological critique of internet addiction research: Towards a model of compensatory internet use. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 31, 351–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boursier, V.; Gioia, F.; Musetti, A.; Schimmenti, A. COVID-19-related fears, stress and depression in adolescents: The role of loneliness and relational closeness to online friends. J. Hum. Behav. Soc. Environ. 2023, 33, 296–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boysan, M.; Eşkisu, M.; Çam, Z. Relationships between fear of COVID-19, cyberchondria, intolerance of uncertainty, and obsessional probabilistic inferences: A structural equation model. Scand. J. Psychol. 2022, 63, 439–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montag, C.; Sindermann, C.; Rozgonjuk, D.; Yang, S.; Elhai, J.D.; Yang, H. Investigating links between fear of COVID-19, neuroticism, social networks use disorder, and smartphone use disorder tendencies. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 682837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, Y. Physical activity and mental health in sports university students during the COVID-19 school confinement in Shanghai. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 977072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peker, A.; Cengiz, S.; Yildiz, M.N. The mediation relationship between life satisfaction and subjective vitality fear of COVID-19 and problematic internet use. Klinik Psikiyatri Dergisi-Turk. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2021, 24, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, M.H.; Eres, R.; Vasan, S. Understanding loneliness in the twenty-first century: An update on correlates, risk factors, and potential solutions. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2020, 55, 793–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eberle, J.; Hobrecht, J. The lonely struggle with autonomy: A case study of first-year university students’ experiences during emergency online teaching. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2021, 121, 106804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, A.M.; Tibubos, A.N.; Mülder, L.M.; Reichel, J.L.; Schäfer, M.; Heller, S.; Pfirrmann, D.; Edelmann, D.; Dietz, P.; Rigotti, T.; et al. The impact of lockdown stress and loneliness during the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health among university students in Germany. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 22637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, H.B. Psychosocial stress from the perspective of self theory. In Psychosocial Stress: Perspectives on Structure, Theory, Life Course and Methods; Kaplan, H.B., Ed.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.Y.; Ko, D.W.; Lee, H. Loneliness, regulatory focus, inter-personal competence, and online game addiction: A moderated mediation model. Internet Res. 2019, 29, 381–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mun, I.B.; Lee, S. A longitudinal study of the impact of parental loneliness on adolescents’ online game addiction: The mediating roles of adolescents’ social skill deficits and loneliness. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2022, 136, 107375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batmaz, H.; Celik, E. Examining the online game addiction level in terms of sensation seeking and loneliness in university Students. Addicta Turk. J. Addict. 2021, 8, 126–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thapar, A.; Eyre, O.; Patel, V.; Brent, D. Depression in young people. Lancet 2022, 400, 617–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.M.; Zhang, Y.L.; Yu, G.L. Prevalence of mental health problems among college students in Chinese mainland from 2010 to 2020: A meta-analysis. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2022, 30, 991–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çıkrıkçı, Ö.; Çıkrıkçı, N.; Griffiths, M. Fear of COVID-19, stress and depression: A meta-analytic test of the mediating role of anxiety. Psychol. Psychother. Theory Res. Pract. 2022, 95, 853–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bağatarhan, T.; Siyez, D.M. Rumination and internet addiction among adolescents: The mediating role of depression. Child Adolesc. Soc. Work J. 2022, 39, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Zhang, Z.H.; Bi, L.; Wu, X.S.; Wang, W.J.; Li, Y.F.; Sun, Y.H. The association between life events and internet addiction among Chinese vocational school students: The mediating role of depression. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 70, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Li, X.; Gong, X. Parental phubbing and internet gaming addiction in children: Mediating roles of parent–child relationships and depressive symptoms. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2022, 25, 512–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmud, M.S.; Talukder, M.U.; Rahman, S.M. Does ‘Fear of COVID-19’ trigger future career anxiety? An empirical investigation considering depression from COVID-19 as a mediator. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2021, 67, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erbiçer, E.S.; Metin, A.; Çetinkaya, A.; Şen, S. The relationship between fear of COVID-19 and depression, anxiety, and stress. Eur. Psychol. 2022, 26, 323–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyun, G.J.; Han, D.H.; Lee, Y.S.; Kang, K.D.; Yoo, S.K.; Chung, U.S.; Renshaw, P.F. Risk factors associated with online game addiction: A hierarchical model. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 48, 706–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Zhang, G.; Yang, X.; Zhang, H.; Lei, L.; Wang, P. Online gaming addiction and depressive symptoms among game players of the glory of the king in China: The mediating role of affect balance and the moderating role of flow experience. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2022, 20, 3191–3204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mun, I.B.; Lee, S. The influence of parents’ depression on children’s online gaming addiction: Testing the mediating effects of intrusive parenting and social motivation on children’s online gaming behavior. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 42, 4991–5000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monroe, S.M.; Simons, A.D. Diathesis-stress theories in the context of life stress research: Implications for the depressive disorders. Psychol. Bull. 1991, 110, 406–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, M.; Tian, F.; Cui, Q.; Wu, H. Prevalence and its associated factors of depressive symptoms among Chinese college students during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Psychiatry. 2021, 21, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.M.; Cadigan, J.M.; Rhew, I.C. Increases in loneliness among young adults during the COVID-19 pandemic and association with increases in mental health problems. J. Adolesc. Health 2020, 67, 714–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaya, E.S.; Hillmann, T.E.; Reininger, K.M.; Gollwitzer, A.; Lincoln, T.M. Loneliness and psychotic symptoms: The mediating role of depression. Cognit. Ther. Res. 2017, 41, 106–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, L.; Han, X.; Li, D.; Hu, F.; Mo, B.; Liu, J. The association between loneliness and depression among Chinese college students: Affinity for aloneness and gender as moderators. Eur. J. Dev. Psychol. 2021, 18, 382–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metin, A.; Erbiçer, E.S.; Şen, S.; Çetinkaya, A. Gender and COVID-19 related fear and anxiety: A meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2022, 310, 384–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broche-Pérez, Y.; Fernández-Fleites, Z.; Jiménez-Puig, E.; Fernández-Castillo, E.; Rodríguez-Martin, B.C. Gender and fear of COVID-19 in a Cuban population sample. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2022, 20, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wickens, C.M.; McDonald, A.J.; Elton-Marshall, T.; Wells, S.; Nigatu, Y.T.; Jankowicz, D.; Hamilton, H.A. Loneliness in the COVID-19 pandemic: Associations with age, gender and their interaction. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2021, 136, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, E.J.; Kim, H.S. Gender differences in smartphone addiction behaviors associated with parent–child bonding, parent–child communication, and parental mediation among Korean elementary school students. J. Addict. Nurs. 2018, 29, 244–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, H.; Li, X.; Zhou, J.; Nie, Q.; Zhou, J. The relationship between bullying victimization and online game addiction among Chinese early adolescents: The potential role of meaning in life and gender differences. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 116, 105261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debowska, A.; Horeczy, B.; Boduszek, D.; Dolinski, D. A repeated cross-sectional survey assessing university students’ stress, depression, anxiety, and suicidality in the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic in Poland. Psychol. Med. 2022, 52, 3744–3747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Wang, S. The role of cognitive distortion in online game addiction among Chinese adolescents. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2013, 35, 1468–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lütfi, S.E.; Ertan, E.S.; Balarba, E.; Maslak, A. COVID-19 and human flourishing: The moderating role of gender. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2021, 183, 111111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lathabhavan, R. Covid-19 effects on psychological outcomes: How do gender responses differ? Psychol. Rep. 2023, 126, 117–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayandele, O.; Ramos-Vera, C.A.; Iorfa, S.K.; Chovwen, C.O.; Olapegba, P.O. Exploring the complex pathways between the fear of covid-19 and preventive health behavior among Nigerians: Mediation and moderation analyses. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2021, 105, 701–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chappetta, K.C.; Barth, J.M. Gaming roles versus gender roles in online gameplay. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2022, 25, 162–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahorsu, D.K.; Lin, C.Y.; Imani, V.; Saffari, M.; Griffiths, M.D.; Pakpour, A.H. The fear of COVID-19 scale: Development and initial validation. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2022, 20, 1537–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chi, X.; Chen, S.; Chen, Y.; Chen, D.; Yu, Q.; Guo, T.; Cao, Q.; Zheng, X.; Huang, S.; Hossain, M.M.; et al. Psychometric evaluation of the fear of COVID-19 scale among Chinese population. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2022, 20, 1273–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, C.H.; Yao, G. Psychometric analysis of the short-form UCLA Loneliness Scale (ULS-8) in Taiwanese undergraduate students. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2008, 44, 1762–1771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hays, R.D.; DiMatteo, M.R. A short-form measure of loneliness. J. Personal. Assess. 1987, 51, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L. The PHQ-9: A new depression diagnostic and severity measure. Psychiatr. Ann. 2002, 32, 509–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.L.; Liang, W.; Chen, Z.M.; Zhang, H.M.; Zhang, J.H.; Weng, X.Q.; Yang, S.C.; Zhang, L.; Shen, L.J.; Zhang, Y.L. Validity and reliability of Patient Health Questionnaire-9 and Patient Health Questionnaire-2 to screen for depression among college students in China. Asia-Pac. Psychiatry 2013, 5, 268–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Z.; Yang, W. The development of different types of Internet addiction scale for undergraduates. Chin. Ment. Health J. 2006, 11, 754–757. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F.; Montoya, A.K.; Rockwood, N.J. The Analysis of Mechanisms and Their Contingencies: PROCESS versus Structural Equation Modeling. Australas. Mark. J. 2017, 25, 76–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, R.J. A test of missing completely at random for multivariate data with missing values. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1988, 83, 1198–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, S.; Tang, W.; Zhang, M.; Cao, W. Techniques for missing data in longitudinal studies and its application. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2014, 22, 1985–1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; Mackenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shir-Wise, M. Melting time and confined leisure under COVID-19 lockdown. World Leisure J. 2022, 64, 221–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vella, K.; Klarkowski, M.; Turkay, S.; Johnson, D. Making friends in online games: Gender differences and designing for greater social connectedness. Behav. Inform. Technol. 2020, 39, 917–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhai, J.D.; McKay, D.; Yang, H.; Minaya, C.; Montag, C.; Asmundson, G.J. Health anxiety related to problematic smartphone use and gaming disorder severity during COVID-19: Fear of missing out as a mediator. Hum. Behav. Emerg. Technol. 2021, 3, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melodia, F.; Canale, N.; Griffiths, M.D. The role of avoidance coping and escape motives in problematic online gaming: A systematic literature review. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2022, 20, 996–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartolic, S.K.; Boud, D.; Agapito, J.; Verpoorten, D.; Williams, S.; Lutze-Mann, L.; Matzat, U.; Moreno, M.M.; Polly, P.; Tai, J.; et al. A multi-institutional assessment of changes in higher education teaching and learning in the face of COVID-19. Educ Rev. 2022, 74, 517–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Maskari, A.; Al-Riyami, T.; Kunjumuhammed, S.K. Students academic and social concerns during COVID-19 pandemic. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2022, 27, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Yang, J.; Yue, L.; Xu, J.; Liu, X.; Li, W.; Cheng, H.; He, G. Impact of perception reduction of employment opportunities on employment pressure of college students under COVID-19 epidemic–joint moderating effects of employment policy support and job-searching self-efficacy. Front Psychol. 2022, 13, 986070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erzen, E.; Çikrikci, Ö. The effect of loneliness on depression: A meta-analysis. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2018, 64, 427–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tronnier, C.D. Harnessing attachment in addiction treatment: Regulation theory and the self-medication hypothesis. J. Soc. Work Pract. Addict. 2015, 15, 233–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winn, J.; Heeter, C. Gaming, gender, and time: Who makes time to play? Sex Roles 2009, 61, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, J.A. “I Ain’t No Girl”: Exploring gender stereotypes in the video game community. West. J. Commun. 2023, 87, 857–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, S.X.; Ewoldsen, D.R.; Ellithorpe, M.E.; Van Der Heide, B.; Rhodes, N. Gamer girl vs. girl gamer: Stereotypical gamer traits increase men’s play intention. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2022, 131, 107217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuss, D.J.; Kristensen, A.M.; Williams, A.J.; Lopez-Fernandez, O. To be or not to be a female gamer: A qualitative exploration of female gamer identity. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eagly, A.H. Sex differences in social behavior: Comparing social role theory and evolutionary psychology. Am. Psychol. 1997, 52, 1380–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, H.; Lin, W.; Chen, P. Counselling services and mental health for international Chinese college students in post-pandemic thailand. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lizarte Simón, E.J.; Khaled Gijón, M.; Galván Malagón, M.C.; Gijón Puerta, J. Challenge-obstacle stressors and cyberloafing among higher vocational education students: The moderating role of smartphone addiction and Maladaptive. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1358634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Gender | Time 1 (M ± SD) | t Value | Time 3 (M ± SD) | t Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hours/day of game play | Males | 2.45 ± 1.75 | 6.33 *** | 3.03 ± 2.12 | 3.51 ** |

| Females | 1.33 ± 1.43 | 2.21 ± 1.64 | |||

| IGA | Males | 2.39 ± 0.89 | 5.44 *** | 2.39 ± 0.85 | 2.88 ** |

| Females | 1.87 ± 0.80 | 2.11 ± 0.74 |

| Variables | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender | — | — | 1 | ||||

| 2. FoC-19 (T1) | 2.09 | 0.87 | 0.03 | 1 | |||

| 3. Loneliness (T2) | 2.00 | 0.53 | 0.05 | 0.29 ** | 1 | ||

| 4. Depression (T2) | 1.53 | 0.62 | −0.11 | 0.28 ** | 0.42 ** | 1 | |

| 5. IGA (T3) | 2.22 | 0.80 | −0.17 ** | 0.20 ** | 0.28 ** | 0.38 ** | 1 |

| χ2/df | CFI | TLI | SRMR | RMSEA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. FoC-19 scale | 3.04 | 0.97 | 0.94 | 0.032 | 0.079 |

| 2. Loneliness scale | 2.24 | 0.96 | 0.94 | 0.041 | 0.063 |

| 3. PHQ-9 | 2.92 | 0.95 | 0.93 | 0.027 | 0.078 |

| 4. IGA scale | 2.75 | 0.95 | 0.94 | 0.036 | 0.074 |

| Predictors | Model 1 (Loneliness) | Model 2 (Depression) | Model 3 (IGA) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | t | 95% CI | β | t | 95% CI | β | t | 95% CI | |

| SES | 0.11 | 0.92 | [−0.13, 0.34] | −0.06 | −0.57 | [−0.28, 0.16] | −0.22 * | −2.02 | [−0.44, −0.01] |

| Age | 0.12 | 2.23 | [0.01, 0.23] | −0.07 | −1.47 | [−0.17, 0.03] | −0.01 | −0.31 | [−0.12, 0.08] |

| Hukou | −0.17 | −1.40 | [−0.41, 0.07] | −0.03 | −0.29 | [−0.26, 0.19] | −0.26 | −2.31 | [−0.49, −0.04] |

| FoC-19 T1 | 0.30 *** | 5.12 | [0.18, 0.41] | 0.19 *** | 3.40 | [0.08, 0.31] | 0.19 * | 2.46 | [0.04, 0.35] |

| Loneliness T2 | 0.37 *** | 6.21 | [0.25, 0.49] | 0.13 * | 2.30 | [0.01, 0.25] | |||

| Depression T2 | 0.18 * | 2.19 | [0.02, 0.35] | ||||||

| Gender | −0.31 ** | −2.66 | [−0.52, −0.08] | ||||||

| FC-19 × Gender | −0.27 * | −2.42 | [−0.49, −0.05] | ||||||

| R2 | 0.12 | 0.23 | 0.23 | ||||||

| F | 8.64 *** | 14.58 *** | 8.13 *** | ||||||

| Hypotheses | Research Hypothesis Statement | Results |

|---|---|---|

| H1 | FoC-19 may be positively associated with subsequent IGA. | Supported |

| H2 | Loneliness independently mediates the link between FoC-19 and IGA. | Supported |

| H3 | Depression independently mediates the link between FoC-19 and IGA. | Supported |

| H4 | Loneliness and depression sequentially mediate the link between FoC-19 and IGA. | Supported |

| H5a | Gender moderates the effect of FoC-19 on IGA. | Supported |

| H5b | Gender moderates the effect of loneliness on IGA. | Not supported |

| H5c | Gender moderates the effect of depression on IGA. | Not supported |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, Q.; Gao, B.; Wu, Y.; Ning, B.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, F. Gender Differences in the Longitudinal Linkages between Fear of COVID-19 and Internet Game Addiction: A Moderated Multiple Mediation Model. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 675. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14080675

Liu Q, Gao B, Wu Y, Ning B, Xu Y, Zhang F. Gender Differences in the Longitudinal Linkages between Fear of COVID-19 and Internet Game Addiction: A Moderated Multiple Mediation Model. Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 14(8):675. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14080675

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Qing, Bin Gao, Yuedong Wu, Bo Ning, Yufei Xu, and Fuyou Zhang. 2024. "Gender Differences in the Longitudinal Linkages between Fear of COVID-19 and Internet Game Addiction: A Moderated Multiple Mediation Model" Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 8: 675. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14080675

APA StyleLiu, Q., Gao, B., Wu, Y., Ning, B., Xu, Y., & Zhang, F. (2024). Gender Differences in the Longitudinal Linkages between Fear of COVID-19 and Internet Game Addiction: A Moderated Multiple Mediation Model. Behavioral Sciences, 14(8), 675. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14080675