Callous–Unemotional Traits and Conduct Problems in Children: The Role of Strength and Positive Characteristics

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Instruments and Measures

2.2.1. Inventory of Callous–Unemotional Traits—Teacher (ICU-Teacher; [59,60]; Portuguese Version Developed by Figueiredo et al. [61,62])

2.2.2. Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ; Goodman et al. [63])

2.2.3. Social–Emotional Assets and Resilience Scale—Teacher Form (SEARS-T; [58])

2.3. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

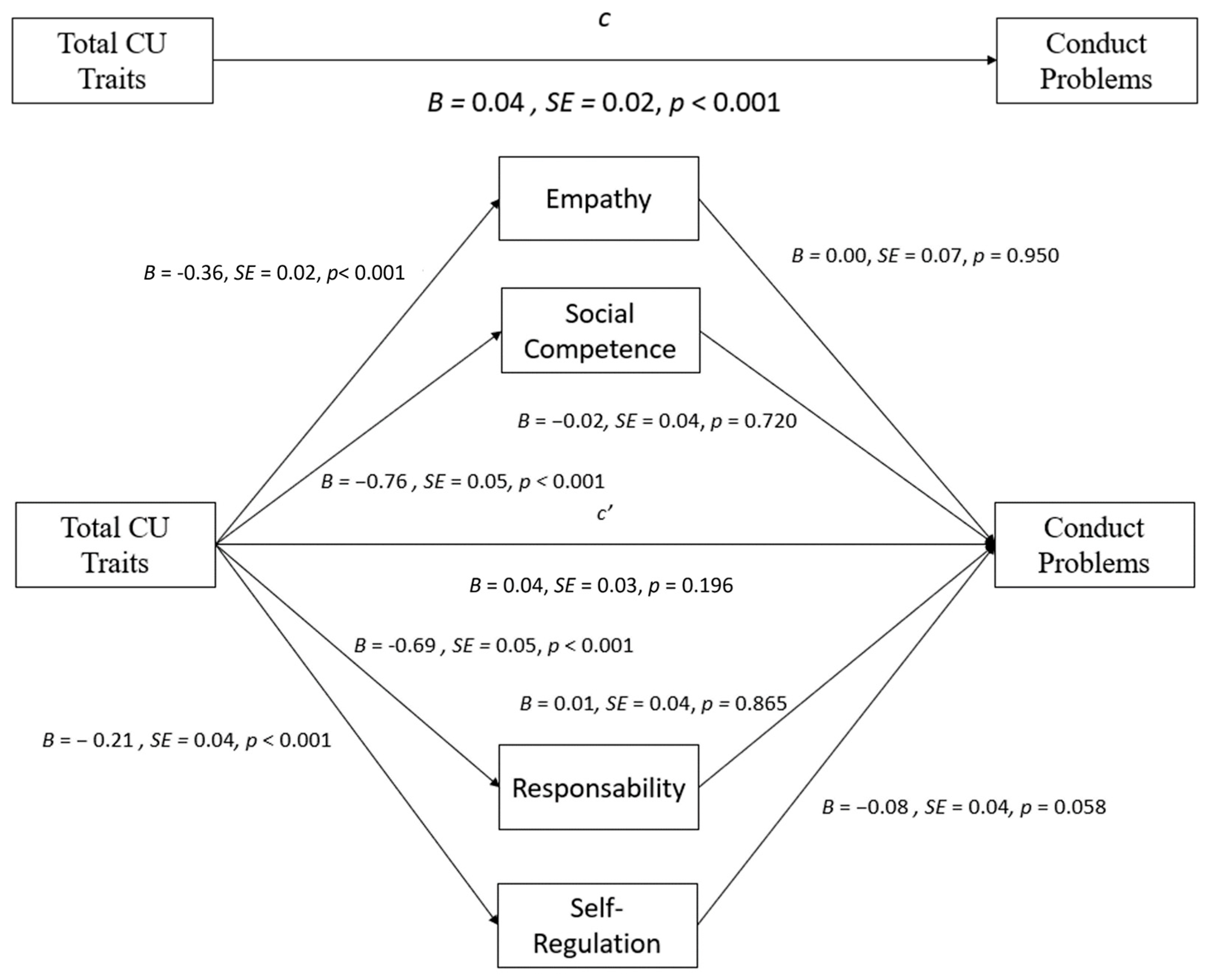

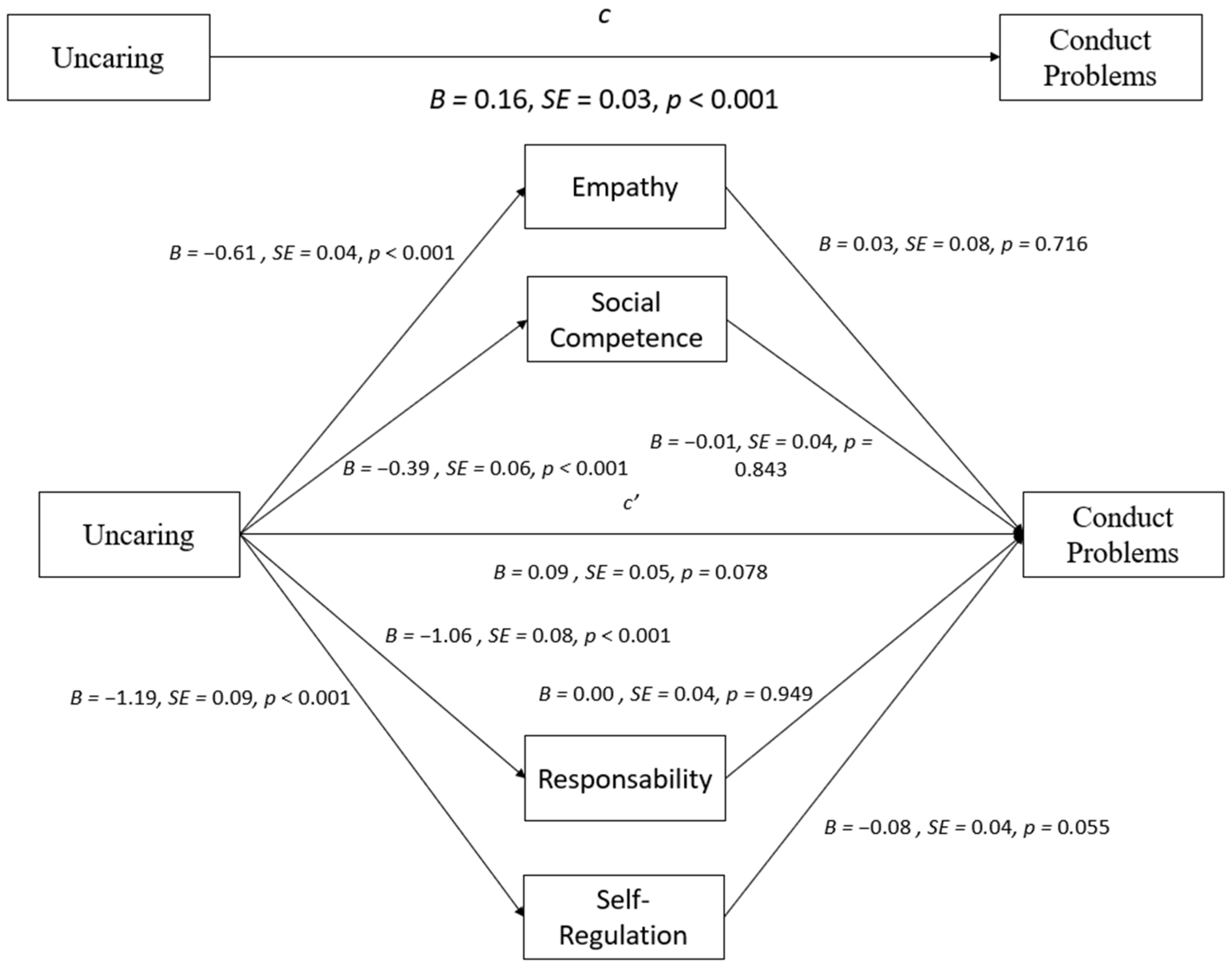

Mediation Effects of Strength and Positive Characteristics

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cooke, D.; Michie, C.; Hart, S.; Clark, D. Reconstructing psychopathy: Clarifying the significance of antisocial and socially deviant behavior in the diagnosis of psychopathic personality disorder. J. Personal. Disord. 2004, 18, 337–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrington, D. The importance of child and adolescent psychopathy. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2005, 33, 489–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frick, P.J.; Stickle, T.R.; Dandreaux, D.M.; Farrell, J.M.; Kimonis, E.R. Callous–unemotional traits in predicting the severity and stability of conduct problems and delinquency. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2005, 33, 471–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frick, P.J.; White, S.F. Research Review: The importance of callous-unemotional traits for developmental models of aggressive and antisocial behavior. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2008, 49, 359–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munoz, L.C.; Frick, P.J. The reliability, stability, and predictive utility of the self-report version of the antisocial process screening device. Scand. J. Psychol. 2007, 48, 299–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obradovic, J.; Pardini, D.; Long, J.D.; Loeber, R. Measuring interpersonal callousness in boys from childhood to adolescence: An examination of longitudinal invariance and temporal stability. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2007, 36, 276–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frick, P.J.; Marsee, M.A. Psychopathy and developmental pathways to antisocial behavior in youth. In The Handbook of Psychopathy; Patrick, C.J., Ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 353–375. [Google Scholar]

- Frick, P.J.; Cornell, A.H.; Barry, C.T.; Bodin, S.D.; Dane, H.E. Callous-unemotional traits and conduct problems in the prediction of conduct problem severity, aggression, and self-report of delinquency. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2003, 31, 457–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyman, D.R.; Caspi, A.; Moffitt, T.E.; Raine, A.; Loeber, R.; Stouthamer-Loeber, M. Adolescent psychopathy and the big five: Results from two samples. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2007, 33, 431–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontaine, N.M.G.; McCrory, E.J.P.; Boivin, M.; Moffitt, T.E.; Viding, E. Predictors and outcomes of joint trajectories of callous-unemotional traits and conduct problems in childhood. J. Abnorm. Child Psychiatry 2011, 120, 730–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frick, P.; Ray, J.; Thorton, L.; Kahn, R. Can Callous–Unemotional traits enhance the understanding, diagnosis and treatment of serious conduct problems in children and adolescents? A comprehensive review. Psychol. Bull. J. 2014, 140, 1–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardini, D.A.; Loeber, R. Interpersonal Callousness trajectories across adolescence: Early social influences and adult outcomes. Crim. Justice Behav. 2008, 35, 173–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fontaine, N.M.; Rijsdijk, F.V.; McCrory, E.J.; Viding, E. Etiology of different developmental trajectories of Callous-Unemotional traits. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2010, 49, 656–664. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Klingzell, I.; Fanti, K.A.; Colins, O.F.; Frogner, L.; Andershed, A.K.; Andershed, H. Early childhood trajectories of conduct problems and Callous-Unemotional traits: The role of fearlessness and psychopathic personality dimensions. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2015, 27, 236–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brazil, I.A. Considering new insights into antisociality and psychopathy. Lancet Psychiatry 2015, 2, 115–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Fanti, K.A. Individual, social, and behavioral factors associated with co-occurring conduct problems and callous-unemotional traits. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2013, 41, 811–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garmezy, N. Vulnerability and resilience. In Studying Lives through time: Personality and Development; Funder, D.C., Parke, R.D., Tomlinson-Keasey, C., Widaman, K., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 1993; pp. 377–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirby, L.; Fraser, M. Risk and resilience in childhood. In Risk and Resilience in Childhood: An Ecological Perspective; Fraser, M., Ed.; NASW: Washington, DC, USA, 1997; pp. 10–33. [Google Scholar]

- Seligman, M.; Csikszentmihalyi, M. Positive psychology: An introduction. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suldo, S.M.; Shaffer, E.J. Looking beyond psychopathology: The dual-factor model of mental health in youth. Sch. Psychol. Rev. 2008, 37, 52–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecchiotti, S. Kindergarten: An Overlooked Educational Policy Priority. Soc. Policy Rep. 2003, 17, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denham, S.A.; Bassett, H.H.; Zinsser, K. Early Childhood Teachers as Socializers of Young Children’s Emotional Competence. Early Child. Educ. J. 2012, 40, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, K.H.; Squires, J. Cultural adaptation of a parent completed social emotional screening instrument for young children: Ages and stages questionnaire-social emotional. Early Hum. Dev. 2012, 88, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yates, T.; Ostrosky, M.M.; Cheatham, G.A.; Fettig, A.; Shaffer, L.; Santos, R.M. Research Synthesis on Screening and Assessing Social and Emotional Competence. Center on the Social Emotional Foundations of Early Learning at Vanderbilt University, 2008. Available online: http://csefel.vanderbilt.edu/documents/rs_screening_assessment.pdf (accessed on 3 February 2024).

- Granic, I.; Patterson, G.R. Toward a comprehensive model of antisocial development: A dynamic systems approach. Psychol. Rev. 2006, 113, 101–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salekin, R.T. Psychopathy in childhood: Why should we care about grandiose-manipulative and daring-impulsive traits? Br. J. Psychiatry 2016, 209, 189–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; APA: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kashdan, T.B.; Rottenberg, J. Psychological flexibility as a fundamental aspect of health. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2010, 30, 865–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCabe, L.A.; Cunnington, M.; Brooks-Gunn, J. The development of self-regulation in young children. In Handbook of the Self-Regulation: Research Theory and Applications; Baumeister Ve, R.F., Vohs, K.D., Eds.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2004; pp. 341–357. [Google Scholar]

- McClelland, M.M.; Cameron, C.E. Self-regulation in early childhood: Improving conceptual clarity and developing ecologically valid measures. Child Dev. Perspect. 2012, 6, 136–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinberg, L.; Albert, D.; Cauffman, E.; Banich, M.; Graham, S.; Woolard, J. Age differences in sensation seeking and impulsivity as indexed by behavior and self-report: Evidence for a dual systems model. Dev. Psychol. 2008, 44, 1764–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skibbe, L.E.; Connor, C.M.; Morrison, F.J.; Jewkes, A.M. Schooling effects on preschoolers’ self-regulation, early literacy and language growth. Early Child. Res. Q. 2011, 26, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuevas, K.; Rajan, V.; Bryant, L.J. Emergence of executive function in infancy. In Executive Function: Development across the Life Span; Wiebe, S.A., Karbach, J., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2008; pp. 25–42. [Google Scholar]

- Posner, M.I.; Rothbart, M.K. Developing mechanisms of self-regulation. Dev. Psychopthol. 2009, 12, 427–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watson, A.J.; Bell, M.A. Individual differences in ınhibitory control skills at three years of age. Dev. Neuropsychol. 2013, 38, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, S.M.; Wang, T.S. Inhibitory control and emotion regulation in preschool children. Cogn. Dev. 2007, 22, 489–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitebread, D.; Basilio, M. The emergence of early development of self regulation in young children. Profesorado 2012, 116, 15–33. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, M.; Granic, I.; Lamm, C. Behavioral differences in aggressive children linked with neural mechanisms of emotion regulation. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2006, 1094, 164–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cole, P.M.; Martin, S.E.; Dennis, T.A. Emotion regulation as a scientific construct: Methodological challenges and directions for child development research. Child Dev. 2004, 75, 317–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frick, P.J.; Morris, A.S. Temperament and developmental pathways to conduct problems. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2004, 33, 54–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eisenberg, N. Emotion, regulation, and moral development. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2000, 51, 665–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hadjicharalambous, M.Z.; Fanti, K.A. Self regulation, cognitive capacity and risk taking: Investigating heterogeneity among adolescents with callous-unemotional traits. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2017, 49, 331–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wall, T.D.; Frick, P.J.; Fanti, K.A.; Kimonis, E.R.; Lordos, A. Factors differentiating callous-unemotional children with and without conduct problems. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2016, 57, 976–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roelofs, A. Goal-referenced selection of verbal action: Modeling attentional control in the Stroop task. Psychol. Rev. 2003, 110, 88–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carver, C.S.; Scheier, M.F. On the Self-Regulation of Behavior; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Q.; Chen, S.H.; Main, A. Commonalities and differences in the research on children’s effortful control and executive function: A call for an integrated model of self-regulation. Child Dev. Perspect. 2012, 6, 112–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornstein, M.H.; Hahn, C.-S.; Haynes, O.M. Social competence, externalizing, and internalizing behavioral adjustment from early childhood through early adolescence: Developmental cascades. Dev. Psychopathol. 2010, 22, 717–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roos, S.; Hodges, E.V.; Salmivalli, C. Do guilt-and shame-proneness differentially predict prosocial, aggressive, and withdrawn behaviors during early adolescence? Dev. Psychol. 2014, 50, 941–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallquist, J.; Eisenberg, N.; Spinrad, T.L.; Eggum, N.D.; Gaertner, B.M. Assessment of preschoolers’ positive empathy: Concurrent and longitudinal relations with positive emotion, social competence, and sympathy. J. Posit. Psychol. 2009, 4, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howes, C. Social competence with peers in young children: Developmental sequences. Dev. Rev. 1987, 7, 252–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimonis, E.R.; Frick, P.J.; Boris, N.W.; Smyke, A.T.; Cornell, A.H.; Farrell, J.M.; Zeanah, C.H. Callous-unemotional features, behavioral inhibition, and parenting: Independent predictors of aggression in a high-risk preschool sample. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2006, 15, 741–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadds, M.R.; Fraser, J.; Frost, A.; Hawes, D.J. Disentangling the underlying dimensions of psychopathy and conduct problems in childhood: A community study. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2005, 73, 400–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hay, D.F.; Payne, A.; Chadwick, A. Peer relations in childhood. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2004, 45, 84–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Izard, C.E.; Fine, S.; Mostow, A.; Trentacosta, C.; Campbell, J. Emotional processes in normal and abnormal development and preventive intervention. Dev. Psychopathol. 2002, 14, 761–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arsenio, W.F.; Cooperman, S.; Lover, A. Afective predictors of preschoolers’ aggression and peer acceptance: Direct and indirect effects. Dev. Psychopathol. 2000, 36, 438–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Castro, B.O.; Bosch, J.D.; Veerman, J.W.; Koops, W. The effects of emotion regulation, attribution, and delay prompts on aggressive boys’ social problem solving. Cogn. Ther. Res. 2003, 27, 153–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLisi, M.; Vaughn, M.G. Foundation for a temperament-based theory of antisocial behavior and criminal justice system involvement. J. Crim. Justice 2014, 42, 10–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merrell, K. Social Emotional Assets and Resilience Scales; Professional Manual; PAR: Lutz, FL, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Essau, C.A.; Sasagawa, S.; Frick, P.J. Callous-unemotional traits in a community sample of adolescents. Assessment 2006, 13, 454–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frick, P.J. The Inventory of Callous-Unemotional Traits (Unpublished Rating Scale); University of New Orleans: New Orleans, LA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Figueiredo, P.; Moreira, D.; Ramião, E.; Barroso, R.; Barbosa, F. Psychometric properties of the Portuguese teacher-version of the inventory of Callous-Unemotional traits. Clin. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2022, 27, 135910452110701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Figueiredo, P.; Ramião, E.; Moreira, D.; Barroso, R.; Barbosa, F. Psychometric properties of the Portuguese teacher-version of the Inventory of Callous-Unemotional Traits in Preschoolers. Análise Psicológica 2023, 41, 127–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, R.; Meltzer, H.; Bailey, V. The strengths and difficulties questionnaire: A pilot study on the validity of the self-report version. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 1998, 7, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fleitlich, B.; Cortázar, P.G.; Goodman, R. Questionário de capacidades e dificuldades (SDQ). Infanto-Rev. Neuropsiquiatr. Infância Adolesc. 2000, 8, 44–50. [Google Scholar]

- Marzocchi, G.M.; Capron, C.; Di Pietro, M.; Duran Tauleria, E.; Duyme, M.; Frigerio, A.; Gaspar, M.F.; Hamilton, H.; Pithon, G.; Simões, A.; et al. The use of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) in Southern European countries. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2004, 13, ii40–ii46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Figueiredo, P.; Azeredo, A.; Barroso, R.; Barbosa, F. Psychometric Properties of Teacher Report of Social-Emotional Assets and Resilience Scale in Preschoolers and Elementary School Children. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 2020, 42, 799–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.Y. Statistical notes for clinical researchers: Assessing normal distribution using skewness and kurtosis. Restor. Dent. Endod. 2013, 38, 52–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lynam, D.R.; Caspi, A.; Moffitt, T.E.; Loeber, R.; Stouthamer-Loeber, M. Longitudinal evidence that psychopathy scores in early adolescence predict adult psychopathy. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2008, 116, 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salekin, R.T. Research Review: What do we know about psychopathic traits in children? J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2017, 58, 1180–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezpeleta, L.; de la Osa, N.; Granero, R.; Penelo, E.; Domènech, J.M. Inventory of Callous-Unemotional traits in a community sample of preschoolers. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2013, 42, 91–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimonis, E.; Goulter, N.; Hawes, D.; Wilbur, R.; Groer, M. Neuroendocrine factors distinguish juvenile psychopathy variants. Dev. Psychobiol. 2016, 59, 161–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fanti, K.A.; Colins, O.F.; Andershed, H.; Sikki, M. Stability and change in Callous-Unemotional traits: Longitudinal associations with potential individual and contextual risk and protective factors. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2016, 87, 62–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flouri, E.; Tzavidis, N.; Kallis, C. Area and family effects on the psychopathology of the Millennium Cohort Study children and their older siblings. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2010, 51, 152–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Longman, T.; Hawes, D.J.; Kohlhoff, J. Callous–Unemotional Traits as Markers for Conduct Problem Severity in Early Childhood: A Meta-analysis. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2015, 47, 326–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, N.; Shavelson, R. Generalizability Theory: Overview. In Encyclopedia of Statistics in Behavioral Science; Everitt, B., Howell, D., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luke, D. Multilevel Modeling (Quantitative Applications in the Social Sciences); SAGE Publications, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- De Los Reyes, A.; Augenstein, T.M.; Wang, M.; Thomas, S.A.; Drabick, D.A.; Burgers, D.E.; Rabinowitz, J. The validity of the multi-informant approach to assessing child and adolescent mental health. Psychol. Bull. 2015, 141, 858–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Los Reyes, A.; Kazdin, A.E. Informant discrepancies in the assessment of childhood psychopathology: A critical review, theoretical framework, and recommendations for further study. Psychol. Bull. 2005, 131, 483–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valo, S.; Tannock, R. Diagnostic instability of DSM-IV ADHD subtypes: Effects of informant source, instrumentation, and methods for combining symptom reports. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2010, 39, 749–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abikoff, H.; Courtney, M.; Pelham, W.E.; Koplewicz, H.S. Teachers’ ratings of disruptive behaviors: The influence of halo effects. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 1993, 21, 519–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curhan, K.B.; Levine, C.S.; Markus, H.R.; Kitayama, S.; Park, J.; Karasawa, M.; Park, J.; Karasawa, M.; Kawakami, N.; Love, G.; et al. Subjective and objective hierarchies and their relations to psychological well-being: A US/Japan comparison. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 2014, 5, 855–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, A.K.; Imami, L.; Stanton, S.C.E.; Slatcher, R.B. Affective processes as mediators of links between close relationships and physical health. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 2018, 12, e12408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monahan, K.C.; Steinberg, L.; Cauffman, E.; Mulvey, E.P. Trajectories of antisocial behavior and psychosocial maturity from adolescence to young adulthood. Dev. Psychol. 2009, 45, 1654–1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitcomb, S. Behavioral, Social, and Emotional Assessment of Children and Adolescents; Routledge: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Diamond, A.; Lee, K. Interventions Shown to Aid Executive Function Development in Children 4 to 12 Years Old. Science 2011, 333, 959–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomporowski, P.D.; McCullick, B.; Pendleton, D.M.; Pesce, C. Exercise and children’s cognition: The role of exercise characteristics and a place for metacognition. J. Sport Health Sci. 2015, 4, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Possible Range | N | Min | Max | Mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | – | 236 | 3 | 11 | 7.14 (1.99) |

| Education | – | – | – | – | |

| Kindergarten | – | 69 | – | – | – |

| Elementary School | – | 167 | – | – | – |

| Total CU traits | (0–33) | 215 | 0 | 27 | 8.76 (5.37) |

| Callousness | (0–18) | 215 | 0 | 14 | 2.10 (2.89) |

| Uncaring | (0–15) | 215 | 0 | 15 | 6.65 (3.31) |

| Conduct Problems | (0–10) | 223 | 0 | 8 | 1.77 (1.62) |

| Self-Regulation | (0–39) | 216 | 0 | 34 | 21.49 (5.60) |

| Empathy | (0–48) | 216 | 2 | 18 | 11. 19 (2.71) |

| Social Competence | (0–39) | 216 | 0 | 34 | 11.20 (3.05) |

| Responsibility | (0–30) | 216 | 1 | 30 | 18.95 (5.13) |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Total of CU traits | – | |||||||

| 2. Callousness | 0.85 ** | – | ||||||

| 3. Uncaring | 0.89 ** | 0.50 ** | –– | |||||

| 4. Conduct Problems | 0.32 ** | 0.21 ** | 0.334 ** | – | ||||

| 5. Self-Regulation | −0.74 ** | −0.56 ** | −0.71 ** | −0.35 ** | – | |||

| 6. Empathy | −0.72 ** | −0.59 ** | −0.74 ** | −0.30 ** | 0.82 ** | – | ||

| 7. Social Competence | −0.39 ** | −0.24 ** | −0.43 ** | −0.21 ** | 0.55 ** | 0.52 ** | – | |

| 8. Responsibility | −0.74 ** | −0.58 ** | −0.70 ** | −0.31 ** | 0.84 ** | 0.80 ** | 0.55 ** | – |

| Independent Variable | Mediated Effect | Point Estimate | SE | BCa 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total CU traits | ||||

| Empathy | −0.002 | 0.023 | [−0.048, 0.044] | |

| Responsibility | −0.005 | 0.030 | [−0.059, 0.056] | |

| Self-Regulation | 0.057 | 0.034 | [−0.009, 0.124] | |

| Social Competence | 0.003 | 0.011 | [−0.026, 0.016] | |

| Callousness | ||||

| Empathy | 0.008 | 0.030 | [−0.051, 0.067] | |

| Responsibility | 0.005 | 0.044 | [−0.076, 0.095] | |

| Self-Regulation | 0.088 * | 0.046 | [0.005, 0.187] | |

| Social Competence | 0.002 | 0.013 | [−0.035, 0.015] | |

| Uncaring | ||||

| Empathy | −0.017 | 0.039 | [−0.098, 0.056] | |

| Responsibility | −0.003 | 0.047 | [−0.090, 0.093] | |

| Self-Regulation | 0.089 | 0.051 | [−0.011, 0.191] | |

| Social Competence | 0.003 | 0.020 | [−0.051, 0.028] | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Figueiredo, P.; Azeredo, A.; Barroso, R.; Barbosa, F. Callous–Unemotional Traits and Conduct Problems in Children: The Role of Strength and Positive Characteristics. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 609. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14070609

Figueiredo P, Azeredo A, Barroso R, Barbosa F. Callous–Unemotional Traits and Conduct Problems in Children: The Role of Strength and Positive Characteristics. Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 14(7):609. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14070609

Chicago/Turabian StyleFigueiredo, Patrícia, Andreia Azeredo, Ricardo Barroso, and Fernando Barbosa. 2024. "Callous–Unemotional Traits and Conduct Problems in Children: The Role of Strength and Positive Characteristics" Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 7: 609. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14070609

APA StyleFigueiredo, P., Azeredo, A., Barroso, R., & Barbosa, F. (2024). Callous–Unemotional Traits and Conduct Problems in Children: The Role of Strength and Positive Characteristics. Behavioral Sciences, 14(7), 609. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14070609