Psychopathic Traits in Adult versus Adolescent Males: Measurement Invariance across the PCL-R and PCL:YV

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. The Four-Factor Model of Psychopathy

1.2. Measurement Invariance

1.3. Current Study

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Procedures

2.4. Measures

2.5. Preliminary Analyses

2.6. Primary Analyses

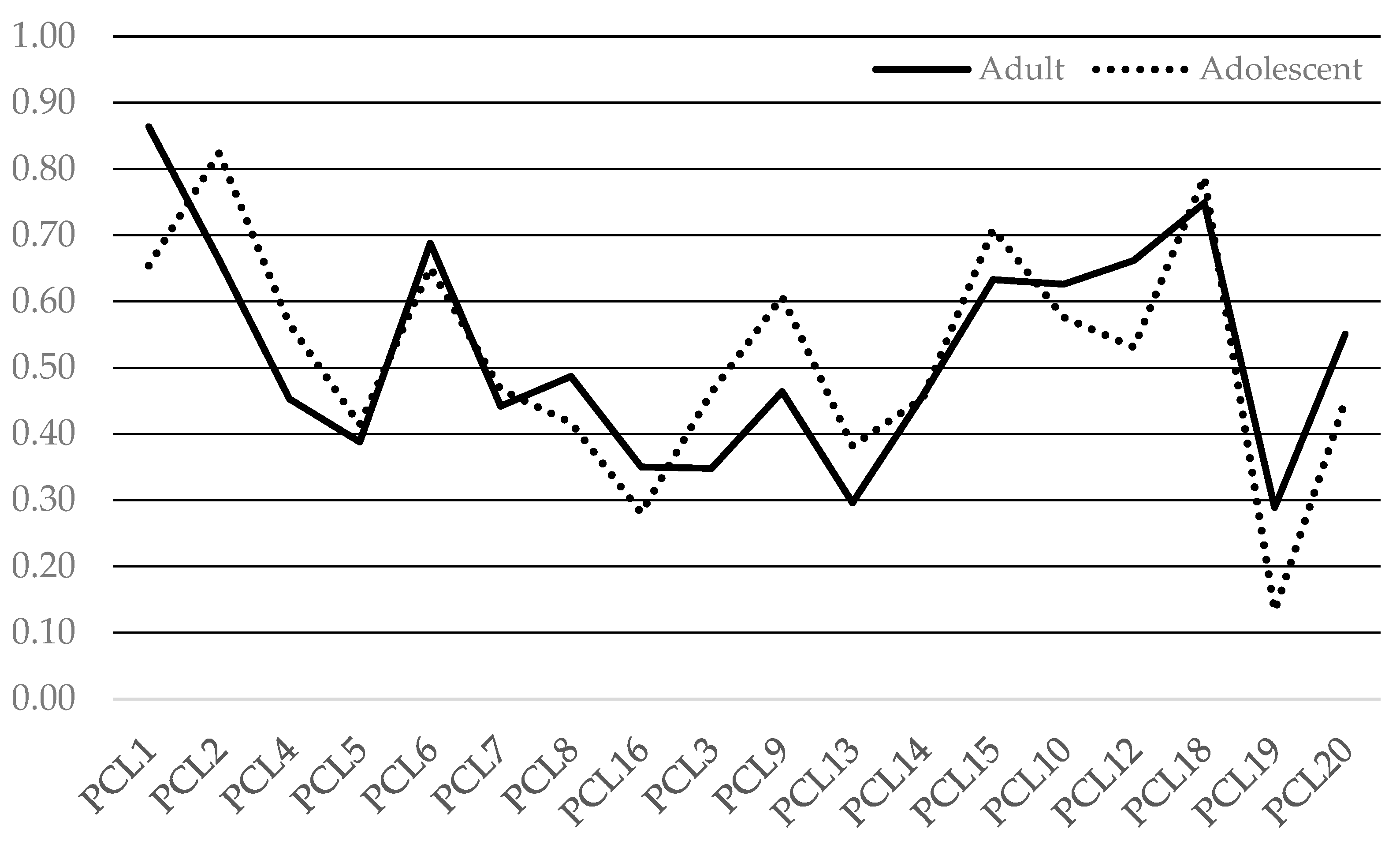

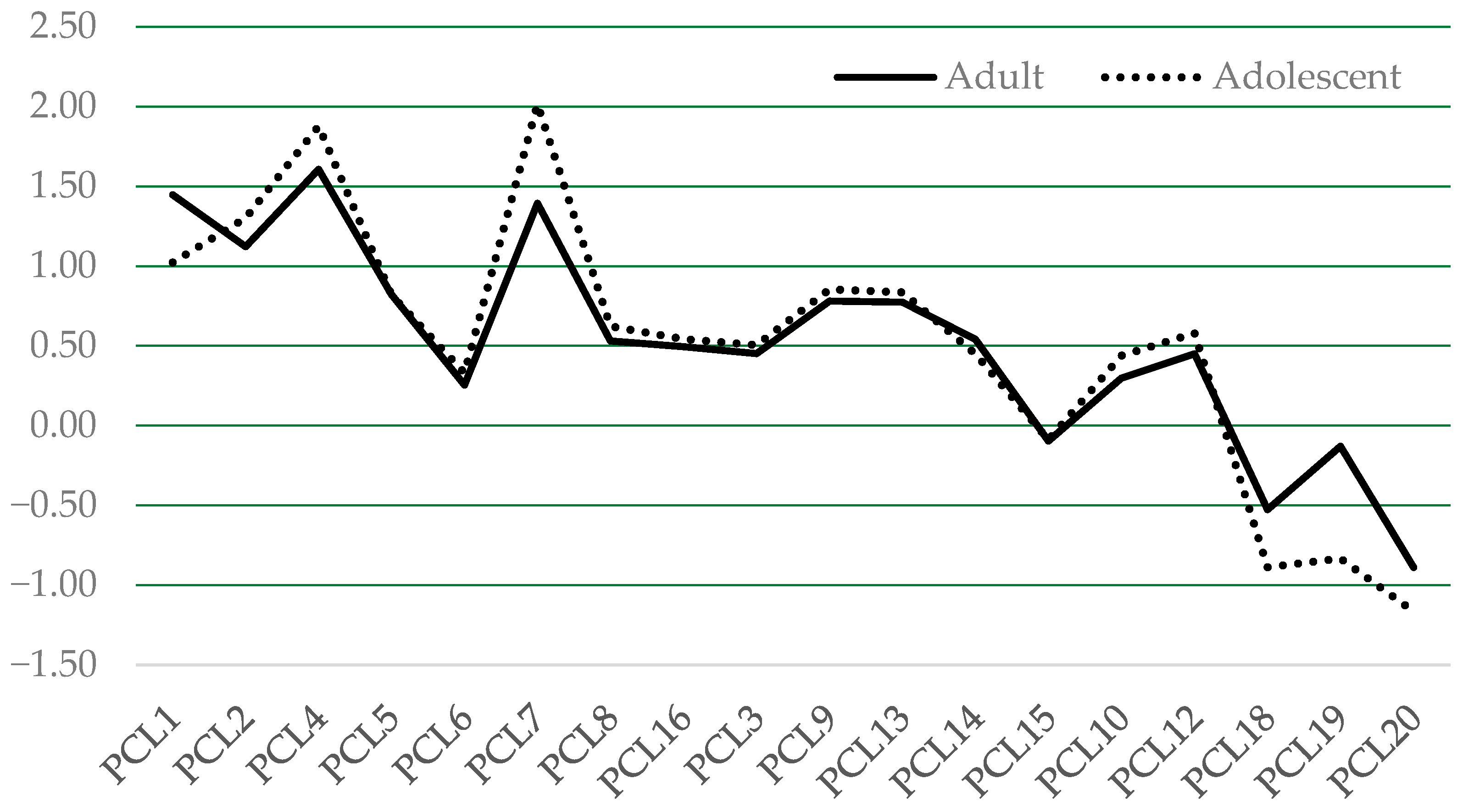

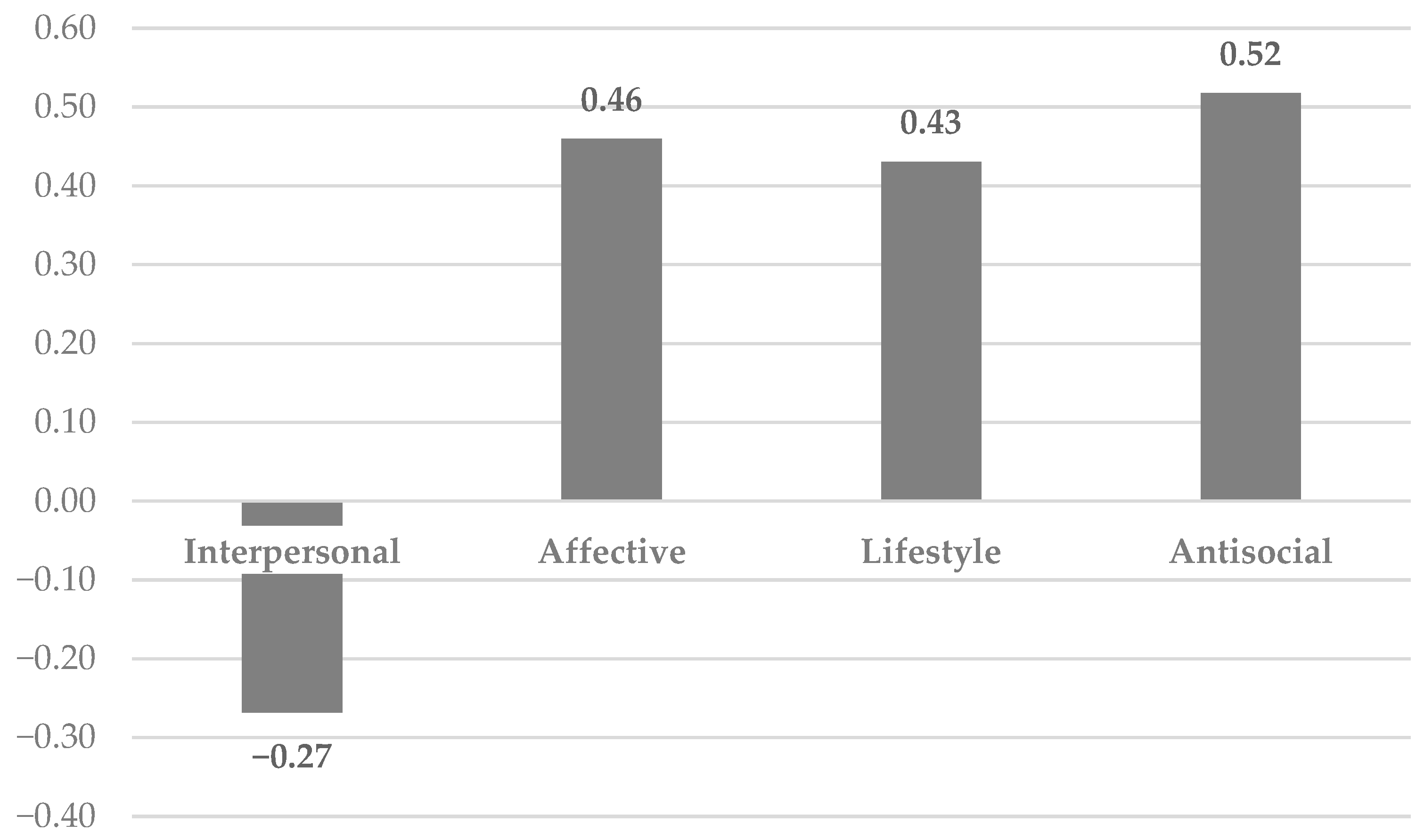

3. Results

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hare, R.D.; Neumann, C.S. Psychopathy as a clinical and empirical construct. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2008, 4, 217–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellamy, N.A.; Neumann, C.S.; Mendez, B.; Batky, B.D.; DeGroot, H.R.; Hare, R.D.; Salekin, R.T. Proposed Specifiers for Conduct Disorder (PSCD): Further validation of the parent-report version in a nationally representative U.S. sample of 10- to 17-year-olds. Psychol. Assess. 2024, 36, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neumann, C.S.; Hare, R.D. Psychopathic traits in a large community sample: Links to violence, alcohol use, and intelligence. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2008, 76, 893–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Brito, S.A.; Forth, A.E.; Baskin-Sommers, A.R.; Brazil, I.A.; Kimonis, E.R.; Pardini, D.; Frick, P.J.; Blair, R.J.R.; Viding, E. Psychopathy. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2021, 7, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garofalo, C.; Neumann, C.S. Psychopathy emotion regulation: Taking stock moving forward. In Routledge International Handbook of Psychopathy and Crime; DeLisi, M., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2018; pp. 76–97. [Google Scholar]

- Hare, R.D.; Neumann, C.S. The role of antisociality in the psychopathy construct: Comment on Skeem and Cooke (2010). Psychol. Assess. 2010, 22, 446–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olver, M.E.; Neumann, C.S.; Sewall, L.A.; Lewis, K.; Hare, R.D.; Wong SC, P. A comprehensive examination of the psychometric properties of the Hare Psychopathy Checklist-Revised in a Canadian multisite sample of indigenous and non-indigenous offenders. Psychol. Assess. 2018, 30, 779–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olver, M.E.; Stockdale, K.C.; Neumann, C.S.; Hare, R.D.; Mokros, A.; Baskin-Sommers, A.; Brand, E.; Folino, J.; Gacono, C.; Gray, N.S.; et al. Reliability and validity of the Psychopathy Checklist-Revised in the assessment of risk for institutional violence: A cautionary note on DeMatteo et al. (2020). Psychol. Public Policy Law 2020, 26, 490–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellingson, J.M.; Littlefield, A.K.; Vergés, A.; Sher, K.J. Psychopathy substance use disorders. In Handbook of Psychopathy, 2nd ed.; Patrick, C.J., Ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 710–731. [Google Scholar]

- Loney, B.R.; Taylor, J.; Butler, M.A.; Iacono, W.G. Adolescent psychopathy features: 6-Year temporal stability and the prediction of externalizing symptoms during the transition to adulthood. Aggress. Behav. 2007, 33, 242–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynam, D.R.; Caspi, A.; Moffitt, T.E.; Loeber, R.; Stouthamer-Loeber, M. Longitudinal evidence that psychopathy scores in early adolescence predict adult psychopathy. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2007, 116, 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadds, M.R.; Hawes, D.J.; Frost, A.D.; Vassallo, S.; Bunn, P.; Hunter, K.; Merz, S. Learning to ‘talk the talk: The relationship of psychopathic traits to deficits in empathy across childhood. J. Child Psychol. Ppsychiatry Allied Discip. 2009, 50, 599–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waller, R.; Wagner, N.J.; Barstead, M.G.; Subar, A.; Petersen, J.L.; Hyde, J.S.; Hyde, L.W. A meta-analysis of the associations between callous-unemotional traits and empathy, prosociality, and guilt. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2020, 75, 101809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, A.B.; Fleming, G.E.; Kaouar, S.; Kimonis, E.R. The measure of empathy in early childhood: Testing the reliability, validity, and clinical utility of scores in early childhood. Psychol. Assess. 2023, 35, 791–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lima, F.F.D.; Osório, F.L. Empathy: Assessment instruments and psychometric quality—A systematic literature review with a meta-analysis of the past ten years. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 781346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sesso, G.; Brancati, G.E.; Fantozzi, P.; Inguaggiato, E.; Milone, A.; Masi, G. Measures of empathy in children and adolescents: A systematic review of questionnaires. World J. Psychiatry 2021, 11, 876–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viding, E.; McCrory, E.; Baskin-Sommers, A.; DeBrito, S.; Frick, P. An ‘embedded brain’ approach to understanding antisocial behaviour. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2023, 28, 159–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, C.S.; Wampler, M.; Taylor, J.; Blonigen, D.M.; Iacono, W.G. Stability and invariance of psychopathic traits from late adolescence to young adulthood. J. Res. Personal. 2011, 45, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neumann, C.S.; Hare, R.D.; Pardini, D.A. Antisociality and the construct of psychopathy: Data from across the globe. J. Personal. 2015, 83, 678–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, E.; Xu, C.; Neumann, C.S. Assessment of psychopathy among justice-involved adult males with low versus average intelligence: Differential links to violent offending. Psychol. Assess. 2024, 36, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vitacco, M.J.; Neumann, C.S.; Jackson, R.L. Testing a four-factor model of psychopathy and its association with ethnicity, gender, intelligence, and violence. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2005, 73, 466–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hare, R.D. The Hare Psychopathy Checklist-Revised, 2nd ed.; Multi-Health Systems: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hart, S.D.; Cox, D.N.; Hare, R.D. Manual for the Psychopathy Checklist: Screening Version (PCL:SV); Multi-Health Systems: Toronto, ON, Canada, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Forth, A.E.; Kosson, D.; Hare, R.D. The Hare Psychopathy Checklist: Youth Version; Multi-Health Systems: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Forth, A.E.; Brazil, K.J. Psychopathy Checklist: Youth Version (PCL:YV). In The SAGE Encyclopedia of Criminal Psychology; Morgan, R.D., Ed.; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2019; pp. 1193–1196. [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie, S.M.; Jones, A.; Garofalo, C. Psychopathy and dangerousness: An umbrella review and meta-analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2023, 100, 102240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, C.S.; Schmitt, D.S.; Carter, R.; Embley, I.; Hare, R.D. Psychopathic traits in females and males across the globe. Behav. Sci. Law 2012, 30, 557–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuvblad, C.; Bezdjian, S.; Raine, A.; Baker, L.A. The heritability of psychopathic personality in 14-to 15-year-old twins: A multirater, multimeasure approach. Psychol. Assess. 2014, 26, 704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lynam, D.R.; Miller, D.J.; Vachon, D.; Loeber, R.; Stouthamer-Loeber, M. Psychopathy in adolescence predicts official reports of offending in adulthood. Youth Violence Juv. Justice 2009, 7, 189–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gretton, H.M.; Hare, R.D.; Catchpole, R.E.H. Psychopathy and offending from adolescence to adulthood: A 10-year follow-up. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2004, 72, 636–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lussier, P.; McCuish, E.; Corrado, R. Psychopathy and the prospective prediction of adult offending through age 29: Revisiting unfulfilled promises of developmental criminology. J. Crim. Justice 2022, 80, 101770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosson, D.S.; Cyterski, T.D.; Steuerwald, B.L.; Neumann, C.S.; Walker-Matthews, S. The reliability and validity of the Psychopathy Checklist: Youth Version (PCL:YV) in nonincarcerated adolescent males. Psychol. Assess. 2002, 14, 97–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCuish, E.C.; Corrado, R.; Lussier, P.; Hart, S.D. Psychopathic traits and offending trajectories from early adolescence to adulthood. J. Crim. Justice 2014, 42, 66–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, C.S.; Jones, D.N.; Paulhus, D.L. Examining the Short Dark Tetrad (SD4) across models, correlates, and gender. Assessment 2022, 29, 651–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, R.L.; Neumann, C.S.; Vitacco, M.J. Impulsivity, anger, and psychopathy: The moderating effect of ethnicity. J. Personal. Disord. 2007, 21, 289–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolt, D.M.; Hare, R.D.; Vitale, J.E.; Newman, J.P. A Multigroup Item Response Theory Analysis of the Psychopathy Checklist-Revised. Psychol. Assess. 2004, 16, 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolt, D.M.; Hare, R.D.; Neumann, C.S. Score metric equivalence of the Psychopathy Checklist–Revised (PCL-R) across criminal offenders in North America and the United Kingdom: A critique of Cooke, Michie, Hart, and Clark (2005) and new analyses. Assessment 2007, 14, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawes, S.W.; Byrd, A.L.; Kelley, S.E.; Gonzalez, R.; Edens, J.F.; Pardini, D.A. Psychopathic features across development: Assessing longitudinal invariance among Caucasian and African American youths. J. Res. Personal. 2018, 73, 180–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCuish, E.C.; Mathesius, J.R.; Lussier, P.; Corrado, R.R. The cross-cultural generalizability of the psychopathy checklist: Youth version for adjudicated Indigenous youth. Psychol. Assess. 2018, 30, 192–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaffer, C.; McCuish, E.; Corrado, R.R.; Behnken, M.P.; DeLisi, M. Psychopathy and violent misconduct in a sample of violent young offenders. J. Crim. Justice 2015, 43, 321–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, S.; Cauffman, E.; Miller, J.D.; Mulvey, E. Investigating different factor structures of the psychopathy checklist: Youth version: Confirmatory factor analytic findings. Psychol. Assess. 2006, 18, 33–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vincent, G.M.; Odgers, C.L.; McCormick, A.V.; Corrado, R.R. The PCL:YV and recidivism in male and female juveniles: A follow-up into young adulthood. Int. J. Law Psychiatry 2008, 31, 287–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kosson, D.S.; Neumann, C.S.; Forth, A.E.; Salekin, R.T.; Hare, R.D.; Krischer, M.K.; Sevecke, K. Factor structure of the hare psychopathy checklist: Youth version (PCL: YV) in adolescent females. Psychol. Assess. 2013, 25, 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simões, M.; Gonçalves, R.A. The problem of adolescent psychopathy: The downward extension of adult psychopathy. In Psychopathy: New Updates on an Old Phenomenon; Durbano, F., Ed.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2017; pp. 57–76. [Google Scholar]

- Edens, J.F.; Marcus, D.K.; Lilienfeld, S.O.; Poythress, N.G., Jr. Psychopathic, not psychopath: Taxometric evidence for the dimensional structure of psychopathy. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2006, 115, 131–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murrie, D.C.; Marcus, D.K.; Douglas, K.S.; Lee, Z.; Salekin, R.T.; Vincent, G. Youth with psychopathy features are not a discrete class: A taxometric analysis. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry Allied Discip. 2007, 48, 714–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vachon, D.D.; Lynam, D.R.; Schell, S.E.; Dryburgh NS, J.; Costa, P.T. Teenagers as temporary psychopaths? Stability in normal adolescent personality suggests otherwise. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2018, 131, 117–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynam, D.R.; Loeber, R.; Stouthamer-Loeber, M. The stability of psychopathy from adolescence into adulthood: The search for moderators. Crim. Justice Behav. 2008, 35, 228–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seagrave, D.; Grisso, T. Adolescent development and the measurement of juvenile psychopathy. Law Hum. Behav. 2002, 26, 219–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limitations on Dispositional Judgments; Modification; Termination; or Extension of Court Orders. NM Stat § 32A-2-23. 2023. Available online: https://casetext.com/statute/new-mexico-statutes-1978/chapter-32a-childrens-code/article-2-delinquency/section-32a-2-23-limitations-on-dispositional-judgments-modification-termination-or-extension-of-court-orders (accessed on 9 May 2024).

- Baskin-Sommers, A.R.; Neumann, C.S.; Cope, L.M.; Kiehl, K.A. Latent-variable modeling of brain gray-matter volume and psychopathy in incarcerated offenders. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2016, 125, 811–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neumann, C.S.; Kosson, D.S.; Forth, A.E.; Hare, R.D. Factor structure of the Psychopathy Checklist: Youth Version (PCL:YV) in incarcerated adolescents. Psychol. Assess. 2006, 18, 142–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmitt, N. Uses and abuses of coefficient alpha. Psychol. Assess. 1996, 8, 350–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, H.W.; Nagengast, B.; Morin, A.J. Measurement invariance of big-five factors over the life span: ESEM tests of gender, age, plasticity, maturity, and la dolce vita effects. Dev. Psychol. 2013, 49, 1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muthén, L.K.; Muthén, B.O. Mplus User’s Guide, 8th ed.; Muthén & Muthén: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1998–2017. [Google Scholar]

- West, S.G.; Taylor, A.B.; Wu, W. Model fit and model selection in structural equation modeling. In Handbook of Structural Equation Modeling; Hoyle, R.H., Ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 209–231. [Google Scholar]

- Marsh, H.W.; Hau, K.T.; Wen, Z. In search of golden rules: Comment on hypothesis-testing approaches to setting cutoff values for fit indexes and dangers in overgeneralizing Hu and Bentler’s (1999) findings. Struct. Equ. Model. 2004, 11, 320–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, G.W.; Rensvold, R.B. Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Struct. Equ. Model. 2002, 9, 233–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, C.; Liang, X. Sensitivity of fit measures to lack of measurement invariance in exploratory structural equation modeling. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J. 2022, 29, 248–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svetina, D.; Rutkowski, L.; Rutkowski, D. Multiple-group invariance with categorical outcomes using updated guidelines: An illustration using M plus and the lavaan/semtools packages. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J. 2020, 27, 111–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Neumann, C.S.; Hare, R.D. Validating latent profiles of the Psychopathy Checklist-Revised with a large sample of incarcerated men. Personal. Disord. Theory Res. Treat. 2023, 14, 649–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neumann, C.S.; Salekin, R.T.; Commerce, E.; Charles, N.E.; Barry, C.T.; Mendez, B.; Hare, R.D. Proposed Specifiers for Conduct Disorder (PSCD) scale: A Latent Profile Analysis with At-Risk Adolescents. Res. Child Adolesc. Psychopathol. 2024, 52, 369–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viding, E.; Frick, P.J.; Plomin, R. Aetiology of the relationship between callous-unemotional traits and conduct problems in childhood. Br. J. Psychiatry 2007, 190, s33–s38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harpur, T.J.; Hare, R.D. Assessment of psychopathy as a function of age. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 1994, 103, 604–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maurer, J.M.; Edwards, B.G.; Harenski, C.L.; Decety, J.; Kiehl, K.A. Do psychopathic traits vary with age among women? A cross-sectional investigation. J. Forensic Psychiatry Psychol. 2022, 33, 112–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro da Silva, D.; Rijo, D.; Brazão, N.; Paulo, M.; Miguel, R.; Castilho, P.; Vagos, P.; Gilbert, P.; Salekin, R.T. The efficacy of the PSYCHOPATHY. COMP program in reducing psychopathic traits: A controlled trial with male detained youth. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2021, 89, 499. [Google Scholar]

- United States Census Bureau. QuickFacts: New Mexico. Available online: https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/NM (accessed on 9 May 2024).

- United States Census Bureau. Race and Ethnicity in the United States: 2010 Census and 2020 Census. 2021. Available online: https://www.census.gov/library/visualizations/interactive/race-and-ethnicity-in-the-united-state-2010-and-2020-census.html (accessed on 9 May 2024).

| Variable | Group | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cohort | Adolescent | 278 | 25.48 |

| Adult | 813 | 74.52 | |

| Race | American Indian/Alaska Native | 99 | 9.07 |

| Asian | 5 | 0.46 | |

| Black/African American | 91 | 8.34 | |

| Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander | 1 | 0.09 | |

| White | 810 | 74.24 | |

| More than one | 21 | 1.92 | |

| Unknown/Not reported | 64 | 5.87 | |

| Ethnicity | Hispanic/Latino | 681 | 62.42 |

| Not Hispanic/Latino | 406 | 37.21 | |

| Unknown/Not reported | 4 | 0.37 |

| Adolescents (n = 278) | Adults (n = 813) | Group Differences | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Mean | Std. Dev. | Mean | Std. Dev. | T | df | p-Value |

| PCL Total | 23.48 | 6.07 | 20.60 | 6.75 | 6.29 | 1089 | <0.001 |

| PCL Factor 1 | 6.65 | 3.07 | 5.69 | 3.35 | 4.22 | 1089 | <0.001 |

| PCL Factor 2 | 14.57 | 3.24 | 12.70 | 3.72 | 7.49 | 1089 | <0.001 |

| PCL Facet 1 | 2.19 | 1.85 | 2.04 | 1.92 | 1.15 | 1089 | 0.252 |

| PCL Facet 2 | 4.46 | 1.79 | 3.65 | 2.02 | 5.90 | 1089 | <0.001 |

| PCL Facet 3 | 6.30 | 2.01 | 5.52 | 2.15 | 5.31 | 1088 | <0.001 |

| PCL Facet 4 | 8.29 | 1.65 | 7.20 | 2.26 | 7.35 | 1071 | <0.001 |

| χ2 | df | RMSEA (90% CI) | CFI | SRMR | TLI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total sample | 311.603 | 87 | 0.049 (0.043–0.055) | 0.965 | 0.036 | 0.938 |

| Adolescent | 126.747 | 87 | 0.041 (0.024–0.055) | 0.976 | 0.054 | 0.958 |

| Adult | 264.404 | 87 | 0.050 (0.043–0.057) | 0.961 | 0.039 | 0.931 |

| χ2 | df | RMSEA (90% CI) | ΔRMSEA | CFI | ΔCFI | SRMR | ΔSRMR | TLI | ΔTLI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Configural | 371.450 | 174 | 0.046 (0.039–0.052) | 0.967 | 0.043 | 0.942 | ||||

| Scalar | 562.502 | 244 | 0.049 (0.044–0.054) | 0.003 | 0.947 | 0.020 | 0.059 | 0.016 | 0.934 | 0.008 |

| Scalar * | 526.172 | 242 | 0.046 (0.041–0.052) | 0.000 | 0.953 | 0.014 | 0.059 | 0.016 | 0.940 | 0.002 |

| PCL:YV Items | INT | AFF | LIF | ANT |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interpersonal | ||||

| 1 | 0.65 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.01 |

| 2 | 0.82 | 0.18 | −0.05 | 0.04 |

| 4 | 0.57 | 0.03 | 0.69 | −0.16 |

| 5 | 0.41 | −0.06 | 0.45 | 0.06 |

| Affective | ||||

| 6 | 0.01 | 0.65 | 0.01 | 0.25 |

| 7 | 0.15 | 0.47 | 0.21 | 0.05 |

| 8 | 0.04 | 0.42 | 0.02 | 0.47 |

| 16 | 0.30 | 0.28 | 0.01 | −0.05 |

| Lifestyle | ||||

| 3 | 0.21 | −0.05 | 0.46 | 0.16 |

| 9 | 0.15 | 0.00 | 0.61 | 0.02 |

| 13 | 0.06 | 0.30 | 0.38 | −0.06 |

| 14 | −0.13 | 0.01 | 0.45 | 0.15 |

| 15 | −0.13 | 0.04 | 0.71 | 0.00 |

| Antisocial | ||||

| 10 | 0.02 | 0.14 | −0.06 | 0.58 |

| 12 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.53 |

| 18 | −0.14 | −0.02 | 0.07 | 0.79 |

| 19 | −0.16 | 0.04 | 0.35 | 0.13 |

| 20 | 0.05 | −0.28 | 0.71 | 0.45 |

| PCL-R Items | INT | AFF | LIF | ANT |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interpersonal | ||||

| 1 | 0.86 | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.02 |

| 2 | 0.66 | 0.21 | −0.04 | 0.06 |

| 4 | 0.45 | 0.04 | 0.50 | −0.22 |

| 5 | 0.39 | −0.08 | 0.38 | 0.10 |

| Affective | ||||

| 6 | 0.01 | 0.69 | 0.00 | 0.31 |

| 7 | 0.10 | 0.44 | 0.12 | 0.05 |

| 8 | 0.03 | 0.49 | 0.02 | 0.64 |

| 16 | 0.26 | 0.35 | 0.00 | −0.07 |

| Lifestyle | ||||

| 3 | 0.18 | −0.07 | 0.35 | 0.23 |

| 9 | 0.13 | −0.01 | 0.46 | 0.04 |

| 13 | 0.05 | 0.38 | 0.30 | −0.09 |

| 14 | −0.15 | 0.02 | 0.46 | 0.30 |

| 15 | −0.13 | 0.05 | 0.63 | 0.00 |

| Antisocial | ||||

| 10 | 0.01 | 0.13 | −0.03 | 0.63 |

| 12 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.66 |

| 18 | −0.08 | −0.02 | 0.03 | 0.75 |

| 19 | −0.20 | 0.08 | 0.40 | 0.29 |

| 20 | 0.04 | −0.29 | 0.45 | 0.55 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ngo, D.A.; Neumann, C.S.; Maurer, J.M.; Harenski, C.; Kiehl, K.A. Psychopathic Traits in Adult versus Adolescent Males: Measurement Invariance across the PCL-R and PCL:YV. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 672. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14080672

Ngo DA, Neumann CS, Maurer JM, Harenski C, Kiehl KA. Psychopathic Traits in Adult versus Adolescent Males: Measurement Invariance across the PCL-R and PCL:YV. Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 14(8):672. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14080672

Chicago/Turabian StyleNgo, Darlene A., Craig S. Neumann, J. Michael Maurer, Carla Harenski, and Kent A. Kiehl. 2024. "Psychopathic Traits in Adult versus Adolescent Males: Measurement Invariance across the PCL-R and PCL:YV" Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 8: 672. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14080672

APA StyleNgo, D. A., Neumann, C. S., Maurer, J. M., Harenski, C., & Kiehl, K. A. (2024). Psychopathic Traits in Adult versus Adolescent Males: Measurement Invariance across the PCL-R and PCL:YV. Behavioral Sciences, 14(8), 672. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14080672