Are Children Following High Trajectories of Disruptive Behaviors in Early Childhood More or Less Likely to Follow Concurrent High Trajectories of Internalizing Problems?

Abstract

1. Introduction

The Present Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Joint Trajectories of DBs

2.2.2. Internalizing Problems

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

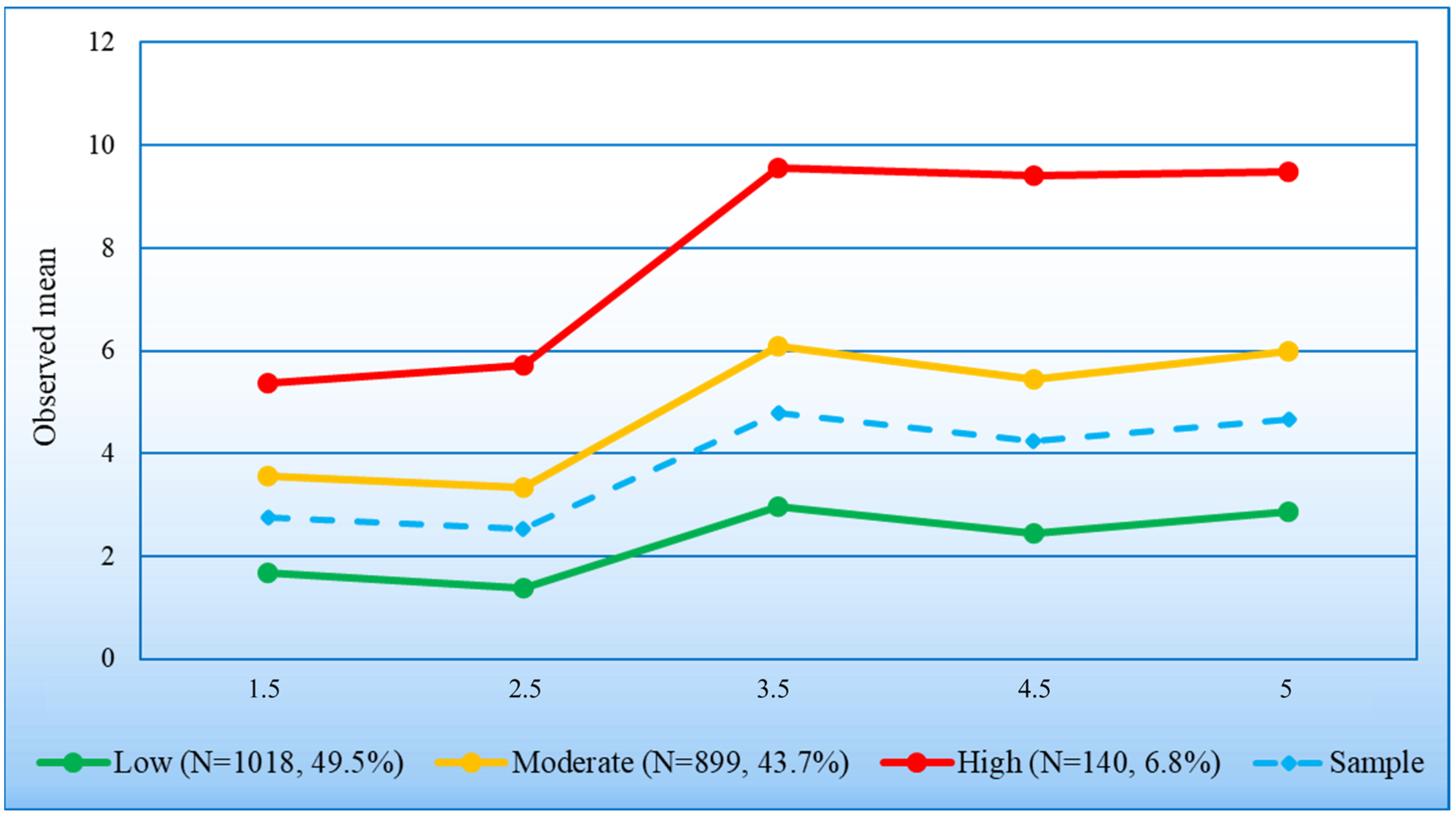

3.1. Longitudinal Growth Curve Model and Trajectory Classes of Internalizing

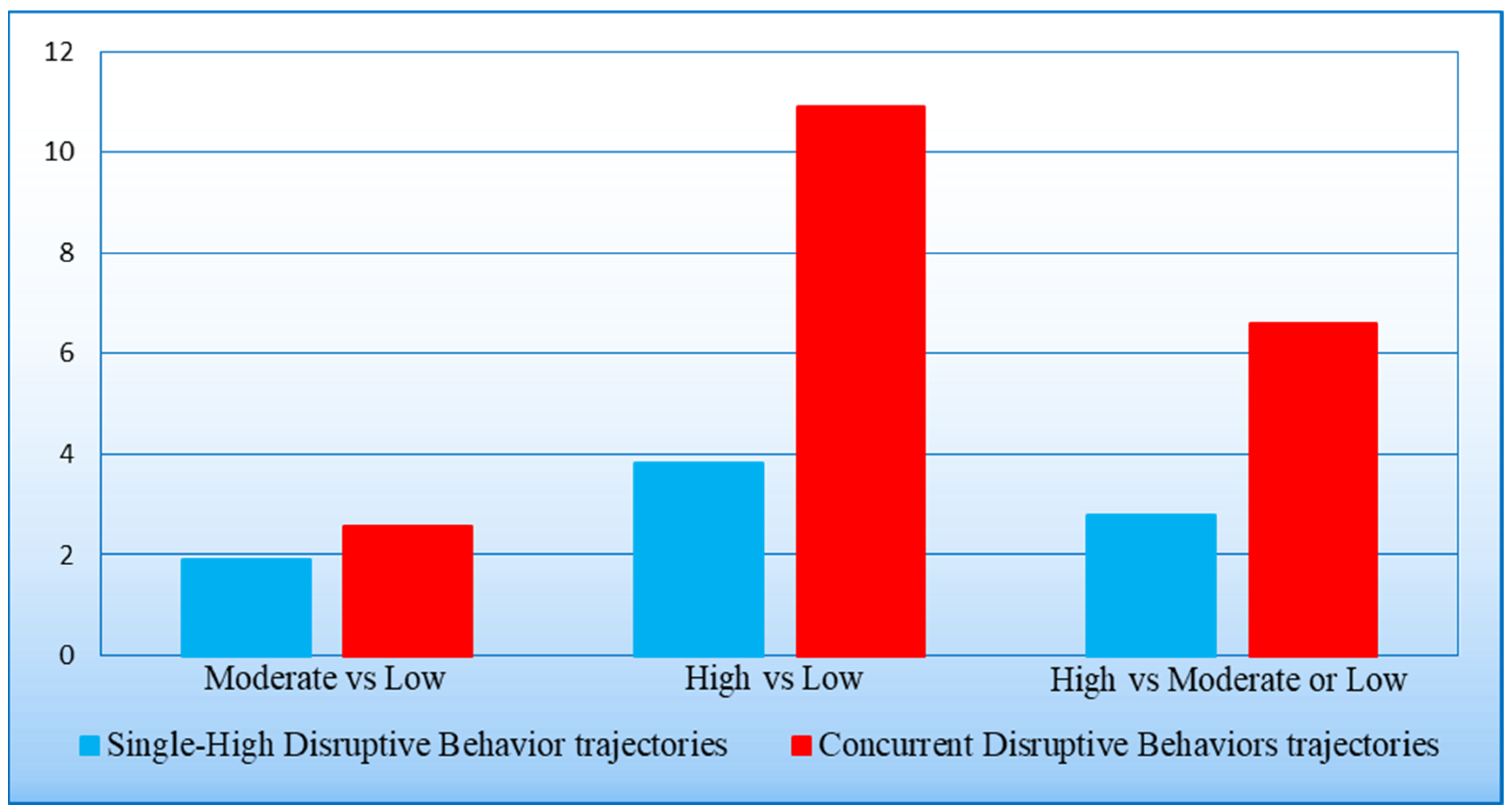

3.2. Associations between Trajectory Classes of DBs and Trajectory Classes of Internalizing Problems

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Muthén, B.; Muthén, L.K. Integrating Person-Centered and Variable-Centered analyses: Growth mixture modeling with latent trajectory classes. Alcohol./Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2000, 24, 882–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagin, D.S. Group-Based Modeling of Development; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Carbonneau, R.; Boivin, M.; Brendgen, M.; Nagin, D.S.; Tremblay, R.E. Comorbid Development of Disruptive Behaviors from age 1½ to 5 Years in a Population Birth-Cohort and Association with School Adjustment in First Grade. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2016, 44, 677–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Côté, S.; Vaillancourt, T.; LeBlanc, J.C.; Nagin, D.S.; Tremblay, R.E. The Development of Physical Aggression from Toddlerhood to Pre-Adolescence: A Nation Wide Longitudinal Study of Canadian Children. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2006, 34, 68–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galéra, C.; Côté, S.M.; Bouvard, M.P.; Pingault, J.-B.; Melchior, M.; Michel, G.; Boivin, M.; Tremblay, R.E. Early risk factors for Hyperactivity-Impulsivity and inattention trajectories from age 17 months to 8 years. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2011, 68, 1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutman, L.M.; Joshi, H.; Schoon, I. Developmental Trajectories of Conduct Problems and Cumulative Risk from Early Childhood to Adolescence. J. Youth Adolesc. 2019, 48, 181–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miner, J.L.; Clarke-Stewart, K.A. Trajectories of externalizing behavior from age 2 to age 9: Relations with gender, temperament, ethnicity, parenting, and rater. Dev. Psychol. 2008, 44, 771–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NICHD Early Child Care Research Network. Trajectories of Physical Aggression from Toddlerhood to Middle School: Predictors, correlates, and outcomes. Monogr. Soc. Res. Child Dev. 2004, 69, 1–129. [Google Scholar]

- Petitclerc, A.; Boivin, M.; Dionne, G.; Zoccolillo, M.; Tremblay, R.E. Disregard for rules: The early development and predictors of a specific dimension of disruptive behavior disorders. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry Allied Discip. 2009, 50, 1477–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pingault, J.; Tremblay, R.E.; Vitaro, F.; Carbonneau, R.; Génolini, C.; Falissard, B.; Côté, S. Childhood Trajectories of Inattention and Hyperactivity and Prediction of Educational Attainment in Early Adulthood: A 16-Year Longitudinal Population-Based Study. Am. J. Psychiatry 2011, 168, 1164–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, D.S.; Lacourse, É.; Nagin, D.S. Developmental trajectories of conduct problems and hyperactivity from ages 2 to 10. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry Allied Discip. 2005, 46, 931–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teymoori, A.; Côté, S.; Jones, B.; Nagin, D.S.; Boivin, M.; Vitaro, F.; Orri, M.; Tremblay, R.E. Risk factors associated with boys’ and girls’ developmental trajectories of physical aggression from early childhood through early adolescence. JAMA Netw. Open 2018, 1, e186364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tremblay, R.E.; Nagin, D.S.; Séguin, J.R.; Zoccolillo, M.; Zelazo, P.D.; Boivin, M.; Pérusse, D.; Japel, C. Physical aggression during Early Childhood: Trajectories and predictors. Pediatrics 2004, 114, e43–e50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finsaas, M.C.; Bufferd, S.J.; Dougherty, L.R.; Carlson, G.A.; Klein, D.N. Preschool psychiatric disorders: Homotypic and heterotypic continuity through middle childhood and early adolescence. Psychol. Med. 2018, 48, 2159–2168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lévy, F.; Hawes, D.J.; Johns, A. Externalizing and internalizing comorbidity. In The Oxford Handbook of Externalizing Spectrum Disorders; Beauchaine, T.P., Hinshaw, S.P., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016; pp. 443–460. [Google Scholar]

- Lahey, B.B.; Moore, T.M.; Kaczkurkin, A.N.; Zald, D.J. Hierarchical models of psychopathology: Empirical support, implications, and remaining issues. World Psychiatry 2021, 20, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forbes, M.K.; Tackett, J.L.; Markon, K.E.; Krueger, R.F. Beyond comorbidity: Toward a dimensional and hierarchical approach to understanding psychopathology across the life span. Dev. Psychopathol. 2016, 28 Pt 1, 971–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tully, E.C.; Iacono, W.G. An integrative common liabilities model for the comorbidity of substance use disorders with externalizing and internalizing disorders. In The Oxford Handbook of Substance Use and Substance Use Disorders; Sher, K.J., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016; pp. 187–212. [Google Scholar]

- Rhee, S.H.; Lahey, B.B.; Waldman, I.D. Comorbidity among Dimensions of Childhood Psychopathology: Converging Evidence from Behavior Genetics. Child Dev. Perspect. 2014, 9, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bubier, J.L.; Drabick, D.A. Co-occurring anxiety and disruptive behavior disorders: The roles of anxious symptoms, reactive aggression, and shared risk processes. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2009, 29, 658–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilliom, M.; Shaw, D.S. Codevelopment of externalizing and internalizing problems in early childhood. Dev. Psychopathol. 2004, 16, 313–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moilanen, K.L.; Shaw, D.S.; Maxwell, K.L. Developmental cascades: Externalizing, internalizing, and academic competence from middle childhood to early adolescence. Dev. Psychopathol. 2010, 22, 635–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papachristou, E.; Flouri, E. The codevelopment of internalizing symptoms, externalizing symptoms, and cognitive ability across childhood and adolescence. Dev. Psychopathol. 2019, 32, 1375–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbonneau, R.; Vitaro, F.; Brendgen, M.; Boivin, M.; Tremblay, R.E. Internalizing problems associated with developmental patterns of single and co-occurrent externalizing behaviors over the preschool years. Dev. Psychol. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drabick, D.G.; Ollendick, T.H.; Bubier, J.L. Co-occurrence of ODD and anxiety: Shared risk processes and evidence for a dual-pathway model. Clin. Psychol. 2010, 17, 307–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isdahl-Troye, A.; Villar, P.; Domínguez-Álvarez, B.; Romero, E.; Deater-Deckard, K. The Development of Co-Occurrent Anxiety and Externalizing Problems from Early Childhood: A Latent Transition Analysis Approach. Res. Child Adolesc. Psychopathol. 2021, 50, 505–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahendran, N.; Aitken, M.; Andrade, B.F. Comorbid Internalizing Symptoms in Children with Disruptive Behavior Disorders: Buffering Effects or Multiple Problem Effects? J. Child Fam. Stud. 2021, 30, 474–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Øvergaard, K.R.; Aase, H.; Torgersen, S.; Reichborn-Kjennerud, T.; Oerbeck, B.; Myhre, A.M.; Zeiner, P. Continuity in features of anxiety and attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder in young preschool children. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2014, 23, 743–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wichström, L.; Berg-Nielsen, T.S.; Angold, A.; Egger, H.L.; Solheim, E.; Sveen, T.H. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders in preschoolers. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry Allied Discip. 2012, 53, 695–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ezpeleta, L.; Granero, R.; De La Osa, N.; Penelo, E.; Domènech, J. Dimensions of oppositional defiant disorder in 3-year-old preschoolers. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry Allied Discip. 2012, 53, 1128–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halldorsdottir, T.; Fraire, M.G.; Drabick, D.a.G.; Ollendick, T.H. Co-Occurring Conduct Problems and Anxiety: Implications for the Functioning and Treatment of Youth with Oppositional Defiant Disorder. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 3405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fanti, K.A.; Henrich, C.C. Trajectories of pure and co-occurring internalizing and externalizing problems from age 2 to age 12: Findings from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Study of Early Child Care. Dev. Psychol. 2010, 46, 1159–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BīLgīÇ, A.; Türkoğlu, S.; Özcan, Ö.; Tufan, A.E.; Savaş, Y.; Yüksel, T. Relationship between anxiety, anxiety sensitivity and conduct disorder symptoms in children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2013, 22, 523–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haines, N.; Beauchaine, T.P.; Galdo, M.; Rogers, A.H.; Hahn, H.; Pitt, M.A.; Myung, J.I.; Turner, B.M.; Ahn, W.-Y. Anxiety modulates preference for immediate rewards among trait-impulsive individuals: A hierarchical Bayesian analysis. Clin. Psychol. Sci. 2020, 8, 1017–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotelnikova, Y.; Mackrell, S.V.M.; Clark, L.A.; Hayden, E.P. A longitudinal, multimethod study of children’s early emerging maladaptive personality traits: Stress sensitivity as a protective factor. J. Res. Personal. 2024, 109, 104448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbonneau, R.; Vitaro, F.; Brendgen, M.; Tremblay, R.E. Alcohol, Marijuana and Other Illicit Drugs Use Throughout Adolescence: Co-occurring Courses and Preadolescent Risk-Factors. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2022, 53, 1194–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colder, C.R.; Scalco, M.; Trucco, E.M.; Read, J.P.; Lengua, L.J.; Wieczorek, W.F.; Hawk, L.W., Jr. Prospective associations of internalizing and externalizing problems and their co-occurrence with early adolescent substance use. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2013, 41, 667–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polier, G.G.; Herpertz-Dahlmann, B.; Matthias, K.; Konrad, K.; Vloet, T.D. Associations between trait anxiety and psychopathological characteristics of children at high risk for severe antisocial development. Adhd Atten. Deficit Hyperact. Disord. 2010, 2, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mesman, J.; Bongers, I.L.; Koot, H.M. Preschool Developmental Pathways to preadolescent internalizing and externalizing problems. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry Allied Discip. 2001, 42, 679–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín, V.; Granero, R.; Ezpeleta, L. Comorbidity of oppositional defiant disorder and anxiety disorders in preschoolers. Psicothema 2014, 26, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Angold, A.; Costello, E.J.; Erkanli, A. Comorbidity. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 1999, 40, 57–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carbonneau, R.; Tremblay, R.E. Antisocial Behavior Prevention: Toward a developmental biopsychosocial perspective. In Clinical Forensic Psychology: Introductory Perspectives on Offending; Garofalo, C., Sijtsema, J.J., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2022; pp. 29–47. [Google Scholar]

- Tremblay, R.E.; Vitaro, F.; Côté, S. Developmental Origins of Chronic Physical Aggression: A Bio-Psycho-Social model for the next generation of Preventive Interventions. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2018, 69, 383–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bufferd, S.J.; Dougherty, L.R.; Carlson, G.A.; Klein, D.N. Parent-reported mental health in preschoolers: Findings using a diagnostic interview. Compr. Psychiatry 2011, 52, 359–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tandon, M.; Cardeli, E.; Luby, J. Internalizing disorders in early childhood: A review of depressive and anxiety disorders. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 2009, 18, 593–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Erlbaum: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Sawilowsky, S.S. New effect size rules of thumb. J. Mod. Appl. Stat. Methods 2009, 8, 597–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simms, U.; Watson, D. The construct validation approach to personality scale construction. In Handbook of Research Methods in Personality Psychology; Robins, R.W., Frayley, R.C., Kruger, R.F., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 240–258. [Google Scholar]

- Raykov, T. Estimation of composite reliability for congeneric measures. Appl. Psychol. Meas. 1997, 21, 173–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error: Algebra and Statistics. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthén, L.K.; Muthén, B.O. Mplus User’s Guide, 8th ed.; Muthén & Muthén: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1998–2017. [Google Scholar]

- Behar, L.; Stringfield, S. A behavior rating scale for the preschool child. Dev. Psychol. 1974, 10, 601–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achenbach, T.M. Child Behavior Checklist; Department of Psychiatry, University of Vermont: Burlington, VT, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Battaglia, M.; Touchette, É.; Garon-Carrier, G.; Dionne, G.; Côté, S.M.; Vitaro, F.; Tremblay, R.E.; Boivin, M. Distinct trajectories of separation anxiety in the preschool years: Persistence at school entry and early-life associated factors. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2016, 57, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Côté, S.; Boivin, M.; Liu, X.; Nagin, D.S.; Zoccolillo, M.; Tremblay, R.E. Depression and anxiety symptoms: Onset, developmental course and risk factors during early childhood. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry Allied Discip. 2009, 50, 1201–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zdebik, M.A.; Boivin, M.; Battaglia, M.; Tremblay, R.E.; Falissard, B.; Côté, S. Childhood multi-trajectories of shyness, anxiety and depression: Associations with adolescent internalizing problems. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2019, 64, 101050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, S.L.; Muthen, B. Relating Latent Class Analysis Results to Variables Not Included in the Analysis. 2009. Available online: http://www.statmodel.com/download/Relatinglca.pdf (accessed on 28 June 2024).

- Wickrama, K.S.; Lee, T.K.; O’Neal, C.W.; Lorenz, F.O. Higher-Order Growth Curves and Mixture Modeling with Mplus; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Nylund-Gibson, K.; Choi, A.Y. Ten frequently asked questions about latent class analysis. Transl. Issues Psychol. Sci. 2018, 4, 440–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardin, J.W.; Hilbe, J.M. Generalized Linear Models and Extensions, 4th ed.; Stata Press: College Station, TX, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Dziak, J.J.; Coffman, D.L.; Lanza, S.T.; Li, R.; Jermiin, L.S. Sensitivity and specificity of information criteria. Brief. Bioinform. 2020, 21, 553–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnham, K.P.; Anderson, D.R. Model Selection and Multimodel Inference, 2nd ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kostyrka-Allchorne, K.; Wass, S.V.; Sonuga-Barke, E.J.S. Research Review: Do parent ratings of infant negative emotionality and self-regulation predict psychopathology in childhood and adolescence? A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective longitudinal studies. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2020, 61, 401–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lilienfeld, S.O. Comorbidity between and within childhood externalizing and internalizing disorders: Reflections and directions. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2003, 31, 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beauchaine, T.P.; Tackett, J.L. Irritability as a Transdiagnostic Vulnerability Trait: Current Issues and Future Directions. Behav. Ther. 2020, 51, 350–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finlay-Jones, A.L.; Ang, J.E.; Brook, J.; Lucas, J.D.; MacNeill, L.A.; Mancini, V.O.; Kottampally, K.; Elliott, C.; Smith, J.D.; Wakschlag, L.S. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis: Early Irritability as a Transdiagnostic Neurodevelopmental Vulnerability to Later Mental Health Problems. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2024, 63, 184–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aldao, A.; Gee, D.G.; De Los Reyes, A.; Seager, I. Emotion regulation as a transdiagnostic factor in the development of internalizing and externalizing psychopathology: Current and future directions. Dev. Psychopathol. 2016, 28 Pt 1, 927–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraire, M.G.; Ollendick, T.H. Anxiety and Oppositional Defiant Disorder: A Transdiagnostic Conceptualization. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2013, 33, 229–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santens, E.; Claes, L.; Dierckx, E.; Dom, G. Effortful control—A transdiagnostic dimension underlying internalizing and externalizing psychopathology. Neuropsychobiology 2020, 79, 255–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shields, A.N.; Reardon, K.W.; Brandes, C.M.; Tackett, J.L. The p factor in children: Relationships with executive functions and effortful control. J. Res. Pers. 2019, 82, 103853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendler, K.S.; Neale, M.C. Endophenotype: A conceptual analysis. Mol. Psychiatry 2010, 15, 789–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atherton, O.E.; Lawson, K.M.; Ferrer, E.; Robins, R.W. The role of effortful control in the development of ADHD, ODD, and CD symptoms. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2020, 118, 1226–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latimer, K.; Wilson, P.; Kemp, J.; Thompson, L.; Sim, F.; Gillberg, C.; Puckering, C.; Minnis, H. Disruptive behaviour disorders: A systematic review of environmental antenatal and early years risk factors. Child Care Health Dev. 2012, 38, 611–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, X.; Burke, M.D.; Ramirez, G.; Xu, Z.; Bowman-Perrott, L. A Meta-Analysis of Social Skills Interventions for Preschoolers with or at Risk of Early Emotional and Behavioral Problems. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martel, M.M. Sexual selection and sex differences in the prevalence of childhood externalizing and adolescent internalizing disorders. Psychol. Bull. 2013, 139, 1221–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rothenberg, W.A.; Lansford, J.E.; Chang, L.; Deater-Deckard, K.; Di Giunta, L.; Dodge, K.A.; Malone, P.S.; Oburu, P.; Pastorelli, C.; Skinner, A.T.; et al. Examining the internalizing pathway to substance use frequency in 10 cultural groups. Addict. Behav. 2020, 102, 106214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carter, A.S.; Briggs-Gowan, M.J.; Davis, N. Assessment of young children’s social-emotional development and psychopathology: Recent advances and recommendations for practice. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2004, 45, 109–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biedzio, D.; Wakschlag, L.S. Developmental emergence of disruptive behaviors beginning in infancy: Delineating normal-abnormal boundaries to enhance early identification. In Handbook of Infant Mental Health, 4th ed.; Zeenah, C., Ed.; Chapter 24; Guilford: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Petersen, K.; Qualter, P.; Humphrey, N. The Application of Latent Class Analysis for Investigating Population Child Mental Health: A Systematic review. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achenbach, T.M.; Ivanova, M.Y.; Rescorla, L.A.; Turner, L.V.; Althoff, R.R. Internalizing-externalizing problems: Review and recommendations for clinical and research applications. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2016, 55, 647–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Model | LCGA | LCGMM | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Distribution | Normal | Censored Normal | Censored Normal | ||

| Fit Indicators | Three classes | Four classes | Three classes | Four classes | 3-classes |

| AIC | 44,193.09 | 43,993.98 | 43,535.35 | 43,415.23 | 43,547.35 |

| BIC | 44,283.15 | 44,106.56 | 43,625.41 | 43,527.81 | 43,671.19 |

| SSA-BIC | 44,232.32 | 44,043.02 | 43,574.58 | 43,464.26 | 43,601.29 |

| VLMR-LRT (p) | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.034 | 0.003 | 0.035 |

| LMR-ALRT (p) | 0.004 | 0.003 | 0.037 | 0.003 | 0.036 |

| Entropy | 0.74 | 0.74 | 0.72 | 0.66 | 0.70 |

| DB Trajectory Classes (n) | Trajectory Classes of Internalizing Problems | Moderate vs. Low | High vs. Low | High vs. Low or Moderate | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low (1019) | Moderate (899) | High (139) | Sig. | OR | OR 95% CI | Sig. | OR | OR 95% CI | Sig. | OR | OR 95% CI | |

| DB reference class 1 (1479) | 56.0 | 40.4 | 3.7 | |||||||||

| HIonly (67) | 34.3 | 56.7 | 9.0 | 0.002 | 2.29 | 1.35–3.89 | 0.004 | 4.00 | 1.56–10.24 | 0.034 | 2.60 | 1.08–6.27 |

| NConly (93) | 36.6 | 50.5 | 12.9 | 0.005 | 1.92 | 1.22–3.02 | <0.001 | 5.41 | 2.65–11.05 | <0.001 | 3.91 | 2.01–7.60 |

| PAonly (123) | 41.5 | 51.2 | 7.3 | 0.006 | 1.71 | 1.17–2.52 | 0.010 | 2.71 | 1.27–5.79 | 0.049 | 2.08 | 1.03–4.33 |

| HI+NC (97) | 21.6 | 57.7 | 20.6 | <0.001 | 3.70 | 2.22–6.17 | <0.001 | 14.60 | 7.46–28.58 | <0.001 | 6.85 | 3.91–12.02 |

| NC+PA (57) | 35.1 | 52.6 | 12.3 | 0.013 | 2.08 | 1.17–3.70 | <0.001 | 5.37 | 2.17–13.25 | 0.002 | 3.69 | 1.60–8.53 |

| HI+NC+PA (141) | 29.8 | 47.5 | 22.7 | <0.001 | 2.21 | 1.48–3.30 | <0.001 | 11.6 | 6.84–19.97 | <0.001 | 7.75 | 4.80–12.50 |

| Sample (2057) | 49.5 | 43.7 | 6.8 | |||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Carbonneau, R.; Vitaro, F.; Brendgen, M.; Boivin, M.; Tremblay, R.E. Are Children Following High Trajectories of Disruptive Behaviors in Early Childhood More or Less Likely to Follow Concurrent High Trajectories of Internalizing Problems? Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 571. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14070571

Carbonneau R, Vitaro F, Brendgen M, Boivin M, Tremblay RE. Are Children Following High Trajectories of Disruptive Behaviors in Early Childhood More or Less Likely to Follow Concurrent High Trajectories of Internalizing Problems? Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 14(7):571. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14070571

Chicago/Turabian StyleCarbonneau, Rene, Frank Vitaro, Mara Brendgen, Michel Boivin, and Richard E. Tremblay. 2024. "Are Children Following High Trajectories of Disruptive Behaviors in Early Childhood More or Less Likely to Follow Concurrent High Trajectories of Internalizing Problems?" Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 7: 571. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14070571

APA StyleCarbonneau, R., Vitaro, F., Brendgen, M., Boivin, M., & Tremblay, R. E. (2024). Are Children Following High Trajectories of Disruptive Behaviors in Early Childhood More or Less Likely to Follow Concurrent High Trajectories of Internalizing Problems? Behavioral Sciences, 14(7), 571. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14070571