From Struggle to Strength: Coping with Abusive Supervision in Project Teams through Proactive Behavior and Team Building

Abstract

1. Introduction

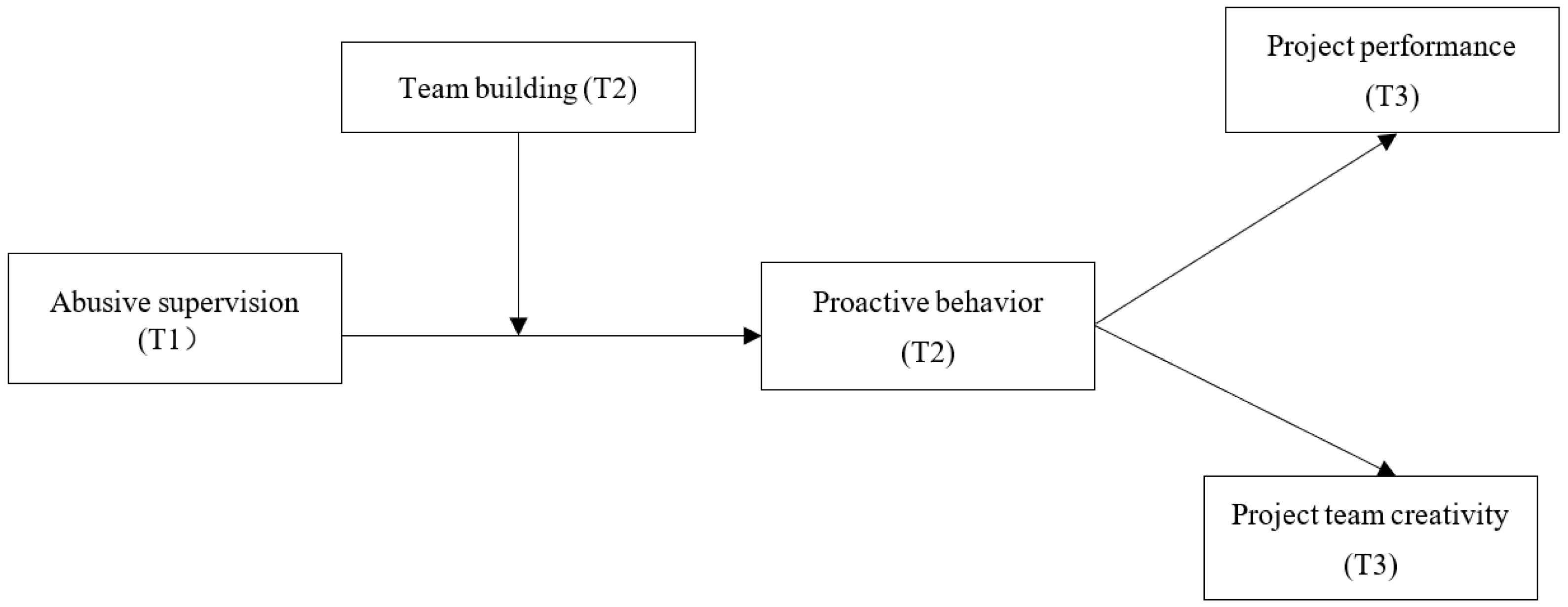

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses

2.1. Proactive Motivation Theory

2.2. Abusive Supervision, Project Performance, and Project Team Creativity

2.3. Mediating Effect of Proactive Behavior in Teams

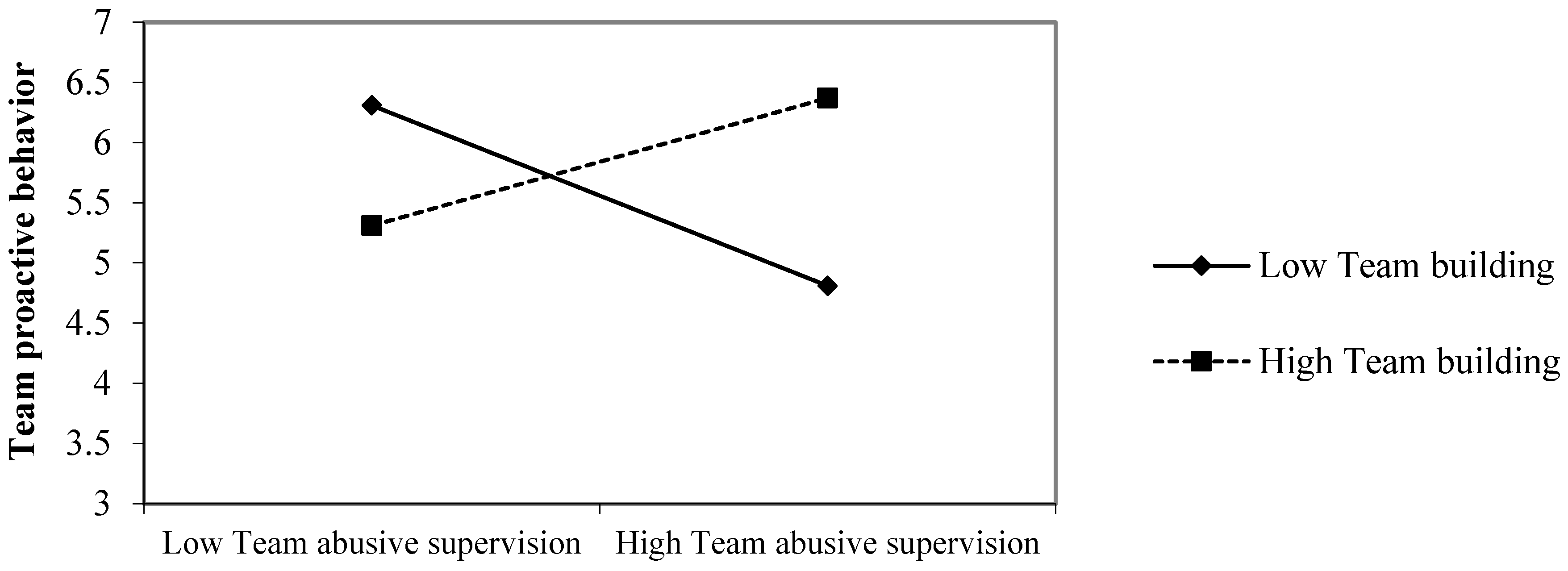

2.4. Moderating Effect of Team Building

3. Method

3.1. Participants and Procedures

3.2. Measures

3.3. Data Analysis Technique

4. Results

4.1. Aggregating Data to the Team Level

4.2. Preliminary Analysis

4.3. Correlation Analysis

4.4. Tests of Hypotheses

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Limitations and Directions for Future Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Müller, R.; Turner, R. The Influence of Project Managers on Project Success Criteria and Project Success by Type of Project. Eur. Manag. J. 2007, 25, 298–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampaio, S.; Wu, Q.; Cormican, K.; Varajão, J. Reach for the Sky: Analysis of Behavioral Competencies Linked to Project Success. Int. J. Manag. Proj. Bus. 2022, 15, 192–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aga, D.A.; Noorderhaven, N.; Vallejo, B. Transformational Leadership and Project Success: The Mediating Role of Team-Building. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2016, 34, 806–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nauman, S.; Musawir, A.U.; Munir, H.; Rasheed, I. Enhancing the Impact of Transformational Leadership and Team-Building on Project Success: The Moderating Role of Empowerment Climate. Int. J. Manag. Proj. Bus. 2022, 15, 423–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, C. Linking Frontline Construction Workers’ Perceived Abusive Supervision to Work Engagement: Job Insecurity as the Game-Changing Mediation and Job Alternative as a Moderator. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2023. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nauman, S.; Bhatti, S.H.; Imam, H.; Khan, M.S. How Servant Leadership Drives Project Team Performance Through Collaborative Culture and Knowledge Sharing. Proj. Manag. J. 2022, 53, 17–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, E.C.; Mazur, A.K.; Ashkanasy, N.M. Rallying the Troops or Beating the Horses? How Project-Related Demands Can Lead to Either High-Performance or Abusive Supervision. Proj. Manag. J. 2015, 46, 10–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tepper, B.J. Consequences of Abusive Supervision. Acad. Manag. J. 2000, 432, 178–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tepper, B.J. Abusive Supervision in Work Organizations: Review, Synthesis, and Research Agenda. J. Manag. 2007, 33, 261–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, T.; Tian, A.W.; Lee, A.; Hughes, D.J. Abusive Supervision: A Systematic Review and Fundamental Rethink. Leadersh. Q. 2021, 32, 101540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogunfowora, B.; Weinhardt, J.M.; Hwang, C.C. Abusive Supervision Differentiation and Employee Outcomes: The Roles of Envy, Resentment, and Insecure Group Attachment. J. Manag. 2021, 47, 623–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wei, Y.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, X.; Peng, Y. Abusive Supervision and Creativity: Investigating the Moderating Role of Performance Improvement Attribution and the Mediating Role of Psychological Availability. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 658743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, C.; Yang, J. Abusive Supervision and Employee Creativity: The Mediating Role of Passion for Inventing and the Moderating Role of Financial Incentives and Innovative Culture. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 42, 29815–29830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, L. Abusive Supervision and Work Performance: The Moderating Role of Abusive Supervision Variability. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 2016, 44, 1089–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.-R.; Kang, S.-W.; Choi, S.B. Abusive Supervision and Employee’s Creative Performance: A Serial Mediation Model of Relational Conflict and Employee Silence. Behav. Sci. 2022, 12, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hmieleski, K.M.; Cole, M.S. The Contingent Effects of Intrateam Abusive Behavior on Team Thriving and New Venture Performance. J. Manag. 2023, 49, 808–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhou, M.; Zhu, H.; Wu, X. The Impact of Abusive Supervision Differentiation on Team Performance in Team Competitive Climates. Pers. Rev. 2023, 52, 901–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Nie, Q.; Cheng, Y. Team Abusive Supervision and Team Behavioral Resistance to Change: The Roles of Distrust in the Supervisor and Perceived Frequency of Change. J. Organ. Behav. 2023, 44, 1016–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerzner, H.A. Project Management: A Systems Approach to Planning, Scheduling, and Controlling, 11th ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2013; ISBN 978-1-118-02227-6. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, F.; Wang, L.; Yu, M.; Müller, R.; Sun, X. Transformational Leadership and Project Team Members’ Silence: The Mediating Role of Feeling Trusted. Int. J. Manag. Proj. Bus. 2019, 12, 845–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meredith, J.R.; Shafer, S.M.; Mantel, S.J., Jr. Project Management: A Managerial Approach, 11th ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2021; ISBN 978-1-119-80383-6. [Google Scholar]

- Men, C.; Yue, L.; Weiwei, H.; Liu, B.; Li, G. How Abusive Supervision Climate Affects Team Creativity: The Contingent Role of Task Interdependence. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2022, 25, 1183–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priesemuth, M.; Schminke, M.; Ambrose, M.L.; Folger, R. Abusive Supervision Climate: A Multiple-Mediation Model of Its Impact on Group Outcomes. Acad. Manag. J. 2014, 57, 1513–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anantatmula, V.S. Project Manager Leadership Role in Improving Project Performance. Eng. Manag. J. 2010, 22, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X. The Effect of Relationship Management on Project Performance in Construction. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2012, 30, 188–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.-H. Understanding the Benefits and Detriments of Conflict on Team Creativity Process. Creat. Innov. Manag. 2006, 15, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- To, M.L.; Fisher, C.D.; Ashkanasy, N.M.; Zhou, J. Feeling Differently, Creating Together: Affect Heterogeneity and Creativity in Project Teams. J. Organ. Behav. 2021, 42, 1228–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Zhang, G.; Chan, A. Abusive Supervision and Subordinate Proactive Behavior: Joint Moderating Roles of Organizational Identification and Positive Affectivity. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 157, 829–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Ma, E.; Lin, X. Can Proactivity Translate to Creativity? Examinations at Individual and Team Levels. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 98, 103034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, K.; Lam, W.; Wang, W. Roles of Gender and Identification on Abusive Supervision and Proactive Behavior. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2015, 32, 671–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farh, C.I.C.; Chen, Z. Beyond the Individual Victim: Multilevel Consequences of Abusive Supervision in Teams. J. Appl. Psychol. 2014, 99, 1074–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parker, S.K.; Bindl, U.K.; Strauss, K. Making Things Happen: A Model of Proactive Motivation. J. Manag. 2010, 36, 827–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do Nascimento, T.T.; Porto, J.B.; Kwantes, C.T. Transformational Leadership and Follower Proactivity in a Volunteer Workforce. Nonprofit Manag. Leadersh. 2018, 28, 565–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Inness, M. Transformational Leadership and Employee Voice: A Model of Proactive Motivation. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2019, 40, 777–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, A.J.; Loi, R.; Chow, C.W.C. Why and When Proactive Employees Take Charge at Work: The Role of Servant Leadership and Prosocial Motivation. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2022, 31, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Hsu, C.; Wang, T.; Lowry, P.B. The Antecedents of Employees’ Proactive Information Security Behaviour: The Perspective of Proactive Motivation. Inf. Syst. J. 2023. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkman, B.L.; Rosen, B. Beyond Self-Management: Antecedents and Consequences of Team Empowerment. Acad. Manag. J. 1999, 42, 58–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhao, C.; Yang, Z.; Gao, Z. The Effect of Abusive Supervision on Employee Job Performance: The Moderating Role of Employment Contract Type. J. Bus. Ethics 2024. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, C.; DiazGranados, D.; Salas, E.; Le, H.; Burke, C.S.; Lyons, R.; Goodwin, G.F. Does Team Building Work? Small Group Res. 2009, 40, 181–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catharina, V.; Suzanne van, G.; Niels Van, Q.; Steven, L.G.; Tilman, E. Proactivity at Work: The Roles of Respectful Leadership and Leader Group Prototypicality. J. Pers. Psychol. 2021, 20, 114–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.-H.; Wang, Z. How Transformational Leadership Shapes Team Proactivity: The Mediating Role of Positive Affective Tone and the Moderating Role of Team Task Variety. Group Dyn. Theory Res. Pract. 2015, 19, 137–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, J.R.; Cochrane, R.A. Goals-and-Methods Matrix: Coping with Projects with Ill Defined Goals and/or Methods of Achievin Them. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 1993, 11, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tims, M.; Parker, S.K. How Coworkers Attribute, React to, and Shape Job Crafting. Organ. Psychol. Rev. 2020, 10, 29–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Baruch, Y.; Shih, W. Corporate Social Responsibility and Team Performance: The Mediating Role of Team Efficacy and Team Self-Esteem. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 108, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; An, Y.; Wang, L.; Zheng, C. Newcomers’ Reaction to the Abusive Supervision toward Peers during Organizational Socialization. J. Vocat. Behav. 2021, 128, 103586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zang, D.; Liu, C.; Jiao, Y. Abusive Supervision, Affective Commitment, Customer Orientation, and Proactive Customer Service Performance: Evidence from Hotel Employees in China. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 648090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barczak, G.; Lassk, F.; Mulki, J. Antecedents of Team Creativity: An Examination of Team Emotional Intelligence, Team Trust and Collaborative Culture. Creat. Innov. Manag. 2010, 19, 332–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, W.; Sun, L.-Y.; Lam, L.W. Employee–Organization Exchange and Employee Creativity: A Motivational Perspective. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2020, 31, 385–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, W.; Sun, L.-Y. Do Victims Really Help Their Abusive Supervisors? Reevaluating the Positive Consequences of Abusive Supervision. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, Z.; Wu, N.; Yue, T.; Jie, J.; Hou, G.; Fu, A. How Leader-Member Exchange Affects Creative Performance: An Examination From the Perspective of Self-Determination Theory. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 573793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, H.; Brown, D.J.; Ferris, D.L.; Liang, L.H.; Keeping, L.M.; Morrison, R. Abusive Supervision and Retaliation: A Self-Control Framework. Acad. Manag. J. 2014, 57, 116–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, W.; Sun, L.; Sun, L.-Y.; Li, C.; Leung, A.S.M. Abusive Supervision and Job-Oriented Constructive Deviance in the Hotel Industry: Test of a Nonlinear Mediation and Moderated Curvilinear Model. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 30, 2249–2267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Teng, R.; Zhou, L.; Wang, V.L.; Yuan, J. Abusive Supervision, Leader-Member Exchange, and Creativity: A Multilevel Examination. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 647169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, C.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, J.; Liu, S. Abusive Supervision and Employee Creativity: A Moderated Mediation Model. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2020, 41, 193–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousseau, V.; Aubé, C. When Leaders Stifle Innovation in Work Teams: The Role of Abusive Supervision. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 151, 651–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atwater, L.; Kim, K.Y.; Witt, A.; Latheef, Z.; Callison, K.; Elkins, T.J.; Zheng, D. Reactions to Abusive Supervision: Examining the Roles of Emotions and Gender in the USA. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2016, 27, 1874–1899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Zhang, P.; Liao, J.; Hao, P.; Mao, J. Abusive Supervision and Employee Creativity: The Mediating Role of Psychological Safety and Organizational Identification. Manag. Decis. 2016, 54, 130–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafferty, A.E.; Restubog, S.L.D. The Influence of Abusive Supervisors on Followers’ Organizational Citizenship Behaviours: The Hidden Costs of Abusive Supervision. Br. J. Manag. 2011, 22, 270–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallett, T. Emotional Feedback and Amplification in Social Interaction. Sociol. Q. 2003, 44, 705–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marks, M.A.; Mathieu, J.E.; Zaccaro, S.J. A Temporally Based Framework and Taxonomy of Team Processes. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2001, 26, 356–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y.; Eom, C. Team Proactivity as a Linking Mechanism between Team Creative Efficacy, Transformational Leadership, and Risk-Taking Norms and Team Creative Performance. J. Creat. Behav. 2014, 48, 89–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, H.M.; Parker, S.K.; Turner, N. Proactively Performing Teams: The Role of Work Design, Transformational Leadership, and Team Composition. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2010, 83, 301–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junker, T.L.; Bakker, A.B.; Gorgievski, M.J.; Derks, D. Agile Work Practices and Employee Proactivity: A Multilevel Study. Hum. Relat. 2022, 75, 2189–2217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Liu, X. Linking Team-Member Exchange Differentiation to Team Creativity. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2020, 41, 208–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salas, E.; Priest, H.A.; DeRouin, R.E. Team Building. In Handbook of Human Factors and Ergonomics Methods; Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Salas, E.; Rozell, D.; Mullen, B.; Driskell, J.E. The Effect of Team Building on Performance: An Integration. Small Group Res. 1999, 30, 309–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pervaiz, S.; Li, G.; He, Q. The Mechanism of Goal-Setting Participation’s Impact on Employees’ Proactive Behavior, Moderated Mediation Role of Power Distance. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0260625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maden-Eyiusta, C. Role Conflict, Role Ambiguity, and Proactive Behaviors: Does Flexible Role Orientation Moderate the Mediating Impact of Engagement? Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2021, 32, 2829–2855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Salvi, C.; Becker, M.; Beeman, M. Solving Problems with an Aha! Increases Risk Preference. Think. Reason. 2023. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; Li, Z.; Khan, S.; Shah, S.J.; Ullah, R. Linking Humble Leadership and Project Success: The Moderating Role of Top Management Support with Mediation of Team-Building. Int. J. Manag. Proj. Bus. 2021, 14, 545–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, L. Mediating Toxic Emotions in the Workplace the Impact of Abusive Supervision. J. Nurs. Manag. 2013, 22, 953–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiefer, T.; Barclay, L.J. Understanding the Mediating Role of Toxic Emotional Experiences in the Relationship between Negative Emotions and Adverse Outcomes. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2012, 85, 600–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauchamp, M.R.; McEwan, D.; Waldhauser, K.J. Team Building: Conceptual, Methodological, and Applied Considerations. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2017, 16, 114–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Ferris, G.R.; Xu, J.; Weitz, B.A.; Perrewé, P.L. When Ingratiation Backfires: The Role of Political Skill in the Ingratiation–Internship Performance Relationship. Acad. Manag. Learn. Educ. 2014, 13, 569–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; Organ, D.W. Self-Reports in Organizational Research: Problems and Prospects. J. Manag. 1986, 12, 531–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brislin, R.W. Back-Translation for Cross-Cultural Research. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 1970, 1, 185–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozlowski, S.W.J.; Klein, K.J. Multilevel Theory, Research and Methods in Organizations: Foundations, Extensions, and New Directions, 1st ed.; Jossey-Bass (Wiley): Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Bateman, T.S.; Crant, J.M. The Proactive Component of Organizational Behavior: A Measure and Correlates. J. Organ. Behav. 1993, 14, 103–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leblanc, P.; Rousseau, V.; Harvey, J. Leader Humility and Team Innovation: The Role of Team Reflexivity and Team Proactive Personality. J. Organ. Behav. 2022, 43, 1396–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dulaimi, M.F.; Nepal, M.P.; Park, M. A Hierarchical Structural Model of Assessing Innovation and Project Performance. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2005, 23, 565–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rego, A.; Sousa, F.; Pina E Cunha, M.; Correia, A.; Saur-Amaral, I. Leader Self-Reported Emotional Intelligence and Perceived Employee Creativity: An Exploratory Study. Creat. Innov. Manag. 2007, 16, 250–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritz, C.; Van Knippenberg, D. Gender and Leadership Aspiration: Supervisor Gender, Support, and Job Control. Appl. Psychol. 2020, 69, 741–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Aiken, L.S.; West, S.G. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions. Statistician 1991, 43, 453–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, L.R.; Demaree, R.G.; Wolf, G. Estimating Within-Group Interrater Reliability with and without Response Bias. J. Appl. Psychol. 1984, 69, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bliese, P.D. Within-Group Agreement, Non-Independence, and Reliability: Implications for Data Aggregation and Analysis; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Han, J.H.; Liao, H.; Han, J.; Li, A.N. When Leader–Member Exchange Differentiation Improves Work Group Functioning: The Combined Roles of Differentiation Bases and Reward Interdependence. Pers. Psychol. 2021, 74, 109–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Bliese, P.D. The Role of Different Levels of Leadership in Predicting Self- and Collective Efficacy: Evidence for Discontinuity. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 549–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthén, L.K.; Muthén, B.O. Mplus User’s Guide; Muthén & Muthén: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, L.J.; Vandenberg, R.J.; Edwards, J.R. 12 Structural Equation Modeling in Management Research: A Guide for Improved Analysis. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2009, 3, 543–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, T.D.; Rhemtulla, M.; Gibson, K.; Schoemann, A.M. Why the Items versus Parcels Controversy Needn’t Be One. Psychol. Methods 2013, 18, 285–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, U.A.; Anantatmula, V. Psychological Safety Effects on Knowledge Sharing in Project Teams. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2023, 70, 3876–3886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, L.; Ji, Y.P.; Wu, C.; Ning, X.; He, Y. Relationship between Abusive Supervision and Workers’ Well-Being in Construction Projects: Effects of Guanxi Closeness and Trust in Managers. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2023; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Gu, Q. How Abusive Supervision and Abusive Supervisory Climate Influence Salesperson Creativity and Sales Team Effectiveness in China. Manag. Decis. 2016, 54, 455–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, K.W.T.; Au, A.K.C.; Cooper-Thomas, H.D.; Aw, S.S.Y. The Effect of Learning Goal Orientation and Communal Goal Strivings on Newcomer Proactive Behaviours and Learning. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2016, 89, 420–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afridi, S.A.; Afsar, B.; Shahjehan, A.; Khan, W.; Rehman, Z.U.; Khan, M.A.S. Impact of Corporate Social Responsibility Attributions on Employee’s Extra-role Behaviors: Moderating Role of Ethical Corporate Identity and Interpersonal Trust. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2023, 30, 991–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espedido, A.; Searle, B.J. Proactivity, Stress Appraisals, and Problem-Solving: A Cross-Level Moderated Mediation Model. Work Stress 2021, 35, 132–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twemlow, M.; Tims, M.; Khapova, S.N. A Process Model of Peer Reactions to Team Member Proactivity. Hum. Relat. 2023, 76, 1317–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, C.M.; Lucianetti, L.; Bhave, D.P.; Christian, M.S. “You Wouldn’t Like Me When I’m Sleepy”: Leaders’ Sleep, Daily Abusive Supervision, and Work Unit Engagement. Acad. Manag. J. 2015, 58, 1419–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tepper, B.J.; Simon, L.; Park, H.M. Abusive Supervision. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2017, 4, 123–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.53 | 0.33 | -- | ||||||

| 3.97 | 1.32 | −0.01 | -- | |||||

| 1.84 | 0.56 | 0.31 *** | −0.35 *** | 0.97 | ||||

| 5.81 | 0.36 | 0.00 | 0.22 * | −0.27 ** | 0.79 | |||

| 5.81 | 0.37 | −0.53 *** | 0.28 ** | −0.66 *** | 0.20 * | 0.83 | ||

| 5.81 | 0.27 | −0.22 * | 0.28 ** | −0.58 *** | 0.40 *** | 0.69 *** | 0.72 | |

| 5.54 | 0.52 | −0.27 ** | 0.36 *** | −0.35 *** | 0.56 *** | 0.39 *** | 0.52 *** | 0.94 |

| Variables | Team Proactive Behavior | Project Performance | Project Team Creativity | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | SE | b | SE | b | SE | b | SE | b | SE | b | SE | |

| Constant | 5.58 *** | 0.11 | 5.92 *** | 0.17 | 5.68 *** | 0.08 | 6.22 *** | 0.11 | 5.21 *** | 0.15 | 5.55 *** | 0.22 |

| Controls | ||||||||||||

| Team gender diversity | 0.01 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.10 | −0.18 ** | 0.07 | −0.04 | 0.06 | −0.43 ** | 0.13 | −0.34 * | 0.13 |

| Team size | 0.06 * | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.06 ** | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.14 *** | 0.03 | 0.12 *** | 0.03 |

| Independent variable | ||||||||||||

| Team abusive supervision | −0.16 ** | 0.06 | −0.25 *** | 0.04 | −0.16 * | 0.08 | ||||||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.03 * | 0.08 ** | 0.11 *** | 0.33 *** | 0.19 *** | 0.21 *** | ||||||

| Variables | Team Proactive Behavior | Project Performance | Project Team Creativity | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | SE | b | SE | b | SE | |

| Constant | 5.71 *** | 0.11 | 4.67 *** | 0.31 | 1.22 ** | 0.58 |

| Controls | ||||||

| Team gender diversity | 0.19 | 0.11 | −0.06 | 0.06 | −0.41 *** | 0.11 |

| Team size | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.09 *** | 0.03 |

| Independent variable | ||||||

| Team abusive supervision | −0.11 | 0.07 | −0.22 *** | 0.04 | −0.05 | 0.07 |

| Mediator | ||||||

| Team proactive behavior | 0.19 ** | 0.05 | 0.72 *** | 0.10 | ||

| Moderator | ||||||

| Team building | 0.14 | 0.12 | ||||

| Interactions | ||||||

| Team abusive supervision × Team building | 0.64 ** | 0.20 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhou, Q.; Zhang, H.; Wu, Q.; Sampaio, S.; Zouggar, A.; Cormican, K. From Struggle to Strength: Coping with Abusive Supervision in Project Teams through Proactive Behavior and Team Building. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 456. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14060456

Zhou Q, Zhang H, Wu Q, Sampaio S, Zouggar A, Cormican K. From Struggle to Strength: Coping with Abusive Supervision in Project Teams through Proactive Behavior and Team Building. Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 14(6):456. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14060456

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhou, Qiwei, Hang Zhang, Qiong Wu, Suzana Sampaio, Anne Zouggar, and Kathryn Cormican. 2024. "From Struggle to Strength: Coping with Abusive Supervision in Project Teams through Proactive Behavior and Team Building" Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 6: 456. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14060456

APA StyleZhou, Q., Zhang, H., Wu, Q., Sampaio, S., Zouggar, A., & Cormican, K. (2024). From Struggle to Strength: Coping with Abusive Supervision in Project Teams through Proactive Behavior and Team Building. Behavioral Sciences, 14(6), 456. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14060456