Secondary Female Anorgasmia in Patients with Obsessive Traits: A Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

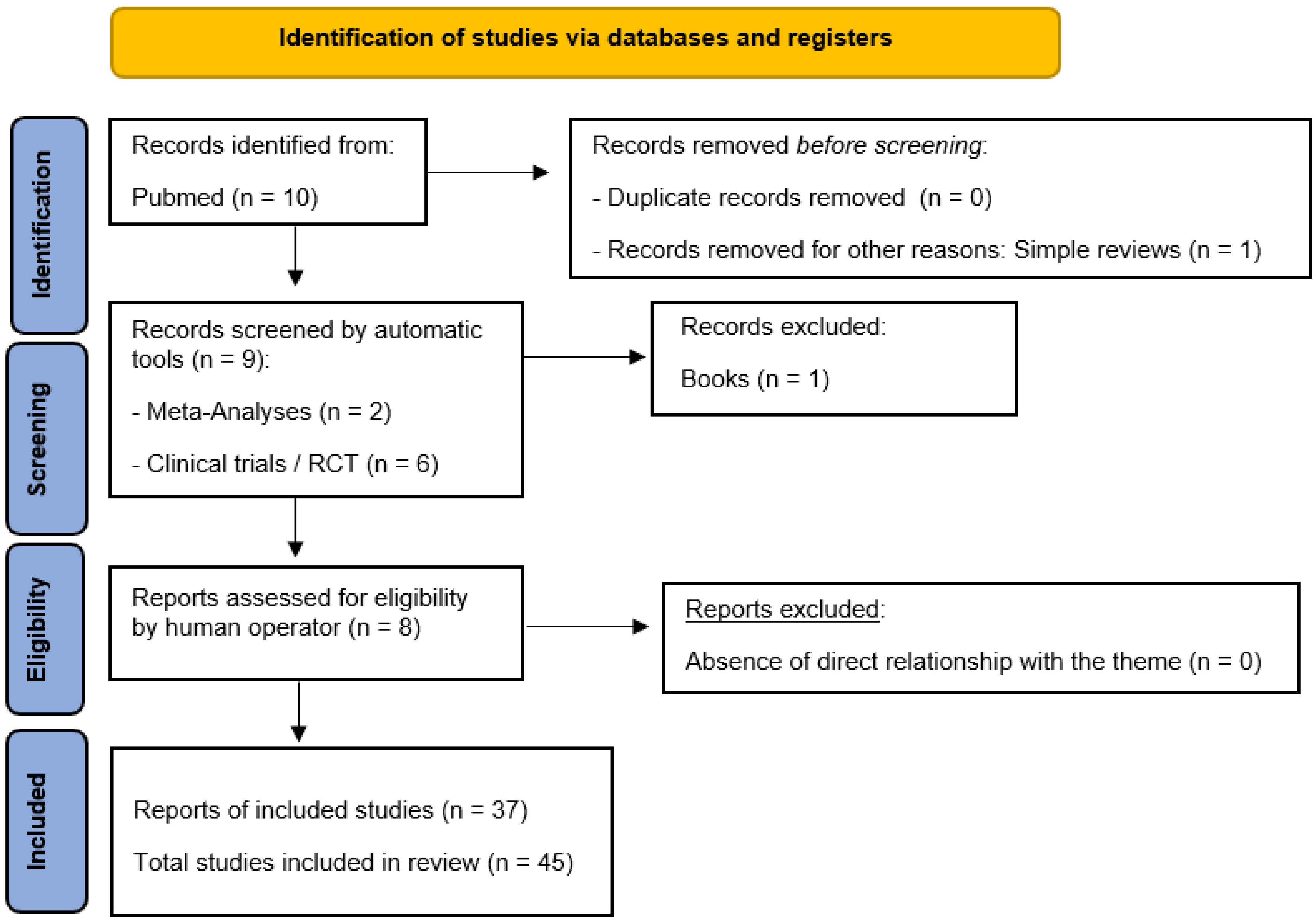

2. Materials and Methods

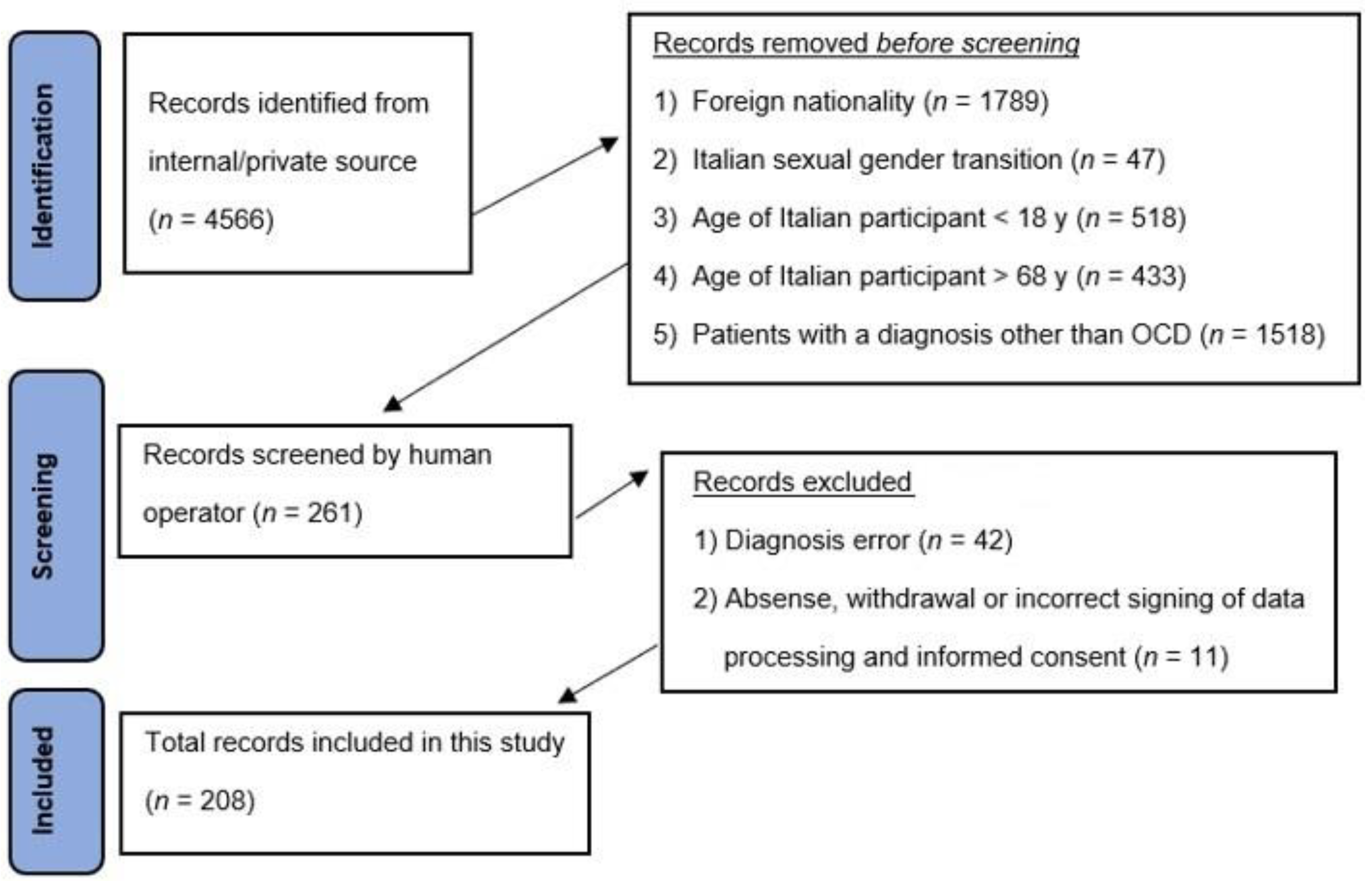

3. Setting and Participants

4. Results

- There were 261 subjects who underwent PICI-3 [42] for dysfunctional traits, to check whether the previous diagnosis of obsessive–compulsive disorder was confirmed or not, but 42 (16.1%) were excluded due to a misdiagnosis or change in diagnosis, and 11 (4.2%) due to legal reasons, arriving at a total of 208 confirmed subjects. Of the 208 participants who completed this study, exactly half (104/208, 50%) were found to have a personality profile characterized by at least five dysfunctional personality traits of the obsessive type, while the other half had at least five dysfunctional personality traits of other types (in particular and in descending order, bipolar disorder and psychotic disorders, then masochistic disorder, depressive disorder, anxiety disorder, dipendant disorder, and manic disorder), with the obsessive traits in a secondary or tertiary position.

- Using strategic language and PHEM-2 during the interview [41], the totality of the final selected population sample (208/208, 100%), both in the first and second groups, showed a complete distress orientation, expressing feelings such as anger, frustration, fear, and disappointment, with the presence of stressogenic events typical of their clinical condition of AO. Specifically, independently of the primary diagnosis, the totality of the sample reported that the obsessive symptomatology related to the inability to achieve orgasm, whether alone during masturbation or in a single or paired penetrative act, was constant, generating high levels of expectation and then disillusionment, which, as in a self-fulfilling prophecy, returns to the impossibility of achieving orgasm, resetting the libido. There was no statistically significant difference in this regard between the two groups.

- The administration of the Perrotta Individual Sexual Matrix Questionnaire (PSM-Q) [43] found 100% positivity in the overall sample (208/208) regarding the persistence of the anorgasmic condition, in both groups with no statistically significant differences. It imputed one-fifth (42/208) of the cases to be the result of moderate-to-severe psychological disorders (with a slight quantitative tendency toward the obsessive–compulsive disorder group, 25/42, 60%); this was followed by feelings of guilt and shame, excessive control, distrust of the relationship as a result of facts or events that produced disappointment and were able to negatively affect mutual esteem and respect, lack of confidence with the partner and sex, and physical ailments. Specific phobias seemed to be the least impactful category, reflecting the fact that the phobic component often combines with the obsessive component, reinforcing each other.

5. Discussions and Limits

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Lamont, J.; Bajzak, K.; Bouchard, C.; Burnett, M.; Byers, S.; Cohen, T.; Fisher, W.; Holzapfel, S.; Senikas, V. Female sexual health consensus clinical guidelines. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Can. 2012, 34, 769–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchand, E. Psychological and Behavioral Treatment of Female Orgasmic Disorder. Sex Med. Rev. 2021, 9, 194–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubowitch, E.; Khurgin, J. Cultural anorgasmia: Considerations in the evaluation of male infertility in the Hasidic community. Can. J. Urol. 2019, 26, 9864–9866. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- American Psychiatric Association (APA). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; DSM, text rev. APA: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, L.C.; Mulhall, J.P. Delayed orgasm and anorgasmia. Fertil. Steril. 2015, 104, 1082–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Sante, S.; Mollaioli, D.; Gravina, G.L.; Ciocca, G.; Limoncin, E.; Carosa, E.; Lenzi, A.; Jannini, E.A. Epidemiology of delayed ejaculation. Transl. Androl. Urol. 2016, 5, 541–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redelman, M. A general look at female orgasm and anorgasmia. Sex Health 2006, 3, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Litner, J. Encyclopedia of Couple and Family Therapy; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, H.S. The Illustrated Manual of Sex Therapy; Brunner/Mazel Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- IsHak, W.W.; Bokarius, A.; Jeffrey, J.K.; Davis, M.C.; Bakhta, Y. Disorders of Orgasm in Women: A Literature Review of Etiology and Current Treatments. J. Sex Med. 2010, 7, 3254–3268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csoka, A.; Bahrick, A.; Mehtonen, O.P. Persistent Sexual Dysfunction after Discontinuation of Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors. J. Sex. Med. 2008, 5, 227–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonelli, C.; Fabrizi, A.; Rossi, R. Sessuologia Clinica; Franco Angeli: Milan, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman, K.R.; Coluccio, M.; Linke, M.; Noonan, E.; Babalola, R.; Aziz, R. Alprazolam-induced dose-dependent anorgasmia: Case analysis. BJPsych Open 2018, 4, 274–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, M.D. Fluoxetine and anorgasmia. Am. J. Psychiatry 1989, 146, 804–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, J.N. Anorgasmia caused by an MAOI. Am. J. Psychiatry 1987, 144, 527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Price, J.; Grunhaus, L.J. Treatment of clomipramine-induced anorgasmia with yohimbine: A case report. J. Clin. Psychiatry 1990, 51, 32–33. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Németh, A.; Aratò, M.; Treuer, T. Treatment of fluvoxamine-induced anorgasmia with a partial drug holiday. Am. J. Psychiatry 1996, 153, 1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aizenberg, D.; Naor, S.; Zemishlany, Z.; Weizman, A. The serotonin antagonist mianserin for treatment of serotonin reuptake inhibitor-induced sexual dysfunction in women: An open-label add-on study. Clin. Neuropharmacol. 1999, 22, 347–350. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Giustozzi, A.A. Sexual dysfunction in women. In Ferri FF. Ferri’s Clinical Advisor 2010; Mosby: St. Louis, MO, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Perrotta, G. Anxiety disorders: Definitions, contexts, neural correlates and strategic therapy. J. Neur. Neurosci. 2019, 6, 42. [Google Scholar]

- Geore Nurnberg, H. Sildenafil for Women Patients with Antidepressant-Induced Sexual Dysfunction. Psychiatr. Serv. 1999, 50, 1076–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrotta, G. Panic Disorder: Definitions, Contexts, Neural Correlates and Clinical Strategies. Curr. Tr. Clin. Med. Sci. 2019, 1, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrotta, G. Depressive disorders: Definitions, contexts, differential diagnosis, neural correlates and clinical strategies. Arch. Depress. Anxiety 2019, 5, 9–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrotta, G. Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: Definition, contexts, neural correlates and clinical strategies. J. Neurol. 2019, 1, 8–16. [Google Scholar]

- Perrotta, G. Psychological trauma: Definition, clinical contexts, neural correlations and therapeutic approaches. Curr. Res. Psychiatry Brain Disord. 2020, 2019, CRPBD-100006. [Google Scholar]

- Trager, R.J.; Baumann, A. Improvement of Anorgasmia and Anejaculation After Spinal Manipulation in an Older Man With Lumbar Stenosis: A Case Report. Cureus 2023, 15, e34719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hull, E.M.; Lorrain, D.S.; Du, J.; Matuszewich, L.; A Lumley, L.; Putnam, S.K.; Moses, J. Hormone-neurotransmitter interactions in the control of sexual behavior. Behav. Brain Res. 1999, 105, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavlicev, M.; Zupan, A.M.; Barry, A.; Walters, S.; Milano, K.M.; Kliman, H.J.; Wagner, G.P. An experimental test of the ovulatory homolog model of female orgasm. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 20267–20273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piontek, A.; Szeja, J.; Błachut, M.; Badura-Brzoza, K. Sexual problems in the patients with psychiatric disorders. Wiad Lek 2019, 72, 1984–1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aksoy, U.M.; Aksoy, S.G.; Maner, F.; Gokalp, P.; Yanik, M. Sexual dysfunction in obsessive compulsive disorder and panic disorder. Psychiatr. Danub. 2012, 24, 381–385. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Meloy, T.S.; Southern, J.P. Neurally augmented sexual function in human females: A preliminary investigation. Neuromodulation 2006, 9, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flannigan, R.; Heier, L.; Voss, H.; Chazen, J.L.; Paduch, D.A. Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging Detects Between-Group Differences in Neural Activation Among Men with Delayed Orgasm Compared with Normal Controls: Preliminary Report. J. Sex Med. 2019, 16, 1246–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barak, Y.; Achiron, A.; Elizur, A.; Gabbay, U.; Noy, S.; Sarova-Pinhas, I. Sexual dysfunction in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: Magnetic resonance imaging, clinical, and psychological correlates. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 1996, 21, 255–258. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Meston, C.M.; Levin, R.J.; Sipski, M.L.; Hull, E.M.; Heiman, J.R. Women’s orgasm. Annu. Rev. Sex Res. 2004, 15, 173–257. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wise, N.J.; Frangos, E.; Komisaruk, B.R. Brain Activity Unique to Orgasm in Women: An fMRI Analysis. J. Sex Med. 2017, 14, 1380–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robbins, T.W.; Vaghi, M.M.; Banca, P. Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: Puzzles and Prospects. Neuron 2019, 102, 27–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakao, T.; Okada, K.; Kanba, S. Neurobiological model of obsessive-compulsive disorder: Evidence from recent neuropsychological and neuroimaging findings. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2014, 68, 587–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmari, S.E.; Rauch, S.L. The prefrontal cortex and OCD. Neuropsychopharmacology 2022, 47, 211–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rauch, S.L.; Britton, J.C. Developmental neuroimaging studies of OCD: The maturation of a field. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2010, 49, 1186–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basiletti, V.; Basiletti, V.; Eleuteri, S. The “Human Emotions” and the new “Perrotta Human Emotions Model” (PHEM-2): Structural and functional updates to the first model. Open J. Trauma 2023, 7, 022–034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrotta, G. Perrotta Integrative Clinical Interviews 3 (PICI-3): Development, regulation, updation, and validation of the psychometric instrument for the identification of functional and dysfunctional personality traits and diagnosis of psychopathological disorders, for children (8–10 years), preadolescents (11–13 years), adolescents (14–18 years), adults (19–69 years), and elders (70–90 years). Ibrain 2024, 10, 146–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrotta, G. “Perrotta Individual Sexual Matrix Questionnaire” (PSM-Q): Technical updates and clinical research. Int. J. Sex Reprod. Health Care 2021, 4, 062–066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrotta, G. The strategic clinical model in psychotherapy: Theoretical and practical profiles. J. Addict. Adolesc. Behav. 2020, 3, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espugnatore, G.; Fabiano, G.; Gentili, S.; Perrotta, G.; Pillon, P.; Zaffino, A. La Psicoterapia Strategica Nella Pratica Clinica; Primiceri Editore: Padua, Italy, 2023. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | N | M ± SD or % |

|---|---|---|

| Total Age (18–68 y) | 208 | 39.05 ± 14.62 |

| Age_18–27 y | 65 | 31.2% |

| Age_28–37 y | 35 | 16.8% |

| Age_38–47 y | 41 | 19.7% |

| Age_48–57 y | 39 | 18.8% |

| Age_58–68 y | 28 | 13.5% |

| Patients with a clinical diagnosis of OCD without comorbidities | 104 | 50.0% |

| Patients with a clinical diagnosis of OCD with comorbidities | 104 | 50.0% |

| PICI-3_1_anxiety disorder | 14 | 13.5% |

| PICI-3_2_maniac disorder | 8 | 7.7% |

| PICI-3_3_depressive disorder | 15 | 14.4% |

| PICI-3_4_bipolal disorder | 20 | 19.2% |

| PICI-3_5_dependence disorder | 9 | 8.7% |

| PICI-3_6_masochistic disorder | 18 | 17.3% |

| PICI-3_7_psychopathic disorder | 20 | 19.2% |

| PSM-Q_1_control | 20 | 9.6% |

| PSM-Q_2_distrust | 20 | 9.6% |

| PSM-Q_3_low_confidence | 19 | 9.1% |

| PSM-Q_4_guilt/shame | 30 | 14.4% |

| PSM-Q_5_physical_dysfunctions | 20 | 9.6% |

| PSM-Q_6_mental_dysfunctions | 39 | 18.8% |

| PSM-Q_7_specific_phobias | 9 | 4.3% |

| PSM-Q_8_no_attraction | 10 | 4.8% |

| PSM-Q_9_childhood_sexual_abuse | 11 | 5.4% |

| PSM-Q_10_stressful life | 10 | 4.8% |

| PSM-Q_11_sexual_concerns | 10 | 4.8% |

| PSM-Q_12_unresolved_couple_problems | 10 | 4.8% |

| Variable Comparison | F | t | CI (min) | CI (max) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OCD_pure—PSM-Q_1_control | 0.88 | 0.49 | −0.06 | 0.10 | 0.642 |

| OCD_pure—PSM-Q_2_distrust | 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.08 | 0.08 | 1.000 |

| OCD_pure—PSM-Q_3_low_confidence | 0.23 | −0.24 | −0.09 | 0.07 | 0.811 |

| OCD_pure—PSM-Q_4_guilt/shame | 0.62 | 0.39 | −0.08 | 0.12 | 0.702 |

| OCD_pure—PSM-Q_5_physical_dysfunctions | 0.23 | 0.24 | −0.07 | 0.09 | 0.814 |

| OCD_pure—PSM-Q_6_mental_dysfunctions | 1.13 | −0.53 | −0.14 | 0.08 | 0.606 |

| OCD_pure—PSM-Q_7_specific_phobias | 0.46 | −0.34 | −0.06 | 0.05 | 0.730 |

| OCD_pure—PSM-Q_8_no_attraction | 1.68 | 0.65 | −0.04 | 0.08 | 0.526 |

| OCD_pure—PSM-Q_9_childhood_sexual_abuse | 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.06 | 0.06 | 1.000 |

| OCD_pure—PSM-Q_10_stressful life | 1.68 | 0.60 | −0.08 | 0.04 | 0.520 |

| OCD_pure—PSM-Q_11_sexual_concerns | 1.68 | 0.65 | −0.08 | 0.04 | 0.520 |

| OCD_pure—PSM-Q_12_unresolved_couple_problems | 1.68 | 0.65 | −0.04 | 0.08 | 0.520 |

| OCD_comb—PSM-Q_1_control | 0.88 | −0.47 | −0.10 | 0.06 | 0.640 |

| OCD_comb—PSM-Q_2_distrust | 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.08 | 0.08 | 1.000 |

| OCD_comb—PSM-Q_3_low_confidence | 0.23 | 0.24 | −0.07 | 0.09 | 0.811 |

| OCD_comb—PSM-Q_4_guilt/shame | 0.62 | −0.39 | −0.12 | 0.08 | 0.695 |

| OCD_comb—PSM-Q_5_physical_dysfunctions | 0.23 | −0.24 | −0.09 | 0.07 | 0.811 |

| OCD_comb—PSM-Q_6_mental_dysfunctions | 1.13 | 0.53 | −0.08 | 0.14 | 0.596 |

| OCD_comb—PSM-Q_7_specific_phobias | 0.46 | 0.34 | −0.05 | 0.06 | 0.735 |

| OCD_comb—PSM-Q_8_no_attraction | 1.68 | −0.65 | −0.08 | 0.04 | 0.519 |

| OCD_comb—PSM-Q_9_childhood_sexual_abuse | 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.06 | 0.06 | 1.000 |

| OCD_comb—PSM-Q_10_stressful life | 1.68 | 0.65 | −0.04 | 0.08 | 0.519 |

| OCD_comb—PSM-Q_11_sexual_concerns | 1.68 | 0.65 | −0.04 | 0.08 | 0.519 |

| OCD_comb—PSM-Q_12_unresolved_couple_problems | 1.68 | 0.65 | −0.08 | 0.04 | 0.519 |

| Variable Comparison | F | t | CI (min) | CI (max) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OCD_pure—PICI-3_1_anx | 0.000 | 0.000 | −0.073 | 0.073 | 1.000 |

| OCD_pure—PICI-3_2_maniac | 0.000 | 0.000 | −0.073 | 0.073 | 1.000 |

| OCD_pure—PICI-3_3_depres | 0.000 | 0.000 | −0.073 | 0.073 | 1.000 |

| OCD_pure—PICI-3_4_bipol | 0.000 | 0.000 | −0.069 | 0.069 | 1.000 |

| OCD_pure—PICI-3_5_dep | 1.222 | 0.551 | −0.050 | 0.088 | 0.582 |

| OCD_pure—PICI-3_6_masoc | 0.000 | 0.000 | −0.069 | 0.069 | 1.000 |

| OCD_pure—PICI-3_7_psicot | 0.000 | 0.000 | −0.069 | 0.069 | 1.000 |

| OCD_comb—PICI-3_1_anx | 0.000 | 0.000 | −0.073 | 0.073 | 1.000 |

| OCD_comb—PICI-3_2_maniac | 0.000 | 0.000 | −0.073 | 0.073 | 1.000 |

| OCD_comb—PICI-3_3_depres | 0.000 | 0.000 | −0.073 | 0.073 | 1.000 |

| OCD_comb—PICI-3_4_bipol | 0.000 | 0.000 | −0.069 | 0.069 | 1.000 |

| OCD_comb—PICI-3_5_dep | 1.222 | −0.551 | −0.088 | 0.050 | 0.582 |

| OCD_comb—PICI-3_6_masoc | 0.000 | 0.000 | −0.069 | 0.069 | 1.000 |

| OCD_comb—PICI-3_7_psycot | 0.000 | 0.000 | −0.069 | 0.069 | 1.000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Perrotta, G.; Eleuteri, S. Secondary Female Anorgasmia in Patients with Obsessive Traits: A Study. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 953. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14100953

Perrotta G, Eleuteri S. Secondary Female Anorgasmia in Patients with Obsessive Traits: A Study. Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 14(10):953. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14100953

Chicago/Turabian StylePerrotta, Giulio, and Stefano Eleuteri. 2024. "Secondary Female Anorgasmia in Patients with Obsessive Traits: A Study" Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 10: 953. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14100953

APA StylePerrotta, G., & Eleuteri, S. (2024). Secondary Female Anorgasmia in Patients with Obsessive Traits: A Study. Behavioral Sciences, 14(10), 953. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14100953