Imagine Being Humble: Integrating Imagined Intergroup Contact and Cultural Humility to Foster Inclusive Intergroup Relations

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Imagined Intergroup Contact

1.2. Cultural Humility

1.3. The Current Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary Results

3.2. Main Results

4. Discussion

Limitations and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Turner, R.N.; Crisp, R.J.; Lambert, E. Imagining intergroup contact can improve intergroup attitudes. Group Process. Intergroup 2007, 10, 427–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crisp, R.J.; Turner, R.N. The imagined contact hypothesis. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 46, 125–182. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, E.; Crisp, R.J. A meta-analytic test of the imagined contact hypothesis. Group Process. Intergroup 2014, 17, 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dermody, N.; Jones, M.K.; Cumming, S.R. The failure of imagined contact in reducing explicit and implicit out-group prejudice toward male homosexuals. Curr. Psychol. 2013, 32, 261–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, R.A.; Ratliff, K.A.; Vianello, M.; Adams, R.B., Jr.; Bahník, Š.; Bernstein, M.J.; Bocian, K.; Brandt, M.J.; Brooks, B.; Brumbaugh, C.C.; et al. Investigating variation in replicability. Soc. Psychol. 2014, 45, 142–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hook, J.N.; Davis, D.E.; Owen, J.; Worthington, E.L., Jr.; Utsey, S.O. Cultural humility: Measuring openness to culturally diverse clients. J. Couns. Psychol. 2013, 60, 353–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AlSheddi, M. Humility and Bridging Differences: A Systematic Literature Review of Humility in Relation to Diversity. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 2020, 79, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visintin, E.P.; Rullo, M. Humble and kind: Cultural humility as a buffer of the association between social dominance orientation and prejudice. Societies 2021, 11, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rullo, M.; Visintin, E.P.; Milani, S.; Romano, A.; Fabbri, L. Stay humble and enjoy diversity: The interplay between intergroup contact and cultural humility on prejudice. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 2022, 87, 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allport, G.W. The Nature of Prejudice; Addison-Wesley: New York, NY, USA, 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Pettigrew, T.F.; Tropp, L.R. A meta-analytic test of intergroup contact theory. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2006, 90, 751–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vezzali, L.; Stathi, S. Using Intergroup Contact to Fight Prejudice and Negative Attitudes: Psychological Perspectives; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Al Ramiah, A.; Schmid, K.; Hewstone, M.; Floe, C. Why are all the White (Asian) kids sitting together in the cafeteria? Resegregation and the role of intergroup attributions and norms. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2015, 54, 100–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dixon, J.; Tredoux, C.; Durrheim, K.; Finchilescu, G.; Clack, B. ‘The inner citadels of the color line’: Mapping the micro-ecology of racial segregation in everyday life spaces. Soc. Pers. Psychol. Compass 2008, 2, 1547–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paolini, S.; Harris, N.C.; Griffin, A.S. Learning anxiety in interactions with the outgroup: Towards a learning model of anxiety and stress in intergroup contact. Group Process. Intergroup 2016, 19, 275–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephan, W.G.; Stephan, C.W. Intergroup anxiety. J. Soc. Issues 1985, 41, 157–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shook, N.J.; Fazio, R.H. Social network integration: A comparison of same-race and interracial roommate relationships. Group Process. Intergroup 2011, 14, 399–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephan, W.G. Intergroup anxiety: Theory, research, and practice. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2014, 18, 239–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlow, F.K.; Paolini, S.; Pedersen, A.; Hornsey, M.J.; Radke, H.R.; Harwood, J.; Rubin, M.; Sibley, C.G. The contact caveat: Negative contact predicts increased prejudice more than positive contact predicts reduced prejudice. Pers. Soc. Psychol. B 2012, 38, 1629–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, S.C.; Aron, A.; McLaughlin-Volpe, T.; Ropp, S.A. The extended contact effect: Knowledge of cross-group friendships and prejudice. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1997, 73, 73–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vezzali, L.; Hewstone, M.; Capozza, D.; Giovannini, D.; Wölfer, R. Improving intergroup relations with extended and vicarious forms of indirect contact. Eur. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 2014, 25, 314–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husnu, S.; Crisp, R.J. Elaboration enhances the imagined contact effect. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2010, 46, 943–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagotto, L.; Visintin, E.P.; De Iorio, G.; Voci, A. Imagined intergroup contact promotes cooperation through outgroup trust. Group Process. Intergroup 2013, 16, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vezzali, L.; Capozza, D.; Giovannini, D.; Stathi, S. Improving implicit and explicit intergroup attitudes using imagined contact: An experimental intervention with elementary school children. Group Process. Intergroup 2012, 15, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vezzali, L.; Birtel, M.D.; Di Bernardo, G.A.; Stathi, S.; Crisp, R.J.; Cadamuro, A.; Visintin, E.P. Don’t hurt my outgroup friend: A multifaceted form of imagined contact promotes intentions to counteract bullying. Group Process. Intergroup 2020, 23, 643–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigler, R.S.; Hughes, J.M. Reasons for skepticism about the efficacy of simulated social contact interventions. Am. Psychol. 2010, 65, 131–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Visintin, E.P.; Berent, J.; Green, E.G.; Falomir-Pichastor, J.M. The interplay between social dominance orientation and intergroup contact in explaining support for multiculturalism. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2019, 49, 319–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, K.; Hotchin, V.; Wood, C. Imagined contact can be more effective for participants with stronger initial prejudices. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2017, 47, 282–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunaev, J.L.; Brochu, P.M.; Markey, C.H. Imagine that! The effect of counterstereotypic imagined intergroup contact on weight bias. Health Psychol. 2018, 37, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamloo, S.E.; Carnaghi, A.; Piccoli, V.; Grassi, M.; Bianchi, M. Imagined intergroup physical contact improves attitudes toward immigrants. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, R.; Hewstone, M. An integrative theory of intergroup contact. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2005, 37, 255–343. [Google Scholar]

- Hewstone, M.; Brown, R. Contact is not enough: An intergroup perspective on the contact hypothesis. In Contact and Conflict in Intergroup Encounters; Hewstone, M., Brown, R., Eds.; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1986; pp. 1–44. [Google Scholar]

- Scarberry, N.C.; Ratcliff, C.D.; Lord, C.G.; Lanicek, D.L.; Desforges, D.M. Effects of individuating information on the generalization part of Allport’s contact hypothesis. Pers. Soc. Psychol. B 1997, 23, 1291–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voci, A.; Hewstone, M. Intergroup contact and prejudice toward immigrants in Italy: The mediational role of anxiety and the moderational role of group salience. Group Process. Intergroup 2003, 6, 37–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stathi, S.; Crisp, R.J.; Hogg, M.A. Imagining intergroup contact enables member-to-group generalization. Group. Dyn.-Theor. Res. 2011, 15, 275–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannou, M.; Hewstone, M.; Al Ramiah, A. Inducing similarities and differences in imagined contact: A mutual intergroup differentiation approach. Group Process. Intergroup 2017, 20, 427–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visintin, E.P.; Birtel, M.D.; Crisp, R.J. The role of multicultural and colorblind ideologies and typicality in imagined contact interventions. Int. J. Intercult. Rel. 2017, 59, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tervalon, M.; Murray-Garcia, J. Cultural humility versus cultural competence: A critical distinction in defining physician training outcomes in multicultural education. J. Health. Care Poor Underserv. 1998, 9, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foronda, C.; Baptiste, D.L.; Reinholdt, M.M.; Ousman, K. Cultural humility: A concept analysis. J. Transcult. Nurs. 2016, 27, 210–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foronda, C.; Prather, S.; Baptiste, D.L.; Luctkar-Flude, M. Cultural humility toolkit. Nurs. Educ. 2022, 47, 267–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Watkins Jr, C.E.; Hook, J.N.; Hodge, A.S.; Davis, C.W.; Norton, J.; Wilcox, M.M.; Davis, D.E.; DeBlaere, C.; Owen, J. Cultural humility in psychotherapy and clinical supervision: A research review. Couns. Psychother. Res. 2022, 22, 548–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Captari, L.E.; Shannonhouse, L.; Hook, J.N.; Aten, J.D.; Davis, E.B.; Davis, D.E.; Van Tongeren, D.; Hook, J.R. Prejudicial and welcoming attitudes toward Syrian refugees: The roles of cultural humility and moral foundations. J. Psychol. Theol. 2019, 47, 123–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Tongeren, D.R.; Stafford, J.; Hook, J.N.; Green, J.D.; Davis, D.E.; Johnson, K.A. Humility attenuates negative attitudes and behaviors toward religious out-group members. J. Posit. Psychol. 2016, 11, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choe, E.; Srisarajivakul, E.; Davis, D.E.; DeBlaere, C.; Van Tongeren, D.R.; Hook, J.N. Predicting attitudes towards lesbians and gay men: The effects of social conservatism, religious orientation, and cultural humility. J. Psychol. Theol. 2019, 47, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidanius, J.; Pratto, F. Social Dominance: An Intergroup Theory of Social Hierarchy and Oppression; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Pettigrew, T.F.; Tropp, L.R. How does intergroup contact reduce prejudice? Meta-analytic tests of three mediators. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2008, 38, 922–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, R.N.; West, K.; Christie, Z. Out-group trust, intergroup anxiety, and out-group attitude as mediators of the effect of imagined intergroup contact on intergroup behavioral tendencies. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2013, 43, E196–E205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visintin, E.P.; Voci, A.; Pagotto, L.; Hewstone, M. Direct, extended, and mass-mediated contact with immigrants in Italy: Their associations with emotions, prejudice, and humanity perceptions. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2017, 47, 175–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, T.D.; Cunningham, W.A.; Shahar, G.; Widaman, K.F. To parcel or not to parcel: Exploring the question, weighing the merits. Struct. Equ. Model. 2002, 9, 151–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Aguinis, H.; Edwards, J.R.; Bradley, K.J. Improving our understanding of moderation and mediation in strategic management research. Organ. Res. Methods 2017, 20, 665–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, P.J. College sophomores in the laboratory redux: Influences of a narrow data base on social psychology’s view of the nature of prejudice. Psychol. Inq. 2008, 19, 49–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swart, H.; Hewstone, M.; Christ, O.; Voci, A. Affective mediators of intergroup contact: A three-wave longitudinal study in South Africa. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2011, 101, 1221–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vezzali, L.; Giovannini, D.; Capozza, D. Longitudinal effects of contact on intergroup relations: The role of majority and minority group membership and intergroup emotions. J. Commun. Appl. Soc. 2010, 20, 462–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behaviour: Reactions and reflections. Psychol. Health 2011, 26, 1113–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, T.; Tybur, J.M.; van Vugt, M. Gendered outgroup prejudice: An evolutionary threat management perspective on anti-immigrant bias. Group Process. Intergroup 2021, 24, 177–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Culturally Humble Imagined Contact (n = 139) | Standard Imagined Contact (n = 169) | Control (n = 156) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intergroup anxiety | 2.52 (1.03) | 2.78 (1.10) | 2.74 (1.14) |

| Prejudice | 17.42 (18.80) | 19.15 (17.67) | 18.18 (16.69) |

| Future contact intentions | 5.71 (1.28) | 5.67 (1.19) | 5.55 (1.26) |

| Mean (SD) | 1 | 2 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Intergroup anxiety | 2.69 (1.10) | - | |

| 2. Prejudice | 18.31 (17.68) | 0.36 *** | - |

| 3. Future contact intentions | 5.64 (1.24) | −0.16 *** | −0.61 *** |

| Intergroup Anxiety | Prejudice | Future Contact Intentions | |

|---|---|---|---|

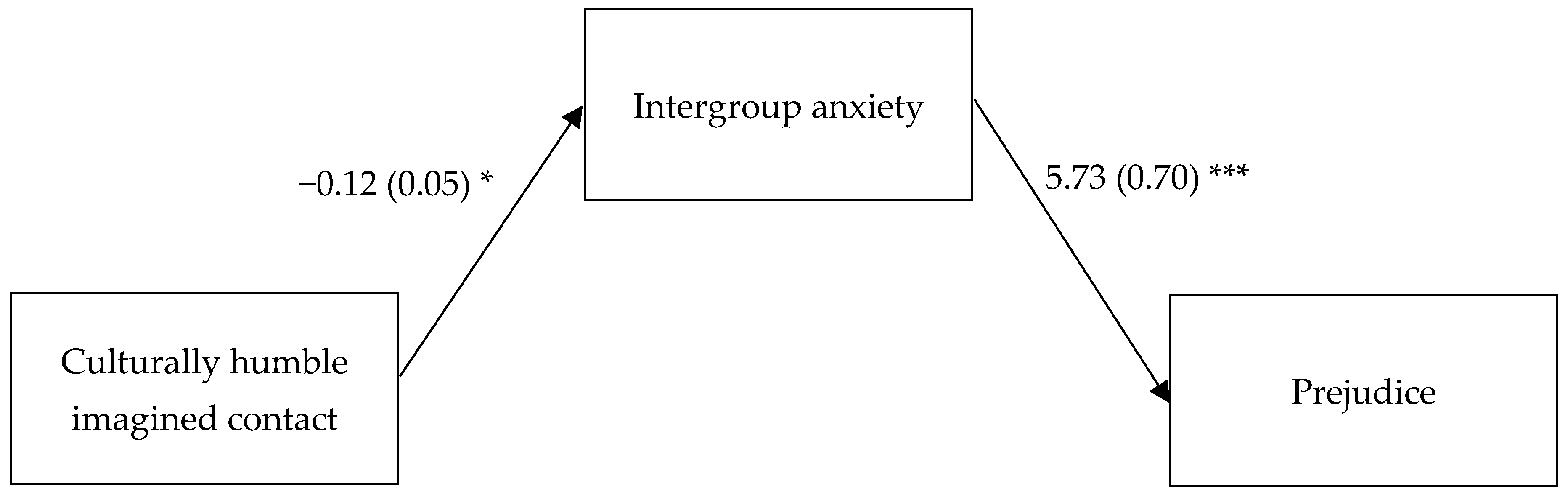

| Contrast 1 | −0.12 (0.05) * | 0.06 (0.84) | 0.03 (0.06) |

| Contrast 2 | 0.02 (0.06) | 0.37 (0.92) | 0.06 (0.07) |

| Intergroup anxiety | 5.73 (0.70) *** | −0.18 (0.05) *** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Visintin, E.P.; Rullo, M.; Lo Destro, C. Imagine Being Humble: Integrating Imagined Intergroup Contact and Cultural Humility to Foster Inclusive Intergroup Relations. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 51. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14010051

Visintin EP, Rullo M, Lo Destro C. Imagine Being Humble: Integrating Imagined Intergroup Contact and Cultural Humility to Foster Inclusive Intergroup Relations. Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 14(1):51. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14010051

Chicago/Turabian StyleVisintin, Emilio Paolo, Marika Rullo, and Calogero Lo Destro. 2024. "Imagine Being Humble: Integrating Imagined Intergroup Contact and Cultural Humility to Foster Inclusive Intergroup Relations" Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 1: 51. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14010051

APA StyleVisintin, E. P., Rullo, M., & Lo Destro, C. (2024). Imagine Being Humble: Integrating Imagined Intergroup Contact and Cultural Humility to Foster Inclusive Intergroup Relations. Behavioral Sciences, 14(1), 51. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14010051