Motivation to Avoid Uncertainty, Implicit Person Theories about the Malleability of Human Attributes and Attitudes toward Women as Leaders vs. Followers: A Mediational Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

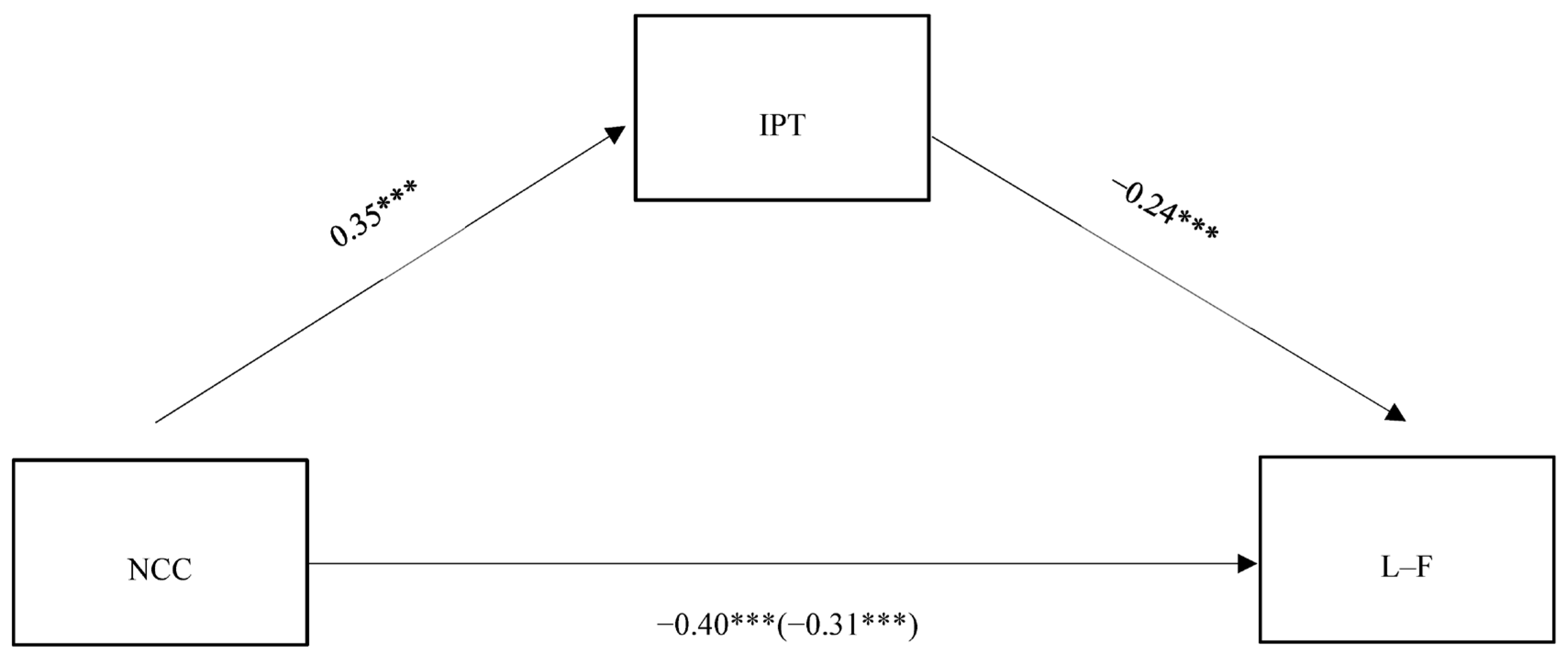

1.1. Need for Cognitive Closure, Implicit Person Theory, and Prejudiced Attitudes

1.2. The Present Research

2. Method

2.1. Sample Size Determination

2.2. Participants, Design, and Procedure

2.3. Measures

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Practical Implications

4.2. Limits and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Catalyst Quick Take: Statistical Overview of Women in the Workplace. Available online: http://www.catalyst.org/knowledge/statistical-overview-women-workplace (accessed on 9 September 2023).

- U.S. Women in Business. Available online: http://www.catalyst.org/publication/132/us-women-in-business (accessed on 9 September 2023).

- Elsesser, K.M. Gender bias against female leaders: A review. In Handbook on Well-Being of Working Women; Connerley, M.L., Wu, J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 161–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenig, A.M.; Eagly, A.H.; Mitchell, A.A.; Ristikari, T. Are leader stereotypes masculine? A meta-analysis of three research paradigms. Psychol. Bull. 2011, 137, 616–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javalgi, R.R.G.; Scherer, R.; Sánchez, C.; Pradenas Rojas, L.; Parada Daza, V.; Hwang, C.E.; Yan, W. A comparative analysis of the attitudes toward women managers in China, Chile, and the USA. Int. J. Bus. Emerg. Mark. 2011, 6, 233–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudman, L.A.; Fairchild, K. Reactions to counterstereotypic behavior: The role of backlash in cultural stereotype maintenance. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2004, 87, 157–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, S.; Stegmann, S.; Hernandez Bark, A.S.; Junker, N.M.; van Dick, R. Think manager—Think male, think follower—Think female: Gender bias in implicit followership theories. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2017, 47, 377–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruglanski, A.W. The Psychology of Closed Mindedness; Psychology Press: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Dweck, C.S.; Chiu, C.; Hong, Y. Implicit Theories and Their Role in Judgments and Reactions: A Word From Two Perspectives. Psychol. Inq. 1995, 6, 267–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roets, A.; Kruglanski, A.W.; Kossowska, M.; Pierro, A.; Hong, Y.Y. The motivated gatekeeper of our minds: New directions in need for closure theory and research. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2015, 52, 221–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagly, A.H.; Karau, S.J. Role congruity theory of prejudice toward female leaders. Psychol. Rev. 2002, 109, 573–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierro, A.; Kruglanski, A.W. Seizing and freezing on a significant-person schema: Need for closure and the transference effect in social judgment. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2008, 34, 1492–1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijksterhuis, A.P.; Van Knippenberg, A.D.; Kruglanski, A.W.; Schaper, C. Motivated social cognition: Need for closure effects on memory and judgment. J. Exp. Soc. 1996, 32, 254–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livi, S.; Kruglanski, A.W.; Pierro, A.; Mannetti, L.; Kenny, D.A. Epistemic motivation and perpetuation of group culture: Effects of need for cognitive closure on trans-generational norm transmission. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2015, 129, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roets, A.; Van Hiel, A. Allport’s prejudiced personality today: Need for closure as the motivated cognitive basis of prejudice. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2011, 20, 349–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jost, J.T.; Kruglanski, A.W.; Simon, L. Effects of epistemic motivation on conservatism, intolerance and other system-justifying attitudes. In Shared Cognition in Organizations: The Management of Knowledge; Thompson, L.L., Levine, J.M., Messnick, D.M., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2011; pp. 91–116. [Google Scholar]

- Kruglanski, A.W.; Pierro, A.; Mannetti, L.; De Grada, E. Groups as epistemic providers: Need for closure and the unfolding of group-centrism. Psychol. Rev. 2006, 113, 84–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albarello, F.; Mula, S.; Contu, F.; Baldner, C.; Kruglanski, A.W.; Pierro, A. Addressing the effect of concern with COVID-19 threat on prejudice towards immigrants: The sequential mediating role of need for cognitive closure and desire for cultural tightness. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 2023, 93, 101755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albarello, F.; Contu, F.; Baldner, C.; Vecchione, M.; Kruglanski, A.W.; Pierro, A. At the roots of Allport’s “prejudice-prone personality”: The impact of NFC on prejudice towards different outgroups and the mediating role of binding moral foundations. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 2023, 97, 101885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contu, F.; Ellenberg, M.; Kruglanski, A.W.; Pantaleo, G.; Pierro, A. Need for cognitive closure and desire for cultural tightness mediate the effect of concern about ecological threats on the need for strong leadership. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, G.A. The Psychology of Personal Constructs; Norton: New York, NY, USA, 1955. [Google Scholar]

- Heider, F. The Psychology of Interpersonal Relations; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1958. [Google Scholar]

- Kruglanski, A.W. Implicit theory of personality as a theory of personality. Psychol. Inq. 1995, 6, 301–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, S.R.; Stroessner, S.J.; Dweck, C.S. Stereotype formation and endorsement: The role of implicit theories. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1998, 74, 1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, C.Y.; Morris, M.W.; Hong, Y.Y.; Menon, T. Motivated cultural cognition: The impact of implicit cultural theories on dispositional attribution varies as a function of need for closure. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2000, 78, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, D.T.; Malone, P.S. The correspondence bias. Psychol. Bull. 1995, 117, 21–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunda, Z.; Nisbett, R.E. The psychometrics of everyday life. Cogn. Psychol. 1986, 18, 195–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ross, L.; Nisbett, R.E. The Person and the Situation: Perspectives of Social Psychology; Pinter & Martin Publishers: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Roets, A.; Van Hiel, A.; Dhont, K. Is sexism a gender issue? A motivated social cognition perspective on men’s and women’s sexist attitudes toward own and other gender. Eur. J. Pers. 2012, 26, 350–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, J.; Haidt, J.; Nosek, B.A. Liberals and conservatives rely on different sets of moral foundations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 96, 1029–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baldner, C.; Pierro, A. The trials of women leaders in the workforce: How a need for cognitive closure can influence acceptance of harmful gender stereotypes. Sex Roles 2009, 80, 565–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldner, C.; Pierro, A.; Di Santo, D.; Kruglanski, A.W. Men and women who want epistemic certainty are at-risk for hostility towards women leaders. J. Soc. Psychol. 2022, 162, 549–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viola, M.; Baldner, C.; Pierro, A. How and when need for cognitive closure impacts attitudes towards women managers (Cómo y cuándo la necesidad de cierre influye en las actitudes hacia las mujeres directivas). Int. J. Soc. Psychol. 2023, 38, 157–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastian, B.; Haslam, N. Immigration from the perspective of hosts and immigrants: Roles of psychological essentialism and social identity. Asian J. Soc. Psychol. 2008, 11, 127–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heyman, G.D.; Dweck, C.S. Children’s thinking about traits: Implications for judgments of the self and others. Child Dev. 1998, 69, 391–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdley, C.A.; Dweck, C.S. Children’s implicit personality theories as predictors of their social judgments. Child Dev. 1993, 64, 863–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoyt, C.L.; Burnette, J.L. Gender bias in leader evaluations: Merging implicit theories and role congruity perspectives. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2013, 39, 1306–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez Bark, A.S.; Escartin, J.; Schuh, S.C.; van Dick, R. Who leads more and why? A mediation model from gender to leadership role occupancy. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 139, 473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuh, S.C.; Hernandez Bark, A.; Van Quaquebeke, N.; Hossiep, R.; Frieg, P.; van Dick, R. Gender differences in leadership role occupancy: The mediating role of power motivation. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 120, 363–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heilman, M.E. Sex bias in work settings: The lack of fit model. In Research in Organizational Behavior; Staw, B., Cummings, L., Eds.; JAI Press: Greenwich, CT, USA, 1983; Volume 5, pp. 269–298. [Google Scholar]

- Heilman, M.E. Gender stereotypes and workplace bias. Res. Organ. Behav. 2012, 32, 113–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoemann, A.M.; Boulton, A.J.; Short, S.D. Determining power and sample size for simple and complex mediation models. Soc. Psychol. Pers. Sci. 2017, 8, 379–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierro, A.; Kruglanski, A.W. Revised Need for Cognitive Closure Scale; Università di Roma La Sapienza: Rome, Italy, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Plaks, J.E.; Stroessner, S.J.; Dweck, C.S.; Sherman, J.W. Person theories and attention allocation: Preferences for stereotypic versus counterstereotypic information. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 80, 876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatnagar, D.; Swamy, R. Attitudes toward women as managers: Does interaction make a difference? Hum. Relat. 1995, 48, 1285–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Baldner, C.; Viola, M.; Capozza, D.; Vezzali, L.; Kruglanski, A.W.; Pierro, A. Direct and imagined contact moderates the effect of need for cognitive closure on attitudes towards women managers. J. Commun. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2022, 32, 1061–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contu, F.; Tesi, A.; Aiello, A. Intergroup Contact Is Associated with Less Negative Attitude toward Women Managers: The Bolstering Effect of Social Dominance Orientation. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contu, F.; Aiello, A.; Pierro, A. Epistemic Uncertainty, Social Dominance Orientation, and Prejudices towardWomen in Leadership Roles: Mediation and Moderation Analyses. Soc. Sci. 2024, 13, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantaleo, G.; Contu, F. The dissociation between cognitive and emotional prejudiced responses to deterrents. Psychol. Hub 2021, 38, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allport, G. The Nature of Prejudice; Addison-Wesley: Reading, MA, USA, 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Muthi’ah, N.I.; Poerwandari, E.K.; Primasari, I. To be leader or not to be leader? Correlation between men’s negative presumption toward women leaders and women’s leadership aspirations. In Diversity in Unity: Perspectives from Psychology and Behavioral Sciences; Ariyanto, A.A., Muluk, H., Newcombe, P., Piercy, F.P., Poerwandari, E.K., Suradijono, S.H.R., Eds.; Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group: Abingdon, UK, 2018; pp. 445–450. [Google Scholar]

- Sensales, G.; Baldner, C.; Areni, A. Gender issues in the Italian political domain. Are woman/man ministers evaluated as different in terms of effectiveness of their behavior? TPM Test. Psychom. Methodol. Appl. Psychol. 2020, 27, 185–205. [Google Scholar]

| NCC | IPT | Lead | Fol | L–F | EDU | Age | M (SD) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCC | (0.74) | 3.40 (0.62) | ||||||

| IPT | 0.206 *** | (0.93) | 3.15 (1.06) | |||||

| Lead | −0.011 | −0.108 * | — | 0.66 (1.45) | ||||

| Fol | 0.169 *** | 0.101 * | 0.475 *** | — | 0.66 (1.41) | |||

| L–F | −0.173 *** | −0.204 *** | 0.534 *** | −0.490 *** | — | 0.00 (1.47) | ||

| EDU | −0.042 | −0.026 | 0.001 | −0.004 | 0.005 | — | — | |

| Age | 0.090 | 0.007 | 0.014 | 0.167 *** | −0.103 ** | 0.183 *** | — | 27.40 (9.14) |

| Gender | 0.044 | 0.015 | 0.248 *** | 0.121 ** | 0.085 | −0.078 | −0.134 ** | — |

| 95% Confidence Intervals | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dep | Pred | b | SE | Lower | Upper | t | p |

| IPT | Gender | 0.007 | 0.098 | −0.185 | 0.199 | 0.071 | 0.943 |

| IPT | Age | −0.001 | 0.005 | −0.011 | 0.009 | −0.168 | 0.867 |

| IPT | EDU | −0.029 | 0.083 | −0.197 | 0.134 | −0.345 | 0.730 |

| L–F | Gender | 0.249 | 0.133 | −0.012 | 0.509 | 1.868 | 0.062 |

| L–F | Age | −0.013 | 0.007 | −0.027 | 0.001 | −1.782 | 0.075 |

| L–F | EDU | 0.040 | 0.112 | −0.181 | 0.261 | 0.357 | 0.721 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Contu, F.; Albarello, F.; Pierro, A. Motivation to Avoid Uncertainty, Implicit Person Theories about the Malleability of Human Attributes and Attitudes toward Women as Leaders vs. Followers: A Mediational Analysis. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14010064

Contu F, Albarello F, Pierro A. Motivation to Avoid Uncertainty, Implicit Person Theories about the Malleability of Human Attributes and Attitudes toward Women as Leaders vs. Followers: A Mediational Analysis. Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 14(1):64. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14010064

Chicago/Turabian StyleContu, Federico, Flavia Albarello, and Antonio Pierro. 2024. "Motivation to Avoid Uncertainty, Implicit Person Theories about the Malleability of Human Attributes and Attitudes toward Women as Leaders vs. Followers: A Mediational Analysis" Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 1: 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14010064

APA StyleContu, F., Albarello, F., & Pierro, A. (2024). Motivation to Avoid Uncertainty, Implicit Person Theories about the Malleability of Human Attributes and Attitudes toward Women as Leaders vs. Followers: A Mediational Analysis. Behavioral Sciences, 14(1), 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14010064