Effects of Impulsivity and Interpersonal Problems on Adolescent Depression: A Cross-Lagged Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Impulsivity and Adolescent Depression

1.2. Interpersonal Problems and Adolescent Depression

1.3. Longitudinal Effects of Impulsivity and Interpersonal Problems on Adolescent Depression

1.4. Current Study

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Chinese Version of Barratt Impulsiveness Scale-11

2.2.2. Adolescent Self-Rating Life Events Check List

2.2.3. Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale

2.3. Collection and Analysis of Data

3. Result

3.1. Common Method Bias Analysis

3.2. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis

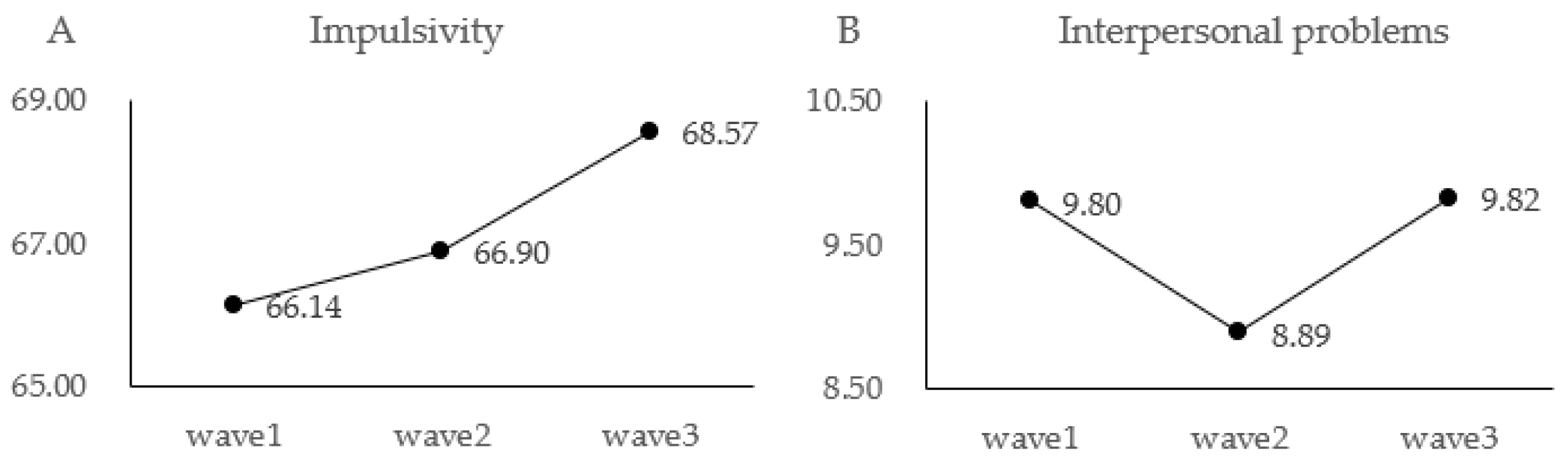

3.3. Changes in Impulsivity and Interpersonal Problems across the Three Measurements

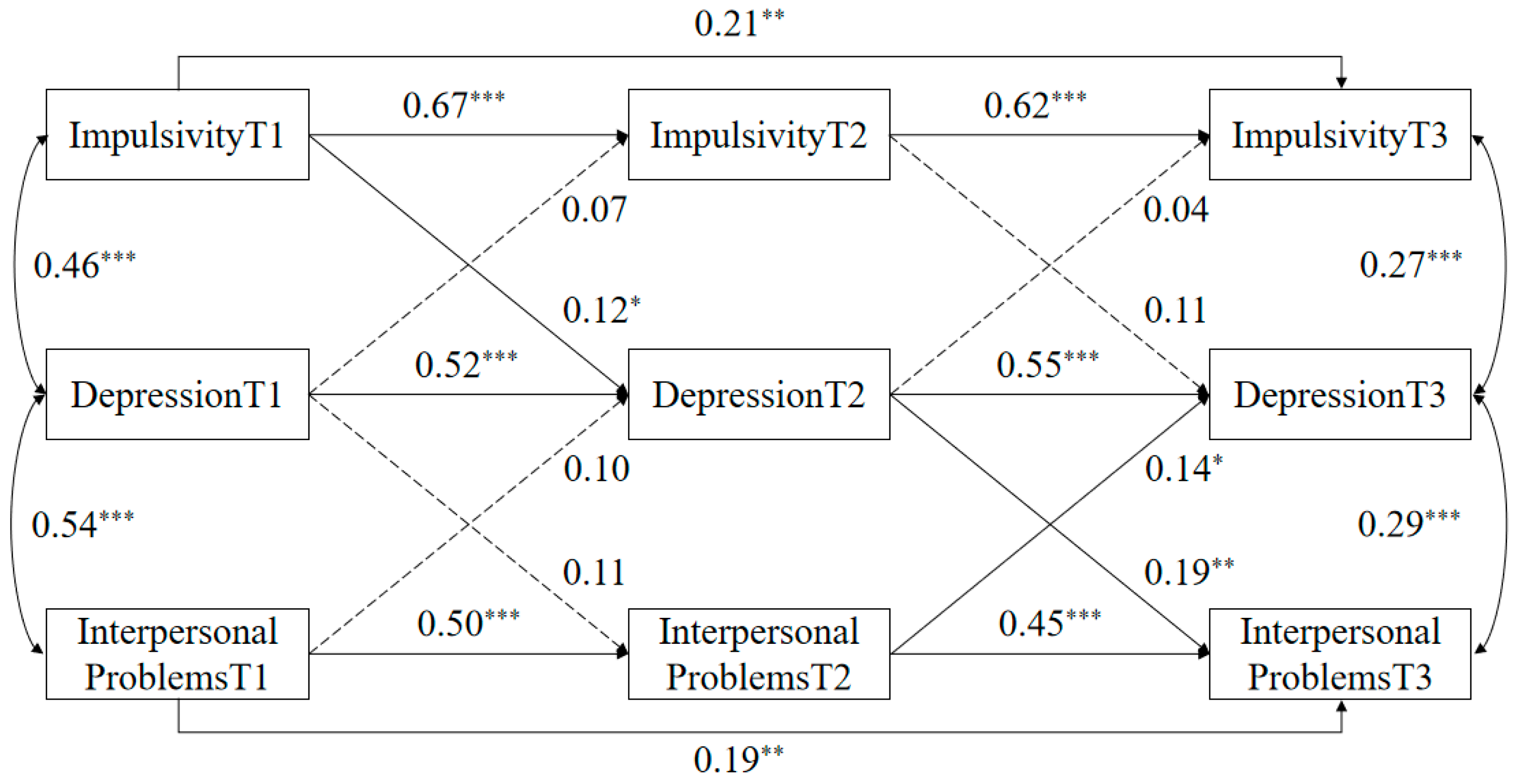

3.4. Cross-Lagged Analysis of Impulsivity, Interpersonal Problems, and Depression

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yang, D.; Wang, G.; Dong, Q. Depression and anxiety of secondary school students: Structure and development. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 2000, 16, 12–17. [Google Scholar]

- Thapar, A.; Eyre, O.; Patel, V.; Brent, D. Depression in young people. Lancet 2022, 20, 617–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- COVID-19 Mental Disorders Collaborators. Global prevalence and burden of depressive and anxiety disorders in 204 countries and territories in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet 2021, 398, 1700–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Merritt, D.H. Examining the association between parenting and childhood depression among Chinese children and adolescents: A systematic literature review. Child Youth Serv. Rev. 2018, 88, 316–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Song, X.; Shang, X.; Wu, M.; Sui, M.; Dong, Y.; Liu, X. A meta-analysis of detection rate of depression symptoms among middle school students. Chin. Ment. Health J. 2020, 34, 123–128. [Google Scholar]

- Bhatia, S.K.; Bhatia, S.C. Childhood and adolescent depression. Am. Fam. Physician 2007, 75, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Prager, L.M. Depression and suicide in children and adolescents. Pediatr. Rev. 2009, 30, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thapar, A.; Collishaw, S.; Pine, D.S.; Thapar, A.K. Depression in adolescence. Lancet 2012, 379, 1056–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monroe, S.M.; Simons, A.D. Diathesis-stress theories in the context of life stress research: Implicat-ions for the depressive disorders. Psychol. Bull. 1991, 110, 406–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moeller, F.G.; Barratt, E.S.; Dougherty, D.M.; Schmitz, J.M.; Swann, A.C. Psychiatric aspects of impulsivity. Am. J. Psychiatry 2001, 158, 1783–1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mobini, S.; Pearce, M.; Grant, A.; Mills, J.; RYeomans, M. The relationship between cognitive distortions, impulsivity, and sensation seeking in a non-clinical population sample. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 2006, 40, 1153–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, S.L.; Porter, P.A.; Modavi, K.; Dev, A.S.; Pearlstein, J.G.; Timpano, K.R. Emotion-related impulsivity predicts increased anxiety and depression during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Affect. Disord. 2022, 301, 289–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Li, S. Serial mediation of the relationship between impulsivity and suicidal ideation by depression and hopelessness in depressed patients. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fields, S.A.; Schueler, J.; Arthur, K.M.; Harris, B. The Role of Impulsivity in Major Depression: A Systematic Review. Curr. Behav. Neurosci. 2021, 8, 38–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piko, B.F.; Pinczés, T. Impulsivity, depression and aggression among adolescents. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 2014, 69, 33–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seroczynskia, A.D.; Bergemana, C.S.; Coccarob, E.F. Etiology of the impulsivity/aggression relationship: Genes or environment? Psychiatry Res. 1999, 86, 41–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luise, L.; Nina, H.; Nina, W.; Thomas, F.; Dajana, R.; Heide, G.; Lena, S. Daily impulsivity: Associations with suicidal ideation in unipolar depressive psychiatric inpatients. Psychiatry Res. 2022, 308, 114357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinberg, L.; Albert, D.; Cauffman, E.; Banich, M.; Graham, S.; Woolard, J. Age differences in sensation seeking and impulsivity as indexed by behavior and self-report: Evidence for a dual systems model. Dev. Psychol. 2008, 44, 1764–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Zh, X.; He, H. Developmental characteristics of adolescent sensation seeking, impulsivity. Ment. Health Educ. Prim. Second. Sch. 2018, 16, 20–24. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, S.; Han, M.; Zhang, M. The impact of interpersonal relationship on social responsibility. Acta Psychol. Sin. 2016, 48, 578–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Yan, Z.; Tang, W.; Yang, F.; Xie, X.; He, J. Mobile phone addiction levels and negative emotions among Chinese young adults: The mediating role of interpersonal problems. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 55, 856–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.M. What makes adolescents psychologically distressed? Life events as risk factors for depression and suicide. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2021, 30, 359–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meisel, S.N.; Colder, C.R. An examination of the joint effects of adolescent interpersonal styles and parenting styles on substance use. Dev. Psychopathol. 2022, 34, 1125–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delgado, E.; Serna, C.; Martínez, I.; Cruise, E. Parental Attachment and Peer Relationships in Adolescence: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scardera, S.; Perret, L.C.; Ouellet-Morin, I.; Gariépy, G.; Juster, R.P.; Boivin, M.; Turecki, G.; Tremblay, R.E.; Côté, S.; Geoffroy, M.C. Association of social support during adolescence with depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation in young adults. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e2027491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Li, J.; Jia RWang, Y.; Qian, S.; Xu, Y. Mental health problems and associated school interpersonal relationships among adolescents in China: A cross-sectional study. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2020, 14, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patterson, G.R.; Capaldi, D.M. A mediational model for boys’ depressed mood. In Risk and Protective Factors in the Development of Psychopathology; Rolf, J., Masten, A.S., Cicchetti, D., Nüchterlein, K.H., Weintraub, S., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990; pp. 141–163. [Google Scholar]

- Besharat, M.A.; Jafari, F.; Lavasani, M.G.A. Predicting symptoms of anxiety and depression based on interpersonal problems. Rooyesh-e Ravanshenasi J. 2021, 10, 35–44. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, X.; Zhang, K.; Chen, X.; Chen, Z. Report on National Mental Health Development in China (2019–2020); Social Sciences Academic Press: Beijing, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Fuligni, A.J.; Eccles, J.S.; Barber, B.L.; Clements, P. Early adolescent peer orientation and adjustment during high school. Dev. Psychol. 2001, 37, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wo, J.; Lin, C.; Ma, H.; Li, F. A study on the development characteristics of adolescents’ interpersonal relations. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 2001, 3, 9–15. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner, U.; Ceci, S.J. Nature-nurture reconceptualized in developmental perspective: A bioecological model. Psychol. Rev. 1994, 101, 568–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barratt, E.S.; Patton, J.H. Impulsivity: Cognitive, behavioral, and psychophysiological correlates. In Biological Bases of Sensation-Seeking, Impulsivity, and Anxiety; Zuckerman, M., Ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1983; pp. 77–116. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, L.; Xiao, S.; He, X.; Li, J.; Liu, H. Reliability and validity of Chinese version of Barratt Impulsiveness Scale-11. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 2006, 14, 343–344. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.C.; Liu, L.Q.; Yang, J.; Chai, F.X.; Wang, A.Z.; Sun, L.M. Development and psychometric reliability and validity of adolescent self-rating life events checklist. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 1997, 5, 34–36. [Google Scholar]

- Radloff, L.S. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl. Psych. Meas. 1977, 1, 385–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Yang, X.; Li, X. Psychometric features of CES-D in Chinese adolescents. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 2009, 17, 443–445. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald, R.P.; Ho, M.-H.R. Principles and Practice in Reporting Structural Equation Analyses. Psychol. Methods 2002, 7, 64–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, H.H.; Lundahl, L.H.; Lister, J.J.; Woodcock, E.A.; Greenwald, M.K. Mediational pathways among trait impulsivity, heroin-use consequences, and current mood state. Addict. Res. Theory 2018, 26, 421–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiber, L.R.N.; Grant, J.E.; Odlaug, B.L. Emotion regulation and impulsivity in young adults. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2012, 46, 651–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starosta, J.; Izydorczyk, B.; Sitnik-Warchulska, K.; Lizińczyk, S. Impulsivity and Difficulties in Emotional Regulation as Predictors of Binge-Watching Behaviours. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 743870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bos, E.H.; Bouhuys, A.L.; Geerts, E.; Van Os, T.W.D.P.; Van der Spoel, I.D.; Brouwer, W.H.; Ormel, J. Cognitive, physiological, and personality correlates of recurrence of depression. J. Affect. Disord. 2005, 87, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compare, A.; Zarbo, C.; Shonin, E.; Van Gordon, W.; Marconi, C. Emotional Regulation and Depression: A Potential Mediator between Heart and Mind. Cardiovasc. Psychiatry Neurol. 2014, 2014, 324374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dvorak, R.D.; Lamis, D.A.; Malone, P.S. Alcohol use, depressive symptoms, and impulsivity as risk factors for suicide proneness among college students. J. Affect. Disord. 2013, 149, 326–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harden, K.P.; Tuckerdrob, E.M. Individual differences in the development of sensation seeking and impulsivity during adolescence: Further evidence for a dual systems model. Dev. Psychol. 2011, 47, 739–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorilli, C.; Grimaldi Capitello, T.; Barni, D.; Buonomo, I.; Gentile, S. Predicting Adolescent Depression: The Interrelated Roles of Self-Esteem and Interpersonal Stressors. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J. Forging the Future Between Two Different Worlds: Recent Chinese Immigrant Adolescents Tell Their Cross-Cultural Experiences. J. Adolesc. Res. 2009, 24, 477–504. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, C.C.; Chan, S.M.; Cheng, F.F.; Sung, R.Y.; Hau, K. Are physical activity and academic performance compatible? Academic achievement, conduct, physical activity and self-esteem of Hong Kong Chinese primary school children. Educ. Stud. 2006, 32, 331–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hankin, B.L.; Mermelstein, R.; Roesch, L. Sex differences in adolescent depression: Stress exposure and reactivity models. Child Dev. 2007, 78, 279–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Demographic Characteristic | n | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Family type | Nuclear family | 157 | 74.41 |

| Extended family | 40 | 18.96 | |

| Not living with parents | 6 | 2.84 | |

| Single parent family | 8 | 3.79 | |

| Only child | Yes | 65 | 30.81 |

| No | 145 | 68.72 | |

| Missing | 1 | 0.47 | |

| Family location | City | 77 | 36.49 |

| County | 25 | 11.85 | |

| Town | 100 | 47.39 | |

| Village | 6 | 2.84 | |

| Missing | 3 | 1.42 | |

| Family income | Very high | 1 | 0.47 |

| Relatively high | 43 | 20.38 | |

| Average | 144 | 68.25 | |

| Relatively low | 3 | 1.42 | |

| Very low | 0 | 0.00 | |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Impulsivity T1 | — | ||||||||

| 2 Impulsivity T2 | 0.70 *** | — | |||||||

| 3 Impulsivity T3 | 0.66 *** | 0.78 *** | — | ||||||

| 4 Interpersonal Problems T1 | 0.31 *** | 0.30 *** | 0.24 *** | — | |||||

| 5 Interpersonal Problems T2 | 0.27 *** | 0.30 *** | 0.23 ** | 0.56 *** | — | ||||

| 6 Interpersonal Problems T3 | 0.28 *** | 0.29 *** | 0.33 *** | 0.52 *** | 0.63 *** | — | |||

| 7 Depression T1 | 0.46 *** | 0.38 *** | 0.35 *** | 0.54 *** | 0.37 *** | 0.38 *** | — | ||

| 8 Depression T2 | 0.39 *** | 0.47 *** | 0.41 *** | 0.43 *** | 0.50 *** | 0.48 *** | 0.63 *** | — | |

| 9 Depression T3 | 0.33 *** | 0.41 *** | 0.46 *** | 0.40 *** | 0.42 *** | 0.54 *** | 0.52 *** | 0.66 *** | — |

| M | 66.14 | 66.90 | 68.57 | 9.80 | 8.89 | 9.82 | 15.16 | 16.26 | 15.58 |

| SD | 13.50 | 13.05 | 12.59 | 6.28 | 6.54 | 6.65 | 10.59 | 9.76 | 10.16 |

| Model | χ2/df | CFI | RMSEA | SRMR | Δχ2 | Δdf | Correction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1 | 89.67/25 | 0.91 | 0.11 | 0.13 | — | — | 1.13 |

| M2 | 71.36/21 | 0.93 | 0.11 | 0.10 | 18.48 ** | 4 | 1.14 |

| M3 | 56.72/17 | 0.95 | 0.11 | 0.06 | 14.58 ** | 4 | 1.12 |

| M4 | 37.50/15 | 0.97 | 0.08 | 0.05 | 17.84 *** | 2 | 1.11 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, Y.; Tian, M.; Liu, Y.; Qiu, S.; Hu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Wang, C.; Xu, Z.; Lin, L. Effects of Impulsivity and Interpersonal Problems on Adolescent Depression: A Cross-Lagged Study. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14010052

Yang Y, Tian M, Liu Y, Qiu S, Hu Y, Yang Y, Wang C, Xu Z, Lin L. Effects of Impulsivity and Interpersonal Problems on Adolescent Depression: A Cross-Lagged Study. Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 14(1):52. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14010052

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Yanan, Mingyangjia Tian, Yu Liu, Shaojie Qiu, Yuan Hu, Yang Yang, Chenxu Wang, Zhansheng Xu, and Lin Lin. 2024. "Effects of Impulsivity and Interpersonal Problems on Adolescent Depression: A Cross-Lagged Study" Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 1: 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14010052

APA StyleYang, Y., Tian, M., Liu, Y., Qiu, S., Hu, Y., Yang, Y., Wang, C., Xu, Z., & Lin, L. (2024). Effects of Impulsivity and Interpersonal Problems on Adolescent Depression: A Cross-Lagged Study. Behavioral Sciences, 14(1), 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14010052