1. Introduction

Intrusive, ego-dystonic mental thoughts or images are common experiences for most of us [

1]. When, however, more and more mental energy and time are consumed in removing them from the awareness level through various mental or behavioral compulsions, the person reaches the clinical cutoff for obsessive compulsive symptoms, a disorder that affects a significant proportion of the population [

2,

3].

Obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), characterized by the presence of obsessive thoughts/images perceived as egodystonic and compulsions designed to reduce the immediate discomfort they produce (American Psychiatric Association, 2013), affects a significant proportion of the population [

2,

3]. Although both obsessions and compulsions are qualitatively common for most people [

1], a proportion of us end up suffering from obsessive compulsive spectrum disorders, the frequency of occurrence being the key factor that makes the difference in the transition to pathology. There is a consistent body of empirical evidence for the presence of excessive blame and guilt among the clinical population as opposed to the non-clinical [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]. Also, a number of experimental studies have concluded that the escalation of the two has the effect of increasing OCD-like behaviors in the non-clinical population [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13], and other neuroimaging studies [

14,

15] have revealed an overlap between brain areas involved in guilt processing and those affected by OCD.

Mancini [

1] proposed a refinement of the concept of guilt distinguishing between deontological and altruistic guilt. The former implies the violation of a rule in the person’s value system, and the latter the necessary existence of a victim [

1,

16,

17]. The cognitive model of obsessive disorders proposed by Mancini [

1] finds as its central assumption that the primary goal of OCD sufferers is to prevent deontological guilt, and a potential failure to achieve this goal “is perceived as an unacceptable and unbearable catastrophe” [

1] (p. 51). Apart from this, the model includes two other important goals of OCD sufferers, namely the neutralization of disgust and the feeling of “not just right experience” (NJRE)—the result of a mismatch between perception and reference schema, which can be felt at the level of all analyzers [

18]. Thus, an event (trigger) is interpreted by the subject as a threat, depending on the first evaluation (contamination/NJRE or the possibility of being guilty in the deontological sense). The interpretation leads to Attempted Solution 1—a complex, automatic reaction composed of emotions (anxiety, disgust, fear of guilt), specific cognitive processes (selective attention and memory), and observable or mental behaviors (compulsions). This reaction, over time, has a paradoxical effect—it leads to generalization (trigger situations occur more often, confirm the belief about the threat, lead to a greater investment of time and energy in attempts to resolve it, and thus increase the value of the threatened goal). Meta-evaluation comes next, or second-order evaluation, usually self-derogatory and critical of the first-order evaluation and solution attempt [

1].

The Schema Therapy (ST) model defines early maladaptive schemas as dysfunctional ways of organizing information about the self and others, consisting of memories, emotions, cognitions, and bodily sensations, developed as a result of repeated experiences of frustration with basic emotional needs in childhood and adolescence [

19]. The concept of the schema mode refers to a specific mental state that arises from the activation of one or more schemas. There are several types of modes that describe the intrapsychic dynamics of the person: child modes (parts that express unaddressed needs: Vulnerable child—lonely, guilty, abused, neglected, sad—Angry child, Impulsive child), dysfunctional parent modes (parts that represent introjected parental messages—Punitive Parent, Demanding Parent), and specific coping modes (Surrender modes—compliant, less assertive—Detached/Avoidant modes, Overcompensation modes) [

20,

21]. In terms of early maladaptive schemas, there does not seem to be a specificity of OCD sufferers, as they report higher scores compared to other pathologies across a range of maladaptive schemas including Dependence/Incompetence, Vulnerability to hazards, Abandonment, Social Isolation, Emotional Deprivation, Entitlement, Subjugate, Search for validation, Negativity/Pessimism, and Unrealistic Standards [

22,

23,

24,

25,

26]. In terms of schema modes, however, a number of studies have identified a specific organization of obsessive functioning that includes Vulnerable child mode (fearful and guilty), Angry child mode, Punitive Parent mode, Demanding Parent mode, Perfectionist Over-controller mode, and Detached Self-soother mode [

25,

26,

27,

28,

29]. Some research [

20] has attempted to integrate the two cognitive models into a common conceptualization with the aim of developing more effective therapeutic interventions for OCD sufferers. Building on these theoretical attempts, we set out to empirically test a moderated mediation model based on these two representations.

Consistent with the review of the two cognitive models as well as the common conceptualization of OCD proposed by Tenore [

20], the main objective of the present study is to examine, in a non-clinical population, the validity of an integrated, moderated mediation explanatory model for obsessive-like psychological functioning. Our hypothesis builds on previous attempts in the literature [

20] (pp. 2278–2295) to bring together the two cognitive models, namely the Mancini model and the ST model, into a common conceptualization, summarized in the

Figure 1 exemplified below:

The new aspect of our article is that it differentiates between the role of the demanding parent (who imposes unrealistic rules and standards) and the critical and punitive parent (who punishes) in maintaining obsessive mental dynamics.

Thus, we propose as the first Hypothesis (1) that fear of guilt, disgust tendency and sensitivity, as well as NJRE severity mediate the effect of the Demanding Parent mode on the level of OCD-like tendencies, and the second Hypothesis (2) is that this mediation is moderated by the Punitive Parent mode.

3. Results

We tested the internal consistency of the scales used in our study by calculating Cronbach’s α-coefficient. For Young’s Modes Questionnaire-form SMI-2, the internal consistency coefficients α-Cronbach were calculated for each subscale and were 0.78 (Punitive Parent) and 0.80 (Demanding Parent). The Padua Inventory of Obsessive-Compulsive Symptoms for our sample had an internal consistency coefficient α-Cronbach equal to 0.94. For the Fear of Guilt Scale for OCD, the internal consistency coefficient Cronbach’s α was 0.87. The Cronbach’s α internal consistency coefficients were calculated on each subscale for the Disgust Propensity and Sensitivity Scale-Revised and were 0.86 (disgust proneness) and 0.86 (disgust sensitivity), and for the total scale, the coefficient was 0.91. For the Not Just Right Experiences Questionnaire-Revised, we obtained an internal consistency coefficient α-Cronbach equal to 0.92.

The normality assumption did not meet the distribution of all variables, which is why we used a bootstrap approach for data analysis [

39]. All the information can be found in

Table 2.

To test the first Hypothesis (1) of our study, that fear of guilt, tendency and sensitivity to disgust, together with NJRE severity mediate the effect of the Demanding Parent mode on the level of OCD tendencies, we used PROCESS (model 4) proposed by Hayes [

38] (

Figure 2).

The results show that the Demanding Parent mode predicts fear of guilt (b = 0.94, t(203) = 8.13, p < 0.001). Also, the Demanding Parent mode is a significant predictor of disgust tendency and sensitivity (b = 0.43, t(203) = 4.63, p < 0.001) and NJRE severity (b = 0.52, t(203) = 6.47, p < 0.001).

In turn, the three mediators are significant predictors of OCD-like tendencies. Thus, fear of guilt predicts obsessive tendencies (b = 0.19, t(200) = 2.40, p = 0.01); tendency and sensitivity to disgust is also a significant predictor of OCD-like tendencies (b = 0.76, t(200) = 7.44, p < 0.001), as is NJRE severity (b = 0.77, t(200) = 6.41, p < 0.001).

The overall effect of the Demanding Parent mode on OCD-like tendencies is positive and significant (b = 1.06, t(203) = 6.13,

p < 0.001) (

Table 2). There is no direct, significant effect of the Demanding Parent mode on obsessive tendencies (b = 0.14, t(200) = 1.00,

p = 0.31), implying that the mediation is total. The results, summarized in

Table 3, indicate that our hypothesis is confirmed, such that fear of guilt mediates the effect of the Demanding Parent mode on OCD-like tendencies (indirect effect = 0.18, SE = 0.09, 95% CI (0.0061; 0.3712)—CI does not include 0), along with disgust tendency and sensitivity (indirect effect = 0.33, SE = 0.08, 95% CI (0.1830; 0.5178)—CI does not include 0) and NJRE severity (indirect effect = 0.40, SE = 0.09, 95% CI (0.2315; 0.5958)—CI does not include 0).

We can therefore conclude from the results that there is a statistically significant indirect effect of the Demanding Parent mode on OCD-like tendencies, and that it is mediated entirely by fear of guilt, tendency and sensitivity to disgust, and NJRE severity.

To test Hypothesis (2) of the present study, that the mediation of the effect of the Demanding Parent mode on OCD tendencies by the fear of guilt tendency and sensitivity to disgust and NJRE severity is moderated by the Punitive Parent mode, we used PROCESS (model 14) proposed by Hayes [

38] (

Figure 3).

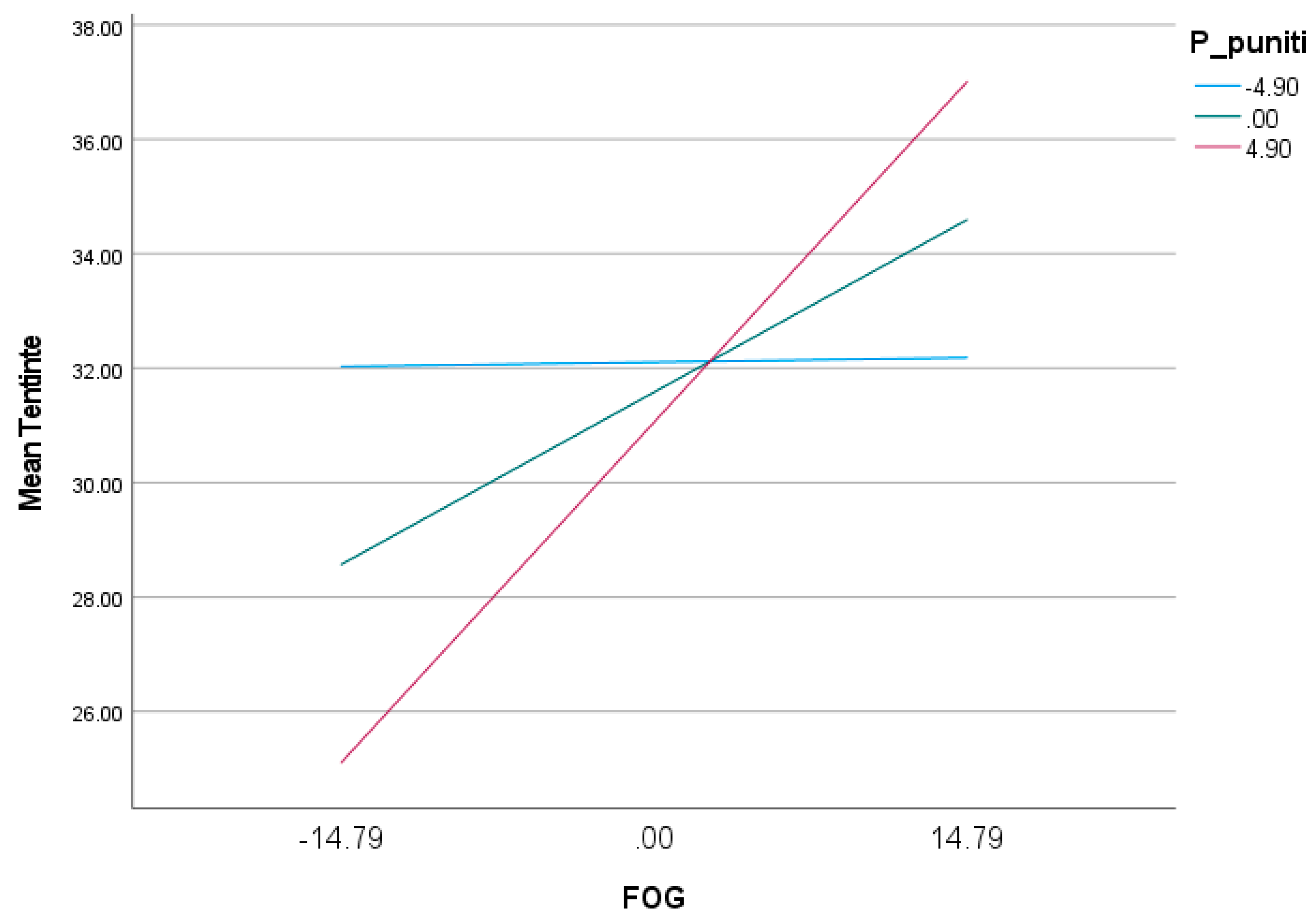

The results show that the Punitive Parent mode significantly moderates only the effect of fear of guilt on OCD-like tendencies (βsimple = 0.04, SE = 0.01,

p = 0.01, 95% CI (0.0086; 0.0724)—CI does not include 0), not the effect of disgust tendency and sensitivity or NJRE severity on obsessive tendencies (

Table 4).

At low Punitive Parent mode scores (one standard deviation below the mean), the effect of fear of guilt on OCD-like tendencies is positive but statistically insignificant (b = 0.005, SE = 0.10,

p = 0.96, 95% CI (−0.2023; 0.2124)—CI includes 0). In contrast, as Punitive Parent mode scores increase, the effect of fear of guilt on obsessive tendencies also increases and becomes significant. Thus, at high Punitive Parent mode scores (one standard deviation above the mean), the effect of fear of guilt on OCD-like tendencies is positive and statistically significant (b = 0.40, SE = 0.12,

p = 0.001, 95% CI (0.1575; 0.6473)—CI does not include 0) (

Table 5;

Figure 4).

The Punitive Parent mode does not significantly moderate the effect of disgust tendency and sensitivity on obsessive tendencies (

Table 4,

Figure 5).

Also, the Punitive Parent mode does not significantly moderate the effect of NJRE severity on OCD-like tendencies (

Table 4,

Figure 6).

The bootstrap results also show a significant moderated mediation effect in which the Punitive Parent mode moderates the indirect effect of the Demanding Parent mode on obsessive tendencies, mediated by fear of guilt. Thus, at low values of the Punitive Parent mode (one standard deviation below the mean), the indirect effect of the Demanding Parent mode on OCD-like tendencies mediated by fear of guilt is positive but statistically insignificant (ind effect = −0.004, SE = 0.10, 95% CI (−0.2077; 0.2156)—CI includes 0). At high moderator values (one standard deviation above the mean), the indirect effect of the Demanding Parent mode on obsessive tendencies, mediated by fear of guilt, increases and becomes statistically significant (ind effect = 0.37, SE = 0.12, 95% CI (0.1162; 0.6169)—CI does not include 0) (

Table 6).

The Punitive Parent mode does not moderate the indirect effect of the Demanding Parent mode on OCD-like tendencies mediated by disgust tendency and sensitivity. The effect tends to decrease with increasing Punitive Parent mode, but not significantly (

Table 7).

There is also no significant moderation on the indirect effect of the Demanding Parent mode on obsessive tendencies mediated by NJRE severity. In this case, we observe a trend of increasing indirect effect as Punitive Parent mode values increase, but this is not statistically significant (

Table 8).

We can therefore conclude that the second hypothesis of our study is only partially confirmed, in the sense that the Punitive Parent mode moderates only the indirect effect of the Demanding Parent mode mediated by fear of guilt, not the indirect effect mediated by the tendency and sensitivity to disgust and the severity of NJRE. Moreover, the results of the analysis show that the indirect effect of the Demanding Parent mode on obsessive tendencies mediated by fear of guilt is significant only at medium and high values of the Punitive Parent mode, not at low values of the moderator.

4. Discussion

The objective of the present study was to propose and examine, in a non-clinical population, the validity of an integrated, moderated mediation model for obsessive mental functioning based on cognitive theories [

1,

25] and previous research that proposed a common conceptualization model [

20].

The two hypotheses, formulated in line with this objective, were as follows: (1) fear of guilt, tendency and sensitivity to disgust, as well as NJRE severity mediate the effect of the Demanding Parent mode on the level of OCD-like tendencies; and (2) this mediation is moderated by the Punitive Parent mode.

The results revealed that there is a significant positive, indirect effect of the Demanding Parent mode on OCD-like tendencies and this is fully mediated by fear of guilt, tendency and sensitivity to disgust, and NJRE severity, thus supporting our first hypothesis. Fear of guilt corresponds to the concept of deontological guilt described by Mancini, in which the individual is excessively concerned with the particular mode of conduct and not necessarily with the negative outcome itself [

1,

34]. We can therefore conclude that, in line with previous research, a demanding and critical home environment [

40,

41], which induces guilt [

42] or is characterized by parental control and criticism, high expectations, pressure toward unrealistic standards [

43,

44], and leads to the introjection of a demanding parental figure, i.e., the Demanding Parent mode [

32], has an indirect effect on obsessive tendencies. The more demanding the internal dialogue, the greater the fear of guilt, the tendency and sensitivity to disgust, and the severity of the NJRE. And the higher these are, as supported by the model proposed by Mancini [

1], the higher the increase in intensity of OCD-like symptomatology.

As for the second hypothesis of our study, it was only partially confirmed. Consequently, in view of previous research proposing the integration of the Schema Therapy Modes model with the Mancini model [

20,

45], as well as the data obtained in the first part of this study, we proposed and analyzed an integrated explanatory model of moderated mediation. Thus, we wanted to test whether the indirect effect of the Demanding Parent mode on OCD-like tendencies, mediated by fear of guilt, tendency and sensitivity to disgust, together with NJRE severity, is moderated by the Punitive Parent mode. The results suggest that there is moderate mediation only in the case of the guilt–fear-mediated relationship. Furthermore, from the data, we can state that the indirect effect of the Demanding Parent mode on obsessive tendencies is mediated by fear of guilt only in the case of medium and high values (one standard deviation from the mean) of the Punitive Parent mode; in the case of low values of this mode (one standard deviation below the mean), the indirect effect mediated by fear of guilt remains positive but is insignificant. In the case of the indirect effect of the Demanding Parent mode on OCD-like tendencies mediated by disgust tendency and sensitivity as well as NJRE severity, there is no moderated mediation by the Punitive Parent mode. The results are in agreement with previous research that argues that a Punitive Parent mode that results in a very low tolerance for fault, i.e., withdrawal of affect, ignoring the child, and thus threatening the loss of the meaningful relationship [

46,

47], causes guilt-experiencing, which should be avoided at all costs. In other words, if the demanding internal dialogue, with unrealistic standards and over-responsibility, characteristic of the Demanding Parent mode, (e.g., “I must do everything perfectly”/“I cannot afford to be wrong”) is coupled with a punitive, unforgiving internal dialogue, characteristic of the Punitive Parent mode (“I am a bad person”/“I do not deserve compassion”/“I deserve to be punished”, etc.), the level of obsessive-like symptoms grows significantly by increasing the level of fear of guilt.

The results indicate that the internalization of a demanding internal dialogue, centered on excessive rules and unrealistic standards, resulting from a strict parental style, excessively centered on morality, only partially explains the development of an obsessive mental functioning. What moderates the effect of such an environment and can favor the development of an OCD pathology is the consequence of deviating from rules and standards. If this consequence is applied to the child in the form of harsh criticism and punishment, internalized in the form of an internal self-critical and self-punishing dialogue, the risk of developing an obsessive compulsive pathology increases significantly. The tested model is different from other mediation models because it starts from the common conceptualization of the two cognitive models. Other models do not take into account the role of internal dialogue in the severity and maintenance of this pathology.

The results have some clinical implications, as they support previous results of experimental research [

45,

48,

49] that a direct therapeutic intervention on demanding and punitive internal dialogue and, thus, on the Demanding Parent mode and Punitive Parent mode can lead to a decrease in OCD symptoms as well as to the long-term maintenance of the results achieved by the classical CBT intervention protocol, which exclusively targets fear of guilt, disgust proneness and sensitivity, or NJRE severity (hence mediators), in obsessive patients.

As limitations of our study, we mention mainly the impossibility of generalizing conclusions, given that our study group is not a representative sample of the non-clinical population. Also, the fact that the research group was predominantly female may have influenced the results. This limitation can be remedied by replicating this study on a more homogeneous group. It is also possible that other confounding variables that have not been controlled may influence our conclusions, such as potential personality disorders of subjects frequently associated with obsessive compulsive disorder-avoidant, dependent, borderline, obsessive compulsive, passive-aggressive, histrionic personality disorder [

31].

We therefore believe that future research would be needed to verify our proposed mediation and moderated mediation models. Also, further research might consider testing the validity of the model on a more balanced sample and taking into account other confounding variables such as possible strong personality tendencies.