1. Introduction

In a knowledge-based economy, companies pay more attention to knowledge management [

1]. The company’s knowledge base is the source of sustainable innovation and the basis for gaining a competitive advantage [

2]. The knowledge embedded inside employees is the most original form of company knowledge, and whether the knowledge of employees can be transformed into company knowledge depends on employees’ knowledge sharing [

3]. Defined as the willingness and behavior of individuals in an organization to share with others the knowledge they have acquired or created [

4], knowledge sharing is an indispensable premise contributing to team creativity and organizational innovation in a flexible work context [

5,

6].

Previous studies have suggested that individual factors, such as values [

7,

8], commitments [

9], personality traits [

10], motivations [

11,

12], and team-level factors, such as interpersonal trust [

13] and team cohesiveness [

14,

15], are effective in fostering knowledge sharing in organizations. Moreover, recent evidence indicates that companies’ supportive policies and arrangements facilitate knowledge sharing among employees [

16] because they shape their daily work characteristics and determine their work statuses, providing substantial support for their knowledge sharing [

17,

18]. Accompanying the ongoing outbreaks of COVID-19 in the post-epidemic context, many employees frequently telecommute beyond their companies and adopt flexible schedules to balance their work tasks. Flexible work arrangements (FWAs) have become a popular human resource management policy in practice [

19,

20,

21]. The use of FWAs has significantly changed the conditions for knowledge sharing among employees [

22]. However, insufficient research has considered the effects of widely implicated FWAs on knowledge sharing.

FWAs emerged as early as the 1980s, covering forms of flexi-time and flexi-locations, and were initially designed as organizations’ supportive policies for their employees [

23]. Some scholars, from the theoretical perspective of social exchange, have argued that FWAs could generate a wide range of functional outcomes [

24], such as promoting employees’ affective commitment [

25,

26] and work satisfaction [

27,

28], decreasing their quitting intentions toward organizations [

29]. However, a small body of research is revisiting the view that FWAs help organizations and employees obtain optimistic outcomes. As Weeks (2011) suggests, FWAs may seem like friendly, supportive plans, but actually, employees rarely benefit from these flexible practices because they are burdened with more work pressure in family life and suffer from a higher work–family imbalance [

30]. Some scholars also indicate that FWAs inevitably heighten the intensity and strain of work tasks [

31,

32], which would undermine employees’ work efforts in the long run [

33] and be detrimental to employees’ long-term work goals [

34].

Besides the psychological stress and work–family conflicts, recent evidence shows that using FWAs may stimulate unpleasant affective responses among employees [

34] because the use of FWAs is embedded in employees’ daily work routines and would shape the events of work, which would shock the regularity of employees’ affect patterns and elicit affective responses [

35]. The effects of FWAs regarding affective aspects have been largely overlooked. Moreover, the work events shaped by FWAs include changes in work schedules and locations and stimulate changes in work-related interactions between individuals [

21,

36]. Despite current studies’ attention to the potential hazards of FWAs, this research primarily focuses on the intrapersonal outcomes of employees, and few studies exist regarding the interpersonal impacts of FWAs on employees. In this study, we will pay attention to the affective response triggered by FWAs.

Workplace loneliness reflects the employees’ psychological and affective experience of low-quality interpersonal relationships and unsatisfied affective needs in workplace social interactions [

37,

38]. According to affective event theory, sparse interpersonal contact and geographic isolation events are proximal triggers of workplace loneliness [

35,

39]. To be more specific, flexi-time leads to employees’ irregular working time rhythms with supervisors and colleagues, while flexi-locations isolate employees geographically from their supervisors and colleagues [

25]. These work events and changes induced by FWAs’ usage impede the building of social connections between employees, which subsequently frustrates their affective affiliation. Therefore, we argue that using FWAs triggers employees’ workplace loneliness.

As Wright and Silard (2021) noted, workplace loneliness is a negative affective experience that constantly drains an individual’s psychological resources. The possible consequence for employees experiencing workplace loneliness is the avoidance of social engagement and interaction [

39]. In addition, individuals who feel lonely are more reluctant to engage in risky activities [

40]. However, knowledge sharing implies a transfer of ownership of knowledge, also embodied as a social activity covering at least two-party interactions [

4]. Accordingly, employees will likely reduce altruistic knowledge-sharing behaviors when they feel lonely.

Moreover, the effect of workplace events on individuals’ affective reactions and social intentions and behaviors depends upon contextual characteristics [

35]. In the FWA scenarios, employees are linked by various weak or strong task correlations to accomplish tasks together. Task interdependence refers to how employees depend on other team or organization members to carry out their work effectively [

41]. Previous evidence has shown that task interdependence would buffer the social side effects of work flexibility [

42] because it would change the interactions that influence the employees’ processes of interpreting events that occur in an organization [

43,

44]. Since task interdependence creates task-based connections for employees, we argue that task interdependence can mitigate the negative impacts of FWAs on employees’ workplace loneliness and knowledge sharing.

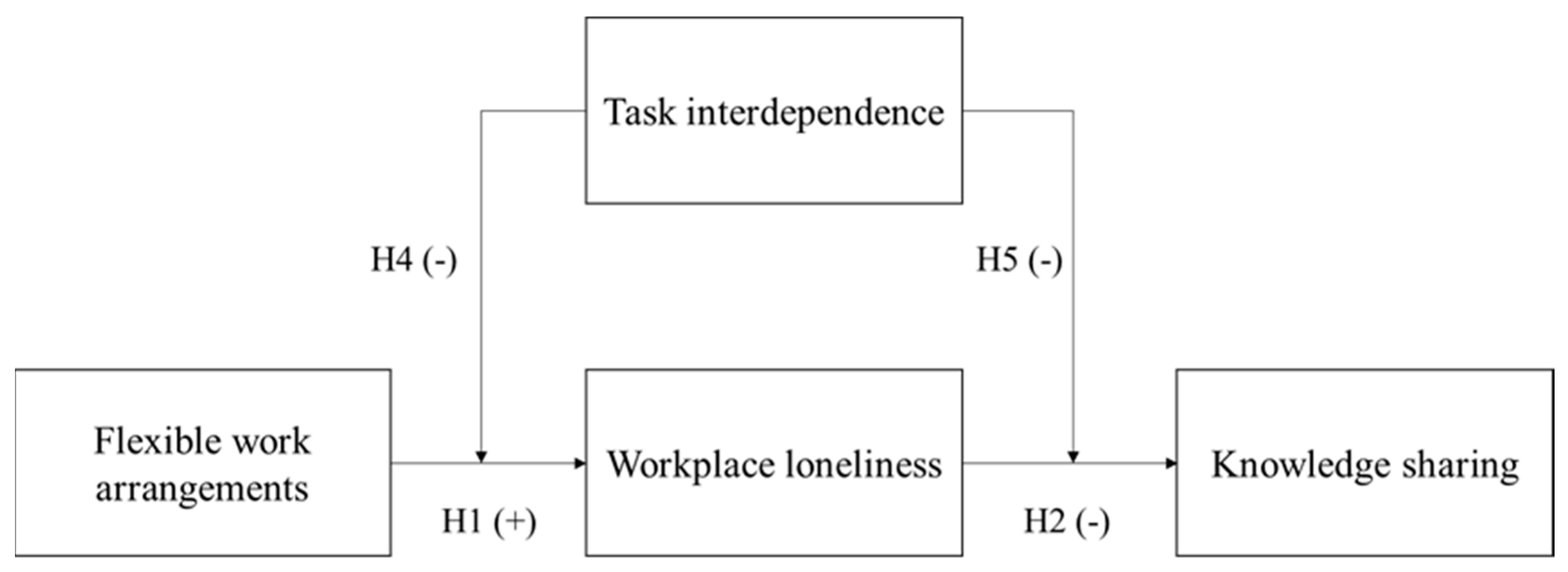

Based on affective events theory, we propose that adopting FWAs would promote employees’ affective experience of workplace loneliness, and employees who suffer from workplace loneliness are more reluctant to share their knowledge with colleagues. The dysfunctional effect of FWAs is constrained by the distinct job characteristic—task interdependence—which determines the mutual dependence of work assignments among employees under FWA scenarios [

45]. Employees who select FWAs will have more workplace loneliness psychological experiences when they face a lower level of task interdependence. Our theoretical model is presented in

Figure 1.

Our study makes theoretical contributions to the extant literature in several ways. First, we extended the literature on the passive effects of FWAs from an irrationally affective perspective. While previous research has discussed the impact of FWAs on individual work attitudes and behaviors based on rational perspectives such as the social exchange theory [

25], our study finds that affective experiences triggered by FWAs can also impact individual behaviors. We further support Spieler et al.’s (2017) argument that the chronic implementation of FWAs can negatively affect employees’ affective states [

34]. Second, we identified workplace loneliness as an affective mediating mechanism. Our study indicates that the widely implemented FWAs, especially in the post-epidemic period or a long time in the future, can stimulate employees’ perceived workplace loneliness due to the external work characteristics that employees are exposed to rather than employees’ personalities [

46,

47]. Third, we enriched the research on the employees’ knowledge-sharing preconditions. FWAs, as companies’ management practices, would change employees’ daily work status and further discourage the employees’ knowledge sharing. Fourth, our study clarifies task interdependence as a boundary condition to mitigate the dysfunctional effects of FWAs. Therefore, managers can alleviate the interpersonal concerns generated by FWAs by adjusting the interdependence of work tasks between subordinates.

5. Discussions

A web-based questionnaire survey (Study 1, N = 314) and a three-wave field survey (Study 2, N = 343) provided data for our theoretical model, and all proposed hypotheses were accepted.

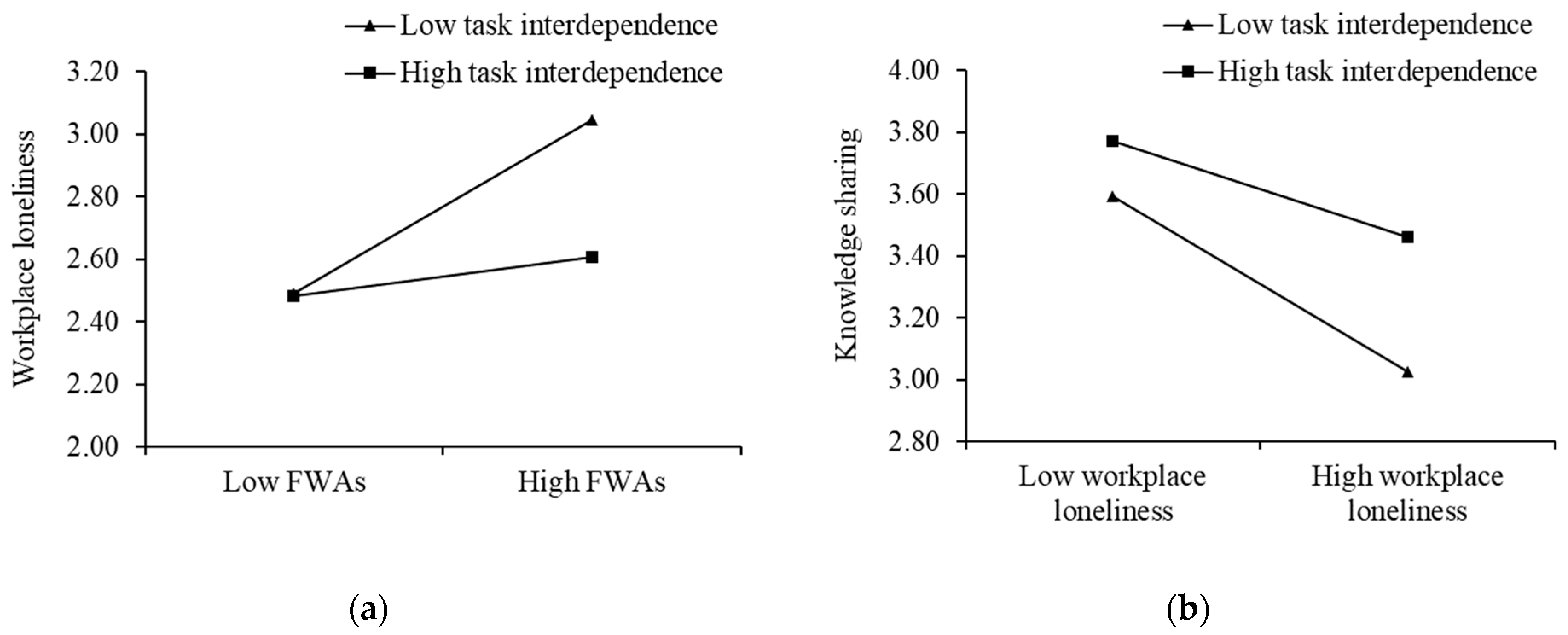

For Hypothesis 1, the results of our two studies suggest that the extensively implemented FWAs during the post-epidemic period triggered a negative affective experience of workplace loneliness among employees. Whether flexi-time or flexi-locations, these flexible work arrangements significantly interrupt employees’ daily work routines, provoking a range of affective events and changes for employees. For example, employees work with virtual devices through the screen and communicate with their supervisors and colleagues by email, telephone, and other electronic social media. They are distributed individually in different locations and adopt various office hours when they work. In the long run, these situations are not conducive to the establishment of social relationships and the satisfaction of belonging affective needs among employees.

For Hypothesis 2 and Hypothesis 3, our results indicate that workplace loneliness mediates the negative relationship between FWAs and employees’ knowledge sharing. The affective mechanism is a crucial mediating pathway through which FWAs’ usage influences employees’ interpersonal behaviors. Specifically, in flexible working scenarios, when employees feel the perceived absence of social relationships and deprivation of affective connections at work, they decrease their participation in altruistic social activities, which avoids the further depletion of psychological resources. Meanwhile, knowledge sharing also requires a high level of interpersonal trust and requires the sharer to take the risk of losing ownership of the knowledge. Individuals who feel lonely are less likely to trust others in their social activities and less willing to take additional risks for others.

For Hypothesis 4, Hypothesis 5, and Hypothesis 6, our results reveal that employees’ affective responses towards FWAs and the inhibitory effect of FWAs on knowledge sharing are moderated by task interdependence. Task interdependence, as an essential work characteristic, is widely embedded in the employee’s task scenarios and determines how employees complete their work tasks. Even in temporally inconsistent and spatially separated work conditions, task-based relationships between employees create opportunities for employees to build social relationships. Motivated by the collective task objective, employees frequently exchange information with colleagues, which facilitates building task-based trust among employees. Thus, a high degree of task interdependence would alleviate workplace loneliness due to FWAs and mitigate the tendency to reduce knowledge sharing due to unpleasant lonely experiences.

5.1. Theoretical Contributions

First, we extended the literature on the disruptive effects of FWAs from an irrationally affective perspective. Our findings revealed that FWAs did not always yield good consequences, although they were designed to improve employees’ performance. Earlier studies on FWAs were primarily based on rational perspectives, such as social exchange and resource conservation, which view FWAs as signals that companies value their employees’ needs or as resource supports to their employees and argue that FWAs can bring employees positive outcomes [

23,

28]. Our findings found that FWAs could trigger a sensual, psychological experience and create a negative affective reflection of workplace loneliness, which drain the individuals’ psychological resources and make them less likely to engage in altruistic behaviors. We also further support Spieler’s (2017) argument that FWAs are not simple company management practices: they also carry some liabilities in that long-term (chronic) implementation of FWAs can have detrimental outcomes on organizational outcomes [

34].

Second, we enriched the research on the employees’ knowledge-sharing preconditions. Although previous studies on the precursors of knowledge sharing have mainly been discussed from the individual level [

8,

11,

12,

45], our analysis takes an organizational level and found that FWAs as a company’s management policy impacted the employees’ knowledge sharing. While many scholars have pointed out that supportive company policies and practices promote the employees’ knowledge sharing [

56,

56,

83,

84], the results of our study show a different view: that FWAs as supportive company policies discourage the employees’ knowledge sharing. We argued that whether supportive company practices promote the employees’ knowledge sharing depends on the specific content of the policies and procedures and their particular impact on the employees’ daily work status.

Third, we developed workplace loneliness as an affective mediating mechanism from the perspective of the affective events theory. Our study responded to Wright and Silard’s (2021) call for attention to workplace loneliness [

39]. Even though employee feelings of loneliness are prevalent, attention to workplace loneliness in the HR field is limited [

38,

85] and previous literature on the factors impacting employee loneliness has primarily focused on the internal aspects of individuals and ignored the role of the external environment [

52]. Our study argued that the widely implemented FWAs, especially in the post-epidemic period, can lead to workplace loneliness, which is not due to employee personality traits [

47], but due to the external work environment and characteristics that employees are exposed to [

46]. This workplace loneliness will further negatively influence employees’ work attitudes and behaviors, damaging employee relationships in the long run and preventing regular communication and the exchange of work tasks [

37,

86].

Fourth, our study clarifies task interdependence as a boundary condition to mitigate the dysfunctional effects of FWAs. In the post-epidemic era, employee work paradigms have undergone disruptive changes [

87]. With FWAs becoming the dominant working style, these changes in work patterns may inevitably induce alienating reactions in the employees’ psychological experiences and behaviors [

88]. Shockley et al. (2021) suggested that task interdependence could amplify the positive relationship between employees’ communications (quality and frequency) and their performance, especially in the teleworking context [

89]. Chong et al. (2020) demonstrated that task interdependence could mitigate daily exhaustion caused by task setbacks due to employees working remotely during COVID-19 [

19]. Our study suggests that task interdependence can play a beneficial moderating role not only in the context of flexi-locations but also in the context of flexi-time.

5.2. Practical Implications

Our study confirmed that FWAs could impair employees’ knowledge sharing from an affective perspective. The results can enlighten managers to think critically about the design of FWAs. To reduce the harmful effects of FWAs, managers should pay more attention to the employees’ psychological needs and affective experiences and take measures to minimize the interpersonal disconnection between employees due to geographical isolation and time discontinuity.

For example, companies can hold more meetings to share activities and host more online group activities to enhance employee connections. Additionally, our research results show that higher task interdependence can weaken the adverse effects of FWAs. Therefore, when managers make task assignments for employees who adopt FWAs, they can assign tasks that require cooperation and coordination among colleagues and use the work tasks as a bridge to establish the connection between employees and increase the communication between them, thus enhancing the employees’ sense of belongingness and team task participation.

5.3. Limitations and Future Directions

First, although Study 2 adopted a three-wave research design to minimize common method bias, the data in Study 2 were reported by the same employees. Therefore, future studies can be improved in terms of method design. For example, the measurement of knowledge sharing can take the form of a combination of colleague and supervisor assessment, and the measurement of FWAs can use objective indicators.

Second, our study mainly discussed the impact of FWAs on the employees’ negative affective experience of workplace loneliness. However, the affective structure of individuals is characterized by complexity, multidimensionality, and instability [

90,

91]. Employees may have other affective responses in addition to workplace loneliness when facing the FWAs, and these different affective reactions may lead to distinct behavioral outcomes. Future studies could also explore the effects of FWAs on other affective experiences, such as anxiety and depression [

92,

93].

Finally, this study only discusses the moderating role that task interdependence plays in the harmful effects of FWAs. In addition to specific job characteristics, literature on affective events theory suggests that leadership and non-job factors (i.e., personal traits) may also play moderating roles in the relationship between FWAs and employees’ adverse affective reactions [

94,

95]. For example, supervisor support and the richness of the employees’ family life can help mitigate the negative affective experience with FWAs. These are all topics that can be discussed continuously in the future.