1. Introduction

Individuals face various challenges throughout their lives, and the source of these challenges may be individual problems, economic difficulties, work demands, natural disasters, diseases, or various other environmental factors [

1]. In the face of these challenges, some personality traits are considered to provide support, and psychological resilience is particularly cited in many studies as one of these personality traits. Individuals react differently to stressful situations they encounter throughout their lives. While some develop negative attitudes towards negative life events, others can develop positive attitudes and can adapt to these circumstances more easily. Psychological resilience is considered to play a significant role in people’s successful overcoming of these stressful life events [

2].

Human capital is the most important resource that enhances an organization’s competitiveness and effective functioning. Since people seek social belonging not only in their private lives but also in their work lives as members of an organization, they desire to be accepted by the other members of their work group [

3]. When they are not fully accepted by their work group, they are likely to have some negative experiences, such as social exclusion or ostracism. Williams [

4] defines ostracism as a person’s being ignored, isolated, and pushed out of the group without any justification by another individual or group. Leary, Koch, and Hechenbleikner [

5] stressed that ostracism is a serious problem since it is associated with a number of negative emotional states, such as sadness, loneliness, jealousy, guilt, shame, and social anxiety.

As teachers have a significant impact on the development and growth of children throughout their lives, they are also considered to have a crucial role in the development of societies [

6]. Therefore, teaching is one of the most important yet stressful professions. Teachers’ professional success usually depends on their determination to educate individuals in the best way possible [

6]. In order for teachers to show this determination, they need to be able to cope with the challenges they face, which particularly requires higher levels of psychological resilience because their psychological resilience can both protect them from and against psychological distress in the event of stressful or traumatic life events [

7]. As in every organization, teachers may also experience ostracism in their schools, which may result in several negative outcomes such as loneliness, alienation, stress, anxiety, aggression, being late for work, or absenteeism in the workplace [

8]. Hence, ostracism could lead to an increase in the risk of teacher burnout, as evidenced by some previous research [

9]. Burnout, which is a negative emotional state that occurs as a result of long-term stress in work and family life, is also linked to several negative outcomes, just like ostracism [

10].

4. Results

The correlation values with regard to the scales used to collect data are presented in

Table 3.

As shown in

Table 3, there was a negative correlation between PRS-SF and OOS (r = −0.68,

p < 0.01) and BSI-SF (r = −0.378,

p < 0.01) direction. On the other hand, there was a positive correlation (r = 0.348,

p < 0.1) between ostracism and teacher burnout levels. These results indicate that the increase in the level of psychological resilience of teachers causes a decrease in their organizational ostracism and burnout. Similarly, the increase in teachers’ organizational ostracism causes an increase in their burnout.

The VIF and tolerance values for the two variables in the measurement model are presented in

Table 4.

VIF values should be less than 10, and tolerance values should be greater than 0.10 [

117]. The results in

Table 3 show that there is no multicollinearity problem among the variables investigated in the study. The mean, standard deviation, skewness, and kurtosis values for the variables in the measurement model are presented in

Table 5.

One of the prerequisites for path analysis is that the data set exhibits a normal distribution. The analysis for the current study showed that the skewness and kurtosis values for each variable were within acceptable limits, and the data showed a normal distribution (see

Table 5). The results in

Table 5 show that PRS-SF values range from 1.00 to 5.00, and values have an arithmetic mean score of 1.27 (SD = 0.589). Values for the OOS range from 1.00 to 5.00, with an arithmetic mean score of 3.52 (SD = 0.699). Values on the BSI-SF scale ranged between 1.00 and 7.00, with an arithmetic mean value of 2.78 (SD = 1.289). These results indicate that teachers’ arithmetic mean scores for psychological resilience were quite low (

= 1.27). On the other hand, teachers’ arithmetic mean scores for organizational ostracism and burnout are higher than their psychological resilience scores. It is extremely important that organizational ostracism and burnout scores should decrease to ensure the effectiveness of the education system. Likewise, a high level of psychological resilience is significant in enhancing teachers’ ability to cope with organizational ostracism and burnout.

4.1. Assessment of Measurement Model

The CFA results for the measurement tools used in SEM should be repeated with the existing data set. For this purpose, the relevant analyses of the scales used in the study were made, and the AVE (average variance extracted) and CR (composite reliability) values were presented in

Table 6, whilst the fit indices were presented in

Table 7.

As shown in

Table 6, the Cronbach Alpha scores vary between 0.86 and 0.97. AVE values greater than 0.50 and a CR coefficient greater than 0.70 are accepted as an indication of the convergent validity and reliability of the structure [

121]. Accordingly, the convergent validity and reliability of the constructs can be considered to be sufficient according to the AVE and CR values in

Table 6.

PRS-SF consists of six items, and the items were accumulated in a single factor. Since the three items in the scale were reverse-coded, analysis was made by re-coding them. The measurement model of the PRS-SF was tested using first-level CFA. All of the paths related to the items in the scale were determined to be statistically significant at the 0.01 level. The fit index values were calculated as χ

2/df = 3.4262, GFI = 0.938 AGFI = 0.914, IFI = 0.908, TLI = 0.907, CFI = 0.917, and RMSEA = 0.078. CFA results showed that the χ

2/df, GFI, IFI, TLI, CFI, and RMSEA values were within the acceptable range of fit indices (see

Table 7).

The OOS consists of 14 items and two dimensions. The first five items in the scale belonged to the dimension of “Isolation”, and the remaining nine items to the dimension of “Nihilation”. The first level CFA results showed that the paths of all 14 items in the scale were statistically significant at the 0.01 level. The fit index values of the scale were χ

2/df = 3.694, GFI = 0.899, IFI = 0.933, CFI = 0.933, AGFI = 0.897, TLI = 0.916, and RMSEA = 0.079, which are within the acceptable range of fit indices (see

Table 7).

The BSI-SF consists of one dimension with 10 items. The first level CFA results showed that all of the paths related to the 10 items in the scale were statistically significant at the 0.01 level. The fit index values for the BSI-SF were found to be χ2/df = 3.462, GFI = 0.899, AGFI = 0.914, IFI = 0.908, TLI = 0.907, CFI = 0.917, and RMSEA = 0.078. These results indicate that the fit index values are in the acceptable range.

4.2. Assessment of the Structural Model

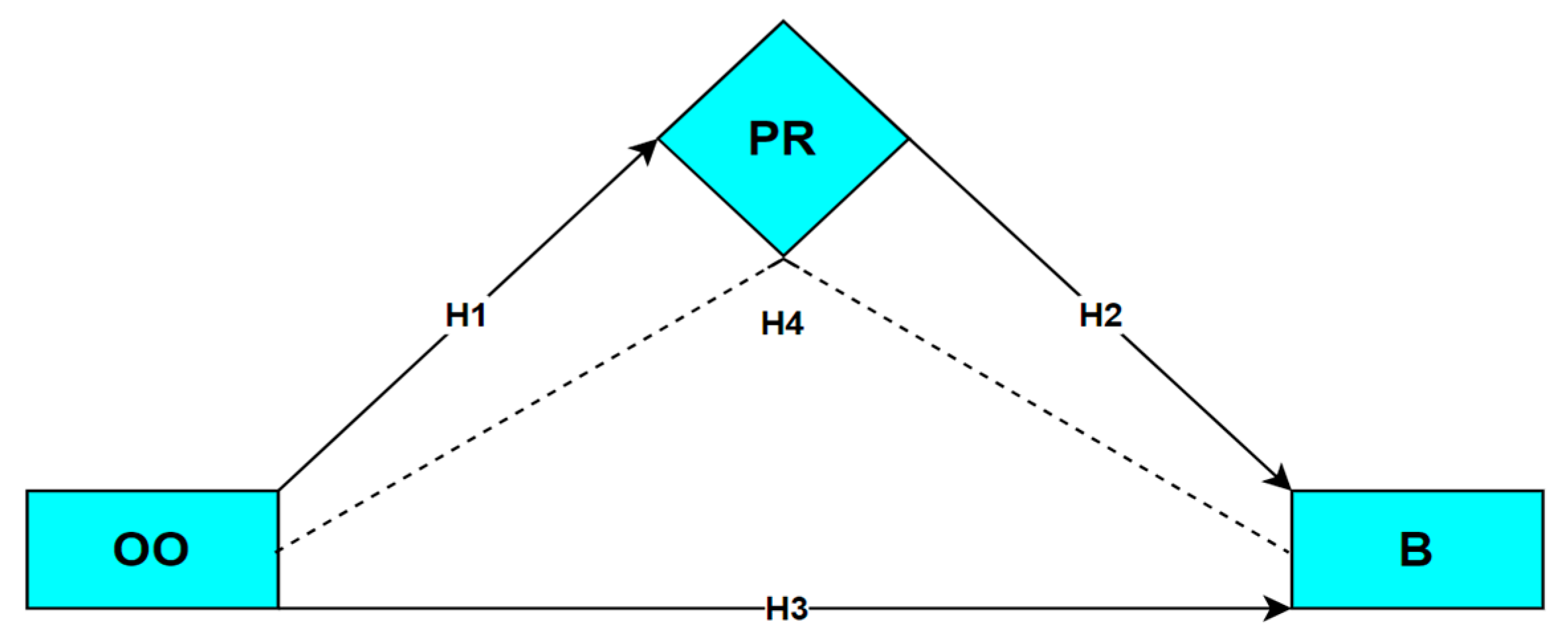

The hypothetical model presented in

Figure 2 was tested with structural equation modeling (SEM). Hypothetical relationships between teachers’ psychological resilience, organizational ostracism, and burnout levels were analyzed. In addition, the mediating effect of psychological resilience on the relationship between organizational ostracism and burnout was tested. The results regarding the direct and indirect relationships between the study variables were as follows: organizational ostracism had a statistically significant positive effect on burnout (t = 6.267,

p < 0.01, β = 0.361), but a statistically significant negative effect on psychological resilience (t = −2.995,

p < 0.01, β = −0.188). Likewise, psychological resilience had a statistically significant negative effect on burnout (t = 3.46,

p < 0.01, β = −0.284). These results show that the hypothetical model is suitable for the mediation test. Based on these findings, the mediating role of psychological resilience in the relationship between organizational ostracism and burnout was evaluated, and the results were presented in

Figure 3.

Before testing the model, some slight modifications were made in the measurement models in order to increase the fit index values of the scales. The final analysis showed that the standardized path coefficient between the BSI-SF and OOS was 0.31, between BSI-SF and PRS-SF was −0.28, and the path coefficient was −0.28. All of the paths were found to be statistically significant at the 0.01 level.

In addition, a statistically significant positive correlation was found between organizational ostracism and burnout (see

Figure 3). The fit indices of the hypothetical model were calculated as χ

2/df = 2.901, which is in the perfect-fit range. The GFI = 0.901, AGFI = 0.899, IFI = 0.951, TLI (NNFI) = 0.941, CFI = 0.950, and RMSEA = 0.079 values were also found to be in the acceptable-fit range. These results indicated that the hypothetical model was confirmed.

Table 8 shows that the standardized regression coefficient between organizational ostracism and burnout is 0.306, which indicates a positive relationship between both variables. Organizational ostracism explains 73.2% of the total variance in burnout. According to Gignac and Szodorai [

122] and Kline [

111], an effect size of around 0.10 is weak, an effect size of about 0.20 is moderate, and an effect size of around 0.30 is large. In light of these specifications, findings from this study showed that organizational ostracism was a strong predictor of burnout.

The standardized regression coefficient between teachers’ organizational ostracism and psychological resilience levels was determined as −0.193 (see

Table 7), which indicates that there is a negative relationship between psychological resilience and organizational ostracism. According to this finding, the increase in teachers’ psychological resilience will cause a decrease in their organizational ostracism. The psychological resilience of teachers explains the 33.8% of the variance in organizational ostracism. The standardized regression coefficient between psychological resilience and organizational ostracism shows the existence of a large effect size, which indicates that teachers’ psychological resilience significantly predicts their likelihood of experiencing organizational ostracism negatively.

In addition, while analyzing the mediating effect of resilience in the relationship between organizational ostracism and burnout, it was a prerequisite to investigate the mediating role of another variable in the relationship between the variables. As a result of the analysis, organizational ostracism was found to have a statistically significant positive effect on burnout (t = 6.267, p < 0.01, β = 0.361). However, organizational ostracism was found to have a statistically significant negative effect on psychological resilience (t = −2.995, p < 0.01; β = −0.188). Likewise, psychological resilience was found to have a statistically significant negative effect on burnout (t = 3.46, p < 0.01, β= −0.284). However, the results showed that the relationship between organizational ostracism and burnout decreased (β = 0.31, p < 0.01) with the mediating effect of psychological resilience, but this and other predictive relationships did not lose their statistical significance. This finding reveals that psychological resilience had a mediating role in the relationship between organizational ostracism and burnout.

5. Discussion

This study investigated the relationship between teachers’ psychological resilience, burnout, and organizational ostracism. In order to test the hypothetical relationships between these variables, structural equation modeling (SEM) was used, and the conceptual model was tested with path analysis.

The findings of the study showed that teachers’ psychological resilience was generally low. While psychological resilience reduces the effect of negative moods on psychological health, it increases the effect of positive moods [

123]. Ulukan [

124], in his study with a cohort of 336 teachers, examined the relationship between happiness and resilience and found a moderately positive relationship between these variables. In the same study, it was stated that stressed and aggressive teachers exhibited lower levels of psychological resilience compared to calm and peaceful teachers. Gu and Day [

31] stated that a person might show resilience in certain situations, occupations, or life stages, but the level of resilience may change in time and place. Zadok-Gurman et al. [

110] investigated the effect of inquiry-based stress reduction (IBSR) intervention on teachers’ well-being, resilience, and burnout during the COVID-19 pandemic. While psychological resilience was high in the experimental group to which IBSR was applied, it was observed to be low in the control group. In a study conducted by Dereceli [

125], it was concluded that stress during the COVID-19 period negatively affected psychological resilience. These results show that the psychological resilience of people was negatively affected during the COVID-19 period, most probably due to high levels of stress, fear, and boredom. COVID-19 presented a unique set of stressors and psychological trauma-related challenges for the employees. Studies investigating the effect of social support programs that would increase the psychological resilience of employees [

126,

127] showed that the stress experienced during the COVID-19 period negatively affected psychological resilience, so social support for the employees was crucial. Liu et al. [

128] determined a high level of psychological resilience in teachers. Similarly, Gönen and Koca Ballı [

129] determined a moderate level of psychological resilience in teachers. These inconsistent findings could be explained by several factors, such as the availability of social support, the nature and quality of initial teacher education, and the characteristics of school structure and climate. Moreover, as teachers in the current study exhibited a low level of psychological resilience, redesigning school structure and climate in a way to provide support and increase teachers’ resilience should be seriously regarded since resilience is a significant protective factor in the face of inevitable challenges of work life [

130].

Another finding of the current study showed that teachers experienced a high level of organizational ostracism. There are studies showing that teachers are sometimes exposed to ostracism in their work context [

51]. For instance, in a study on K–12 teachers by Eickholt and Goodboy [

6], the effect of organizational ostracism on the commitment to school and attitudes towards the teaching profession was observed. The results of the study showed that teachers were rarely exposed to organizational ostracism, yet, when experienced, it affected teachers’ commitment to school and profession negatively. Similarly, in a study conducted by Naz et al. [

64], it was determined that teachers moderately experienced organizational ostracism. When these results are considered cumulatively, it can be said that ostracism could be one of the serious problems awaiting teachers in their work environments and could result in outcomes detrimental to their well-being and performance [

52,

76].

The results of the current study also revealed that the levels of teachers’ burnout are high, which might not be a surprising result as they were found to have lower levels of psychological resilience and higher levels of perceived ostracism. However, these teachers could also have experienced higher levels of burnout due to some other reasons. Some studies in the literature also revealed that teachers experience high levels of burnout [

94]. Burnout, defined as a response to long-term exposure to chronic emotional and interpersonal stressors at work [

81], could result from their constant efforts to maintain high performance as expected from them [

93]. Teachers who experience burnout are more likely to experience negative emotions in the classroom, have negative attitudes toward their students, and may feel inadequate and ineffective in coping with the problems they experience in the profession [

131]. In addition, during the COVID-19 process, stress and burnout increased significantly among teachers who had to continue emergency distance education instead of face-to-face education. Vargas Rubilar and Oros [

101], who examined stress and burnout with 9058 teachers during the COVID-19 pandemic period, emphasized that teachers with higher levels of stress had also experienced higher professional burnout. Moreover, they stated that factors such as lack of face-to-face contact with people, pandemic-related concerns, and excessive workload significantly increased their levels of stress, which might have caused burnout. Yu et al. [

102] also found that teachers’ perceived stress was positively related to job burnout and revealed that there was a negative relationship between self-efficacy and job burnout. Their findings might indicate that teachers’ burnout could result from their lower levels of self-efficacy, and thus supporting their self-efficacy could help decrease or overcome burnout. These results support the findings of the current study and highlight the significance of devising interventions to help teachers overcome burnout to enable the sustainability of their well-being and teaching performance. Establishing a more supportive and positive school climate, building teachers’ self-efficacy and resilience through professional development incentives, eliminating stressors as much as possible, and developing teachers’ stress management capacities could help diminish their likelihood of experiencing burnout.

The current study also determined a negative relationship between organizational ostracism and psychological resilience. Yang Woon [

74] stated that organizational ostracism had negative psychological, behavioral, and organizational consequences for both employees and employers. Psychological resilience, on the other hand, is defined as the individual’s positive adaptation to difficulties that arise in different aspects and phases of work [

18]. While organizational ostracism is related to negative behaviors, resilience expresses a positive adjustment. Therefore, a negative relationship between these two variables could be expected. Waldeck et al. [

132], in their study on resilience to ostracism, emphasized that some people may be partially supported by external factors and develop resilience to ostracism. They also identified resilience as a potential moderator in determining how people cope with ostracism. In a study conducted by Haq [

133], the relationship between ostracism in the workplace, psychological capital, job performance, job stress, and intention to leave was investigated, and the results showed that there was a negative relationship between psychological capital and ostracism. Similarly, in a study by Jiang et al. [

134], a negative relationship was observed between ostracism and resilience. Based on these results, it can be interpreted that teachers with lower levels of psychological resilience tend to have higher levels of perceived ostracism. Accordingly, it can be stated that helping teachers build stronger psychological resilience could also help them face the challenges in the workplace better. In fact, as the results of the current study showed, the same could hold true for burnout. The analysis yielded a significant positive relationship between organizational ostracism and burnout. When teachers are exposed to organizational ostracism, they may experience negative feelings about their work environment and the profession [

6]. In their study examining interpersonal maltreatment in the workplace and burnout among teachers, Suela et al. [

9] found that workplace maltreatment (ostracism, rudeness, unwanted sexual attention, abusive supervision, and undermining) was positively associated with burnout. In another study, Naz et al. [

64] found a significant positive relationship between ostracism and teacher burnout.

The findings of this study exhibited that psychological resilience negatively predicts burnout, indicating that increasing the psychological resilience of teachers will decrease their burnout levels. Similar results were obtained in previous studies. For instance, in a study conducted by Fathi and Saedian [

43], the relationship between teachers’ self-efficacy, resilience, and burnout was investigated, which showed that resilience negatively predicted teachers’ burnout. Likewise, Ismail et al. [

32] explored the relationship between emotional, spiritual, physical, and social intelligence, resilience, and burnout. They found a negative relationship between teachers’ psychological resilience and burnout. Liu et al. [

36] concluded that teachers’ resilience predicted job burnout negatively. In different studies in the literature [

33,

35,

44,

45,

109,

110,

134], a negative relationship between teachers’ psychological resilience and their burnout was observed.

The current study also showed that psychological resilience had a mediating role in the relationship between organizational ostracism and burnout. This finding indicates that while teachers’ exposure to organizational ostracism affects their burnout positively, psychological resilience will reduce this effect and lower their burnout levels. According to the results of Jiang et al.’s [

134] study explaining the relationship between ostracism and deviant behavior, as well as the mediating role of emotional exhaustion and the moderator role of resilience, resilience had a mediating effect on the relationship between ostracism and emotional burnout in the workplace. Existing studies in the literature showed that psychological resilience could be a significant moderating variable in the relationship between several other variables. For example, Uzun and Tortumlu [

135] examined the mediating effect of resilience and hope in the effect of occupational burnout on life satisfaction. They determined that psychological resilience had a partial mediating effect on the relationship between burnout and life satisfaction. In the study conducted by Arpacı and Gündoğan [

136], psychological resilience was found to significantly mediate the relationship between mindfulness and nomophobia. Similarly, the results of the research conducted by Liu et al. [

128] revealed that psychological resilience had a mediating effect on the relationship between test anxiety and emotion regulation. These results indicate that developing teachers’ psychological resilience not only results in positive outcomes for the teachers, students, and schools but also helps eliminate the negative factors that could inhibit their success and well-being.

Limitations and Implications

The results of the current study suggest significant implications for both teacher education and educational management professionals. As stated earlier, scholars contend that teachers’ psychological resilience could be developed during the initial teacher education and should be supported intermittently throughout their professional lives with in-service training programs. Developing teachers’ capabilities to access support, increasing their self-awareness, supporting their self-efficacy beliefs, and equipping them with resources to enable self-protection in the face of challenging events could support their well-being and performance at school [

20,

137]. In addition, teachers’ psychological resilience is closely associated with their social and organizational environment, and social support could leverage their resilience to a greater extent. By taking this into consideration, school administrators should strive to facilitate teachers’ resilience by constructing a more positive and supportive work environment in schools, which could also reduce the risk of exposure to negative outcomes such as burnout or ostracism.

Although the current study contributed to the literature significantly, it also bears some limitations. First, the current study was conducted in an Eastern context and in a rather centralized educational system; hence, the results could be influenced by the cultural and structural aspects of this context. However, similar studies conducted in a Western context, or comparative studies in this regard, could yield different results and enhance our understanding of their relationships and outcomes. In addition, the current study was conducted right after the COVID-19 pandemic, between the years 2021 and 2022, and the unique characteristics of the pandemic period, such as high levels of stress and low levels of social support, could have influenced participants’ behavioral and affective states. Therefore, the results of the current study could be interpreted under these circumstances, and future studies could shed light on this argument. Another limitation could have resulted from data collection via sell-assessment scales. Although participants were informed about the research purpose and about the variables tested in the study, they might have given biased answers. This, in fact, holds true for many quantitative research methods using scales to collect data but still warrants notification so that the results are interpreted accordingly.