Musical Enjoyment and Reward: From Hedonic Pleasure to Eudaimonic Listening

Abstract

1. Introduction

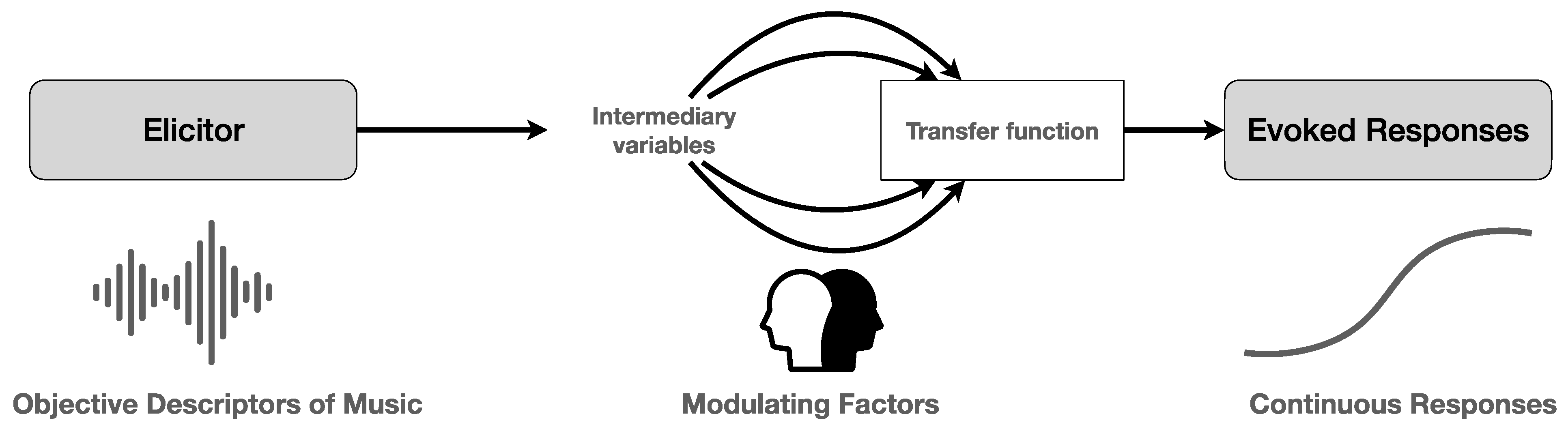

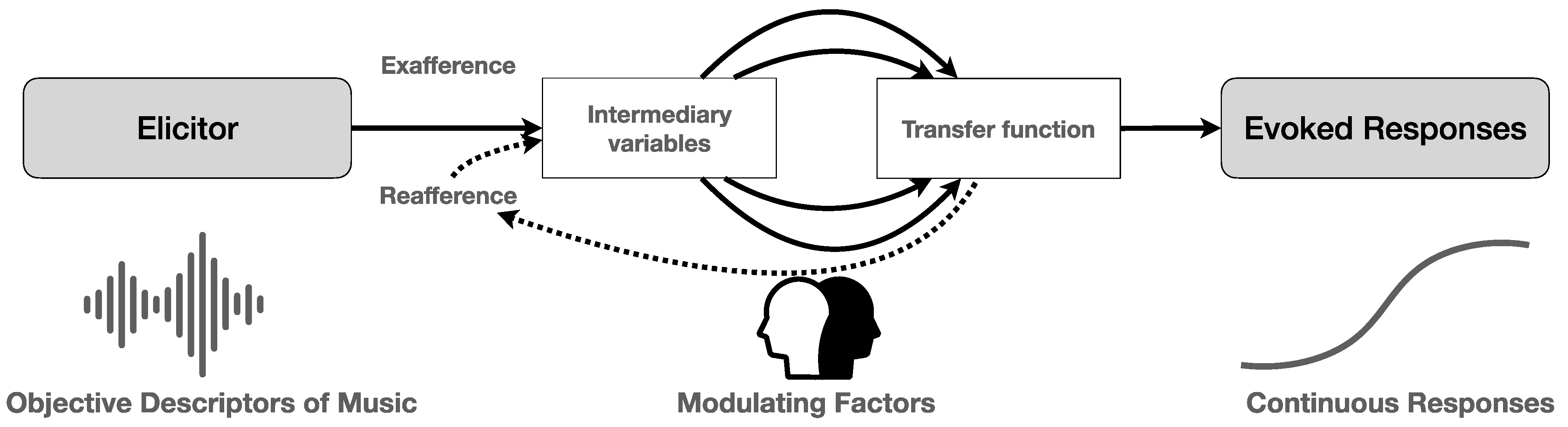

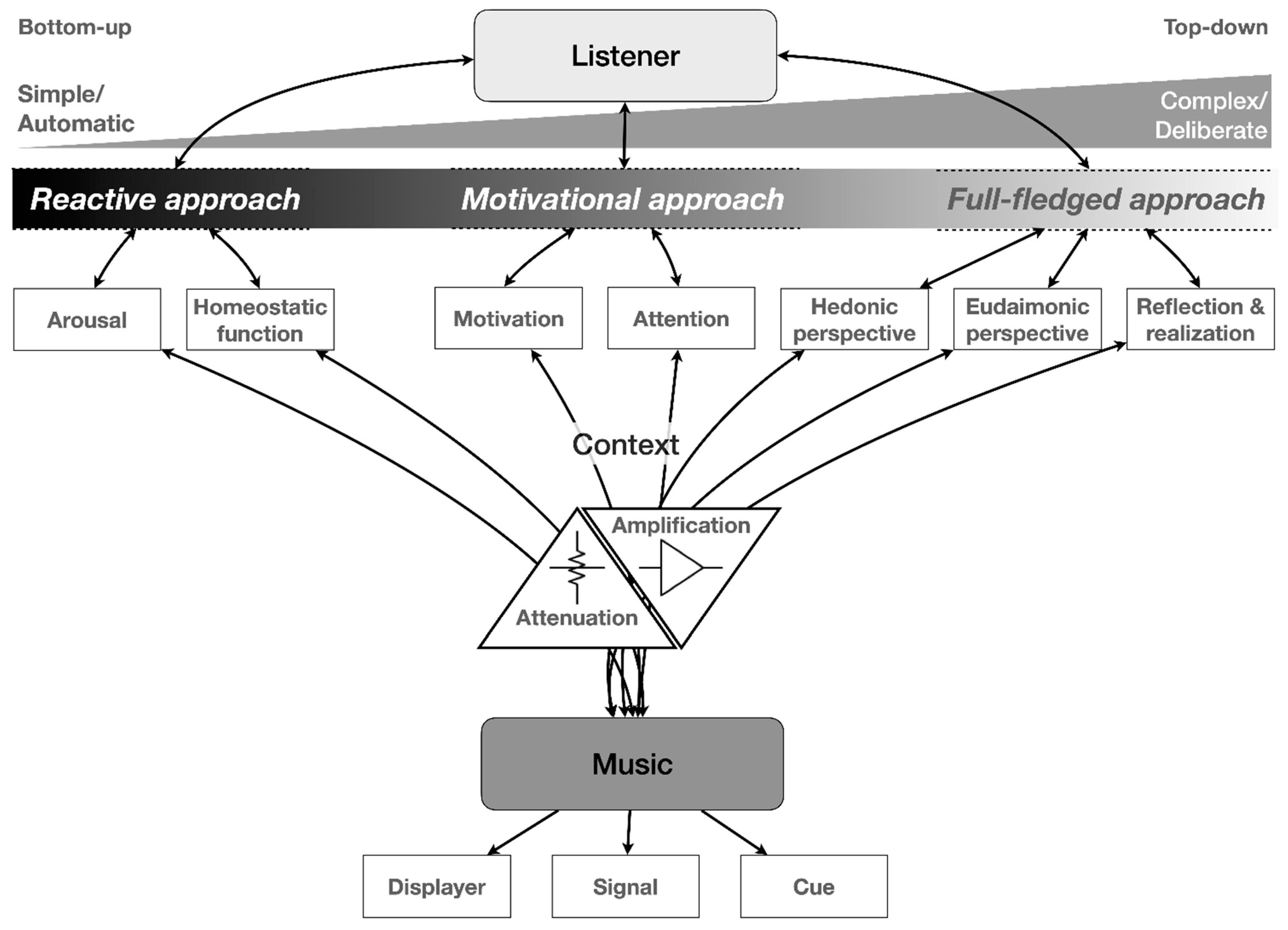

2. Music Listening: From Acoustic Processing to Full-Fledged Experience

2.1. Coping with the Sounds

2.2. Music Affects Our Biological Systems: Affective-Emotional Impact

2.3. The Role of Disposition and Active Engagement

3. Rewards of Music Listening

3.1. Music and Pleasure: The Role of Endogenous Opiates

3.2. Aesthetic Experience and Reward: Peak Experiences, Chills and Thrills

4. Listening beyond the Sounds: Eudaimonic Pleasure

4.1. From Sensory Pleasure to Eudaimonic Enjoyment

4.2. Listening to Music for Self-Reflection and Self-Realization

5. Adaptive and Maladaptive Listening

6. Conclusions and Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Seligman, M.; Csikszentmihalyi, M. Positive psychology: An introduction. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jayawickreme, E.; Forgeard, M.; Seligman, M. The Engine of Well-Being. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2012, 16, 327–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.; Deci, E. On Happiness and Human Potentials: A Review of Research on Hedonic and Eudaimonic Well-Being. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 141–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heintzelman, S. Eudaimonia in the contemporary science of subjective well-being: Psychological well-being, self-determination, and meaning in life. In Handbook of Well-Being; Diener, E., Oishi, S., Tay, L., Eds.; DEF Publishers: Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 2018; Available online: https://www.nobascholar.com/chapters/18/download.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2022).

- Huta, V. Eudaimonic and hedonic orientations: Theoretical considerations and research findings. In Handbook of Eudaimonic Wellbeing; Vittersø, J., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 215–230. [Google Scholar]

- Huta, V.; Waterman, A.S. Eudaimonia and its distinction from hedonia: Developing a classification and terminology for understanding conceptual and operational definitions. J. Happiness Stud. 2016, 15, 1425–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huta, V.; Ryan, R. Pursuing pleasure or virtue: The differential and overlapping well-being benefits of hedonic and eudaimonic motives. J. Happiness Stud. 2010, 11, 735–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martela, F.; Sheldon, K. Clarifying the Concept of Well-Being: Psychological Need Satisfaction as the Common Core Connecting Eudaimonic and Subjective Well-Being. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2019, 23, 458–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eerola, T.; Vuoskoski, J.; Kautiainen, H.; Peltola, H.; Putkinen, V.; Schäfer, K. Being moved by listening to unfamiliar sad music induces reward-related hormonal changes in empathic listeners. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2021, 1502, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huron, D. Why is sad music pleasurable? A possible role for prolactin. Music. Sci. 2011, 5, 146–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.; Gonzaga, G.; Klein, L.; Hu, P.; Greendale, G.; Seeman, T. Relation of oxytocin to psychological stress responses and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical axis activity in older women. Psychosom. Med. 2006, 68, 238–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Burg, E.; Neumann, I. Bridging the gap between GPCR activation and behaviour: Oxytocin and prolactin signalling in the hypothalamus. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2011, 43, 200–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreri, L.; Mas-Herrero, E.; Zatorre, R.; Ripollés, P.; Gomez-Andres, A.; Alicart, H.; Olivé, G.; Marco-Pallarés, J.; Antonijoan, R.; Valle, M.; et al. Dopamine modulates the reward experiences elicited by music. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 3793–3798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schultz, W. Updating dopamine reward signals. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2013, 23, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schultz, W. Neuronal reward and decision signals: From theories to data. Physiol. Rev. 2015, 95, 853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maruskin, L.; Thrash, T.; Elliot, A. The Chills as a Psychological Construct: Content Universe, Factor Structure, Affective Composition, Elicitors, Trait Antecedents, and Consequences. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 103, 135–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reybrouck, M. The Musical Code between Nature and Nurture. In The Codes of Life: The Rules of Macroevolution; Barbieri, M., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2008; pp. 395–434. [Google Scholar]

- Reybrouck, M.; Eerola, T. Music and its inductive power: A psychobiological and evolutionary approach to musical emotions. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lartillot, O.; Toiviainen, P. MIR in Matlab (II): A toolbox for musical feature extraction from audio. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Music Information Retrieval, Vienna, Austria, 23–27 September 2007; Available online: http://ismir2007.ismir.net/proceedings/ISMIR2007_p127_lartillot.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2022).

- Alluri, V.; Toiviainen, P.; Jääskeläinen, I.; Glerean, E.; Sams, M.; Brattico, E. Large-scale brain networks emerge from dynamic processing of musical timbre, key and rhythm. NeuroImage 2012, 59, 3677–3689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toiviainen, P.; Alluri, V.; Brattico, E.; Wallentin, M.; Vuust, P. Capturing the musical brain with Lasso: Dynamic decoding of musical features from fMRI data. Neuroimage 2014, 88, 170–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFee, B.; Raffel, C.; Liang, D.; Ellis, D.; McVicar, M.; Battenberg, E.; Nieto, O. librosa: Audio and music signal analysis in Python. In Proceedings of the 14th Python in Science Conference, Austin, TX, USA, 6–12 July 2015; pp. 18–25. [Google Scholar]

- Bays, P.; Flanagan, J.; Wolpert, D. Attenuation of self-generated tactile sensations is predictive, not postdictive. PLoS Biol. 2006, 4, e28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voss, M.; Ingram, J.; Haggard, P.; Wolpert, D. Sensorimotor attenuation by central motor command signals in the absence of movement. Nat. Neurosci. 2006, 9, 26–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullen, K. The vestibular system: Multi-modal integration and encoding of self-motion for motor control. Trends Neurosci. 2012, 35, 185–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jékely, G.; Godfrey-Smith, P.; Keijzer, F. Reafference and the origin of the self in early nervous system evolution. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. 2021, 376, 20190764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reichenbach, A.; Diedrichsen, J. Processing reafferent and exafferent visual information for action and perception. J. Vis. 2015, 15, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Wager, T.; Barrett, L.; Bliss-Moreau, E.; Lindquist, K.; Duncan, S.; Kober, H.; Joseph, J.; Davidson, M.; Mize, J. The neuroimaging of emotion. In Handbook of Emotions; Lewis, M., Haviland-Jones, J., Barrett, L., Eds.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 249–271. [Google Scholar]

- Morawetz, C.; Bode, S.; Derntl, B.; Heekeren, H. The effect of strategies, goals and stimulus material on the neural mechanisms of emotion regulation: A meta-analysis of fMRI studies. Neurosci. Biobehav. R 2017, 72, 111–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kober, H.; Barrett, L.; Joseph, J.; Bliss-Moreau, E.; Lindquist, K.; Wager, T. Functional grouping and cortical-subcortical interactions in emotion: A meta-analysis of neuroimaging studies. NeuroImage 2008, 42, 998–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandl, F.; Corbi, Z.; Bratec, S.; Sorg, C. Cognitive reward control recruits medial and lateral frontal cortices, which are also involved in cognitive emotion regulation: A coordinate-based meta-analysis of fMRI studies. Neuroimage 2019, 200, 659–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panksepp, J.; Trevarthen, C. The neuroscience of emotion in music. In Communicative Musicality: Exploring the Basis of Human Companionship; Malloch, S., Trevarthen, C., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2009; pp. 105–146. [Google Scholar]

- Reybrouck, M. Musical Sense-Making. Enaction, Experience, and Computation; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Schaeffer, P. Traité des Objets Musicaux; Editions du Seuil: Paris, France, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Chion, M. L’Audio-Vision; Nathan: Paris, France, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Kraus, N.; Chandrasekaran, B. Music training for the development of auditory skills. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2010, 11, 599–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuuri, K.; Eerola, T. Formulating a Revised Taxonomy for Modes of Listening. J. New Music Res. 2012, 41, 137–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinbergen, N. On aims and methods of ethology. Z. Tierpsychol. 1963, 20, 410–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott-Phillips, T.; Dickins, T.; West, S. Evolutionary theory and the ultimate- proximate distinction in the human behavioral sciences. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2011, 6, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitch, W. Four principles of bio-musicology. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. 2015, 370, 20140091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maschke, C.; Rupp, T.; Hecht, T. The influence of stressors on biochemical reactions—A review of present scientific findings with noise. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2000, 203, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orians, G.; Heerwagen, J. Evolved responses to landscape. In The Adapted Mind; Barkow, J., Cosmides, L., Tooby, J., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1992; pp. 555–579. [Google Scholar]

- Reybrouck, M.; Podlipniak, P.; Welch, D. Music Listening as Coping Behavior: From Reactive Response to Sense-Making. Behav. Sci. 2020, 10, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazarus, R.; Folkman, S. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Lorenz, K. Vergleichende Verhaltensforschung. Zool. Anz. Suppl. 1939, 12, 69–102. [Google Scholar]

- Lorenz, K. Studies in Animal and Human Behaviour, Vol. 1.; Methuen: London, UK, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, J.; Harper, D. Animal Signals; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Huron, D. The Other Semiotic Legacy of Charles Sanders Peirce: Ethology And Music-Related Emotion. In Music, Analysis, Experience. New Perspectives in Musical Semiotics; Maeder, C., Reybrouck, M., Eds.; Leuven University Press: Leuven, Belgium, 2015; pp. 185–208. [Google Scholar]

- Bradbury, J.; Vehrenkamp, S. Principles of Animal Communication; Sinauer: Sunderland, MA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Krebs, J.; Dawkins, R. Animal Signals: Mind-Reading and Manipulation. In Behavioural Ecology; Krebs, J., Davies, N., Eds.; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1984; pp. 381–402. [Google Scholar]

- Huron, D.; Vuoskoski, J. On the Enjoyment of Sad Music: Pleasurable Compassion Theory and the Role of Trait Empathy. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kottler, J.; Montgomery, M. Theories of crying. In Adult Crying: A Biopsychosocial Approach; Vingerhoets, A., Cornelius, R., Eds.; Brunner-Routledge: Hove, UK, 2001; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Hatten, R. A Theory of Virtual Agency for Western Art Music; Indiana University Press: Bloomington, Indiana, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Parncutt, R.; Kessler, A. Musik als virtuelle Person. In Musikals Ausgewählte Betrachtungsweisen; Flotzinger, R., Ed.; Österreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften: Wien, Austria, 2006; pp. 9–52. [Google Scholar]

- Juslin, P.; Laukka, P. Communication of emotions in vocal expression and music performance: Different channels, same code? Psychol. Bull. 2003, 129, 770–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schutz, M.; Huron, D.; Keeton, K.; Loewer, G. The happy xylophone: Acoustic affordances restrict an emotional palate. Empir. Musicol. Rev. 2008, 3, 126–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisanski, K.; Raine, J.; Reby, D. Individual differences in human voice pitch are preserved from speech to screams, roars and pain cries. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2020, 7, 191642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnal, L.; Flinker, A.; Kleinschmidt, A.; Giraud, A.-L.; Poeppel, D. Human Screams Occupy a Privileged Niche in the Communication Soundscape. Curr. Biol. 2015, 25, 2051–2056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damasio, A. The Feeling of What Happens. Body and Emotion in the Making of Consciousness; Vintage: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Damasio, A. Looking for Spinoza. Joy, Sorrow and the Feeling Brain; Vintage: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Dewey, J. Art as Experience, 2nd ed.; Capricorn Books: New York, NY, USA, 1958. [Google Scholar]

- James, W. Essays in Radical Empiricism; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Reybrouck, M. Musical sense-making between experience and conceptualisation: The legacy of Peirce, Dewey and James. Interdisc. Stud. Musicol. 2014, 14, 176–205. [Google Scholar]

- Reybrouck, M. Music as Environment: An Ecological and Biosemiotic Approach. Beh. Sci. 2015, 5, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippi, P.; Congdon, J.; Hoang, J.; Bowling, D.; Reber, S.; Pašukonis, A.; Hoeschele, M.; Ocklenburg, S.; de Boer, B.; Sturdy, C.; et al. Humans recognize emotional arousal in vocalizations across all classes of terrestrial vertebrates: Evidence for acoustic universals. Proc. R. Soc. B 2017, 284, 20170990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reybrouck, M.; Podlipniak, P.; Welch, D. Music and Noise: Same or Different? What Our Body Tells Us. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Craig, A. How do you feel—Now? The anterior insula and human awareness. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2009, 10, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reybrouck, M.; Podlipniak, P.; Welch, D. Music listening and homeostatic regulation: Surviving and flourishing in a sonic world. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 19, 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochrane, T. Expression and extended cognition. Aesthet. Art Crit. 2008, 66, 329–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brattico, E.; Pearce, M. The Neuroaesthetics of Music. Psychol. Aesthet. Creat. Arts 2013, 7, 48–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zentner, M.; Grandjean, D.; Scherer, K. Emotions Evoked by the Sound of Music: Characterization, Classification, and Measurement. Emotion 2008, 8, 494–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cova, F.; Deonna, J. Being moved. Philos. Stud. 2014, 169, 447–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanich, J.; Wagner, V.; Shah, M.; Jacobsen, T.; Menninghaus, W. Why we like to watch sad films. The pleasure of being moved in aesthetic experiences. Psychol. Aesthet. Creat. Arts 2014, 8, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konečni, V. The aesthetic trinity: Awe, being moved, thrills. Bull. Psychol. Arts 2005, 5, 27–44. [Google Scholar]

- Konečni, V.J. Being moved as one of the major aesthetic emotional states: A commentary on “Being moved: Linguistic representation and conceptual structure. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 343. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kuehnast, M.; Wagner, V.; Wassiliwizky, E.; Jacobsen, T.; Menninghaus, W. Being moved: Linguistic representation and conceptual structure. Front. Psychol. 2014, 5, 1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menninghaus, W.; Wagner, V.; Hanich, J.; Wassiliwizky, E.; Kuehnast, M.; Jacobsen, T. Towards a psychological construct of being moved. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0128451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Immordino-Yang, M.; Damasio, A. We Feel, Therefore We Learn: The Relevance of Affective and Social Neuroscience to Education. Mind Brain Educ. 2007, 1, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Jonathan, N.; Hnasko, R. Dopamine as a Prolactin (PRL) Inhibitor. Endocr. Rev. 2001, 22, 724–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huron, D. Sweet Anticipation: Music and the Psychology of Expectation; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- LeDoux, J. The Emotional Brain: The Mysterious Underpinnings of Emotional Life; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Schubert, E. Enjoyment of Negative Emotions in Music: An Associative Network Explanation. Psychol. Music. 1996, 24, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadal, M.; Skov, M. Introduction to the Special Issue: Toward an Interdisciplinary Neuroaesthetics. Psychol. Aesthet. Creat. Arts 2013, 7, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salimpoor, V.; Zatorre, R.J. Neural interactions that give rise to musical pleasure. Psychol. Aesthet. Creat. Arts 2013, 7, 62–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Digman, J. Personality structure: Emergence of the five-factor model. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 1990, 41, 417–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamorro-Premuzic, T.; Furnham, A. Personality and music: Can traits explain how people use music in everyday life? Br. J. Psychol. 2007, 98, 175–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panksepp, J. Affective Neuroscience: The Foundations of Human and Animal Emotions; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Rentfrow, P.; Goldberg, L.; Levitin, D. The structure of musical preferences: A five-factor model. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2011, 100, 1139–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chanda, M.; Levitin, D. The neurochemistry of music. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2013, 17, 179–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldstein, A. Thrills in response to music and other stimuli. Physiol. Psychol. 1980, 8, 126–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grewe, O.; Nagel, F.; Kopiez, R.; Altenmüller, E. Listening to Music as a Re-Creative Process: Physiological, Psychological, and Psychoacoustical Correlates of Chills and Strong Emotions. Music Percept. 2007, 24, 297–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCrae, R. Aesthetic chills as a universal marker of openness to experience. Motiv. Emot. 2007, 31, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvia, P.; Nusbaum, E. On Personality and Piloerection: Individual Differences in Aesthetic Chills and Other Unusual Aesthetic Experiences. Psychol. Aesthet. Creat. Arts 2011, 5, 208–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuoskoski, J.; Thompson, W.; McIlwain, D.; Eerola, T. Who enjoys listening to sad music and why? Music Percept. 2012, 29, 311–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCrae, R.; Costa, P. Conceptions and correlates of openness to experience. In Handbook of Personality Psychology; Hogan, R., Johnson, J., Briggs, S., Eds.; Academic Press: Orlando, FL, USA, 1997; pp. 825–847. [Google Scholar]

- DeYoung, C. Openness/Intellect: A dimension of personality reflecting cognitive exploration. In APA Handbook of Personality and Social Psychology, Personality Processes and Individual Differences, Vol. 4; Mikulincer, M., Shaver, R., Cooper, M., Larsen, R., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2014; pp. 369–399. [Google Scholar]

- Ladinig, O.; Schellenberg, E.G. Liking Unfamiliar Music: Effects of Felt Emotion and Individual Differences. Psychol. Aesthet. Creat. Arts 2012, 6, 146–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurlemann, R.; Patin, A.; Onur, O.; Cohen, M.; Baumgartner, T.; Metzler, S.; Dziobek, I.; Gallinat, J.; Wagner, M.; Maier, W.; et al. Oxytocin enhances amygdala-dependent, socially reinforced learning and emotional empathy in humans. J. Neurosci. 2010, 30, 4999–5007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lackner, C.; Bowman, L.; Sabbagh, M.A. Dopaminergic functioning and preschoolers’ theory of mind. Neuropsychologia 2010, 48, 1767–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamay-Tsoory, S.; Aharon-Peretz, J. Dissociable prefrontal networks for cognitive and affective theory of mind: A lesion study. Neuropsychologia 2007, 45, 3054–3067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shamay-Tsoory, S.; Aharon-Peretz, J.; Perry, D. Two systems for empathy: A double dissociation between emotional and cognitive empathy in inferior frontal gyrus versus ventromedial prefrontal lesions. Brain 2009, 132, 617–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shamay-Tsoory, S. The neural bases for empathy. Neuroscientist 2011, 17, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eerola, T.; Vuoskoski, J.; Kautiainen, H. Being moved by unfamiliar sad music is associated with high empathy. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vuoskoski, J.; Eerola, T. The Pleasure Evoked by Sad Music is Mediated by Feelings of Beind Moved. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reybrouck, M.; Brattico, E. Neuroplasticity beyond Sounds: Neural Adaptations Following Long-Term Musical Aesthetic Experiences. Brain Sci. 2015, 5, 69–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reybrouck, M.; Vuust, P.; Brattico, E. Brain Connectivity Networks and the Aesthetic Experience of Music. Brain Sci. 2018, 8, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, K.; Ashley, R.; Strait, D.; Kraus, N. Art and science: How musical training shapes the brain. Front. Psychol. 2013, 4, 713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachs, M.; Ellis, R.; Schlaug, G.; Loui, P. Brain connectivity reflects human aesthetic responses. Soc. Cogn. Affect Neurosci. 2016, 11, 884–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansen-Berg, H. Behavioural relevance of variation in white matter microstructure. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 2010, 23, 351–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkinson, C.; Wheatley, T. Relating anatomical and social connectivity: White matter microstructure predicts emotional empathy. Cereb. Cortex 2014, 24, 614–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnea-Goraly, N.; Kwon, H.; Menon, V.; Eliez, S.; Lotspeich, L.; Reiss, A. White matter structure in autism: Preliminary evidence from diffusion tensor imaging. Biol. Psychiatry 2004, 55, 323–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnstone, T.; van Reekum, C. Failure to regulate: Counterproductive recruitment of top-down prefrontal-subcortical circuitry in major depression. J. Neurosci. 2007, 27, 8877–8884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mas-Herrero, E.; Zatorre, R.; Rodriguez-Fornells, A.; Marco-Pallarés, J. Dissociation between musical and monetary reward responses in specific musical anhedonia. Curr. Biol. 2014, 24, 699–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blood, A.J.; Zatorre, R.J. Intensely pleasurable responses to music correlate with activity in brain regions implicated in reward and emotion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 11818–11823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Molina, N.; Mas-Herrero, E.; Rodríguez-Fornells, A.; Zatorre, R.; Marco-Pallarés, J. Neural correlates of specific musical anhedonia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, E7337–E7345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mas-Herrero, E.; Karhulahti, M.; Marco-Pallares, J.; Zatorre, R.; Rodriguez-Fornells, A. The impact of visual art and emotional sounds in specific musical anhedonia. Prog. Brain Res. 2018, 237, 399–413. [Google Scholar]

- Mas-Herrero, E.; Dagher, A.; Zatorre, R. Modulating musical reward sensitivity up and down with transcranial magnetic stimulation. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2018, 2, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salimpoor, V.; Zald, D.; Zatorre, R.; Dagher, A.; McIntosh, A. Interactions between the nucleus accumbens and auditory cortices predicts music reward value. Science 2013, 340, 216–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindquist, K.; Wager, T.; Kober, H.; Bliss-Moreau, E.; Feldman Barrett, L. The brain basis of emotion: A meta-analytic review. Behav. Brain Sci. 2012, 35, 121–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brattico, E. From pleasure to liking and back: Bottom-up and top-down neural routes to the aesthetic enjoyment. In Art, Aesthetics, and the Brain; Huston, J., Nadal, M., Mora, F., Agnati, L., Cela Conde, C.J., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2015; pp. 303–318. [Google Scholar]

- Shizgal, P. On the neural computation of utility. In Well-Being: The Foundations of Hedonic Psychology; Kahneman, D., Diener, E., Schwarz, N., Eds.; Russell Sage Found: New York, NY, USA, 1999; pp. 500–524. [Google Scholar]

- Oishi, S.; Diener, E.; Lucas, R.; Suh, E. Cross-cultural variations in predictors of life satisfaction: Perspectives from needs and values. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 1999, 25, 980–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, C. Personal control and wellbeing. In Well-Being: The Foundations of Hedonic Psychology; Kahneman, D., Diener, E., Schwarz, N., Eds.; Russell Sage Found: New York, NY, USA, 1999; pp. 288–301. [Google Scholar]

- Leder, H.; Belke, B.; Oeberst, A.; Augustin, D. A model of aesthetic appreciation and aesthetic judgments. Br. J. Psychol. 2004, 95, 489–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perlovsky, L. Musical emotions: Functions, origins, evolution. Phys. Life Rev. 2010, 7, 2–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perlovsky, L. Neural mechanisms of the mind, Aristotle, Zadeh, ad fMRI. IEEE Trans. Neural. Netw. 2010, 21, 718–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brattico, E.; Bogert, B.; Jacobsen, T. Toward a neural chronometry for the aesthetic experience of music. Front. Psychol. 2013, 4, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kringelbach, M. The human orbitofrontal cortex: Linking reward to hedonic experience. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2005, 6, 691–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kringelbach, M. The hedonic brain: A functional neuroanatomy of human pleasure. In Pleasures of the Brain; Kringelbach, M., Berridge, K., Eds.; University Press: Oxford, UK, 2010; pp. 202–221. [Google Scholar]

- Peciña, S.; Smith, K.; Berridge, K. Hedonic hot spots in the brain. Neuroscientist 2006, 12, 500–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peciña, M.; Berridge, K. Hedonic hotspot in nucleus accumbens shell: Where do mu-opioids cause increased hedonic impact of sweetness? J. Neurosci. 2005, 14, 11777–11786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuust, P.; Kringelbach, M. The Pleasure of Making Sense of Music. Interdiscip. Rev. 2010, 35, 66–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kringelbach, M.; Berridge, K. Towards a functional neuroanatomy of pleasure and happiness. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2009, 13, 479–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peck, K.; Girard, T.; Russo, F.; Fiocco, A. Music and memory in Alzheimer’s disease and the potential underlying mechanisms. JAD 2016, 51, 949–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salimpoor, V.; Benovoy, M.; Larcher, K.; Dagher, A.; Zatorre, R. Anatomically distinct dopamine release during anticipation and experience of peak emotion to music. Nat. Neurosci. 2011, 14, 257–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heinrichs, M.; Baumgartner, T.; Kirschbaum, C.; Ehlert, U. Social support and oxytocin interact to suppress cortisol and subjective responses to psychosocial stress. Biol. Psychiatry 2003, 54, 1389–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirsch, P.; Esslinger, C.; Chen, Q.; Mier, D.; Lis, S.; Siddhanti, S.; Gruppe, H.; Mattay, V.; Gallhofer, B.; Meyer-Lindenberg, A. Oxytocin Modulates Neural Circuitry for Social Cognition and Fear in Humans. J. Neurosci. 2005, 25, 11489–11493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fitzgerald, P.; Dinan, T. Prolactin and dopamine: What is the connection? A Review Article. J. Psychopharmacol. 2008, 22, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eerola, T.; Vuoskoski, J.; Peltola, H.-R.; Putkinen, V.; Schäfer, K. An integrative review of the enjoyment of sadness associated with music. Phys. Life Rev. 2018, 25, 100–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ladinig, O.; Brooks, C.; Hansen, N.; Horn, K.; Huron, D. Enjoying sad music: A test of the prolactin theory. Music. Sci. 2021, 25, 429–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, T. Oxytocin, motivation and the role of dopamine. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2014, 119, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bethlehem, R.; Baron-Cohen, S.; van Honk, J.; Auyeung, B.; Bos, P. The oxytocin paradox. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2014, 8, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemp, A.; Guastella, A. The Role of Oxytocin in Human Affect: A Novel Hypothesis. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2011, 20, 222–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrotta, G. Oxytocin and the role of “regulator of emotions”: Definition, neurobiochemical and clinical contexts, practical applications and contraindications. Arch Depress. Anxiety 2020, 6, 001–005. [Google Scholar]

- Juslin, P.; Laukka, P. Expression, Perception, and Induction of Musical Emotions: A Review and a Questionnaire Study of Everday Listening. J. New Music Res. 2004, 33, 217–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience; Harper and Row: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Krippner, S. The plateau experience: A. H. Maslow and others. J. Transpers. Psychol. 1972, 4, 107–120. [Google Scholar]

- Maslow, A.H. Toward a Psychology of Being; Van Nostrand Reinhold Company: New York, NY, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Rickard, N. Intense emotional responses to music: A test for the physiological arousal hypothesis. Psychol. Music 2004, 32, 371–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salimpoor, V.; Benovoy, M.; Longo, G.; Cooperstock, J.; Zatorre, R. The rewarding aspects of music listening are related to degree of emotional arousal. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e7487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bannister, S. Distinct varieties of aesthetic chills in response to multimedia. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0224974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelowski, M.; Markey, P.; Forster, M.; Gerger, G.; Leder, H. Move me, astonish me... delight my eyes and brain: The Vienna Integrated Model of top-down and bottom-up processes in Art Perception (VIMAP) and corresponding affective, evaluative, and neurophysiological correlates. Phys. Life Rev. 2017, 21, 80–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konečni, V.; Wanic, R.; Brown, A. Emotional and Aesthetic Antecedents and Consequences of Music-Induced Thrills. Am. J. Psychol. 2007, 120, 619–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huron, D.; Margulis, E. Musical expectancy and thrills. In Handbook of Music and Emotion: Theory, Research, Applications; Juslin, P.N., Sloboda, J.A., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 575–604. [Google Scholar]

- Sloboda, J. Music structure and emotional response: Some empirical findings. Psychol. Music 1991, 19, 110–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bannister, S.; Eerola, T. Suppressing the Chills: Effects of Musical Manipulation on the Chills Response. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halpern, D.; Blake, R.; Hillenbrand, J. Psychoacoustics of a chilling sound. Percept. Psychophys 1986, 39, 77–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schoeller, F.; Perlovsky, L. Aesthetic Chills: Knowledge-Acquisition, Meaning-Making, and Aesthetic Emotions. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wassiliwizky, E.; Wagner, V.; Jacobsen, T.; Menninghaus, W. Art-elicited chills indicate states of being moved. Psychol. Aesthet. Creat. Arts 2015, 9, 405–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bannister, S.; Eerola, T. Vigilance and social chills with music: Evidence for two types of musical chills. Psychol. Aesthet. Creat. Arts 2021. advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brattico, E.; Brattico, P.; Jacobsen, T. The origins of the aesthetic enjoyment of music—A review of the literature. Mus. Sci. 2009, 13, 15–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, D.; Diener, E.; Schwarz, N. (Eds.) Well-Being: The Foundations of Hedonic Psychology; Russell Sage Foundatioin: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Cooke, P.H.; Melchert, T.; Connor, K. Measuring Well-Being: A Review of Instruments. Couns. Psychol. 2016, 44, 730–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lent, R. 2004 Toward a Unifying Theoretical and Practical Perspective on Well-Being and Psychosocial Adjustment. J. Couns. Psychol. 2004, 51, 482–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Suh, E.; Lucas, R.; Smith, H. Subjective Well-Being: Three decades of progress. Psychol. Bull. 1999, 125, 276–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kringelbach, M. The Pleasure Center. Trust Your Animal Instincts; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Berridge, K.; Kringelbach, M. Affective neuroscience of pleasure: Reward in humans and animals. Psychopharmacology 2008, 199, 457–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leknes, S.; Tracey, I. A common neurobiology for pain and pleasure. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2008, 9, 314–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C.; Singer, B. The Contours of Positive Health. Psychol. Inq. 1998, 9, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waterman, A. Two conceptions of happiness: Contrasts of personal expressiveness (eudaimonia) and hedonic enjoyment. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1993, 64, 678–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGregor, I.; Little, B. 1998 Personal projects, happiness, and meaning: On doing well and being yourself. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1998, 74, 494–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waterman, A. Personal expressiveness: Philosophical and psychological foundations. J. Mind Behav. 1990, 11, 47–74. [Google Scholar]

- Waterman, A. The relevance of Aristotle’s conception of eudaimonia for the psychological study of happiness. Theor. Philos. Psychol. 1990, 10, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, B. The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. Am. Psychol. 2001, 56, 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matrone, C.; Brattico, E. The Power of Music on Alzheimer’s Disease and the Need to Understand the Underlying Molecular Mechanisms. JADP 2015, 5, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Taruffi, L.; Pehrs, C.; Skouras, S.; Koelsch, S. Effects of Sad and Happy Music on Mind-Wandering and the Default Mode Network. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 14396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huron, D.; Anderson, N.; Shanahan, D. You can’t play sad music on a banjo: Acoustic factors in the judgment of instrument capacity to convey sadness. Empir. Musicol. Rev. 2014, 9, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachs, M.; Damasio, A.; Habibi, A. The pleasures of sad music: A systematic review. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2015, 9, 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Tol, A.; Edwards, J.; Heflick, N. Sad music as a means for acceptance-based coping. Mus. Sci. 2016, 20, 68–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuoskoski, J.; Eerola, T. Can sad music really make you sad? Indirect measures of affective states induced by music and autobiographical memories. Psychol. Aesthet. Creat. Arts 2012, 6, 204–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alloy, L.; Abramson, L. Judgment of contingency in depressed and nondepressed students: Sadder but wiser? J. Exp. Psychol: Gen. 1979, 108, 441–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clore, G.; Huntsinger, J. How emotions inform judgment and regulate thought. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2007, 11, 393–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storbeck, J.; Clore, G. With sadness comes accuracy; with happiness, false memory: Mood and the false memory effect. Psychol. Sci. 2005, 16, 785–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, J.; Mankowski, T. Self-esteem, mood, and self-evaluation: Changes in mood and the way you see you. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1993, 64, 421–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickinson, A.; Balleine, B. Hedonics: The cognitive-motivational interface. In Pleasures of the Brain; Kringelbach, M., Berridge, K., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2010; pp. 74–84. [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson, B.; Cohn, M.; Coffey, K.; Pek, J.; Finkel, S. Open hearts build lives: Positive emotions, induced through loving-kindness meditation, build consequential personal resources. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2008, 95, 1045–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesse, R. Natural selection and the elusiveness of happiness. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2004, 359, 1333–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brattico, E.; Varankaité, U. Aesthetic empowerment through music. Mus. Sci. 2019, 23, 285–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kringelbach, M.; Berridge, K. The affective core of emotion: Linking pleasure, subjective well-being, and optimal metastability in the brain. Emot. Rev. 2017, 9, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reybrouck, M.; Vuust, P.; Brattico, E. Neural Correlates of Music Listening: Does the Music Matter? Brain Sci. 2021, 11, 1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garrido, S.; Schubert, E. Adaptive and maladaptive attraction to negative emotions in music. Mus. Sci. 2013, 17, 147–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, D.; Claes, M. Music listening, coping, peer affiliation and depression in adolescence. Psychol. Music 2009, 37, 215–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Tol, A.; Edwards, J. Exploring a rationale for choosing to listen when feeling sad. Psychol. Music 2011, 41, 440–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcaro, A.; Huber, R.; Panksepp, J. Behavioral functions of the mesolimbic dopaminergic system: An affective neuroethological perspective. Brain Res. Rev. 2007, 56, 283–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venkatraman, A.; Edlow, B.; Immordino-Yang, M. The Brainstem in Emotion: A Review. Front. Neuroanat. 2017, 11, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsee, C.; Yu, F.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y. Medium maximization. J. Consum. Res. 2003, 30, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnett, J. Sensation seeking: A new conceptualization and a new scale. Pers. Individ. Dif. 1994, 16, 289–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozon, J.; Bensimon, M. Music misuse: A review of the personal and collective roles of “problem music”. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2014, 19, 207–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyman, S.; Malenka, R.; Nestler, E. Neural mechanisms of addiction: The role of reward-related learning and memory. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2006, 29, 565–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard, L.; Gauvin, L.; Raine, K. Ecological models revisited: Their uses and evolution in health promotion over two decades. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2011, 32, 307–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saarikallio, S.; Erkkilä, J. The role of music in adolescents’ mood regulation. Psychol. Music 2007, 35, 88–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zickfeld, J.H.; Schubert, T.W.; Seibt, B.; Blomster, J.K.; Arriaga, P.; Basabe, N.; Blaut, A.; Caballero, A.; Carrera, P.; Dalgar, I.; et al. Kama Muta: Conceptualizing and Measuring the Experience Often labelled Being Moved Across Nations and 15 Languages. Emotion 2019, 19, 402–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Reybrouck, M.; Eerola, T. Musical Enjoyment and Reward: From Hedonic Pleasure to Eudaimonic Listening. Behav. Sci. 2022, 12, 154. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12050154

Reybrouck M, Eerola T. Musical Enjoyment and Reward: From Hedonic Pleasure to Eudaimonic Listening. Behavioral Sciences. 2022; 12(5):154. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12050154

Chicago/Turabian StyleReybrouck, Mark, and Tuomas Eerola. 2022. "Musical Enjoyment and Reward: From Hedonic Pleasure to Eudaimonic Listening" Behavioral Sciences 12, no. 5: 154. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12050154

APA StyleReybrouck, M., & Eerola, T. (2022). Musical Enjoyment and Reward: From Hedonic Pleasure to Eudaimonic Listening. Behavioral Sciences, 12(5), 154. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12050154