Relationship between Mental Disorders and Optimism in a Community-Based Sample of Adults

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Scheier, M.F.; Carver, C.S. Effects of optimism on psychological and physical well-being: Theoretical overview and empirical update. Cogn. Ther. Res. 1992, 16, 201–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carver, C.S.; Scheier, M.F. Discrepancy-Reducing Feedback Processes in Behavior. In On the Self-Regulation of Behavior; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1998; pp. 29–47. [Google Scholar]

- De Ridder, D.; Fournier, M.; Bensing, J. Does optimism affect symptom report in chronic disease? What are its consequences for self-care behaviour and physical functioning? J. Psychosom. Res. 2004, 56, 341–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fournier, M.; de Ridder, D.; Bensing, J. Optimism and adaptation to chronic disease: The role of optimism in relation to self-care options of type 1 diabetes mellitus, rheumatoid arthritis and multiple sclerosis. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2002, 7, 409–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Affleck, G.; Tennen, H.; Zautra, A.; Urrows, S.; Abeles, M.; Karoly, P. Women’s pursuit of personal goals in daily life with fibromyalgia: A value-expectancy analysis. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2001, 69, 587–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaesmer, H.; Rief, W.; Martin, A.; Mewes, R.; Brähler, E.; Zenger, M.; Hinz, A. Psychometric properties and population-based norms of the Life Orientation Test Revised (LOT-R). Br. J. Health Psychol. 2012, 17, 432–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myhren, H.; Ekeberg, Ø.; Tøien, K.; Karlsson, S.; Stokland, O. Posttraumatic stress, anxiety and depression symptoms in patients during the first year post intensive care unit discharge. Crit. Care 2010, 14, R14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Carver, C.S.; Scheier, M.F.; Segerstrom, S.C. Optimism. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2010, 30, 879–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ramsay, J.E.; Yang, F.; Pang, J.S.; Lai, C.M.; Ho, R.C.; Mak, K.K. Divergent pathways to influence: Cognition and behavior differentially mediate the effects of optimism on physical and mental quality of life in Chinese university students. J. Health Psychol. 2015, 20, 963–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Mental Health: Strengthening Our Response; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018; Available online: http://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-health-strengthening-our-response (accessed on 15 September 2019).

- World Health Organization. Mental Health; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019; Available online: http://www.who.int/mental_health/en/ (accessed on 17 September 2019).

- Bilge, U.; Ünlüoğlu, İ.; Yenilmez, Ç. Bir üniversite hastanesi dahiliye polikliniğine başvuran kronik bedensel hastalığı olan hastalarda ruhsal bozuklukların belirlenmesi [Determination of psychiatric disorders among outpatients admitted to the internal medicine clinic in a university hospital]. J. Neurol. Sci. 2012, 29, 316–328. [Google Scholar]

- Keskin, A.; Ünlüoğlu, İ.; Bilge, U.; Yenilmez, Ç. The prevalence of psychiatric disorders distribution of subjects gender and its relationship with psychiatric help-seeking. Noro Psikiyatr. Arsivi 2013, 50, 344–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keskin, A.; Bilge, U. Mental disorders frequency alternative and complementary medicine usage among patients with hypertension and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Niger. J. Clin. Pract. 2014, 17, 717–722. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B.W.; Kroenke, K.; Linzer, M.; deGruy III, F.V.; Hahn, S.R.; Brody, D.; Johnson, J.G. Utility of a new procedure for diagnosing mental disorders in primary care: The PRIME-MD 1000 study. JAMA 1994, 272, 1749–1756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Çorapçıoğlu, A.; Köroğlu, E.; Ceyhun, B.; Doğan, O. Birinci basamak sağlık hizmetlerinde psikiyatrik tanı koydurucu bir ölçeğin (Prime-MD) Türkiye için uyarlanması. Nöropsikiyatri Gündemi 1996, 1, 3–10. [Google Scholar]

- Scheier, M.F.; Carver, C.S. Dispositional optimism and physical well-being: The influence of generalized outcome expectancies on health. J. Personal. 1987, 55, 169–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aydın, G.; Tezer, E. İyimserlik, sağlık sorunları ve akademik başarı ilişkisi. Psikol. Derg. 1991, 7, 2–9. [Google Scholar]

- Ansseau, M.; Dierick, M.; Buntinkx, F.; Cnockaert, P.; De Smedt, J.; Van Den Haute, M.; Vander Mijnsbrugge, D. High prevalence of mental disorders in primary care. J. Affect. Disord. 2004, 78, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canakci, M.E.; Acar, N.; Yenilmez, C.; Ozakin, E.; Kaya, F.B.; Arslan, E.; Caglayan, T.; Dolgun, H. Frequency of Psychiatric Disorders in Nonemergent Admissions to Emergency Department. Niger. J. Clin. Pract. 2019, 22, 208–214. [Google Scholar]

- Van de Velde, S.; Boyd, A.; Villagut, G.; Alonso, J.; Bruffaerts, R.; De Graaf, R.; Florescu, S.; Haro, J.; Kovess-Masfety, V. Gender differences in common mental disorders: A comparison of social risk factors across four European welfare regimes. Eur. J. Public Health 2018, 29, 481–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grandes, G.; Montoya, I.; Arietaleanizbeaskoa, M.S.; Arce, V.; Sanchez, A. The burden of mental disorders in primary care. Eur. Psychiatry 2011, 26, 428–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, V.; Flisher, A.J.; Hetrick, S.; McGorry, P. Mental health of young people: A global public-health Challenge. Lancet 2007, 369, 1302–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drozd, W.; Wojnar, M.; Araszkiewicz, A.; Nawacka-Pawlaczyk, D.; Urbanski, R.; Cwiklinska-Jurkowska, M.; Rybakowski, J. The prevalance of depressive disorders in primary care in Poland. Wiad Lek 2007, 60, 109–113. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, H.; Higgins, E.T. Optimism, promotion pride, and prevention pride as predictors of quality of life. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2003, 29, 1521–1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gustems-Carnicer, J.; Calderón, C.; Santacana, M.F. Psychometric properties of the Life Orientation Test (LOT-R) and its relationship with psychological well-being and academic progress in college students. Rev. Latinoam. Psicol. 2017, 49, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kesebir, S. Depresyon ve somatizasyon. Klin. Psikiyatr. 2004, 1, 14–19. [Google Scholar]

- De Waal, M.W.M.; Arnold, I.A.; Eekhof, J.A.; Van Hemert, A.M. Somatoform disorders in general practice: Prevalence, functional impairment and comorbidity with anxiety and depressive disorders. Br. J. Psychiatry 2004, 184, 470–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- World Health Organization. The World Health Report 2001: Mental Health: New Understanding, New Hope; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Zenger, M.; Brix, C.; Borowski, J.; Stolzenburg, J.U.; Hinz, A. The impact of optimism on anxiety, depression and quality of life in urogenital cancer patients. Psychooncology 2010, 19, 879–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Velden, P.G.; Kleber, R.J.; Fournier, M.; Grievink, L.; Drogendijk, A.; Gersons, B.P. The association between dispositional optimism and mental health problems among disaster victims and a comparison group: A prospective study. J. Affect. Disord. 2007, 102, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szalma, J.L. Individual differences in performance, workload and stress in sustained attention: Optimism and pessimism. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2009, 47, 444–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolcos, S.; Hu, Y.; Iordan, A.D.; Moore, M.; Dolcos, F. Optimism and the brain: Trait optimism mediates the protective role of the orbitofrontal cortex gray matter volume against anxiety. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 2016, 11, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nes, L.S.; Segerstrom, S.C. Dispositional optimism and coping: A meta-analytic review. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2006, 10, 235–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conversano, C.; Rotondo, A.; Lensi, E.; Della Vista, O.; Arpone, F.; Reda, M.A. Optimism and its impact on mental and physical well-being. Clin. Pract. Epidemiol. Ment. Health CP EMH 2010, 6, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giltay, E.J.; Geleijnse, J.M.; Zitman, F.G.; Buijsse, B.; Kromhout, D. Lifestyle and dietary correlates of dispositional optimism in men: The Zutphen Elderly Study. J. Psychosom. Res. 2007, 63, 483–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthony, E.G.; Kritz-Silverstein, D.; Barrett-Connor, E. Optimism and Mortality in Older Men and Women: The Rancho Bernardo Study. J. Aging Res. 2016, 2016, 5185104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Marshall, G.N.; Wortman, C.B.; Kusulas, J.W.; Hervig, L.K.; Vickers, R.R., Jr. Distinguishing optimism from pessimism: Relations to fundamental dimensions of mood and personality. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1992, 62, 1067–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linzer, M.; Spitzer, R.; Kroenke, K.; Williams, J.B.; Hahn, S.; Brody, D.; DeGruy, F. Gender, quality of life, and mental disorders in primary care: Results from the PRIME-MD 1000 study. Am. J. Med. 1996, 101, 526–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Mood Disorder | Anxiety Disorder | Probable Alcohol Abuse | Somatoform Disorder | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (%) * | Yes (%) * | Yes (%) * | Yes (%) * | ||

| Age Group (year) | 24 and below | 11.3 | 2.8 | 4.2 | 2.8 |

| 25–44 | 16.9 | 8.5 ** | 4.2 | 6.5 | |

| 45–64 | 13.5 | 2.9 | 1.4 | 6.2 | |

| 65 and above | 13.2 | 1.5 | 2.9 | 4.4 | |

| p | 0.559 | 0.013 | 0.350 | 0.628 | |

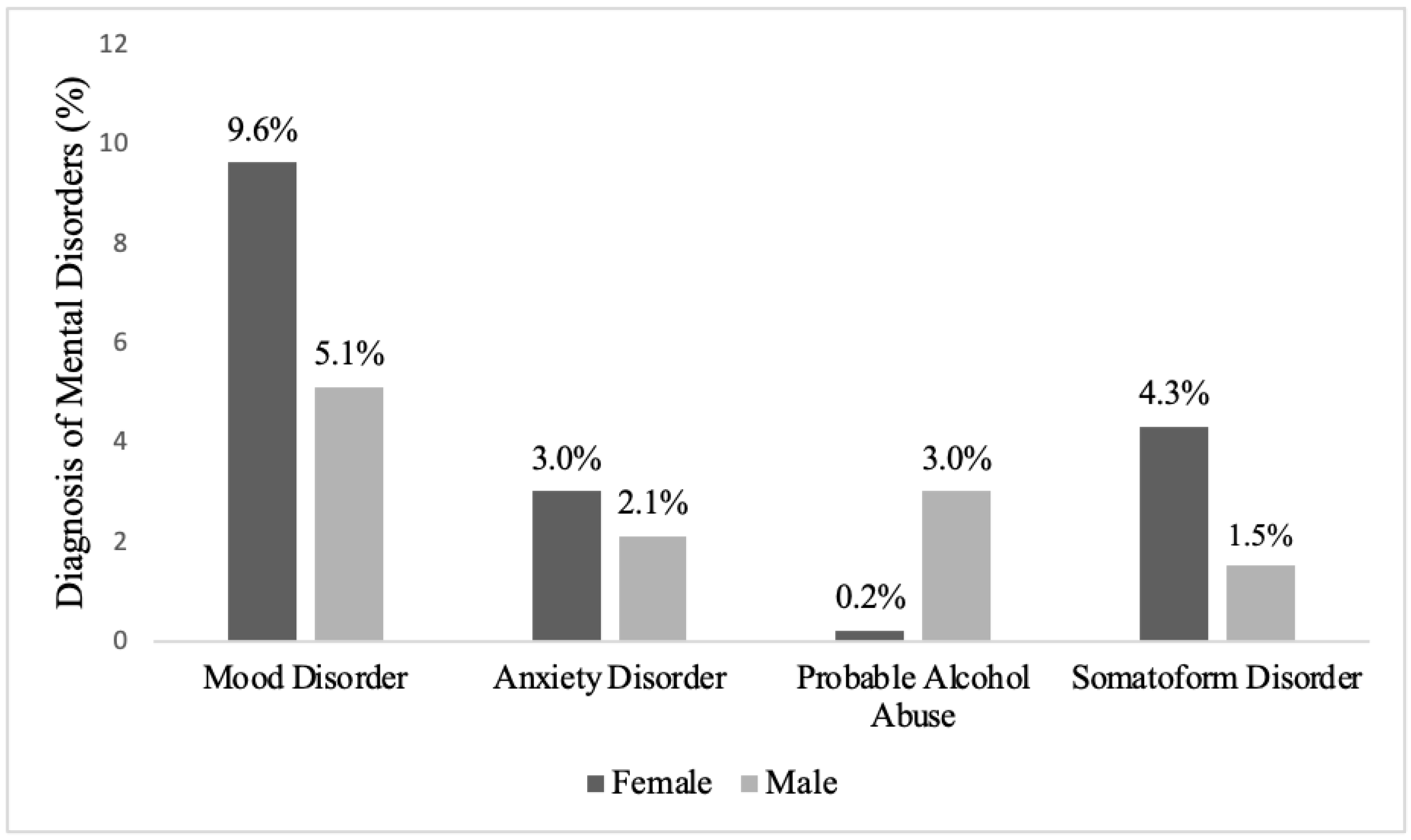

| Sex | Male | 9.3 | 3.9 | 5.4 | 2.7 |

| Female | 21.3 | 6.6 | 0.4 | 9.6 | |

| p | <0.001 | 0.181 | 0.001 | 0.001 | |

| Education Status | Illiterate | 29.8 ** | 8.8 | 0.0 | 10.5 |

| Primary School | 15.9 | 4.5 | 4.1 | 6.6 | |

| High school | 9.0 | 5.5 | 3.4 | 2.8 | |

| University and above | 11.3 | 4.3 | 1.7 | 5.2 | |

| p | 0.001 | 0.572 | 0.309 | 0.159 | |

| Marital status | Married | 13.3 | 5.1 | 2.8 | 5.6 |

| Single | 18.1 | 5.0 | 4.0 | 6.2 | |

| p | 0.127 | 1.000 | 0.623 | 0.910 | |

| Working status | Yes | 9.8 | 4.2 | 2.1 | 3.1 |

| No | 19.0 | 5.9 | 4.0 | 8.1 | |

| p | 0.001 | 0.437 | 0.252 | 0.015 | |

| Income level | Good | 11.2 | 3.4 | 0.0 ** | 2.6 |

| Medium | 12.8 | 4.4 | 3.4 | 6.6 | |

| Poor | 28.6 ** | 10.7 ** | 6.0 | 6.0 | |

| p | <0.001 | 0.039 | 0.023 | 0.256 | |

| Physician-diagnosed chronic illness background | No | 12.6 | 4.0 | 3.5 | 4.8 |

| Yes | 18.6 | 7.1 | 2.4 | 7.6 | |

| p | 0.048 | 0.143 | 0.559 | 0.214 | |

| General Health Status | Good | 7.3 | 3.4 | 2.7 | 4.6 |

| Poor | 29.9 | 8.6 | 4.1 | 8.1 | |

| p | <0.001 | 0.011 | 0.507 | 0.124 | |

| Mental Disorder Group | Life Orientation Test Score | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | Median (Min.–Max.) | |||

| Mood Disorder | Yes | 15.67 ± 4.04 | 15.0 (6.0–26.0) | |

| No | 19.61 ± 4.45 | 20.0 (7.0–31.0) | <0.001 | |

| Anxiety Disorder | Yes | 16.74 ± 3.12 | 17.0 (11.0–23.0) | |

| No | 19.16 ± 4.65 | 19.0 (6.0–31.0) | 0.001 | |

| Probable Alcohol Abuse | Yes | 15.11 ± 3.81 | 15.0 (9.0–24.0) | |

| No | 19.16 ± 4.58 | 19.0 (6.0–31.0) | <0.001 | |

| Somatoform Disorder | Yes | 18.23 ± 4.06 | 19.0 (9.0–26.0) | |

| No | 19.09 ± 4.64 | 19.0 (6.0–31.0) | 0.266 | |

| Mood Disorder OR (%95 CI) | Anxiety Disorder OR (%95 CI) | Probable Alcohol Abuse OR (%95 CI) | Somatoform Disorder OR (%95 CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.63 (0.44–0.91) * | 0.45 (0.27–0.75) ** | 0.71 (0.41–1.24) | 0.99 (0.61–1.61) |

| Gender | 2.59 (1.47–4.53) ** | 1.60 (0.75–3.40) | 0.06 (0.008–0.44) ** | 3.08 (1.35–7.02) ** |

| Education status | 1.31 (0.90–1.90) | 1.03 (0.63–1.70) | ||

| Marital status | 0.78 (0.45–1.37) | |||

| Working status | 0.84 (0.44–1.60) | 1.64 (0.65–4.13) | ||

| Income level | 1.12 (0.67–1.85) | 1.71 (0.86–3.42) | 2.08 (0.87–5.02) | |

| Physician-diagnosed chronic illness background | 1.34 (0.75–2.41) | 2.60 (1.12–6.05) * | ||

| General health status | 3.81 (2.19–6.64) *** | 2.09 (0.92–4.73) | 1.43 (0.67–3.04) | |

| Total score of Life Orientation Test | 0.86 (0.81–0.91) *** | 0.89 (0.83–0.97) ** | 0.83 (0.74–0.93) ** | 0.98 (0.91–1.06) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Öcal, E.E.; Demirtaş, Z.; Atalay, B.I.; Önsüz, M.F.; Işıklı, B.; Metintaş, S.; Yenilmez, Ç. Relationship between Mental Disorders and Optimism in a Community-Based Sample of Adults. Behav. Sci. 2022, 12, 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12020052

Öcal EE, Demirtaş Z, Atalay BI, Önsüz MF, Işıklı B, Metintaş S, Yenilmez Ç. Relationship between Mental Disorders and Optimism in a Community-Based Sample of Adults. Behavioral Sciences. 2022; 12(2):52. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12020052

Chicago/Turabian StyleÖcal, Ece Elif, Zeynep Demirtaş, Burcu Işıktekin Atalay, Muhammed Fatih Önsüz, Burhanettin Işıklı, Selma Metintaş, and Çınar Yenilmez. 2022. "Relationship between Mental Disorders and Optimism in a Community-Based Sample of Adults" Behavioral Sciences 12, no. 2: 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12020052

APA StyleÖcal, E. E., Demirtaş, Z., Atalay, B. I., Önsüz, M. F., Işıklı, B., Metintaş, S., & Yenilmez, Ç. (2022). Relationship between Mental Disorders and Optimism in a Community-Based Sample of Adults. Behavioral Sciences, 12(2), 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12020052