Does Brand Truth-Telling Yield Customer Participation? The Interaction Effects of CSR Strategy and Transparency Signaling

Abstract

1. Introduction

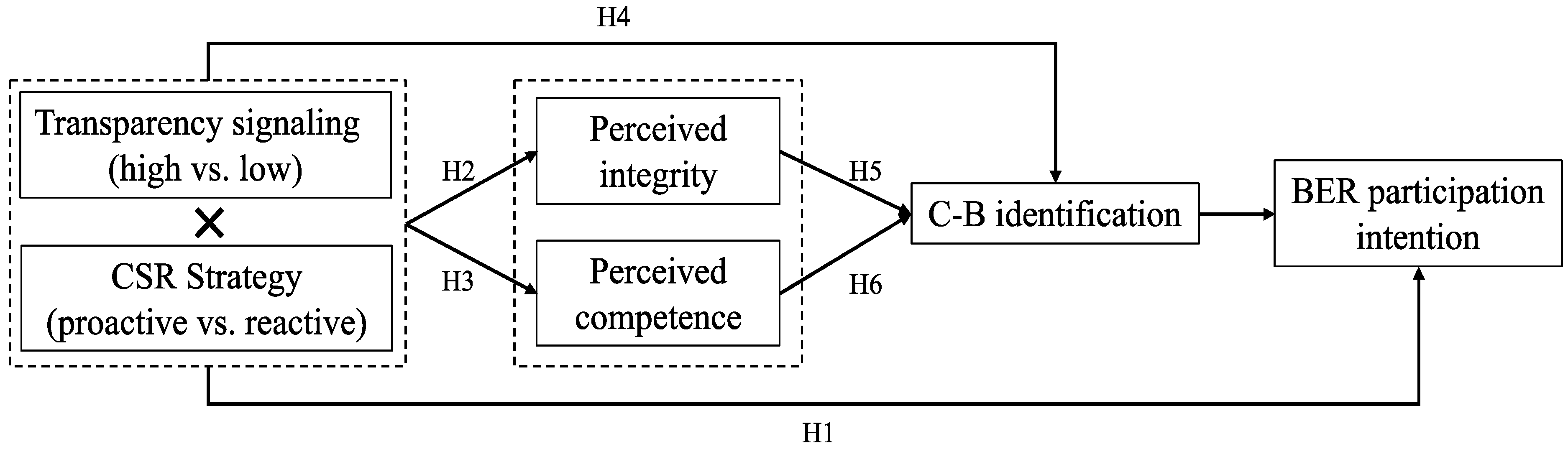

2. Conceptual Background

2.1. Environmental Responsibility in the Food Service Industry

2.2. Managing CSR through Customer Participation

2.3. CSR Communication and Transparency Signaling on Social Media

2.4. Customer Trust

2.5. Customer–Brand Identification

3. Methodology

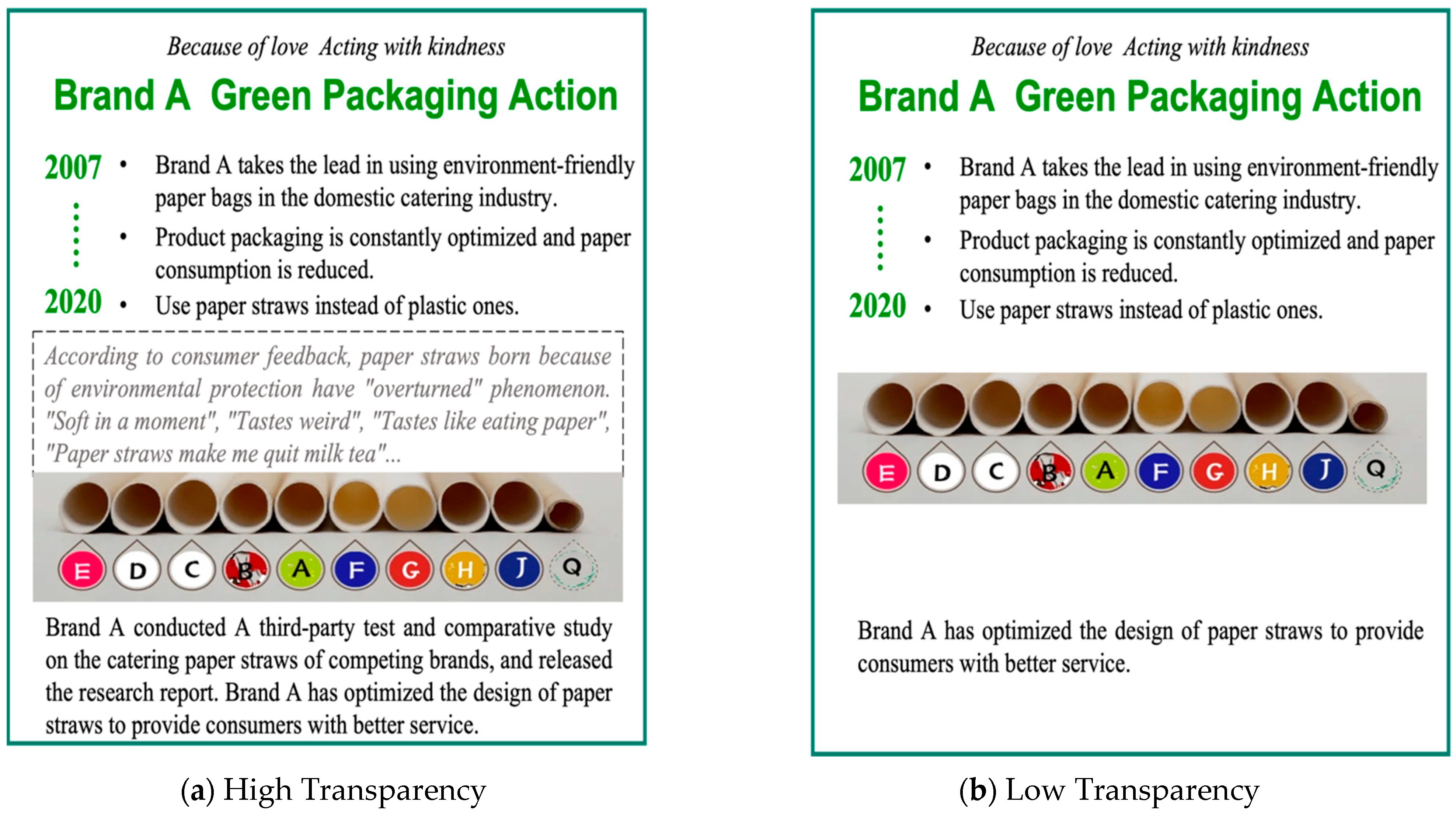

3.1. Stimulus Development and Pilot Test

3.2. Procedures and Instruments

3.3. Data Collection and Analysis Methods

4. Results

4.1. Respondents’ Characteristics

4.2. Manipulation Check

4.3. Hypothesis Test

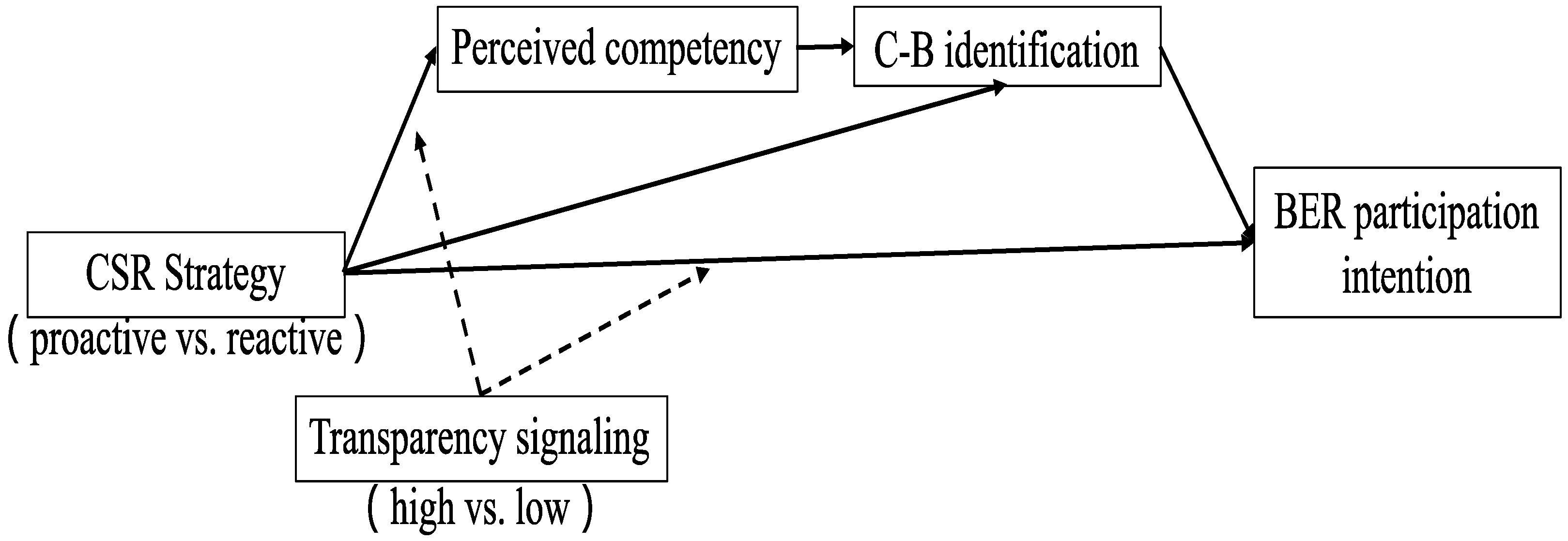

4.3.1. Two-Way Interaction Effects between CSR Strategy and Transparency Signaling

4.3.2. Serial Mediation Analysis

5. Discussion and Conclusion

5.1. Major Findings and Implications

5.2. Theoretical Contributions

5.3. Practical Implications

5.4. Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Sample Stimuli

A.1. Proactive CSR Strategy

A.2. Reactive CSR Strategy

Appendix B. Manipulation Check

B.1. CSR Strategy

- Do you think Brand A is active in social responsibility activities? (Reactive-proactive)

- How voluntary do you think Brand A is to carry out social responsibility activities? (Involuntary-voluntary)

B.2. Transparency Signal

- Brand A offers access to other customers’ comments or rating of its services.

- Brand A compares the pros and cons of its services versus competitors’ offerings.

- Information provided by brand A about its services is not clear.

- The information provided by brand A about its services is easily understood.

References

- Hsiao, T.-Y.; Sung, P.-L.; Tsai, H.-Y.; Wang, T.-S.; Liang, A.R.-D. Establishing a model of low-carbon tour promotion for use by travel agencies from the perspective of shared value theory. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2021, 37, 100787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingeborgrud, L.; Heidenreich, S.; Ryghaug, M.; Skjølsvold, T.M.; Foulds, C.; Robison, R.; Buchmann, K.; Mourik, R. Expanding the scope and implications of energy research: A guide to key themes and concepts from the Social Sciences and Humanities. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2020, 63, 101398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moshood, T.D.; Nawanir, G.; Mahmud, F.; Sorooshian, S.; Adeleke, A.Q. Green and low carbon matters: A systematic review of the past, today, and future on sustainability supply chain management practices among manufacturing industry. Clean. Eng. Technol. 2021, 4, 100144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilal, F.G.; Channa, N.A.; Gilal, N.G.; Gilal, R.G.; Gong, Z.; Zhang, N. Corporate social responsibility and brand passion among consumers: Theory and evidence. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 2275–2285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosta, M.; Zabkar, V. Antecedents of Environmentally and Socially Responsible Sustainable Consumer Behavior. J. Bus. Ethics 2020, 171, 273–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ianole-Calin, R.; Druica, E.; Hubona, G.; Wu, B. What drives Generations Y and Z towards collaborative consumption adoption? Evidence from a post-communist environment. Kybernetes 2020, 50, 1449–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Liu, S.; Li, H.; Yang, Z.; Liang, S.; Deng, N. Q1-7.2-Love of nature as a mediator between connectedness to nature and sustainable consumption behavior. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 242, 118451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohr, L.A.; Webb, D.J. The effects of corporate social responsibility and price on consumer responses. J. Consum. Aff. 2005, 39, 121–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Wong, C.W.Y.; Miao, X. Analysis of the trend in the knowledge of environmental responsibility research. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 278, 123402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregori, P.; Holzmann, P. Digital sustainable entrepreneurship: A business model perspective on embedding digital technologies for social and environmental value creation. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 272, 122817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, A.M.; Green, T.; Brady, M.K.; Peloza, J. Can corporate social responsibility deter consumer dysfunctional behavior? J. Consum. Mark. 2020, 37, 729–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratnakaran, S.T.; Edward, M. Evaluating cause-marketing campaigns in the Indian corporate landscape: The role of consumer skepticism and consumer attributions of firm’s motive. Int. J. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Mark. 2019, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connelly, B.L.; Certo, S.T.; Ireland, R.D.; Reutzel, C.R. Signaling Theory: A Review and Assessment. J. Manag. 2011, 37, 39–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, M. Job Market Signaling. Q. J. Econ. 1973, 87, 355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker-Olsen, K.L.; Cudmore, B.A.; Hill, R.P. The impact of perceived corporate social responsibility on consumer behavior. J. Bus. Res. 2006, 59, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huarng, K.-H.; Botella-Carrubi, D.; Yu, T.H.-K. The effect of technology, information, and marketing on an interconnected world. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 129, 314–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Yin, X.; Lee, G. The effect of CSR on corporate image, customer citizenship behaviors, and customers’ long-term relationship orientation. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 88, 102520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verk, N.; Golob, U.; Podnar, K. A Dynamic Review of the Emergence of Corporate Social Responsibility Communication. J. Bus. Ethics 2021, 168, 491–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oncioiu, I.; Căpușneanu, S.; Topor, D.; Tamaș, A.; Solomon, A.-G.; Dănescu, T. Fundamental Power of Social Media Interactions for Building a Brand and Customer Relations. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2021, 16, 1702–1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcaide González, M.Á.; De La Poza Plaza, E.; Guadalajara Olmeda, N. The impact of corporate social responsibility transparency on the financial performance, brand value, and sustainability level of IT companies. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 642–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.; Ha, M. Corporate social responsibility and earnings transparency: Evidence from Korea. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 1498–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubbink, W.; Graafland, J.; van Liedekerke, L. CSR, Transparency and the Role of Intermediate Organisations. J. Bus. Ethics 2008, 82, 391–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.H.; Comello, M.L. (Nori) G. Transparency and Industry Stigmatization in Strategic CSR Communication. Manag. Commun. Q. 2019, 33, 68–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhaduri, G.; Copeland, L. Going green? How skepticism and information transparency influence consumers’ brand evaluations for familiar and unfamiliar brands. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. Int. J. 2020, 25, 80–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Eisingerich, A.B.; Auh, S.; Merlo, O.; Chun, H.E.H. Service Firm Performance Transparency: How, When, and Why Does It Pay Off? J. Serv. Res. 2015, 18, 451–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Duan, Z.; Du, M.; Miao, X. A Comprehensive Knowledge Pedigreeon Environmental Transparency. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2020, 30, 535–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-González, S.; Bande, B.; Fernández-Ferrín, P.; Kimura, T. Corporate social responsibility and consumer advocacy behaviors: The importance of emotions and moral virtues. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 231, 846–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tafjel, H.; Turner, J.C. An Integrative Theory of Intergroup Conflict. In The Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations; Brooks/Cole: Monterey, CA, USA, 1979; Volume 33. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, J.; Hogg, M.; Oakes, P.; Reicher, S.; Wetherell, M. Rediscovering the Social Group: A Self-Categorization Theory; Basil Blackwell: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Abrams, D.; Hogg, M.A. Social Identification, Self-Categorization and Social Influence. Eur. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 1990, 1, 195–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stets, J.E.; Burke, P.J. Identity Theory and Social Identity Theory. Soc. Psychol. Q. 2000, 63, 224–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taşdemir, N. The Relationships between Motivations of Intergroup Differentiation as a Function of Different Dimensions of Social Identity. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2011, 15, 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajfel, H.; Turner, J. The Social Identity Theory of Inter-Group Behavior. In The Psychology of Intergroup Relations; Nelson-Hall: Chicago, IL, USA, 1986; Volume 13, p. 7. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.W.; Kim, Y.M.; Kim, Y.E. Antecedents of Adopting Corporate Environmental Responsibility and Green Practices. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 148, 397–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, M.; Qu, Y.; Zafar, A.U.; Ding, X.; Rehman, S.U. Translating stakeholders’ pressure into environmental practices–The mediating role of knowledge management. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 275, 124163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, B.; Wen, J. Online corporate social responsibility communication strategies and stakeholder engagements: A comparison of controversial versus noncontroversial industries. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 881–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amor-Esteban, V.; Galindo-Villardón, M.-P.; García-Sánchez, I.-M.; David, F. An extension of the industrial corporate social responsibility practices index: New information for stakeholder engagement under a multivariate approach. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 26, 127–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.; Xiao, X. Voluntary Engagement in Environmental Projects: Evidence from Environmental Violators. J. Bus. Ethics 2020, 164, 325–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Zou, F.; Zhang, P. The role of innovation for performance improvement through corporate social responsibility practices among small and medium-sized suppliers in China. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 26, 341–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anser, M.K.; Yousaf, Z.; Majid, A.; Yasir, M. Does corporate social responsibility commitment and participation predict environmental and social performance? Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 2578–2587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breeze, B.; Wiepking, P. Different Drivers: Exploring Employee Involvement in Corporate Philanthropy. J. Bus. Ethics 2020, 165, 453–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hur, W.; Moon, T.; Kim, H. When and how does customer engagement in CSR initiatives lead to greater CSR participation? The role of CSR credibility and customer–company identification. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 1878–1891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Liu, C. Takeaway food consumption and its geographies of responsibility in urban Guangzhou. Food Cult. Soc. 2021, 25, 354–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Harris, L. The impact of Covid-19 pandemic on corporate social responsibility and marketing philosophy. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 116, 176–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matten, D.; Moon, J. Reflections on the 2018 Decade Award: The Meaning and Dynamics of Corporate Social Responsibility. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2020, 45, 7–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, L.; Han, T.; Chu, H.; Xia, B. Behavior Selection of Stakeholders toward Megaproject Social Responsibility: Perspective from Social Action Theory. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.-C. Corporate social responsibility on customer behaviour: The mediating role of corporate image and customer satisfaction. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excell. 2020, 31, 742–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, C.; Germann, F.; Grewal, R. Washing Away Your Sins? Corporate Social Responsibility, Corporate Social Irresponsibility, and Firm Performance. J. Mark. 2016, 80, 59–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, W.; Song, B. The interplay between post-crisis response strategy and pre-crisis corporate associations in the context of CSR crises. Public Relat. Rev. 2020, 46, 101883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chathoth, P.K.; Ungson, G.R.; Harrington, R.J.; Chan, E.S.W. Co-creation and higher order customer engagement in hospitality and tourism services: A critical review. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 28, 222–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groth, M. Customers as Good Soldiers: Examining Citizenship Behaviors in Internet Service Deliveries. J. Manag. 2005, 31, 7–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Tang, L.; Fiore, A.M. Enhancing consumer–brand relationships on restaurant Facebook fan pages: Maximizing consumer benefits and increasing active participation. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 36, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Jain, K.; Kingshott, R.P.J.; Ueno, A. Customer engagement and relationships in multi-actor service ecosystems. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 121, 487–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J. The effectiveness of nutritional information on foodservice companies’ corporate social responsibility. Asia Pac. Bus. Rev. 2017, 23, 44–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerro, M.; Raimondo, M.; Stanco, M.; Nazzaro, C.; Marotta, G. Cause Related Marketing among Millennial Consumers: The Role of Trust and Loyalty in the Food Industry. Sustainability 2019, 11, 535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, L.W.; Goll, I.; Rasheed, A.A.; Crawford, W.S. Nonmarket Responses to Regulation: A Signaling Theory Approach. Group Organ. Manag. 2020, 45, 865–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taj, S.A. Application of signaling theory in management research: Addressing major gaps in theory. Eur. Manag. J. 2016, 34, 338–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogunfowora, B.; Stackhouse, M.; Oh, W.-Y. Media Depictions of CEO Ethics and Stakeholder Support of CSR Initiatives: The Mediating Roles of CSR Motive Attributions and Cynicism. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 150, 525–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, W.; Peng, M.W.; Tan, W.; Cheung, Y.-L. The Signaling Effect of Corporate Social Responsibility in Emerging Economies. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 134, 479–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chia, A.; Kern, M.L.; Neville, B.A. CSR for Happiness: Corporate determinants of societal happiness as social responsibility. Bus. Ethics A Eur. Rev. 2020, 29, 422–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostertag, F.; Hahn, R.; Ince, I. Blended value co-creation: A qualitative investigation of relationship designs of social enterprises. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 129, 428–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beldad, A.D.; Seijdel, C.T.; de Jong, M.D.T. Managing Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Together: The Effects of Stakeholder Participation and Third-Party Organization (TPO) Endorsement on CSR Initiative Effectiveness. Corp. Reput. Rev. 2020, 23, 225–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handa, M.; Gupta, S. Digital cause-related marketing campaigns: Relationship between brand-cause fit and behavioural intentions. J. Indian Bus. Res. 2020, 12, 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Liao, G.; Albitar, K. Does corporate environmental responsibility engagement affect firm value? The mediating role of corporate innovation. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2020, 29, 1045–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felix, R.; Rauschnabel, P.A.; Hinsch, C. Elements of strategic social media marketing: A holistic framework. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 70, 118–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y.G.; Tao, W.; Rim, H. Theoretical Insights of CSR Research in Communication from 1980 to 2018: A Bibliometric Network Analysis. J. Bus. Ethics 2022, 177, 327–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kietzmann, J.H.; Hermkens, K.; McCarthy, I.P.; Silvestre, B.S. Social media? Get serious! Understanding the functional building blocks of social media. Bus. Horiz. 2011, 54, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulianne, S. Revolution in the making? Social media effects across the globe. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2019, 22, 39–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapp, A.; Beitelspacher, L.S.; Grewal, D.; Hughes, D.E. Understanding social media effects across seller, retailer, and consumer interactions. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2013, 41, 547–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxton, G.D.; Gomez, L.; Ngoh, Z.; Lin, Y.-P.; Dietrich, S. Do CSR Messages Resonate? Examining Public Reactions to Firms’ CSR Efforts on Social Media. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 155, 359–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heikkurinen, P.; Forsman-Hugg, S. Strategic Corporate Responsibility in the Food Chain. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2011, 18, 306–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, S.; Bhattacharya, C.B.; Sen, S. Reaping relational rewards from corporate social responsibility: The role of competitive positioning. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2007, 24, 224–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, T.; Lutz, R.J.; Weitz, B.A. Corporate Hypocrisy: Overcoming the Threat of Inconsistent Corporate Social Responsibility Perceptions. J. Mark. 2009, 73, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rim, H.; Swenson, R.; Anderson, B. What happens when brands tell the truth? Exploring the effects of transparency signaling on corporate reputation for agribusiness. J. Appl. Commun. Res. 2019, 47, 439–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, K. Information Transparency of Business-to-Business Electronic Markets: A Game-Theoretic Analysis. Manag. Sci. 2004, 50, 670–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eggert, A.; Helm, S. Exploring the impact of relationship transparency on business relationships. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2003, 32, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cambier, F.; Poncin, I. Inferring brand integrity from marketing communications: The effects of brand transparency signals in a consumer empowerment context. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 109, 260–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinberg, M.; Liu, Y.; Huang, X.; Eisingerich, A.B. A Bad Job of Doing Good: Does Corporate Transparency on a Country and Company Level Moderate Corporate Social Responsibility Effectiveness? J. Int. Mark. 2021, 29, 2–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, N.L.; Kim, G.; Rothenberg, L. Is Honesty the Best Policy? Examining the Role of Price and Production Transparency in Fashion Marketing. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Zhang, K.; Xie, J. Bad Greenwashing, Good Greenwashing: Corporate Social Responsibility and Information Transparency. Manag. Sci. 2020, 66, 3095–3112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopp, T.; Fisher, J. A psychological model of transparent communication effectiveness. Corp. Commun. Int. J. 2020, 26, 403–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Bouman, T.; Perlaviciute, G.; Steg, L. Effects of competence- and integrity-based trust on public acceptability of renewable energy projects in China and the Netherlands. J. Environ. Psychol. 2020, 67, 101390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connelly, B.L.; Crook, T.R.; Combs, J.G.; Ketchen, D.J.; Aguinis, H. Competence- and Integrity-Based Trust in Interorganizational Relationships: Which Matters More? J. Manag. 2018, 44, 919–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.D.; Cenfetelli, R.T.; Aquino, K. Do different kinds of trust matter? An examination of the three trusting beliefs on satisfaction and purchase behavior in the buyer–seller context. J. Strateg. Inf. Syst. 2016, 25, 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terwel, B.W.; Harinck, F.; Ellemers, N.; Daamen, D.D.L. Competence-Based and Integrity-Based Trust as Predictors of Acceptance of Carbon Dioxide Capture and Storage (CCS). Risk Anal. 2009, 29, 1129–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, C.-P. To Share or Not to Share: Modeling Tacit Knowledge Sharing, Its Mediators and Antecedents. J. Bus. Ethics 2007, 70, 411–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, V.T.; Nguyen, N.; Wang, J. Consumers’ perceptions and responses towards online retailers’ CSR. Int. J. Retail. Distrib. Manag. 2020, 48, 1277–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, S.K.; Ahearne, M.; Mullins, R.; Hayati, B.; Schillewaert, N. Exploring the dynamics of antecedents to consumer–Brand identification with a new brand. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2013, 41, 234–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuah, S.H.-W.; El-Manstrly, D.; Tseng, M.-L.; Ramayah, T. Sustaining customer engagement behavior through corporate social responsibility: The roles of environmental concern and green trust. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 262, 121348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Polonsky, M.J. In-store experience quality and perceived credibility: A green retailer context. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 49, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, J.; Zhou, Z.; Zhang, L.; Majeed, S. Do Brand Competence and Warmth Always Influence Purchase Intention? The Moderating Role of Gender. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, C.; Bagozzi, R.P.; Grønhaug, K. The impact of corporate social responsibility on consumer brand advocacy: The role of moral emotions, attitudes, and individual differences. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 95, 514–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hur, W.-M.; Moon, T.-W.; Kim, H. When does customer CSR perception lead to customer extra-role behaviors? The roles of customer spirituality and emotional brand attachment. J. Brand Manag. 2020, 27, 421–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.Y.; Zhang, W.; Abitbol, A. What Makes CSR Communication Lead to CSR Participation? Testing the Mediating Effects of CSR Associations, CSR Credibility, and Organization–Public Relationships. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 157, 413–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mael, F.; Ashforth, B.E. Alumni and their alma mater: A partial test of the reformulated model of organizational identification. J. Organ. Behav. 1992, 13, 103–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaker, J.; Vohs, K.D.; Mogilner, C. Nonprofits Are Seen as Warm and For-Profits as Competent: Firm Stereotypes Matter. J. Consum. Res. 2010, 37, 224–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2014; Volume 51, pp. 335–337. ISBN 9781462549030. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic and Resampling Strategies for Assessing and Comparing Indirect Effects in Multiple Mediator Models. Behav. Res. Methods 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakaria, M.; Aoun, C.; Liginlal, D. Objective Sustainability Assessment in the Digital Economy: An Information Entropy Measure of Transparency in Corporate Sustainability Reporting. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilal, F.G.; Paul, J.; Gilal, N.G.; Gilal, R.G. Strategic CSR-brand Fit and Customers’ Brand Passion: Theoretical Extension and Analysis. Psychol. Mark. 2021, 38, 759–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, K.; Harness, D. Whose Voice Is Heard? The Influence of User-Generated versus Company-Generated Content on Consumer Scepticism towards CSR. J. Mark. Manag. 2019, 35, 886–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morhart, F.; Malär, L.; Guèvremont, A.; Girardin, F.; Grohmann, B. Brand Authenticity: An Integrative Framework and Measurement Scale. J. Consum. Psychol. 2015, 25, 200–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, S.-J.; Hwang, H. What Makes Consumers Respond to Creating Shared Value Strategy? Considering Consumers as Stakeholders in Sustainable Development. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 26, 388–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreejesh, S.; Sarkar, J.G.; Sarkar, A. CSR through Social Media: Examining the Intervening Factors. MIP 2019, 38, 103–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einwiller, S.; Lis, B.; Ruppel, C.; Sen, S. When CSR-Based Identification Backfires: Testing the Effects of CSR-Related Negative Publicity. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 104, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, A.; Frow, P.; Steinhoff, L.; Eggert, A. Toward a Comprehensive Framework of Value Proposition Development: From Strategy to Implementation. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2020, 87, 244–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foscht, T.; Lin, Y.; Eisingerich, A.B. Blinds up or down? The Influence of Transparency, Future Orientation, and CSR on Sustainable and Responsible Behavior. Eur. J. Mark. 2018, 52, 476–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghadge, A.; Kaklamanou, M.; Choudhary, S.; Bourlakis, M. Implementing Environmental Practices within the Greek Dairy Supply Chain: Drivers and Barriers for SMEs. IMDS 2017, 117, 1995–2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, Y.; Lee, J. The Effect of Participation Effort on CSR Participation Intention: The Moderating Role of Construal Level on Consumer Perception of Warm Glow and Perceived Costs. Sustainability 2019, 12, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Measures and Items (7-Point Likert Scales) | Factor Loading | Cronbach’s α | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived integrity (PI) | ||||

| - This brand treats people like me fairly and justly | 0.802 *** | 0.908 | 0.911 | 0.72 |

| - Whenever this brand makes an important decision, I know it will be concerned about people like me | 0.886 *** | |||

| - Sound principles seem to guide this brand’s behavior | 0.892 *** | |||

| - This brand does not mislead people like me | 0.804 *** | |||

| Perceived competence (PC) | ||||

| - I feel very confident about this brand’s skills | 0.854 *** | 0.895 | 0.899 | 0.748 |

| - This brand can accomplish what it says it will do | 0.919 *** | |||

| - This brand is known to be successful at the things it tries to do | 0.817 *** | |||

| Customer-Brand identification (CBI) | ||||

| - When someone criticizes this brand, it feels like a personal insult. | 0.788 *** | 0.922 | 0.926 | 0.759 |

| - When I talk about this brand, I usually say “we” rather than “they.” | 0.905 *** | |||

| - This brand’s successes are my successes. | 0.928 *** | |||

| - When someone praises this brand, it feels like a personal compliment. | 0.849 *** | |||

| BER participation intention (BPI) | ||||

| - It’s probable that I will be involved in the brand’s environmental services programs | 0.846 *** | 0.924 | 0.924 | 0.753 |

| - My involvement in the brand’s environmental services programs is likely | 0.837 *** | |||

| - I am willing to get involved in the brand’s environmental services programs | 0.913 *** | |||

| - I would consider getting involved in the brand’s environmental services programs | 0.873 *** |

| PI | PC | CBI | BPI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived integrity (PI) | 0.849 | |||

| Perceived competence (PC) | 0.597 ** | 0.865 | ||

| Customer-Band identification (CBI) | 0.653 ** | 0.691 ** | 0.871 | |

| BER participation intention (BPI) | 0.273 ** | 0.298 ** | 0.205 * | 0.868 |

| CSR Strategy | Transparency Signal | Perceived Integrity | Perceived Competence | CBI | BER Participation Intention | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | ||

| Proactive | High | 5.55 | 0.88 | 5.48 | 1.23 | 5.23 | 0.83 | 5.65 | 0.73 |

| Low | 4.26 | 1.32 | 4.73 | 1.43 | 4.87 | 1.6 | 4.64 | 1.62 | |

| Reactive | High | 5.63 | 1.03 | 4.95 | 1.46 | 4.85 | 1.49 | 3.53 | 1.42 |

| Low | 4.03 | 1.12 | 4.49 | 1.27 | 4.51 | 1.45 | 3.68 | 1.5 | |

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 75 | 53.57% |

| Female | 65 | 46.43% |

| Age | ||

| Younger than age 18 years | 5 | 3.57% |

| 18~25 years | 22 | 15.71% |

| 26~30 years | 31 | 22.14% |

| 31~40 years | 35 | 25.00% |

| 41~50 years | 29 | 20.71% |

| 51~60 years | 14 | 10.00% |

| Over than age of 60 years | 4 | 2.86% |

| Perceived Integrity | Perceived Competence | CBI | BER Participation Intention | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Main effect | ||||

| CSR Strategy (CS) | 0.164 ** | 2.78 ** | 1742.48 ** | 28.32 ** |

| Transparency signaling (TS) | 60.375 *** | 6.89 | 2.49 | 10.36 |

| Interaction effect | ||||

| CS * TS | 0.753 * | 0.39 * | 0.002 | 0.138 ** |

| Verification | H2 Accepted | H3 Accepted | H4 Rejected | H1 Accepted |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yu, W.; Zhou, J.; He, M.; Si, D. Does Brand Truth-Telling Yield Customer Participation? The Interaction Effects of CSR Strategy and Transparency Signaling. Behav. Sci. 2022, 12, 514. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12120514

Yu W, Zhou J, He M, Si D. Does Brand Truth-Telling Yield Customer Participation? The Interaction Effects of CSR Strategy and Transparency Signaling. Behavioral Sciences. 2022; 12(12):514. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12120514

Chicago/Turabian StyleYu, Weiping, Jun Zhou, Mingli He, and Dongyang Si. 2022. "Does Brand Truth-Telling Yield Customer Participation? The Interaction Effects of CSR Strategy and Transparency Signaling" Behavioral Sciences 12, no. 12: 514. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12120514

APA StyleYu, W., Zhou, J., He, M., & Si, D. (2022). Does Brand Truth-Telling Yield Customer Participation? The Interaction Effects of CSR Strategy and Transparency Signaling. Behavioral Sciences, 12(12), 514. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12120514