Workplace Incivility and Employee Performance: Does Trust in Supervisors Matter? (A Dual Theory Perspective)

Abstract

:1. Introduction

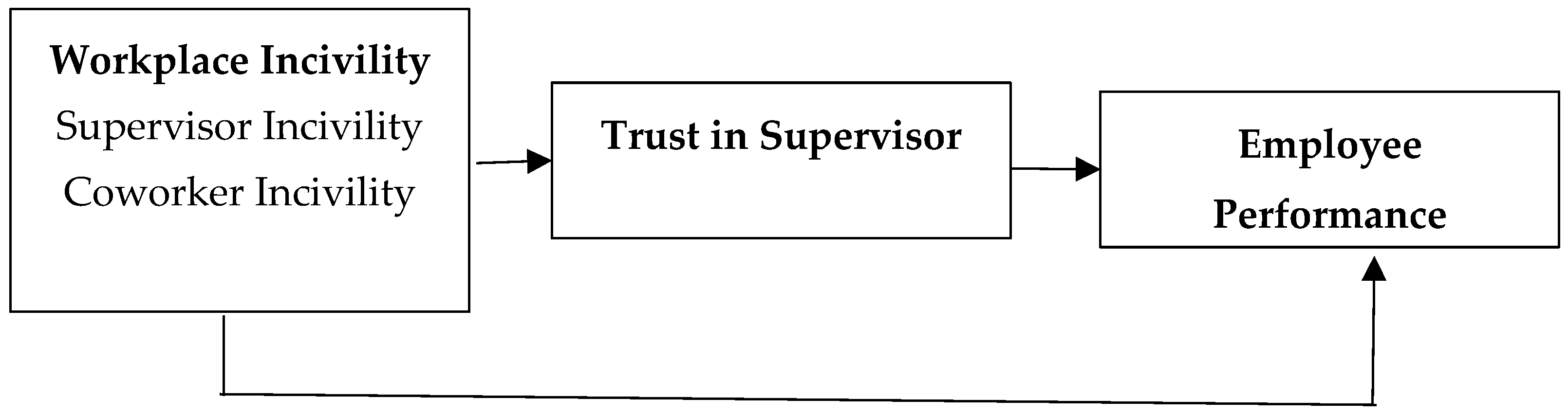

2. Theory and Hypotheses

2.1. Conservation of Resources Theory

2.2. Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs Theory

2.3. Workplace Incivility and Employee Performance

2.4. Workplace Incivility and Trust in Supervisors

2.5. Trust in Supervisors and Employee Performance

3. Methodology

Population and Sampling

4. Results

4.1. Demographic Information

4.2. Measurement Model

4.3. Structural Model

4.4. Robustness (Nonlinear Effects)

5. Discussion

5.1. Implications and Suggestions

5.2. Limitations and Future Directions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Questionnaire

| S# | Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Neutral | Agree | Strongly Agree | |

| 1 | Workplace Incivility (Cortina, L.M., Magley, V.J., Williams, J.H., & Langhout, R.D. (2001). Incivility in the workplace: Incidence and Impact. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 6(1), 64–80.) [24] | |||||

| A | Uncivil behavior from supervisors | |||||

| WI1 | Your supervisor puts you down during at work. | -1- | -2- | -3- | -4- | -5- |

| WI2 | Your supervisor pays little attention to your statements or shows little interest in your opinions. | -1- | -2- | -3- | -4- | -5- |

| WI3 | Your supervisor makes demeaning or derogatory remarks about you. | -1- | -2- | -3- | -4- | -5- |

| WI4 | Your supervisor addresses you in unprofessional terms, either publicly or privately. | -1- | -2- | -3- | -4- | -5- |

| WI5 | Your supervisor ignores or excludes you during meetings, etc. | -1- | -2- | -3- | -4- | -5- |

| WI6 | Your supervisor doubts your judgment on matters for which you have responsibility. | -1- | -2- | -3- | -4- | -5- |

| WI7 | Your supervisor makes unwanted attempts to draw you into discussions of personal matters. | -1- | -2- | -3- | -4- | -5- |

| B | Uncivil behavior from coworkers | |||||

| WI8 | Your coworkers put you down or are condescending to you. | -1- | -2- | -3- | -4- | -5- |

| WI9 | Your coworkers pay little attention to your statements or show little interest in your opinion. | -1- | -2- | -3- | -4- | -5- |

| WI10 | Your coworkers make demeaning or derogatory remarks about you. | -1- | -2- | -3- | -4- | -5- |

| WI11 | Your coworkers address you in unprofessional terms, either publicly or privately. | -1- | -2- | -3- | -4- | -5- |

| WI12 | Your coworkers ignore or exclude you. | -1- | -2- | -3- | -4- | -5- |

| WI13 | Your coworkers doubt your judgment on matters for which you have responsibility. | -1- | -2- | -3- | -4- | -5- |

| WI14 | Your coworkers make unwanted attempts to draw you into discussions of personal matters. | -1- | -2- | -3- | -4- | -5- |

| 2 | Employee Performance Griffin, M. A., Neal, A., Parker, S. K., (2007), A new model of work role performance: Positive behavior in uncertain and interdependent contexts. Academy of Management Journal, 50(2), 327–347. [44] | |||||

| A | Individual task proficiency | |||||

| EP1 | Carried out the core parts of your job well. | -1- | -2- | -3- | -4- | -5- |

| EP2 | Completed your core tasks well using the standard procedures. | -1- | -2- | -3- | -4- | -5- |

| EP3 | Ensured your tasks were completed properly. | -1- | -2- | -3- | -4- | -5- |

| B | Individual task adaptivity | |||||

| EP4 | Adapted well to changes in core tasks. | -1- | -2- | -3- | -4- | -5- |

| EP5 | Coped with changes to the way you have to do your core tasks. | -1- | -2- | -3- | -4- | -5- |

| EP6 | Learned new skills to help you adapt to changes in your core tasks. | -1- | -2- | -3- | -4- | -5- |

| EP7 | Individual task proactivity. | |||||

| EP8 | Initiated better ways of doing your core tasks. | -1- | -2- | -3- | -4- | -5- |

| EP9 | Came up with ideas to improve the way in which your core tasks are done. | -1- | -2- | -3- | -4- | -5- |

| EP10 | Made changes to the way your core tasks are done. | -1- | -2- | -3- | -4- | -5- |

| Trust in supervisors questionnaire Reference: Mcallister, D.J. (1995). Affect and Cognitive Based Trust As foundations for Interpersonal Cooperation In Organizations. Academy of management Journal, 38(1), 24–59. [45] | ||||||

| TS1: | My manager/supervisor performs his/her job with professionalism and dedication. | -1- | -2- | -3- | -4- | -5- |

| TS2: | Given my manager’s/supervisor’s track record, I see no reason to doubt his/her competence and preparation for the job. | -1- | -2- | -3- | -4- | -5- |

| TS3: | I can rely on my manager/supervisor not to make my job more difficult by his careless work. | -1- | -2- | -3- | -4- | -5- |

| TS4: | Most people, even those who are not close friends of my manager/supervisor, trust and respect him/her as a coworker. | -1- | -2- | -3- | -4- | -5- |

| TS5: | My coworkers, who interact with my manager/supervisor, consider him/her to be trustworthy. | -1- | -2- | -3- | -4- | -5- |

| TS6: | If people knew more about my manager’s/supervisor’s background, they would be more concerned and monitor his/her performance more closely. | -1- | -2- | -3- | -4- | -5- |

| TS7: | My manager/supervisor and I have a sharing relationship. We can both freely share our ideas, feelings, and hopes. | -1- | -2- | -3- | -4- | -5- |

| TS8: | I can talk freely to my manager/supervisor about difficulties I am having at work and know that (s)he will want to listen. | -1- | -2- | -3- | -4- | -5- |

| TS9: | My manager/supervisor and I would both feel a sense of loss if one of us were transferred and we could no longer work together. | -1- | -2- | -3- | -4- | -5- |

| TS10: | If I shared my problems with my manager/supervisor, I know (s)he would respond constructively and caringly. | -1- | -2- | -3- | -4- | -5- |

| TS11: | I would have to say that my manager/supervisor and I have both made considerable emotional investments in our working relationship. | -1- | -2- | -3- | -4- | -5- |

References

- Andersson, L.M.; Pearson, C.M. Tit for tat? The spiraling effect of incivility in the Workplace. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1999, 24, 452–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasconcelos, A.F. Workplace incivility: A literature review. Int. J. Work. Health Manag. 2020, 13, 513–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulton, C. The pleasure principle: The power of positive affect in information Seeking. Aslib. Proc. 2009, 61, 245–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, F.; Nolan, J. Performance appraisal in Western and local banks in China: The influence of firm ownership on the perceived importance of Guanxi. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2017, 28, 1433–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appelbaum, S.H.; Iaconi, G.D.; Matousek, A. Positive and negative deviant workplace behaviors: Causes, impacts, and solutions. Corp. Gov. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2007, 7, 586–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foulk, T.; Woolum, A.; Erez, A. Catching rudeness is like catching a cold: The contagion effects of low-intensity negative behaviors. J. Appl. Psychol. 2016, 101, 50–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Arshad, R.; Ismail, I.R. Workplace incivility and knowledge hiding behavior: Does personality matter? J. Organ. Eff. People Perform. 2018, 5, 278–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jawahar, I.M.; Schreurs, B. Supervisor incivility and how it affects subordinates’ performance: A matter of trust. Perso. Rev. 2018, 47, 709–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, N.; Singh, V.K. Effect of workplace incivility on job satisfaction and turnover intentions in India. South Asian J. Glob. Bus. Res. 2016, 5, 234–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schilpzand, P.; De Pater, I.E.; Erez, A. Workplace incivility: A review of the literature and agenda for future research. J. Organ. Behav. 2016, 37, 57–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atatsi, E.A.; Stoffers, J.; Kil, A. Factors affecting employee performance: A systematic literature review. J. Adv. Manag. Res. 2019, 16, 329–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamantidis, A.D.; Chatzoglou, P. Factors affecting employee performance: An empirical approach. Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag. 2019, 68, 171–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, J.; Malik, M.I.; Anwar, A. Knowledge Management Influencing Employee Performance in Telecommunication Industry. FWU J. Soc. Sci. 2018, 12, 135–146. [Google Scholar]

- Rudin, J.; Ruane, S.; Ross, L.; Farro, A.; Billing, T. Hostile territory: Employers’ unwillingness to accommodate transgender employees. Equal. Divers. Inclusion: Int. J. 2014, 33, 721–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PTA. 2018. Available online: https://www.pta.gov.pk/annual-reports/annrep0607/chapter_1.pdf (accessed on 30 October 2022).

- Saeed, R.; Lodhi, R.N.; Ahmed, S.; Munir, H.M.; Dustgeer, F.; Sami, A.; Mahmood, Z.; Ahmad, M. Effect of Conflicts in Organizations and its Resolution in Pakistan. World Appl. Sci. J. 2013, 26, 393–398. [Google Scholar]

- Hobfoll, S.E. The influence of culture, community, and the nested self in the stress process: Advancing conservation of resources theory. Appl. Psychol. Int. Rev. 2001, 50, 337–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. Am. Psychol. 1989, 44, 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.; Gray, D.; McHardy, J.; Taylor, K. Employee trust and workplace Performance. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2015, 116, 361–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Selnes, F. Antecedents and consequences of trust and satisfaction in buyer-seller Relationships. Euro. J. Mark. 1998, 32, 305–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalshoven, K.; Boon, C.T. Ethical leadership, employee well-being, and helping: The moderating role of human resource management. J. Pers. Psychol. 2012, 11, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, K.J.; Kacmar, K.M.; Zivnuska, S. An investigation of abusive supervision as a predictor of performance and the meaning of work as a moderator of the relationship. Lead. Quar. 2007, 18, 252–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhry, N. Workplace Bullying and Incivility: More than Meets the Eye. Sci. Pract. 2016, 2, 5–8. [Google Scholar]

- Cortina, L.M.; Magley, V.J. Incivility in the workplace: Incidence and impact. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2001, 6, 64–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, S.E.; Luo, Y.; Schuler, R.S. Managing Human Resources in Cross-Border Alliances; Routledge: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, S.; Chadee, D. Ethical leadership, self-efficacy and job satisfaction in China: The moderating role of guanxi. Pers. Rev. 2017, 46, 371–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porath, C.L.; Pearson, C. The price of incivility. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2013, 91, 115–122. [Google Scholar]

- Hogan, R.; Kaiser, R.B. What we know about Leadership. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2005, 9, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gentry, W.A.; Clark, M.A.; Young, S.F.; Cullen, K.L.; Zimmerman, L. How displaying empathic concern may differentially predict career derailment potential for women and men leaders in Australia. Leadersh. Q. 2015, 26, 641–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furnham, A.; Taylor, J. The Dark Side of Behavior at Work; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bunk, J.A.; Magley, V.J. The role of appraisals and emotions in understanding experiences of workplace incivility. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2013, 18, 87–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smidt, O.; De Beer, L.T.; Brink, L.; Leiter, M.P. The validation of a workplace incivility scale within the South African banking industry. SA J. Ind. Psychol. 2016, 42, 13–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pearson, C.M.; Porath, C.L. On the nature of consequences, and remedies of workplace incivility: No time for “nice”? Think again. Acad. Manag. Exec. 2005, 19, 7–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.; Cortina, L.M. Interpersonal Mistreatment in the Workplace: The Interface and Impact of General Incivility and Sexual Harassment. J. Appl. Psychol. 2005, 90, 483–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mathis, R.L.; Jackson, J.H. Human Resource Management, 10th ed.; South-Western College Pub: Mason, OH, USA, 2009; pp. 75–76. [Google Scholar]

- Penny, L.; Spector, P. Job stress, incivility, and counterproductive work behavior (CWB): The moderating role of negative affectivity. J. Organ. Behav. 2005, 26, 777–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidle, S.D. Workplace incivility: How should employees and managers respond? Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2009, 23, 88–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reio, T.G., Jr.; Ghosh, R. Antecedents and outcomes of workplace incivility: Implications for human resources development research and practice. Hum. Resour. Dev. Q. 2009, 20, 237–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sliter, M.; Jex, S.; Wolford, K.; McInnerney, J. How rude! Emotional labor as a mediator between customer incivility and employee outcomes. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2010, 15, 468–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.; Lee, A. Work and non-work outcomes of workplace incivility: Does family support help? J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2011, 16, 95–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hussain, S.; Shujahat, M.; Malik, M.I.; Iqbal, S.; Mir, F.N. Contradictory results on the mediating roles of two dimensions of trust between transformational leadership and employee outcomes. J. Organ. Eff. People Perform. 2018, 5, 39–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poon, J.M.L. Trust-in-supervisor and helping coworkers: Moderating effect of perceived politics. J. Manag. Psychol. 2006, 21, 518–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharkie, R. Trust in leadership is vital for employee performance. Manag. Res. News 2009, 32, 491–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, M.A.; Neal, A.; Parker, S.K. A New Model of Work Role Performance: Positive Behavior in Uncertain and Interdependent Contexts. Acad. Manag. J. 2007, 50, 327–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mcallister, D.J. Affect and Cognitive Based Trust As foundations for Interpersonal Cooperation In Organizations. Acad. Manag. J. 1995, 38, 24–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Sarstedt, M.; Hopkins, L.; Kuppelwieser, V.G. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM): An emerging tool in business research. Eur. Rev. 2014, 26, 106–121. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, K.K.K. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) techniques using SmartPLS. Mark. Bull. 2013, 24, 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Garson, G.D. Partial Least Squares: Regression and Structural Equation Models; Statistical Associates Publishers: Asheboro, NC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Mooi, E.A. Response-based segmentation using finite mixture partial least squares. In Data Mining; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2010; pp. 19–49. [Google Scholar]

- Svensson, G.; Ferro, C.; Høgevold, N.; Padin, C.; Varela, J.C.S.; Sarstedt, M. Framing the triple bottom line approach: Direct and mediation effects between economic, social and environmental elements. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 197, 972–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsey, J.B. Tests for specification errors in classical linear least-squares regression analysis. J. Roya. Stat. Soc. Ser. B 1969, 31, 350–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, J.; Wang, G.; Liu, H.; Song, D.; He, C. Linking authoritarian leadership to employee creativity: The influences of leader–member exchange, team identification and power distance. Chin. Manag. Stud. 2018, 12, 384–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.; Cortina, L.M.; Magley, V.J. Personal and workgroup incivility: Impact on work and health outcomes. J. Appl. Psychol. 2008, 93, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Ferris, D.L.; Kwan, H.K.; Yan, M.; Zhou, M.; Hong, Y. Self-Love’s Lost Labor: A Self-Enhancement Model of Workplace Incivility. Acad. Manag. J. 2013, 56, 1199–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beattie, L.; Griffin, B. Day-level fluctuations in stress and engagement in response to workplace incivility: A diary study. Work Stress 2014, 28, 124–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifirad, M.S. Can incivility impair team’s creative performance through paralyzing employee’s knowledge sharing? A multi-level approach. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2016, 37, 200–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahim, A.; Cosby, D.M. A model of workplace incivility, job burnout, turnover intentions, and job performance. J. Manag. Dev. 2016, 35, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afsar, B.; Saeed, B.B. Subordinate’s trust in the supervisor and its impact on organizational effectiveness. Port. J. Manag. Stud. 2011, 16, 13–28. [Google Scholar]

- Rayner, C. The incidence of workplace bullying. J. Community Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1997, 7, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, M.K.; Ganster, D.C.; Pagon, M. Social undermining in the workplace. Acad. Manag. J. 2002, 45, 331–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuman, J.H.; Baron, R.A. Workplace violence and workplace aggression: Evidence concerning specific forms, potential causes, and preferred targets. J. Manag. 1998, 24, 391–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spector, P.E.; Jex, S.M. Development of four self-report measures of job stressors and strain: Interpersonal conflict at work scale, organizational constraints scale, quantitative workload inventory, and physical symptoms inventory. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 1998, 3, 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortina, L.M.; Magley, V.J. Patterns and profiles of response to incivility in the Workplace. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2009, 14, 272–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Porath, C.L.; Erez, A. Does rudeness really matter? The effects of rudeness on task performance and helpfulness. Acad. Manag. J. 2007, 50, 1181–1197. [Google Scholar]

- Porath, C.L.; Erez, A. Overlooked but not untouched: How rudeness reduces onlookers’ performance on routine and creative tasks. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2009, 109, 29–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C.; Jackson, S.E. Maslach Burnout Inventory Manual, 2nd ed.; Consulting Psychologists Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | Category | No. of Respondents | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 26–35 years | 43 | 17.1 |

| 36–45 years | 138 | 54.8 | |

| 46–55 years | 71.0 | 28.2 | |

| Total | 252 | 100 | |

| Experience | 1–5 years | 97 | 38.5 |

| 6–10 years | 149 | 59.1 | |

| Over 11 years | 06 | 02.4 | |

| Total | 252 | 100 | |

| Gender | Male | 252 | 100 |

| Female | 00 | 00.0 | |

| Total | 252 | 100 | |

| Education | Bachelor’s | 39 | 15.1 |

| Master’s | 44 | 17.5 | |

| MS | 170 | 67.5 | |

| Total | 252 | 100 |

| Variable | No. of Items | Composite Reliability | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Workplace incivility | 14 | 0.944 | 0.749 |

| Employee performance | 10 | 0.968 | 0.728 |

| Trust in supervisor | 11 | 0.968 | 0.736 |

| Item | EP | TS | WI |

|---|---|---|---|

| EP1 | 0.834 | ||

| EP2 | 0.843 | ||

| EP4 | 0.845 | ||

| EP5 | 0.853 | ||

| EP6 | 0.865 | ||

| EP7 | 0.803 | ||

| EP8 | 0.869 | ||

| EP9 | 0.902 | ||

| EP10 | 0.864 | ||

| TS1 | 0.862 | ||

| TS2 | 0.837 | ||

| TS3 | 0.885 | ||

| TS4 | 0.856 | ||

| TS5 | 0.861 | ||

| TS6 | 0.852 | ||

| TS7 | 0.851 | ||

| TS8 | 0.884 | ||

| TS9 | 0.844 | ||

| TS10 | 0.857 | ||

| TS11 | 0.847 | ||

| WI1 | 0.852 | ||

| WI2 | 0.870 | ||

| WI3 | 0.871 | ||

| WI4 | 0.879 | ||

| WI5 | 0.875 | ||

| WI6 | 0.844 | ||

| WI8 | 0.876 | ||

| WI9 | 0.867 | ||

| WI10 | 0.866 | ||

| WI11 | 0.864 | ||

| WI12 | 0.862 | ||

| WI13 | 0.867 | ||

| WI14 | 0.861 |

| WI | E-Performance | TS | |

|---|---|---|---|

| WI | 0.865 | ||

| E-Performance | 0.595 | 0.853 | |

| TS | 0.612 | 0.639 | 0.857 |

| Original Sample (O) | Sample Mean (M) | Standard Deviation (STDEV) | T-Statistics | p-Values | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TS -> EP | 0.708 | 0.702 | 0.07 | 10.107 | 0.000 |

| WI -> EP | −0.278 | −0.283 | 0.071 | 3.918 | 0.000 |

| WI -> TS | −0.922 | −0.921 | 0.026 | 35.167 | 0.000 |

| WI -> TS -> EP | −0.653 | −0.645 | 0.059 | 11.120 | 0.000 |

| Original Sample (O) | Sample Mean (M) | Standard Deviation (STDEV) | T-Statistics (|O/STDEV|) | p Values | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CI -> EP | −0.077 | −0.082 | 0.065 | 1.181 | 0.238 |

| CI -> TS | −0.569 | −0.568 | 0.068 | 8.42 | 0.000 |

| SI -> EP | −0.202 | −0.207 | 0.052 | 3.879 | 0.000 |

| SI -> TS | −0.368 | −0.368 | 0.066 | 5.579 | 0.000 |

| TS -> EP | 0.712 | 0.701 | 0.070 | 10.138 | 0.000 |

| Nonlinear Relationship | Coefficient | p-Value | f2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| SI*SI ---> TS | −0.021 | 0.467 | 0.001 |

| CI*CI ---> TS | −0.050 | 0.238 | 0.005 |

| SI*SI ---> EP | −0.027 | 0.391 | 0.002 |

| TS*TS ---> EP | 0.012 | 0.779 | 0.000 |

| CI*CI ---> EP | −0.060 | 0.130 | 0.006 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Saleem, F.; Malik, M.I.; Asif, I.; Qasim, A. Workplace Incivility and Employee Performance: Does Trust in Supervisors Matter? (A Dual Theory Perspective). Behav. Sci. 2022, 12, 513. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12120513

Saleem F, Malik MI, Asif I, Qasim A. Workplace Incivility and Employee Performance: Does Trust in Supervisors Matter? (A Dual Theory Perspective). Behavioral Sciences. 2022; 12(12):513. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12120513

Chicago/Turabian StyleSaleem, Farida, Muhammad Imran Malik, Iqra Asif, and Awais Qasim. 2022. "Workplace Incivility and Employee Performance: Does Trust in Supervisors Matter? (A Dual Theory Perspective)" Behavioral Sciences 12, no. 12: 513. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12120513

APA StyleSaleem, F., Malik, M. I., Asif, I., & Qasim, A. (2022). Workplace Incivility and Employee Performance: Does Trust in Supervisors Matter? (A Dual Theory Perspective). Behavioral Sciences, 12(12), 513. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12120513