Study of the Unidimensionality of the Subjective Measurement Scale of Schizophrenia Coping Oral Health Profile and Index: SCOOHPI

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

2.1. SCOOHPI Scale Items

2.2. Studied Population and Data Collection

2.3. Dental Investigations

2.4. Dealing with Missing Data

2.5. Psychometric Validation

2.5.1. Validity of the Scale (the First Two Steps)

2.5.2. Scale Reliability

2.5.3. Validity of the Scale

2.6. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Missing Data

3.2. Internal Consistency

3.3. Content Validity

3.4. Face Validity

3.5. Construct Validity

3.6. Structure Validity

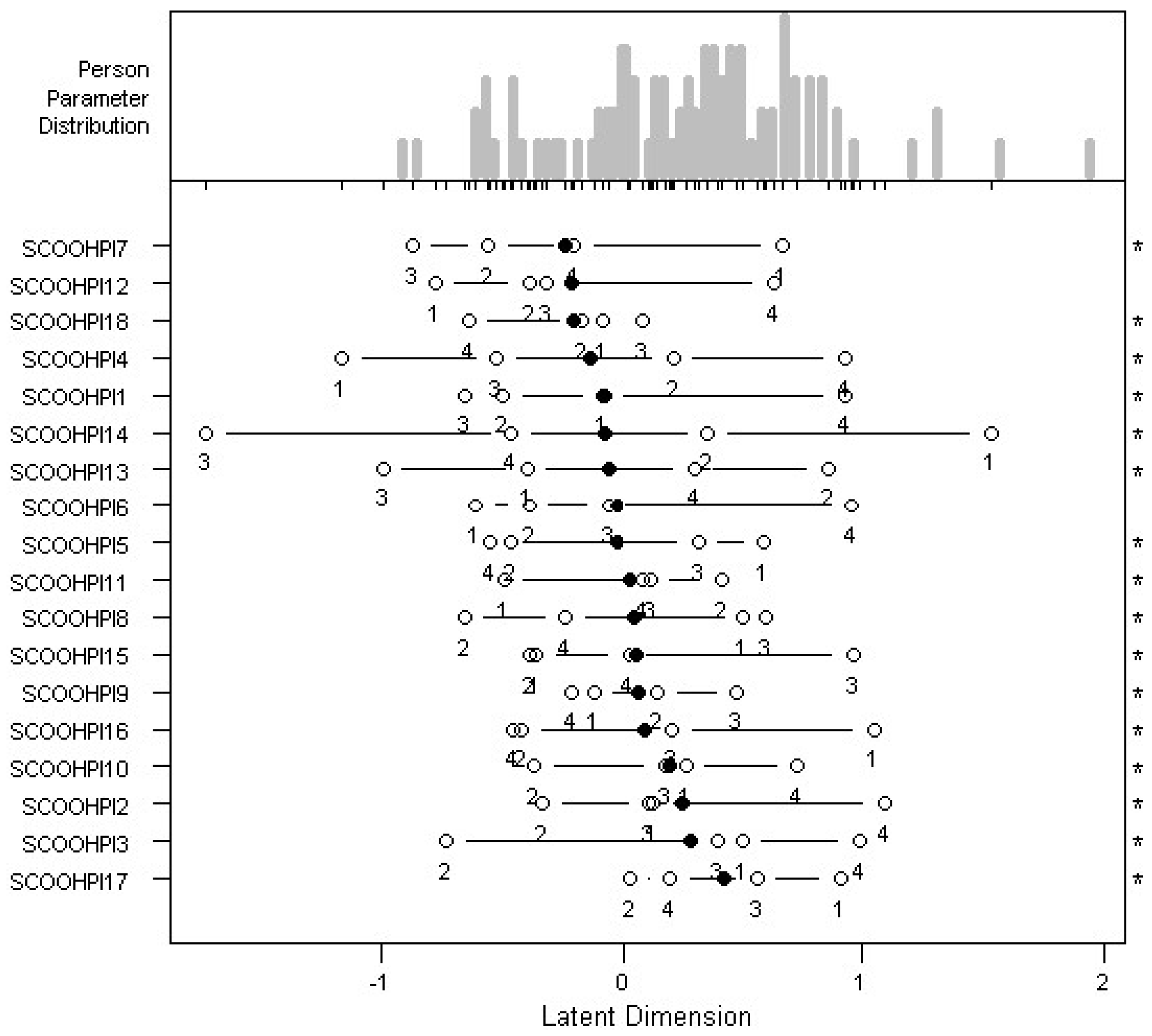

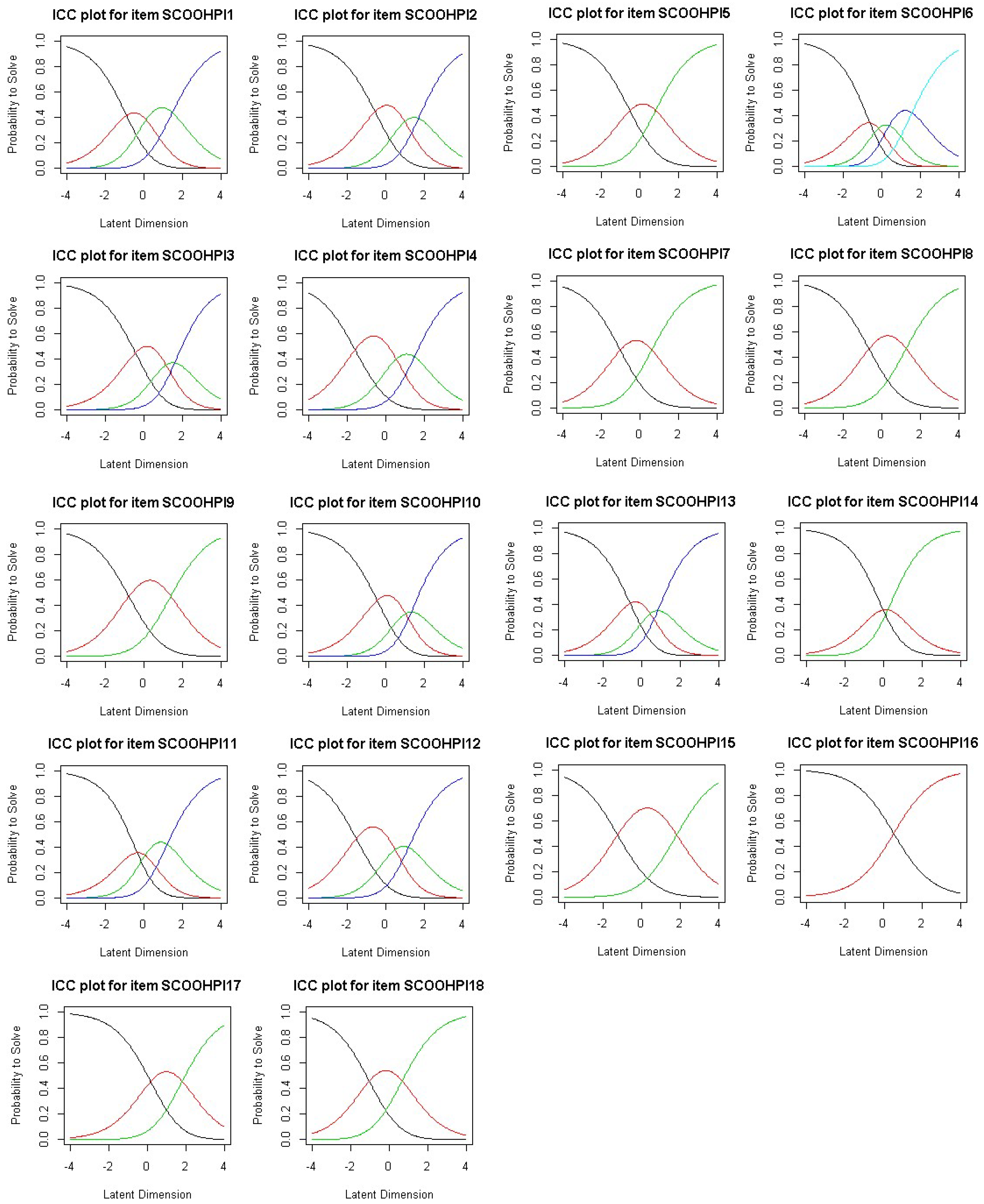

3.6.1. Partial Credit Model

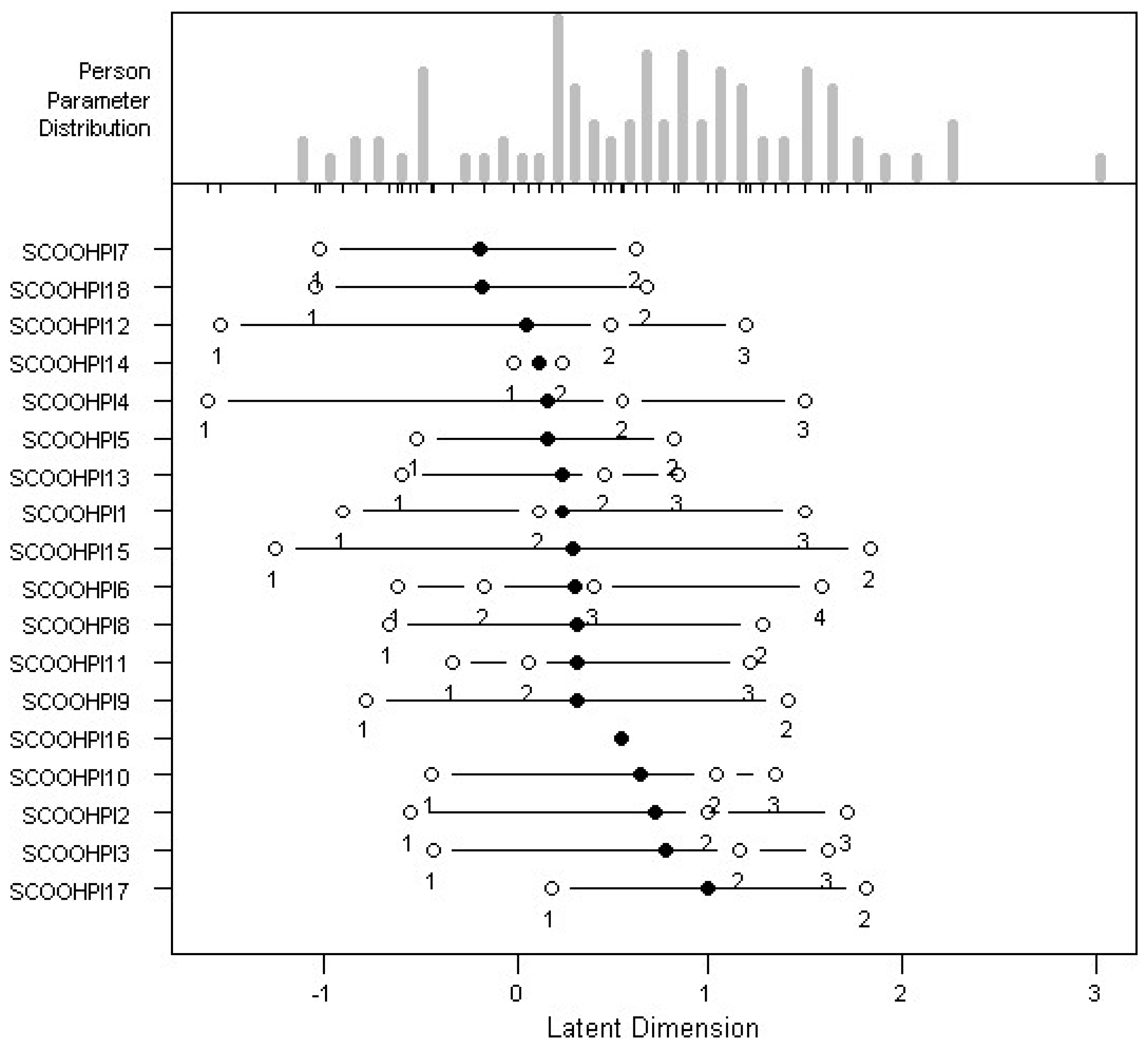

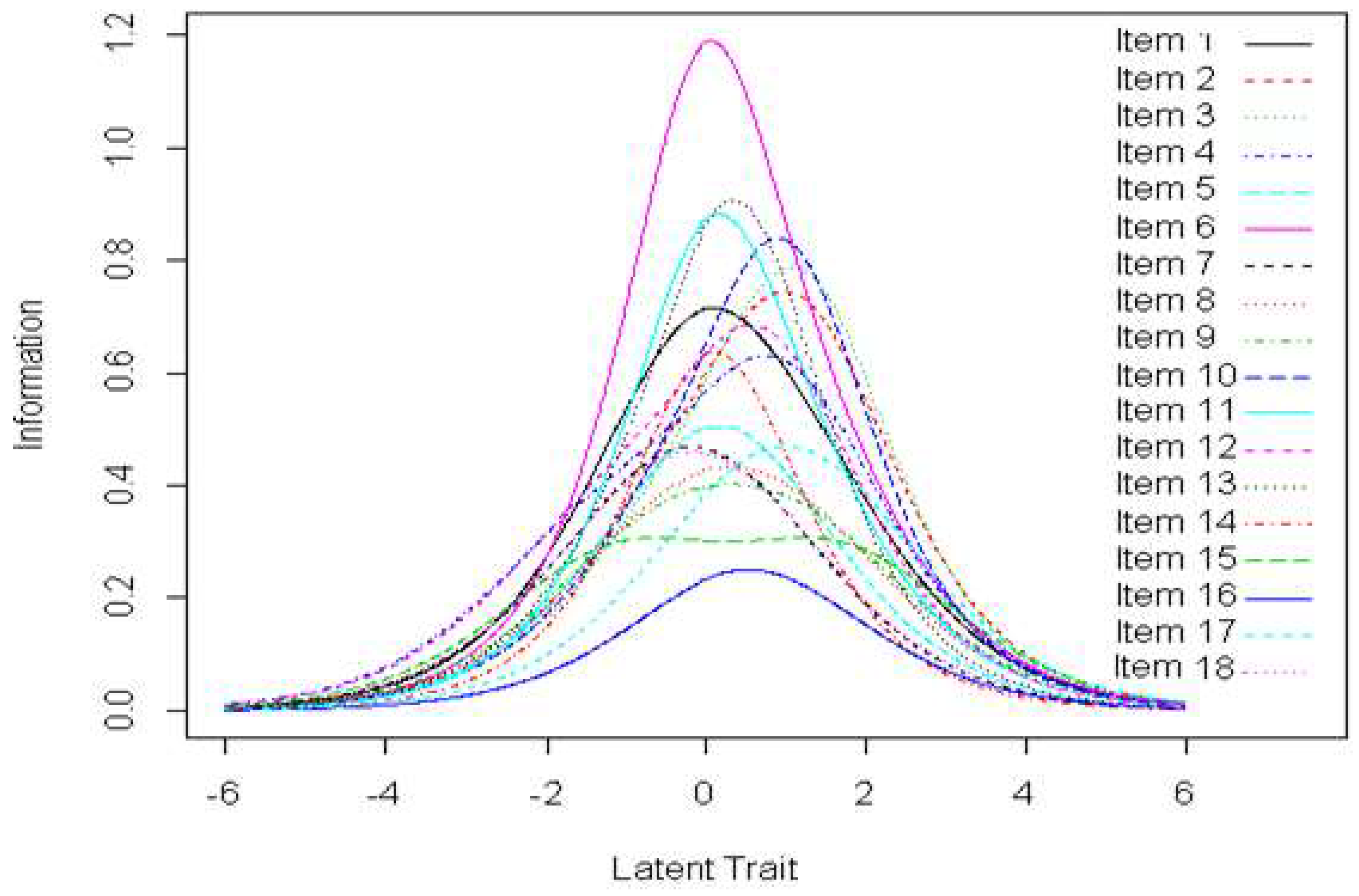

3.6.2. Partial Credit Model with Data Smoothing

3.7. Relationship between SCOOHPI and Sociodemographic and Clinical Variables

4. Discussion

4.1. Internal Consistency

4.2. Construct Validity

4.3. Structure Validity

4.4. Data Smoothing for the Partial Credit Model

4.5. Limitations

4.6. SCOOHPI Scale

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. The Initial SCOOHPI Scale

| Actuellement et/ou au cours des 15 derniers jours, en relation avec ma santé buccodentaire, j’ai pu me dire: | Jamais (0) | Rarement (1) | Parfois (2) | Souvent (3) | Toujours (4) |

| Je me crée des plaisirs simples (promenade, boire un café, écouter de la musique, regarder la télé…) I am looking for simple pleasures (walk, drink coffee, listen to music, watch TV …) |  |  |  |  |  |

| Je sors de chez moi I go out of my home |  |  |  |  |  |

| Je pratique une activité de loisirs (musique, chant, dessin, cinéma, promenade…) I have a hobby (music, singing, drawing, movie, and ballads …) |  |  |  |  |  |

| Quand je suis dans l’action, je me sens bien When I move, I feel good |  |  |  |  |  |

| Je me sens tenu(e) en otage par le sucre I feel trapped by my relationship with sugar |  |  |  |  |  |

| Je mange équilibré I have a balanced diet |  |  |  |  |  |

| Je pense à me laver (douche, bain, toilette) I think about washing myself (shower, bath, cleaning) |  |  |  |  |  |

| Je me brosse les dents et/ou mon appareil dentaire I brush my teeth and/or my denture |  |  |  |  |  |

| Je néglige mon hygiène buccodentaire I neglect my oral health |  |  |  |  |  |

| Je prends soin de ma bouche pour avoir une bonne haleine I take care of my mouth to have a good breath |  |  |  |  |  |

| Je prends soin de ma bouche pour avoir une bonne dentition I take care of my mouth to have a good dentition |  |  |  |  |  |

| Je mange sainement I eat healthy food |  |  |  |  |  |

| Je pense à boire de l’eau (plate ou pétillante) quand j’ai la bouche sèche I think about drinking water (normal or sparkling) when my mouth is dry |  |  |  |  |  |

| J’arrive à coordonner le mouvement de mes mains pour me brosser les dents I can coordinate the movement of my hands in order to brush my teeth |  |  |  |  |  |

| J’oublie de me brosser les dents I forget to brush my teeth |  |  |  |  |  |

| L’alcool, le tabac, les drogues ont des effets négatifs sur la santé buccodentaire Alcohol, tobacco, drugs have negative effects on the oral health |  |  |  |  |  |

| Je m’organise pour aller chez le dentiste I manage to visit my dentist |  |  |  |  |  |

| J’ai peur d’aller chez le dentiste I’m afraid to go to the dentist |  |  |  |  |  |

Appendix B. The SCOOHPI Scale after Grouping the Response Modalities

| Actuellement et/ou au cours des 15 derniers jours, en relation avec ma santé buccodentaire, j’ai pu me dire: | Jamais (0) | Rarement (1) | Parfois (2) | Souvent (3) |

| Je mange équilibré I have a balanced diet |  |  |  |  |

| Actuellement et/ou au cours des 15 derniers jours, en relation avec ma santé buccodentaire, j’ai pu me dire: | Jamais (0) | Rarement et Parfois (1) | Souvent (2) | Toujours (3) |

| Je me crée des plaisirs simples (promenade, boire un café, écouter de la musique, regarder la télé…) I am looking for simple pleasures (walk, drink coffee, listen to music, watch TV …) |  |  |  |  |

| Je sors de chez moi I go out of my home |  |  |  |  |

| Je pratique une activité de loisirs (musique, chant, dessin, cinéma, promenade…) I have a hobby (music, singing, drawing, movie, and ballads …) |  |  |  |  |

| Quand je suis dans l’action, je me sens bien When I move, I feel good |  |  |  |  |

| Je prends soin de ma bouche pour avoir une bonne haleine I take care of my mouth to have a good breath |  |  |  |  |

| Je mange sainement I eat healthy food |  |  |  |  |

| Je pense à boire de l’eau (plate ou pétillante) quand j’ai la bouche sèche I think about drinking water (normal or sparkling) when my mouth is dry |  |  |  |  |

| Actuellement et/ou au cours des 15 derniers jours, en relation avec ma santé buccodentaire, j’ai pu me dire: | Jamais (0) | Rarement (1) | Parfois et Souvent (2) | Toujours (3) |

| Je prends soin de ma bouche pour avoir une bonne dentition I take care of my mouth to have a good dentition |  |  |  |  |

| Actuellement et/ou au cours des 15 derniers jours, en relation avec ma santé buccodentaire, j’ai pu me dire: | Jamais (0) | Rarement, Parfois et Souvent (1) | Toujours (2) |

| Je me sens tenu(e) en otage par le sucre I feel trapped by my relationship with sugar |  |  |  |

| Je pense à me laver (douche, bain, toilette) I think about washing myself (shower, bath, cleaning) |  |  |  |

| Je me brosse les dents et/ou mon appareil dentaire I brush my teeth and/or my denture |  |  |  |

| Je néglige mon hygiène buccodentaire I neglect my oral health |  |  |  |

| J’arrive à coordonner le mouvement de mes mains pour me brosser les dents I can coordinate the movement of my hands in order to brush my teeth |  |  |  |

| J’oublie de me brosser les dents I forget to brush my teeth |  |  |  |

| Je m’organise pour aller chez le dentiste I manage to visit my dentist |  |  |  |

| J’ai peur d’aller chez le dentiste I’m afraid to go to the dentist |  |  |  |

| Actuellement et/ou au cours des 15 derniers jours, en relation avec ma santé buccodentaire, j’ai pu me dire: | Jamais, Rarement et Parfois (0) | Souvent et Toujours (1) |

| L’alcool, le tabac, les drogues ont des effets négatifs sur la santé buccodentaire Alcohol, tobacco, drugs have negative effects on the oral health |  |  |

References

- Jablensky, A. Epidemiology of schizophrenia: The global burden of disease and disability. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2000, 250, 274–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurtz, M.M.; Wexler, B.E.; Fujimoto, M.; Shagan, D.S.; Seltzer, J.C. Symptoms versus neurocognition as predictors of change in life skills in schizophrenia after outpatient rehabilitation. Schizophr. Res. 2008, 102, 303–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, S.; Inskip, H.; Barraclough, B. Causes of the excess mortality of schizophrenia. Br. J. Psychiatry J. Ment. Sci. 2000, 177, 212–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Persson, K.; Olin, E.; Ostman, M. Oral health problems and supportas experienced by people with severe mental illness living in community-based subsidised housing a qualitative study. Health Soc. Care Community 2010, 18, 529–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilbourne, A.M.; Horvitz-Lennon, M.; Post, E.P.; McCarthy, J.F.; Cruz, M.; Welsh, D.; Blow, F.C. Oral health in Veterans Affairs patients diagnosed withserious mental illness. J. Public Health Dent. 2007, 67, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denis, F.; Goueslard, K.; Siu-Paredes, F.; Amador, G.; Rusch, E.; Bertaud, V.; Quantin, C. Oral health treatment habits of people with schizophrenia in France: A retrospective cohort study. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0229946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folkman, S.; Moskowitz, J.T. Coping: Pitfalls and promise. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2004, 55, 745–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siu-Paredes, F.; Rude, N.; Rouached, I.; Rat, C.; Mahalli, R.; El-Hage, W.; Rozas, K.; Denis, F. Dimensional Structure and Preliminary Results of the External Constructs of the Schizophrenia Coping Oral Health Profile and Index (SCOOHPI). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Arán, A.; Vieta, E.; Reinares, M.; Colom, F.; Torrent, C.; Sanchez-Moreno, J.; Benabarre, A.; Goikolea, J.M.; Comes, M.; Salamero, M. Cognitive function across manic or hypomanic, depressed, and euthymic states in bipolar disorder. Am. J. Psychiatry 2004, 161, 262–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, K.-Y.; Yang, N.-P.; Chou, P.; Chiu, H.-J.; Chi, L.-Y. Comparison of oral health between inpatients with schizophrenia and disabled people or the general population. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 2012, 111, 214–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paredes, F.S.; Rude, N.; Moussa-Badran, S.; Pelletier, J.F.; Rat, C.; Denis, F. Coping strategies for oral health problems by people with schizophrenia. Transl. Neurosci. 2019, 10, 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denis, F.; Siu-Paredes, F.; Maitre, Y.; Amador, G.; Rude, N. A qualitative study on experiences of persons with schizophrenia in oral-health-related quality of life. Braz. Oral Res. 2021, 35, e050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carver, C.S.; Connor-Smith, J. Personality and Coping. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2010, 61, 679–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hofer, A.; Mizuno, Y.; Frajo-Apor, B.; Kemmler, G.; Suzuki, T.; Pardeller, S.; Welte, A.S.; Sondermann, C.; Mimura, M.; Wartelsteiner, F.; et al. Resilience, internalized stigma, self-esteem, and hopelessness among people with schizophrenia: Cultural comparison in Austria and Japan. Schizophr. Res. 2016, 171, 86–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kato, T. Development of the Coping Flexibility Scale: Evidence for the coping flexibility hypothesis. J. Couns. Psychol. 2012, 59, 262–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, B.C. Validation of a Caregiver Strain Index. J. Gerontol. 1983, 38, 344–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, K.E.; Moore, S.H. Attitudes toward self-care: A consumer study. Med. Care 1980, 18, 872–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, J.T.; Bobula, J.A.; Short, T.B.; Mischel, M. A Functional Dementia Scale. J. Fam. Pract. 1983, 16, 499–503. [Google Scholar]

- Dawson, C.; Schirmer, M.; Beck, L. A patient self-disclosure instrument. Res. Nurs. Health 1984, 7, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdi, H.; Williams, L.J. Principal component analysis. WIREs Comput. Stat. 2010, 2, 433–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasch, G. Studies in Mathematical Psychology: I. Probabilistic Models for Some Intelligence and Attainment Tests; Nielsen & Lydiche: Copenhagen, Denmark, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Andrich, D. A rating formulation for ordered response categories. Psychometrika 1978, 43, 561–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masters, G.N. A rasch model for partial credit scoring. Psychometrika 1982, 47, 149–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, E.V. Detecting and evaluating the impact of multidimensionality using item fit statistics and principal component analysis of residuals. J. Appl. Meas. 2002, 3, 205–231. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kaiser, H.F. The varimax criterion for analytic rotation in factor analysis. Psychometrika 1958, 23, 187–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masters, G.N.; Wright, B.D. The Partial Credit Model. In Handbook of Modern Item Response Theory; van der Linden, W.J., Hambleton, R.K., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1997; pp. 101–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, J.G.; Vermilion, J.R. 1960. Available online: http://www.mah.se (accessed on 25 March 2016).

- World Health Organization. Oral Health Surveys: Basic Methods; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Glasson-Cicognani, M.; Berchtold, A. Imputation des données manquantes: Comparaison de différentes approches. In 42èmes Journées de Statistique; The Institut National d’Etudes Démographiques: Paris, France, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Lynn, M.R. Determination and quantification of content validity. Nurs. Res. 1986, 35, 382–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, L.L. Instrument review: Getting the most from a panel of experts. Appl. Nurs. Res. 1992, 5, 194–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, J.S.; Davis, L.L. Selection and use of content experts for instrument development. Res. Nurs. Health 1997, 20, 269–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polit, D.F.; Beck, C.T. Nursing Research: Principles and Methods; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Nevo, B. Face Validity Revisited. J. Educ. Meas. 1985, 22, 287–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronbach, L.J. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika 1951, 16, 297–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesbah, M. From Measurement to Analysis. In Rasch Models in Health; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012; pp. 235–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, D.T.; Fiske, D.W. Convergent and discriminant validation by the multitrait-multimethod matrix. Psychol. Bull. 1959, 56, 81–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokkink, L.B.; Terwee, C.B.; Patrick, D.L.; Alonso, J.; Stratford, P.W.; Knol, D.L.; Bouter, L.M.; de Vet, H.C. The COSMIN study reached international consensus on taxonomy, terminology, and definitions of measurement properties for health-related patient-reported outcomes. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2010, 63, 737–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bond, T.G.; Fox, C.M. Applying the Rasch Model: Fundamental Measurement in the Human Sciences; Psychology Press: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linacre, J.M. A User’s Guide to WINSTEPS® Rasch-Model Computer Programs: Program Manual 4.4. 6; Mesa-Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally, J.C. An overview of psychological measurement. In Clinical Diagnosis of Mental Disorders: A Handbook; Wolman, B.B., Ed.; Springer US: New York City, NY, USA, 1978; pp. 97–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siu-Paredes, F.; Rude, N.; Rat, C.; Reynaud, M.; Hamad, M.; Moussa-Badran, S.; Denis, F. The Schizophrenia Coping Oral Health Profile. Development and Feasibility. Transl. Neurosci. 2018, 9, 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denis, F.; Hamad, M.; Trojak, B.; Tubert-Jeannin, S.; Rat, C.; Pelletier, J.F.; Rude, N. Psychometric characteristics of the “General Oral Health Assessment Index (GOHAI)” in a French representative sample of patients with schizophrenia. BMC Oral Health 2017, 17, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colaço, J.; Muniz, F.W.M.G.; Peron, D.; Marostega, M.G.; Dias, J.J.; Rösing, C.K.; Colussi, P.R.G. Qualidade de vida relacionada à saúde bucal e fatores associados em idosos: Um estudo transversal com amostra representativa. Ciência Saúde Coletiva 2020, 25, 3901–3912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Linden, W.J. The changing conception of measurement in education and psychology. Appl. Psychol. Meas. 1986, 10, 325–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denis, F.; Bizien, P.; Tubert-Jeannin, S.; Hamad, M.; Trojak, B.; Rude, N.; Hardouin, J.B. A Rasch Analysis between Schizophrenic Patients and the General Population. Transl. Neurosci. 2017, 8, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, S.S.; Mathiasen, K.; Christensen, K.B.; Makransky, G. Psychometric analysis of the Patient Health Questionnaire in Danish patients with an implantable cardioverter defibrillator (The DEFIB-WOMEN study). J. Psychosom. Res. 2016, 90, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franchignoni, M.; Giordano, A.; Levrini, L.; Ferriero, G.; Franchignoni, F. Rasch analysis of the Geriatric Oral Health Assessment Index. Eur. J. Oral Sci. 2010, 118, 278–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Location | Threshold 1 | Threshold 2 | Threshold 3 | Threshold 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SCOOHPI1 | −0.07708 | −0.08235 | −0.49956 | −0.65266 | 0.92626 |

| SCOOHPI2 | 0.25188 | 0.13451 | −0.33656 | 0.11796 | 1.09162 |

| SCOOHPI3 | 0.28787 | 0.50080 | −0.73109 | 0.39781 | 0.98394 |

| SCOOHPI4 | −0.13658 | −1.16237 | 0.21367 | −0.52500 | 0.92738 |

| SCOOHPI5 | −0.02838 | 0.59144 | −0.46858 | 0.32007 | −0.55644 |

| SCOOHPI6 | −0.02839 | −0.61307 | −0.38894 | −0.06102 | 0.94945 |

| SCOOHPI7 | −0.24321 | 0.66568 | −0.55963 | −0.87389 | −0.20501 |

| SCOOHPI8 | 0.05277 | 0.50725 | −0.65809 | 0.59843 | −0.23652 |

| SCOOHPI9 | 0.07202 | −0.12227 | 0.14941 | 0.47958 | −0.21863 |

| SCOOHPI10 | 0.20209 | 0.26677 | −0.37045 | 0.18009 | 0.73195 |

| SCOOHPI11 | 0.03242 | −0.49277 | 0.41420 | 0.12084 | 0.08742 |

| SCOOHPI12 | −0.21408 | −0.78106 | −0.38933 | −0.31842 | 0.63248 |

| SCOOHPI13 | −0.05909 | −0.39943 | 0.85682 | −0.99667 | 0.30292 |

| SCOOHPI14 | −0.07470 | 1.53286 | 0.35857 | −1.72648 | −0.46374 |

| SCOOHPI15 | 0.06027 | −0.35904 | −0.38641 | 0.96121 | 0.02530 |

| SCOOHPI16 | 0.09597 | 1.04624 | −0.42061 | 0.21328 | −0.45503 |

| SCOOHPI17 | 0.42642 | 0.90643 | 0.03499 | 0.56258 | 0.20169 |

| SCOOHPI18 | −0.20367 | −0.08559 | −0.17496 | 0.08713 | −0.64125 |

| Location | Threshold 1 | Threshold 2 | Threshold 3 | Threshold 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SCOOHPI1 | 0.23764 | −0.89722 | 0.11623 | 1.49391 | NA |

| SCOOHPI2 | 0.71969 | −0.55180 | 0.99642 | 1.71444 | NA |

| SCOOHPI3 | 0.78045 | −0.43402 | 1.15878 | 1.61657 | NA |

| SCOOHPI4 | 0.15413 | −1.59353 | 0.55462 | 1.50130 | NA |

| SCOOHPI5 | 0.15621 | −0.51304 | 0.82545 | NA | NA |

| SCOOHPI6 | 0.30009 | −0.61055 | −0.16463 | 0.39194 | 1.58362 |

| SCOOHPI7 | −0.19463 | −1.01576 | 0.62649 | NA | NA |

| SCOOHPI8 | 0.30706 | −0.66078 | 1.27490 | NA | NA |

| SCOOHPI9 | 0.31380 | −0.77984 | 1.40745 | NA | NA |

| SCOOHPI10 | 0.64687 | −0.44213 | 1.03951 | 1.34322 | NA |

| SCOOHPI11 | 0.31273 | −0.33621 | 0.05742 | 1.21697 | NA |

| SCOOHPI12 | 0.05061 | −1.52920 | 0.48662 | 1.19442 | NA |

| SCOOHPI13 | 0.23520 | −0.59128 | 0.45031 | 0.84658 | NA |

| SCOOHPI14 | 0.10930 | −0.01401 | 0.23261 | NA | NA |

| SCOOHPI15 | 0.29194 | −1.24631 | 1.83019 | NA | NA |

| SCOOHPI16 | 0.53556 | 0.53556 | NA | NA | NA |

| SCOOHPI17 | 0.99623 | 0.17489 | 1.81756 | NA | NA |

| SCOOHPI18 | −0.17863 | −1.03576 | 0.67851 | NA | NA |

| Outfit MSQ | Infit MSQ | |

|---|---|---|

| SCOOHPI1 | 1.165 | 1.097 |

| SCOOHPI2 | 1.009 | 1.033 |

| SCOOHPI3 | 1.267 | 1.269 |

| SCOOHPI4 | 0.880 | 0.895 |

| SCOOHPI5 | 1.163 | 1.116 |

| SCOOHPI6 | 1.060 | 1.117 |

| SCOOHPI7 | 0.598 | 0.606 |

| SCOOHPI8 | 0.681 | 0.676 |

| SCOOHPI9 | 0.921 | 0.916 |

| SCOOHPI10 | 0.807 | 0.827 |

| SCOOHPI11 | 0.828 | 0.832 |

| SCOOHPI12 | 0.876 | 0.895 |

| SCOOHPI13 | 0.890 | 0.866 |

| SCOOHPI14 | 0.778 | 0.786 |

| SCOOHPI15 | 0.904 | 0.908 |

| SCOOHPI16 | 1.337 | 1.229 |

| SCOOHPI17 | 1.234 | 1.197 |

| SCOOHPI18 | 1.064 | 1.057 |

| Variable | SCOOHPI Scale Overall Score | Wilcoxon Test | Correlation with SCOOHPI | |

| Weight | <81 KG | Mean = 26.22 Standard deviation = 7.24 | 0.51 | −0.14 |

| ≥81 KG | Mean = 24.84 Standard deviation = 8.86 | |||

| Height | <177 Cm | Mean = 26.39 Standard deviation = 7.90 | 0.28 | −0.05 |

| ≥177 Cm | Mean = 24.28 Standard deviation = 7.77 | |||

| Smoking | Yes | Mean = 25.65 Standard deviation = 8.31 | 0.91 | −0.01 |

| No | Mean = 25.74 Standard deviation = 7.32 | |||

| Gender | Male | Mean = 25.33 Standard deviation = 7.71 | 0.50 | 0.07 |

| Female | Mean = 26.59 Standard deviation = 8.38 | |||

| DMFT | <15 | Mean = 25.28 Standard deviation = 7.81 | 0.66 | −0.03 |

| ≥15 | Mean = 26.36 Standard deviation = 8.06 | |||

| OHIS | <1.5 | Mean = 23.82 Standard deviation = 8.61 | 0.07 | 0.12 |

| ≥1.5 | Mean = 27.40 Standard deviation = 6.79 | |||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hamad, M.; Rude, N.; Mesbah, M.; Siu-Paredes, F.; Denis, F. Study of the Unidimensionality of the Subjective Measurement Scale of Schizophrenia Coping Oral Health Profile and Index: SCOOHPI. Behav. Sci. 2022, 12, 442. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12110442

Hamad M, Rude N, Mesbah M, Siu-Paredes F, Denis F. Study of the Unidimensionality of the Subjective Measurement Scale of Schizophrenia Coping Oral Health Profile and Index: SCOOHPI. Behavioral Sciences. 2022; 12(11):442. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12110442

Chicago/Turabian StyleHamad, Mohamad, Nathalie Rude, Mounir Mesbah, Francesca Siu-Paredes, and Frederic Denis. 2022. "Study of the Unidimensionality of the Subjective Measurement Scale of Schizophrenia Coping Oral Health Profile and Index: SCOOHPI" Behavioral Sciences 12, no. 11: 442. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12110442

APA StyleHamad, M., Rude, N., Mesbah, M., Siu-Paredes, F., & Denis, F. (2022). Study of the Unidimensionality of the Subjective Measurement Scale of Schizophrenia Coping Oral Health Profile and Index: SCOOHPI. Behavioral Sciences, 12(11), 442. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12110442