How Does the Concept of Guanxi-circle Contribute to Community Building in Alternative Food Networks? Six Case Studies from China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theory

2.1. Community Building Behavior

2.2. Cognitive Trust and Emotional Trust

2.3. Guanxi and Guanxi-circle

3. Research Methods

3.1. Case Design

3.2. Data Collection

3.3. Analytical Approach

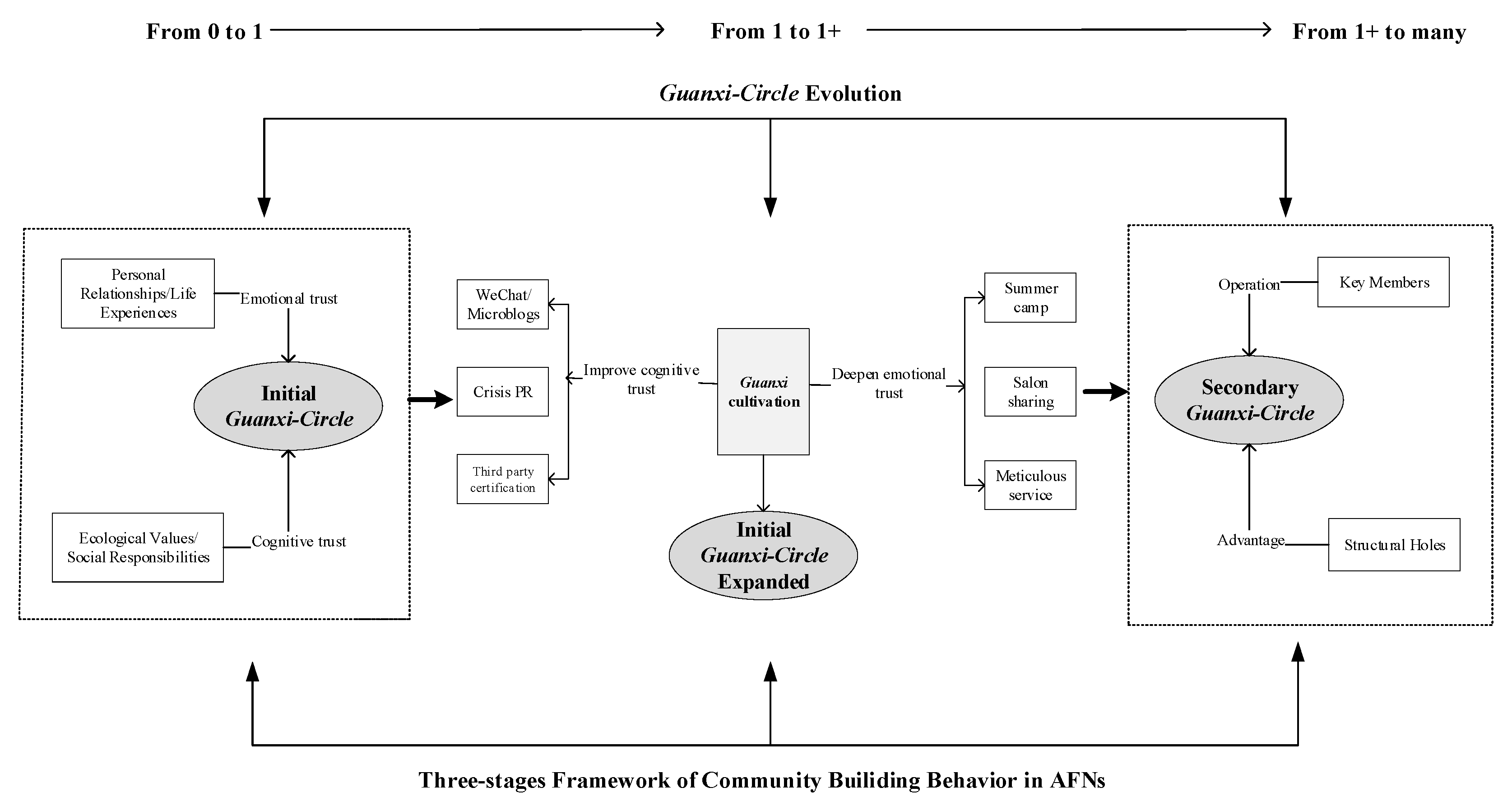

4. Findings

4.1. Building the Initial Guanxi-circle

“You know, unsafe food is caused by the abuse of chemical fertilizers, pesticides and hormones. This farm promises not to use those things. It makes me feel that food safety is guaranteed. Fortunately, I find a place for my children to buy safe food!”(Consumer Ms. Liu from Case A in 2017)

“This farmers’ market is special, different from regular food markets. The vendors are all from suburbs of Shenzhen. They sell seasonal food grown by local farmers, healthy and environmentally friendly. I wrote several articles to recommend them to my readers.”(Health expert Mr. Yu from Case D in 2018)

“In the context of food safety crisis, we should emphasize the safety of food through AFNs. However, AFNs have many goals, such as sustainability, localism, support for rural development, etc. But safe food is the aspect most likely to attract consumers and win trust at present.”(Founder from Case F in 2017)

“As a CSA farm, we promise consumers that we produce in a liangxin way and ensure the safety of our food. Consumers share the risks with us through prepayment, which will enable us not worry about natural risks and market risks. We will do a good job, produce safe food and let time test our promises.”(Founder from Case B in 2018)

“Professor He and I have been friends for many years. Although I don’t know what AFNs are, I don’t think she could do anything wrong. Six years ago (in 2013), she invited me to participate. I agreed without hesitation. Well, friends should help each other.”(Consumer Mr. Zhou from Case E in 2019)

4.2. Strengthening and Expanding the Initial Guanxi-circle

“On WeChat, she often provides updates about what’s happening on the farm, and her updates sometimes fully take over my screen. For example, pig barns and the blue flowers bloom…the children do not want to leave the farm as they are addicted to playing in the mud. We always upvote each other’s WeChat posts. Haha.”(Consumer Ms. Wang from Case A in 2019)

“I learned about this honey from one article published on their WeChat account. The introduction is very detailed. I was deeply moved by their narratives. They were not urging you to buy but just quietly showcased how they were caring for the land and food cautiously and piously. I came to first realized that the Chinese bumblebee is so important.”(Consumer Ms. Liu from Case E in 2020)

“At that time (in 2012), Ms. Shi rushed into the fields angrily and cleared out all the [sprayed] vegetables. But not enough vegetables were left for the delivery in the following week…However, after consumers knew this thing, they were very happy because she kept her promise. And they trusted her even more… thank God she did that.”(Hired Farmer Mr. Ma from Case A in 2018)

“It was wise for her to have done that, which demonstrated her adherence to principles. At that time, AFNs were still new and everyone would be sceptical. That incident cleared people’s doubts and they trusted her more.”(Competitor Mr. Wang who worked in a Beijing’s Agricultural company in 2018)

“I know that they (Case B) has organic certification. Many CSA farms are producing organically. But nobody knows whether they have met organic standards. I also have my own restaurant and have made stable purchase here for two years. The organic certification matters much as my food purchase requires a full certificate.”(Business partner & Consumer Mr. Xia from Case B in 2021)

“The summer camp activities were good. Children were very excited to see lambs and puppies. They also learned about the leaves of okra, pepper and tomato. The mosquitoes were a little bit annoying, but the children were very happy.”(Consumer Ms. Liang from Case A in 2020)

“I’m a nutritionist. There was a moon cake event during the Mid-Autumn Festival. I took the child there and met another nutritionist mother. We discussed a lot on skills and tips for preparing food for children with safe ingredients.”(Consumer Ms. Shang from Case B in 2019)

“I think the salon is very good. Many producers also come to share [their stories]. I really like Mr. Leho and Mr. Rice. They are both cool producers.”(Consumer Ms. Li from Case C in 2020)

“My wife was deeply moved by professor He’s story (Note: Professor He Huili was a deputy county governor in Lankao County, Henan Province who tried to organize farmers to grow rice with reduced usage of chemicals and brought the rice to Beijing for sale in 2005. The story was covered by some influential newspapers as “Professor Selling Rice”.). She introduced her friends to support ecological products.”(Consumer Mr. Hua from Case E in 2018)

“In the millet package I received, there was a thank card that was handwritten by the farmer, very impressive and meticulous.”(Consumer Ms. Meng from Case F in 2019)

4.3. Building a Secondary Guanxi-circle

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rosol, M.; Barbosa, R. Moving beyond direct marketing with new mediated models: Evolution of or departure from alternative food networks? Agri. Hum. Values 2021, 4, 1021–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPES-Food. From Uniformity to Diversity: A Paradigm Shift from Industrial Agriculture to Diversified Agroecological Systems; International Panel of Experts on Sustainable Food Systems: Brussels, Belgium, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Cronin, R.; Halog, A. A unique perspective of materials, practices and structures within the food, energy and water nexus of australian urban alternative food networks. Circ. Econ. Sust. 2021, 2, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, S. Resistance, Grassroots Movements, and Alternative Visions. In Handbook of China and Global Food Security (Elements in Global China); Ching, K.L., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2022; pp. 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, S.; Si, Z.; Schumilas, T.; Chen, A. Organic Food and Farming in China: Top-Down and Bottom-up Ecological Initiatives; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Murdoch, J.; Terry, M.; Banks, J. Quality, nature, and embeddedness: Some theoretical considerations in the context of the food sector. Econ. Geog. 2000, 76, 107–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Social Entrepreneurship & Social Enterprises. 1999. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/cfe/leed/social-economy/social-entrepreneurship.html (accessed on 30 October 2022).

- Ding, D.; Liu, P.; Ravenscroft, N. The new urban agricultural geography of Shanghai. Geoforum 2018, 90, 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.Y.; Michael, B. The transformative power of commoning and alternative food networks. Environ. Polit. 2019, 28, 771–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolavalli, C. Books in review: Alternative food networks: Knowledge, practice, and politics. Gastronomica 2015, 15, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, S.; Hughes, A.; Crang, M.; Zeng, G.; Hocknell, S. Fragmentary embeddedness: Challenges for alternative food networks in Guangzhou, China. J. Rural Stud. 2022, 95, 382–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, Z.; Scott, S. China’s changing food system: Top-down and bottom-up forces in food system transformations. Can. J. Dev. Stud. 2019, 40, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W. Perceived value of a community supported agriculture (CSA) working share. The construct and its dimensions. Appetite 2013, 62, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, Z.; Schumilas, T.; Scott, S. Characterizing alternative food networks in China. Agric. Hum. Values 2015, 32, 299–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, Z.; Li, Y.; Fang, P.; Zhou, L. “One family, two systems”: Food safety crisis as a catalyst for agrarian changes in rural China. J. Rural Stu. 2019, 69, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Qi, G. Bottom-up self-protection responses to China’s food safety crisis. Can. J. Dev. Stud. 2019, 40, 113–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Pan, W.; Yang, W. Characteristics, Health Risk Assessment, and Transfer Model of Heavy Metals in the Soil—Food Chain in Cultivated Land in Karst. Foods 2022, 11, 2802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunham, L.; Freeman, R.E.; Liedtka, J. Enhancing stakeholder practice: A particularized exploration of community. Bus. Ethics Q. 2006, 1, 23–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obst, P.L.; Smith, S.G.; Zinkiewicz, L. An exploration of sense of community, part 3: Dimensions and predictors of psychological sense of community in geographical communities. J. Community Psychol. 2001, 1, 119–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witzling, L.; Shaw, B.R.; Strader, C.; Sedlak, C.; Jones, E. The role of community: CSA member retention. Br. Food J. 2020, 7, 2289–2302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMillan, D.W.; Chavis, D.M. Sense of community: A definition and theory. J. Community Psychol. 1986, 1, 6–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, W.S.Z. Communication practices of professional service providers: Predicting customer satisfaction and loyalty. J. Appl. Commun. Res. 2003, 3, 189–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumilas, T.; Scott, S. Beyond ‘voting with your chopsticks’: Community organizing for safe food in China. Asia Pac. Viewp. 2016, 3, 301–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levkoe, C.Z. The food movement in Canada: A social movement network perspective. J. Peasant Stud. 2014, 41, 385–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whatmore, S.; Pierre, S.; Henk, R. What’s alternative about alternative food networks? Environ. Plan. A 2003, 35, 389–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewicki, R.J.; Edward, C.T.; Nicole, G. Models of interpersonal trust development: Theoretical approaches, empirical evidence, and future directions. J. Man. 2006, 32, 991–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, D. The quality ‘turn’ and alternative food practices: Reflections and agenda. J. Rural Stu. 2003, 19, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martindale, L. ‘I will know it when I taste it’: Trust, food materialities and social media in Chinese alternative food networks. Agric. Hum. Values 2021, 38, 365–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, R.Y.; Si, Z.; Ng, C.N.; Scott, S. The transformation of trust in China’s alternative food networks: Disruption, reconstruction, and development. Ecol. Soc. 2015, 20, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAllister, D.J. Affect- and cognition-based trust as foundations for interpersonal cooperation in organizations. Acad. Manag. J. 1995, 38, 24–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjærnes, U. Trust and distrust: Cognitive decisions or social relations? J. Risk Res. 2006, 9, 911–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, J.D.; Andrew, W. Trust as a social reality. Soc. For. 1985, 63, 967–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W. The cognitive structure of consumer value of agricultural labor share supported by community: Application of method-purpose chain. Agric. Technol. Econ. 2012, 9, 84–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Tan, S. Impact of social media apps on producer–member relations in China’s community supported agriculture. Can. J. Dev. Stud. 2019, 40, 97–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krul, K.; Peter, H. Alternative approaches to food: Community supported agriculture in urban China. Sustainability 2017, 9, 844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Chen, C. On the intricacies of the Chinese Guanxi: A process model of Guanxi development. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2004, 21, 305–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Li, Y.; Zhou, L. A Consociation Model: Organization of Collective Entrepreneurship for Village Revitalization. Systems 2022, 10, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.Y.; Philip, L.D. Guanxi, trust, and long-term orientation in Chinese business markets. J. Intern. Market. 2005, 13, 28–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alston, J.P. Wa, Guanxi, and Inhwa: Managerial principles in Japan, China, and Korea. Bus. Horiz. 1989, 32, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, Y. Guanxi and the allocation of urban jobs in China. China Q. 1994, 140, 971–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, K.M. Building theories from case study research. Aca. Man. Rev. 1989, 14, 532–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gioia, D.A.; Corley, K.G.; Hamilton, A.L. Seeking qualitative rigor in inductive research: Notes on the Gioia Methodology. Organ. Res. Methods 2013, 16, 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granovetter, M. Economic action and social structure: The problem of embeddedness. Am. J. Sociol. 1985, 91, 481–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burt, R.S. Structural holes. In Social Stratification; Routledge: London, UK, 2018; pp. 659–663. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Sun, Y.; Jing, J.; Wang, E. Institutional Trust as a Protective Factor during the COVID-19 Pandemic in China. Behav. Sci. 2022, 12, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Case A | Case B | Case C | Case D | Case E | Case F | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Types | CSA Farm | CSA Farm | Farmers’ Market | Farmers’ Market | Social Enterprise | Social Enterprise |

| Founder | Female, PhD, opinion leader, Socialist, studied abroad | Male, entrepreneur, engaged in finance and real estate, 10 years of experience in organic agriculture | Female, Journalist, Opinion Leader | Female, entrepreneur, Christians leader with strong integrity and concern for public interest | Organized by Professor He, cares about food safety and rural development | Male, entrepreneur, agriculture science expert, has rich CSA experience |

| Location | Beijing North China | Huizhou South China | Beijing North China | Shenzhen South China | Beijing North China | Guangzhou South China |

| Team Numbers | 21 | 40 | 5 | 6 | 18 | 30 |

| Sources of start-up capital | Self-raised +10 shareholders | 108 shareholders | ——— | Sponsors and four sponsoring agencies | Institutional funding | Self-raised |

| Operating conditions | Established in 2012, 2014 in balance, annual turnover 5 million Chinese Yuan, 600 consumers | Established in 2013, has organic certification, 2000 consumers, rapid development | Founded in 2010, held twice a week, 40 cooperative farms and enterprises | Established in 2012, opens once a month, 20 cooperative farms | Established in 2006, organized loosely, slow development, 7 cooperatives farmers | Established in 2008, 20 farming partners, more than 5000 customers, turnover of 6 million Chinese Yuan |

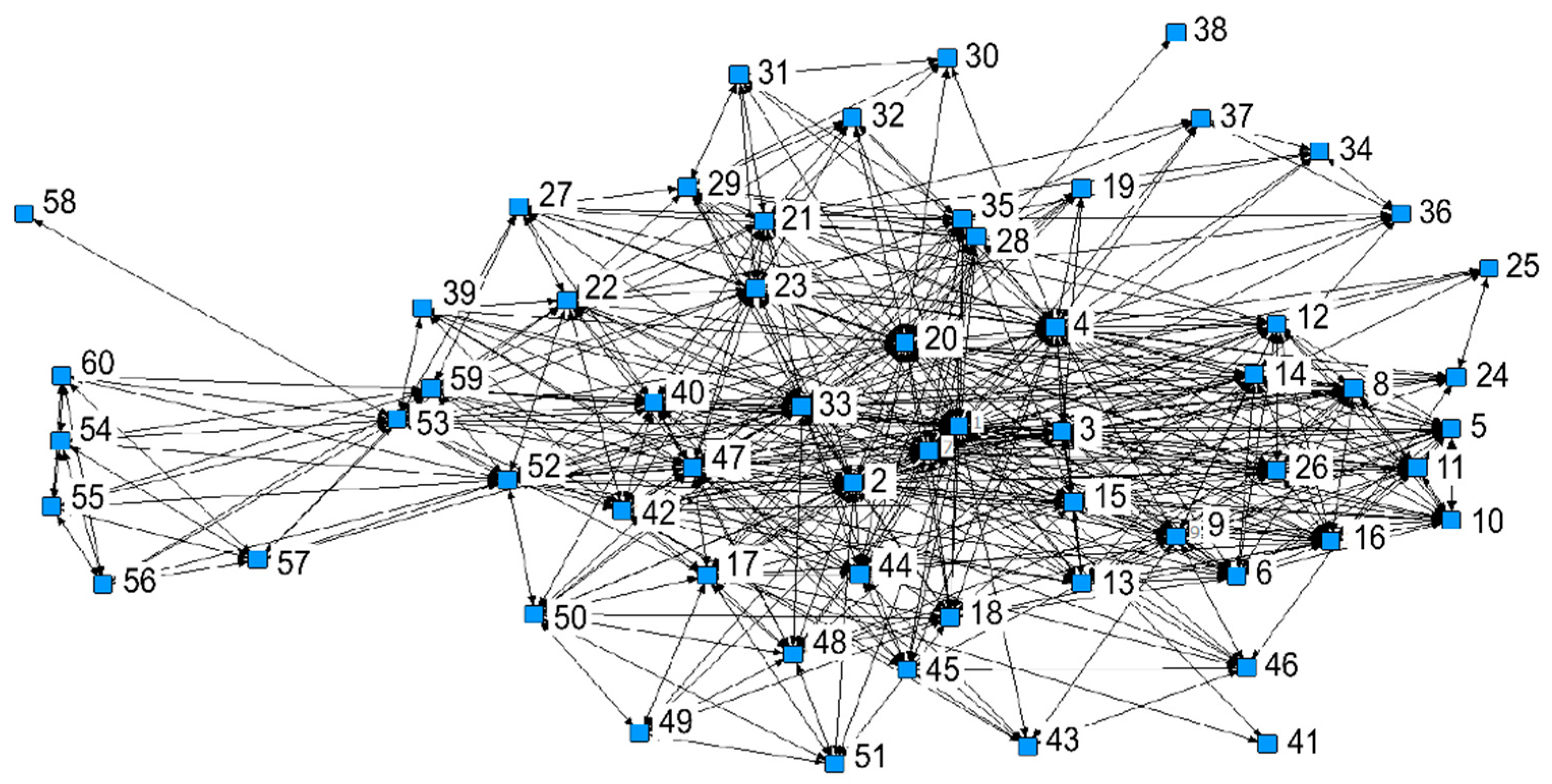

| Num.1 | Num.2 | Num.3 | Num.4 | Num.5 | … | Num.59 | Num.60 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Num.1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | … | 1 | 0 |

| Num.2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | … | 1 | 0 |

| Num.3 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | … | 1 | 0 |

| Num.4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | … | 0 | 0 |

| Num.5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | … | 0 | 0 |

| … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … |

| Num.59 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | … | 1 | 0 |

| Num.60 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | … | 1 | 0 |

| Number of Factions | Members in Each Faction |

|---|---|

| 1 | 1–16, 18, 20, 26 |

| 2 | 17, 19, 24, 25, 33, 39–47 |

| 3 | 38, 41, 52–60 |

| 4 | 21–23, 27–37 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, Y.; Si, Z.; Miao, Y.; Zhou, L. How Does the Concept of Guanxi-circle Contribute to Community Building in Alternative Food Networks? Six Case Studies from China. Behav. Sci. 2022, 12, 432. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12110432

Li Y, Si Z, Miao Y, Zhou L. How Does the Concept of Guanxi-circle Contribute to Community Building in Alternative Food Networks? Six Case Studies from China. Behavioral Sciences. 2022; 12(11):432. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12110432

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Yanyan, Zhenzhong Si, Yuxin Miao, and Li Zhou. 2022. "How Does the Concept of Guanxi-circle Contribute to Community Building in Alternative Food Networks? Six Case Studies from China" Behavioral Sciences 12, no. 11: 432. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12110432

APA StyleLi, Y., Si, Z., Miao, Y., & Zhou, L. (2022). How Does the Concept of Guanxi-circle Contribute to Community Building in Alternative Food Networks? Six Case Studies from China. Behavioral Sciences, 12(11), 432. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12110432