Implementing Trauma Informed Care in Human Services: An Ecological Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

“A program, organization, or system that is trauma-informed realizes the widespread impact of trauma and understands potential paths for recovery; recognizes the signs and symptoms of trauma in clients, families, staff, and others involved with the system; and responds by fully integrating knowledge about trauma into policies, procedures, and practices, and seeks to actively resist re-traumatization”[2] (p. 9).

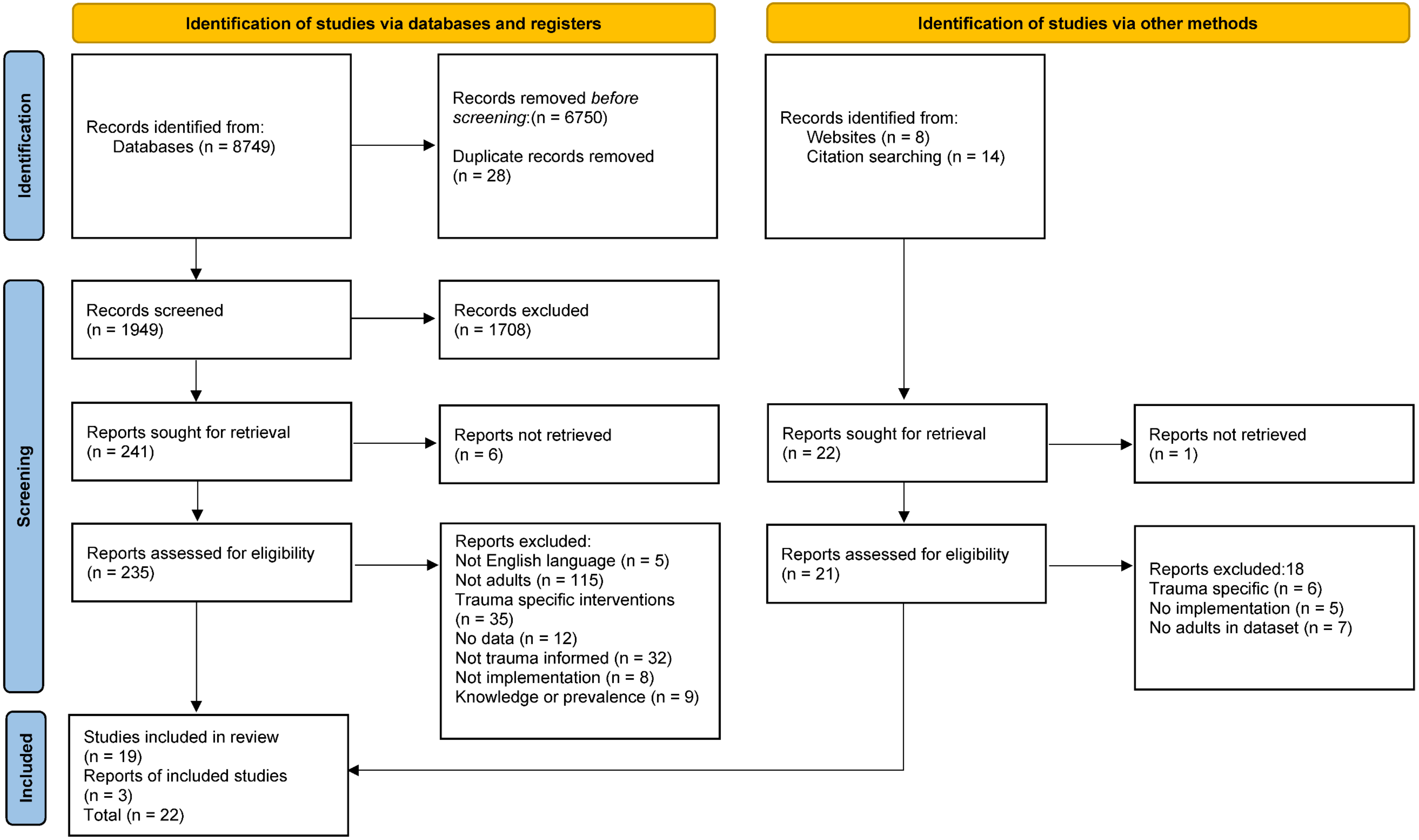

2. Materials & Methods

3. Results

3.1. Macro System

3.2. Meso System

3.3. Micro System

3.4. Quality of Studies

3.5. Review of Outcome Measures

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications for Practice, Policy, and Research

4.2. Limitations

4.3. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sweeney, A.; Filson, B.; Kennedy, A.; Collinson, L.; Gillard, S. A paradigm shift: Relationships in trauma-informed mental health services. BJPsych Adv. 2018, 24, 319–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, M.; Fallot, R.D. Envisioning a trauma-informed service system: A vital paradigm shift. N. Dir. Ment. Health Serv. 2001, 89, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahon, D. Trauma Responsive Organisations: The Trauma Ecology Model; Emerald Publications: Bingley, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). “SAMHSA’s Concept of Trauma and Guidance for a Trauma-Informed Approach, US Department of Health and Human Services, USA (HHS Publication No. (SMA) 14–4884. 2014. Available online: Ncsacw.acf.hhs.gov/userfiles/files/SAMSHA_Trauma.pdf (accessed on 2 July 2022).

- Felitti, V.J.; Anda, R.F.; Nordenberg, D.; Williamson, D.F.; Spitz, A.M.; Edwards, V.; Koss, M.P.; Marks, J.S. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. Am. J. Prev. Med. 1998, 14, 245–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Read, J.; Hammersley, P.; Rudegeair, T. Why, when and how to ask about childhood abuse. Adv. Psychiatr. Treat. 2007, 13, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shevlin, M.; Houston, J.E.; Dorahy, M.J.; Adamson, G. Cumulative traumas and psychosis: An analysis of the national comorbidity survey and the British Psychiatric Morbidity Survey. Schizophr. Bull. 2008, 34, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benjet, C.; Bromet, E.; Karam, E.G.; Kessler, R.C.; McLaughlin, K.A.; Ruscio, A.M.; Shahly, V.; Stein, D.J.; Petukhova, M.; Hill, E.; et al. The epidemiology of traumatic event exposure worldwide: Results from the World Mental Health Survey Consortium. Psychol. Med. 2016, 46, 327–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleber, R.J. Trauma and public mental health: A focused review. Front. Psychiatry 2019, 10, 451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly-Irving, M.; Delpierre, C. A Critique of the Adverse Childhood Experiences Framework in Epidemiology and Public Health: Uses and Misuses. Soc. Pol. Soc. 2019, 18, 445–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, W.R.; Dietz, W.H. A New Framework for Addressing Adverse Childhood and Community Experiences: The Building Community Resilience Model. Acad. Pediatr. 2017, 17, S86–S93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phipps, M.; Molloy, L.; Visentin, D. Prevalence of Trauma in an Australian Inner City Mental Health Service Consumer Population. Commun. Ment. Health J. 2019, 55, 487–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Child Abuse and Neglect Cost the United States $124 Billion. 2012. Available online: http://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2012/p0201_child_abuse.html (accessed on 15 July 2022).

- Hughes, K.; Bellis, M.A.; Hardcastle, K.A.; Sethi, D.; Butchart, A.; Mikton, C.; Jones, L.; Dunne, M.P. The effect of multiple adverse childhood experiences on health: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Public Health 2017, 2, e356–e366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellis, M.A.; Hughes, K.; Ford, K.; Rodriguez, G.R.; Sethi, D.; Passmore, J. Life course health consequences and associated annual costs of adverse childhood experiences across Europe and North America: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Public Health 2019, 4, e517–e528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magruder, K.M.; McLaughlin, K.A.; Borbon, D.L.E. Trauma is a public health issue. Eur. J. Psychotraumatolog. 2017, 9, 1375338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esaki, N.; Larkin, H. Prevalence of adverse childhood experiences (ACE) among child service providers. Fam. Soc. 2013, 94, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bride, B.E.; Hatcher, S.S.; Humble, M.N. Trauma training, trauma practices, and secondary traumatic stress among substance abuse counselors. Traumatology 2009, 15, 96–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson-Keilig, R.A. Secondary traumatic stress and disruptions to interpersonal functioning among mental health therapists. J. Interpers. Violence 2014, 29, 1477–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahon, D. Trauma-informed servant leadership in health and social care settings. Ment. Health Soc. Inc. 2021, 25, 306–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloom, S. Parallel Processes and Trauma-Organized Systems. In Destroying Sanctuary: The Crisis in Human Service Delivery Systems; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, M.; Fallot, R.D. Using Trauma Theory to Design Service Systems; Jossey-Bass/Wiley: Francisco, CA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Hopper, E.K.; Bassuk, E.L.; Olivet, J. Shelter from the Storm: Trauma-Informed Care in Homelessness Services Settings. Open Health Serv. Policy J. 2010, 3, 80–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Child Traumatic Stress Network. Creating Trauma Informed Systems. 2012. Available online: http://www.nctsn.org/resources/topics/creating-trauma-informed-systems (accessed on 5 July 2022).

- Jericho, B.; Luo, A.; Berle, D. Trauma-focused psychotherapies for post-traumatic stress disorder: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Acta. Psychiatr. Scand. 2022, 145, 132–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Y.; Cipriani, A.; Teng, T.; Del Giovane, C.; Zhang, Y.; Weisz, J.R.; Li, X.; Cuijpers, P.; Liu, X.; Barth, J.; et al. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of psychotherapies for post-traumatic stress disorder in children and adolescents: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Evid. Based. Ment. Health 2021, 24, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fixsen, D.; Naoom, S.; Blase, K.; Friedman, R.; Wallace, F. Implementation Research: A Synthesis of the Literature; University of South Florida, Louis de la Parte Florida Mental Health Institute, National Implementation Research Network: Tamps, FL, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Fixsen, D.L.; Blase, K.A.; Naoom, S.F.; Wallace, F. Core Implementation Components. Res. Soc. Work Pract. 2009, 19, 531–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, W.R.; Sorensen, J.L.; Selzer, J.A.; Brigham, G.S. Disseminating evidence-based practices in substance abuse treatment: A review with suggestions. J. Subst. Abus. Treat. 2006, 31, 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, D.H.; Adam, T.; Alonge, O.; Agyepong, I.A.; Tran, N. Implementation research: What it is and how to do it. BMJ Clin. Res. Ed. 2013, 347, f6753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avery, J.C.; Morris, H.; Galvin, E.; Misso, M.; Savaglio, M.; Skouteris, H. Systematic Review of School-Wide Trauma-Informed Approaches. J. Child Adolesc. Trauma 2020, 14, 381–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, C.; Klas, A.; Cox, R.; Bergmeier, H.; Avery, J.; Skouteris, H. Systematic review of organisation-wide, trauma-informed care models in out-of-home care (OoHC) settings. Health Soc. Care Commun. 2019, 27, e10–e22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowenthal, A. Trauma-informed care implementation in the child- and youth-serving sectors: A scoping review. Int. J. Child Adolesc. Resil. 2020, 7, 178–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, M.T.; Rajić, A.; Greig, J.D.; Sargeant, J.M.; Papadopoulos, A.; McEwen, S.A. A scoping review of scoping reviews: Advancing the approach and enhancing the consistency. Res. Synth. Methods 2014, 5, 371–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munn, Z.; Peters, M.; Stern, C.; Tufanaru, C.; McArthur, A.; Aromataris, E. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2018, 18, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.; Colquhoun, H.; Kastner, M.; Levac, D.; Ng, C.; Sharpe, J.P.; Wilson, K.; et al. A scoping review on the conduct and reporting of scoping reviews. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2016, 16, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. Toward an experimental ecology of human development. Am. Psychol. 1977, 32, 513–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, M.D.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H.; McInerney, P.; Parker, D.; Soares, C.B. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int. J. Evid. Based Healthc. 2015, 13, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ Clin. Res. Ed. 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrard, J. Health Sciences Literature Review Made Easy: The Matrix Method; Jones and Bartlett Learning: Burlington, MA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Shier, M.L.; Turpin, A. Trauma-Informed Organizational Dynamics and Client Outcomes in Concurrent Disorder Treatment. Res. Soc. Work Pract. 2022, 32, 92–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blazejewski, L.A. Nurse Perspectives of Trauma-Informed Care. Ph.D. Thesis, Walden University, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2021; p. 11257. Available online: https://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/dissertations/11257 (accessed on 17 September 2022).

- Nanson, S. How California Became ACEs Aware: A Case Study Examining Program Implementation During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Ph.D. Thesis, The Claremont Graduate University, School of Community and Global Health, Claremont, CA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Piper, K.; Schiff, J.; Riddick, C.; Getachew, B.; Farber, E.; Kalokhe, A.; Sales, J.W. Barriers and facilitators to implementation of trauma support services at a large HIV treatment center in the Southern United States. AIDS Care 2021, 33, 316–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robey, N.; Margolies, S.; Sutherland, L.; Rupp, C.; Black, C.; Hill, T.; Baker, C.N. Understanding staff- and system-level contextual factors relevant to trauma-informed care implementation. Psychol. Trauma Theory Res. Pract. Policy 2021, 13, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, R. Program Domains of Trauma-Informed Practice Associated with Client Perception of Care and Staff Perceived Organizational Support: A Study of Women’s Substance Use Programs Utilizing Qualitative Comparative Analysis. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley, A. A Qualitative Evaluation of the Nelson Trust Griffin Programme. Ph.D. Thesis, Walden University, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Chalakani, T.A. Employee Resistance to Change during the Implementation of Trauma-Informed Care. Ph.D. Thesis, Walden University, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2020; p. 8446. [Google Scholar]

- Hales, T.W.; Green, S.A.; Bissonette, S.; Warden, A.; Diebold, J.; Koury, S.P.; Nochajski, T.H. Trauma-Informed Care Outcome Study. Res. Soc. Work Pract. 2019, 29, 529–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusmaul, N.; Wolf, M.R.; Sahoo, S.; Green, S.A.; Nochajski, T.H. Client Experiences of Trauma-Informed Care in Social Service Agencies. J. Soc. Service Res. 2019, 45, 589–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matlin, S.L.; Champine, R.B.; Strambler, M.J.; O’Brien, C.; Hoffman, E.; Whitson, M.; Kolka, L.; Tebes, J.K. A Community’s Response to Adverse Childhood Experiences: Building a Resilient, Trauma-Informed Community. Am. J. Commun. Psychol. 2019, 64, 451–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sundborg, S.A. Knowledge, principal support, self-efficacy, and beliefs predict commitment to trauma-informed care. Psychol. Trauma Theory Res. Pract. Policy 2019, 11, 224–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unick, G.J.; Bassuk, E.L.; Richard, M.K.; Paquette, K. Organizational trauma-informed care: Associations with individual and agency factors. Psychol. Serv. 2019, 16, 134–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubay, L.; Burton, R.; Epstien, M. Early Adopters of Trauma-Informed Care: An Implementation Analysis of the Advancing Trauma-Informed Care Grantees. 2018. Unpublished. Available online: https://www.chcs.org/resource/early-adopters-of-trauma-informed-care-an-implementation-analysis-of-the-advancing-trauma-informed-care-grantees/ (accessed on 17 September 2022).

- Bruce, M.M.; Kassam-Adams, N.; Rogers, M.; Anderson, K.M.; Sluys, K.P.; Richmond, T.S. Trauma Providers’ Knowledge, Views, and Practice of Trauma-Informed Care. J. Trauma Nurs. 2018, 25, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ward-Lasher, A.; Messing, J.; Stein-Seroussi, J. Implementation of Trauma-Informed Care in a Housing First Program for Survivors of Intimate Partner Violence: A Case Study. Adv. Soc. Work 2017, 18, 202–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isobel, S.; Edwards, C. Using trauma informed care as a nursing model of care in an acute inpatient mental health unit: A practice development process. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2017, 26, 88–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keesler, J.M.; Isham, C. Trauma-Informed Day Services: An Initial Conceptualization and Preliminary Assessment. J. Policy Pract. Intellect. Disabil. 2017, 14, 164–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hales, T.W.; Nochajski, T.; Green, S. An Association between Implementing Trauma-Informed Care and Staff Satisfaction. Adv. Soc. Work 2017, 18, 300–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damian, A.J.; Gallo, J.; Leaf, P.; Mendelson, T. Organizational and provider level factors in implementation of trauma-informed care after a city-wide training: An explanatory mixed methods assessment. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2017, 17, 750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keesler, J.M. Trauma-informed Day Services for Individuals with Intellectual/Developmental Disabilities: Exploring Staff Understanding and Perception within an Innovative Programme. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. JARID 2016, 29, 481–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirst, M.; Aery, A.; Matheson, F.I.; Stergiopoulos, V. Provider and Consumer Perceptions of Trauma Informed Practices and Services for Substance Use and Mental Health Problems. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2017, 15, 514–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overstreet, S.; Chafouleas, S. Trauma-informed schools: Introduction to the special issue. Sch. Ment. Health 2016, 8, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, T. Children Exposed to Violence: A Developmental Trauma Informed Response for the Criminal Justice System. J. Child Adolesc. Trauma 2016, 9, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, E.M. Diffusion of Innovations; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Aarons, G.A.; Hurlburt, M.; Horwitz, S.M. Advancing a conceptual model of evidence-based practice implementation in public service sectors. Adm. Policy Ment. Health 2011, 38, 4–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durlak, J.A.; DuPre, E.P. Implementation matters: A review of research on the influence of implementation on program outcomes and the factors affecting implementation. Am. J. Commun. Psychol. 2008, 41, 327–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bryson, S.; Gauvin, E.; Jamieson, A.; Rathgeber, M.; Faulkner–Gibson, L.; Bell, S.; Davidson, J.; Russel, J.; Burke, S. What are effective strategies for implementing trauma-informed care in youth inpatient psychiatric and residential treatment settings? A realist systematic review. Int. J. Ment. Health Syst. 2017, 11, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, R.F.; Lang, J. A Critical Look At Trauma-Informed Care Among Agencies and Systems Serving Maltreated Youth and Their Families. Child Maltreat 2016, 21, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackmore, R.; Boyle, J.A.; Fazel, M.; Ranasinha, S.; Gray, K.M.; Fitzgerald, G.; Misso, M.; Gibson-Helm, M. The prevalence of mental illness in refugees and asylum seekers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2020, 17, e1003337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henkelmann, J.; Best, S.D.; Deckers, C.; Jensen, K.; Shahab, M.; Elzinga, B.; Molendijk, M. Anxiety, depression and post-traumatic stress disorder in refugees resettling in high-income countries: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BJPsych Open 2020, 6, E68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Im, H.; Swan, L.E.T. Working towards culturally responsive trauma-informed care in the refugee resettlement process: Qualitative inquiry with refugee-serving professionals in the United States. Behav. Sci. 2021, 11, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, L.S.; Rodgers, G. Cultural competence in refugee service settings: A scoping review. Health Equity 2021, 5, 124–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esaki, N.; Reddy, M.; Bishop, C.T. Next Steps: Applying a Trauma-Informed Model to Create an Anti-Racist Organizational Culture. Behav. Sci. 2022, 12, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eddie, D.; Hoffman, L.; Vilsaint, C.; Abry, A.; Bergman, B.; Hoeppner, B.; Weinstein, C.; Kelly, J.F. Lived Experience in New Models of Care for Substance Use Disorder: A Systematic Review of Peer Recovery Support Services and Recovery Coaching. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, A.J.; Simmons, M.B. A systematic review of the attributes and outcomes of peer work and guidelines for reporting studies of peer interventions. Psychiatr. Serv. 2018, 69, 961–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, S.; Foster, R.; Marks, J.; Morshead, R.; Goldsmith, L.; Barlow, S.; Sin, J.; Gillard, S. The effectiveness of one-to-one peer support in mental health services: A systematic review and metaanalysis. BMC Psychiatry 2020, 20, 534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahon, D. Servant leadership informed trauma peer support. Ment. Health Soc. Incl. 2021, 25, 366–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahon, D. A systematic scoping review of interventions delivered by peers to support the resettlement of refugees and asylum seekers. Ment. Health Soc. Incl. 2022, 26, 206–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leathers, S.J.; Spielfogel, J.E.; Blakey, J.; Christian, E.; Atkins, M.S. The Effect of a Change Agent on Use of Evidence-Based Mental Health Practices. Adm. Policy Ment. Health 2016, 43, 768–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purtle, J. Systematic review of evaluations of trauma-informed organizational interventions that include staff trainings. Trauma Violence Abus. 2020, 21, 725–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damschroder, L.J.; Aron, D.C.; Keith, R.E.; Kirsh, S.R.; Alexander, J.A.; Lowery, J.C. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: A consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement. Sci. 2009, 4, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grol, R.P.; Bosch, M.C.; Hulscher, M.E.; Eccles, M.P.; Wensing, M. Planning and studying improvement in patient care: The use of theoretical perspectives. Milbank Q. 2007, 85, 93–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogers, E.M.; Singhal, A.; Quinlan, M.M. Diffusion of Innovations. In An Integrated Approach to Communication Theory and Research; Routledge: London, UK, 2014; pp. 432–448. [Google Scholar]

- International Classification of Diseases, Eleventh Revision (ICD-11), World Health Organization (WHO) 2019/2021. Licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 3.0 IGO Licence (CC BY-ND 3.0 IGO). Available online: https://icd.who.int/browse11 (accessed on 12 July 2022).

- Gustafson, D.H.; Quanbeck, A.R.; Robinson, J.M.; Ford, J.H., II; Pulvermacher, A.; French, M.T.; McConnell, K.J.; Batalden, P.B.; Hoffman, K.A.; McCarty, D. Which elements of improvement collaboratives are most effective? A cluster-randomized trial. Addiction 2013, 108, 1145–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, W.R.; Yahne, C.E.; Moyers, T.B.; Martinez, J.; Pirritano, M. A randomized trial of methods to help clinicians learn motivational interviewing. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2004, 72, 1050–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Champine, R.B.; Lang, J.M.; Nelson, A.M.; Hanson, R.F.; Tebes, J.K. Systems Measures of a Trauma-Informed Approach: A Systematic Review. Am. J. Commun. Psychol. 2019, 64, 418–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braithwaite, J.; Churruca, K.; Long, J.C.; Ellis, L.A.; Herkes, J. When complexity science meets implementation science: A theoretical and empirical analysis of systems change. BMC Med. 2018, 16, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhalgh, T.; Papoutsi, C. Studying complexity in health services research: Desperately seeking an overdue paradigm shift. BMC Med. 2018, 16, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharek, D.; Lally, N.; Brennan, C.; Higgins, A. “These are people just like us who can work”: Overcoming clinical resistance and shifting views in the implementation of Individual Placement and Support (IPS). Adm. Policy Ment. Health 2022, 49, 848–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| PCC | Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Language | English | Any non-English article |

| Type of article | Journal articles peer reviewed with dataset Grey literature with dataset Reports or evaluations with dataset Dissertations with dataset | Review articles Case studies without data Editorials Policy documents Systematic review/meta-analyses |

| Population | Organizations or communities providing services to adults, or studies where services provided to adults make up part of the dataset | Where data is reporting on service providers exclusively working with children or adolescents or families |

| Context | Any organisation or community study where trauma informed care as a universal method of service delivery is the main aim | Medical trauma in hospitals or other settings. |

| Concept | Has some mention of employee, or service user experience of TIC in the context of implementation, or organizational considerations of TIC | Trauma specific psychotherapy interventions, or interventions described only as PTSD, diagnostic assessment, or prevalence articles Research reporting on knowledge, attitudes, or experience of TIC without analysis of implications for implementation/organizational considerations TIC training without implementation considerations for TIC in adult services |

| Study | Location | Article Type | Target Group | Sample Size | Study Design | Intervention or Research Question Being Studied | Outcome Measures | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shier & Turpin (2022) [44] | Canada | Journal article | Dual diagnosis in residential treatment | (N = 172) | Multisite quantitative survey repeated measures | To test an empirical model of the effects of a trauma-informed organizational environment on service user outcomes in the context of concurrent disorder treatment | GAINs-SS. Intrapersonal Social Outcomes Development Scale; The Trauma-Informed Organizational Environment Scale | Service users at this organization had high overall trauma-informed organizational experiences, where staff engaged in behaviours that supported the development of safety, trust, choice, collaboration, and empowerment within concurrent disorder treatment programs. |

| Blazejewski (2021) [45] | USA | Dissertation | Nurses’ attitudes and beliefs about implementing TIC in disability | (N = 15) | Qualitative interviews | Theory of Planned Behaviour on implementing TIC | N/A | Four themes: nurses feeling empowered to avoid inadvertent patient re- traumatization, enhanced empathy towards patients, uncertainty about referents’ use of trauma-informed care, and the essential importance of being equipped and prepared |

| Nanson (2021) [46] | USA | Dissertation | The State of California | (N = 31) | Case Study qualitative | ACE Aware Initiative | N/A | Various themes related to implementation facilitators and barriers |

| Piper et al. (2021) [47] | USA | Journal article | Stakeholders at service for HIV | (N = 94) | Mixed methods survey and interviews | Barriers and facilitators to implementing TIC | Survey adapted from Trauma-informed Organizational Toolkit | Results highlighted the availability of several trauma services, including psychotherapy and support groups, but also revealed the absence of provider training on how to respond to patient trauma needs. Identified gaps in TIC services included written safety and crisis prevention plans, patient education on traumatic stressors, and opportunities for creative expression. Providers and staff supported implementation of trauma support services and employee trainings but expressed several concerns including resource and skill deficiencies. |

| Robey et al. (2021) [48] | USA | Journal article | Various mental and human health services | (N = 760) | Quantitative survey | Understanding Staff- and System-Level Contextual Factors Relevant to Trauma-Informed Care Implementation | The Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) | The attributes of the individuals implementing TIC and the implementation climate of the organization played the most central roles. identified available resources and the strength and quality of the evidence underpinning the intervention as important contextual factors for TIC implementation. |

| Yoon (2021) [49] | Canada | Dissertation | Women’s substance use programmes | (N = 9) Agencies | Case Study | Client perception of care and staff perceived organizational support | Creating Cultures of Trauma-Informed Care Program Fidelity Scale Version 1.3 (CCTIC) Ontario Perception of Care –MentalHealth and Addictions OPOC-MHA Survey of Perceived Organizational Support Scale (SPOS) Creating Cultures of Trauma Informed Care (CCTIC) Fidelity Measure | Although the CCTIC has utility to inform program planning and implementation for trauma-informed services, it may be challenged as a tool to evaluate the extent to which program domains are associated with client perception of care and staff perceived support. |

| Bradley et al. (2020) [50] | United Kingdom | Report | Bridge Water Womens Centre | (N = 12) | Qualitative interviews and focus group | An evaluation of a woman’s TIC programme | N/A | The findings of this evaluation highlighted some areas of good practice within the implementation of trauma-informed practice. These included embedding trauma awareness within hiring practices and the prioritisation of staff training and development to ensure that staff can better recognise and respond to the needs of women with histories of trauma |

| Chalakani (2020) [51] | USA | Disertation | Leadership experience of resistance during implementation | (N = 4) | Case Study | Leadership experience of employee resistance to change during the implementation of trauma-informed care | N/A | A change management process, effective use of available staff satisfaction data, and improved communication can lessen the experience of resistance. Trauma-informed care is seen as a positive change that enhances the workplace. Thus, its implementation is an opportunity for leadership to engage the workforce and the organization’s clients |

| Hales et al. (2019) [52] | USA | Journal article | Residential substance use | (N = 70) | Longitudinal with three collection points | To operationalize the processes, an agency can take to become trauma informed and assesses the impact of a multiyear TIC implementation project on organizational climate, procedures, staff and resident satisfaction, and client retention in treatment. | Trauma-Informed Climate Scale (TICS); Trauma-Informed Organizational Self-Assessment; Staff satisfaction was assessed using a 24-item instrument created internally; Client satisfaction was assessed using a dichotomous (yes or no) 42-item instrument created by the agency that assessed client satisfaction at 30 days, 90 days, and at discharge; Client retention was operationalized as client-planned discharge status | Following TIC implementation, there were positive changes in each of the five outcomes assessed. Workplace satisfaction, climate, and procedures improved by moderate to large effect sizes, while client satisfaction and the number of planned discharges improved significantly. |

| Kusmaul et al. (2019) [53] | USA | Journal article | Various health and human agencies | (N = 26) | Qualitative interviews | To understand how clients experience trauma-informed care services and implementation challenges. | N/A | The results of the study suggest that clients’ experience of these concepts was shaped by the actions of other clients, and these experiences were either mitigated or hindered by actions of the agency employees. Agency policies either supported or enhanced their experiences as well. The results also suggest that it was challenging for agencies to provide for all of the trauma-informed care (TIC) concepts at the same time |

| Matlin et al. (2019) [54] | USA | Journal articles | A whole community approach to TIC | Various N depending on different methodologies | Mixed-methods, multi-level design to examine PTICC processes at various times over its two-year initial implementation phase | A Tripartite Population Health Model of Trauma-Informed Practice: initiative—Pottstown Trauma-Informed Community Connection (PTICC) | Trauma Training Survey; Trauma Training Survey; Community Partner Survey; Attitudes Related to Trauma-Informed Care; Trauma System Readiness Tool; Levels of Collaboration Scale | The results show that moving forward the community is well-positioned to establish stronger inter-agency and system supports for trauma-informed practice in the service system and in the broader community. |

| Sundborg (2019) [55] | USA | Journal article | Particpants working in human services variables that predict affective commitment to TIC including foundational knowledge, principal support, self-efficacy, and beliefs about trauma | (N = 118) | Cross-sectional survey | The variables that predict affective commitment to TIC including foundational knowledge, principal support, self-efficacy, and beliefs about trauma | Affective Commitment Subscale; measure of foundational knowledge about TIC was created for this study; The Beliefs about Trauma Scale was created for the current study; Self-efficacy was measured using the Readiness for Organizational Change Scale (ROC); Principal support was measured using a six-item subscale from the Organizational Change Recipients’ Beliefs Scale (OCRBS) | Altogether, the model explained 65% of the variance in affective commitment to TIC |

| Unick et al. (2019) [56] | USA | Journal article | The relationship of individual and agency characteristics to the level of organizational TIC | (N = 345) | Quantitative survey | The relationship of individual and agency characteristics to the level of organizational TIC | Level of organizational trauma-informed care was measured using the TICOMETER | Weak relationships between individual factors and TICOMETER scores and stronger associations for agency-level factors. These included agency type, time since last trauma training, and involvement of service users. These findings highlight the importance of robust cultural changes, service user involvement at all levels of the organization, flattening power differentials, and providing ongoing experiential training. |

| Duby et al. (2018) [57] | USA | Report | Agencies who received funding to implement TIC | (N = 69) (N = 6) agencies | Qualitative interviews | An implementation analysis of efforts pursued by organizations participating in a grant program | N/A | A range of outcomes reported on; Changing organizational culture; Training and hiring; Promoting staff self-care; Screening for early adversity and trauma; Delivering trauma-responsive services; Involving patients; Facilitators and barriers |

| Bruce et al. (2018) [58] | USA | Journal article | Medical employees working in trauma centres | (N = 147) | Qualitative interviews | To examine health care provider knowledge, attitudes, practices, competence, and perceived barriers to implementation of TIC. | N/A | All participants rated the following as significant barriers to providing basic TIC: time constraints, need of training, confusing information about TIC, and worry about re-traumatizing patients. Self-rated competence was the most consistent predictor of providers’ reported use of specific TIC practices |

| Ward-Lasher et al. (2017) [59] | USA | Journal article | Homeless women experiencing domestic violence in Housing First | (N = 7) | Case study mixed methods | How practitioners and administrators implement trauma-informed care in a Housing First program for IPV survivors | Secondary survey data from the agency | Trauma-informed care principles and the Housing First model were found to be complementary. The majority of clients in this program retained housing up to 3-months after services ended and increased their safety and knowledge of domestic violence. Combining Housing First with trauma-informed care may increase success for survivors of IPV. |

| Isober & Edwards (2017) [60] | Australia | Journal articles | Nurses implementing TIC | (N = 5) | Mixed method Case Study | A nursing workforce practice development process to implement Trauma Informed Care as an inpatient model of mental health nursing care | N/A | While there are differing strategies for implementation, there is scope for mental health nurses to take on Trauma Informed Care as a guiding philosophy, a model of care or a practice development project within all of their roles and settings in order to ensure that it has considered, relevant and meaningful implementation. The principles of Trauma Informed Care may also offer guidance for managing workforce stress and distress associated with practice change. |

| Kessler & Isham (2017) [61] | USA | Journal article | Day service for disabilities | (N = 37) | Mixed method evaluation | To provide an initial conceptualization and preliminary assessment of TIC within IDD services in order to understand its impact among individuals and staff | Trauma Informed Care Measure | Three major categories emerged from the qualitative data (making a difference, recognizing progress and compromising factors), illuminating staff satisfaction with work experiences, individuals’ progress, and factors that challenged fidelity to TIC. |

| Hales et al. (2017) [62] | USA | Journal article | Mental health substance use implementing TIC | (N = 168) | Pre-post survey | The impact of implementing TIC on the satisfaction of agency staff | Business Insight survey from Workplace Dynamics. Two trauma measures (not named) | Following the implementation of TIC, agency staff reported higher scores on all but one of the six satisfaction survey factors. TIC implementation is associated with increased staff satisfaction, and may positively influence organizational characteristics of significance to social service agencies. |

| Damien et al. (2017) [63] | USA | Journal article | Citywide implementation Government workers and nonprofit professionals | (N = 90) | Mixed methods | The impact of TIC training on later implementation | Safety Attitudes Questionnaire (SAQ); Professional Quality of Life (ProQoL) | Use of a mixed-methods approach provided a nuanced understanding of the impact of TIC training and suggested potential benefits of the training on organizational and provider-level factors associated with implementation of trauma-informed policies and practices |

| Kessler (2016) [64] | USA | Journal article | Employees working in disability service | (N = 20) | Qualitative interviews | This study explores staff understandings and perceptions within an innovative trauma-informed day program for individuals with Intellectual/developmental disabilities | N/A | Reasonable understandings of trauma and TIC, highlighting factors critical to the five principles of TIC. Differences were associated with duration of employment and the presence of specialized training. Challenges with TIC emerged at different system levels: individuals, staff, management and interorganizational. |

| Kirst et al. (2016) [65] | Canada | Journal article | Substance use and mental health facilitators and barriers to implementing trauma informed practices | (N = 19) | Qualitative interviews | To explore facilitators and barriers in implementing trauma-informed practices | N/A | Key facilitators included: organizational support, community partnerships, staff awareness of trauma, a safe environment, peer support, the quality of consumer-provider relationships, consumer, and provider readiness to change, and staff supports. Challenges included: provider reluctance to address trauma, lack of accessible services, limited funding for programs/services, and staff burnout |

| Study | Measure/s | Reliability | Validity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shier & Turpin (2022) [44] | Global Appraisal of Individual Needs Short Screener (GAINs-SS) | Cronbach’s a measure, the reliability of the total GAINs-SS at intake was 0.83 and 0.87 at program completion. | The short scale maintains good sensitivity and specificity for predicting diagnostic impressions |

| Intrapersonal Social Outcomes Development Scale. | Cronbach’s a measure for each measure ranged from 0.91 to 0.94, | Fit indices as shown in support the adoption of all five factors, which are shown to have overall strong construct validity for sample sizes under 500 | |

| The Trauma-Informed Organizational Environment Scale | Cronbach’s ranged between 0.84 and 0.89 for each of the factors, with the total measure at 0.87, | Fit indices from this analysis, indicated strong construct validity for every individual factor, as well as the higher order factor | |

| Piper et al. (2021) [47] | Survey adapted from Trauma-informed Organizational Toolkit | N/A | N/A |

| Robey et al. (2021) [48] | Adapted from The Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) | Internal consistency reliabilitywas acceptable to good staff 0.87 system 0.74 | TIC measure was positively related to staff-reported system support for TIC with a medium-sized effect, supporting its construct validity |

| Yoon (2021) [49] | Creating Cultures of Trauma-Informed Care Program Fidelity Scale Version 1.3 (CCTIC) | N/A | Not formally validated |

| Ontario Perception of Care –Mental Health and Addictions OPOC-MHA | Cronbach’s alpha > 0.80. | Construct validity exploratory factor analysis showed two factor structure | |

| Survey of Perceived Organizational Support Scale (SPOS) | Cronbach’s alpha 0.93 | Principle components factor analysis showed strong factor loading on the main factor, which was perceived support factor. | |

| Hales et al. (2019) [52] | Trauma-Informed Climate Scale (TICS) | Cronbach 0.91 | Confirmatory factor analyses supporting the scale’s construct validity |

| Trauma-Informed Organizational Self-Assessment. | Cronbach’s for the total scale was 0.99 | N/A | |

| Staff satisfaction was assessed using a 24-item instrument created internally. | Cronbach’s for the total scale was 0.94 | N/A | |

| Client satisfaction was assessed using a dichotomous (yes or no) 42-item instrument created by the agency | N/A | N/A | |

| Matlin et al. (2019) [54] | Trauma Training Survey | Cronbach 0.74 | N/A |

| Attitudes Related to Trauma-Informed Care | Cronbach 0.80 | N/A | |

| Trauma System Readiness Tool | Cronbach 0.95 | N/A | |

| Levels of Collaboration Scale | N/A | N/A | |

| Sundborg (2019) [55] | Affective Commitment Subscale Measure created for this study. | Cronbach 0.94 | N/A |

| The Beliefs about Trauma Scale was created for the current study. | Cronbach 0.81 | N/A | |

| Readiness for Organizational Change Scale (ROC); | Cronbach 0.85 | N/A | |

| Organizational Change Recipients’ Beliefs Scale (OCRBS) | Cronbach 0.84 | N/A | |

| Unick et al. (2019) [56] | Level of organizational trauma-informed care was measured using the TICOMETER | Cronbach 0.96 | High face and construct validity |

| Kessler & Isham (2017) [61] | Trauma Informed Care Measure | Initial psychometric properties for the full instrument are unavailable, subscales have alpha coefficients ranging from 0.721 to 0.849 | N/A |

| Hales et al. (2017) [62] | Business Insight survey from Workplace Dynamics. | N/A | N/A |

| Damien et al. (2017) [63] | Safety Attitudes Questionnaire (SAQ) | Cronbach 0.77 | N/A |

| Professional Quality of Life (ProQoL). | Cronbach 0.88 | N/A |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mahon, D. Implementing Trauma Informed Care in Human Services: An Ecological Scoping Review. Behav. Sci. 2022, 12, 431. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12110431

Mahon D. Implementing Trauma Informed Care in Human Services: An Ecological Scoping Review. Behavioral Sciences. 2022; 12(11):431. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12110431

Chicago/Turabian StyleMahon, Daryl. 2022. "Implementing Trauma Informed Care in Human Services: An Ecological Scoping Review" Behavioral Sciences 12, no. 11: 431. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12110431

APA StyleMahon, D. (2022). Implementing Trauma Informed Care in Human Services: An Ecological Scoping Review. Behavioral Sciences, 12(11), 431. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12110431