Nutrition, Sleep, and Exercise as Healthy Behaviors in Schizotypy: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

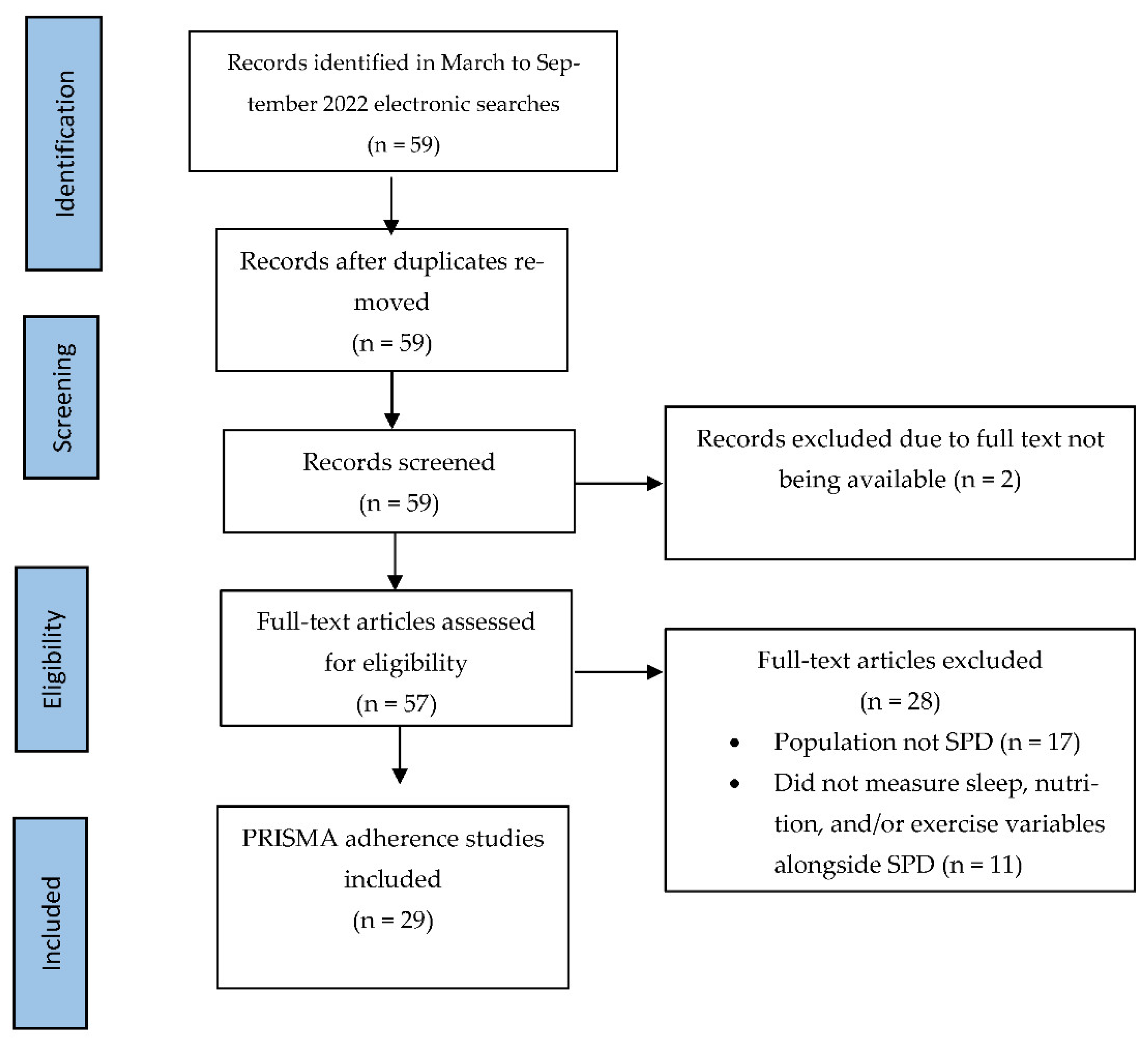

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Nutrition & SPD

3.2. Exercise & SPD

3.3. Sleep & SPD

3.4. Sleep, Exercise, & SPD

3.5. Nutrition, Exercise, Sleep & SPD

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jablensky, A. Epidemiology of schizophrenia: The global burden of disease and disability. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2000, 250, 274–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, M.K.; Lim, C.C.W.; Saha, S.; Plana-Ripoll, O.; Cannon, D.; Presley, F.; Weye, N.; Momen, N.C.; Whiteford, H.A.; Iburg, K.M.; et al. The cost of mental disorders: A systematic review. Epidemiol. Psychiatry Sci. 2020, 29, e161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.X.; Lam, S.P.; Zhang, J.; Yu, M.W.; Chan, J.W.; Chan, C.S.; Espie, C.A.; Freeman, D.; Mason, O.; Wing, Y.K. Sleep disturbances and suicide risk in an 8-year longitudinal study of schizophrenia-spectrum disorders. Sleep 2016, 39, 1275–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vancampfort, D.; Firth, J.; Schuch, F.B.; Rosenbaum, S.; Mugisha, J.; Hallgren, M.; Probst, M.; Ward, P.B.; Gaughran, F.; De Hert, M.; et al. Sedentary behavior and physical activity levels in people with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder: A global systematic review and meta-analysis. World J. Psychiatry 2017, 16, 308–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, K.K.; Raine, A. Schizotypal Personality Disorder. In The Wiley Encyclopedia of Personality and Individual Differences: Clinical, Applied, and Cross-Cultural Research; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 115–120. [Google Scholar]

- Rosell, D.R.; Futterman, S.E.; McMaster, A.; Siever, L.J. Schizotypal personality disorder: A current review. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2014, 16, 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Debbané, M.; Eliez, S.; Badoud, D.; Conus, P.; Flückiger, R.; Schultze-Lutter, F. Developing psychosis and its risk states through the lens of schizotypy. Schizophr. Bull. 2015, 41 (Suppl. 2), S396–S407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenzenweger, M.F. Psychometric high-risk paradigm, perceptual aberrations, and schizotypy: An update. Schizophr. Bull. 1994, 20, 121–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. Anxiety Disorders. In Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Zonneveld, S.M.; Haarman, B.C.; van den Oever, E.J.; Nuninga, J.O.; Sommer, I.E. Unhealthy diet in schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Curr. Op. Psychiatry 2022, 35, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carruthers, S.P.; Brunetti, G.; Rossell, S.L. Sleep disturbances and cognitive impairment in schizophrenia spectrum disorders: A systematic review and narrative synthesis. Sleep Med. 2021, 84, 8–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firth, J.; Stubbs, B.; Vancampfort, D.; Schuch, F.B.; Rosenbaum, S.; Ward, P.B.; Yung, A.R. The validity and value of self-reported physical activity and accelerometry in people with schizophrenia: A population-scale study of the UK Biobank. Schizophr. Bull. 2018, 44, 1293–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, K.K.; Raine, A. Developmental aspects of schizotypy and suspiciousness: A review. Curr. Behav. Neurosci. Rep. 2018, 5, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raine, A. Schizotypal personality: Neurodevelopmental and psychosocial trajectories. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2006, 27, 291–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Method. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aucoin, M.; LaChance, L.; Cooley, K.; Kidd, S. Diet and Psychosis: A Scoping Review. Neuropsychobiology 2020, 79, 20–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amminger, G.P.; Schäfer, M.R.; Papageorgiou, K.; Klier, C.M.; Cotton, S.M.; Harrigan, S.M.; Mackinnon, A.; McGorry, P.D.; Berger, G.E. Long-chain ω-3 fatty acids for indicated prevention of psychotic disorders: A randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Archiv. Gen. Psychiatry 2010, 67, 146–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGorry, P.D.; Nelson, B.; Markulev, C.; Yuen, H.P.; Schäfer, M.R.; Mossaheb, N.; Schlögelhofer, M.; Smesny, S.; Hickie, I.; Berger, G.E.; et al. Effect of ω-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids in Young People at Ultrahigh Risk for Psychotic Disorders: The Neurapro Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Psychiatry 2017, 74, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raine, A.; Mellingen, K.; Liu, J.; Venables, P.; Mednick, S.A. Effects of environmental enrichment at ages 3–5 years on schizotypal personality and antisocial behavior at ages 17 and 23 years. Am. J. Psychiatry 2003, 160, 1627–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venables, P.H.; Raine, A. Poor nutrition at age 3 and schizotypal personality at age 23: The mediating role of age 11 cognitive functioning. Am. J. Psychiatry 2012, 169, 822–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hock, R.S.; Bryce, C.P.; Fischer, L.; First, M.B.; Fitzmaurice, G.M.; Costa, P.T.; Galler, J.R. Childhood malnutrition and maltreatment are linked with personality disorder symptoms in adulthood: Results from a Barbados lifespan cohort. Psychiatry Res. 2018, 269, 301–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, A.; Macdonald, A.; Walker, E. The treatment of adolescents with schizotypal personality disorder and related conditions: A practice-oriented review of the literature. Clin. Psychol. 2013, 20, 408. [Google Scholar]

- Fusar-Poli, P.; De Marco, L.; Cavallin, F.; Bertorello, A.; Nicolasi, M.; Politi, P. Lifestyles and cardiovascular risk in individuals with functional psychoses. Perspect. Psychiatry Care 2009, 45, 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mittal, V.A.; Gupta, T.; Orr, J.M.; Pelletier-Baldelli, A.; Dean, D.J.; Lunsford-Avery, J.R.; Millman, Z.B. Physical activity level and medial temporal health in youth at ultra high-risk for psychosis. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2013, 122, 1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorczynski, P.; Faulkner, G. Exercise therapy for schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2010, 5, 1465–1858. [Google Scholar]

- Beebe, L.H.; Smith, K. Feasibility of the Walk, Address, Learn and Cue (WALC) intervention for schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Arch. Psychiatry Nurs. 2010, 24, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beebe, L.H.; Smith, K.; Burk, R.; McIntyre, K.; Dessieux, O.; Tavakoli, A.; Tennison, C.; Velligan, D. Effect of a motivational intervention on exercise behavior in persons with schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Community Ment. Health J. 2011, 47, 628–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Orleans-Pobee, M.; Browne, J.; Ludwig, K.; Merritt, C.; Battaglini, C.L.; Jarskog, L.F.; Sheeran, P.; Penn, D.L. Physical Activity Can Enhance Life (PACE-Life): Results from a 10-week walking intervention for individuals with schizophrenia spectrum disorders. J. Ment. Health 2021, 31, 357–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beebe, L.H.; Smith, K.D.; Roman, M.W.; Burk, R.C.; McIntyre, K.; Dessieux, O.L.; Tavakoli, A.; Tennison, C. A pilot study describing physical activity in persons with schizophrenia spectrum disorders (SSDS) after an exercise program. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2013, 34, 214–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, J.; Kyle, S.D.; Varese, F.; Jones, S.H.; Haddock, G. Are sleep disturbances causally linked to the presence and severity of psychotic-like, dissociative and hypomanic experiences in non-clinical populations? A systematic review. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2018, 89, 119–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koffel, E.; Watson, D. Unusual sleep experiences, dissociation, and schizotypy: Evidence for a common domain. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2009, 29, 548–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simor, P.; Báthori, N.; Nagy, T.; Polner, B. Poor sleep quality predicts psychotic-like symptoms: An experience sampling study in young adults with schizotypal traits. Acta Psychiatry Scand. 2019, 140, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ancoli-Israel, S. Sleep and its disorders in aging populations. Sleep Med. 2009, 10, S7–S11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claridge, G.; Clark, K.; Davis, C. Nightmares, dreams, and schizotypy. B. J. Clin. Psychol. 1997, 36, 377–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, D. Dissociations of the night: Individual differences in sleep-related experiences and their relation to dissociation and schizotypy. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2001, 110, 526–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, R. Nightmares and schizotypy. Psychiatry 1998, 61, 206–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, R.; Fireman, G. Nightmare prevalence, nightmare distress, and self-reported psychological disturbance. Sleep 2002, 25, 205–212. [Google Scholar]

- Levin, R.; Raulin, M.L. Preliminary evidence for the proposed relationship between frequent nightmares and schizotypal symptomatology. J. Personal. Dis. 1991, 5, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, H.M.; Zborowski, M.J. Schizophrenia-proneness, season of birth and sleep: Elevated schizotypy scores are associated with spring births and extremes of sleep. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2006, 41, 1185–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.; Zhang, X.; Zou, L. The mediating effect of alexithymia on the relationship between schizotypal traits and sleep problems among college students. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, J.; Koch, L.; Wilford, C.; Boubert, L. An investigation into personality, stress and sleep with reports of hallucinations in a normal population. Psychology 2011, 2, 371–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Knox, J.; Lynn, S.J. Sleep experiences, dissociation, imaginal experiences, and schizotypy: The role of context. Conscious. Cogn. 2014, 23, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Báthori, N.; Polner, B.; Simor, P. Schizotypy unfolding into the night? Schizotypal traits and daytime psychotic-like experiences predict negative and salient dreams. Schizophr. Res. 2022, 246, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- O’Kane, T.W.; Sledjeski, E.M.; Dinzeo, T.J. The examination of sleep hygiene, quality of life, and schizotypy in young adults. J. Psychiatry Res. 2022, 150, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faiola, E.; Meyhöfer, I.; Steffens, M.; Kasparbauer, A.M.; Kumari, V.; Ettinger, U. Combining trait and state model systems of psychosis: The effect of sleep deprivation on cognitive functions in schizotypal individuals. Psychiatry Res. 2018, 270, 639–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lustenberger, C.; O’Gorman, R.L.; Pugin, F.; Tüshaus, L.; Wehrle, F.; Achermann, P.; Huber, R. Sleep spindles are related to schizotypal personality traits and thalamic glutamine/glutamate in healthy subjects. Schizophr. Bull. 2015, 41, 522–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuula, L.; Merikanto, I.; Makkonen, T.; Halonen, R.; Lahti-Pulkkinen, M.; Lahti, J.; Pesonen, A.K. Schizotypal traits are associated with sleep spindles and rapid eye movement in adolescence. J. Sleep Res. 2019, 28, e12692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrarelli, F.; Huber, R.; Peterson, M.J.; Massimini, M.; Murphy, M.; Riedner, B.A.; Watson, A.; Bria, P.; Tononi, G. Reduced sleep spindle activity in schizophrenia patients. Am. J. Psychiatry 2007, 164, 483–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrarelli, F. Sleep disturbances in schizophrenia and psychosis. Schizophr. Res. 2020, 221, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wamsley, E.J.; Tucker, M.A.; Shinn, A.K.; Ono, K.E.; McKinley, S.K.; Ely, A.V.; Goff, D.C.; Stickgold, R.; Manoach, D.S. Reduced sleep spindles and spindle coherence in schizophrenia: Mechanisms of impaired memory consolidation? Biol. Psychiatry 2012, 71, 154–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, K.K.; Raine, A. COVID-19: Global social trust and mental health study. OSF 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, K.K.; Wang, Y.; Esposito, G.; Raine, A. A three-wave network analysis of COVID-19′s impact on schizotypal traits, paranoia and mental health through loneliness. UCL Open 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daimer, S.; Mihatsch, L.; Ronan, L.; Murray, G.K.; Knolle, F. Are we back to normal yet? The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health with a specific focus on schizotypal traits in the general population of Germany and the UK, comparing responses from April/May vs. September/October. medRxiv 2021. medRxiv:2021.02. [Google Scholar]

- Dinzeo, T.J.; Thayasivam, U. Schizotypy, Lifestyle Behaviors, and Health Indicators in a Young Adult Sample. Behav. Sci. 2021, 11, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennacchi, A.C. Factors Influencing Health Behaviors in those at Risk for Developing Schizophrenia; Rowan University: Glassboro, NJ, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Golan, M.; Hagay, N.; Tamir, S. The effect of “In Favor of Myself”: Preventive program to enhance positive self and body image among adolescents. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e78223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggar, C.; Thomas, T.; Gordon, C.; Bloomfield, J.; Baker, J. Social prescribing for individuals living with mental illness in an Australian community setting: A pilot study. Community Men. Health J. 2021, 57, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raine, A.; Reynolds, C.; Lencz, T.; Scerbo, A.; Triphon, N.; Kim, D. Cognitive–perceptual, interpersonal and disorganized features of schizotypal personality. Schizophr. Bull. 1994, 20, 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author(s) | Year | Exposure Variable | Origin (Where the Study Was Published or Conducted) | Aims/Purpose | Study Population | Sample Size | Methods | Outcomes Measures | Key Findings in Relation to Review Question |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amminger, Schäfer, Papageorgiou., et al. | 2010 | Nutrition | Vienna, Austria | Efficacy of omega-3 supplement in reducing/slowing the conversion to psychosis in ultra-high-risk patients. | Adolescent ultra-high-risk patients diagnosed with schizophrenia-spectrum disorder (SSD) and schizotypy aged 13 to 25 years old. | N = 81 Treatment n = 40 vs. placebo n = 40 (F = 53, M = 27) | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial investigating the role of omega-3 PUFAs supplements on slowing the progression to first-episode psychotic disorders and symptom reduction in patients. A total of 81 patients deemed as ultra-high risk with a diagnosis of schizophrenia-spectrum disorders and schizotypal personality disorder were randomly assigned to either the treatment condition (n = 40), where they received a daily dose of approximately 1.2-g omega-3 PUFAs or the placebo group (n = 40) who received a daily coconut oil capsule containing vitamin E and 1% fish oil to match the appearance and flavor of the treatment capsule. | Conversion to psychosis (PANSS), global functioning | In total, 76 participants completed the trial (93.8%). Compared with the placebo group, treatment group patients were significantly less likely to convert to psychosis at 12-month follow-up, 4.9% vs. 27.5%. Patients who received omega-3 PUFAs reported significantly better global functioning compared to the control group and reductions across symptoms with moderate (negative symptoms) and moderate to large effects (positive, general, total symptoms). The reduction in prodromal symptoms and functioning in the treatment group was sustained even after the intervention stopped. These findings suggest a positive potential behavioral response to omega-3 supplementation in intervening and slowing down symptom progression in young people at ultra-high risk for developing schizophrenia. |

| Barnes, Koch, Wilford and Boubert | 2011 | Sleep | UK | An investigation into personality, stress, and sleep with reports of hallucinations in a normal population | Oxford Brookes university students. | N = 117 (F = 75, M= 42) | Self-report survey data; cross-sectional | sleep (Pittsburgh), schizotypy (PRE-MAG) | Cognitive Disorganization (r = 0.365), Introvertive anhedonia (r = 0.305), and Unusual Experiences (r = 0.239). |

| Báthori, Polner and Simor | 2022 | Sleep | Hungary | A three-week long study to examine the bidirectional, temporal links between dream emotions and daytime PLEs, taking into consideration schizotypal personality traits | Non-clinical individuals with high dream recall | N = 55 (F = 42, M = 13) | Self-report survey data, cross-sectional | Schizotypy (O-LIFE) Sleep (the “Morning Questionnaire”, an 8-point single item survey where participants rated the quality of their sleep) | General Disorganized schizotypy predicted negatively valanced dream emotions. Dream emotions were both predicted by dispositional schizotypal traits and by psychotic-like experiences as measured the night before sleep. |

| Beebe & Smith | 2010 | Exercise | South-eastern USA | Assessing the feasibility of the Walk, Address, Learn, and Cue (WALC) intervention for schizophrenia spectrum disorders | People with SSDs receiving care at an outpatient treatment facility | N = 17 (F = 7, M = 10; Mage = 43.2 years, range = 24–54 years; ) | Randomly assigned outpatients with SSDs who are receiving care at a treatment facility to receive weekly hour-long motivational intervention group session (N = 17). Most of the participants were male Caucasians with schizoaffective disorder and on antipsychotic medication. | Demographic data were collected at study entry and included: age, race, gender, living arrangement, chart diagnosis, and self-reported educational level. Attendance at WALC-S groups was defined as the percentage of sessions attended out of the total sessions offered. Reasons for nonattendance were obtained during follow-up telephone calls after each WALC-S group. | Compared with the control group, individuals in the experimental group who received the motivational intervention session prior to the walking intervention attended more walking groups, stayed with the group for longer, and reported on average more minutes walking each month, demonstrating sustained engagement with the activity. However, no measures of symptoms of SSD were assessed and so it is unknown whether increased exercise reduces symptoms. |

| Beebe, Smith, Burk, et al. | 2011 | Exercise | Southeastern USA | Aimed to look at the effect of a motivational intervention on exercise behavior in persons with schizophrenia spectrum disorders. | outpatients with SSDs | N = 97 (treatment = 48 vs. controls = 49; average age = 46.9 years (SD = 2.0) (F = 46, M = 51) | Data collection at 2 years post waking intervention program. | Exercise (Walking group attendance, persistence, compliance) | Treatment group reported higher levels of exercise attendance, persistence and compliance compared to controls. WALC-S recipients attended more walking groups, for more weeks and walked more minutes than those receiving TAC. Percent of WALC-S or TAC groups attended was significantly correlated with overall attendance (r = 0.38, p = 0.001) and persistence (r = −0.29, p = 0.01), as well as number of minutes walked. This study is among the first to examine interventions designed to enhance exercise motivation in SSDs. |

| Beebe et al. | 2013 | Exercise | Southeastern USA | To examine the sustained impact of an exercise intervention on individuals with SSD at 14 and 34 months post-RCT program | Followed-up individuals with SSDs who had taken part in an RCT exercise intervention to see how they fair at 14–34 months | N = 22 (23–71 years-old; 11 = exp, 11 = control) (F = 11, M = 11) | Measured participants’ step count and distance covered using a pedometer | Exercise (steps and distance using pedometers) | Found that the experimental group participants walked more steps and cover more distance on average than control participants on 6 of the 7 days. Physical activity level of persons with SSDs after exercise intervention. <5000 steps daily = sedentary; 7000–13,000 steps/daily = healthy. |

| Claridge, Clark, and Davis | 1998 | Sleep | UK | Nightmares, dreams, schizotypy | Community-residing 14–55-year-olds | (N = 204) convenience sample (M = 87, F = 117) | Self-report survey data, cross-sectional | Schizotypy (STA), age, sleep (Belicki’s Nightmare Distress scale) | Found that higher levels of nightmare distress are associated with more schizotypy, but interestingly also more vivid and enjoyable dreaming (attributed to greater imagination abilities in magical thinking). |

| Daimer, Mihatsch, Ronan, et al. | 2021 | Sleep and Exercise | Germany & UK | Investigated the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health with a specific focus on schizotypal traits in the general population of Germany and the UK in April/May vs. September/October 2020 | Independent samples in the UK and Germany during May 2020 and October 2020 | UK (N = 239, N = 126) Germany (N1 = 543, N2 = 401) Gender distribution: first survey (F = 72%, M = 25%, undefined: 3%), second survey (F: 69%, M: 25%, undefined: 6%) | Two independent samples from the UK and Germany self-reporting on a survey at two time-points | Schizotypy (SPQ), exercise (days with physical exercise per week) and sleep (hours per night) quality measured by hours | Found that higher schizotypy scores, especially F2, in October compared with May 2020. Moderate physical exercise was associated with decreases in SPQ scores. Those who exercised 5 or more times a week reported concurrently lower levels of schizotypy for May and October 2020. Those who slept 6–8 h and 8 h+ reported lower levels of schizotypy compared with those with under 6 h of sleep. |

| Dinzeo and Thayasivam | 2021 | Sleep, Nutrition, and Exercise | USA | Investigated the relationship between schizotypy, lifestyle behaviors, and health in a young adult sample | University students | N = 530 (F = 48.6%, M = 51.4%) | Self-report survey data, cross-sectional | Schizotypy (SPQ-B), exercise (LHQ-B), sleep quality (PSQI) | Increased schizotypy symptoms were associated with poorer sleep quality across positive, negative, and disorganized domains. Individuals scoring high on all three schizotypy domains reported significant more severe somatic symptoms, poorer psychological health (e.g., reduced engagement with health behaviors), and more sleep difficulties compared to individuals self-reporting as being low across schizotypy domains. The schizotypy group did not differ on the nutrition indicator, which measures engagement with healthy food intake levels. Regarding physical exercise, individuals reporting high and intermediate levels of interpersonal deficits (negative) schizotypy reported significant low levels of exercise, while individuals reporting high on disorganized features were only trending, and no differences were found in exercise levels for those with cognitive-perceptual deficits (positive) of schizotypy. |

| Faiola et al. | 2018 | Sleep | Germany | Replicating previous findings of cognitive deficits in high (as compared to low) schizotypy and after sleep deprivation (as compared to normal sleep), and the group by sleep interactions | Healthy subjects with high or low levels of positive schizotypy | N = 36 (out of 5006 completed survey) (high schizotypy (≥1.25 SD) = 17 vs. low schizotypy(≤0.5 SD) = 19) (F = 24, M = 12) | Sleep report survey and sleep deprivation intervention | Schizotypy (O-LIFE) Sleep (sleep deprivation intervention) | Sleep deprivation impaired performance in the go/no-go and n-back tasks relative to the normal sleep control condition, suggesting that sleep deprivation had implications on inhibitory control and potentially, overall attention to task rather than working memory deficits. However, no differences were found between groups or interaction with sleep conditions, suggesting no cognitive impairments across schizotypy groups. This is perhaps due to the small sample size and strength of the sleep deprivation condition (more than 24 h deprivation needed). |

| Firth et al. | 2018 | Exercise | UK | Using large-scale population-based UK Biobank study data, to examine the difference in objective and subject measures of physical activity. | Individuals with schizophrenia and SSDs | N = 1078 (F = 45%, M = 55%) | Self-report survey data, accelerometer data, cross-sectional | Physical activity (accelerometer) (IPAQ), Schizophrenia-spectrum disorder status | SSD individuals had significantly lower accelerometer ratings (e.g., physical activity as represented by the average vector magnitude, a combination of time and intensity of movement in a week) than controls (n = 450,549), demonstrating high levels of sedentary behavior, which is often not reflected in self-reported measures of physical activity. |

| Hock et al. | 2018 | Nutrition | Barbados | To examine the unique and combined associations of exposures to early malnutrition and childhood maltreatment with PD scores in middle adulthood | Children born between 1967 and 1972 who had experienced moderate to severe protein-energy malnutrition in their first year of life | N = 139 (malnutrition = 77 vs. control = 62; Mage = 43.8, SD = 2.3 years) (F = 66, M = 73) | Self-reported survey, structured interviews. Participants were split into a previously malnourished group and a control group. They compared mean scores of personality pathology by malnutrition history group. They also ran linear regression analyses with malnutrition histories as independent predictor variables and adult personality pathology as dependent variables. | Assessments at 40–45 years: Early malnutrition (protein-energy marasmus in the first year of life) Personality disorder (NEO FFM PD, SCID-II-PQ) | Malnutrition positively correlated with SPD but not significant after adjusting for childhood maltreatment and standard of living. |

| Knox & Lynn | 2014 | Sleep | New York, USA | To evaluate the contextual independence and the generalizability of the relation between sleep-related experiences and a variety of measures (including schizotypy) found to correlate with such experiences when assessed in the same context | Undergraduate students at the State University of New York. | N = 173 86 participants in the out-of-context condition vs. 87 in the in-context condition (F = 106, M = 67; Median age = 18 years; range = 17 to 24 years) | Self-reported surveys. Participants completed the measures over two separate 1-h experimental sessions—a “personality” session and a “sleep” session. | Sleep (ISES, PSQI) Schizotypy (PER-MAG, REF, SAS) | Sleep experiences were associated with measures of dissociation, absorption, and schizotypy. Of the schizotypy measures, magical ideation is the strongest correlate of unusual sleep experiences. Observed relations between sleep experiences and measures of schizotypy are unaffected by variations in the experimental context and appear to be generalizable in this regard. |

| Koffel and Watson | 2009 | Sleep | USA | Extensive review on the relationship between unusual sleep experiences, dissociation, and schizotypy in both clinical and non-clinical samples | studies | N/A | Review paper | Sleep (nightmares, vivid dreaming, narcolepsy symptoms, and complex night time behaviors), dissociation, schizotypy (PANAS) | Found that unusual sleep experiences (e.g., nightmares, vivid dreams, narcolepsy symptoms, complex behaviors at night) are associated with symptoms of dissociation/schizotypy in both clinical and non-clinical samples. Evidence that unusual sleep experiences, dissociation, and schizotypy are more strongly related to each other than to other measures of daytime symptoms (e.g., negative affectivity/neuroticism, depression, anxiety, substance use) and sleep complaints (e.g., insomnia and lassitude). |

| Kuula, Merikanto, Makkonen, et al. | 2019 | Sleep | Helsinki, Finland | Investigated schizotypal traits, sleep spindles, and rapid eye movement in adolescence | Adolescents (urban community-based cohort composed of 1049 healthy singletons born between March and November 1998 in Helsinki, Finland) | N = 176 (Mean = 12.3 years) (F = 61%, M = 39%) | Behavioral and self-reported survey; cross-sectional | Sleep spindle morphology (ambulatory overnight polysomnography), REM sleep (EEG), schizotypy (SPA) | Found sleep spindle morphology to be associated with a higher proportion of rapid eye movement (REM) sleep—defined as when an individual is having vivid dreams—and high levels of schizotypy. |

| Levin | 1998 | Sleep | USA | Iinvestigated the relationship between nightmares and schizotypy | university female students; frequent nightmare group with at least 1 weekly nightmare | N = 60 (30 recurring nightmare group, 30 control group) | Self-report survey data; cross-sectional | Schizotypy (Chapman scale, SSP), depression (BDI), anxiety (STAI), nightmare (1 page description) | Found that those with DSM III SPD diagnosis reporting 1+ nightmares/week reported significantly more schizotypal traits, specifically magical ideation, compared to those who report no nightmares in the same duration. |

| Levin & Raulin | 1991 | Sleep | USA | Investigated the relationship between frequent nightmares and schizotypal symptomatology | University students | N = 669 (F = 446, M = 223) | Self-report survey data; cross-sectional | Schizotypy (four scales measuring perceptual aberration, intense ambivalence, and somatic symptoms. The origin of these scales can be found on p. 9) Sleep (nightmare frequency checklist), sex | Found a positive relationship between nightmare frequency and 3 (perceptual aberration, intense ambivalence, and somatic symptoms) of 4 schizotypy measures. Observed relationships stronger for females than for males. There was a negative relationship between physical anhedonia and nightmare frequency. |

| Levin & Fireman | 2002 | Sleep | USA | Nightmare prevalence, nightmare distress, and self-reported psychological disturbance | University students | N = 116 (mean age = 20 years) (F = 85, M = 31) | Self-report survey data; cross-sectional | Sleep (frequency and distress—21-day dream logs with Likert-rating scales), schizotypy (SPQ) | Found that those who reported 3+ nightmares/week reported significant more schizotypy traits than those who reported 2 nightmares/week. It is nightmare distress not frequency that is associated with psychological disturbances like anxiety/depression/dissociation (r = 0.31–0.55). Nightmare distress was also associated with prevalence of nightmare reported in diary logs. Limitation of study does not include childhood trauma. |

| Lustenberger, O’Gorman, Pugin, et al. | 2015 | Sleep | Zurich, Switzerland | Sleep spindles are related to schizotypal personality traits and thalamic glutamine/glutamate in healthy subjects | Zurich University healthy men | N = 20 (age = 23.3 ± 2.1 years) | Self-report survey and 2 all-night sleep electroencephalography recordings (128 electrodes). | Sleep spindle densities (EEG), schizotypy (SPQ) | Found a relationship between sleep spindles density and scores on the Schizotypal Personality Questionnaire (SPQ) in healthy university men in Zurich (N = 20) (r = −0.64, p < 0.01), but not thalamic glutamate Glx levels. |

| Ma, Zhang, & Zou | 2020 | Sleep | Guangzhou, China | The mediating effect of alexithymia on the relationship between schizotypal traits and sleep problems among college students | First year university medical students | N = 2626 (18–25 years old) (F = 1601, M = 1025) | Self-report survey data; convenience sample; cross-sectional | Sleep (ISI), schizotypy (SPQ) | Found a link between poor sleep and higher general schizotypy scores range from 0.31 to 0.45 based on convenient samples, large-scale cross-sectional self-report survey data. |

| McGorry, Nelson, Markulev, et al. | 2017 | Nutrition | Australia, Asia, Europe | Efficacy of omega-3 supplement in reducing/slowing the conversion to psychosis in ultra-high-risk adolescents | Patients with ultra-high risk for psychosis either received 1.4 g of omega-3 PUFAs or a placebo (paraffin oil), in addition to 20 or fewer sessions of high-quality psychosocial intervention (cognitive behavioral case management and antidepressants) over a 6-month study period. | N = 304 (age = 13–40 years) (F = 165, M = 139) 153 ω-3 PUFAs vs. 151 placebos | Large double-blind placebo-controlled randomized clinical trial | Conversion to psychosis (the Comprehensive Assessment of theAt-Risk Mental State), functioning (Global Functioning: Social and Rolescales) | Conversion to psychosis status at 6 months for the intervention and control group was 6.7% and 5.1%, and at 12 months, 11.5% and 11.2%, respectively, suggesting no significant treatment effect of omega-3 PUFAs in reducing transition to psychosis. However, symptom and functional improvements were observed more broadly for both groups. |

| O’Kane, Sledjeski and Dinzeo | 2022 | Sleep | Northeastern USA | To investigate how sleep hygiene is related to three frequently examined sub-domains of schizotypy (i.e., positive, negative, disoganized) and QOL | Undergraduate students from a mid-sized university | N = 385 (F = 242, M = 143; Mage = 20.83, SD = 3.61 years)) | Self-report surveys; cross-sectional | Schizotypy (SPQ-BR), sleep hygiene (SHI) | Sleep hygiene (measured through patterns of pre-sleep behaviors) may be a relevant risk variable in the development of schizophrenia-spectrum symptoms. Sleep experiences associated with measures of schizotypy. Specifically, higher levels of schizotypy were associated with emotional rumination prior to sleep, while increased negative schizotypy was associated with poorer quality of life. Sex differences observed across schizotypy subscale except for disorganized features. |

| Orleans-Pobee, Browne, Ludwig et al. | 2021 | Exercise | Southeastern USA | To examine the impact of Physical Activity Can Enhance Life (PACE-Life), a novel walking intervention, on physical activity, and on secondary outcomes of cardiorespiratory fitness (CRF), physical health, autonomous motivation, social support, and quality of life | Individuals with SSDs were enrolled in a 10-week open trial |

N = 16 (F = 2, M = 14) | Within-group effect sizes were calculated to represent changes from baseline to post-test and 1-month follow-up | Physical health, walking groups, home-based walks, Fitbit use, and goal setting and if-then plans (Fitbit PA trackers, IPAQ, BREQ-2, 6MWT) | Participants increased self-reported weekly walking minutes and decreased daily hours spent sitting; however, Fitbit-recorded exercise behavior changed only minimally. Cardiovascular fitness only improved marginally. |

| Pennacchi | 2013 | Nutrition and exercise | USA | Factors influencing health behaviors in those at risk for developing schizophrenia. | University students | N = 115 (F = 52%, M = 47%, other: 0.9%) | Self-report survey data, food diaries | Schizotypy (SPQ-B), nutrition (nutrition calculator), physical activity (GPAQ, LHQ-B), self-perception of fitness level relative to peers, eating habits (24-h diet recall log, interviews) | Only the unusual perceptual deficits subscale within the positive symptoms of schizotypy was predictive of healthier behaviors on health and exercise, and overall higher negative symptoms of schizotypy were associated with eating less nutritious foods (e.g., salad) and likelihood of eating out, self-perceived poorer fitness levels relative to peers, and with being less likely to engage in exercising. No relationship was found between negative schizotypy and eating habits. |

| Raine, Mellingen, Liu, Venables, and Mednick | 2003 | Nutrition | Mauritius, Africa | To examine the effects of environmental enrichment at ages 3–5 years on schizotypal personality and antisocial behavior at ages 17 and 23 years | 3–5-year-olds in the treatment | N = 455 Children in treatment (N = 100) vs. control group (N = 355) (F = 48.6%, M = 51.4%) | Large double-blind placebo-controlled randomized trial | Schizotypy (SPQ), full behavioral outcome data were available at age 17 (n = 83) and 23 years (n = 73) that allowed for comparison with the control group (n = 355) Nutrition (7 indicators of malnutrition: reduced height for age, reduced weight for height, hemoglobin levels, angular stomatitis, hair dyspigmentation, thin hair, and hair that is easy to pull out) | This 2-year intervention found that compared to children in the control condition, no main effect for schizotypy and intervention groups at age 23—the effects were an interaction between enrichment and malnourished status at age 3. Main effects for schizotypy and intervention was found at age 17 years. These findings were especially stark for children who were deemed as malnourished at age 3 years, suggesting that an enriched, stimulating environment is beneficial for psychological and behavioral outcomes even 14 and 20 years later in life. |

| Reid and Zborowski | 2006 | Sleep | New York, USA | Investigated the birth timing effects during the year and how that is associated with levels of schizotypy and the amount of sleep. | Western New York University students | N = 452 (out of 530) (F = 75.4%, M = 24.6%; Mage = 21.31, SD = 5.05 years) | Self-report surveys; cross-sectional | Birth date, schizotypy (PER-MAG), sleep | Individuals born in Winter rather than in Spring have higher schizotypy scores. Those sleeping <6 h or 8 h+ scored in the top 25% on the PER-MAG scale compared to those who slept 6,7,8 h. Higher schizotypy scores reported by those born in the Winter/Spring (21 Dec–20 June) > Summer/Fall (21 June–20 Dec). |

| Simor, Báthori, Nagy, and Polner | 2019 | Sleep | Hungarian | Poor sleep quality predicts psychotic-like symptoms: an experience sampling study in young adults with schizotypal traits | Hungarian university students with schizotypy | N = 73 (18–25 years old) (F = 61, M = 12) | Assessed subjective sleep quality and how it predicts fluctuations in PLEs the next few days and sleep quality. | Sleep quality (GSQS-H), psychotic-like experiences, schizotypy (s-OLIFE) | Found that poor sleep quality predicts psychotic-like experiences in young adults with schizotypy (n = 73 Hungarian university students 18–25 year-olds with moderate to high levels of positive schizotypy). Participants rated the sleep every morning, PLEs and affective stated during the day for 3 weeks. Participants with score > 4 on the Unusual Experience subscale (s-OLIFE). Found that subjective sleep quality predicts day-to-day fluctuations in PLEs in the next few days, poorer sleep quality and shorter sleep associated with increased PLEs the following day. Limitation no objective measure of sleep. |

| Watson | 2001 | Sleep | Iowa, USA | First, to create a simple, reliable measure tapping a broad range of sleep-related experiences. Second, to examine the nature of individual differences in sleep experiences. Third, to clarify the underlying structure of the broader domain by examining the nature of the relation between dissociation and schizotypy. | Two samples of students who were enrolled in an introductory psychology course at the University of Iowa | N = 482 Sample 1 (F = 285, M = 196, undefined = 1) N = 466 Sample 2 (F = 299, M = 166, undefined = 1) | Two large undergraduate samples self-reporting on a survey (Complete data on N1 = 471, N2 = 457) | Schizotypy (Perceptual Aberration scale, Magical Ideation scale, STQ Schizotypal Personality Scale) Sleep (ISES) | Moderate positive correlations between the Iowa Sleep Experience Survey (ISES) and self-report measures of dissociation and schizotypy—individuals who score high on the measures schizotypy also tend to score high on the ISES General Sleep Experiences Scale. |

| Wong, Wang, Esposito, & Raine | 2022 | Sleep | Worldwide | A three-wave network analysis of COVID-19’s impact on schizotypal traits, paranoia, and mental health through loneliness | General population adults aged 18–89 years-old primarily from the UK, US, Italy, and Greece across three time-points | Over 2300 participants (18–89 years) (F = 74.9%, M = 25.1%) | Self-report survey data | Sleep (Pittsburgh), schizotypy (SPQ-B) | Found that symptoms of schizotypy were more elevated at time 2 (October–January 2021) compared to times 1 and 3, and at every timepoint they were positively associated with poorer sleep, primarily through changes in the individual’s stress concerning the pandemic and depressive symptoms |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wong, K.K.-Y.; Raine, A. Nutrition, Sleep, and Exercise as Healthy Behaviors in Schizotypy: A Scoping Review. Behav. Sci. 2022, 12, 412. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12110412

Wong KK-Y, Raine A. Nutrition, Sleep, and Exercise as Healthy Behaviors in Schizotypy: A Scoping Review. Behavioral Sciences. 2022; 12(11):412. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12110412

Chicago/Turabian StyleWong, Keri Ka-Yee, and Adrian Raine. 2022. "Nutrition, Sleep, and Exercise as Healthy Behaviors in Schizotypy: A Scoping Review" Behavioral Sciences 12, no. 11: 412. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12110412

APA StyleWong, K. K.-Y., & Raine, A. (2022). Nutrition, Sleep, and Exercise as Healthy Behaviors in Schizotypy: A Scoping Review. Behavioral Sciences, 12(11), 412. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12110412