Abstract

Although associations between physical or sexual abuse and aggression have been mainly explored, relationships and pathways between childhood emotional maltreatment and aggression need further exploration, particularly in the Chinese cultural context. This study aimed to explore the associations between childhood emotional maltreatment and aggression and to examine the mediating effects of resilience and self-esteem on those associations. Data were obtained from a convenience sampling of 809 (aged 17–23) college students from three Chinese universities in December 2021, which was approved by the ethics committee of Beijing Normal University, China. All participants completed measures of childhood emotional maltreatment, aggression, resilience, and self-esteem. The results showed that childhood emotional maltreatment was positively associated with aggression (r = 0.41, p < 0.01), and it was negatively associated with resilience (r = −0.56, p < 0.01) and self-esteem (r = −0.10, p < 0.01). Regarding the mediation processes, resilience and self-esteem partially mediated the relationships between childhood emotional maltreatment and aggression. These findings underscore the importance of enhancing levels of resilience and self-esteem in interventions designed to reduce aggression of college students who were emotionally maltreated in childhood.

1. Introduction

Child maltreatment, defined as any recent act (or failure to act) which a child suffers from caregivers [1], has been confirmed to impair child development, which may contribute to it being an important worldwide public health issue [2]. Childhood emotional maltreatment (CEM), including emotional abuse and emotional neglect, reflects emotional interactions between a child and caregiver(s), and it may be the most common subtype of child maltreatment, due to its high prevalence (36%) [3].

Aggression, as a method of externalizing problems, may be an index for later maladaptation, which may be influenced by adverse childhood experiences, such as childhood maltreatment [4]. Some studies have explored relationships between physical or sexual abuse and aggression [5,6] and relationships between CEM and aggression have also been confirmed by some studies [7], while the pathways from CEM to aggression remain unclear, particularly in the Chinese cultural context. Attachment theory posits that early interactions between a child and caregiver(s) may influence individuals’ internal working models about themselves, others, and interpersonal relationships, which may influence later development [8]. Guided by attachment theory, therefore, the current study attempted to explore relationships between CEM and aggression and to examine the pathways from CEM to aggression in the Chinese cultural context.

1.1. Childhood Emotional Maltreatment and Aggression

CEM refers to the hostile rejecting of the child, degrading, corrupting, or denying emotional responsiveness, or failing to provide for the child’s emotional needs [9], which may contribute to later maladaptation, such as aggression. For example, a study reported that CEM was positively associated with aggression in a sample of Chinese college students [10]. Another study confirmed these relationships based on 1266 Chinese college students [11]. Moreover, some studies found these relationships in samples of Chinese adolescents [7,12]. Similarly, these relationships between CEM and aggression have also been confirmed in Western adult samples [13,14]. Additionally, A study reported that relationships between childhood maltreatment and aggression were not influenced by types of childhood maltreatment based on a meta-analysis [15], while other study found that emotional maltreatment was more related to internalizing than externalizing behaviors (e.g., aggression) in Chinese samples based on a meta-analysis [16]. A study reported that CEM did not predict individuals’ aggression based on a longitudinal study [17].

Although several studies have explored relationships between CEM and aggression, this topic still needs further exploration. Individuals who have suffered CEM may be inefficient in emotional regulation and raise their selective attention to threat-related signals (i.e., anger-related signals), which may contribute to low levels of control of feelings such as anger [9,18], and these emotional dysregulations and disorganized anger may lead to high levels of aggression [19]. Meanwhile, a study suggested that individuals who had experienced CEM had some negative schemas, such as mistrust, self-sacrifice, and emotional inhibition, which may lead to high levels of aggression [20]. The college period is one of the most important periods in a person’s life, and experiences in childhood may have more effects on individuals’ development in this period. Similarly, being a college student may be an important component for social development, particularly in developing countries, which suggests that we should pay attention to college students’ individual development, such as aggression. The current study, therefore, attempted to explore the relationships between CEM and aggression in the Chinese cultural context. We hypothesized that CEM would be found to have a positive relationship with aggression in a sample of Chinese college students.

1.2. Resilience and Self-Esteem as Mediators

Resilience is an ability that helps people master normative developmental tasks despite significant negative experiences [21], and this ability may be influenced by adverse childhood experiences [22,23]. For example, a study reported that Chinese college students who have experienced childhood maltreatment might have low levels of resilience [24]. A study found that emotional maltreatment was negatively associated with resilience in a sample of Chinese college students [25]. Similarly, relationships between childhood maltreatment and aggression have also been confirmed in Western samples based on longitudinal designs [26]. Moreover, relationships between resilience and aggression have been explored by some studies. For instance, a study found that resilience was negatively associated with aggression in a sample of Chinese college students [23]. Further, a study confirmed these relationships in a sample of Western adolescents [27]. Additionally, a meta-analysis also confirmed the relationships between adverse childhood experiences and resilience [28].

Meanwhile, self-esteem (SE), including positive or negative evaluations about oneself, is an important construct in individuals’ development [29], and it may be influenced by adverse childhood experiences. Some studies have explored relationships between child maltreatment and self-esteem. For example, a study reported that childhood maltreatment was negatively associated with self-esteem in 324 Chinese college students [30]. A study found that emotional maltreatment was negatively associated with self-esteem in a sample of Chinese college students [31]. These relationships were also confirmed in Chinese adolescents and Western young adults [32,33]. Similarly, some studies suggested that low levels of self-esteem may be associated with aggression [34,35].

Although relationships between child maltreatment, aggression, resilience, and self-esteem have been explored by some studies, roles of resilience and self-esteem in the relationships between child maltreatment and aggression need further exploration, particularly in the relationships between CEM and aggression. Moreover, resilience and self-esteem have been found to mediate the relationships between child maltreatment and later development, respectively [6,36], which suggests that resilience and self-esteem may be potential mediators in adverse childhood experiences and later maladaptation [37,38]. Therefore, the current study attempted to examine roles of resilience and self-esteem in the relationships between CEM and aggression. Additionally, CEM, a kind of adverse childhood experiences, influences the development of self and relationships with others (e.g., low levels of self-esteem and resilience; [28,30]), and this biased self and these relationships with others may be bridges for later maladaptation. Therefore, the current study attempted to explore roles of resilience and self-esteem in the relationships between CEM and aggression. We hypothesized that resilience and self-esteem would be found to parallel mediate relationships between CEM and aggression in a sample of Chinese college students.

2. The Current Study

Although relationships between CEM and aggression have been explored by some studies, the pathways from CEM to aggression still need further exploration. Among countries, China has the largest population in the world, and Chinese behaviors may be influenced by the traditional Chinese culture, which emphasizes hierarchy in families, which may raise the importance of exploring CEM. What relationships between CEM and aggression are and how CEM influences aggression may be two important issues for child maltreatment studies in the Chinese cultural context. The current study, therefore, attempted to (a) explore relationships between CEM and aggression, and (b) examine roles of resilience and self-esteem in relationships between CEM and aggression in a sample of Chinese college students. We hypothesized that CEM would be found to have a positive relationship with aggression, and resilience and self-esteem would parallel mediate the relationships between CEM and aggression in a sample of Chinese college students. Specifically, individuals who have experienced CEM may have high levels of aggression, and high levels of resilience and self-esteem may decrease the effects of CEM on aggression in a sample of Chinese college students.

3. Method

3.1. Participants

A total of 809 college students were recruited from three universities in Liaoning Province of China with convenience sampling techniques in December, 2021. The mean age of participants was 19.07 years (SD = 1.17), and 76.5% (619/809) of them were women. A total of 61.20% (495/809) of them were the only child in their family. The detailed demographic information is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Basic information of participants (n = 809).

3.2. Measures

The Childhood Trauma Questionnaire—Short Form (Supplementary File S1) (CTQ-SF; [39]).

The CTQ-SF, a 28-item self-reported screening tool, has been used to assess childhood maltreatment widely. It has five subscales, namely physical abuse (e.g., Punished with a belt), emotional abuse (e.g., Called names), sexual abuse (e.g., Touched in a sexual way), physical neglect (e.g., Wear dirty clothes), and emotional neglect (e.g., Loved each other). Each item is rated via a five-point Likert scale (from 1 = never to 5 = always), and high scores indicate high levels of childhood maltreatment. The Chinese adaptation of the CTQ-SF was developed by Zhao and colleague [40], and has been used widely in the Chinese cultural context [41]. The subscales of emotional abuse (EA) and emotional neglect (EN) were administered in the current study to assess CEM in Chinese college students, and Cronbach’s alpha was 0.75 and 0.84, respectively.

The Aggression Questionnaire (Supplementary File S2) (AQ; [42]).

The AQ, a 29-item self-reported scale that has been used to assess aggression, has been adapted into Chinese by Li and colleague [43] with five subscales, namely physical aggression (e.g., I have threatened people I know), verbal aggression (e.g., My friends say that I am somewhat argumentative), anger (e.g., Some of my friends think I am a hothead), hostility (e.g., I am sometimes eaten up with jealousy), and self-aggression (e.g., I have harmed myself). Each item is responded via a five-point Likert scale (from 1 = not at all characteristic to 5 = very characteristic), and high scores indicate high levels of aggression. The Chinese version of the AQ has been widely used in Chinese samples [44]. The subscales of physical aggression (PA), verbal aggression (VA), anger (AN), and hostility (HO) were used in the current study to assess the levels of aggression in Chinese college students, and Cronbach’s alpha was 0.72, 0.83, 0.81, and 0.71, respectively.

Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (Supplementary File S3) (SES; [45]).

The SES, a 10-item self-reported questionnaire that has been used to assess individuals’ self-esteem, has been widely used in the Chinese cultural context [46]. Participants rate each item on a four-point Likert scale (from 1 = very low conformity to 4 = very high conformity), and high scores indicate high levels of self-esteem (SE). The Chinese version of SES was administered in the current study to assess the levels of self-esteem in Chinese college students, and Cronbach’s alpha was 0.92.

The Chinese Adolescents Resilience Scale (Supplementary File S4) (CARS; [47]).

The CARS, a 27-item self-reported scale that has been used to assess individuals’ resilience, contains five subscales, namely the goal-focused (e.g., My life has clear purposes), emotional control (e.g., I am always discouraged by failures), positive cognition (e.g., I think adversity motivate me), family support (e.g., My parents respect my opinions), and interpersonal assistance subscales (e.g., I will ask for help when facing difficulties). Each item is rated via a five-point Likert scale (from 1 = very low conformity to 5 = very high conformity), and high scores indicate high levels of resilience. The CARS was administered in the current study to assess levels of resilience in Chinese college students, and Cronbach’s alpha was 0.85.

3.3. Procedure

There were several steps for collecting data in the current study. First, the first author presented the aims and processes of the current study to four potential cooperators, and three of them agreed to collect data in their universities. Second, the authors, respectively, went to these three universities and sent questionnaires to 900 participants initially. All participants were informed about the research before data collection process, and signed informed consent attached at the beginning of the measurement booklets, which informed them about the purposes of the study and assured them that their answers would only be used anonymously for research purposes. Third, all participants completed questionnaires in classrooms within 20 min, and all of them received a small gift worth 5 RMB (USD 0.74). Fourth, the research assistants and the authors completed the data cleaning and analysis.

3.4. Ethical Approval

The study was approved by the ethics committee of Faculty of Education, Beijing Normal University, China, and all materials and procedures were safe for participants.

3.5. Data Analysis

First, missing values and outliers were examined before data analysis, and questionnaires with 15% missing data were removed in data analysis [48]; a total of 809 participants were included in data analysis process. Second, a Pearson correlation analysis was used to examine relationships between all variables. Third, the direct effect model of the structural equation modeling (SEM) was performed to examine relationships between CEM and aggression. Fourth, the mediating effects models of resilience and self-esteem were examined by SEM, and Bootstrapping method with 1000 times repeated-sampling was used to examine mediating effects. All analyses were conducted by IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 22.0 [49] and IBM SPSS AMOS for Windows, Version 22.0 [50], and all tests were two-tailed for significance with p value set at 0.05. Moreover, multiple model fit indexes were used to compare models in the current study, including root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA, 0.080 or less), standardized root-mean-square-residual (SRMR, 0.080 or less), comparative fit index (CFI, 0.900 or more), normative fit index (NFI, 0.900, or more), goodness fit index (GFI, 0.900 or more), and Tucker–Lewis index (TLI, 0.900 or more) [51].

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Analysis

Descriptive statistics and correlations are presented in Table 2. As indicated, CEM was positively associated with aggression (r = 0.41, p < 0.01), and was negatively associated with resilience (r = −0.56, p < 0.01) and self-esteem (r = −0.10, p < 0.01). Aggression was negativity associated with resilience (r = −0.44, p < 0.01) and self-esteem (r = −0.17, p < 0.01).

Table 2.

Means, standard deviations, and correlations between all variables (n = 809).

4.2. Effects of Childhood Emotional Maltreatment on Aggression

Average scores were used to determine CEM, self-esteem, resilience and aggression constructs, and all coefficients were standardized estimates. SEM was used to measure the direct relationship between CEM and aggression. The results of the SEM indicated that CEM was positively associated with aggression (β = 0.43, SE = 0.031, p < 0.001). Further, the model showed an acceptable fit to the data [52] (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Mediation effects of childhood emotional maltreatment on aggression via resilience and self-esteem (n = 809).

4.3. Mediation Analysis

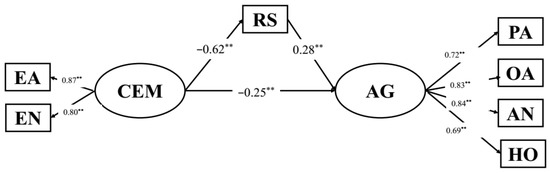

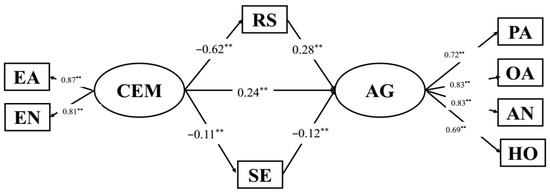

SEM was used to measure the indirect relationships among CEM, resilience, self-esteem and aggression. Further, the Bootstrapping method was used to examine the mediating effects. The SEM results showed that the structural model provided a good fit to the data (see Table 3). The SEM results indicating the relationships between variables are presented in Figure 1 and Figure 2.

Figure 1.

Standardized parameter estimates of the structural model demonstrating effects of CEM on aggression via resilience. Note: N = 809; EA: emotional abuse; EN: emotional neglect; PA: physical aggression; VA: verbal aggression; AN: anger; HO: hostility; CEM: childhood emotional maltreatment; AG: aggression; RS: resilience, ** p < 0.01.

Figure 2.

Standardized parameter estimates of the structural model demonstrating effects of CEM on aggression via resilience and self-esteem. Note: N = 809; EA: emotional abuse; EN: emotional neglect; PA: physical aggression; VA: verbal aggression; AN: anger; HO: hostility; CEM: childhood emotional maltreatment; AG: aggression; RS: resilience; SE: self-esteem, ** p < 0.01.

In this mediation model (Figure 2), CEM was negatively associated with resilience (β = −0.62, p < 0.001) and self-esteem (β = −0.11, p < 0.01), and was positively associated with aggression (β = 0.24, p < 0.001). Resilience was negatively associated with aggression (β = −0.28, p < 0.001). Furthermore, self-esteem was negatively associated with aggression (β = −0.12, p < 0.001). Both of the 95% confidence intervals of direct and indirect effects did not include 0 (see Table 3). Thus, resilience and self-esteem partially mediated the relationships between CEM and aggression in Chinese college students.

5. Discussion

The current study explored relationships between CEM and aggression and examined roles of resilience and self-esteem in those relationships in the Chinese cultural context, which may broaden the scope of child maltreatment studies within multiple cultures and provide possible explanations of pathways from CEM to aggression. The findings highlight the importance of increasing levels of resilience and self-esteem of survivors of CEM in the Chinese cultural context.

The results showed that CEM was significantly positively associated with aggression, findings which were consistent with previous studies [11,15,16]. Individuals who have suffered CEM may have difficulty in emotional regulation for improper or deficit emotional interactions with caregivers [53], and they may have a hyperactive amygdale, which may contribute to high levels of aggression [54]. Moreover, they may have insecure attachment with their caregivers, which may establish biased internal working models about interpersonal relationships [55,56]. Additionally, while Chinese people may be different from Western people, the findings in the present study may suggest that relationships between CEM and aggression exist across nations and cultures.

Moreover, the results showed that CEM was negatively associated with resilience and self-esteem, findings which were consistent with previous studies [24,28,31]. Individuals who have experienced CEM may feel more loneliness [57] and they may have less skills to communicate with others [58], which may contribute to their low levels of resilience. Meanwhile, individuals who have experienced CEM may be estranged to others or have social anxiety about their communication skills [59], and they may not have the ability to judge whether the behaviors towards or evaluations about them from their caregivers are right or not, which may contribute to their improper evaluations or ideas of themselves [60]. Similarly, individuals that suffered CEM may have disorganized attachment with their caregivers, which may contribute to their biased evaluations of self, such as low levels of self-esteem [61].

Furthermore, the results demonstrated that resilience and self-esteem parallel mediated the relationships between CEM and aggression, suggesting that CEM not only has direct effects on aggression, but also has indirect effects though resilience and self-esteem. These results also suggested that resilience and self-esteem may play roles in the relationships between child maltreatment and later development, which has also been suggested by the results previous studies [6,38]. Moreover, Chinese people prefer constructing a self based on interpersonal relationships [62], which may contribute to severe impacts of CEM on resilience and self-esteem. Survivors of CEM with high levels of resilience and self-esteem may overcome the influence of CEM, which may contribute to low levels of aggression. These findings suggest that strategies for increasing resilience and self-esteem should be conducted to help survivors of CEM overcome the impact of CEM on later development in the Chinese cultural context.

5.1. Limitations

Several limitations should be acknowledged in this study. First, a retrospective study design and self-reported scales were used, which may have influenced the accuracy of information. Future research should take participants’ age and memory biases into consideration, and collect data based on several resources (e.g., peers, parents, and teachers). Second, the current study used convenience sampling techniques to recruit the participants, which may not have been a representative sample. Future studies should recruit participants based on random sampling or stratified sample techniques. Third, a cross-sectional design was used to examine the pathways from CEM to aggression, which may not have provided solid evidence for mechanisms linking CEM to aggression. Longitudinal studies should be conducted in the future to confirm the results of the current study. Fourth, the participants were recruited from China, and Chinese people may be quite different to Western cultures, which may influence the ability of the results to be generalized to all cultural contexts. Future studies should recruit participants from different cultural contexts and examine the relationships between CEM and aggression across nations and cultures. Fifth, individuals who have experienced CEM may have poor academic achievement, which may contribute to their low levels of education. The current study explored relationships between CEM, aggression, self-esteem, and resilience in a sample of Chinese college students, which may not provide the whole picture of those relationships. Future studies should recruit non-university adolescents or young adults, which may help us better understand the pathways from CEM to aggression.

5.2. Strengths

Although the current study had several limitations, it also had several strengths. First, the study verified relationships between CEM and aggression in a sample of Chinese college students, which may broaden the scope of childhood maltreatment studies across nations and cultures. Second, the study examined roles of resilience and self-esteem in the relationships between CEM and aggression, which may provide possible mechanisms linking childhood maltreatment to later development. Third, the study may provide possible strategies for CEM interventions in college students.

5.3. Practical Implications

Keeping the limitations and strengths of the current study in mind, its implications should be also acknowledged. First, the results showed that CEM was positively associated with aggression in college students, which suggests that CEM may have a long-term effect on individuals’ later development. Governments and communities should provide support for positive parenting behaviors of Chinese parents and decrease the prevalence of CEM in the Chinese population. Second, the results showed that resilience and self-esteem parallel mediated the relationships between CEM and aggression, which suggests that resilience and self-esteem may be possible mediators of pathways from CEM to aggression. Schools should provide strategies for increasing levels of resilience and self-esteem in survivors of CEM. For example, schools should provide courses about communication skills, which may increase levels of communication skills in survivors of CEM, and in turn, contribute to high levels of resilience. Additionally, teachers may give more positive feedback to survivors of CEM and help them rebuild their evaluations of self, which may increase levels of self-esteem in survivors of CEM.

6. Conclusions

The current study explored relationships between CEM and aggression and examined the roles of resilience and self-esteem in those relationships in a sample of Chinese college students, which may broaden the scope of childhood maltreatment studies across nations and cultures and may provide possible mechanisms linking childhood maltreatment to later development in the Chinese cultural context. The results showed that childhood emotional maltreatment was positively associated with aggression and negatively associated with resilience and self-esteem. Moreover, resilience and self-esteem parallel mediated the relationships between childhood emotional maltreatment and aggression, a finding which was in line with the hypothesis. The findings underscore the importance of enhancing resilience and self-esteem in interventions designed to reduce the aggression of college students who were emotionally maltreated in childhood in the Chinese cultural context.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/bs12100383/s1, Supplementary File S1: The Childhood Trauma Questionnaire–Short Form; Supplementary File S2: The Aggression Questionnaire; Supplementary File S3: Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale; Supplementary File S4: The Chinese Adolescents Resilience Scale.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.C.; Data curation, J.J. and Y.H.; Formal analysis, C.C.; Funding acquisition, C.C.; Investigation, S.J.; Methodology, Y.H.; Resources, J.J.; Supervision, C.C.; Writing—original draft, C.C., J.J. and S.J.; Writing—review & editing, C.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China [21YJC880005] and Department of Education of Guangdong province [2021GXJK199] and Beijing Normal University at Zhuhai [28817–11032102].

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Faculty of Education, Beijing Normal University, China (protocol code BNU202111100034 and date of approval 8 December 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank all students who participated in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ainsworth, M.D. Infant mother attachment. Am. Psychol. 1979, 34, 932–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, B. Childhood psychological abuse and adult aggression: The mediating role of self-capacities. J. Interpers. Violence 2011, 26, 2093–2110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amad, S.; Gray, N.S.; Snowden, R.J. Self-esteem, narcissism, and aggression: Different types of self-esteem predict different types of aggression. J. Interpers. Violence 2021, 36, 13296–13313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Augsburger, M.; Basler, K.; Maercker, A. Is there a female cycle of violence after exposure to childhood maltreatment? A meta-analysis. Psychol. Med. 2019, 49, 1776–1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernstein, D.P.; Stein, J.A.; Newcomb, M.D.; Walker, E.; Pogge, D.; Ahluvalia, T. Development and validation of a brief screening version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. Child Abus. Negl. 2003, 27, 169–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bijlsma, A.M.E.; Assink, M.; Overbeek, G.; Geffen, M.V.; Put, V.D.C.E. Differences in developmental problems between victims of different types of child maltreatment. J. Public Child Welf. 2022, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodski, S.K.; Hutz, C.S. The repercussions of emotional abuse and parenting styles on self-esteem, subjective well-being: A retrospective study with university students in Brazil. J. Aggress. Maltreatment Trauma 2012, 21, 256–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buss, A.H.; Perry, M. The aggression questionnaire. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1992, 63, 452–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carli, V.; Mandelli, L.; Zaninotto, L.; Alberti, S.; Roy, A.; Serretti, A.; Sarchiapone, M. Trait-aggressiveness and impulsivity: Role of psychological resilience and childhood trauma in a sample of male prisoners. Nord. J. Psychiatry 2014, 68, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C. The Relationship among Emotional Maltreatment, Aggression, Resilience and Peer Relations within 4–6grade Pupils. Master’s Thesis, Shenyang Normal University, Shenyang, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C. The Developmental Trajectories and Factors of Child Maltreatment and Relations with Behavior Problems. Ph.D. Thesis, Zhejiang Normal University, Jinhua, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.; Guo, L.; Wang, B. The self-esteem as a mediator in the relationship between childhood emotional maltreatment and aggression. Chin. J. Sch. Health 2015, 36, 1088–1090. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.; Qin, J. Childhood physical maltreatment and aggression among Chinese young adults: The roles of resilience and self-esteem. J. Aggress. Maltreatment Trauma 2020, 29, 1072–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Liu, A.; Wu, H. Mediating effect of self-concealment on relationship between psychological abuse and loneliness in high school students. Chin. Ment. Health J. 2018, 32, 432–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, E.; Wright, M.O. The Impact of Childhood Psychological Maltreatment on Interpersonal Schemas and Subsequent Experiences of Relationship Aggression. J. Emot. Abus. 2007, 7, 93–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crow, T.; Cross, D.; Powers, A.; Bradley, B. Emotion dysregulation as a mediator between childhood emotional abuse and current depression in a low-income African-American sample. Child Abus. Negl. 2014, 38, 1590–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, N.; Liu, J. Physical abuse, emotional abuse, and neglect and childhood behavior problems: A meta-analysis of studies in mainland China. Trauma Violence Abus. 2018, 21, 206–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dambacher, C.; Kreutz, J.; Titze, L.; Lutz, M.; Franke, I.; Streb, J.; Dudeck, M. Resilience as a mediator between adverse childhood experiences and aggression perpetration in forensic inpatients: An exploratory study. J. Aggress. Maltreatment Trauma 2021, 31, 910–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davey, A.; Savla, J. Statistical Power Analysis with Missing Data: A Structural Equation Modeling Approach; Routledge Taylor & Francis Group: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, C.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, L. Relationship among explicit and implicit self-esteem discrepancy of self-esteem and aggressive in college students. Chin. Ment. Health J. 2020, 34, 686–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertürk, İ.Ş.; Kahya, Y.; Gör, N. Childhood Emotional Maltreatment and Aggression: The Mediator Role of the Early Maladaptive Schema Domains and Difficulties in Emotion Regulation. J. Aggress. Maltreatment Trauma 2020, 29, 92–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabala, M.K.; Rroth, M.R.; Thompson, M.P.; Kaslow, N.J. Children’ emotional abuse and relational functioning: Social support and internalizing symptoms as moderators. J. Child Adolesc. Trauma 2009, 2, 179–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gay, L.E.; Harding, H.G.; Jackson, J.L.; Burns, E.E.; Baker, B.D. Attachment style and early maladaptive schemas as mediators of the relationship between childhood emotional abuse and intimate partner violence. J. Aggress. Maltreatment Trauma 2013, 22, 408–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Díez, Z.; Orue, I.; Calvete, E. The role of emotional maltreatment and looming cognitive style in the development of social anxiety symptoms in late adolescents. Anxiety Stress Coping 2016, 30, 26–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greger, H.K.; Myhre, A.K.; Klöckner, C.A.; Jozefiak, T. Childhood maltreatment, psychopathology and well-being: The mediator role of global self-esteem, attachment difficulties and substance use. Child Abus. Negl. 2017, 70, 122–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, L.; Chen, C. Relationships between childhood sexual abuse and aggression among undergraduate students: Mediating effect of resilience. Chin. J. Public Health 2015, 31, 1453–1457. [Google Scholar]

- Van Harmelen, A.-L.; Van Tol, M.-J.; Demenescu, L.R.; Van Der Wee, N.J.A.; Veltman, D.J.; Aleman, A.; Van Buchem, M.A.; Spinhoven, P.; Penninx, B.W.J.H.; Elzinga, B.M. Enhanced amygdala reactivity to emotional faces in adults reporting childhood emotional maltreatment. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 2013, 8, 362–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, N.; Xiang, Y. How child maltreatment impacts internalized/externalized aggression among Chinese adolescents from perspectives of social comparison and the general aggression model. Child Abus. Negl. 2021, 117, 105024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hébert, M.; Langevin, R.; Oussaïd, E. Cumulative childhood trauma, emotion regulation, dissociation, and behavior problems in school-aged sexual abuse victims. J. Affect. Disord. 2017, 225, 306–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Gan, Y. Development and psychometric validity of resilience scale for Chinese adolescents. Acta Psychol. Sin. 2008, 40, 902–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 22.0; IBM Corp.: Armonk, NY, USA, 2013.

- IBM SPSS AMOS for Windows, Version 22.0; IBM Corp.: Armonk, NY, USA, 2018.

- Jaffee, S.R.; Caspi, A.; Moffitt, T.E.; Polo-Tomas, M.; Taylor, A. Individual, family, and neighborhood factors distinguish resilient from non-resilient maltreated children: A cumulative stressors model. Child Abus. Negl. 2007, 31, 231–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, G.; Wang, Y. Childhood psychological abuse and aggression: A multiple mediating model. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 2017, 25, 691–696. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.; Cicchetti, D. A longitudinal study of child maltreatment, mother–child relationship quality and maladjustment: The role of self-esteem and social competence. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2004, 32, 341–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practices of Structural Equation Modeling; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Fei, L.; Zhang, Y. Development, reliability and validity of the Chinese version of Buss & Perry Aggression Questionnaire. Chin. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2011, 37, 607–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Zhang, S.; Wu, Z. Relationship among social anxiety, emotional maltreatment and resilience in rural college students with left-behind experience. Chin. Ment. Health J. 2019, 33, 64–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Qi, G.; Bi, T.; Tang, H.; Zhu, Q.; Liu, Z. Association between childhood psychological maltreatment and aggressive behavior of medical freshmen: A mediated moderating effect. China J. Health Psychol. 2022, 13, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, F. The Association between child abuse and college students’ coping styles: The mediating role of self-esteem. Psychol. Tech. Appl. 2019, 7, 620–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markus, H.R.; Kitayama, S. Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychol. Rev. 1991, 98, 224–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McRae, E.M.; Stoppelbein, L.; O’Kelley, S.E.; Fite, P.K.; Smith, S.B. Pathways from child maltreatment to proactive and reactive aggression: The role of posttraumatic stress symptom clusters. Psychol. Trauma Theory Res. Pract. Policy 2022, 14, 357–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, C.A.; Chang, Y.; Choy, O.; Tsai, M.C.; Hsieh, S. Adverse childhood experiences are associated with reduced psychological resilience in youth: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Children 2022, 9, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishimi, K.; Choi, K.W.; Davis, K.A.; Powers, A.; Bradley, B.; Dunn, E.C. Features of childhood maltreatment and resilience capacity in adulthood: Results from a large community-based sample. J. Trauma. Stress Oct. 2020, 33, 665–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, R.; Ang, R.P.; Ho, M.-H.R. Coping with anxiety, depression, anger and aggression: The mediational role of resilience in adolescents. Child Youth Care Forum 2012, 41, 529–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, M. Society and the Adolescent Self-Image; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Stoltenborgh, M.; Bakermans-Kranenburg, M.J.; Alink, L.R.; IJzendoorn, M.H. The universality of childhood emotional abuse: A meta-analysis of worldwide prevalence. J. Aggress. Maltreatment Trauma 2012, 21, 870–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Du, H.; Niu, G.; Li, J.; Hu, X. The association between psychological abuse and neglect and adolescents’ aggressive behavior: The mediating and moderating role of the moral disengagement. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 2017, 33, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, A.; Poon, L.; Kumari, V.; Cleare, A.J. Fear biases in emotional face processing following childhood trauma as a marker of resilience and vulnerability to depression. Child Maltreatment 2015, 20, 240–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thoma, M.V.; Bernays, F.; Eising, C.M.; Maercker, A.; Rohner, S.L. Child maltreatment, lifetime trauma, and mental health in Swiss older survivors of enforced child welfare practices: Investigating the mediating role of self-esteem and self-compassion. Child Abus. Negl. 2021, 113, 104925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. Child Maltreatment 2015; HHS: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. Available online: https://www.acf.hhs.gov/cb/resource/child-maltreatment-2015 (accessed on 28 May 2020).

- Wang, S.; Xu, H.; Zhang, S.; Wan, Y.; Tao, F. Mediating effects of self-esteem in the relationship between childhood maltreatment and non-suicidal self-injury among adolescents: The roles of sex and only-child status. Soc. Sci. Med. 2020, 249, 112847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, N.M.; Elklit, A. Child maltreatment and disordered eating in adulthood: A mediating role of PTSD and self-esteem? J. Child Adolesc. Trauma 2020, 13, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Y.; Chen, Z.; Zhao, J. How childhood maltreatment impacts aggression from perspectives of social comparison and resilience framework theory. J. Aggress. Maltreatment Trauma 2020, 29, 1113–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Wang, N.; Gao, L.; Wang, X. Childhood maltreatment and adolescents’ cyberbullying perpetration: The roles of self-esteem and friendship quality. J. Psychol. Sci. 2021, 44, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, T.X.; Liu, W.; Liu, F.; Che, H. Relationship between psychological maltreatment and aggressive behavior of children aged 8~12: The mediating role of cognitive reappraisal. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 2021, 29, 282–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaff, J.F.; Hair, E. Positive development of the self: Self-concept, self-esteem, and identity. In Well-Being: Positive Development across the Life Course; Bornstein, M.H., Davidson, L., Keyes, C.L.M., Moore, K.A., Eds.; Psychology Press: London, UK, 2003; pp. 235–250. [Google Scholar]

- Zhan, J.; Peng, X.; Chao, X.; Xiang, Y. Childhood maltreatment influences mental symptoms: The mediating roles of emotional intelligence and social support. Front. Psychiatry 2019, 10, 415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Zhang, Y.; Li, L. Reliability and validity of the Chinese version of childhood trauma questionnaire. Chin. J. Tissue Eng. Res. 2005, 9, 105–107. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; Xu, W. Childhood trauma and negative emotions among college students with left-behind experience: The moderation of resilience. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 2022, 38, 584–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Chen, X.; Luo, F.; Yang, Y.; Yang, Z. Emotional maltreatment and social anxiety in rural college students with left-behind experience: The mediation effect of self-esteem and self-acceptance. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 2022, 30, 630–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).