Psychopathological Impact and Resilient Scenarios in Inpatient with Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorders Related to Covid Physical Distancing Policies: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Delusions

- Hallucinations

- Disorganized speech

- Disorganized (or catatonic) behavior

- Negative symptoms [1]

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Objective of the Research

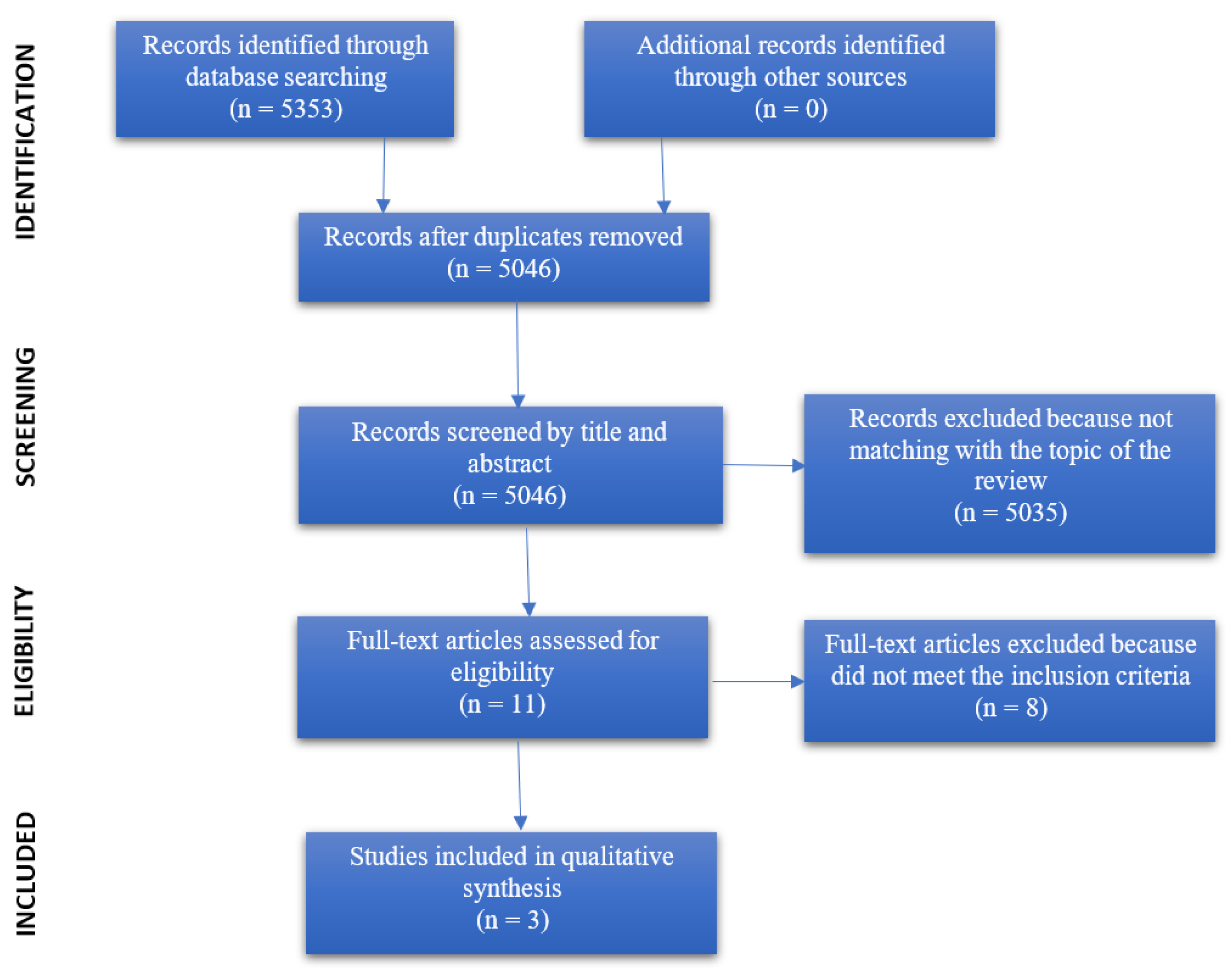

2.2. Literature Search and Selection

2.3. Eligibility Criteria

- Participants: patients with schizophrenia.

- Intervention: effects of COVID-19 physical distancing policies on symptomatology.

- Comparison: symptomology before the COVID-19 pandemic.

- Outcome: exacerbation or decrease of positive, negative, and disorganized symptomatology.

- Study design: experimental studies, longitudinal studies.

2.4. Data Extraction

2.5. Risk of Bias Assessment

3. Results

3.1. Schizophrenic Symptomatology

3.2. Other Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kring, A.M.; Johnson, S.L.; Davison, G.C.; Neale, J.M. Schzofrenia. In Psicologia Clinica, 5th ed.; Zanichelli: Bologna, Italy, 2017; pp. 247–280. [Google Scholar]

- Marmarosh, C.L.; Forsyth, D.R.; Strauss, B.; Burlingame, G.M. The Psychology of the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Group-Level Perspective. Group Dyn. Theory Res. Pract. 2020, 24, 122–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Lin, D.; Operario, D. Need for a Population Health Approach to Understand and Address Psychosocial Consequences of COVID-19. Psychol. Trauma Theory Res. Pract. Policy 2020, 12, S25–S27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fineberg, N.A.; Van Ameringen, M.; Drummond, L.; Hollander, E.; Stein, D.J.; Geller, D. How to manage obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) under COVID-19: A clinician’s guide from the International College of Obsessive Compulsive Spectrum Disorders (ICOCS) and the Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders Research Network (OCRN) of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology. Compr. Psychiatry 2020, 100, 152174. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Farhan, R.; Llopis, P. Psychiatric and neuropsychiatric syndromes and COVID-19. Lancet Psychiatry 2020, 7, 736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gimenez-LIort, L.; Alveal-Mellado, D. Digging Signatures in 13-Month-Old 3xTg-AD Mice of Alzheimer’s Disease and Its Disruption by Isolation Despite Social Life Since They Were Born. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2021, 14, 611384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfefferbaum, B.; North, C.S. Mental Health and the Covid-19 Pandemic. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 510–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinn, A.K.; Viron, M. Perspectives on the COVID-19 pandemic and individuals with serious mental illness. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2020, 81, e1–e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, E.; Gray, R.; Monaco, S.L.; O’Donoghue, B.; Nelson, B.; Thompson, A. The potential impact of COVID-19 on psychosis: A rapid review of contemporary epidemic and pandemic research. Schizophr. Res. 2020, 222, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiang, Y.T.; Zhao, Y.J.; Liu, Z.H.; Li, X.H.; Zhao, N.; Cheung, T.; Ng, C.H. The COVID-19 outbreak and psychiatric hospitals in China: Managing challenges through mental health service reform. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2020, 16, 1741–1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Zhang, Y. Mental healthcare for psychiatric inpatients during the COVID-19 epidemic. Gen. Psychiatry 2020, 33, e100216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khosoravi, M. COVID-19 Pandemic: What are the Risks and Challenges for Schizophrenia? Clin. Schizophr. Relat. Psychoses 2020, 14, 58–59. [Google Scholar]

- Le Corre, P.; Loas, G. Repurposing functional inhibitors of acid sphingomyelinase (fiasmas): An opportunity against SARS-CoV-2 infection? Clin. Pharm. Ther. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinkham, A.E.; Ackerman, R.A.; Depp, C.A.; Harvey, P.D.; Moore, R.C. A Longitudinal Investigation of the Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Mental Health of Individuals with Pre-existing Severe Mental Illnesses. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 294, 113493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, J.; Hua, T.; Zeng, K.; Zhong, B.; Wang, G.; Liu, X. Influence of social isolation caused by coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) on the psychological characteristics of hospitalized schizophrenia patients: A case-control study. Transl. Psychiatry 2020, 10, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quittkat, H.L.; Düsing, R.; Holtmann, F.J.; Buhlmann, U.; Svaldi, J.; Vocks, S. Perceived Impact of Covid-19 Across Different Mental Disorders: A Study on Disorder-Specific Symptoms, Psychosocial Stress and Behavior. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 586246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Authors | Year | Title | Country | Study Design | Total Sample | Instruments | Results |

| Amy E. Pinkham, Robert A. Ackerman, Colin A. Depp, Philip D. Harvey, Raeanne C. Moore | 2020 | A Longitudinal Investigation of the Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Mental Health of Individuals with Pre-existing Severe Mental Illnesses | USA | Longitudinal study | 148 individuals suffering from serious mental illness; 92 individuals suffering from schizophrenia | PANSS, MADRS, YMRS, SUMD, EMA questionnaire | Contrary to expectations, there were no significant changes in positive, negative, or disorganized symptomatology compared with the pre-pandemic situation. In contrast, there is a significant increase in well-being in the early pandemic period. |

| Jun Ma, Tingting Hua, Kuan Zeng, Baoliang Zhong, Gang Wang, Xuebing Liu | 2020 | Influence of social isolation caused by coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) on the psychological characteristics of hospitalized schizophrenia patients: a case-control study | China | Case-control study | 30 patients with schizophrenia subjected to isolation as the experimental group; 30 patients with schizophrenia not subjected to isolation as the control group | CPSS, PANSS, HAMD, HAMA, PSQI | The results of the study show that patients in isolation experience higher levels of stress, anxiety, and depressive symptomatology, compared to patients not in isolation. However, PANSS scale scores between the two groups are not significantly different, meaning that no relevant changes in schizophrenic symptomatology are detected. |

| Authors | Year | Title | Country | Study Design | Total Sample | Instruments | Results |

| Hannah L. Quittkat, Rainer Düsing, Friederike-Johanna Holtmann, Ulrike Buhlmann, Jennifer Svaldi, Sija Vocks | 2020 | Perceived Impact of Covid-19 Across Different Mental Disorders: A Study on Disorder-Specific Symptoms, Psychosocial Stress and Behavior | Germany | Quantitative research (questionnaire) | 2233 individuals diagnosed with mental illness. 6 individuals having schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders. | FKS, CAHSA, DASS-D, EDE-Q, PHQ, PSWQ-d, SIAS, SPS, WI, Y-BOCS | Psychotic symptoms, compared to the pre-pandemic situation, do not appear to have undergone any modification. However, this could be due to the very small sample (only 6 individuals). |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Caponnetto, P.; Benenati, A.; Maglia, M.G. Psychopathological Impact and Resilient Scenarios in Inpatient with Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorders Related to Covid Physical Distancing Policies: A Systematic Review. Behav. Sci. 2021, 11, 49. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs11040049

Caponnetto P, Benenati A, Maglia MG. Psychopathological Impact and Resilient Scenarios in Inpatient with Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorders Related to Covid Physical Distancing Policies: A Systematic Review. Behavioral Sciences. 2021; 11(4):49. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs11040049

Chicago/Turabian StyleCaponnetto, Pasquale, Alessandra Benenati, and Marilena G. Maglia. 2021. "Psychopathological Impact and Resilient Scenarios in Inpatient with Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorders Related to Covid Physical Distancing Policies: A Systematic Review" Behavioral Sciences 11, no. 4: 49. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs11040049

APA StyleCaponnetto, P., Benenati, A., & Maglia, M. G. (2021). Psychopathological Impact and Resilient Scenarios in Inpatient with Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorders Related to Covid Physical Distancing Policies: A Systematic Review. Behavioral Sciences, 11(4), 49. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs11040049