Meaning-Making Coping Methods among Bereaved Parents: A Pilot Survey Study in Sweden

Abstract

:1. Introduction

Conceptual Framework

In more secular terms, the process of giving a special meaning to objects may well be encompassed by Winnicott’s (1971) intermediate area as well as attribution theory (Fölsterling, 2001). According to Winnicott and object-relational theory, people are, from early childhood to death, able to “play with reality” (Salander, 2012). The intermediate area is the mental area of human creation: in childhood in the doll’s house or sandpit, in adulthood in the area of art and culture. It is the mental space between the internal world and external reality and it is thus both subjective and objective. Being human is being in between and thus being able to elaborate with facts, especially when confronted with unexpected negative facts such as a cancer disease.(p. 18)

2. Methodology

2.1. Target Group and Selection

2.2. Primary Data Collection

2.3. Secondary Data

2.4. Measure

2.5. Data Analysis Methods

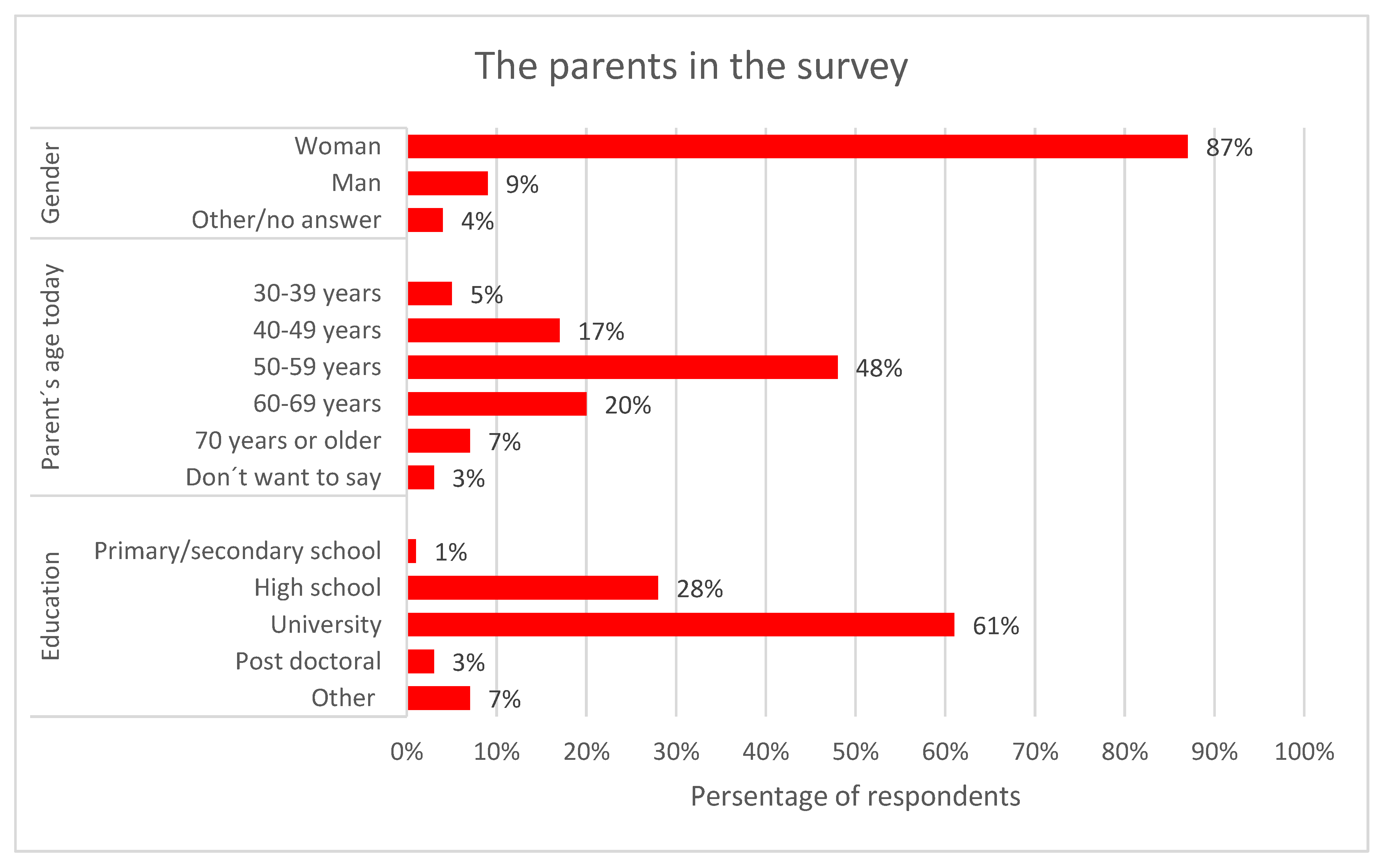

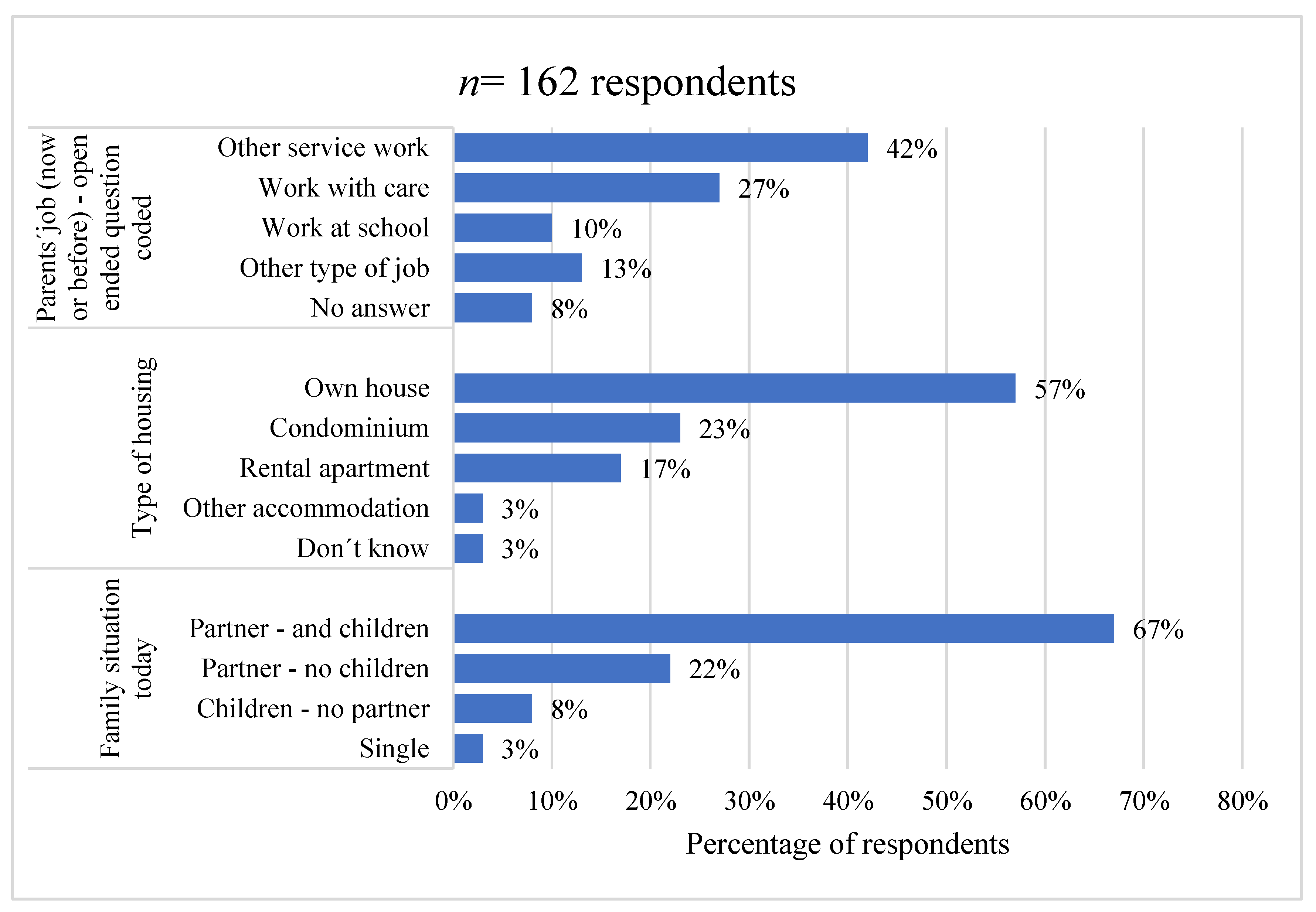

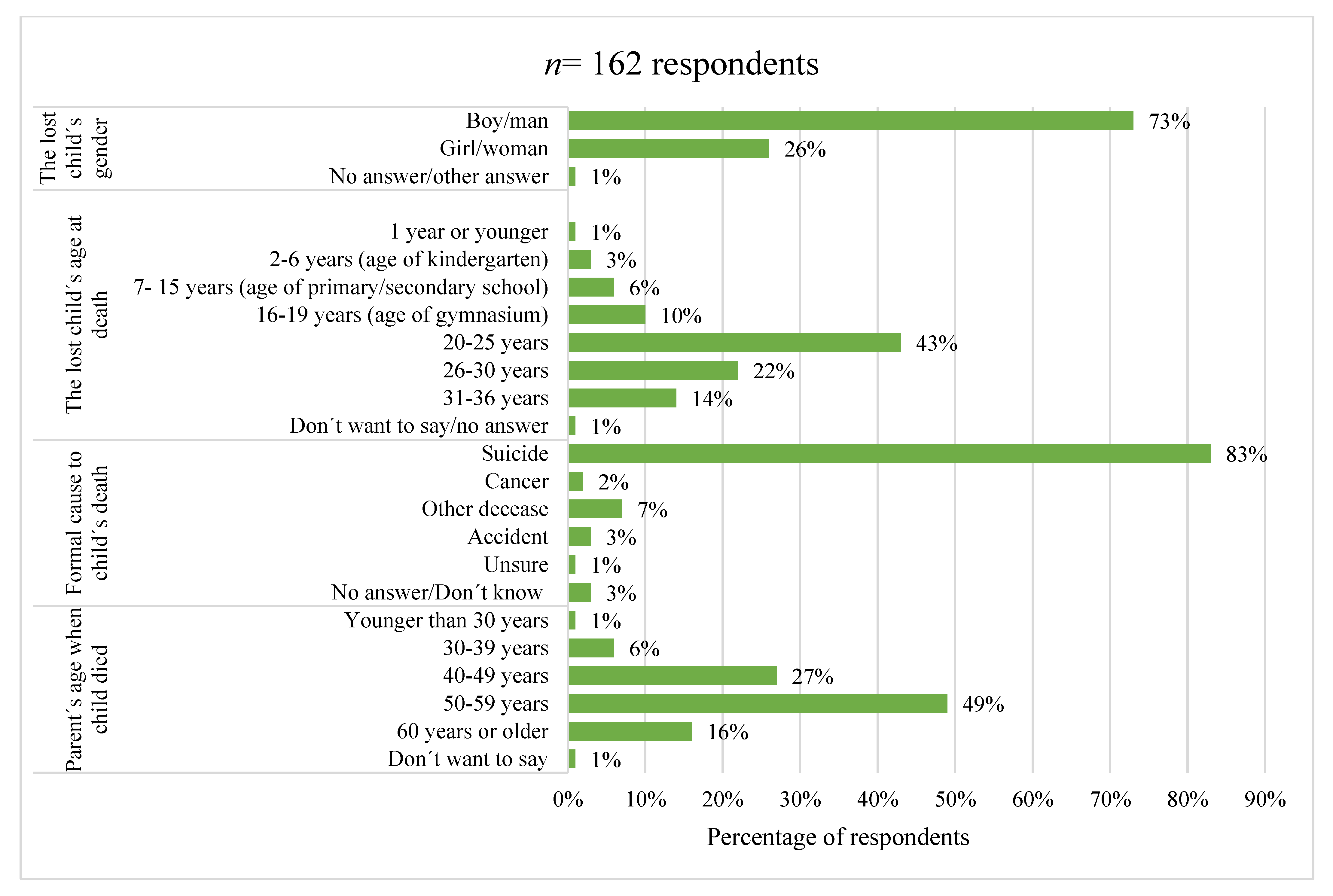

2.6. Description of the Respondents

2.7. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

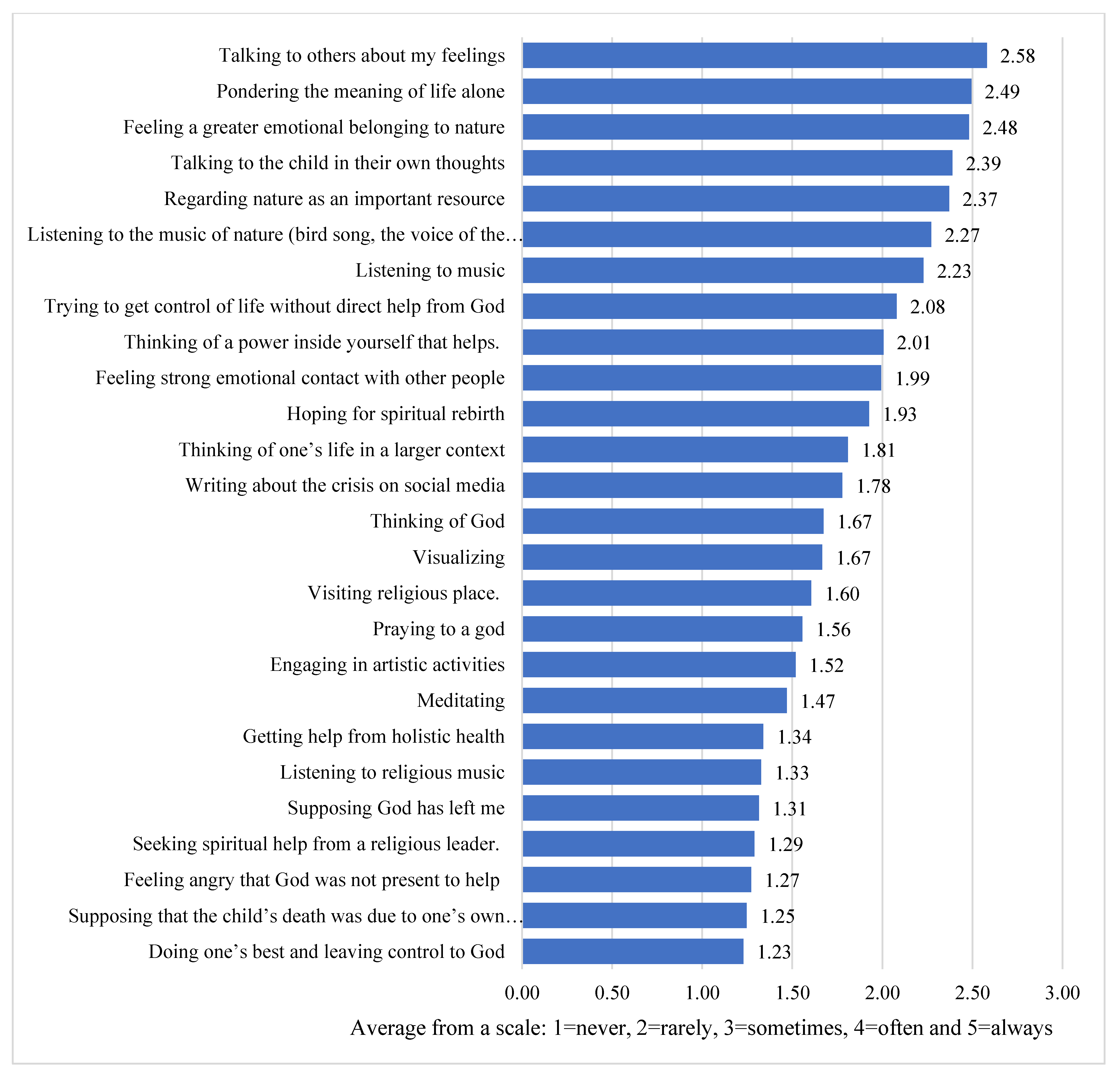

3.1. The Most Common Coping Methods

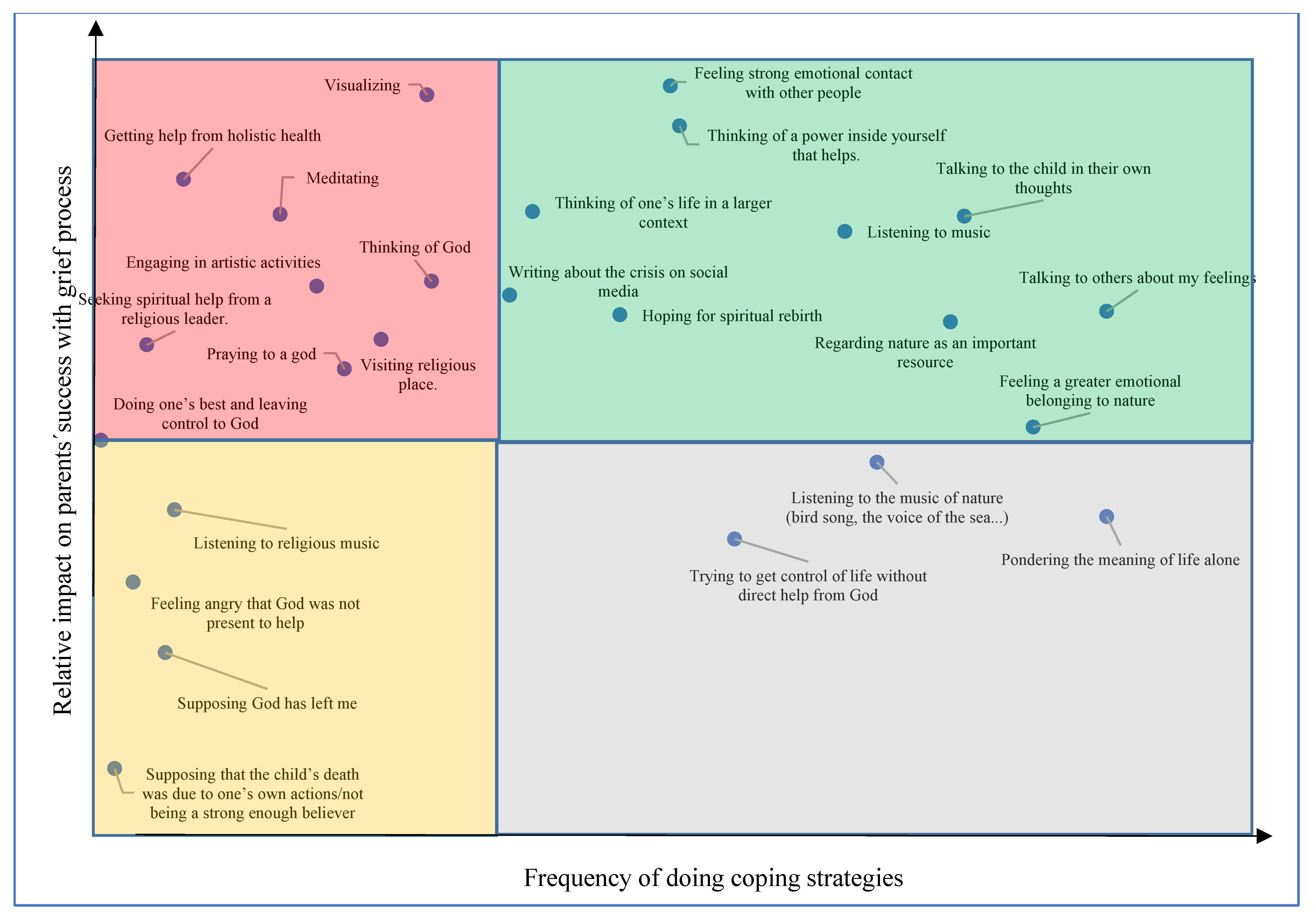

3.2. Effective Coping

4. Discussion

4.1. Cultural Perspective

The question of how religion helps bereaved parents and to what degree religion helps bereaved parents cope with their loss are still scarcely explored. Despite the discussion of the positive roles of being religious in bereavement, there are also debates that claim religious faith may cause negative impacts on bereaved parents.(p. 2)

Religious activities such as prayers, donations, or performing the Hajj (an annual pilgrimage to Mecca) for the deceased child were described as a “bridge” that signified the remembrance of the deceased child. In addition, the bereaved parents believed that religion taught them that even after death, they were still able to give reward to their deceased child.

4.2. Comparison

- The general pattern found in Coping Grief was the same as that found in both Coping Cancer and Coping COVID: the most frequently used coping methods were secular existential coping methods and the least frequently used ones were religious/spiritual methods.

- In Coping Cancer, praying was the 13th method in the ranking of the 24 methods. In Coping Grief, it was ranked lower, at 17 of 26. In Coping COVID, praying was the seventh method out of 15 methods. In all three studies, praying was not among the most frequently used methods, but the different places they occupied in ranking was interesting. In Coping Grief, praying was ranked lower than that in Coping Cancer. The reason may have been that cancer patients believed praying could help change the situation, i.e., being cured, while in case of bereaved parents, changing the situation was impossible as the child was already dead. The partially higher share of praying in Coping COVID, compared to the other two studies, may have been due to the unknown nature of the virus and the unprecedented situation caused by COVID-19, directing some people to ask for help from the realm of the divine.

- Although the three studies showed that connection with others played the role of a coping method, in Coping Grief, this method was used by more respondents. This maybe because, for bereaved parents, confabulating with and confiding in others were mainly for emotional discharge, memorialization, and remembrance; for trying to express negative emotions; and also to keep the memory of the lost child alive [40,41]. In contrast, in Coping Cancer and Coping COVID, the respondents were more inclined to want to forget the crisis.

- All the three studies showed that nature was an important coping method. However, in Coping Cancer and Coping COVID, more participants used this method than in Coping Grief, perhaps because illness and health are more related to nature.

5. Conclusions

5.1. Limitations

5.2. Practical Implications and Policy Recommendations

- Better knowledge of various coping methods involving meaning-making may help social work and psychological care efforts to better help bereaved families manage the effects of loss and grief.

- In countries where religion is integral to people’s lives, planners should pay considerable attention to religious/spiritual coping methods. However, as well as facilitating religious coping methods for those experiencing psychological distress stemming from crises such as loss of a child, these planners should also allot funds and facilities for promoting existential coping methods.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, J.; Precht, D.H.; Mortensen, P.B.; Olsen, J. Mortality in parents after death of a child in Denmark: A nationwide follow-up study. Lancet 2003, 361, 363–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, A.R.; Baker, K.S.; Syrjala, K.; Wolfe, J. Systematic review of psychosocial morbidities among bereaved parents of children with cancer. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2012, 58, 503–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Arnold, J.; Gemma, P.B. The Continuing Process of Parental Grief. Death Study 2008, 32, 658–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shankar, S.; Nolte, L.; Trickey, D. Continuing bonds with the living: Bereaved parents’ narratives of their emotional relationship with their children. Bereave. Care 2017, 36, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stevenson, M.; Achille, M.; Liben, S.; Proulx, M.-C.; Humbert, N.; Petti, A.; Macdonald, M.E.; Cohen, S.R. Understanding How Bereaved Parents Cope With Their Grief to Inform the Services Provided to Them. Qual. Health Res. 2017, 27, 649–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neimeyer, R.A.; Klass, D.; Dennis, M.R. A Social Constructionist Account of Grief: Loss and the Narration of Meaning. Death Study 2014, 38, 485–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neimeyer, R. Narrative Strategies in Grief Therapy. J. Constr. Psychol. 1999, 12, 65–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stroebe, M.; Schut, H. The Dual Process Model of Coping with Bereavement: Rationale and Description. Death Study 1999, 23, 197–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, D.R.; Segerstad, Y.H.A.; Kasperowski, D.; Sandvik, K. Bereaved Parents’ Online Grief Communities: De-Tabooing Practices or Relation-Building Grief-Ghettos? J. Broadcast. Electron. Media 2017, 61, 58–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albuquerque, S.; Buyukcan-Tetik, A.; Stroebe, M.S.; Schut, H.A.W.; Narciso, I.; Pereira, M.; Finkenauer, C. Meaning and coping orientation of bereaved parents: Individual and dyadic processes. PloS ONE 2017, 12, e0178861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Anderson, M.J.; Marwit, S.J.; Vandenberg, B.; Chibnall, J.T. Psychological and Religious Coping Strategies of Mothers Bereaved by the Sudden Death of a Child. Death Study 2005, 29, 811–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, F. Culture, Religion and Spirituality in Coping: The Example of Cancer Patients in Sweden; Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis: Uppsala, Sweden, 2006; p. 53. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmadi, F. Coping with Cancer in Sweden: A Search for Meaning; Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis, Studia Sociologica Upsaliensia: Uppsala, Sweden, 2015; p. 63. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmadi, F.; Ahmadi, N. Existential Meaning-Making for Coping with Serious Illness: Studies in Secular and Religious Societies; Routledge: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmadi, F.; Matos, P.M.; Tavares, R.; Tomás, C.; Ahmadi, N. Religious/Spiritual Coping Methods among Cancer Patients in Portugal. Illness Crisis Loss 2021, 29, 301–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, F.; Rabbani, M. Religious Coping Methods among Cancer Patients in Three Islamic Countries: A Comparative Perspective. Int. J. Soc. Sci. Stud. 2019, 7, 72–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ahmadi, F.; Hussin, N.A.M.; Mohammad, T. Religion, Culture and Meaning-Making Coping: A Study among Cancer Patients in Malaysia. J. Relig. Health 2018, 58, 1909–1924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ahmadi, F.; Erbil, P.; Ahmadi, N.; Önver, A.C. Religion, Culture and Meaning-Making Coping: A Study among Cancer Patients in Turkey. J. Relig. Health 2018, 58, 1115–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ahmadi, F.; Khodayarifard, M.; Zandi, S.; Khorrami-Markani, A.; Ghobari-Bonab, B.; Sabzevari, M.; Ahmadi, N. Religion, culture and illness: A sociological study on religious coping in Iran. Ment. Health Relig. Cult. 2018, 21, 721–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ahmadi, F.; Önver, A.C.; Erbil, P.; Ortak, A.; Ahmadi, N. A Survey Study among Cancer Patients in Turkey: Meaning-Making Coping. Illness Crisis Loss 2020, 28, 234–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, F.; Park, J.; Kim, K.M.; Ahmadi, N. Meaning-Making Coping among Cancer Patients in Sweden and South Korea: A Comparative Perspective. J. Relig. Health 2017, 56, 1794–1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ahmadi, N.; Ahmadi, F. The Use of Religious Coping Methods in a Secular Society. Illness Crisis Loss 2017, 25, 171–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ahmadi, F.; Park, J.; Kim, K.M.; Ahmadi, N. Exploring Existential Coping Resources: The Perspective of Koreans with Cancer. J. Relig. Health 2016, 55, 2053–2068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ahmadi, F.; Önver, A.C.; Akhavan, S.; Zandi, S. Meaning-Making Coping With COVID-19 in Academic Settings: The Case of Sweden. Illness Crisis Loss 2021, 10541373211022002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, F.; Ahmadi, N. Nature as the Most Important Coping Strategy among Cancer Patients: A Swedish Survey. J. Relig. Health 2015, 54, 1177–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ganzevoort, R.R. Religious Coping Reconsidered, Part Two: A Narrative Reformulation. J. Psychol. Theol. 1998, 26, 276–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pargament, K.I. The Psychology of Religion and Coping; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus, S.R.; Folkman, S. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- la Cour, P.; Hvidt, N.C. Research on meaning-making and health in secular society: Secular, spiritual and religious existential orientations. Soc. Sci. Med. 2010, 71, 1292–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Folsterling, F. Attribution: An Introduction to Theory, Research and Application; Psychology Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Salander, P. Introduction: A critical discussion on the concept of spirituality in research on health. In Coping with Cancer in Sweden: A Search for Meaning; Ahmadi, F., Ed.; Uppsala University: Uppsala, Stockholm, Sweden, 2015; pp. 13–27. [Google Scholar]

- Pargament, K.I.; Koenig, H.G.; Perez, L.M. The many methods of religious coping: Development and initial validation of the RCOPE. J. Clin. Psychol. 2000, 56, 519–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, M.P. Parental Bereavement and Religious Factors. Omega-J. Death Dying 2002, 45, 187–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, K.; King, M.; Jones, L.; Tookman, A.; Blizard, R. Spiritual beliefs may affect outcome of bereavement: Prospective study. BMJ 2002, 324, 1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Halifax, J. Being with Dying: Cultivating Compassion and Fearlessness in the Presence of Death; Shambhala: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed Hussin, N.A.; Guàrdia-Olmos, J.; Aho, A.L. The use of religion in coping with grief among bereaved Malay Muslim parents. Ment. Health Relig. Cult. 2018, 21, 395–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kara, E. A Qualitative Research on University Students’ Religious Approaches during the Grieving Process. Spirit. Psychol. Couns. 2017, 2, 203–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- World Value Survey (2010–2014). World Values Survey Data Analysis Tool. Available online: https://www.worldvaluessurvey.org/WVSOnline.jsp (accessed on 5 January 2021).

- Hagevi, M. Beyond Church and State: Private Religiosity and Post-Materialist Political Opinion among Individuals in Sweden. J. Church State 2012, 54, 499–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffert, S.D. “A Very Peculiar Sorrow”: Attitudes Toward Infant Death in the Urban Northeast, 1800–1860. Am. Q. 1987, 39, 601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Znoj, H.J.; Keller, D. Mourning Parents: Considering Safeguards and Their Relation to Health. Death Study 2002, 26, 545–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenblatt, P.C. Cultural competence and humility. In Handbook of Social Justice in Loss and Grief: Exploring Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion; Harris, D.L., Bordere, T.C., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Riches, G.; Dawson, P. Communities of feeling: The culture of bereaved parents. Mortality 1996, 1, 143–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Present Study | Swedish Population 2019 (SCB) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Women | 87% | 49% |

| Men | 9% | 51% | |

| Other/no answer | 4% | - | |

| Age groups (share of interval 30+ years) | 30–39 years | 5% | 22% |

| 40–49 years | 17% | 20% | |

| 50–59 years | 48% | 20% | |

| 60–69 years | 20% | 17% | |

| 70 years or older | 7% | 21% | |

| Unknown | 3% | - | |

| Education | Elementary school | 1% | 11% |

| High school | 28% | 43% | |

| University | 61% | 46% | |

| Other | 7% | - |

| Secular Existential Methods | Religious/Spiritual Methods |

|---|---|

| 1. Talking to others about my feelings 2. Pondering on the meaning of life alone 3. Walking in nature and feeling great emotional belonging to nature 4. Talking to the child in their own thoughts 5. Regarding nature as an important resource 6. Listening to the music of nature (bird song, voice of the sea, etc.) 7. Listening to music 8. Trying to get control of life without direct help from God 9. Thinking of a power inside yourself that helps 10. Feeling strong emotional contact with other people 12. Thinking of one’s life in a larger context 13. Writing about the crisis on social media 15. Visualizing 18. Engaging in artistic activities 19. Meditating 20. Getting help from holistic health | 11. Hoping for spiritual rebirth 14. Thinking of God 16. Visiting the religious places 17. Praying to a god 21. Listening to religious music 22. Supposing God has left them 23. Seeking spiritual help from a religious leader 24. Feeling angry that God was not present to help 25. Supposing that losing of one’s child was because of one’s actions/not being a strong enough believer 26. Doing one’s best and leaving control to God |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ahmadi, F.; Zandi, S. Meaning-Making Coping Methods among Bereaved Parents: A Pilot Survey Study in Sweden. Behav. Sci. 2021, 11, 131. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs11100131

Ahmadi F, Zandi S. Meaning-Making Coping Methods among Bereaved Parents: A Pilot Survey Study in Sweden. Behavioral Sciences. 2021; 11(10):131. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs11100131

Chicago/Turabian StyleAhmadi, Fereshteh, and Saeid Zandi. 2021. "Meaning-Making Coping Methods among Bereaved Parents: A Pilot Survey Study in Sweden" Behavioral Sciences 11, no. 10: 131. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs11100131

APA StyleAhmadi, F., & Zandi, S. (2021). Meaning-Making Coping Methods among Bereaved Parents: A Pilot Survey Study in Sweden. Behavioral Sciences, 11(10), 131. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs11100131